Emily Jane Brontë (30 July 1818 – 19 December 1848), one of the Brontë sisters, was an English novelist and poet, sister of Charlotte and Anne Brontë. She is most famous for her only novel, Wuthering Heights. She wrote under the pen name Ellis Bell.

Quotes

I Am the Only Being (1836)

No tongue would ask no eye would mourn...

- I am the only being whose doom

No tongue would ask no eye would mourn

I never caused a thought of gloom

A smile of joy since I was born

In secret pleasure — secret tears

This changeful life has slipped away

As friendless after eighteen years

As lone as on my natal day

- First melted off the hope of youth

Then Fancy's rainbow fast withdrew

And then experience told me truth

In mortal bosoms never grew

'Twas grief enough to think mankind

All hollow servile insincere

But worse to trust to my own mind

And find the same corruption there

Spellbound (November 1837)

.jpg)

The wild winds coldly blow;

But a tyrant spell has bound me

And I cannot, cannot go.

The night is darkening round me,

The wild winds coldly blow;

But a tyrant spell has bound me

And I cannot, cannot go.The giant trees are bending

Their bare boughs weighed with snow,

And the storm is fast descending,

And yet I cannot go.Clouds beyond clouds above me,

Wastes beyond wastes below;

But nothing drear can move me—

I will not, cannot go.

Shall Earth No More Inspire Thee (May 1841)

- Shall Earth no more inspire thee,

Thou lonely dreamer now?

Since passion may not fire thee

Shall Nature cease to bow?

Thy mind is ever moving

In regions dark to thee;

Recall its useless roving —

Come back and dwell with me —

The Prisoner (October 1845)

- He comes with western winds, with evening's wandering airs,

With that clear dusk of heaven that brings the thickest stars;

Winds take a pensive tone and stars a tender fire

And visions rise and change which kill me with desire.

But first a hush of peace, a soundless calm descends;

The struggle of distress and fierce impatience ends

Mute music sooths my breast — unuttered harmony

That I could never dream till earth was lost to me.Then dawns the Invisible; the Unseen its truth reveals;

My outward sense is gone, my inward essence feels —

Its wings are almost free, its home, its harbour found;

Measuring the gulf, it stoops and dares the final bound —O, dreadful is the check — intense the agony

When the ear begins to hear and the eye begins to see;

When the pulse begins to throb, the brain to think again,

The soul to feel the flesh and the flesh to feel the chain.Yet I would lose no sting, would wish no torture less;

The more that anguish racks the earlier it will bless;

And robed in fires of Hell, or bright with heavenly shine

If it but herald Death, the vision is divine —

What Use Is It To Slumber Here?

May promise a brighter morrow.

- What use is it to slumber here:

Though the heart be sad and weary?

What use is it to slumber here

Though the day rise dark and dreary?

- For that mist may break when the sun is high

And this soul forget its sorrow

And the rose ray of the closing day

May promise a brighter morrow.

Love and Friendship

But which will bloom most constantly?

- Love is like the wild rose-briar;

Friendship like the holly-tree.

The holly is dark when the rose-briar blooms,

But which will bloom most constantly?

A Little While, a Little While (1846)

- Still, as I mused, the naked room,

The alien firelight died away;

And from the midst of cheerless gloom

I passed to bright, unclouded day.- Stanza vi.

- A heaven so clear, an earth so calm,

So sweet, so soft, so hushed an air;

And, deepening still the dreamlike charm,

Wild moor-sheep feeding everywhere.- Stanza vii.

To Imagination (1846)

- When weary with the long day's care,

And earthly change from pain to pain,

And lost and ready to despair,

Thy kind voice calls me back again:

Oh, my true friend! I am not lone,

While thou canst speak with such a tone!

- So hopeless is the world without;

The world within I doubly prize;

Thy world, where guile, and hate, and doubt,

And cold suspicion never rise;

Where thou, and I, and Liberty,

Have undisputed sovereignty.

- What matters it, that, all around,

Danger, and guilt, and darkness lie,

If but within our bosom's bound

We hold a bright, untroubled sky,

Warm with ten thousand mingled rays

Of suns that know no winter days?

