The reason we have been forcefully compelled to eke out an existence at the very lowest level of American society has to do with the nature of capitalism. ... A few wealthy capitalists are guaranteed the privilege of becoming richer and richer, whereas the people who are forced to work for the rich, and especially Black people, never take any significant step forward. ... The only true path of liberation for black people is the one that leads toward a complete and total overthrow of the capitalist class in this country and all its manifold institutional appendages.

In this country, ... where the special category of political prisoners is not officially acknowledged, the political prisoner inevitably stands trial for a specific criminal offense, not for a political act.

The American judicial system is bankrupt. In so far as black people are concerned, it has proven itself to be one more arm of a system carrying out the systematic oppression of our people. We are the victims, not the recipients of justice.

Prisons do not disappear problems, they disappear human beings. And the practice of disappearing vast numbers of people from poor, immigrant and racially marginalized communities has literally become big business.

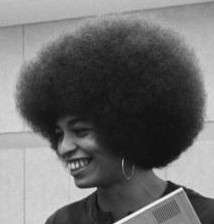

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American Communist organizer and professor who was associated with the Black Panther Party (BPP) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Davis has remained a controversial figure throughout her career as a activist and a scholar due to her affiliation with the Communist Party of America and her militant stance on African-American issues.

Quotes

It is both humiliating and humbling to discover that a single generation after the events that constructed me as a public personality, I am remembered as a hairdo.

- It is both humiliating and humbling to discover that a single generation after the events that constructed me as a public personality, I am remembered as a hairdo.

- "Afro Images: Politics, Fashion, and Nostalgia" Critical Inquiry. Vol. 21, No. 1 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 37-39, 41-43 and 45.

- Where cultural representations do not reach out beyond themselves, there is the danger that they will function as the surrogates for activism, that they will constitute both the beginning and the end of political practice.

- "Black Nationalism: The Sixties and the Nineties." Black Popular Culture, ed. Gina Dent (Seattle, Wash: Bay Press, 1992), 324.

- Progressive art can assist people to learn not only about the objective forces at work in the society in which they live, but also about the intensely social character of their interior lives. Ultimately, it can propel people toward social emancipation.

- "For a People's Culture." Political Affairs, March 1995.

- Prisons do not disappear problems, they disappear human beings. And the practice of disappearing vast numbers of people from poor, immigrant and racially marginalized communities has literally become big business.

- "Masked Racism" (1998)

- The reason i am a communist is because I believe in a total revolution which is going to overthrow the capitalist control of the economy, which will seize the wealth from all of the giant corporations that exploit and control the lives of all working people.

- From an interview.

"I am a Revolutionary Black Woman" (1970)

- in in Let Nobody Turn Us Around: Voices of Resistance, Reform, and Renewal (2000)

- I am a Communist because I am convinced that the reason we have been forcefully compelled to eke out an existence at the very lowest level of American society has to do with the nature of capitalism. If we are going to rise out of our oppression, our poverty, if we are going to cease being the targets of the racist-minded mentality of racist policemen, we will have to destroy the American capitalist system. We will have to obliterate a system in which a few wealthy capitalists are guaranteed the privilege of becoming richer and richer, whereas the people who are forced to work for the rich, and especially Black people, never take any significant step forward.

- p. 483

- My decision to join the Communist party emanated from my belief that the only true path of liberation for black people is the one that leads toward a complete and total overthrow of the capitalist class in this country and all its manifold institutional appendages which insure its ability to exploit the masses and enslave black people.

- p. 483

- The American judicial system is bankrupt. In so far as black people are concerned, it has proven itself to be one more arm of a system carrying out the systematic oppression of our people. We are the victims, not the recipients of justice.

