Zeno of Citium

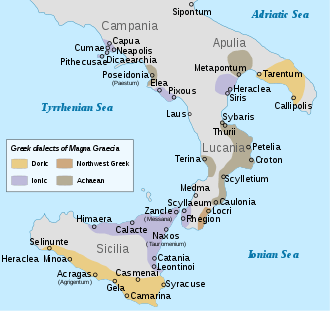

Zeno of Citium (/ˈziːnoʊ/; Greek: Ζήνων ὁ Κιτιεύς, Zēnōn ho Kitieus; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosopher of Phoenician origin [3] from Citium (Κίτιον, Kition), Cyprus. Zeno was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 BC. Based on the moral ideas of the Cynics, Stoicism laid great emphasis on goodness and peace of mind gained from living a life of Virtue in accordance with Nature. It proved very popular, and flourished as one of the major schools of philosophy from the Hellenistic period through to the Roman era.

Zeno of Citium | |

|---|---|

_-_BEIC_6353768.jpg) Zeno of Citium. Bust in the Farnese collection, Naples. Photo by Paolo Monti, 1969. | |

| Born | c. 334 BC Citium, Cyprus |

| Died | c. 262 BC |

| Era | Hellenistic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Stoicism |

Main interests | Logic, Physics, Ethics |

Notable ideas | Founder of Stoicism, three branches of philosophy (physics, ethics, logic),[1] Logos, rationality of human nature, Katalepsis, world citizenship[2] |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

Life

Zeno was born c. 334 BC,[lower-alpha 1] in Citium in Cyprus. Most of the details known about his life come from the biography and anecdotes preserved by Diogenes Laërtius in his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Diogenes reports that Zeno's interest in philosophy began when "he consulted the oracle to know what he should do to attain the best life, and that the god's response was that he should take on the complexion of the dead. Whereupon, perceiving what this meant, he studied ancient authors."[4] Zeno became a wealthy merchant. On a voyage from Phoenicia to Peiraeus he survived a shipwreck, after which he went to Athens and visited a bookseller. There he encountered Xenophon's Memorabilia. He was so pleased with the book's portrayal of Socrates that he asked the bookseller where men like Socrates were to be found. Just then, Crates of Thebes, the most famous Cynic living at that time in Greece happened to be walking by, and the bookseller pointed to him.[5]

Zeno is described as a haggard, dark-skinned person,[6] living a spare, ascetic life[7] despite his wealth. This coincides with the influences of Cynic teaching, and was, at least in part, continued in his Stoic philosophy. From the day Zeno became Crates’ pupil, he showed a strong bent for philosophy, though with too much native modesty to assimilate Cynic shamelessness. Hence Crates, desirous of curing this defect in him, gave him a potful of lentil-soup to carry through the Ceramicus; and when he saw that Zeno was ashamed and tried to keep it out of sight, Crates broke the pot with a blow of his staff. As Zeno began to run off in embarrassment with the lentil-soup flowing down his legs, Crates chided, "Why run away, my little Phoenician? Nothing terrible has befallen you."[8]

Apart from Crates, Zeno studied under the philosophers of the Megarian school, including Stilpo,[9] and the dialecticians Diodorus Cronus,[10] and Philo.[11] He is also said to have studied Platonist philosophy under the direction of Xenocrates,[12] and Polemo.[13]

Zeno began teaching in the colonnade in the Agora of Athens known as the Stoa Poikile (Greek Στοὰ Ποικίλη) in 301 BC. His disciples were initially called Zenonians, but eventually they came to be known as Stoics, a name previously applied to poets who congregated in the Stoa Poikile.

Among the admirers of Zeno was king Antigonus II Gonatas of Macedonia,[14] who, whenever he came to Athens, would visit Zeno. Zeno is said to have declined an invitation to visit Antigonus in Macedonia, although their supposed correspondence preserved by Laërtius[15] is undoubtedly the invention of a later writer.[16] Zeno instead sent his friend and disciple Persaeus,[15] who had lived with Zeno in his house.[17] Among Zeno's other pupils there were Aristo of Chios, Sphaerus, and Cleanthes who succeeded Zeno as the head (scholarch) of the Stoic school in Athens.[18]

Zeno is said to have declined Athenian citizenship when it was offered to him, fearing that he would appear unfaithful to his native land,[19] where he was highly esteemed, and where he contributed to the restoration of its baths, after which his name was inscribed upon a pillar there as "Zeno the philosopher".[20] We are also told that Zeno was of an earnest, gloomy disposition;[21] that he preferred the company of the few to the many;[22] that he was fond of burying himself in investigations;[23] and that he disliked verbose and elaborate speeches.[24] Diogenes Laërtius has preserved many clever and witty remarks by Zeno,[25] although these anecdotes are generally considered unreliable.[16]

