Many things are possible. Few things are certain.

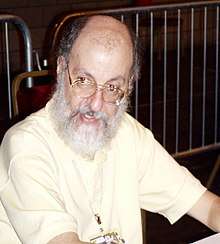

Harry Norman Turtledove (born 14 June 1949) is an American novelist, best known for his works in several genres, including that of alternate history, historical fiction, fantasy, and science fiction.

Fiction has to be plausible. All history has to do is happen.

Bureau of Ordnance, Richmond

January 17, 1864

General Lee:

I have the honor to present to you with this letter Mr. Andries Rhoodie of Rivington, North Carolina, who has demonstrated in my presence a new rifle, which I believe may prove to be of the most significant benefit conceivable to our soldiers. As he expressed the desire of making your acquaintance & as the Army of Northern Virginia will again, it is likely, face hard fighting in the months ahead, I send him on to you that you may judge both him & his remarkable weapon for yourself. I remain,

Your most ob't servant,

Josiah Gorgas

Colonel

January 17, 1864

General Lee:

I have the honor to present to you with this letter Mr. Andries Rhoodie of Rivington, North Carolina, who has demonstrated in my presence a new rifle, which I believe may prove to be of the most significant benefit conceivable to our soldiers. As he expressed the desire of making your acquaintance & as the Army of Northern Virginia will again, it is likely, face hard fighting in the months ahead, I send him on to you that you may judge both him & his remarkable weapon for yourself. I remain,

Your most ob't servant,

Josiah Gorgas

Colonel

"Mighty generous of you," Lincoln said with cutting irony. "And one fine day, I reckon, we'll have friends in Europe, too, friends who'll help us get back what's rightfully ours and what you've taken away." "A European power- to help you against England and France?" For the first time, Lord Lyons was undiplomatic enough to laugh. American bluster was bad enough most times, but this lunacy- "Good luck to you, Mr. President. Good luck."

.svg.png)

"I'm Jake Featherston, and I'm here to tell you the truth."

June 21 passed through to June 22. All that coffee made Jake's heart thud and soured his stomach. He gulped a Bromo-Seltzer and went on. At a quarter past three, the drone of airplane engines and the thunder of distant artillery- not distant enough; damn those Yankee robbers!- made him whoop for sheer glee. He'd waited so long. Now his day was here.

"No epilogue here, unless you make it;

If you want your freedom, go and take it."

If you want your freedom, go and take it."

A great roar, a roar full of triumph, rose from the men in front of him as they passed the crest of the hill and swept on towards the Tower Ditch and the walls beyond. And when Shakespeare crested the hill himself, he looked ahead and roared too, in joy and amazement and suddenly flaring hope. Will Kemp had been right, right and more than right. All the gates to the Tower of London stood open.

"Think you're the only mother's son born a fool in England?"

Quotes

- Fiction has to be plausible. All history has to do is happen.

- Many things are possible. Few things are certain.

- I see people who write characters who are loonies and make them convincing and believable, and I envy them tremendously. I don’t really understand them. It’s funny, because I’ve created my own monster. In the ‘Great War’ and ‘American Empire’ books, I’m writing the person who is the functional equivalent of Adolf Hitler. I’m inside his head — and that’s a very strange place for somebody who thinks of himself as a fairly rational fellow to be. That’s alarming

- I suspect S.F. has an individualistic, antiauthoritarian trend to it not least because so many of the people who read and write it (not all by any means, but quite a few) are innerdirected introverts who make neither good leaders nor good followers. Am I talking about myself? Well, now that you mention it, yes. But I ain’t the only one, not even close.

The Guns of the South (1992)

- Robert E. Lee paused to dip his pen once more in the inkwell. Despite flannel shirt, uniform coat, and heavy winter boots, he shivered a little. The headquarters tent was cold. The winter had been harsh, and showed no signs of growing any milder. New England weather, he thought, and wondered why God had chosen to visit it upon his Virginia.

- p. 3

- Keeping the Army of Northern Virginia fed and clothed was a never-ending struggle. His men were making their own shoes now, when they could get the leather, which as not often. The ration was down to three-quarters of a pound of meat a day, along with a little salt, sugar, coffee- or rather, chicory and burnt grain- and lard. Bread, rice, corn... they trickled up the Virginia Central and Orange and Alexandria Railroad every so often, but not nearly often enough. He would have to cut the daily allowance again, if more did not arrive soon. President Davis, however, was as aware of all that as Lee could make him. To hash it over once more would only seem like carping.