- p. 484

If They Come in The Morning (1971)

- Political repression in the United States has reached monstrous proportions. Black and Brown peoples especially, victims of the most vicious and calculated forms of class, national and racial oppression, bear the brunt of this repression. Literally tens of thousands of innocent men and women, the overwhelming majority of them poor, fill the jails and prisons; hundreds of thousands more, including the most presumably respectable groups and individuals, are subject to police, FBI and military intelligence surveillance. The Nixon administration most recently responded to the massive protests against the war in Indochina by arresting more than 13,000 people and placing them in stadiums converted into detention centers.

- Repression is the response of an increasingly desperate imperialist ruling clique to contain an otherwise uncontrollable and growing popular disaffection leading ultimately, we think, to the revolutionary transformation of society.

- We believe that the most pressing political necessity is the consolidation of a United Front joining together all sections of the revolutionary, radical and democratic movements. Only a united front—led in the first place by the national liberation movements and the working people—can decisively counter, theoretically, ideologically and practically, the increasingly fascistic and genocidal posture of the present ruling clique

- In the heat of our pursuit for fundamental human rights, Black people have been continually cautioned to be patient. We are advised that as long as we remain faithful to the existing democratic order, the glorious moment will eventually arrive when we will come into our own as full-fledged human beings.But having been taught by bitter experience, we know that there is a glaring incongruity between democracy and the capitalist economy which is the source of our ills. Regardless of all rhetoric to the contrary, the people are not the ultimate matrix of the laws and the system which govern them—certainly not Black people and other nationally oppressed people, but not even the mass of whites. The people do not exercise decisive control over the determining factors of their lives.

- Needless to say, the history of the United States has been marred from its inception by an enormous quantity of unjust laws, far too many expressly bolstering the oppression of Black people. Particularized reflections of existing social inequities, these laws have repeatedly borne witness to the exploitative and racist core of the society itself. For Blacks, Chicanos, for all nationally oppressed people, the problem of opposing unjust laws and the social conditions which nourish their growth, has always had immediate practical implications. Our very survival has frequently been a direct function of our skill in forging effective channels of resistance. In resisting, we have sometimes been compelled to openly violate those laws which directly or indirectly buttress our oppression. But even when containing our resistance within the orbit of legality, we have been labeled criminals and have been methodically persecuted by a racist legal apparatus.

- The political prisoner’s words or deeds have in one form or another embodied political protests against the established order and have consequently brought him into acute conflict with the state. In light of the political content of his act, the “crime” (which may or may not have been committed) assumes a minor importance. In this country, however, where the special category of political prisoners is not officially acknowledged, the political prisoner inevitably stands trial for a specific criminal offense, not for a political act.

- Nat Turner and John Brown were political prisoners in their time. The acts for which they were charged and subsequently hanged, were the practical extensions of their profound commitment to the abolition of slavery.

- Racist oppression invades the lives of Black people on an infinite variety of levels. Blacks are imprisoned in a world where our labor and toil hardly allow us to eke out a decent existence, if we are able to find jobs at all. When the economy begins to falter, we are forever the first victims, always the most deeply wounded. When the economy is on its feet, we continue to live in a depressed state. Unemployment is generally twice as high in the ghettos as it is in the country as a whole and even higher among Black women and youth. The unemployment rate among Black youth has presently skyrocketed to 30 per cent. If one-third of America’s white youth were without a means of livelihood, we would either be in the thick of revolution or else under the iron rule of fascism. Substandard schools, medical care hardly fit for animals, overpriced, dilapidated housing, a welfare system based on a policy of skimpy concessions, designed to degrade and divide (and even this may soon be cancelled)—this is only the beginning of the list of props in the overall scenery of oppression which, for the mass of Blacks, is the universe.

- It goes without saying that the police would be unable to set into motion their racist machinery were they not sanctioned and supported by the judicial system. The courts not only consistently abstain from prosecuting criminal behavior on the part of the police, but they convict, on the basis of biased police testimony, countless Black men and women.

- The vicious circle linking poverty, police, courts and prison is an integral element of ghetto existence.