- Reason, indeed, may oft complain

For Nature's sad reality,

And tell the suffering heart, how vain

Its cherished dreams must always be;

And Truth may rudely trample down

The flowers of Fancy, newly-blown:

- But, thou art ever there, to bring

The hovering vision back, and breathe

New glories o'er the blighted spring,

And call a lovelier Life from Death,

And whisper, with a voice divine,

Of real worlds, as bright as thine.

- I trust not to thy phantom bliss,

Yet, still, in evening's quiet hour,

With never-failing thankfulness,

I welcome thee, Benignant Power;

Sure solacer of human cares,

And sweeter hope, when hope despairs!

Remembrance (1846)

- Cold in the earth—and the deep snow piled above thee,

Far, far, removed, cold in the dreary grave!

Have I forgot, my only Love, to love thee,

Severed at last by Time's all-severing wave?

- Sweet Love of youth, forgive, if I forget thee,

While the world's tide is bearing me along;

Other desires and other hopes beset me,

Hopes which obscure, but cannot do thee wrong!

- But when the days of golden dreams had perished,

And even Despair was powerless to destroy;

Then did I learn how existence could be cherished,

Strengthened, and fed without the aid of joy.

Faith and Despondency (1846)

- The winter wind is loud and wild,

Come close to me, my darling child;

Forsake thy books, and mateless play;

And, while the night is gathering grey,

We'll talk its pensive hours away;—

No Coward Soul Is Mine (1846)

Nor atom that his might could render void:

Thou — Thou art Being and Breath,

And what Thou art may never be destroyed.

- Despite Charlotte's claim, it is not the last Emily's poem Full text at Wikisource

No coward soul is mine,

No trembler in the world's storm-troubled sphere:

I see Heaven's glories shine,

And Faith shines equal, arming me from Fear.O God within my breast,

Almighty, ever-present Deity!

Life — that in me has rest,

As I — undying Life — have power in Thee!Vain are the thousand creeds

That move men's hearts: unutterably vain;

Worthless as withered weeds,

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main...

With wide-embracing love

Thy Spirit animates eternal years,

Pervades and broods above,

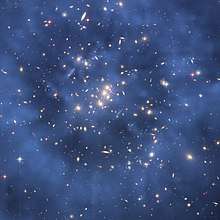

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates, and rears.Though earth and moon were gone,

And suns and universes ceased to be,

And Thou wert left alone,

Every existence would exist in Thee.There is not room for Death,

Nor atom that his might could render void:

Thou — Thou art Being and Breath,

And what Thou art may never be destroyed.

The Old Stoic (1846)

- Yes, as my swift days near their goal

'Tis all that I implore

In life and death a chainless soul

With courage to endure

Wuthering Heights (1847)

.jpg)

- "Wuthering" being a significant provincial adjective, descriptive of the atmospheric tumult to which its station is exposed in stormy weather. Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there at all times, indeed: one may guess the power of the north wind blowing over the edge, by the excessive slant of a few stunted firs at the end of the house; and by a range of gaunt thorns all stretching their limbs one way, as if craving alms of the sun.

- Mr. Lockwood (Ch. I).

- No, I’m running on too fast: I bestow my own attributes over-liberally on him.

- Mr. Lockwood on Heathcliff (Ch. I).

- Her position before was sheltered from the light: now, I had a distinct view of her whole figure and countenance. She was slender, and apparently scarcely past girlhood: an admirable form, and the most exquisite little face that I have ever had the pleasure of beholding: small features, very fair; flaxen ringlets, or rather golden, hanging loose on her delicate neck; and eyes — had they been agreeable in expression, they would have been irresistible.

- Mr. Lockwood on Catherine Linton (Ch. II).

- No, reprobate! You are a castaway - be off, or I'll hurt you seriously! I'll have you all modeled in wax and clay; and the first who passes the limits I fix, shall — I'll not say what he shall be done to — but, you'll see! Go, I'm looking at you!

- Catherine Linton to Joseph (Ch. III).