- p. 4

- A gun cracked, quite close to the tent. Soldier's instinct pulled Lee's head up. Then he smiled and laughed to himself. One of his staff officers, most likely, shooting at a possum or squirrel. He hoped the young man had scored a hit. But no sooner had the smile appeared than it vanished. The report of the gun sounded- odd. It had been an abrupt bark, not a pistol shot or the deeper boom of an Enfield rifle musket. Maybe it was a captured Federal weapon. The gun cracked again and again and again. Each report came closer to the one than two heartbeats were to each other. A Federal weapon indeed, Lee thought: one of those fancy repeaters their cavalry like so well. The fusillade went on and on. He frowned at the waste of precious cartridges- no Southern armory could easily duplicate them. He frowned once more, this time in puzzlement, when silence fell. He had automatically kept track of the number of rounds fired. No Northern rifle he knew was a thirty-shooter. He turned his mind back to the letter to President Davis. -Valley, he wrote. Then gunfire rang out again, an unbelievably rapid stutter of shots, altogether too quick to count and altogether unlike anything he had ever heard. He took off his glasses and set down the pen. Then he put on a hat and got up to see what was going on.

- p. 4

- Bureau of Ordnance, Richmond

January 17, 1864

General Lee:

I have the honor to present to you with this letter Mr. Andries Rhoodie of Rivington, North Carolina, who has demonstrated in my presence a new rifle, which I believe may prove to be of the most significant benefit conceivable to our soldiers. As he expressed the desire of making your acquaintance & as the Army of Northern Virginia will again, it is likely, face hard fighting in the months ahead, I send him on to you that you may judge both him & his remarkable weapon for yourself. I remain,

Your most ob't servant,

Josiah Gorgas

Colonel- p. 5

- Walter Taylor asked, "Mr. Rhoodie, what do you call this rifle of yours? Is it a Rhoodie, too? Most inventors name their products for themselves, do they not?" "No, it's not a Rhoodie." The big stranger unslung the rifle, held it in both hands as gently as if it were a baby. "Give it its proper name, Major. It's an AK-47."

- p. 13

- Lang kept at it until everyone had had a turn shooting an AK-47. Then he said, "This weapon can do one other thing I haven't shown you yet. When you move the change lever all the way down instead of to the middle position, this is what happens." He stuck a fresh clip in the repeater, turned toward the target circle, and blasted away. He went through the whole magazine almost before Caudell could draw in a startled breath. "Good God almighty," Rufus Daniel said, peering in awe at the brass cartridge cases scattered around Lang's feet. "Why didn't he show us that in the first place?" He was not the only one to raise the question; quite a few shouted it. Caudell kept quiet. By now, he was willing to assume Lang knew what he was doing. The weapons instructor stayed perfectly possessed. He said, "I didn't show you that earlier because it wastes ammunition and because the weapon accurate past a few meters- yards- on full automatic. You can only carry so many rounds. If you shoot them all off in the first five minutes of battle, what will you do once they're gone? Think hard on that, gentlemen, and drill it into your private soldiers. This weapon requires fire discipline- requires it, I say again."

- p. 31

- "It is an evil, sir, an unmitigated evil," Lincoln said. "I shall never forget the group of chained Negroes I saw going down the river to be sold close to a quarter of a century ago. Never was there so much misery, all in one place. If your secession triumphs, the South will be a pariah among nations." "We shall be recognized as what we are, a nation among nations," Lee returned. "And, let me repeat, my being here is a sign secession has triumphed. What I would seek to do now, subject to the ratification of my superiors, is suggest terms to halt the war between the United States and Confederate States." Lincoln refused to call Lee's country by its proper name. As a small measure of revenge, Lee put extra weight on that name. Lincoln sighed. This was the moment he had tried to evade, but there was no evading it, not with the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia in his parlor. "Name your terms, General," he said in a voice full of ashes.

- p. 176-177

- The crowd of ragged Confederates on the White House lawn had doubled and more since he went in to confer with Lincoln. The trees were full of men who had climbed up so they could see over their comrades. Off in the distance, cannon occasionally still thundered; rifles popped like firecrackers. Lee quietly said to Lincoln, "Will you send out your sentries under flag of truce to bring word of the armistice to those Federal positions still firing upon my men?" "I'll see to it," Lincoln promised. He pointed to the soldiers in gray, who had quieted expectantly when Lee came out. "Looks like you've given me sentries enough, even if their coats are the wrong color." Few men could have joked so with their cause in ruins around them. Respecting the Federal President for his composure, Lee raised his voice: "Soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia, after three years of arduous service, we have achieved that for which we took up arms-" He got no further. With one voice, the men before him screamed out their joy and relief. The unending waves of noise beat at him like a surf from a stormy sea. Battered forage caps and slouch hats flew through the air. Soldiers jumped up and down, pounded on one another's shoulders, danced in clumsy rings, kissed each other's bearded, filthy faces. Lee felt his own eyes grow moist. At last the magnitude of what he had won began to sink in.