- The pivotal struggle which must be waged in the ranks of the working class is consequently the open, unreserved battle against entrenched racism. The white worker must become conscious of the threads which bind him to a James Johnson, Black auto worker, member of UAW, and a political prisoner presently facing charges for the killings of two foremen and a job setter. The merciless proliferation of the power of monopoly capital may ultimately push him inexorably down the very same path of desperation. No potential victim of the fascist terror should be without the knowledge that the greatest menace to racism and fascism is unity!

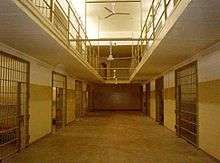

- The eternally repetitive routine, the imposed anonymity and the rigid atomization of numbers and cages are just a few of the dehumanizing, desocializing mechanisms. As for the relationship of prisoners to life outside, it is supposed to be virtually nonexistent. In this respect, the impenetrable concrete, the barbed wire and the armed keepers, ostensibly there to deter escape-bound captives, also suggest something further: prisoners must be guarded from the ingressions of a moving, developing world outside. Disengaged from normal social life, its revelations and influences, they must finally be robbed of their humanity. Yet human beings cannot be willed and molded into nonexistence. In reality the facts of prison life have begun in recent years to bespeak the irrationality of its goals. Even the most drastic repressive measures have not obstructed the progressive ascent of captive men and women to new heights of social consciousness. This has been especially intense among Black and Brown prisoners

- Chapter 2, "Lessons: From Attica to Soledad"

Women, Race and Class (1983)

- Birth control - individual choice, safe contraceptive methods, as well as abortions when necessary - is a fundamental prerequisite for the emancipation of women.

- Chapter 12, "Racism, Birth Control and Reproductive Rights"

- “Woman” was the test, but not every woman seemed to qualify. Black women, of course, were virtually invisible within the protracted campaign for woman suffrage. As for white working-class women, the suffrage leaders were probably impressed at first by the organizing efforts and militancy of their working-class sisters. But as it turned out, the working women themselves did not enthusiastically embrace the cause of woman suffrage.

- If Black people had simply accepted a status of economic and political inferiority, the mob murders would probably have subsided. But because vast numbers of ex-slaves refused to discard their dreams of progress, more than ten thousand lynchings occurred during the three decades following the war.

- The colonization of the Southern economy by capitalists from the North gave lynching its most vigorous impulse. If Black people, by means of terror and violence, could remain the most brutally exploited group within the swelling ranks of the working class, the capitalists could enjoy a double advantage. Extra profits would result from the superexploitation of Black labor, and white workers’ hostilities toward their employers would be defused. White workers who assented to lynching necessarily assumed a posture of racial solidarity with the white men who were really their oppressors. This was a critical moment in the popularization of racist ideology.

- Whoever challenged the racial hierarchy was marked a potential victim of the mob. The endless roster of the dead came to include every sort of insurgent—from the owners of successful Black businesses and workers pressing for higher wages to those who refused to be called “boy” and the defiant women who resisted white men’s sexual abuses. Yet public opinion had been captured, and it was taken for granted that lynching was a just response to the barbarous sexual crimes against white womanhood.

- As a rule, white abolitionists either defended the industrial capitalists or expressed no conscious class loyalty at all. This unquestioning acceptance of the capitalist economic system was evident in the program of the women’s rights movement as well. If most abolitionists viewed slavery as a nasty blemish which needed to be eliminated, most women’s righters viewed male supremacy in a similar manner—as an immoral flaw in their otherwise acceptable society. The leaders of the women’s rights movement did not suspect that the enslavement of Black people in the South, the economic exploitation of Northern workers and the social oppression of women might be systematically related.

- Judged by the evolving nineteenth-century ideology of femininity, which emphasized women’s roles as nurturing mothers and gentle companions and housekeepers for their husbands, Black women were practically anomalies.

Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003)

.jpg)

- Many people are familiar with the campaign to abolish the death penalty. In fact, it has already been abolished in ost countries. Even the staunchest advocates of capital punishment acknowledge the fact that the death penalty faces serious challenges. Few people find life without the death penalty difficult to imagine.