- As it spoke I discerned, obscurely, a child's face looking through the window. Terror made me cruel; and finding it useless to attempt shaking the creature off, I pulled its wrist on to the broken pane, and rubbed it to and fro till the blood ran down and soaked the bed-clothes: still it wailed, "Let me in!", and maintained its tenacious grip, almost maddening me with fear.

- Mr. Lockwood (Ch. III).

- I am now quite cured of seeking pleasure in society, be it country or town. A sensible man ought to find sufficient company in himself.

- Mr. Lockwood (Ch. III).

- What vain weathercocks we are! I, who had determined to hold myself independent of all social intercourse, and thanked my stars that at length I had lighted on a spot where it was next to impracticable. I, weak wretch, after maintaining till dusk a struggle with low spirits and solitude, was finally compelled to strike my colours; and under pretence of gaining information concerning the necessities of my establishment, I desired Mrs. Dean.

- Mr. Lockwood (Ch. IV).

- Rough as a saw-edge, and hard as whinstone! The less you meddle with him the better.

- Nelly Dean on Heathcliff (Ch. IV).

- He was, and is yet most likely, the wearisomest self-righteous Pharisee that ever ransacked a Bible to rake the promises to himself and fling the curses to his neighbours.

- Nelly Dean on Joseph (Ch. V).

- Instead of a wild, hatless little savage jumping into the house, and rushing to squeeze us all breathless, there lighted from a handsome black pony a very dignified person with brown ringlets falling from the cover of a feathered beaver, and a long cloth habit which she was obliged to hold up with both hands that she might sail in.

- Nelly Dean on Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. VII).

- Proud people breed sad sorrows for themselves.

- Nelly Dean (Ch. VII).

- "A good heart will help you to a bonny face, my lad", I continued, "if you were a regular black, and a bad one will turn the bonniest into something worse than ugly."

- Nelly Dean (Ch. VII).

- A person who has not done one half his day's work by ten o'clock runs a chance of leaving the other half undone.

- Nelly Dean (Ch. VII).

- I went to hide little Hareton, and to take the shot out of the master’s fowling-piece, which he was fond of playing with in his insane excitement, to the hazard of the lives of any who provoked, or even attracted his notice too much; and I had hit upon the plan of removing it, that he might do less mischief if he did go the length of firing the gun.

- Nelly Dean (Ch. VIII).

- I've dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas; they've gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the colour of my mind.

- Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. IX).

- 'I was only going to say that heaven did not seem to be my home; and I broke my heart with weeping to come back to earth; and the angels were so angry that they flung me out into the middle of the heath on the top of Wuthering Heights; where I woke sobbing for joy. That will do to explain my secret, as well as the other. I've no more business to marry Edgar Linton than I have to be in heaven; and if the wicked man in there had not brought Heathcliff so low I shouldn't have thought of it. It would degrade me to marry Heathcliff now; so he shall never know how I love him; and that not because he's handsome, Nelly, but because he's more myself than I am. Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same, and Linton's is as different as a moonbeam from lightning, or frost from fire.

- Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. IX).

- I can not express it; but surely you and everybody have a notion that there is, or should be an existence of yours beyond you. What were the use of creation if I were entirely contained here? My great miseries in this world have been Heathcliff's miseries, and I watched and felt each from the beginning; my great thought in living is himself. If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger. I should not seem a part of it. My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I'm well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff - he's always, always in my mind - not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself - but as my own being; so, don't talk of our separation again - it is impracticable.

- Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. IX).

- She seemed almost over fond of Mr. Linton; and even to his sister she showed plenty of affection. They were both very attentive to her comfort, certainly. It was not the thorn bending to the honeysuckles, but the honeysuckles embracing the thorn.

- Nelly Dean (Ch. X).

- On a mellow evening in September, I was coming from the garden with a heavy basket of apples which I had been gathering. It had got dusk, and the moon looked over the high wall of the court, causing undefined shadows to lurk in the corners of the numerous projecting portions of the building. I set my burden on the house steps by the kitchen door, and lingered to rest, and draw in a few more breaths of the soft, sweet air; my eyes were on the moon, and my back to the entrance, when I heard a voice behind me say —

- Nelly Dean (Ch. X).

