Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin involved in the metabolism of every cell of the human body:[1][2] it is a cofactor in DNA synthesis, and in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism.[3] It is particularly important in the normal functioning of the nervous system via its role in the synthesis of myelin,[2][4] and in the maturation of developing red blood cells in the bone marrow.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | vitamin B12, vitamin B-12, cobalamin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605007 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | by mouth, sublingual, IV, IM, intranasal |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Readily absorbed in distal half of the ileum |

| Protein binding | Very high to specific transcobalamins plasma proteins. Binding of hydroxocobalamin is slightly higher than cyanocobalamin. |

| Metabolism | liver |

| Elimination half-life | Approximately 6 days (400 days in the liver) |

| Excretion | kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C63H88CoN14O14P |

| Molar mass | 1355.388 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

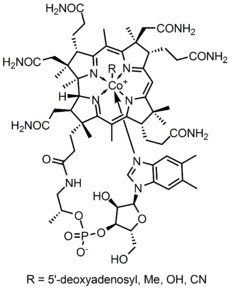

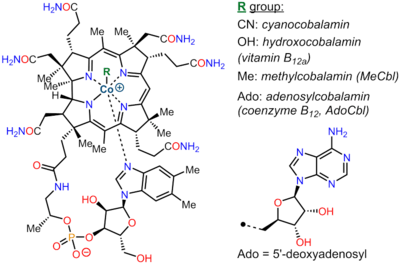

Vitamin B12 is one of eight B vitamins; it is the largest and most structurally complex vitamin.[2] The vitamin exists in four near-identical chemical forms vitamers: cyanocobalamin, hydroxocobalamin, adenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin. Cyanocobalamin and hydroxocobalamin are used to prevent or treat vitamin deficiency; once absorbed they are converted into adenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin, which are the forms which have physiological activity. All forms of vitamin B12 contain the biochemically rare element cobalt (chemical symbol Co) positioned in the center of a corrin ring. The only organisms to produce vitamin B12 are certain bacteria, and archaea. Bacteria are found on plants that herbivores eat; they are taken into the animal, proliferate and form part of their permanent gut flora, producing vitamin B12 internally.[2]

Most omnivorous people in developed countries obtain enough vitamin B12 from consuming animal products, including meat, milk, eggs, and fish.[1] Grain-based foods are often fortified by having the vitamin added to them. Vitamin B12 supplements are available in single agent or multivitamin tablets. Pharmaceutical preparations may be given by intramuscular injection.[2][6] Because there are few non-animal sources of the vitamin, vegans are advised to consume a dietary supplement or fortified foods for B12 intake, or risk serious health consequences.[2] Children in some regions of developing countries are at particular risk due to increased requirements during growth coupled with diets low in animal-sourced foods.

The most common cause of vitamin B12 deficiency in developed countries is impaired absorption due to a loss of gastric intrinsic factor, which must be bound to food-source B12 in order for absorption to occur.[2] A second major cause is age-related decline in stomach acid production (achlorhydria), because acid exposure frees protein-bound vitamin.[7] For the same reason, people on long-term antacid therapy, using proton-pump inhibitors, H2 blockers or other antacids are at increased risk.[8] Deficiency may be characterised by limb neuropathy or a blood disorder called pernicious anemia, a type of megaloblastic anemia. Folate levels in the individual may affect the course of pathological changes and symptomatology of vitamin B12 deficiency.

Definition

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin essential to the function of all cells. "Cobalamin" actually refers to a group of compounds (corrinoids) with near-identical structure. Cobalamins are characterized by a porphyrin-like corrin nucleus that contains a single cobalt atom bound to a benzimidazolyl nucleotide and a variable residue (R) group. Because these chemical compounds have a similar molecular structure, each of which shows vitamin activity in a vitamin-deficient biological system, they are referred to as vitamers. The vitamin activity is as a coenzyme, meaning that its presence is required for enzyme-catalyzed reactions.[7][9] For cyanocobalamin, the R-residue is cyanide. For hydroxocobalamin it is a hydroxyl group. Both of these can be converted to either of the two cobalamin coenzymes that are active in human metabolism: adenosylcobalamin (AdoB12) and methylcobalamin (MeB12). AdoB12 has a 5′-deoxyadenosyl group linked to the cobalt atom at the core of the molecule; MeB12 has a methyl group at that location. These enzymatically active enzyme cofactors function, respectively, in mitochondria and cell cytosol.[7]