Zeno died around 262 BC.[a] Laërtius reports about his death:

As he was leaving the school he tripped and fell, breaking his toe. Striking the ground with his fist, he quoted the line from the Niobe:

I come, I come, why dost thou call for me?and died on the spot through holding his breath.[26]

During his lifetime, Zeno received appreciation for his philosophical and pedagogical teachings. Among other things, Zeno was honored with the golden crown,[27] and a tomb was built in honor of his moral influence on the youth of his era.[28]

The crater Zeno on the Moon is named in his honour.

Philosophy

Following the ideas of the Old Academy, Zeno divided philosophy into three parts: logic (a wide subject including rhetoric, grammar, and the theories of perception and thought); physics (not just science, but the divine nature of the universe as well); and ethics, the end goal of which was to achieve eudaimonia through the right way of living according to Nature. Because Zeno's ideas were later expanded upon by Chrysippus and other Stoics it can be difficult to determine precisely what he thought. But his general views can be outlined as follows:

Logic

In his treatment of Logic, Zeno was influenced by Stilpo and the other Megarians. Zeno urged the need to lay down a basis for Logic because the wise person must know how to avoid deception.[29] Cicero accused Zeno of being inferior to his philosophical predecessors in his treatment of Logic,[30] and it seems true that a more exact treatment of the subject was laid down by his successors, including Chrysippus.[31] Zeno divided true conceptions into the comprehensible and the incomprehensible,[32] permitting for free-will the power of assent (sinkatathesis/συνκατάθεσις) in distinguishing between sense impressions.[33] Zeno said that there were four stages in the process leading to true knowledge, which he illustrated with the example of the flat, extended hand, and the gradual closing of the fist:

Zeno stretched out his fingers, and showed the palm of his hand, – "Perception," – he said, – "is a thing like this."- Then, when he had closed his fingers a little, – "Assent is like this." – Afterwards, when he had completely closed his hand, and showed his fist, that, he said, was Comprehension. From which simile he also gave that state a new name, calling it katalepsis (κατάληψις). But when he brought his left hand against his right, and with it took a firm and tight hold of his fist: – "Knowledge" – he said, was of that character; and that was what none but a wise person possessed.[34]

Physics

The Universe, in Zeno's view, is God:[35] a divine reasoning entity, where all the parts belong to the whole.[36] Into this pantheistic system he incorporated the physics of Heraclitus; the Universe contains a divine artisan-fire, which foresees everything,[37] and extending throughout the Universe, must produce everything:

Zeno, then, defines nature by saying that it is artistically working fire, which advances by fixed methods to creation. For he maintains that it is the main function of art to create and produce, and that what the hand accomplishes in the productions of the arts we employ, is accomplished much more artistically by nature, that is, as I said, by artistically working fire, which is the master of the other arts.[37]

This divine fire,[33] or aether,[38] is the basis for all activity in the Universe,[39] operating on otherwise passive matter, which neither increases nor diminishes itself.[40] The primary substance in the Universe comes from fire, passes through the stage of air, and then becomes water: the thicker portion becoming earth, and the thinner portion becoming air again, and then rarefying back into fire.[41] Individual souls are part of the same fire as the world-soul of the Universe.[42] Following Heraclitus, Zeno adopted the view that the Universe underwent regular cycles of formation and destruction.[43]

The Nature of the Universe is such that it accomplishes what is right and prevents the opposite,[44] and is identified with unconditional Fate,[45] while allowing it the free-will attributed to it.[37]

Ethics

Like the Cynics, Zeno recognised a single, sole and simple good,[46] which is the only goal to strive for.[47] "Happiness is a good flow of life," said Zeno,[48] and this can only be achieved through the use of right Reason coinciding with the Universal Reason (Logos), which governs everything. A bad feeling (pathos) "is a disturbance of the mind repugnant to Reason, and against Nature."[49] This consistency of soul, out of which morally good actions spring, is Virtue,[50] true good can only consist in Virtue.[51]

Zeno deviated from the Cynics in saying that things that are morally adiaphora (indifferent) could nevertheless have value. Things have a relative value in proportion to how they aid the natural instinct for self-preservation.[52] That which is to be preferred is a "fitting action" (kathêkon/καθῆκον), a designation Zeno first introduced. Self-preservation, and the things that contribute towards it, has only a conditional value; it does not aid happiness, which depends only on moral actions.[53]

