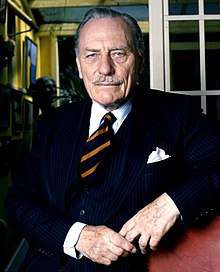

John Enoch Powell (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a British politician and Conservative Party MP between 1950 and February 1974, and an Ulster Unionist MP between October 1974 and 1987.

Quotes

1930s

- [In Italy, when every sentence is liable to be scanned for traces of anti-Fascist sentiment] it is obviously safer to begin by choosing a more congenial subject than a free Athens or a free Rome. In Germany the effect of National-Socialism has been the opposite. Racial doctrines and political antipathy to the whole Roman Empire and its cognate ideas have had the result of discouraging study of the Italic peoples and of Rome, the mistress of the world. On the other hand, a peculiar kinship has been detected between the ancient Greeks and modern Germans. Not only the Greek civilization in general, but Thucydides in particular, has proved exceptionally congenial. The intensely political outlook of Thucydides may be made serviceable to a doctrine which asserts the absolute dominion of the State over every phase of individual existence; and, as the more striking figures of Caesar and Augustus had already been captured as prototypes by Mussolini, Hitler might well be made to look very like Pericles—or Pericles, rather, to look like Hitler.

- "The War and its Aftermath in their influence on Thucydidean Studies", address given to the Classical Association at Westminster School (4 January 1936), from The Times (6 January 1936), p. 8.

- The world has recently been treated for nearly a decade to the unusual spectacle of a great empire deliberately taking every possible step to secure its own destruction, because its citizens were so obsessed by prejudice, or incapable of thinking for themselves, as never to perform the few logical steps necessary for proving that they would shortly be involved in a guerre à outrance, which could be neither averted nor escaped.

- Powell's inaugural lecture as Professor of Greek (7 May 1938), from Greek in the University. An Inaugural Lecture (Oxford University Press, 1938), p. 9.

- I do here in the most solemn and bitter manner curse the Prime Minister of England [sic] for having cumulated all his other betrayals of the national interest and honour, by his last terrible exhibition of dishonour, weakness and gullibility. The depths of infamy which our accurst "love of peace" can lower us are unfathomable.

- Letter to his parents (18 September 1938) after Neville Chamberlain's meeting with Adolf Hitler at Berchtesgaden, from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 47.

- It is the English, not their Government; for if they were not blind cowards, they would lynch Chamberlain and Halifax and all the other smarmy traitors.

- Letter to his parents (27 June 1939), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 53.

1940s

- The thought struck me for the first time today that our duty to our country may not terminate with the peace – apart, I mean, from the duty of begetting children to bear arms for the King in the next generation. To be more explicit, I see growing on the horizon the greater peril than Germany or Japan ever were; and if the present hostilities do not actually merge into a war with our terrible enemy, America, it will remain for those of us who have the necessary knowledge and insight to do what we can where we can to help Britain be victorious again in her next crisis.

- Letter to his parents (16 February 1943), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 75.

- You have never expressed any decided political opinions, and indeed I do not know if or how far you assent to the proposition that almost unlimited sacrifices of individual life and happiness are worth while to preserve the unique structure of power of which the keystone (the only conceivable and indispensable keystone) is the English Crown. I for my part find it the nearest thing in the world to an absolute (as opposed to a relative) value: it is like the outer circle that bound my universe, so that I cannot conceive anything beyond it.

- Letter to his parents (9 March 1943), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 75.

- The continuance of India within the British Empire is essential to the Empire's existence and is consequently a paramount interest both of the United Kingdom and of the Dominions...for strategic purposes there is no half-way house between an India fully within the Empire and an India totally outside it...Should it once be admitted or proved that Indians cannot govern themselves except by leaving the Empire – in other words, that the necessary goal of political development for the most important section of His Majesty's non-European subjects is independence and not Dominion status – then the logically inevitable outcome will be the eventual and probably the rapid loss to the Empire of all its other non-European parts. It would extinguish the hope of a lasting union between "white" and "coloured" which the conception of a common subjectship to the King-Emperor affords and to which the development of the Empire hitherto has given the prospect of leading...In discussion of the wealth of India it is usual to forget the principal item, which is four hundred millions of human beings, for the most part belonging to races neither unintelligent nor slothful...[British policy should be to] create the preconditions of democracy and self-government by as soon as possible making India socially and economically a modern state.

- Memorandum on Indian Policy (16 May 1946), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), pp. 104-105.

1950s

- We describe a Monarch by designating the territory of which he is Monarch. To say that he is Monarch of a certain territory and his other realms and territories is as good as to say that he is king of his kingdom. We have perpetrated a solecism in the title we are proposing to attach to our Sovereign and we have done so out of what might almost be called an abject desire to eliminate the expression "British." The same desire has been felt—though not by any means throughout the British Commonwealth—to eliminate this word before the term "Commonwealth." ... Why is it, then, that we are so anxious, in the description of our own Monarch, in a title for use in this country, to eliminate any reference to the seat, the focus and the origin of this vast aggregation of territories? Why is it that this "teeming womb of royal Kings," as Shakespeare called it, wishes now to be anonymous?

- Speech in the House of Commons (1 March 1953) against the Royal Titles Bill

- I believe a second factor which has weighed heavily in this matter is the attitude, or supposed attitude, of the United States. I confess that I am not greatly moved by this. Whatever may be the attitude of the American Government and public to the United Kingdom as such, my view of American policy over the last decade has been that it has been steadily and relentlessly directed towards the weakening and the destruction of the links which bind the British Empire together. [Cyril Osborne: "No!"] We can watch the events as they unfold and place our own interpretation on them. My interpretation is that the United States has for this country, considered separately, a very considerable economic and strategic use but that she sees little or no strategic use or economic value in the British Empire or the British Commonwealth as it has existed and as it still exists. Against the background I ask the House to consider the evidence of advancing American imperialism in this area from which they are helping to eliminate us.

- Speech in the House of Commons (5 November 1953) on the British evacuation of the Suez Canal.

- There is no possibility of arguing that the present composition of the House of Lords can be justified either by logic or by reference to any preconceived constitutional theory. It is the result of a long, even a tortuous, process of historical evolution. Its authority rests upon the acceptance of the result, handed down to our time, of that historical process. It is the authority of acceptance, the authority of what Burke called "prescription". The House of Lords shares that characteristic with many of our most cherished and important institutions. Trial by jury, for example, is not to be justified in logic; it does not rest upon statute; it came to us by a strange historical evolution out of the sworn witnesses of a neighbourhood. Neither logic nor statute nor theory is a basis of that other hereditary institution by which it comes about that a young woman holds sway over countless millions. The authority of this House itself does not, in the last resort, rest upon any logic in the principles upon which we are formed or elected: it rests upon the acceptance by the nation of an institution the history of which cannot be divorced or torn out of the context of the history of the nation itself.

- Speech in the House of Commons (12 February 1958) against the Life Peerages Bill

- I would say that it is a fearful doctrine, which must recoil upon the heads of those who pronounce it, to stand in judgment on a fellow human-being and to say, "Because he was such-and-such, therefore the consequences which would otherwise flow from his death shall not flow." ... Nor can we ourselves pick and choose where and in what parts of the world we shall use this or that kind of standard. We cannot say, "We will have African standards in Africa, Asian standards in Asia and perhaps British standards here at home." We have not that choice to make. We must be consistent with ourselves everywhere. All Government, all influence of man upon man, rests upon opinion. What we can do in Africa, where we still govern and where we no longer govern, depends upon the opinion which is entertained of the way in which this country acts and the way in which Englishmen act. We cannot, we dare not, in Africa of all places, fall below our own highest standards in the acceptance of responsibility.