Cyanocobalamin is a manufactured form with a cyano (cyanide) group bound to cobalt. Bacterial fermentation creates AdoB12 and MeB12 which are converted to cyanocobalamin by addition of potassium cyanide in the presence of sodium nitrite and heat. Once consumed, cyanocobalamin is converted to the biologically active AdoB12 and MeB12. Cyanocobalamin is the most common form used in dietary supplements and food fortification because cyanide stabilizes the molecule from degradation. However, methylcobalamin is also offered as a dietary supplement. Hydroxocobalamin has a hydroxyl group attached to the cobalt atom. It can be injected intramuscularly to treat Vitamin B12 deficiency. Injected intravenously, it is used to treat cyanide poisoning, as the hydroxyl group is displaced by cyanide, creating a non-toxic cyanocobalamin that is excreted in urine. "Pseudovitamin B12" refers to compounds that are corrinoids with structure similar to the vitamin but without vitamin activity.[10] Pseudovitamin B12 is the majority corrinoid in spirulina, an algal health food sometimes erroneously claimed as having this vitamin activity.[11]

Deficiency

Vitamin B12 deficiency can potentially cause severe and irreversible damage, especially to the brain and nervous system.[2][12] At levels only slightly lower than normal, a range of symptoms such as fatigue, lethargy, difficulty walking (staggering balance problems)[13] depression, poor memory, breathlessness, headaches, and pale skin, among others, may be experienced, especially in people over age 60.[2][14] Vitamin B12 deficiency can also cause symptoms of mania and psychosis.[15][16]

The main type of vitamin B 12 deficiency anemia is pernicious anemia.[17] It is characterized by a triad of symptoms:

- Anemia with bone marrow promegaloblastosis (megaloblastic anemia). This is due to the inhibition of DNA synthesis (specifically purines and thymidine)

- Gastrointestinal symptoms: alteration in bowel motility, such as mild diarrhea or constipation, and loss of bladder or bowel control.[18] These are thought to be due to defective DNA synthesis inhibiting replication in tissue sites with a high turnover of cells. This may also be due to the autoimmune attack on the parietal cells of the stomach in pernicious anemia. There is an association with GAVE syndrome (commonly called watermelon stomach) and pernicious anemia.[19]

- Neurological symptoms: Sensory or motor deficiencies (absent reflexes, diminished vibration or soft touch sensation) and subacute combined degeneration of spinal cord.[20] Deficiency symptoms in children include developmental delay, regression, irritability, involuntary movements and hypotonia.[21]

Vitamin B12 deficiency is most commonly caused by low intakes, but can also result from malabsorption, certain intestinal disorders, low presence of binding proteins, and use of certain medications.[2] Vegans—people who choose to not consume any animal-sourced foods—are at risk because plant-sourced foods do not contain the vitamin in sufficient amounts to prevent vitamin deficiency.[22] Vegetarians—people who will consume dairy products and eggs, but not the flesh of any animal—are also at risk. Vitamin B12 deficiency has been observed in between 40% to 80% of the vegetarian population who are not also consuming a vitamin B12 supplement or vitamin fortified foods.[23] In Hong Kong and India, vitamin B12 deficiency has been found in roughly 80% of the vegan population. As with vegetarians, vegans can avoid this by consuming a dietary supplement or eating B12 fortified foods such as cereals, plant-based milks, and nutritional yeast as a regular part of their diet.[24] The elderly are at increased risk because they tend to produce less stomach acid as they age, a condition known as achlorhydria, thereby increasing their probability of B12 deficiency due to reduced absorption.[1]

Pregnancy, lactation and early childhood

The U.S. Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for pregnancy is 2.6 µg/day, for lactation 2.8 µg/day. Determination of these values was based on RDA of 2.4 µg/day for non-pregnant women plus what will be transferred to the fetus during pregnancy and what will be delivered in breast milk.[7][25] However, looking at the same scientific evidence, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) sets adequate intake (AI) at 4.5 μg/day for pregnancy and 5.0 μg/day for lactation.[26] Low maternal vitamin B12, defined as serum concentration less than 148 pmol/L, increases the risk of miscarriage, newborn low birth weight and preterm birth.[27][25] During pregnancy the placenta concentrates B12, so that newborn infants have a higher serum concentration than their mothers.[7] What the mother-to-be consumes during the pregnancy is more important than her liver tissue stores, as it is recently absorbed vitamin content that more effectively reaches the placenta.[7][28] Women who consume a small percentage of their diet from animal-sourced foods or who by choice consume a vegetarian or vegan diet are at higher risk than those consuming higher amounts of animal-sourced foods for becoming vitamin depleted during pregnancy, which can lead to anemia, and also an increased risk that their breastfed infants become vitamin deficient.[28][25]