- I heard of your marriage, Cathy, not long since; and, while waiting in the yard below, I meditated this plan — just to have one glimpse of your face — a stare of surprise, perhaps, and pretended pleasure; afterward settle my score with Hindley; and then prevent the law by doing execution on myself. Your welcome has put these ideas out of my mind; but beware of meeting me with another aspect next time!

- Heathcliff (Ch. X).

- I have such faith in Linton's love that I believe I might kill him, and he wouldn't wish to retaliate.

- Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. X).

- You are worse than twenty foes, you poisonous friend!

- Isabella Linton to Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. X).

- The tyrant grinds down his slaves and they don't turn against him, they crush those beneath them.

- Heathcliff (Ch. XI).

- You are welcome to torture me to death for your amusement; only allow me to amuse myself a little in the same style. And refrain from insult as much as you are able. Having levelled my palace, don't erect a hovel and complacently admire your own charity in giving me that for a home. If I imagined you really wished me to marry Isabel, I'd cut my throat!

- Heathcliff (Ch. XI).

- "Cathy, this lamb of yours threatens like a bull!" he said. "It is in danger of splitting its skull against my knuckles. By God, Mr. Linton, I'm mortally sorry that you are not worth knocking down!"

- Heathcliff (Ch. XI).

- "If I were only sure it would kill him," she interrupted, "I’d kill myself directly! These three awful nights, I’ve never closed my lids — and oh, I’ve been tormented! I’ve been haunted, Nelly! But I begin to fancy you don’t like me. How strange! I thought, though everybody hated and despised each other, they could not avoid loving me."

- Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. XII).

- Oh, I'm burning! I wish I were out of doors. I wish I were a girl again, half savage and hardy, and free, and laughing at injuries, not maddening under them! Why am I so changed?

- Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. XII).

- I assure you, a tiger, or a venomous serpent could not rouse terror in me equal to that which he wakens.

- Isabella Linton on Heathcliff (Ch. XIII).

- Any relic of the dead is precious, if they were valued living.

- Nelly Dean (Ch. XIII).

- Should there be danger of such an event — should he be the cause of adding a single more trouble to her existence — why, I think I shall be justified in going to extremes! I wish you had sincerity enough to tell me whether Catherine would suffer greatly from his loss. The fear that she would restrains me: and there you see the distinction between our feelings. Had he been in my place, and I in his, though I hated him with a hatred that turned my life to gall, I never would have raised a hand against him. You may look incredulous, if you please! I never would have banished him from her society, as long as she desired his. The moment her regard ceased, I would have torn his heart out and drank his blood! But till then, if you don't believe me, you don't know me — till then, I would have died by inches before I touched a single hair of his head!

- Heathcliff (Ch. XIV).

- I was a fool to fancy for a moment that she valued Edgar Linton's attachment more than mine; if he loved with all the powers of his puny being, he couldn't love as much in eighty years as I could in a day. And Catherine has a heart as deep as I have; the sea could be as readily contained in that house-trough as her whole affection be monopolized by him. Tush! He is scarcely a degree dearer to her than her dog, or her horse. It is not in him to be loved like me; how can she love in him what he has not?

- Heathcliff (Ch. XIV).

- I have no pity! I have no pity! The more the worms writhe, the more I yearn to crush out their entrails! It is a moral teething; and I grind with greater energy in proportion to the increase of pain.

- Heathcliff (Ch. XIV).

- You talk of her mind being unsettled - how the devil could it be otherwise, in her frightful isolation? And that insipid, paltry creature attending her from duty and humanity! From pity and charity. He might as well plant an oak in a flower-pot, and expect it to thrive, as imagine he can restore her to vigour in the soil of his shallow cares!

- Heathcliff (Ch. XIV).

- I shouldn’t care what you suffered. I care nothing for your sufferings. Why shouldn’t you suffer? I do! Will you forget me — will you be happy when I am in the earth? Will you say, twenty years hence, “That’s the grave of Catherine Earnshaw. I loved her long ago, and was wretched to lose her; but it is past. I’ve loved many others since — my children are dearer to me than she was, and, at death, I shall not rejoice that I am going to her, I shall be sorry that I must leave them!” Will you say so, Heathcliff?

- Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. XV).

- The thing that irks me most is this shattered prison, after all. I’m tired, tired of being enclosed here. I’m wearying to escape into that glorious world, and to be always there; not seeing it dimly through tears, and yearning for it through the walls of an aching heart; but really with it, and in it.

- Catherine Earnshaw (Ch. XV).

- Catherine Earnshaw, may you not rest as long as I am living! You said I killed you — haunt me then! The murdered do haunt their murderers, I believe; I know that ghosts have wandered on earth. Be with me always — take any form — drive me mad! Only do not leave me in this abyss where I can not find you! Oh, God! it is unutterable! I can not live without my life! I can not live without my soul!

- Heathcliff (Ch. XVI).

- Yesterday, you know, Mr. Earnshaw should have been at the funeral. He kept himself sober for the purpose - tolerably sober; not going to bed mad at six o'clock, and getting up drunk at twelve. Consequently he rose, in suicidal low spirits; as fit for the church as for a dance; and instead, he sat down by the fire and swallowed gin or brandy by tumblerfuls.

- Isabella Linton (Ch. XVII).

- I’d be glad of a retaliation that wouldn’t recoil on myself; but treachery and violence are spears pointed at both ends; they wound those who resort to them worse than their enemies.

- Isabella Linton (Ch. XVII).

- Oh, if God would but give me strength to strangle him in my last agony, I’d go to hell with joy.

- Hindley Earnshaw (Ch. XVII).

- The boy was fully occupied with his own cogitations for the remainder of the ride, till we halted before the farmhouse garden gate. I watched to catch his impressions in his countenance. He surveyed the carved front and low-browed lattices, the straggling gooseberry bushes, and crooked firs, with solemn intentness, and then shook his head; his private feelings entirely disapproved of the exterior of his new abode. But he had sense to postpone complaining — there might be compensation within.

- Nelly Dean (Ch. XX).

- Don't you think Hindley would be proud of his son, if he could see him? Almost as proud as I am of mine. But there's this difference, one is gold put to the use of paving stones; and the other is tin polished to ape a service of silver. Mine has nothing valuable about it; yet I shall have the merit of making it go as far as such poor stuff can go. His had first-rate qualities, and they are lost — rendered worse than unavailing.

- Heathcliff (Ch. XXI).

- My cousin fancies you are an idiot. There you experience the consequence of scorning "book larning," as you would say. Have you noticed, Catherine, his frightful Yorkshire pronunciation?

- Linton Heathcliff to Hareton Earnshaw (Ch. XXI).

- If thou weren't more a lass than a lad, I'd fell thee this minute, I would; pitiful lath of a crater!

- Hareton Earnshaw to Linton Heathcliff (Ch. XXI).

- The worst tempered bit of a sickly slip that ever struggled into its teens! Happily, as Mr. Heathcliff conjectured, he'll not win twenty! I doubt whether he'll see spring indeed — and small loss to his family, whenever he drops off; and lucky it is for us that his father took him. The kinder he was treated, the more tedious and selfish he'd be! I'm glad you have no chance of having him for a husband, Miss Catherine!

- Nelly Dean on Linton Heathcliff (Ch. XXIII).

- One time, however, we were near quarrelling. He said the pleasantest manner of spending a hot July day was lying from morning till evening on a bank of heath in the middle of the moors, with the bees humming dreamily about among the bloom, and the larks singing high up overhead, and the blue sky and bright sun shining steadily and cloudlessly. That was his most perfect idea of heaven's happiness — mine was rocking in a rustling green tree, with a west wind blowing, and bright white clouds flitting rapidly above; and not only larks, but throstles, and blackbirds, and linnets, and cuckoos pouring out music on every side, and the moors seen at a distance, broken into cool dusky dells; but close by great swells of long grass undulating in waves to the breeze; and woods and sounding water, and the whole world awake and wild with joy. He wanted all to lie in an ecstasy of peace; I wanted all to sparkle and dance in a glorious jubilee. I said his heaven would be only half alive, and he said mine would be drunk; I said I should fall asleep in his, and he said he could not breathe in mine.