- Speech in the House of Commons (27 July 1959) on the Hola Camp massacre

1960s

- There they stand, isolated, majestic, imperious, brooded over by the gigantic water-tower and chimney combined, rising unmistakable and daunting out of the countryside—the asylums which our forefathers built with such immense solidity to express the notions of their day. Do not for a moment underestimate their powers of resistance to our assault.

- Speech to the annual conference of the National Association of Mental Health in London (9 March 1961), quoted in The Times (10 March 1961), p. 8

- That power and that glory have vanished, as surely, if not as tracelessly, as the Imperial fleet from the waters of Spithead—in the eye of history, no doubt as inevitably as “Nineveh and Tyre”, as Rome and Spain. And yet England is not as Nineveh and Tyre, nor as Rome, nor as Spain. Herodotus relates how the Athenians, returning to their city after it had been sacked and burnt by Xerxes and the Persian army, were astonished to find, alive and flourishing in the blackened ruins, the sacred olive tree, the native symbol of their country. So we today at the heart of a vanished empire, amid the fragments of demolished glory, seem to find, like one of her own oak trees, standing and growing, the sap still rising from her ancient roots to meet the spring, England herself.

- Speech to the Royal Society of St George (22 April 1961), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), p. 144

- Thus our generation is one which comes home again from years of distant wandering. We discover affinities with earlier generations of English, generations before the “expansion of England”, who felt no country but this to be their own. ... Backward travels our gaze, beyond the grenadiers and the philosophers of the eighteenth century, beyond the pikemen and the preachers of the seventeenth, back through the brash adventurous days of the first Elizabeth and the hard materialism of the Tudors, and there at last we find them, or seem to find them, in many a village church, beneath the tall tracery of a perpendicular East window and the coffered ceiling of the chantry chapel. From brass and stone, from line and effigy, their eyes look out at us, and we gaze into them, as if we would win some answer from their inscrutable silence. “Tell us what it is that binds us together; show us the clue that leads through a thousand years; whisper to us the secret of this charmed life of England, that we in our time may know how to hold it fast.” What would they say? They would speak to us in our own English tongue, the tongue made for telling truth in, tuned already to songs that haunt the hearer like the sadness of spring. They would tell us of that marvellous land, so sweetly mixed of opposites in climate that all the seasons of the year appear there in their greatest perfection. ... They would tell us too of a palace near the great city which the Romans built at a ford of the River Thames...to which men resorted out of all England to speak on behalf of their fellows, a thing called “Parliament”, and from that hall went out their fellows with fur-trimmed gowns and strange caps on their heads, to judge the same judgments, and dispense the same justice, to all the people of England.

- Speech to the Royal Society of St George (22 April 1961), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), pp. 144–145

- One thing above all they assuredly would not forget; Lancastrian or Yorkist, squire or lord, priest or layman; they would point to the kingship of England, and its emblems everywhere visible. The immemorial arms, gules, three leopards or, though quartered late with France, azure, three fleurs de lis argent; and older still, the crown itself and that sceptred awe, in which Saint Edward the Englishman still seemed to sit in his own chair to claim the allegiance of all the English. Symbol, yet source of power; person of flesh and blood, yet incarnation of an idea; the kingship would have seemed to them, as it seems to us, to express the qualities that are peculiarly England's. The unity of England, effortless and unconstrained, which accepts the unlimited supremacy of Crown in Parliament so naturally as not to be aware of it; the homogeneity of England, so profound and embracing that the counties and the regions make it a hobby to discover their differences and assert their peculiarities; the continuity of England, which has brought this unity and this homogeneity about by the slow alchemy of centuries.

- Speech to the Royal Society of St George (22 April 1961), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), p. 145

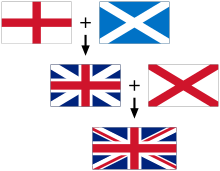

- For the unbroken life of the English nation over a thousand years and more is a phenomenon unique in history. ... Institutions which elsewhere are recent and artificial creations, appear in England almost as works of nature, spontaneous and unquestioned. The deepest instinct of the Englishman—how the word “instinct” keeps forcing itself in again and again!—is for continuity; he never acts more freely nor innovates more boldly than when he most is conscious of conserving or even of reacting. From this continuous life of a united people in its island home spring, as from the soil of England, all that is peculiar in the gifts and the achievements of the English nation, its laws, its literature, its freedom, its self-discipline. ... And this continuous and continuing life of England is symbolised and expressed, as by nothing else, by the English kingship. English it is, for all the leeks and thistles and shamrocks, the Stuarts and the Hanoverians, for all the titles grafted upon it here and elsewhere, “her other realms and territories”, Headships of Commonwealths, and what not. The stock that received all these grafts is English, the sap that rises through it to the extremities rises from roots in English earth, the earth of England's history.

- Speech to the Royal Society of St George (22 April 1961), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), pp. 145–146

- In my early twenties I read all Nietzsche—not just the main works but the minor works as well, all of them, and every scrap of published correspondence. Nietzsche alone of men out of books has a share in the loyalty and affectionate gratitude which otherwise belongs only to living teachers.

- 'Thin But Thorough', The Times (27 September 1962), p. 15

- ....the memory of big experiences in the world of books is flavoured with the tang of the physical setting in which they happened. I shall never be able to dissociate Ecce Homo from the old flying-boat route to the Antipodes. ... Or again, the long avenues of thought that have led from Frazer's Golden Bough seem to start physically in front of the dining-room fireplace of the home where as a boy of 15 I sat hour after hour absorbing first the one-volume abridgement and then the three-volume edition. I cannot imagine how different my mental and religious life would have been if the impact of J. G. Frazer had come at another time or not at all.

- 'Thin But Thorough', The Times (27 September 1962), p. 15

- Then, about the same time, there was the detonation of Sartor Resartus. ... It was not only the revelation of Carlyle; it was headlong precipitation into the ocean of German reading and German thinking, where I was destined to voyage long after romantic and uncritical enthusiasm had perished for ever with the rise of Nazism. ... The happiest and most glorious hours of my life with books—confess it I must—have been with German books. ... there was Schopenhauer, carried up and down daily for months on the Sydney trams. There was Lessing, Hölderlin even; above all, and above all, there was Goethe. Was, and still is; for a spare 10s. note is as likely to this day to be exchanged for a volume of Goethe as for anything else that sits on a book-seller's shelves.

- 'Thin But Thorough', The Times (27 September 1962), p. 15

- We are a capitalist party. We believe in capitalism. When we look at the astonishing material achievements of the West, at our own high and rising physical standard of living, we see these things as the result, not of compulsion or government action or the superior wisdom of a few, but of that system of competition and free enterprise, rewarding success and penalising failure, which enables every individual to participate by his private decisions in shaping the future of his society.

- Speech in Bromsgrove (6 July 1963), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), p. 25

- Society is much more than a collection of individuals acting together, even through the complex and subtle mechanisms of the free economy, for material advantage. It has an existence of its own; it thinks and feels; it looks inwards, as a community to its own members; it looks outwards as a nation, into a world populated by other societies, like or unlike itself. The Tory Party, with its deep sense of history, has always concerned itself especially with these two aspects of society, and I believe that the British people would instinctively and rightly reject a philosophy which offered them just an economic machine, however efficient and successful.