Low vitamin concentrations in human milk occur in countries and in low socioeconomic families where the consumption of animal products is low.[25] Only a few countries, primarily in Africa, have mandatory food fortification programs for either wheat flour or maize flour. India has a voluntary fortification program.[29] Also causative are women who choose to consume a vegetarian diet low in animal-sourced foods or a vegan diet, unless also consuming a dietary supplement or vitamin-fortified foods. What the nursing mother consumes is more important than her liver tissue stores, as it is recently absorbed vitamin content that more effectively reaches breast milk.[25] For both well-nourished and vitamin-depleted women, breast milk B12 decreases over months of nursing.[25] Exclusive or near-exclusive breastfeeding beyond six months is a strong indicator of low serum vitamin status in nursing infants, especially when vitamin status was poor during the pregnancy and if the early-introduction foods fed to the infants who are still breastfeeding are not animal-sourced, i.e., not providing vitamin B12.[25] Risk of deficiency persists if the post-weaning diet is low in animal-sourced foods.[25] Consequences of low vitamin status in infants and young children include anemia, poor physical growth and neurodevelopmental delays. Children diagnosed with low serum B12 can be treated with intramuscular injections, then transitioned to an oral dietary supplement.[25]

Gastric bypass surgery

Various methods of gastric bypass or gastric restriction surgery are used to treat morbid obesity. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) but not sleeve gastric bypass surgery or gastric banding, increases the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency and requires preventive post-operative treatment with either injected or high-dose oral supplementation.[30][31][32] For post-operative oral supplementation, 1000 μg/day may be needed to prevent vitamin deficiency.[32]

Diagnosis

According to one review: "At present, no ‘gold standard’ test exists for the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency and as a consequence, the diagnosis requires consideration of both the clinical state of the patient and the results of investigations."[33] The vitamin deficiency is typically suspected when a routine complete blood count shows anemia with an elevated MCV. In addition, on the peripheral blood smear, macrocytes and hypersegmented polymorphonuclear leukocytes may be seen. Diagnosis is supported based on vitamin B12 blood levels below 120–180 pmol/L (170–250 pg/mL) in adults. However, serum values can be maintained while tissue B12 stores are becoming depleted. Therefore, serum B12 values above the cut-off point of deficiency do not necessarily confirm adequate B12 status.[1] For this reason, elevated serum homocysteine over 12 μmol/L and methylmalonic acid (MMA) over 0.4 micromol/L are considered additional indicators of B12 deficiency than relying only on the concentration of B12 in blood.[1] However, elevated MMA is not conclusive, as it is seen in people with B12 deficiency, but also in elderly people who have renal insufficiency,[16] and elevated homocysteine is not conclusive, as it is also seen in people with folate deficiency.[34] If nervous system damage is present and blood testing is inconclusive, a lumbar puncture to measure cerebrospinal fluid B12 levels may be done.[35]

Medical uses

Repletion of deficiency

Severe vitamin B12 deficiency is corrected with frequent intramuscular injections of large doses of the vitamin, followed by maintenance doses of injections or oral dosing at longer intervals. One guideline specified intramuscular injections of 1000 micrograms (μg) of hydroxocobalamin three times a week for two weeks, followed by the same amount once every two or three months. Oral supplementation with 1000 or 2000 μg of cyanocobalamin every few months was mentioned as an alternative for maintenance.[36] Injection side effects include skin rash, itching, chills, fever, hot flushes, nausea and dizziness.[36]

Cyanide poisoning

For cyanide poisoning, a large amount of hydroxocobalamin may be given intravenously and sometimes in combination with sodium thiosulfate.[37] The mechanism of action is straightforward: the hydroxycobalamin hydroxide ligand is displaced by the toxic cyanide ion, and the resulting non-toxic cyanocobalamin is excreted in urine.[38]

