Evangelicalism, evangelical Christianity, or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, trans-denominational movement within Protestant Christianity which maintains the belief that the essence of the Gospel consists of the doctrine of salvation by grace, solely through faith in Jesus's atonement. Evangelicals believe in the centrality of the conversion or "born again" experience in receiving salvation, in the authority of the Bible as God's revelation to humanity, and in spreading the Christian message.

Its origins are usually traced to 1738, with various theological streams contributing to its foundation, including English Methodism, the Moravian Church (in particular its bishop Nicolaus Zinzendorf and his community at Herrnhut, and German Lutheran Pietism Preeminently, John Wesley and other early Methodists were at the root of sparking this new movement during the First Great Awakening; which marked the rise of evangelical religion in colonial America.

Today, evangelicals are found across many Protestant branches, as well as in various denominations not subsumed to a specific branch.

Quotes

If you didn't look at them separately," he added, "if you lumped them all together, you would miss a big part of the story about the connections and the interrelations of religion, race, and politics in the U.S.. ~ Greg Smith

- The study of religion’s role as a political force in American politics presents an intriguing puzzle. Why are conservative Christians perceived as such a potent electoral force when their rates of political participation are often lower than what is observed in the general population? From the writings of both political scientists and pundits, one might be led to believe that white evangelical Protestants are a wildly participatory religious group. For example, the standard account of the recent history of how religion and politics intersect in the U.S. generally includes the assertion that evangelical Christians were awakened from political quiescence some time in the late 1970s (Dionne,1991; Wald, 2003; Wilcox, 1996) In the words of Guth and Green, ‘‘The common view is that clergy and lay activists in theologically conservative Protestant churches represent a large, hyperactive and newly mobilized cadre of traditionalists’’(1996, p. 118). However, while there has indisputably been a rise in the role religiously conservative groups play in contemporary politics, this has simply not been accompanied by an increase in the political participation of individual religious conservatives (Miller and Shanks, 1996, P. 231).

- David E. Campbell, “ACTS OF FAITH: Churches and Political Engagement”, Political Behavior, Vol. 26, No. 2, (June 2004); pp. 155-156.

- While there are many ways to distinguish among America’s myriad religious denominations, one that has been demonstrated to have particular utility is there cognition that there is a sharp divide among Protestants between those who belong to evangelical and mainline denominations. The key differences are described by Steensland et al. (2000):Mainline denominations have typically emphasized an accommodating stance toward modernity, a proactive view on issues of social and economic justice, and pluralism in their tolerance of varied individual beliefs. Evangelical denominations have typically sought to more separation from the broader culture, emphasized missionary activity and individual conversion, and taught strict adherence to particular religious doctrines.

- David E. Campbell, “ACTS OF FAITH: Churches and Political Engagement”, Political Behavior, Vol. 26, No. 2, (June 2004); p. 157.

- The claim that participation in an evangelical Protestant church diminishes participation in political activity diverges from the current literature in two ways. First, the general relationship between religious and political involvement is a strong positive correlation. Putnam succinctly states the conventional wisdom by noting that ‘‘churchgoers are substantially more likely to be involved in secular organizations, to vote and participate politically in other ways’’ (Putnam, 2000). Wald (2003) discusses a small library of studies which draw this conclusion (Cassel, 1999; Hougland and Christensen, 1983; Maca-luso and Wanat, 1979; Martinson and Wilkening, 1987; Rosenstone andHansen, 1993). Such studies provide a number of complementary explanations for the positive relationship, including the development of civic skills (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady, 1995), experience in democratic decision-making (Peterson, 1992), and development of community attachments (Strateet al., 1989). Wald notes a unifying theme across these studies, however, that applies to this analysis as well, ‘‘Churches serve as social networks that seem to draw participants into public affairs’’ (2003, p. 37). The argument here is that while evangelicals’ tight social networks facilitate sporadic mobilization, the process by which those networks are formed can also serve to deflate their levels of political activity.

- David E. Campbell, “ACTS OF FAITH: Churches and Political Engagement”, Political Behavior, Vol. 26, No. 2, (June 2004); p. 159.