Just as Virtue can only exist within the dominion of Reason, so Vice can only exist with the rejection of Reason. Virtue is absolutely opposed to Vice,[54] the two cannot exist in the same thing together, and cannot be increased or decreased;[55] no one moral action is more virtuous than another.[56] All actions are either good or bad, since impulses and desires rest upon free consent,[57] and hence even passive mental states or emotions that are not guided by reason are immoral,[58] and produce immoral actions.[59] Zeno distinguished four negative emotions: desire, fear, pleasure and sorrow (epithumia, phobos, hêdonê, lupê / ἐπιθυμία, φόβος, ἡδονή, λύπη),[60] and he was probably responsible for distinguishing the three corresponding positive emotions: will, caution, and joy (boulêsis, eulabeia, chara / βούλησις, εὐλάβεια, χαρά), with no corresponding rational equivalent for pain. All errors must be rooted out, not merely set aside,[61] and replaced with right reason.

Works

None of Zeno's writings have survived except as fragmentary quotations preserved by later writers. However, the titles of many of Zeno's writings are known and are as follows:[62]

- Ethical writings:

- Πολιτεία – Republic

- Περὶ τοῦ κατὰ φύσιν βίου – On Life according to Nature

- Περὶ ὁρμῆς ἢ Περὶ ἀνθρώπου φύσεως – On Impulse, or on the Nature of Humans

- Περὶ παθῶν – On Passions

- Περὶ τοῦ καθήκοντος – On Duty

- Περὶ νόμου – On Law

- Περὶ τῆς Ἑλληνικῆς παιδείας – On Greek Education

- Physical writings:

- Περὶ ὄψεως – On Sight

- Περὶ τοῦ ὅλου – On the Universe

- Περὶ σημείων – On Signs

- Πυθαγορικά – Pythagorean Doctrines

- Logical writings:

- Καθολικά – General Things

- Περὶ λέξεων

- Προβλημάτων Ὁμηρικῶν εʹ – Homeric Problems

- Περὶ ποιητικῆς ἀκροάσεως – On Poetical Readings

- Other works:

- Τέχνη

- Λύσεις – Solutions

- Ἔλεγχοι βʹ

- Ἄπομνημονεύματα Κράτητος ἠθικά

- Περὶ οὐσίας – On Being

- Περὶ φύσεως – On Nature

- Περὶ λόγου – On the Logos

- Εἰς Ἡσιόδου θεογονίαν

- Διατριβαί – Discourses

- Χρεῖαι

The most famous of these works was Zeno's Republic, a work written in conscious imitation of (or opposition to) Plato's Republic. Although it has not survived, more is known about it than any of his other works. It outlined Zeno's vision of the ideal Stoic society.

Notes

- The dates for Zeno's life are controversial. According to Apollodorus, as quoted by Philodemus, Zeno died in Arrheneides' archonship (262/1 BC). According to Persaeus (Diogenes Laërtius vii. 28), Zeno lived for 72 years. His date of birth is thus 334/3 BC. A plausible chronology for his life is as follows: He was born 334/3 BC, and came to Athens in 312/11 BC at the age of 22 (Laërtius 1925, § 28). He studied philosophy for about 10 years (Laërtius 1925, § 2); opened his own school during Clearchus' archonship in 301/0 BC (Philodemus, On the Stoics, col. 4); and was the head of the school for 39 years and 3 months (Philodemus, On the Stoics, col. 4), and died 262/1 BC. For more information see Ferguson 1911, pp. 185–186; and Dorandi 2005, p. 38

- "Stoicism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". www.iep.utm.edu. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Bunnin & Yu (2004). The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Stoics and Sceptics

- "Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, BOOK VII, Chapter 1. ZENO (333-261 B.C.)". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Laërtius 1925, § 2–3.

- Laërtius 1925, § 1.

- Laërtius 1925, § 26–27.

- Laërtius 1925, § 3.

- Laërtius 1925, § 2, 24.

- Laërtius 1925, § 16, 25.

- Laërtius 1925, § 16.

- Laërtius 1925, § 2; but note that Xenocrates died 314/13 BC

- Laërtius 1925, § 2, 25.

- Laërtius 1925, § 6–9, 13–15, 36; Epictetus, Discourses, ii. 13. 14–15; Simplicius, in Epictetus Enchiridion, 51; Aelian, Varia Historia, ix. 26

- Laërtius 1925, § 6–9.

- Brunt, P. A. (2013). "The Political Attitudes of the Old Stoa". In Griffin, Miriam; Samuels, Alison (eds.). Studies in Stoicism. Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780199695850.

- Laërtius 1925, § 13, comp. 36.

- Laërtius 1925, § 37.