Dietary recommendations

The U.S. Institute of Medicine (renamed National Academy of Medicine in 2015) updated estimated average requirement (EAR) and recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for vitamin B12 in 1998.[2] The EAR for vitamin B12 for women and men ages 14 and up is 2.0 μg/day; the RDA is 2.4 μg/day. RDA is higher than EAR so as to identify amounts that will cover people with higher than average requirements. RDA for pregnancy equals 2.6 μg/day. RDA for lactation equals 2.8 μg/day. For infants up to 12 months the adequate intake (AI) is 0.4–0.5 μg/day. (AIs are established when there is insufficient information to determine EARs and RDAs.) For children ages 1–13 years the RDA increases with age from 0.9 to 1.8 μg/day. Because 10 to 30 percent of older people may be unable to effectively absorb vitamin B12 naturally occurring in foods, it is advisable for those older than 50 years to meet their RDA mainly by consuming foods fortified with vitamin B12 or a supplement containing vitamin B12. As for safety, tolerable upper intake levels (known as ULs) are set for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the case of vitamin B12 there is no UL, as there is no human data for adverse effects from high doses. Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as dietary reference intakes (DRIs).[7]

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as "dietary reference values", with population reference intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and average requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL are defined by EFSA the same as in the United States. For women and men over age 18 the adequate intake (AI) is set at 4.0 μg/day. AI for pregnancy is 4.5 μg/day, for lactation 5.0 μg/day. For children aged 1–17 years the AIs increase with age from 1.5 to 3.5 μg/day. These AIs are higher than the U.S. RDAs.[39] The EFSA also reviewed the safety question and reached the same conclusion as in the United States – that there was not sufficient evidence to set a UL for vitamin B12.[40]

The Japan National Institute of Health and Nutrition set the RDA for people ages 12 and older at 2.4 μg/day.[41] The World Health Organization also uses 2.4 μg/day as the adult recommended nutrient intake for this vitamin.[42]

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount in a serving is expressed as a "percent of daily value" (%DV). For vitamin B12 labeling purposes 100% of the daily value was 6.0 μg, but on 27 May 2016, it was revised downward to 2.4 μg.[43] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided in the "Reference Daily Intake" article. The original deadline to be in compliance with the new, lower amount, was 28 July 2018, but on 29 September 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a proposed rule that extended the deadline to 1 January 2020 for large companies, and 1 January 2021 for small companies.[44]

Sources

Most omnivorous people in developed countries obtain enough vitamin B12 from consuming animal products including meat, fish, eggs, and milk.[1] Absorption is promoted by intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein; deficiencies of intrinsic factor can lead to a vitamin deficient state despite adequate consumption, as can low postprandial stomach acid production, a common failing in the aged. Vegan sources in the common food supply are rare,[45] hence the recommendations to consume a dietary supplement or fortified foods.[24]

Bacteria and archaea

Vitamin B12 is produced in nature by certain bacteria, and archaea.[46][47][48] It is synthesized by some bacteria in the gut flora in humans and other animals, but humans cannot absorb this as it is made in the colon, downstream from the small intestine, where the absorption of most nutrients occurs.[49] Ruminants, such as cows and sheep, are foregut fermenters, meaning that plant food undergoes microbial fermentation in the rumen before entering the true stomach (abomasum), and thus they are absorbing vitamin B12 produced by bacteria.[49][50] Other mammalian species (examples: rabbits, pikas, beaver, guinea pigs) consume high-fiber plants which pass through the intestinal system and undergo bacterial fermentation in the cecum and large intestine. The first-passage feces produced by this hindgut fermentation, called "cecotropes", are reingested, a practice referred to as cecotrophy or coprophagy. Reingestion allows for absorption of nutrients made available by bacterial digestion, and also of vitamins and other nutrients synthesized by the gut bacteria, including vitamin B12.[50] Non-ruminant, non-hindgut herbivores may have an enlarged forestomach and/or small intestine to provide a place for bacterial fermentation and B-vitamin product, including B12.[50] For gut bacteria to produce vitamin B12 the animal must consume sufficient amounts of cobalt.[51] Soil that is deficient in cobalt may result in B12 deficiency and B12 injections or cobalt supplementation may be required for livestock.[52]

Animal-derived foods

Animals store vitamin B12 in the liver and muscles and some pass the vitamin into their eggs and milk; meat, liver, eggs and milk are therefore sources of the vitamin for other animals as well as humans.[6][1][53] For humans, the bioavailability from eggs is less than 9%, compared to 40% to 60% from fish, fowl and meat.[54] Insects are a source of B12 for animals (including other insects, and humans).[53][55] Food sources with a high concentration of vitamin B12 include liver and other organ meats from lamb, veal, beef, and turkey; shellfish and crab meat.[2][6][56]