- Speech in Bromley (24 October 1963), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), pp. 4–5

- It is no accident that the Labour Party of 1964 should share this craving for autarchy, for economic self-sufficiency, with the pre-war Fascist régimes and the present-day Communist states. They are all at heart totalitarian.

- Speech to the Dulwich Conservative Association (29 February 1964), from A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), p. 75

- Now, there is one set of market forces, supremely important to Britain, which lie outside the reach of even a Socialist government. These are world market forces. Whatever government we have in this country, the rest of the world will only buy from us what it cannot get elsewhere cheaper and better. If our prices are high or our goods not the right ones, it will be no use saying: “Oh, but we have decided not to be ruled by market forces beyond our control.” The rest of the world would laugh in our faces. And what sheer nonsense and utter hypocrisy it is for a country dependent on selling a fifth of its product abroad to pretend not to “be ruled by market forces”!

- Speech in Wolverhampton (25 September 1964), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), p. 11

- When a man offers to sell you something at less than its market price, it is a pretty good sign that you are about to be swindled.

- Speech in Aldridge (2 October 1964), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), p. 64

- In the end, the Labour party could cease to represent labour. Stranger historic ironies have happened than that.

- Article for The Sunday Telegraph, citing the swing to the Conservatives in his constituency and others with large working-class electorates (18 October 1964), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 364

- Before more months or years are spent by Ministers, by economic staffs, by industrialists and by trade unionists, in a pursuit which is as foredoomed to futility as filling a sieve or making a rope of sand, it is time to call a halt, and to declare in round and unmistakeable terms that an incomes policy, in any relevant or useful sense, does not and cannot exist—except perhaps in a communist dictatorship.

- Speech in Birmingham (28 November 1964), quoted in A Nation Not Afraid. The Thinking of Enoch Powell (B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965), p. 100

- If the Western nations were to confer on the rest of mankind not, as at present, just a tiny fraction of their goods and capital, but were, literally, in the words of the epistle, to ‘bestow all their goods to feed the poor’ their wealth would only disappear, like a snowflake on boiling water, into the maw of these vast and astronomically increasing populations, and the outcome would be a common level of poverty and incompetence. Whence, then, if from anywhere, are the means of improvement to come? There is only one possible answer: essentially from within. The investment and the initiative which made possible the development of the Western economies was not subscribed or donated from outside; it came from within. The rise of Japan, in far less than a century from Admiral Perry's arrival, to challenge the Western countries in technology and production, was not because she was spoon-fed with grants and uneconomic loans from a benevolent Europe or America: it was due to the spirit and character of her people and their aptitude and appetite to learn. The great, the only truly beneficent gift we have to offer is the example of that which has made the West productive – capitalism and enterprise. But it is a gift which implies the power and will to receive it: and that, although we can teach and demonstrate by precept and by example, it is not in our power simply to confer. In short, the secret of aid to the developing countries is not capital itself: it is capitalism.

- Speech to the Canada Club in Manchester (10 December 1965), quoted in Freedom and Reality (Elliot Right Way Books, 1969), pp. 268–269

- Under the Labour Government in the last eighteen months Britain has behaved, perfectly clearly and perfectly recognizably, as an American satellite.

- Speech in Falkirk (26 March 1966) during the general election campaign, quoted in Andrew Roth, Enoch Powell: Tory Tribune (1970), p. 337

- The happiest and most glorious hours of my life with books have been with German books.

- The Observer (24 April 1966)

- For over ten years, from about 1954 to 1966, Commonwealth immigration was the principal, and at times the only, political issue in my constituency in Wolverhampton. Between those dates entire areas were transformed by the substitution of a wholly or predominantly coloured population for the previous native inhabitants, as completely as other areas were transformed by the bulldozer. My uppermost feeling on looking back upon those years is of astonishment that this event, which altered the appearance and life of a town and had shattering effects on the lives of many families and persons, could take place with virtually no physical manifestations of antipathy. This speaks volumes for the steadiness and tolerance of the natives. Acts of an enemy, bombs from the sky, they could understand; but now, for reasons quite inexplicable, they might be driven from their homes and their property deprived of value by an invasion which the Government apparently approved and their fellow-citizens – elsewhere – viewed with complacency. Those were the years when a ‘For Sale’ notice going up in a street struck terror into all its inhabitants. I know; for I live within the proverbial stone’s throw of streets which ‘went black’.

- 'Facing Up to Britain's Race Problem', The Daily Telegraph (16 February 1967), quoted in Still to Decide (Elliot Right Way Books, 1972), pp. 294–295

- In my own constituency (where I estimate that about 10 per cent of the population are immigrants from Asia or the Caribbean) I have the impression that, as no doubt elsewhere, the first phase, the sudden impact of Commonwealth immigration, is over. I am going to prophesy, however, that there will be subsequent phases, when the problem will resume its place in public concern and in a more intractable form, when it can no longer be dealt with simply by turning the inlet tap down or off. Long before the coloured population reaches 5 per cent of the total, a proportion will have filtered into the general population, mingled with it in occupation, residence, habits and intermarriage. On the other hand, the rest, numerically perhaps much the greater part, will be in larger or smaller colonies, in certain areas and cities, more separated than now in habits, occupation and way of life. The irregular pattern of population and living which grew up higgledy-piggledy in the early years of immigration will have been tidied up. It is for these colonies, and the problems thereby entailed on our descendants, that they will curse the improvident years, now gone, when we could have avoided it all.

- 'Facing Up to Britain's Race Problem', The Daily Telegraph (16 February 1967), quoted in Still to Decide (Elliot Right Way Books, 1972), p. 295

- Once you go nuclear at all, you go nuclear for good; and you know it. Here is the parting of the ways, for from this point two opposite conclusions can be drawn. One is that therefore there can never again be serious war of any duration between Western nations, including Russia—in particular, that there can never again be serious war on the Continent of Europe or the waters around it, which an enemy must master in order to threaten Britain. That is the Government's position. The other conclusion, therefore, is that resort is most unlikely to be had to nuclear weapons at all, but that war could nevertheless develop as if they did not exist, except of course that it would be so conducted as to minimise any possibility of misapprehension that the use of nuclear weapons was imminent or had begun. The crucial question is whether there is any stage of a European war at which any nation would choose self-annihiliation in preference to prolonging the struggle. The Secretary of State says, "Yes, the loser or likely loser would almost instantly choose self-annihiliation." I say, "No. The probability, though not the certainty, but surely at least the possibility, is that no such point would come, whatever the course of the conflict."

- Speech in the House of Commons (1 March 1967)

- It is advertising that enthrones the customer as king. This infuriates the socialist...[it is] the crossing of the boundary between West Berlin and East Berlin. It is Checkpoint Charlie, or rather Checkpoint Douglas, the transition from the world of choice and freedom to the world of drab, standard uniformity.

- Attacking the Labour President of the Board of Trade, Douglas Jay, who wanted to standardise packaging for detergents. (The Daily Telegraph 29 April 1967); from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 430

- Integration of races of totally disparate origins and culture is one of the great myths of our time. It has never worked throughout history. The United States lost its only real opportunity of solving its racial problem when it failed after the Civil War to partition the old Confederacy into a "South Africa" and a "Liberia".

- Remark to an American visitor shortly after Powell's return to London from his first visit to the United States in October 1967, as quoted in Andrew Roth, Enoch Powell: Tory Tribune (1970), p. 341

- Often when I am kneeling down in church, I think to myself how much we should thank God, the Holy Ghost, for the gift of capitalism.