- p. 180

- "With these victories to which you refer, the Confederate States do seem to have retrieved their falling fortunes," Lord Lyons said. "I have no reason to doubt that Her Majesty's government will soon recognize that fact." "Thank you, your excellency," Lee said quietly. Even had Lincoln refused to give up the war- not impossible, with the Mississippi valley and many coastal pockets held by virtue of Northern naval power and hence relatively secure from rebel AK-47s- recognition by the greatest empire on earth would have assured Confederate independence. Lord Lyons held up a hand. "Many among our upper classes will be glad enough to welcome you to the family of nations, both as a result of your successful fight for self-government and because you have given a black eye to the often vulgar democracy of the United States. Others, however, will judge your republic a sham, with its freedom for white men based upon Negro slavery, a notion loathsome to the civilized world. I should be less than candid if I failed to number myself among that latter group." "Slavery was not the reason the Southern states chose to leave the Union," Lee said. He was aware he sounded uncomfortable, but went on, "We sought only to enjoy the sovereignty guaranteed us under the constitution, a right the North wrongly denied us. Our watchword all along has been, we wish but to be left alone."

- p. 182-183

- "And what sort of country shall you build upon that watchword, General?" Lord Lyons asked. "You cannot be left entirely alone; you are become, as I said, a member of the family of nations. Further, this war has been hard on you. Much of your land has been ravaged or overrun, and in those places where the Federal army has been, slavery lies dying. Shall you restore it there at the point of a bayonet? Gladstone said October before last, perhaps a bit prematurely, that your Jefferson Davis had made an army, the beginnings of a navy, and, more important than either, a nation. You Southerners may have made the Confederacy into a nation, General Lee, but what sort of nation shall it be?" Lee did not answer for most of a minute. This pudgy little man in his comfortable chair had put into a nutshell his own worries and fears. He'd had scant time to dwell on them, not with the war always uppermost in his thoughts. But the war had not invalidated any of the British minister's questions- some of which Lincoln had also asked- only put off the time at which they would have to be answered. Now that time drew near. Now that the Confederacy was a nation, what sort of nation would it be? At last he said, "Your excellency, at this precise instant I cannot fully answer you, save to say that, whatever sort of nation we become, it shall be one of our own choosing." It was a good answer. Lord Lyons nodded, as if in thoughtful approval. Then Lee remembered the Rivington men. They too had their ideas on what the Confederate States of America should become.

- p. 183

- The Federal commissioners sat down across the mahogany table from their Southern hosts. After a couple of minutes of chitchat meant to be polite- but during which the three Confederates managed to avoid speaking directly to Butler- Seward said, "Gentlemen, shall we attempt to repair the unpleasantness that lies between our two governments?" "Had you acknowledged from the outset that this land contained to governments, sir, all the unpleasantness, as you call it, would have been avoided," Alexander Stephens pointed out. Like his body, his voice was light and thin. "That may be true, but it's moot now," Stanton said. "Let's deal with the situation as we have it, shall we? Otherwise useless recriminations will take up all our time and lead us nowhere. It was, if I may say so, useless recriminations on both sides that led to the breach between North and South."

- p. 226

- Judah Benjamin said, "The nations of Europe continue to abhor our policy, try as we will to convince them that we cannot do otherwise. Mr. Mason has written from London that Her Majesty's government might well have been willing to extend us recognition two years ago, were it not for the continuation of slavery among us: so Lord Russell has assured him, at any rate. Mr. Thouvenel, the French foreign minister, has expressed similar sentiments to Mr. Slidell in Paris." Slavery, Lee thought. In the end, the world's outside view of the Confederate States of America was colored almost exclusively by its response to the South's peculiar institution. Never mind that the U.S. Constitution was a revocable compact between independent states, never mind that the North had consistently used its numerical majority to force through Congress tariffs that worked only to ruin the South. So long as black men were bought and sold, all the high ideals of the Confederacy would be ignored.

- p. 234

- President Davis said, "The 'free' factory worker in Manchester or Paris- yes, in Boston as well- is free only to starve. As Mr. Hammond from South Carolina put it so pungently in the chambers of the U.S. Senate a few years ago, every society rests upon a mudsill of brute labor, from which the edifice of civilization arises. We are but more open and honest about the nature of our mudsill than other nations, which gladly exploit a worker's labor but, when he can no longer provide it, cast him aside like a used sheet of foolscap."

- p. 234

- Lee wondered how Jefferson Davis had ever managed to inveigle him into accepting the Confederate Presidency. Even without counting the armed guards who surrounded the presidential residence on Shockoe Hill, he found himself a prisoner of his position. To do everything that needed doing, he should have been born triplets. The one of him available was not nearly enough; whenever he did anything, he felt guilty because he was neglecting something else.