Plants and algae

Natural plant and algae sources of vitamin B12 include fermented plant foods such as tempeh[57][58][59] and seaweed-derived foods such as nori and laver.[45][60][61] Other types of algae are rich in B12, with some species, such as Porphyra yezoensis,[45] containing as much cobalamin as liver.[62] Methylcobalamin has been identified in Chlorella vulgaris.[63] Since only bacteria and some archea possess the genes and enzymes necessary to synthesize vitamin B12, plant and algae sources all obtain the vitamin secondarily from symbiosis with various species of bacteria,[64] or in the case of fermented plant foods, from bacterial fermentation.[57][58]

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics considers plant and algae sources "unreliable", stating that vegans should turn to fortified foods and supplements instead.[22]

Fortified foods

Vegan advocacy organizations, among others, recommend that every vegan either consume B12 from fortified foods or supplements.[2][24][65][66] Foods for which vitamin B12-fortified versions are available include breakfast cereals, plant-derived milk substitutes such as 'soy milk' and 'oat milk,' energy bars, and nutritional yeast.[56] The fortification ingredient is cyanocobalamin. Microbial fermentation yields adenosylcobalamin, which is then converted to cyanocobalamin by addition of potassium cyanide or thiocyanate in the presence of sodium nitrite and heat.[67]

As of 2019, nineteen countries require food fortification of wheat flour, maize flour or rice with vitamin B12. Most of these are in southeast Africa or Central America.[29]

Supplements

Vitamin B12 is included in multivitamin pills; in some countries grain-based foods such as bread and pasta are fortified with B12. In the US, non-prescription products can be purchased providing up to 5,000 µg each, and it is a common ingredient in energy drinks and energy shots, usually at many times the recommended dietary allowance of B12. The vitamin can also be a prescription product via injection or other means.[1]

Sublingual methylcobalamin, which contains no cyanide, is available in 5-mg tablets. The metabolic fate and biological distribution of methylcobalamin are expected to be similar to that of other sources of vitamin B12 in the diet.[68] The amount of cyanide in cyanocobalamin is not a concern, though, even in the 1,000-µg dose, since the amount of cyanide there (20 µg in a 1,000-µg cyanocobalamin tablet) is less than the daily consumption of cyanide from food, and therefore cyanocobalamin is not considered a health risk.[68]

Intramuscular or intravenous injection

Injection of hydroxocobalamin is often used if digestive absorption is impaired,[1] but this course of action may not be necessary with high-dose oral supplements (such as 0.5–1.0 mg or more),[69][70] because with large quantities of the vitamin taken orally, even the 1% to 5% of the free crystalline B12 that is absorbed along the entire intestine by passive diffusion may be sufficient to provide a necessary amount.[71]

A person with cobalamin C disease (which results in combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria) may require treatment with intravenous or intramuscular hydroxocobalamin or transdermal B12, because oral cyanocobalamin is inadequate in the treatment of cobalamin C disease.[72]

Pseudovitamin-B12

Pseudovitamin-B12 refers to B12-like analogues that are biologically inactive in humans.[10] Most cyanobacteria, including Spirulina, and some algae, such as Porphyra tenera (used to make a dried seaweed food called nori in Japan), have been found to contain mostly pseudovitamin-B12 instead of biologically active B12.[11][73] These pseudo-vitamin compounds can be found in some types of shellfish,[10] in edible insects,[74] and at times as metabolic breakdown products of cyanocobalamin added to dietary supplements and fortified foods.[75]

Pseudovitamin-B12 can show up as biologically active vitamin B12 when a microbiological assay with Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis is used, as the bacteria can utilize the pseudovitamin despite it being unavailable to humans. To get a reliable reading of B12 content, more advanced techniques are available. One such technique involves pre-separation by silica gel and then assessing with B12-dependent E. coli bacteria.[10]

Drug interactions

H2-receptor antagonists and proton-pump inhibitors

Gastric acid is needed to release vitamin B12 from protein for absorption. Reduced secretion of gastric acid and pepsin produced by H2 blocker or proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) drugs can reduce absorption of protein-bound (dietary) vitamin B12, although not of supplemental vitamin B12. H2-receptor antagonist examples include cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine, and ranitidine. PPIs examples include omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole, and esomeprazole. Clinically significant vitamin B12 deficiency and megaloblastic anemia are unlikely, unless these drug therapies are prolonged for two or more years, or if in addition the person's diet is below recommended intakes. Symptomatic vitamin deficiency is more likely if the person is rendered achlorhydric (complete absence of gastric acid secretion), which occurs more frequently with proton pump inhibitors than H2 blockers.[76]