- Speech to a luncheon of lobby correspondents (c. early 1968), quoted in T. E. Utley, Enoch Powell: The Man and his Thinking (1968), p. 114

- There is a sense of hopelessness and helplessness which comes over persons who are trapped or imprisoned, when all their efforts to attract attention and assistance bring no response. This is the kind of feeling which you in Walsall and we in Wolverhampton are experiencing in the face of the continued flow of immigration into our towns. We are of course in a minority – make no mistake about that. Out of over 600 parliamentary constituencies perhaps less than 60 are affected in any way like ourselves. The rest know little or nothing and, we might sometimes be tempted to feel, care little or nothing. Only this week a colleague of mine in the House of Commons was dumbfounded when I told him of a constituent whose little daughter was now the only white child in her class at school. He looked at me as if I were a Member of Parliament for central Africa, who had suddenly dropped from the sky into Westminster. So far as most people in the British Isles are concerned, you and I might as well be living in central Africa for all they know about our circumstances.

- Speech in Walsall (9 February 1968), quoted in Still to Decide (Elliot Right Way Books, 1972), p. 290

- Some problems are unavoidable. Some evils can be coped with to a certain extent, but not prevented. But that a nation should have saddled itself, without necessity and without countervailing benefit, with a wholly avoidable problem of immense dimensions is enough to make one weep. That the same nation should stubbornly persist in allowing the problem, great as it already is, to be magnified further, is enough to drive one to despair.

- Speech in Walsall (9 February 1968), quoted in Still to Decide (Elliot Right Way Books, 1972), p. 290

- It is no kindness on the part of politicians to minimize the size which those problems will assume, even if from now onwards every possible legislative and administrative action is taken to limit it. To draw attention to those problems and face them in the light of day is wiser than to apply the method of the ostrich which rarely yields a satisfactory result – even to ostriches. We have just been seeing in Wolverhampton the cloud no bigger than a man's hand in the shape of communalism. Communalism has been the curse of India and we need to be able to recognize it when it rears its head here. Large numbers of Sikhs, who had been serving the Wolverhampton Corporation voluntarily and contentedly, have found themselves against their will made the material for communal agitation. They have the same right as anyone else to decide which if any of the rules of their sect they will keep, and they had found no difficulty in entering the Corporation's employment and complying with the same rules as their fellow employees. For those who took a different and a stricter view there were plenty of other opportunities of employment. It will be the opposite to the equal treatment of all persons within the realm if employers are placed in the position of adjudicating upon the requirements of their employees' religion. The issue in this instance, is not racial or religious discrimination: it is communalism.

- Speech in Walsall (9 February 1968), quoted in Still to Decide (Elliot Right Way Books, 1972), p. 292

- What I would take 'racialist' to mean is a person who believes in the inherent inferiority of one race of mankind to another, and who acts and speaks in that belief. So the answer to the question of whether I am a racialist is 'no'—unless, perhaps, it is to be a racialist in reverse. I regard many of the peoples in India as being superior in many respects—intellectually, for example, and in other respects—to Europeans. Perhaps that is over-correcting.

- Interview with the Birmingham Post (4 May 1968), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), pp. 466-467

- All government rests upon consent, and consent is not to be had without taking counsel with the most eminent or influential or representative of the governed, and seeking their advice: the act of taking counsel cannot be separated from the act of exercising authority. All government rests also upon habit, upon being exercised in the same way or a similar way to that in which the governed remember or believe that it was exercised before. Brute force can break with habit; but as soon as brute force begins to turn into government, it does so by starting to observe habitual modes of behaviour. Habitual forms or institutions for counsel and consent are thus of the essence of government.

- Introduction to his book The House of Lords in the Middle Ages (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1968), p. xi

- Too often today people are ready to tell us: "This is not possible, that is not possible." I say: whatever the true interest of our country calls for is always possible. We have nothing to fear but our own doubts.

- I hope those who shouted "Fascist" and "Nazi" are aware that before they were born I was fighting against Fascism and Nazism.

- Remarks to student hecklers at a speech in Cardiff (8 November 1968), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 489

- ...on such a matter it is the duty of a politician to make and to declare his judgement. I do so, I hope, not unduly moved – though why should I not be moved? – by the hundreds – no, thousands – of my countrymen who speak to me or write to me of their fear and foreboding: the old who rejoice that they will not live to see what is to come; the young who are determined that their children shall not grow up under the shadow of it. My judgement then is this: the people of England will not endure it. If so, it is idle to argue whether they ought to or ought not to. I do not believe it is in human nature that a country, and a country such as ours, should passively watch the transformation of whole areas which lie at the heart of it into alien territory.

- Speech to the annual conference of the Rotary Club in Eastbourne (16 November 1968), quoted in Reflections of a Statesman. The Writings and Speeches of Enoch Powell (London: Bellew, 1991), p. 390

- The West Indian or Asian does not, by being born in England, become an Englishman. In law he becomes a United Kingdom citizen by birth; in fact he is a West Indian or Asian still. Unless he be one of a small minority—for number, I repeat again and again, is of the essence—he will by the very nature of things have lost one country without gaining another, lost one nationality without acquiring a new one. Time is running against us and them. With the lapse of a generation or so we shall at last have succeeded – to the benefit of nobody – in reproducing ‘in England's green and pleasant land’ the haunting tragedy of the United States.

- Speech to the annual conference of the Rotary Club in Eastbourne (16 November 1968), quoted in Reflections of a Statesman. The Writings and Speeches of Enoch Powell (London: Bellew, 1991), p. 393

- It would be different if there were some great widespread public indignation and demand: "Away with the prescriptive upper house of Parliament". There is not. There was recently carried out by Mr. McKenzie and a colleague of his a survey of working-class political attitudes called Angels in Marble. They found that "only one-third of the entire working class sample, and only a slightly higher proportion of Labour voters, favoured abolishing the Lords or altering it in any way…About a third of the whole sample" of working-class voters in the country "see the Lords as an intrinsic part of the national tradition or of the government of the country." As so often, the ordinary rank and file of the electorate have seen a truth, an important fact, which has escaped so many more clever people—the underlying value of that which is traditional, of that which is prescriptive.

- Speech in the House of Commons (19 November 1968) regarding proposals for reforming the House of Lords.

- ...it depends indeed on whether the immigrants are different, and different in important respects from the existing population. Clearly, if they are identical, then no change for the good or bad can be brought about by the immigration. But if they are different, and to the extent that they are different, then numbers clearly are of the essence and this is not wholly – or mainly, necessarily – a matter of colour. For example, if the immigrants were Germans or Russians, their colour would be approximately the same as ours, but the problems which would be created and the change which could be brought about by a large introduction of a bloc of Germans or Russians into five areas in this country would be as serious – and in some respects more serious – than could follow from an introduction of a similar number of West Indians or Pakistanis.

- Any Questions?, BBC Radio (29 November 1968), from Reflections of a Statesman. The Writings and Speeches of Enoch Powell (London: Bellew, 1991), p. 395

- Enoch Powell: Now, we were invaded by the Danes, they did alter the country and we fought them for two hundred years. If that's what is meant – to be allowed to happen?

Marghanita Laski: Were we wise to do so? Didn't they add to us in the end? Wasn't there much more suffering and misery because we fought them?