- p. 458

- "But there is no such thing as possessing a little freedom," Lee mused. "Once one enjoys any whatsoever, he will seek it all."

- p. 512

The Great War: American Front (1998)

- "I do thank Lord Palmerston for his good offices," he said, "but, as we deny there is any such thing as the government of the Confederate States, Earl Russell can't very well mediate between them and us." Lord Lyons sighed. "You say this, Mr. President, with the Army of Northern Virginia encamped in Philadelphia?" "I would say it, sir, if that Army were encamped on the front lawn of the White House," Lincoln replied.

- p. 6

- "Let's dicker, Lord Lyons," Lincoln said; the British minister needed a moment to understand he meant bargain. Lincoln gave him that moment, reaching into a desk drawer and drawing out a folded sheet of paper that he set on top of the desk. "I have here, sir, a proclamation declaring all Negroes held in bondage in those areas now in rebellion against the lawful government of the United States to be freed as of next January first. I had been saving this proclamation against a Union victory, but circumstances being as they are-" Lord Lyons spread his hands with genuine regret. "Had you won such a victory, Mr. President, I should not be visiting you today with the melancholy message I bear from my government. You know, sir, that I personally despise the institution of chattel slavery and everything associated with it." He waited for Lincoln to nod before continuing. "That said, however, I must tell you that an emancipation proclamation issued after the series of defeats Federal forces have suffered would be perceived as a cri de coeur, a call for servile insurrection to aid your flagging cause, and as such would not be favorably received in either London or Paris, to say nothing of its probable effect in Richmond. I am sorry, Mr. President, but this is not the way out of your dilemma." Lincoln unfolded the paper on which he'd written the decree abolishing slavery in the seceding states, put on a pair of spectacles to read it, sighed, folded it again, and returned it to its drawer without offering to show it to Lord Lyons. "If that doesn't help us, sir, I don't know what will," he said. His long, narrow face twisted, as if he were in physical pain. "Of course, what you're telling me is that nothing helps us, nothing at all."

- p. 7

- "The ability to see what is, sir, is essential for the leader of a great nation," the British minister said. He wanted to let Lincoln down easy if he could. "I see what is, all right. I surely do," the president said. "I see that you European powers are taking advantage of this rebellion to meddle in America, the way you used to before the Monroe Doctrine warned you to keep your hands off. Napoleon props up a tin-pot emperor in Mexico, and now France and England are in cahoots"- another phrase that briefly baffled Lord Lyons- "to help the Rebels and pull us down. All right, sir." He breathed heavily. "If that's the way the game's going to be played, we aren't strong enough to prevent it now. But I warn you, Mr. Minister, we can play, too." "You are indeed a free and independent nation," Lord Lyons agreed. "You may pursue diplomacy to the full extent of your interests and abilities." "Mighty generous of you," Lincoln said with cutting irony. "And one fine day, I reckon, we'll have friends in Europe, too, friends who'll help us get back what's rightfully ours and what you've taken away." "A European power- to help you against England and France?" For the first time, Lord Lyons was undiplomatic enough to laugh. American bluster was bad enough most times, but this lunacy- "Good luck to you, Mr. President. Good luck."

- p. 9

- A fellow with a great voice shouted, "Hearken now to the words of the President of the Confederate States of America, the honorable Woodrow Wilson." The president turned this way and that, surveying the great swarm of people all around him in the moment of silence the volley had brought. Then, swinging back to face the statue of George Washington- and, incidentally, Reginald Bartlett- he said, "The father of our country warned us against entangling alliances, a warning that served us well when we were yoked to the North, before its arrogance created in our Confederacy what had never existed before- a national consciousness. That was our salvation and our birth as a free and independent country." Silence broke then, with a thunderous outpouring of applause. Wilson raised a bony right hand. Slowly, silence, of a semblance of it, returned. The president went on, "But our birth of national consciousness made the United States jealous, and they tried to beat us down. We found loyal friends in England and France. Can we now stand aside when the German tyrant threatens to grind them under his iron heel?" "No!" Bartlett shouted himself hoarse, along with thousands of his countrymen. Stunned, deafened, he had trouble hearing what Wilson said next: "Jealous still, the United States in their turn also developed a national consciousness, a dark and bitter one, as any so opposed to ours must be." He spoke not like a politician inflaming a crowd but like a professor setting out arguments- he had taken one path before choosing the other. "The German spirit of arrogance and militarism has taken hold in the United States; they see only the gun as the proper arbiter between nations, and their president takes Wilhelm as his model. He struts and swaggers and acts the fool in all regards." Now he sounded like a politician; he despised Theodore Roosevelt, and took pleasure in Roosevelt's dislike for him.