- Evangelicalism is highly fragmented and its political effects cannot be read off from its religious doctrines. Fragmentation means that its direct political impact is always smaller than might be hoped or feared and therefore no evangelical neo-Christendom potentially dangerous to democracy is feasible. In addition, it does not seem that Third-World evangelicalism will line up with the First-World Christian right on many issues. But the results for democracy are paradoxical. Totalitarian regimes or movements are firmly resisted, as are non-Christian religious nationalisms, but authoritarian regimes which do not impinge on evangelical religion may not always be. The evangelical world is too fissured and independent to provide a firm basis for nation-wide movements advocating major political change. It is thus less ‘use’ during democratic transitions than during periods of democratic consolidation.

- Paul Freston, “Evangelical protestantism and democratization in contemporary Latin America and Asia”, (01 Mar 2004, Published online: 24 Jan 2007). p. 21.

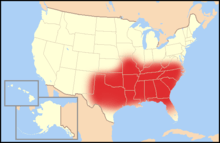

- "White evangelical protestants are some of the most reliably conservative and Republican voters in the electorate," said Greg Smith, associate director of research at Pew. "African-American protestants, on the other hand, are some of the most strongly and consistently Democratic voters in the electorate."

"If you didn't look at them separately," he added, "if you lumped them all together, you would miss a big part of the story about the connections and the interrelations of religion, race, and politics in the U.S."- Danielle Kurtzleben, “Are You An Evangelical? Are You Sure?”, NPR, (December 19, 2015).

- "The term 'evangelical' has a very broad set of meanings in Christianity. In its origins, it refers to the evangel, which is a Greek word from the New Testament that refers to the 'good news,' or the gospel of Jesus Christ," said John Green, professor of political science at the University of Akron and an expert in the intersection of [politics]] and religion, in an August interview.

"In some sense, all Christians have an element of being an evangelical, because they all share to one degree or another those basic Christian beliefs," he added.- Danielle Kurtzleben, “Are You An Evangelical? Are You Sure?”, NPR, (December 19, 2015).

- You could dismiss this all as pedantry — that using "evangelicals" as a catch-all term for a certain group of Christians is a harmless shorthand, like calling all tissues Kleenexes or all sodas Coke. But then, consider how pollsters and pundits often separate white and black evangelicals based on their political views. That's one piece of a bigger problem: the degree to which "evangelical" may be becoming redefined by its political associations.

"While evangelical, in this traditional sense, is really a religious word," Green said, "it's become very strongly associated with Republican and conservative politics, because since the days of Ronald Reagan up until today, that group of believers have moved in that direction politically."

Indeed, that association has grown stronger in the last couple of decades. In the late 1980s, around one-third of white evangelicals identified as Republican, according to Pew. Earlier this year, Pew found that 68 percent of white evangelicals do.- Danielle Kurtzleben, “Are You An Evangelical? Are You Sure?”, NPR, (December 19, 2015).

- 1976 was the first year Gallup asked Americans if they had been "born again," as Hackett wrote in a 2008 paper. The organization's measurement methods varied over the next decade, but in 1986, the organization first asked the "born-again or evangelical" question that it uses today. Over that time, self-proclaimed born-again Christians and evangelicals helped reshape the political landscape. In 1976, the born-again former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter was elected to the White House. After that, political interest in evangelicals and born-again Christians remained, but Rev. Pat Robertson's 1988 second-place finish in the Iowa caucuses in particular made it clear that white evangelicals were swinging Republican. Outspoken Christians like George W. Bush continued the trend of winning over these conservative Christians, and targeting those voters is still a key campaign strategy for politicians like Mike Huckabee and Rick Santorum.

- Danielle Kurtzleben, “Are You An Evangelical? Are You Sure?”, NPR, (December 19, 2015).

Antony Loewenstein, “US evangelicals in Africa put faith into action but some accused of intolerance”, The Guardian, (18 Mar 2015)

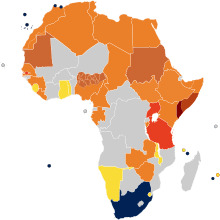

- Africa is by and large conservative, and many poor countries are susceptible to charity with a socially conservative agenda. It’s within this context that many US evangelical churches go to Africa to win the battles that are being lost at home. Many of them subscribe to the dominionist movement, which supports turning secular governments into Christian theocracies. They pressure NGOs not to accept Christians in same-sex marriages. Missionaries have traversed the length and breadth of Africa for centuries, so this 21st century American campaign is just the latest in a long line of foreign influence.