Enoch Powell: Only because we fought them, and eventually subjugated them and Christianised them. (applause)- Any Questions?, BBC Radio (29 November 1968), from Reflections of a Statesman. The Writings and Speeches of Enoch Powell (London: Bellew, 1991), p. 396

- It depends on how you define the word "racialist." If you mean being conscious of the differences between men and nations, and from that, races, then we are all racialists. However, if you mean a man who despises a human being because he belongs to another race, or a man who believes that one race is inherently superior to another, then the answer is emphatically "No."

- Answer to David Frost, who asked him if he was a racialist (3 January 1969), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 504

- There is a limit to the number of (and I'm going to use this word in an entirely neutral sense) aliens who can be brought into a nation, particularly as close-knit and concentrated a nation as Britain is, without breaking the bounds of that society and setting up intolerable frictions and stresses as damaging to one side as to the other. Now, this is a question of number. But the relationship between number and difference is clearly important, because the more different they are – and colour is a signal, an outward signal of differences (not significant in itself, but it signalizes other differences that one can't deny) – the greater the difference, the smaller the numbers that can at any one time be accepted without breaking, or being thought to break (which comes to the same thing if we're talking about psychology), the framework of a nation and a society. So it's numbers.

- Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr.: The Trouble with Enoch (recorded 19 May 1969)

- They tell us we must be prepared to contemplate, in fact to welcome, the alteration and alienation of our towns and cities. They tell us there is no such thing as our own people and our country. Indeed there is, and I say it in no mean or arrogant or exclusive spirit. What I know is that we have an identity of our own, as we have a territory of our own, and that the instinct to preserve that identity, as to defend that territory, is one of the deepest and strongest implanted in mankind. I happen also to believe that the instinct is good and that its beneficent effects are not exhausted. ... In our time that identity has been threatened more than once. In the past it was threatened by violence and aggression from without. It is now threatened from within by the foreseeable consequences of a massive but unpremeditated and fortunately, in substantial measure, reversible immigration.

- Speech in Wolverhampton (8 June 1969), quoted in The Times (9 June 1969), p. 3

- Trevor Huddleston: ...what I still want to know from you, really, is why the presence of a coloured immigrant group is objectionable, when the presence of a non-coloured immigrant is not objectionable.

Enoch Powell: Oh no, oh no! On the contrary, I have often said that if we saw the prospect of five million Germans in this country at the end of the century, the risks of disruption and violence would probably be greater, and the antagonism which would be aroused would be more severe. The reason why the whole debate in this country on immigration is related to coloured immigration, is because there has been no net immigration of white Commonwealth citizens, and there could be no migration of aliens. This is merely an automatic consequence of the facts of the case; it is not because there is anything different, because there is anything necessarily more dangerous, about the alienness of a community from Asia, than about the alienness of a community from Turkey or from Germany, that we discuss this inevitably in terms of colour. It is because it is that problem.- The Great Debate, BBC TV (9 September 1969), from Reflections of a Statesman. The Writings and Speeches of Enoch Powell (London: Bellew, 1991), pp. 399-400

- Compassion is something individual and voluntary. You cannot compel somebody to be compassionate; nor can you be vicariously compassionate by compelling somebody else. The Good Samaritan would have lost all merit if a Roman soldier were standing by the road with a drawn sword, telling him to get on with it and look after the injured stranger. Because there can be no such thing as compulsory compassion or vicarious compassion, therefore it is a humbugging abuse of language, intended to deceive, to talk about a 'compassionate Government' or a 'compassionate party'—or even a 'compassionate society', unless one simply means by that a society which happens to contain a lot of compassionate individuals. Nor let anyone protest: 'Oh, but when I vote for a party which will "make provision on an unprecedented scale for those in need of help", it means I too shall have to pay my whack and so I am being compassionate after all'. Nonsense! The purpose of your vote is not to make yourself subscribe—that you can freely do at any time—but to compel others.

- Speech to the Harborough Division Conservative Association Gala, Leicester (27 September 1969), from Still to Decide (Elliot Right Way Books, 1972), pp. 22-23

1970s

- It is of the nature of all internecine violence that it lives on hope. Violence feeds upon the hope of success ... violence will not continue indefinitely where the objects which it proposes to itself appear to be unattainable, or at any rate unattainable within a predictable future. The Government in Northern Ireland and the Government in this country actually assist violence and strengthen it in so far as they appear to act and appear to reform under the pressure of violence... [The Government should ensure that] neither by word nor deed do we treat the membership of the Six Counties in the United Kingdom as negotiable. Every word or act which holds out the prospect that their unity with the rest of the United Kingdom might be negotiable is itself, consciously or unconsciously, a contributory cause to the continuation of violence in Northern Ireland.

- Speech in the House of Commons (7 April 1970)

- All that I will say is that in 1939 I voluntarily returned from Australia to this country to serve as a private soldier in the war against Germany and Nazism. I am the same man today... It does not follow that because a person resident in this country is not English that he does not enjoy equal treatment before the law and public authorities. I set my face like flint against discrimination.

- Reacting to Tony Benn's speech that "the flag hoisted at Wolverhampton [Powell's constituency] is beginning to look like the one that fluttered over Dachau and Belsen" (3 June 1970), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 556.

- Some of us personally witnessed what was done on the continent under that sign and it is a symbol we shall never forget.

- Reacting to a youth who had given the Hitler salute; from a speech in Wolverhampton (6 June 1970), quoted in Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 558.

- It so happens that I never talk about race. I do not know what race is.

- The Guardian (6 June 1970).

Have you ever wondered, perhaps, why opinions which the majority of people quite naturally hold are, if anyone dares express them publicly, denounced as 'controversial, 'extremist', 'explosive', 'disgraceful', and overwhelmed with a violence and venom quite unknown to debate on mere political issues? It is because the whole power of the aggressor depends upon preventing people from seeing what is happening and from saying what they see.

The most perfect, and the most dangerous, example of this process is the subject miscalled, and deliberately miscalled, 'race'. The people of this country are told that they must feel neither alarm nor objection to a West Indian, African and Asian population which will rise to several millions being introduced into this country. If they do, they are 'prejudiced', 'racialist'... A current situation, and a future prospect, which only a few years ago would have appeared to everyone not merely intolerable but frankly incredible, has to be represented as if welcomed by all rational and right-thinking people. The public are literally made to say that black is white. Newspapers like the Sunday Times denounce it as 'spouting the fantasies of racial purity' to say that a child born of English parents in Peking is not Chinese but English, or that a child born of Indian parents in Birmingham is not English but Indian. It is even heresy to assert the plain fact that the English are a white nation. Whether those who take part know it or not, this process of brainwashing by repetition of manifest absurdities is a sinister and deadly weapon. In the end, it renders the majority, who are marked down to be the victims of violence or revolution or tyranny, incapable of self-defence by depriving them of their wits and convincing them that what they thought was right is wrong. The process has already gone perilously far, when political parties at a general election dare not discuss a subject which results from and depends on political action and which for millions of electors transcends all others in importance; or when party leaders can be mesmerised into accepting from the enemy the slogans of 'racialist' and 'unChristian' and applying them to lifelong political colleagues...

In the universities, we are told that education and the discipline ought to be determined by the students, and that the representatives of the students ought effectively to manage the institutions. This is nonsense—manifest, arrant nonsense; but it is nonsense which it is already obligatory for academics and journalists, politicians and parties, to accept and mouth upon pain of verbal denunciation and physical duress.