- p. 32

- "And now, as a result of honoring our commitment to our gallant allies, that man Roosevelt has sought from the U.S. Congress a declaration of war not only against England and France but also against the Confederate States of America. His servile lackeys, misnamed Democrats, have given him what he wanted, and the telegraph informs me that fighting has begun along our border and on the high seas. Leading our great and peaceful people into war is a fearful thing, not least because, with the great advances of science and industry over the past half-century, this may prove the most disastrous and terrible of all wars, truly a war of the nations: indeed a war of the world. But right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for those things we have always held dear in our hearts: for the rights of the Confederate States and of the white men who live in them; for the liberties of small nations everywhere from outside oppression; for our own freedom and independence from the vicious, bloody regime to the north. To such a task we can dedicate our lives and fortunes, everything we are and all that we have, with the pride of those who know the day has come when the Confederacy is privileged to spend her blood and her strength for the principles that gave her birth and led to her present happiness. God helping us, we can do nothing else. Men of the Confederacy, is it your will that a state of war should exist henceforth between us and the United States of America?" "Yes!" The answer roared from Reginald Bartlett's throat, as from those of the other tens of thousands of people jamming the Capitol Square. Someone flung a straw hat in the air. In an instant, hundreds of them, Bartlett's included, were flying. A great chorus of "Dixie" rang out, loud enough, Bartlett thought, for the damnyankees to hear it in Washington.

- p. 33

- Someone tapped him on the shoulder. he whirled around- and stared into the angry face of Milo Axelrod, his boss. "I told you to stay and mind the shop, dammit!" the druggist roared. "You're fired!" Bartlett snapped his fingers under the older man's nose. "And this here is how much I care," he said. "You can't fire me, on account of I damn well quit. They haven't called up my regiment yet, but I'm joining the Army now, is what I'm doing. Go peddle your pills- us real men will save the country for you. A couple of months from now, after we've licked the Yankees, you can tell me you're sorry."

- p. 33

- Some time in the middle of the night, somebody gently shook him awake. He looked up to find Perseus squatting beside his bedroll. In a voice not much above a whisper, the laborer said, "We ain't actin' like niggers no more, Marse Jake. Figured I'd tell you, on account of you know we don't got to. You want to be careful fo' a while, is all I got to say." He slipped away. Featherston looked around, not altogether sure he hadn't been dreaming. He didn't see Perseus. He didn't hear anything. He rolled over and went back to sleep. A little before dawn, Captain Stuart's angry voice woke him: "Pompey? Where the hell are you, Pompey? I call you, you bring your black ass over here and find out what I want, do you hear me? Pompey!" Stuart's shouts went on and on. Wherever Pompey was, he wasn't coming when called. And then Michael Scott hurried up to Jake, a worried look on his face. "Sarge, you seen Nero or Perseus? Don't know where they're at, but they sure as hell ain't where they're supposed to be." "Jesus," Featherston said, bouncing to his feet. "It wasn't a dream. Sure as hell it wasn't." Scott stared at him, having no idea what he meant. He wasn't altogether sure himself. One thing seemed clear: trouble was brewing.

- p. 492

- Scipio stared in through the window at the growing fire, feeling a pang for beauty destroyed no matter upon how much suffering it rested. The bourgeois in you, Cassius would have said. "You got to do dat, Cass?" he asked. "Got to," Cassius said firmly. "Gwine burn it all, Kip. De revolution here."

- p. 503

The Great War: Walk in Hell (1999)

The Great War: Breakthroughs (2000)

Ruled Britannia (2002)

- Dying Boudicca managed a feeble nod, and sent her last words out to a breathlessly silent Theatre:

"E'en so; 'Tis true. Oh!- I feel the poison!

We Britons never did, nor never shall,

Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror,

But when we do first help to wound ourselves,

Come the three corners of the world in arms,

And we shall shock them. Naught shall make us rue,

If Britons to themselves do rest but true."

She fell back and lay dead. Shakespeare strode forward, to the very front of the stage. Into more silence, punctuated only by sobs, he said,

"No epilogue here, unless you make it;

If you want your freedom, go and take it."- p. 375

- And then, to Shakespeare's amazement and dismay, Burbage and Will Kemp tramped forward together, both of them plainly intent on marching on the Tower of London, too. Shakespeare seized Burbage's arm. "Hold, Dick!" he said urgently. "Let not this wild madness infect your wit. Can a swarm of rude mechanicals pull down those gray stone walls? The soldiers on 'em'll work a fearful slaughter. Throw not your life away." Before Burbage could answer, Will Kemp did: "The soldiery on the walls may work a fearful slaughter, ay, an they have the stomach for't. But think you 'twill be so? A plot that stretcheth to the Theatre surely shall not fall short of the tower."