- Catherine Linton (Ch. XXIV).

- He's such a cobweb, a pinch would annihilate him.

- Heathcliff on Linton Heathcliff (Ch. XXIX).

- His brightening mind brightened his features, and added spirit and nobility to their aspect.

- Nelly Dean on Hareton (Ch. XXXIII).

- I get levers and mattocks to demolish the two houses, and train myself to be capable of working like Hercules, and when every thing is ready and in my power, I find the will to lift a slate off either roof has vanished! My old enemies have not beaten me — now would be the precise time to revenge myself on their representatives. I could do it, and none could hinder me; but where is the use? I don't care for striking — I can't take the trouble to raise my hand! That sounds as if I had been labouring the whole time only to exhibit a fine trait of magnanimity. It is far from being the case. I have lost the faculty of enjoying their destruction, and I am too idle to destroy for nothing.

- Heathcliff (Ch. XXXIII).

- I have neither a fear, nor a presentiment, nor a hope of death. Why should I? With my hard constitution, and temperate mode of living, and unperilous occupations, I ought to, and probably shall remain above ground, till there is scarcely a black hair on my head. And yet I cannot continue in this condition! I have to remind myself to breathe — almost to remind my heart to beat! And it is like bending back a stiff spring — it is by compulsion that I do the slightest act, not prompted by one thought; and by compulsion that I notice anything alive or dead, which is not associated with one universal idea. I have a single wish, and my whole being and faculties are yearning to attain it. They have yearned towards it so long and so unwaveringly, that I’m convinced it will be reached — and soon — because it has devoured my existence. I am swallowed up in the anticipation of its fulfilment. My confessions have not relieved me — but they may account for some otherwise unaccountable phases of humour which I show. Oh, God! It's a long fight, I wish it were over!

- Heathcliff (Ch. XXXIII).

- I've done no injustice, and I repent of nothing. I'm too happy, and yet I'm not happy enough. My soul's bliss kills my body, but does not satisfy itself.

- Heathcliff (Ch. XXXIV).

- "They are afraid of nothing," I grumbled, watching their approach through the window. "Together they would brave Satan and all his legions."

- Mr. Lockwood (Ch. XXXIV).

My walk home was lengthened by a diversion in the direction of the kirk. When beneath its walls, I perceived decay had made progress, even in seven months - many a window showed black gaps deprived of glass; and slates jutted off, here and there, beyond the right line of the roof, to be gradually worked off in coming autumn storms.

I sought, and soon discovered, the three head-stones on the slope next the moor - the middle one, gray, and half buried in heath - Edgar Linton's only harmonized by the turf and moss, creeping up its foot - Heathcliff's still bare.

I lingered round them, under that benign sky; watched the moths fluttering among the heath and harebells; listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass; and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth.

- Mr. Lockwood (Ch. XXXIV). (Closing lines).

Quotes about Brontë

- Emily is not very fond of teaching but she would nevertheless take care of the housekeeping, and though she is rather withdrawn she has too kind a heart not to do her utmost for the well-being of the children — she is also very generous soul...

- Charlotte Brontë, in a letter to Constantin Heger (24 July 1844)

- My sister's [Emily's] disposition was not naturally gregarious; circumstances favoured and fostered her tendency to seclusion; except to go to church or take a walk on the hills, she rarely crossed the threshold of home. Though her feeling for the people round was benevolent, intercourse with them she never sought; nor, with very few exceptions, ever experienced. And yet she know them: knew their ways, their language, their family histories; she could hear of them with interest, and talk of them with detail, minute, graphic, and accurate; but WITH them, she rarely exchanged a word.

- Charlotte Brontë, Editor's Preface to the Second Edition of Wuthering Heights (1850).

- Emily Bronte was a wild, original, and striking creature, but her one book is a kind of prose Kubla Khan, — a nightmare of the superheated imagination.