Metformin

Reduced serum levels of vitamin B12 occur in up to 30% of people taking long-term anti-diabetic metformin.[77][78] Deficiency does not develop if dietary intake of vitamin B12 is adequate or prophylactic B12 supplementation is given. If the deficiency is detected, metformin can be continued while the deficiency is corrected with B12 supplements.[79]

Other drugs

Certain medications can decrease the absorption of orally consumed vitamin B12, including: colchicine, extended-release potassium products, and antibiotics such as gentamicin, neomycin and tobramycin.[80] Anti-seizure medications phenobarbital, pregabalin, primidone and topiramate are associated with lower than normal serum vitamin concentration. However, serum levels were higher in people prescribed valproate.[81] In addition, certain drugs may interfere with laboratory tests for the vitamin, such as amoxicillin, erythromycin, methotrexate and pyrimethamine.[80]

Chemistry

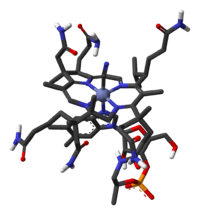

B12 is the most chemically complex of all the vitamins.[2] The structure of B12 is based on a corrin ring, which is similar to the porphyrin ring found in heme. The central metal ion is cobalt. Four of the six coordination sites are provided by the corrin ring, and a fifth by a dimethylbenzimidazole group. The sixth coordination site, the reactive center, is variable, being a cyano group (–CN), a hydroxyl group (–OH), a methyl group (–CH3) or a 5′-deoxyadenosyl group. Historically, the covalent C-Co bond is one of the first examples of carbon-metal bonds to be discovered in biology. The hydrogenases and, by necessity, enzymes associated with cobalt utilization, involve metal-carbon bonds.[82] Animals have the ability to convert cyanocobalamin and hydroxocobalamin to the bioactive forms adenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin by means of enzymatically replacing the cyano or hydroxo groups.

Vitamers

The four vitamers of B12 (see figure) are all deeply red-colored crystals due to the color of the cobalt-corrin complex. Each vitamer has a different R-group, also referred to as a ligand.

- Cyanocobalamin is a vitamer of B12 used for food fortification, multi-vitamin products and B12 dietary supplements because of its stability during processing and storage, i.e., shelf-life. It is metabolized in the body to the active coenzyme forms.[2] Bacteria are used in commercial production process to synthesize hydroxocobalamin, adenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin which are then converted to cyanocobalamin by exposure to cyanide (-CN).[83]

- Hydroxocobalamin is another vitamer of B12, commonly encountered in pharmacology. It is sometimes denoted B12a. Because it is water soluble it is used for intramuscular or intravenous injection. Hydroxocobalamin is used as an antidote to cyanide poisoning. The cyanide is bound by conversion of hydroxocobalamin to cyanocobalamin, which is then safely excreted in urine. There is some evidence that hydroxocobalamin is converted to the active enzymatic forms of B12 more easily than cyanocobalamin, so although it is more expensive than cyanocobalamin, it has been used for vitamin replacement in situations where added reassurance of activity is desired. Intramuscular administration of hydroxocobalamin is the preferred treatment for pediatric patients with intrinsic cobalamin metabolic diseases, for vitamin B12 deficient patients with tobacco amblyopia (which is thought to perhaps have a component of cyanide poisoning from cyanide in cigarette smoke); and for treatment of patients with pernicious anemia who have optic neuropathy.[84]

- Adenosylcobalamin (adoB12 or AdoCbl) is an enzymatically active cofactor form of B12 that naturally occurs in the body. Most of the body's reserves are stored as adoB12 in the liver. AdoCbl is active in the mitochondria.[85]

- Methylcobalamin (MeB12 or MeCbl) is an enzymatically active cofactor form of B12 that naturally occurs in the body. It is active in cell cytosol.[85]