- p. 376

- But no line of ferocious, lean-faced, swarthy Spaniards appeared. Shouts and cries and the harsh snarl of gunfire suggested the dons were busy, desperately busy, elsewhere in London. When chance swept Shakespeare and Richard Burbage together for a moment, the player said, "Belike they'll make a stand at the tower." "Likely so," Shakespeare agreed unhappily. Those frowning walls had been made to hold back an army, and this... thing he was a part of was anything but. Up Tower Hill, where he'd watched the auto de fe almost a year before. A great roar, a roar full of triumph, rose from the men in front of him as they passed the crest of the hill and swept on towards the Tower Ditch and the walls beyond. And when Shakespeare crested the hill himself, he looked ahead and roared too, in joy and amazement and suddenly flaring hope. Will Kemp had been right, right and more than right. All the gates to the Tower of London stood open.

- p. 379

- Someone bumped into Shakespeare: Will Kemp. The clown made a leg- a cramped leg, in the crush- at him. "Give you good den, gallowsbait," he said cheerfully. "Go to!" Shakespeare said. "Meseems we are well begun here." "Well begun, ay. And belike, soon we shall be well ended, too." Kemp jerked his head to one side, made his eyes bulge, and stuck out his tongue as if newly hanged. With a shudder, Shakespeare said, "If your wind of wit sit in that quarter, why stand you here and not with the Spaniards?" "Why?" Kemp kissed him on the cheek. "Think you're the only mother's son born a fool in England?"

- p. 394

- For the Spanish Armada to have conquered England in 1588 would not have been easy. King Philip's fleet would have needed several pieces of good fortune it did not get: a friendlier wind at Calais, perhaps, one that might have kept the English from launching their fireships against the Armada; and a falling-out between the Dutch and English that could have let the Duke of Parma put to sea from Dunkirk and join his army to the Duke of Medina Sidonia's fleet for the invasion of England. Getting Spanish soldiers across the Channel would have been the hard part. Had it been accomplished, the Spanish infantry, the best in the world at the time and commanded by a most able officer, very probably could have beaten Elizabeth's forces on land.

- Historical Note, p. 457

American Empire: The Victorious Opposition (2003)

- Manicheism, n., The ancient Persian doctrine of an incessant warfare between Good and Evil. When Good gave up the fight the Persians joined the victorious Opposition.

- Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary

- Clarence Potter walked through the streets of Charleston, South Carolina, like a man caught in a city occupied by the enemy. That was exactly how he felt. It was March 5, 1934- a Monday. The day before, Jake Featherston of the Freedom Party had taken the oath of office as President of the Confederate States of America. "I've known that son of a bitch was a son of a bitch longer than anybody," Potter muttered.

- p. 1

- "I'm Jake Featherston, and I'm here to tell you the truth."

- p. 274

- Jake jerked a thumb at the door. "Al right. Get the hell out of here, and take all your pictures of naked women with you." "Yes, sir." Chuckling, Potter scooped up the folder of reconnaissance photos and started out. He paused with his hand on the doorknob. "Good luck," he said. "You've done everything you could to get us ready, but we'll still need it." "I'll put in a fresh requisition with the Quartermaster Corps," Jake said. Potter nodded and left. Jake shook his head in bemusement. He might have made stupid jokes like that with Ferd Koenig and a couple of other old-time Party buddies, but not with anybody else. So why make them with Potter? But he didn't need long to find the answer. He'd known Potter longer than he'd known Koenig or any of the other Party men. They'd both hung tough when the Army of Northern Virginia was falling to pieces all around them. If the president of the greatest country in North America- no, in the world!- couldn't joke around with the one man who'd known him when he was just a sergeant, with whom could he joke? Nobody. Nobody at all.

- p. 533

- Lulu made most of his telephone calls. He made this one himself, on a special line that didn't pass through her desk. It went straight from his office to the War Department. Men checked twice a day to make sure the damnyankees didn't tap it. It rang only once before the Chief of the General Staff picked it up. "Forrest speaking." "Featherston," Jake said, and then, "Blackbeard." He hung up. There. It was done. The die was cast. Whatever was going to happen would happen... starting tomorrow morning, early tomorrow morning. Summer had just come in. Jake worked through the rest of June 21. He ate supper, then went right on working through the night. Lulu brought him cup after cup of coffee. After a while, yawning, she went home to bed. He worked on, behind blackout curtains that kept light from leaking out of the Gray House and showing where it was from the air. June 21 passed through to June 22. All that coffee made Jake's heart thud and soured his stomach. He gulped a Bromo-Seltzer and went on. At a quarter past three, the drone of airplane engines and the thunder of distant artillery- not distant enough; damn those Yankee robbers!- made him whoop for sheer glee. He'd waited so long. Now his day was here.

- p. 534.