We are told that the economic achievement of the Western countries has been at the expense of the rest of the world and has impoverished them, so that what are called the 'developed' countries owe a duty to hand over tax-produced 'aid' to the governments of the undeveloped countries. It is nonsense—manifest, arrant nonsense; but it is nonsense with which the people of the Western countries, clergy and laity, but clergy especially—have been so deluged and saturated that in the end they feel ashamed of what the brains and energy of Western mankind have done, and sink on their knees to apologise for being civilised and ask to be insulted and humiliated.

Then there is the 'civil rights' nonsense. In Ulster we are told that the deliberate destruction by fire and riot of areas of ordinary property is due to the dissatisfaction over allocation of council houses and opportunities for employment. It is nonsense—manifest, arrant nonsense; but that has not prevented the Parliament and government of the United Kingdom from undermining the morale of civil government in Northern Ireland by imputing to it the blame for anarchy and violence.

Most cynically of all, we are told, and told by bishops forsooth, that communist countries are the upholders of human rights and guardians of individual liberty, but that large numbers of people in this country would be outraged by the spectacle of cricket matches being played here against South Africans. It is nonsense—manifest, arrant nonsense; but that did not prevent a British Prime Minister and a British Home Secretary from adopting it as acknowledged fact.

- The "enemy within" speech during the 1970 general election campaign; speech to the Turves Green Girls School, Northfield, Birmingham (13 June 1970), from Still to Decide (Eliot Right Way Books, 1972), pp. 36-37.

- A single currency means a single government, and that single government would be the government whose policies determined every aspect of economic life.

- Speech in Tamworth (15 June 1970), from Simon Heffer, Like the Roman. The Life of Enoch Powell (Phoenix, 1999), p. 563.

- The question...of membership [of the EEC] resolves itself...into the most basic of all possible questions which can be addressed to the people of any nation: can they, and will they, so merge themselves with others that, in face of the external world, there is no longer ‘we’ and ‘they’, but only ‘we’; that the interests of the whole are instinctively seen as over-riding those of any part; that a single political will and authority, which must necessarily be that of the majority, is unconditionally accepted as binding upon us all? That is the question. That is what the real debate is about. ... For myself, I say that to me it is inconceivable that the people of this nation could or would so identify themselves politically with the peoples of the continent of Western Europe to form with them one entity and in effect one nation.

- Speech in Banbridge, County Down (16 January 1971), quoted in The Common Market: The Case Against (Elliot Right Way Books, 1971), p. 48

- ...we are talking about economic and political union. We are posing a question about political entity, about nationhood—the thing for which men, if necessary, fight and, if necessary, die, and to preserve which men think no sacrifice too great. In respect of our nationhood, then, I say that we are not a part of the continent of Europe. The whole development and nature of our national identity and consciousness has been not merely separate from that of the countries of the Continent of Europe but actually antithetical; and, with the centuries, so far from growing together, our institutions and outlook have rather grown apart from those of our neighbours on the continent. In our history, both recent and earlier, the principal events which have placed their stamp upon our consciousness of who we are, were the very moments in which we have been alone, confronting a Europe which was lost or hostile. That is the picture, that is the folk memory, by which our nation has been formed.

- Speech in the House of Commons (21 January 1971)

- Now, at present Britain has no V.A.T., and the questions whether this new tax should be introduced, how it should be levied, and what should be its scope, would be matters of debate in the country and in Parliament. The essence of parliamentary democracy lies in the power to debate and impose taxation: it is the vital principle of the British House of Commons, from which all other aspects of its sovereignty ultimately derive. With Britain in the community, one important element of taxation would be taken automatically, necessarily and permanently out of the hands of the House of Commons...Those matters which sovereign parliaments debate and decide must be debated and decided not by the British House of Commons but in some other place, and by some other body, and debated and decided once for the whole Community...it is a fact that the British Parliament and its paramount authority occupies a position in relation to the British nation which no other elective assembly in Europe possesses. Take parliament out of the history of England and that history itself becomes meaningless. Whole lifetimes of study cannot exhaust the reasons why this fact has come to be, but fact it is, so that the British nation could not imagine itself except with and through its parliament. Consequently the sovereignty of our parliament is something other for us than what your assemblies are for you. What is equally significant, your assemblies, unlike the British Parliament, are the creation of deliberate political acts, and most of recent political acts. The notion that a new sovereign body can be created is therefore as familiar to you as it is repugnant, not to say unimaginable, to us. This deliberate, and recent, creation of sovereign assemblies on the continent is in turn an aspect of the fact that the continent is familiar, and familiar in the recent past, with the creation of nation states themselves. Four of the six members of the Community came into existence as such no more than a century or a century and a half ago – within the memory of two lifetimes.

- Speech in Lyons (12 February 1971), from The Common Market: The Case Against (Elliot Right Way Books, 1971), pp. 65-68.

- An essential element in forming a single electorate is the sense that in the last resort all parts of it stand, or fall, survive or perish, together. This sense the British do not share with the inhabitants of the continent of Western Europe. Of all the nations of Europe Britain and Russia alone, though for opposite reasons, have this in common: they can be defeated in the decisive land battle and still survive. This characteristic Russia owes to her immensity. Britain owes it to her ditch. The British feel – and I believe that instinct corresponds with sound military reason – that the ditch is as significant in what we call the nuclear age as it proved to be in the air age and had been in the age of the Grande Armée of Napoleon or the Spanish infantry of Philip II. Error or truth, myth or reality, the belief itself is a habit of mind which has helped to form the national identity of the British and cannot be divorced from it.

- Speech in Lyons (12 February 1971), from The Common Market: The Case Against (Elliot Right Way Books, 1971), pp. 68-69.

- So long as the figures 'now superseded' and the academic projections based upon them held sway, it was possible for politicians to shrug their shoulders. With so much of immediate and indisputable importance on their hands, why should they attend to what was forecast for the end of the century, when most of them would be not only out of office but dead and gone? … It was not for them to heed the cries of anguish from those of their own people who already saw their towns being changed, their native places turned into foreign lands, and themselves displaced as if by a systematic colonisation. For these the much vaunted compassion of the parties and politicians was not available: the parties and the politicians preferred to be busy making speeches on race relations; and if any of their number dared to tell them the truth, even less than the whole truth, about what was happening and what would happen here in England, they denounced them as racialist and turned them out of doors. They could feel safe; for they said in their hearts: 'If trouble comes, it will not be in our time; let the next generation see to it!' … The explosive which will blow us asunder is there and the fuse is burning, but the fuse is shorter than had been supposed. The transformation which I referred to earlier as being without even a remote parallel in our history, the occupation of the hearts of this metropolis and of towns and cities across England by a coloured population amounting to millions, this before long will be past denying. It is possible that the people of this country will, with good or ill grace, accept what they did not ask for, did not want and were not told of. My own judgment—it is a judgment which the politician has a duty to form to the best of his ability—I have not feared to give: it is—to use words I used two years and a half ago—that 'the people of England will not endure it'.

- Speech to the Carshalton and Banstead Young Conservatives at Carshalton Hall (15 February 1971), from Still to Decide (Eliot Right Way Books, 1972), pp. 202-203.

One of the most dangerous words is 'extremist'. A person who commits acts of violence is not an 'extremist'; he is a criminal. If he commits those acts of violence with the object of detaching part of the territory of the United Kingdom and attaching it to a foreign country, he is an enemy under arms. There is the world of difference between a citizen who commits a crime, in the belief, however mistaken, that he is thereby helping to preserve the integrity of his country and his right to remain a subject of his sovereign, and a person, be he citizen or alien, who commits a crime with the intention of destroying that integrity and rendering impossible that allegiance. The former breaches the peace; the latter is executing an act of war. The use of the word 'extremist' of either or both conveys a dangerous untruth: it implies that both hold acceptable opinions and seek permissible ends, only that they carry them to 'extremes'. Not so: the one is a lawbreaker; the other is an enemy.