- Frederic Harrison, Early Victorian literature (1895), p. 150.

- She should have been a man – a great navigator. Her powerful reason would have deduced new spheres of discovery from the knowledge of the old; and her strong imperious will would never have been daunted by opposition or difficulty, never have given way but with life. She had a head for logic, and a capability of argument unusual in a man and rarer indeed in a woman... impairing this gift was her stubborn tenacity of will which rendered her obtuse to all reasoning where her own wishes, or her own sense of right, was concerned.

- Constantin Héger, (Emily's teacher in Brussels in 1842,) in a letter to Mrs. Gaskell, as quoted in The Oxford History of the Novel in English, Vol. III (2011), p. 208.

- What is said of Charlotte may, with almost equal truth, be said of Emily and Anne; though they differed greatly in many points of character and disposition, they were each and all on common ground if a principle had to be maintained or a sham to be detected. They were all jealous of anything hollow or unreal. All were resolutely single-minded, eminently courageous, eminently simple in their habits, and eminently tender-hearted.

- Ellen Nussey, Reminiscences of Charlotte Brontë (1871)

- Emily Brontë had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte's, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes – kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you; she was too reserved. Their colour might be said to be dark grey, at other times dark blue, they varied so. She talked very little. She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.

- Ellen Nussey, Reminiscences of Charlotte Brontë (1871)

- The character of Emily Brontë was a peculiar mixture of timidity and Spartan-like courage. She was painfully shy, but physically she was brave to a surprising degree. She loved few persons, but those few with a passion of self-sacrificing tenderness and devotion. To other people's failings she was lenient and forgiving, but over herself she kept a continual and most austere watch, never allowing herself to deviate for one instant from what she considered her duty. She fought with her weakness to the very last, keeping up, and, marvellous to relate, about her accustomed duties in the house; and refusing strenuously to admit that anything ailed her, or to see a doctor. Her inflexibility of purpose was more like that of a strong man than of a delicate, weak woman...

- Eva Hope, Queens of Literature of the Victorian Era (1886), p. 168.

- Miss Emily était beaucoup moins brillante que sa sœur mais bien plus sympathique.

- Miss Emily was considerably less brilliant than her sister [Charlotte] but much more sympathetic.

- Louise de Bassompierre, Emily's fellow student in Brussels, Two Brussels Schoolfellows of Charlotte Brontë Brontë Society Transactions, 5:23 (1913)

- Wuthering Heights is a more difficult book to understand than Jane Eyre, because Emily was a greater poet than Charlotte. When Charlotte wrote she said with eloquence and splendour and passion “I love”, “I hate”, “I suffer”. Her experience, though more intense, is on a level with our own. But there is no “I” in Wuthering Heights. There are no governesses. There are no employers. There is love, but it is not the love of men and women. Emily was inspired by some more general conception. The impulse which urged her to create was not her own suffering or her own injuries. She looked out upon a world cleft into gigantic disorder and felt within her the power to unite it in a book. That gigantic ambition is to be felt throughout the novel — a struggle, half thwarted but of superb conviction, to say something through the mouths of her characters which is not merely “I love” or “I hate”, but “we, the whole human race” and “you, the eternal powers . . . ” the sentence remains unfinished. It is not strange that it should be so; rather it is astonishing that she can make us feel what she had it in her to say at all. It surges up in the half-articulate words of Catherine Earnshaw, “If all else perished and HE remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger; I should not seem part of it”. It breaks out again in the presence of the dead. “I see a repose that neither earth nor hell can break, and I feel an assurance of the endless and shadowless hereafter — the eternity they have entered — where life is boundless in its duration, and love in its sympathy and joy in its fulness.” It is this suggestion of power underlying the apparitions of human nature and lifting them up into the presence of greatness that gives the book its huge stature among other novels. But it was not enough for Emily Brontë to write a few lyrics, to utter a cry, to express a creed. In her poems she did this once and for all, and her poems will perhaps outlast her novel. But she was novelist as well as poet. She must take upon herself a more laborious and a more ungrateful task. She must face the fact of other existences, grapple with the mechanism of external things, build up, in recognisable shape, farms and houses and report the speeches of men and women who existed independently of herself. And so we reach these summits of emotion not by rant or rhapsody but by hearing a girl sing old songs to herself as she rocks in the branches of a tree; by watching the moor sheep crop the turf; by listening to the soft wind breathing through the grass. The life at the farm with all its absurdities and its improbability is laid open to us. We are given every opportunity of comparing Wuthering Heights with a real farm and Heathcliff with a real man. How, we are allowed to ask, can there be truth or insight or the finer shades of emotion in men and women who so little resemble what we have seen ourselves? But even as we ask it we see in Heathcliff the brother that a sister of genius might have seen; he is impossible we say, but nevertheless no boy in literature has a more vivid existence than his. So it is with the two Catherines; never could women feel as they do or act in their manner, we say. All the same, they are the most lovable women in English fiction. It is as if she could tear up all that we know human beings by, and fill these unrecognisable transparences with such a gust of life that they transcend reality. Hers, then, is the rarest of all powers. She could free life from its dependence on facts; with a few touches indicate the spirit of a face so that it needs no body; by speaking of the moor make the wind blow and the thunder roar.