Settling Accounts: In at the Death (2007)

- Soldiers, by an agreement between General Ironhewer and me, the troops of the Army of Kentucky have surrendered. That we are beaten is a self-evident fact, and we cannot hope to resist the bomb that hangs over our head like the sword of Damocles. Richmond is fallen. The cause for which you have so long and manfully struggled, and for which you have braved dangers and made so many sacrifices, is today hopeless. Reason dictates and humanity demands that no more blood be shed here. It is your sad duty, and mine, to lay down our arms and to aid in restoring peace. As your commander, I sincerely hope that every officer and soldier will carry out in good faith all the terms of the surrender. War such as you have passed through naturally engenders feelings of animosity, hatred, and revenge. But in captivity and when you return home a manly, straightforward course of conduct will secure the respect even of your enemies. In bidding you farewell, rest assured that you carry with you my best wishes for your future welfare and happiness. I have never sent you where I was unwilling to go myself, nor would I advise you to a course I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers. Preserve your honor, and the government to which you have surrendered can afford to be and, I hope, will be magnanimous."

- C.S. Army General George S. Patton's final address to the Army of Kentucky in July 1944, p. 339

- "Still very erect, he saluted his men. Some of them cried out his name. Others let loose with what they still called the Rebel yell. Tears now streaming down his face, Patton waited for the tumult to die down a little. Then he stepped into the ragged ranks of the rest of the POWs. Defeated Confederate soldiers shook his hand and embraced him."

- p. 339

The Man With the Iron Heart (2008)

- Himmler steepled his fingers. "Well, Reinhard, what brings you up from Prague today?" His voice was fussy and precise, like a schoolmaster's.

- p. 7

- Finally the Reichsfuehrer said, "Well, you've given me a good deal to thin about. I can hardly deny that. We'll see what comes of it." "The longer we wait, the more trouble we'll have doing it properly," Heydrich warned. "I understand that," Himmler said testily. "I have to make sure I can get it moving without... undue difficulties, though." "As you say, sir!" Heydrich was all obedience, all subordination. Why not? Himmler played the cards close to his chest, but Heydrich was pretty sure he'd won.

- p. 11

- He and Don came up to the corpse of the German truck. The scrounger who'd been messing around there was gone. "Who's that asshole gonna sell his scrap to?" Charlie said. "Us- you wait and see. We're dumb enough to pay good money to put these mothers back on their feet now that we stomped 'em." "Yeah, that's like us, all right," Dom agreed. "We-" The truck blew up. Next thing Charlie knew, he was sprawled on the ground a surprisingly long way from the road. Dom- no, a piece of Dom- lay not far away. Charlie tried to reach out. His arm didn't want to work. When he looked down at what was left of himself, he understood why. It didn't hurt. Then, all at once, it did. His shriek bubbled through the blood filling his mouth. Mercifully, blackness enfolded him.

- p. 17

- What will we do when they start capturing our people?" Klein asked. "They will, you know, if they haven't by now. Things go wrong." Heydrich's fingers drummed some more. He didn't worry about the laborers who'd expanded this redoubt- they'd all gone straight to the camps after they did their work. But captured fighters were indeed another story. He sighed. "Things go wrong. Ja. If they didn't, Stalin would be lurking somewhere in the Pripet Marshes, trying to keep his partisans fighting against us. We would've worked Churchill to death in a coal mine." He barked laughter. "The British did some of that for us, when they threw the bastard out of office last month. And we'd be getting ready to fight the Amis on their side of the Atlantic. But... things went wrong." "Yes, sir." After a moment, Klein ventured, "Uh, sir- you didn't answer my question." "Oh. Prisoners." Heydrich had to remind himself what his aide was talking about. "I don't know what to do, Klein, except make sure our people all have cyanide pills." "Some won't have the chance to use them. Some won't have the nerve," Klein said. Not many men had the nerve to tell Reinhard Heydrich the unvarnished truth. Heydrich kept Klein around not least because Klein was one of those men. They were useful to have. Hitler would have done better had he seen that. Heydrich recognized the truth when he heard it now; one more thing Hitler'd had trouble with.

- p. 56-57

- Eisenhower climbed down from his jeep. Two unsmiling dogfaces with Tommy guns escorted him to a lectern in front of the church's steps. The sun glinted from the microphones on the lectern... and from the pentagon of stars on each of Ike's shoulder straps. "General of the Army" was a clumsy title, but it let him deal with field marshals on equal terms. He tapped a mike. Noise boomed out of speakers to either side of the lectern. Had some bright young American tech sergeant checked to make sure the fanatics didn't try to wire explosives to the microphone circuitry? Evidently, because nothing went kaboom. "Today it is our sad duty to pay our final respects to one of the great soldiers of the 20th century. General George Smith Patton was admired by his colleagues, revered by his troops, and feared by his foes," Ike said. If there were a medal for hypocrisy, he would have won it then. But you were supposed tp only speak well of the dead. Lou groped for the Latin phrase, but couldn't come up with it. "The fear our foes felt for General Patton is shown by the cowardly way they murdered him: from behind, with a weapon intended to take out tanks. They judged, and rightly, that George Patton was worth more to the U.S. Army than a Stuart or a Sherman or a Pershing," Eisenhower said. "Damn straight, muttered the man standing next to Lou. He wore a tanker's coveralls, so his opinion of tanks carried weight. Tears glinted in his eyes, which told all that needed telling if his opinion of Patton.