The same purpose, that of rendering friend and foe indistinguishable, is achieved by references to the 'impartiality' of the British troops and to their function as 'keeping the peace'. The British forces are in Northern Ireland because an avowed enemy is using force of arms to break down lawful authority in the province and thereby seize control. The army cannot be 'impartial' towards an enemy, nor between the aggressor and the aggressed: they are not glorified policemen, restraining two sets of citizens who might otherwise do one another harm, and duty bound to show no 'partiality' towards one lawbreaker rather than another. They are engaged in defeating an armed attack upon the state. Once again, the terminology is designed to obliterate the vital difference between friend and enemy, loyal and disloyal.

Then there are the 'no-go' areas which have existed for the past eighteen months. It would be incredible, if it had not actually happened, that for a year and a half there should be areas in the United Kingdom where the Queen's writ does not run and where the citizen is protected, if protected at all, by persons and powers unknown to the law. If these areas were described as what they are—namely, pockets of territory occupied by the enemy, as surely as if they had been captured and held by parachute troops—then perhaps it would be realised how preposterous is the situation. In fact the policy of refraining from the re-establishment of civil government in these areas is as wise as it would be to leave enemy posts undisturbed behind one's lines.

- Speech to the South Buckinghamshire Conservative Women's Annual Luncheon in Beaconsfield (19 March 1971), from Reflections of a Statesman. The Writings and Speeches of Enoch Powell (London: Bellew, 1991), pp. 487-488.

- ...when the empire dissolved...the people of Britain suffered from a kind of vertigo: they could not believe that they were standing upright, and reached out for something to clutch. It seemed axiomatic that economically, as well as politically, they must be part of something bigger, though the deduction was as unfounded as the premise. So some cried: 'Revive the Commonwealth'. And others cried: 'Let's go in with America into a North Atlantic Free Trade Area'. Yet others again cried: 'We have to go into Europe: there's no real alternative'. In a sense they were right: there is no alternative grouping. In a more important sense they were wrong: there is no need for joining anything. A Britain which is ready to exchange goods, services and capital as freely as it can with the rest of the world is neither isolated nor isolationist. It is not, in the sneering phrases of Chamberlain's day, 'Little England'...The Community is not a free trade area, which is what Britain, with a correct instinct, tried vainly to convert it into, or combine it into, in 1957-60. For long afterwards indeed many Britons continued to cherish the delusion that it really was a glorified free trade area and would turn out to be nothing more. On the contrary the Community is, what its name declares, a prospective economic unit. But an economic unit is not defined by economics – there are no natural economic units – it is defined by politics. What we call an economic unit is really a political unit viewed in its economic aspect: the unit is political.

- Speech in Frankfurt (29 March 1971), from The Common Market: The Case Against (Elliot Right Way Books, 1971), pp. 76-77.

- This is the positive aspect of British opposition to entry into the Community – the breadth and depth of the people's conviction that in no foreseeable future could they in this sense form one electorate with the inhabitants of the continent. ... It is that in their thousand-year history the British Isles has made a nation which recognizes itself more in its separation and difference from the continent than its similarity and kinship.

- Speech in Turin (4 May 1971), quoted in The Common Market: The Case Against (Elliot Right Way Books, 1971), pp. 95–96

- The prospect of a Russian conquest of Western Europe is one for which history affords no material. The theory that the Russians have not advanced from the Elbe to the Atlantic because of the nuclear deterrent is not more convincing than the theory that they have not done so because they do not want to do so and have never envisaged, unless perhaps in terms of world revolution, a Russian hegemony in Western Europe... Of all the nations of Europe, Britain and Russia are the only ones, though for opposite reasons, which have this thing in common: that they can be defeated in the decisive land battle and still survive. This characteristic, which Russia owes to her immensity, Britain owes to her moat.

- Speech to The Hague (17 May 1971), from The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), p. 97, p. 100.

- In the ultimate matter of life and death, survival or defeat, the insular position of the British nation has set us apart from the inhabitants of the adjacent continent. This is a political fact which cannot be pretended out of existence. As long as it remains true, or is believed by the British themselves to remain true, the commitment of Britain to any continental combination can never be total. ... True, it has often been rumoured that Britain had lost, or was about to lose, that characteristic; but events have hitherto always proved that she had it still, and those events are the most formative element in the folk-memory of the British people. ... This is the reason why Britain, which is in many sense as European as any nation, cannot be integrated politically with the European continent.

- Speech to The Hague (17 May 1971), quoted in The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), p. 109

- Opinion has been right to fasten upon sovereignty as the central issue. Either British entry is a declaration of intent to surrender this country's sovereignty, stage by stage, in all that matters as a nation, and makes a nation, or else it is an empty gesture, disgraceful in its hollowness alike to those who proffer and to whose who accept it. The superior people laugh at those who talk about losing our Queen and our Monarchy. ... The Queen is the Queen in Parliament, as truly today as when her predecessor, Tudor Henry, observed that ‘we are nowhere so high in our estate royal as in this Our High Court of Parliament’. The question which the people of this country will have proposed to them is: will you, or will you not, continue to be governed by the Queen in Parliament? It is no less than that, and they have understood it.

- Speech in Doncaster (19 June 1971), quoted in The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), p. 119

- In your town, in mine, in Wolverhampton, in Smethwick, in Birmingham, people see with their own eyes what they dread, the transformation during their own lifetime or, if they are already old, during their children's, of towns, cities and areas that they know into alien territory...Of the great multitude, numbering already two million, of West Indians and Asians in England, it is no more true to say that England is their country than it would be to say that the West Indies, or Pakistan, or India are our country. In these great numbers they are, and remain, alien here as we would be in Kingston or in Delhi; indeed, with the growth of concentrated numbers, the alienness grows, not by choice but by necessity. It is a human fact which good will, tolerance, comprehension and all the social virtues do not touch. The process is that of an invasion, not, of course, with the connotation either of violence or a premeditated campaign but in the sense that a people find themselves displaced in the only country that is theirs, by those who do have another country and whose home will continue to be elsewhere for successive generations.

- Speech to the Conservative Supper Club in Smethwick (8 September 1971), from Still to Decide (Eliot Right Way Books, 1972), pp. 189-190

- I do not believe that this nation, which has maintained and defended its independence for a thousand years, will now submit to see it merged or lost; nor did I become a member of our sovereign Parliament in order to consent to that sovereignty being abated or transferred. Come what may, I cannot and will not.

- Speech to the Conservative Party Conference in Brighton (13 October 1971), quoted in The Times (14 October 1971), p. 4

- Virtually the entire inflow was therefore Asiatic, and all but three or four thousand of that inflow originated from the Indian subcontinent... It is by 'black Power' that the headlines are caught, and under the shape of the negro that the consequences for Britain of immigration and what is miscalled 'race' are popularly depicted. Yet it is more truly when he looks into the eyes of Asia that the Englishman comes face to face with those who will dispute with him the possession of his native land.