- Plutarch, de Stoicor. repugn, p. 1034; comp. Laërtius 1925, § 12.

- Laërtius 1925, § 6.

- Laërtius 1925, § 16, comp. 26; Sidonius Apollinaris, Epistles, ix. 9

- Laërtius 1925, § 14.

- Laërtius 1925, § 15.

- Laërtius 1925, § 18, 22.

- Laërtius 1925, § 18–25.

- Laërtius 1925, § 28.

- Laërtius 1925, § 6, 11.

- Laërtius 1925, § 10–12.

- Cicero, Academica, ii. 20.

- Cicero, de Finibus, iv. 4.

- Sextus Empiricus, adv. Math. vii. 253.

- Cicero, Academica, ii. 6, 24.

- Cicero, Academica, i. 11.

- Cicero, Academica, 2.145 [47]

- Laërtius 1925, § 148.

- Sextus Empiricus, adv. Math. ix. 104, 101; Cicero, de Natura Deorum, ii. 8.

- Cicero, de Natura Deorum, ii. 22.

- Cicero, Academica, ii. 41.

- Cicero, de Natura Deorum, ii. 9, iii. 14.

- Laërtius 1925, § 150.

- Laërtius 1925, § 142, comp. 136.

- Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, i. 9, de Natura Deorum, iii. 14; Laërtius 1925, § 156.

- Stobaeus, Ecl. Phys. i.

- Cicero, de Natura Deorum, i. 14.

- Laërtius 1925, § 88, 148, etc., 156.

- Cicero, Academica, i. 10. 35-36 : "Zeno igitur nullo modo is erat qui ut Theophrastus nervos virtutis inciderit, sed contra qui omnia quae ad beatam vitam pertinerent in una virtute poneret nec quicquam aliud numeraret hi bonis idque appellaret honestum quod esset simplex quoddam et solum et unum bonum."

- Cicero, de Finibus, iii. 6. 8; comp. Laërtius 1925, § 100, etc.

- Stobaeus, 2.77.

- Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, iv. 6.

- Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, iv. 15.

- Laërtius 1925, § 102, 127.

- Laërtius 1925, § 85; Cicero, de Finibus, iii. 5, 15, iv. 10, v. 9, Academica, i. 16.

- Cicero, de Finibus, iii. 13.

- Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, iv. 13, Academica, i. 10, de Finibus, iii. 21, iv. 9, Parad. iii. 1; Laërtius 1925, § 127.

- Cicero, de Finibus, iii. 14, etc.

- Cicero, de Finibus, iii. 14; Sextus Empiricus, adv. Math. vii. 422.

- Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, iv. 9, Academica, i. 10.

- Laërtius 1925, § 110; Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, iv. 6. 14.

- Cicero, de Finibus, iv. 38; Plutarch, de Virt. mor.

- Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, iv. 6; Laërtius 1925, § 110.

- Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, iv. 18, etc.

- Laërtius 1925, § 4.

References

- Dorandi, Tiziano (2005). "Chapter 2: Chronology". In Algra, Keimpe; et al. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780521616706.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferguson, William Scott (1911). Hellenistic Athens: An Historical Essay. London: Macmillan. pp. 185–186.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Hunt, Harold. A Physical Interpretation of the Universe. The Doctrines of Zeno the Stoic. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1976. ISBN 0-522-84100-7

- Long, Anthony A., Sedley, David N. The Hellenistic Philosophers, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-521-27556-3

- Mason, Theodore; Scaltsas, Andrew S. (eds.). The philosophy of Zeno: Zeno of Citium and his legacy. Municipality of Larnaca. ISBN 978-9963603237.

- Pearson, Alfred C. Fragments of Zeno and Cleanthes, (1891). Greek/Latin fragments with English commentary.

- Reale, Giovanni. A History of Ancient Philosophy. III. The systems of the Hellenistic Age, (translated by John R. Catan, 1985 Zeno, the Foundation of the Stoa, and the Different Phases of Stoicism)

- Schofield, Malcolm. The Stoic Idea of the City. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-226-74006-4

- С. Аревшатян. Трактат Зенона Стоика "О Природе" и его древнеармянский перевод // Вестник Матенадарана. — Ер., 1956. — № 3. — С. 315-342.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Zeno of Citium |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zeno of Citium. |

- Zeno of Citium by Robin Turner in Sensible Marks of Ideas

- Zeno of Cittium – founder of Stoicism by Paul Harrison.

- Selected Bibliography on the Early Stoic Logicians: Zeno, Cleanthes, Chrysippus

| First | Leader of the Stoic school 300–262 BC |

Succeeded by Cleanthes |