- p. 61-62

- "I have one more message for you men, and for the SS goons who skulk in the woods and in the darkness," Eisenhower said. "It's very simple. We are going to stay here as long as it takes to make sure Germany can never again trouble the peace of the world." He probably expected more cheers then. He got... a few. Lou was one of the men who clapped. The guy in the tanker's coveralls edged away, as if afraid he had something contagious. That saddened him without much surprising him. He wondered how many of the others who applauded there were also Jewish. Quite a few, unless he missed his guess. Yes, Eisenhower had looked for more in the way of approval there. He'd acted professionally grim before. Now his eyes narrowed and the corners of his mouth turned down. He wasn't just grim any more; he was pissed off.

- p. 63

- Lieutenant General Vlasov had looked and acted like a son of a bitch the last time Bokov and Shteinberg called on him. He seemed even less friendly now. For twenty kopeks, his expression said, both of the other NKVD men could find out how they liked chopping down spruces in the middle of Siberian winter.

- p. 412

- "I know what the two of you are here for," Vlasov rasped. "You're going to try and talk me into sucking the Americans' cocks." "No, Comrade General, no. Nothing like that," Shteinberg said soothingly. Yes, Comrade General, yes. Just like that, Vladimir Bokov thought fiercely. He wanted to watch Vlasov squirm. Maybe they could have kept the crash from happening if only the miserable bastard had put his ass in gear. "Don't bother buttering me up, zhid," Vlasov said. "Nothing but a waste of time." "However you please... sir." Moisei Shteinberg held his voice under tight control. "My next move, if you keep dicking around with us, is to write to Marshal Beria and let him know how you're obstructing the struggle against the Heydrichite bandits." "You wouldn't dare!" General Vlasov bellowed. "Yes, I would. I've already done it," Shteinberg said. "And if anything happens to me, the letter goes to Moscow anyway. I've taken care of that, too... sir." "Fuck your mother hard!" "Maybe my father did," Shteinberg answered calmly. "But at least I know who he was... sir." Could looks have killed, Yuri Vlasov would have shouted for men to come and drag two corpses out of his office.

- p. 412-413

- "If it works, he'll take the credit," Bokov warned once they were safely outside NKVD headquarters. "Oh, sure," Shteinberg agreed. "But he'd do that anyway." Bokov laughed, not that his superior was joking- or wrong.

- p. 413

- Outside the building, Lou smoked a last cigarette and shot the shit with one of the German gendarmes who'd be taking over the place once the Americans were gone. Rolf was a pretty good guy. He'd been a corporal during the war- but Wehrmacht, not Waffen-SS. In his dyed-black U.S. fatigues and American helmet, he looked nothing like a German soldier. So Lou tried to tell himself, anyhow. "We will miss you when you go," the gendarme said. "You are the only thing standing between us and chaos." "You guys will do fine on your own," Lou answered. You always assured a sickroom patient, even- especially- when you didn't think he'd make it.

- p. 528

- Rolf Halbritter coughed from the dust the retreating convoy kicked up. He shook his head in wonder not far from awe. The Amis were really and truly going- no, really and truly gone. Which meant... He had a badge pinned on the underside of his collar, where it didn't show. Now he could wear it openly agian. It was round, with a red outer ring that carried a legend in bronze letters: NATIONALSOZIALISTISCHE DEUTSCHE ARBEITERPARTEI. The white inner circle held a black swastika. Every Party member had one just like it. Pretty soon, they'd all be showing it, too.

- p. 528

- There really was a German resistance movement after V-E Day. It was never very effective; it got off to a very late start, as the Nazis took much longer than they might have to realize they weren't going to win the straight-up war. And it was hamstrung because the Wehrmacht, the SS, the Hitler Youth, the Luftwaffe, and the Nazi Party all tried to take charge of it- which often meant, for all practical purposes, no one took charge of it. By 1947, it had mostly petered out.

- Historical Note, p. 531

The United State of Atlantis (2008)

- A horsefly can't do a horse much real damage, but it can drive it wild anyhow.

- p. 127

- People you don't like are pigheaded. Your friends are stubborn, or hold to their purpose.

- p. 184

External links

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.