- Chapter One

- There are now thirty-three prisons, thirty eight camps, sixteen community correctional facilities, and five tiny prisoner mother facilities in California. In 2002, there were 157,979 people incarcerated in these institutions, including approximately twenty thousand people whom the state holds for immigration violations.

- Chapter One

- On the whole, people tend to take prisons for granted. It is difficult to imagine life without them At the same time, there is reluctance to face the realities hidden within them, a fear of thinking about what happens inside them. Thus, the prison is present in our lives and, at the same time, it is absent from our lives. To think about this simultaneous presence and absence is to begin to acknowledge the part played by ideology in shaping the way we interact with our social surroundings. We take prisons for granted but are often afraid to face the realities they produce.

- Chapter One

- The prison has become a black hole into which the detritus of contemporary capitalism is deposited. Mass imprisonment generates profits as it devours social wealth, and thus it tends to reproduce the very conditions that lead people to prison. There are thus real and often quite complicated connections between the deindustrialization of the economy—a process that reached its peak during the 1980s—and the rise of mass imprisonment, which also began to spiral during the Reagan-Bush era. However, the demand for more prisons was represented to the public in simplistic terms. More prisons were needed because there was more crime. Yet many scholars have demonstrated that by the time the prison construction boom began, official crime statistics were already falling.

- Chapter One

- The most immediate question today is how to prevent as many imprisoned women and men as possible back into what prisoners call "the free world." How can we move to decriminalize drug use and the trade in sexual services? How can we take seriously strategies of restorative rather than elusively punitive justice? Effective alternatives involve both transformation of the techniques for addressing "crime" and of the social and economic conditions that track som any children from poor communities, and especially communities of color, into the juvenile system and then on to prison. The most difficult and urgent challenge today is that of creatively exploring new terrain of justice, where the prison no longer serves as our major anchor.

- Chapter One

- The prison therefore functions ideologically as an abstract site into which undesirables are deposited, relieving us of the responsibility of thinking about the real issues afflicting those communities from which prisoners are drawn in such disproportionate numbers. This is the ideological work that the prison performs—it relieves us of the responsibility of seriously engaging with the problems of our society, especially those produced by racism and, increasingly, global capitalism.

- An attempt to create a new conceptual terrain for imagining alternatives to imprisonment involves the ideological work of questioning why "criminals" have been constituted as a class and, indeed, a class of human beings undeserving of the civil and human rights accorded to others. Radical criminologists have long pointed out that the category "lawbreakers" is far greater than the category of individuals who are deemed criminals since, many point out, almost all of us have broken the law at one time or another.

- The massive prison-building project that began in the 1980s created the means of concentrating and managing what the capitalist system had implicitly declared to be a human surplus. In the meantime, elected officials and the dominant media justified the new draconian sentencing practices, sending more and more people to prison in the frenzied drive to build more and more prisons by arguing that this was the only way to make our communities safe from murderers, rapists, and robbers

Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Closures and Continuities (2013)

Birkbeck Annual Law lecture at Birkbeck, University of London (25 October 2013). Transcrip

- Islamophobic violence is nurtured by histories of anti-black racist violence.

- Regimes of racial segregation were not disestablished because of the work of leaders and presidents and legislators but rather because of the fact that ordinary people adopted a critical stance in the way in which they perceived their relationship to reality. Social realities that may have appeared inalterable, impenetrable, came to be viewed as malleable and transformable; and people learned how to imagine what it might mean to live in a world that was not so exclusively governed by the principle of white supremacy. This collective consciousness emerged within the context of social struggles.

- The historical significance of the Proclamation is not so much that it enacted the emancipation of people of African descent; on the contrary, it was a military strategy. But if we examine the meaning of this historical moment we might better be able to grasp the failures as well as the successes of emancipation. I have thought that perhaps we were not asked to reflect on the significance of the Emancipation Proclamation because we might realize that we were never really emancipated. But anyway, at least we may be able to understand the dialectics of emancipation; because we still live the popular myth that Lincoln freed the slaves and that this continues to be perpetuated in popular culture, even by the film Lincoln. Lincoln did not free the slaves. We also live with the myth that the mid-twentieth century Civil Rights Movement freed the second-class citizens. Civil rights, of course, constitute an essential element of the freedom that was demanded at that time, but it was not the whole story.