- Speech to the Southall Chamber of Commerce, Centre Airport Hotel, Middlesex (4 November 1971), from Still to Decide (Eliot Right Way Books, 1972), p. 209

- The omnipotence of Parliament is for the British what for other nations is represented by the constitution, the declaration of independence and the law of human rights all rolled into one. That division of powers which was wrongly deduced from observation of Britain in the eighteenth century is unknown to Britain: just because we have no written constitution, the control of Parliament over both law and government has to be unlimited. In order for Britain to join the Community, the House of Commons has to be told, and to accept, that it will progressively lose its exclusive power to control legislation and government.

- Speech in Vaduz (15 January 1972), quoted in The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), pp. 30–31

- The relevant fact about the history of the British Isles and above all of England is its separateness in a political sense from the history of continental Europe. The English have never belonged to it and have always known that they did not belong. The assertion contains no element of paradox. The Angevin Empire contradicts it as little as the English claim to the throne of France; neither the possession of Gascony nor the inheritance of Hanover made Edward I or George III anything but English sovereigns. When Henry VIII declared that 'this realm of England is an empire (imperium) of itself', he was making not a new claim but a very old one; but he was making it at a very significant point of time. He meant—as Edward I had meant, when he said the same over two hundred years before—that there is an imperium on the continent, but that England is another imperium outside its orbit and is endowed with the plenitude of its own sovereignty. The moment at which Henry VIII repeated this assertion was that of what is misleadingly called 'the reformation'—misleadingly, because it was, and is, essentially a political and not a religious event. The whole subsequent history of Britain and the political character of the British people have taken their colour and trace their unique quality from that moment and that assertion. It was the final decision that no authority, no law, no court outside the realm would be recognised within the realm. When Cardinal Wolsey fell, the last attempt had failed to bring or keep the English nation within the ambit of any external jurisdiction or political power: since then no law has been made for England outside England, and no taxation has been levied in England by or for an authority outside England—or not at least until the proposition that Britain should accede to the Common Market.

- Speech to The Lions' Club, Brussels (24 January 1972), from The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), pp. 49-50

- [Parliament's] uniqueness lies in its virtually uninterrupted exercise of sovereignty through the centuries, so that, in the modern world of written constitutions and artificially erected representative assemblies, there is no other nation which is one with its parliament as we are. Among all the countries of Europe there is no other of which it could be said that its history would be unintelligible, almost non-existent, if the history of its parliament were removed.

- Speech to The Lions' Club, Brussels (24 January 1972), quoted in The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), pp. 50–51

- Such is, and will be seen to be, the effect of the legislation which the House of Commons must accept if the Treaty of Accession is to be ratified. It will be asked to divest itself of the unrestricted competence and authority which it has gained and maintained over centuries, and which the people of Britain regard as the guarantee of their national independence and political liberties.

- Speech to The Lions' Club, Brussels (24 January 1972), quoted in The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), pp. 52–53

- The Bill ... does manifest some of the major consequences. It shows first that it is an inherent consequence of accession to the Treaty of Rome that this House and Parliament will lose their legislative supremacy. It will no longer be true that law in this country is made only by or with the authority of Parliament... The second consequence ... is that this House loses its exclusive control—upon which its power and authority has been built over the centuries—over taxation and expenditure. In future, if we become part of the Community, moneys received in taxation from the citizens of this country will be spent otherwise than upon a vote of this House and without the opportunity ... to debate grievance and to call for an account of the way in which those moneys are to be spent. For the first time for centuries it will be true to say that the people of this country are not taxed only upon the authority of the House of Commons. The third consequence which is manifest on the face of the Bill, in Clause 3 among other places, is that the judicial independence of this country has to be given up. In future, if we join the Community, the citizens of this country will not only be subject to laws made elsewhere but the applicability of those laws to them will be adjudicated upon elsewhere; and the law made elsewhere and the adjudication elsewhere will override the law which is made here and the decisions of the courts of this realm.

- Speech in the House of Commons (17 February 1972) on the Second Reading of the European Communities Bill

- For this House, lacking the necessary authority either out-of-doors or indoors, legislatively to give away the independence and sovereignty of this House now and for the future is an unthinkable act. Even if there were not those outside to whom we have to render account, the very stones of this place would cry out against us if we dared such a thing. We are here acting not only collectively but as individuals; and each hon. Member takes his own responsibility upon himself—as I do, when I say for myself "It shall not pass".

- Speech in the House of Commons (17 February 1972) on the Second Reading of the European Communities Bill

- Make no mistake, the real power resides not where present authority is exercised but where it is expected that authority will in future be exercised. The magnetic attraction of power is exercised by the prospect long before the reality is achieved; and the trek towards the rising sun, which is already in progress in 1972, would swell to an exodus before long. What do you imagine is the reason why Roy Jenkins is prepared to resign the front bench and divide his party in the endeavour to give a Conservative Prime Minister a majority in the House of Commons? The motive is not ignoble or discreditable—I am not asserting that—but it is a motive which it behoves people in Britain well to understand. It is the ambition to exercise his talents on the stage of Europe and to participate in taking decisions not for Britain here at home but for Europe in Brussels, Paris, Luxembourg or wherever else the imperial pavilions may be pitched. He does not, I assure you, forsee his future triumphs and achievements where his predecessors have seen them in the past – at the despatch box in the House of Commons or in the Cabinet room at Downing St. These are not good enough: the vision splendid beckons elsewhere.

- Speech at Millom, Cumberland (29 April 1972), from A Nation or No Nation? Six Years in British Politics (Elliot Right Way Books, 1977), p. 42. Jenkins had resigned from the Shadow Cabinet and as deputy leader of the Labour Party due to Labour's opposition to British entry into the EEC. Jenkins wrote to Powell to claim what he said was "totally untrue". Four years later Jenkins would leave front line British politics to become President of the European Commission.

- The House of Commons is at this moment being asked to agree to the renunciation of its own independence and supreme authority—but not the House of Commons by itself. The House of Commons is the personification of the people of Britain: its independence is synonymous with their independence; its supremacy is synonymous with their self-government and freedom. Through the centuries Britain has created the House of Commons and the House of Commons has moulded Britain, until the history of the one and the life of the one cannot be separated from the history and life of the other. In no other nation in the world is there any comparable relationship. Let no one therefore allow himself to suppose that the life-and-death decision of the House of Commons is some private affair of some privileged institution which at intervals swims into his ken and out of it again. It is the life-and-death decision of Britain itself, as a free, independent and self-governing nation. For weeks, for months the battle on the floor of the House of Commons will swing backwards and forwards, through interminable hours of debates and procedures and votes in the division lobbies; and sure enough the enemies and despisers of the House of Commons will represent it all as some esoteric game or charade which means nothing for the outside world. Do not be deceived. With other weapons and in other ways the contention is as surely about the future of Britain's nationhood as were the combats which raged in the skies over southern England in the autumn of 1940. The gladiators are few; their weapons are but words; and yet the fight is everyman's.

- Speech at Newton, Montgomeryshire (4 March 1972), from The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), pp. 57-8

- When German sovereigns acceded to the throne of Britain, they were astonished to discover what George II used to call ‘that damned House of Commons’; but they learnt the lesson that the House of Commons had its way in the end. In former times and in modern times there has been a procession of occasions when the nations of the continent forgot or ignored the House of Commons to their cost, because to forget or ignore the people of Britain themselves, who, however late they awaken, will not suffer themselves to be parted from their heritage of parliamentary self-government and national independence.

- Speech at Newton, Montgomeryshire (4 March 1972), quoted in The Common Market: Renegotiate or Come Out (Elliot Right Way Books, 1973), p. 59