- Rev Jackson George Gabriel, the curate of the Episcopal Church of South Sudan and Sudan, tells me that he welcomes outside encouragement, confirming that the American branch of his church “are telling us to stand firm against homosexuality”. In a country where President Salva Kiir has said that homosexuality will “always be condemned by everybody”, and where the public shaming of gay South Sudanese by local tabloid media is growing, his stance enjoys a lot of support.

- Part of the agenda of US evangelical churches is explored in a 2014 report by the Rev Kapya Kaoma called American Culture Warriors in Africa: A Guide to the Exporters of Homophobia and Sexism, which is endorsed by Desmond Tutu. Kaoma is an Anglican priest from Zambia now living and working in the US with the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts due to threats against his life. His work paints a picture of the myriad of US groups and their African allies who, he says, are “seeking to impose their intolerant – and even theocratic – interpretations of Christianity on the rest of the world”.

- In Uganda, American evangelicals have partnered, and sometimes trained, local pastors and church leaders to push extreme, anti-gay legislation. Leading newspapers outed people as “top homosexuals”, such as Frank Mugisha, and gay men and women face discrimination and violence.

- Bishop Senyonjo of Uganda, a rare voice in his country advocating for LGBT rights, also hopes that churches will change their ways. “Evangelicals, wherever they come from the US and elsewhere, should bring good news of inclusion and love of God rather than sowing seeds of discrimination and hate,” he tells me before adding: “The Gospel is supposed to be liberating to marginalised people.”

Anthony Gill, “Weber in Latin America: Is Protestant Growth Enabling the Consolidation of Democratic Capitalism?”, Washington.edu

- Since the 1930s, a number of countries in Latin America have experienced rapid growth in the expansion of evangelical Protestantism. Has this religious change produced concomitant changes in the political landscape? Some scholars have seen the possibility of a Weberian ‘Protestant ethic’ emerging, making the region more amenable to democratic capitalism. Others have argued that the ‘otherworldly’ nature of these new (predominantly Pentecostal) evangelicals lends itself to a more apolitical outlook and a deference to authoritarian rule. Using survey data from four countries– Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico – this article concludes that denominational affiliation has little effect on political attitudes.

- p.1.

- While Protestantism in Europe and the United States has tended to be linked to an active support of political democracy, the same has not been universally true for Latin American Protestants. Ireland notes that the‘prevailing stereotype of Pentecostal crentes [believers] is that they are apolitical conservatives who leave the injustices of the world to the Lord’s care, privatizing public issues and giving implicit support to authoritarian political projects’. After providing evidence from interviews with two Brazilian Pentecostal he concludes that this stereotype is largely true. His reasoning is largely derived from the fact that Pentecostal theology places far greater emphasis on achieving rewards in the afterlife than in the present world. Such a mindset creates a predilection for political apathy and acceptance of the status quo, which in Latin America has often been authoritarian. Deiros echoes this assertion by claiming that "fundamentalists tend to consider evangelism – in its narrower or ‘spiritual’ sense – to be the only legitimate activity of the church and remain wary of current trends toward church involvement in political affairs. They fear that such involvement may lead the church away from its central evangelistic mission into a substitute religion of good works, humanitarianism, and even political agitation...Because fundamentalists place the end of history outside of history, their social conscience is subdued, and their organizations reinforce this oppressed conscience by supplying a sociocultural structure which attributes a sacred character to the state of oppression...Any claim for justice or liberation from oppression is transferred to a remote eschatological future."

This stereotype is augmented by several high profile cases wherein some evangelicals supported dictators or political leaders with an authoritarian bent: Efrain Rios Montt (Guatemala); Jorge Serrano Elias (Guatemala); the ARENA party (El Salvador); Augusto Pinochet (Chile) and Alberto Fujimori(Peru). For example, Smith and Fleet argue that in Chile, during the Pinochet years, Catholics and mainline Protestant denominations, most of which were opposed to the dictatorship, worked closely together. In contrast, the new denominations (Pentecostals as well as [Jehovah’s] Witnesses and Mormons) were more favorably disposed to the military government.- pp. 4-5.