Reviews of what is reported in the literature about cobalamin chemistry, transport, and processing suggests that there is unlikely to be any advantage to the use of adenosylcobalamin or methylcobalamin for treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency over using cyanocobalamin or hydroxocobalamin except possibly in very rare circumstances in which an inborn metabolic disorder reduces the efficiency of the conversion of cyanocobalamin to MeCbl or AdoCbl, in which case the use of intramuscular hydroxocobalamin is suggested. Under normal conditions, oral consumption of any of the four vitamers (or injection of hydroxocobalamin) disassociates from the ligand at the cellular level to become cobalamin, and then combines with a methyl ligand in the cytosol (to become MeCbl) or with an adenosyl ligand in mitochondria (to become AdoCbl).[84][86][87] Compared to cyanocobalamin or hydroxocobalamin, providing the vitamin as either the adenosyl or methyl vitamers does not increase the amount of .AdoCbl in mitochondria nor MeCbl in cytosol.[86] For the treatment of cyanide poisoning, injected hydroxocobalamin is the required form.[84]

Biochemistry

Coenzyme function

Vitamin B12 functions as a coenzyme, meaning that its presence is required for enzyme-catalyzed reactions.[7][9] Listed here are the three classes of enzymes that require B12 to function:

- Isomerases

- Rearrangements in which a hydrogen atom is directly transferred between two adjacent atoms with concomitant exchange of the second substituent, X, which may be a carbon atom with substituents, an oxygen atom of an alcohol, or an amine. These use the adoB12 (adenosylcobalamin) form of the vitamin.[88]

- Methyltransferases

- Methyl (–CH3) group transfers between two molecules. These use MeB12 (methylcobalamin) form of the vitamin.[89]

- Dehalogenases

In humans, two major coenzyme B12-dependent enzyme families corresponding to the first two reaction types, are known. These are typified by the following two enzymes:

Methylmalonyl Coenzyme A mutase (MUT) is an isomerase enzyme which uses the AdoB12 form and reaction type 1 to convert L-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, an important step in the catabolic breakdown of some amino acids into succinyl-CoA, which then enters energy production via the citric acid cycle.[88] This functionality is lost in vitamin B12 deficiency, and can be measured clinically as an increased serum methylmalonic acid (MMA) concentration. The MUT function is necessary for proper myelin synthesis.[87] Based on animal research, it is thought that the increased methylmalonyl-CoA hydrolyzes to form methylmalonate (methylmalonic acid), a neurotoxic dicarboxylic acid, causing neurological deterioration.[92]

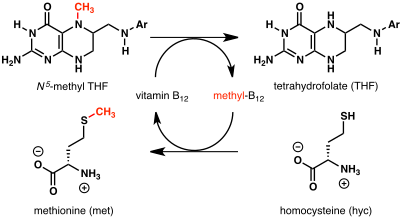

Methionine synthase, coded by MTR gene, is a methyltransferase enzyme which uses the MeB12 and reaction type 2 to transfer a methyl group from 5-methyltetrahydrofolate to homocysteine, thereby generating tetrahydrofolate (THF) and methionine.[89] This functionality is lost in vitamin B12 deficiency, resulting in an increased homocysteine level and the trapping of folate as 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate, from which THF (the active form of folate) cannot be recovered. THF plays an important role in DNA synthesis so reduced availability of THF results in ineffective production of cells with rapid turnover, in particular red blood cells, and also intestinal wall cells which are responsible for absorption. THF may be regenerated via MTR or may be obtained from fresh folate in the diet. Thus all of the DNA synthetic effects of B12 deficiency, including the megaloblastic anemia of pernicious anemia, resolve if sufficient dietary folate is present. Thus the best-known "function" of B12 (that which is involved with DNA synthesis, cell-division, and anemia) is actually a facultative function which is mediated by B12-conservation of an active form of folate which is needed for efficient DNA production.[89] Other cobalamin-requiring methyltransferase enzymes are also known in bacteria, such as Me-H4-MPT, coenzyme M methyltransferase.[93]

Physiology

Absorption

Food B12 is absorbed by two processes. The first is a vitamin B12-specific intestinal mechanism using intrinsic factor through which 1–2 micrograms can be absorbed every few hours, by which most food consumption of the vitamin is adsorbed. The second is a passive diffusion process.[7] The human physiology of active vitamin B12 absorption from food is complex. Protein-bound vitamin B12 must be released from the proteins by the action of digestive proteases in both the stomach and small intestine. Gastric acid releases the vitamin from food particles; therefore antacid and acid-blocking medications (especially proton-pump inhibitors) may inhibit absorption of B12. After B12 has been freed from proteins in food by pepsin in the stomach, R-protein (also known as haptocorrin and cobalophilin), a B12 binding protein that is produced in the salivary glands, binds to B12. This protects the vitamin from degradation in the acidic environment of the stomach.[94] This pattern of B12 transfer to a special binding protein secreted in a previous digestive step, is repeated once more before absorption. The next binding protein for B12 is intrinsic factor (IF), a protein synthesized by gastric parietal cells that is secreted in response to histamine, gastrin and pentagastrin, as well as the presence of food. In the duodenum, proteases digest R-proteins and release their bound B12, which then binds to IF, to form a complex (IF/B12). B12 must be attached to IF for it to be efficiently absorbed, as receptors on the enterocytes in the terminal ileum of the small bowel only recognize the B12-IF complex; in addition, intrinsic factor protects the vitamin from catabolism by intestinal bacteria.[7]