- Virginia Woolf, in "Jane Eyre" And "Wuthering Heights" in The Common Reader (1916).

- So very little is known of Emily Brontë that every little detail awakens an interest. Her extreme reserve seemed impenetrable, yet she was intensely lovable; she invited confidence in her moral power. Few people have the gift of looking and smiling as she could look and smile. One of her rare expressive looks was something to remember through life, there was such a depth of soul and feeling, and yet a shyness of revealing herself—a strength of self-containment seen in no other. She was in the strictest sense a law unto herself, and a heroine in keeping to her law. She and gentle Anne were to be seen twined together as united statues of power and humility. They were to be seen with their arms lacing each other in their younger days whenever their occupations permitted their Union. On the top of a moor or in a deep glen Emily was a child in spirit for glee and enjoyment; or when thrown entirely on her own resources to do a kindness, she could be vivacious in conversation and enjoy giving pleasure. A spell of mischief also lurked in her on occasions when out on the moors. She enjoyed leading Charlotte where she would not dare to go of her own free-will. Charlotte had a mortal dread of unknown animals, and it was Emily’s pleasure to lead her into close vicinity, and then to tell her of how and of what she had done, laughing at her horror with great amusement. If Emily wanted a book she might have left in the sitting-room she would dart in again without looking at any one, especially if any guest were present. Among the curates, Mr. Weightman was her only exception for any conventional courtesy. The ability with which she took up music was amazing; the style, the touch, and the expression was that of a professor absorbed heart and soul in his theme. The two dogs, Keeper and Flossy, were always in quiet waiting by the side of Emily and Anne during their breakfast of Scotch oatmeal and milk, and always had a share handed down to them at the close of the meal. Poor old Keeper, Emily’s faithful friend and worshipper, seemed to understand her like a human being. One evening, when the four friends were sitting closely round the fire in the sitting-room, Keeper forced himself in between Charlotte and Emily and mounted himself on Emily’s lap; finding the space too limited for his comfort he pressed himself forward on to the guest’s knees, making himself quite comfortable. Emily’s heart was won by the unresisting endurance of the visitor, little guessing that she herself, being in close contact, was the inspiring cause of submission to Keeper’s preference. Sometimes Emily would delight in showing off Keeper—make him frantic in action, and roar with the voice of a lion. It was a terrifying exhibition within the walls of an ordinary sitting-room. Keeper was a solemn mourner at Emily’s funeral and never recovered his cheerfulness.

- Ellen Nussey, quoted in Charlotte Brontë by Rebecca Fraser (1988), p. 296

External links

- Website of the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth

- Web news magazine from the Brontë Parsonage Museum

- Selected poems of Emily Brontë

- Works by Emily Brontë at Project Gutenberg

- Emily Brontë's grave

- News and information about the Brontës using a blog format.

- Brontëana: Brontë Studies Weblog

- Wuthering Heights quotes analyzed; study guide with themes, character analyses, teaching guide