- There is something for which Lincoln should be applauded, I believe. And it is that he was shrewd enough to know that the only hope of winning the Civil War resided in creating the opportunity to fight for their own freedom, and that was the significance of the Emancipation Proclamation.

- In the aftermath of the war, we find one of the most hidden eras of US history; and that is the period of radical reconstruction. It certainly remains the most radical era in the entire history of the United States of America. And this is an era that is rarely acknowledged in historical texts. ... There were progressive laws passed challenging male supremacy. This is an era that is rarely acknowledged. During that era of course we had the creation of what we now call historically black colleges and universities and there was economic development. This period didn’t last very long. From the aftermath of the abolition of slavery, we might take 1865 as that day until 1877 when a radical reconstruction was overturned—and not only was it overturned but it was erased from the historical record—and so in the 1960s we confronted issues that should have been resolved in the 1860s. One hundred years later.

- The Klu Klux Klan and the racial segregation that was so dramatically challenged during the mid-twentieth century freedom movement was produced not during slavery but rather in an attempt to manage free black people who would have been far more successful in pushing forward democracy for all.

- There is this freedom movement and then there is an attempt to narrow the freedom movement so that it fits into a much smaller frame, the frame of civil rights. Not that civil rights is not immensely important, but freedom is more expansive that civil rights. And as that movement grew and developed it was inspired by and in turn inspired liberation struggles in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Australia. It was not only a question of acquiring the formal rights to fully participate in society, but rather it was also about substantive rights—it was about jobs, free education, free health care, affordable housing, and also about ending the racist police occupation of black communities.

- When I think about the violence of my own youth in Birmingham, Alabama, where bombs were planted repeatedly and houses were destroyed and churches were destroyed and lives were destroyed and we have yet to refer to those acts as the acts of terrorists. You know terrorism which is represented as external, as outside, is very much a domestic phenomenon. Terrorism very much shaped the history of the United States of America.

- Acknowledging continuities between nineteenth century anti-slavery struggles, twentieth century civil rights struggles, twenty-first century abolitionist struggles—and when I say abolitionist struggles I’m referring to the abolition of imprisonment as the dominant mode of punishment, the abolition of the prison industrial complex—acknowledging these continuities requires a challenge to the closures that isolate the freedom movement of the twentieth century from the century preceding and the century following.

- All around the world people are saying that we want to struggle to continue as global communities, to create a world free of xenophonbia and racism, a world from which poverty has been expunged, and the availability of food is not subject to the demands of capitalist profit. I would say a world where a corporation like Monsanto would be deemed criminal. Where homophobia and transphobia can truly be called historical relics along with the punishment of incarceration and institutions of confinement for disabled people; and where everyone learns how to respect the environment and all of the creatures, human and non-human alike, with whom we cohabit our worlds.

Quotes about Angela Davis

- In our country, literally for an entire year, we heard nothing at all except Angela Davis. We had our ears stuffed with Angela Davis. Little children in school were told to sign petitions in defence of Angela Davis. Although she didn't have too difficult a time in this country's jails, she came to recuperate in Soviet resorts. Some Soviet dissidents–but more important, a group of Czech dissidents–addressed an appeal to her: 'Comrade Davis, you were in prison. You know how unpleasant it is to sit in prison, especially when you consider yourself innocent. You have such great authority now. Could you help our Czech prisoners? Could you stand up for those people in Czechoslovakia who are being persecuted by the state?' Angela Davis answered: 'They deserve what they get. Let them remain in prison.' That is the face of Communism. That is the heart of Communism for you.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Warning to the West (1986) (pp. 60-61).

External links

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.