Absorption of food vitamin B12 thus requires an intact and functioning stomach, exocrine pancreas, intrinsic factor, and small bowel.[7] Problems with any one of these organs makes a vitamin B12 deficiency possible. Individuals who lack intrinsic factor have a decreased ability to absorb B12. In pernicious anemia, there is a lack of IF due to autoimmune atrophic gastritis, in which antibodies form against parietal cells. Antibodies may alternately form against and bind to IF, inhibiting it from carrying out its B12 protective function. Due to the complexity of B12 absorption, geriatric patients, many of whom are hypoacidic due to reduced parietal cell function, have an increased risk of B12 deficiency.[95] This results in 80–100% excretion of oral doses in the feces versus 30–60% excretion in feces as seen in individuals with adequate IF.[95]

Once the IF/B12 complex is recognized by specialized ileal receptors, it is transported into the portal circulation. The vitamin is then transferred to transcobalamin II (TC-II/B12), which serves as the plasma transporter. Hereditary defects in production of the transcobalamins and their receptors may produce functional deficiencies in B12 and infantile megaloblastic anemia, and abnormal B12 related biochemistry, even in some cases with normal blood B12 levels. For the vitamin to serve inside cells, the TC-II/B12 complex must bind to a cell receptor, and be endocytosed. The transcobalamin-II is degraded within a lysosome, and free B12 is finally released into the cytoplasm, where it may be transformed into the proper coenzyme, by certain cellular enzymes (see above).[7][96]

Investigations into the intestinal absorption of B12 point out that the upper limit of absorption per single oral dose, under normal conditions, is about 1.5 µg. The passive diffusion process of B12 absorption—normally a very small portion of total absorption of the vitamin from food consumption[7]—may exceed the R-protein and IF mediated absorption when oral doses of B12 are very large (a thousand or more µg per dose) as commonly happens in dedicated-pill oral B12 supplementation. This allows pernicious anemia and certain other defects in B12 absorption to be treated with oral megadoses of B12, even without any correction of the underlying absorption defects.[97] See the section on supplements above.

Storage and excretion

How fast B12 levels change depends on the balance between how much B12 is obtained from the diet, how much is secreted and how much is absorbed. The total amount of vitamin B12 stored in body is about 2–5 mg in adults. Around 50% of this is stored in the liver. Approximately 0.1% of this is lost per day by secretions into the gut, as not all these secretions are reabsorbed. Bile is the main form of B12 excretion; most of the B12 secreted in the bile is recycled via enterohepatic circulation. Excess B12 beyond the blood's binding capacity is typically excreted in urine. Owing to the extremely efficient enterohepatic circulation of B12, the liver can store 3 to 5 years' worth of vitamin B12; therefore, nutritional deficiency of this vitamin is rare in adults in the absence of malabsorption disorders.[7]

Production

Biosynthesis

Vitamin B12 is derived from a tetrapyrrolic structural framework created by the enzymes deaminase and cosynthetase which transform aminolevulinic acid via porphobilinogen and hydroxymethylbilane to uroporphyrinogen III. The latter is the first macrocyclic intermediate common to haem, chlorophyll, sirohaem and B12 itself.[98][99] Later steps, especially the incorporation of the additional methyl groups of its structure, were investigated using 13C methyl-labelled S-adenosyl methionine. It was not until a genetically-engineered strain of Pseudomonas denitrificans was used, in which eight of the genes involved in the biosynthesis of the vitamin had been overexpressed, that the complete sequence of methylation and other steps could be determined, thus fully establishing all the intermediates in the pathway.[100][101]

Species from the following genera and the following individual species are known to synthesize B12: Propionibacterium shermanii, Pseudomonas denitrificans, Streptomyces griseus, Acetobacterium, Aerobacter, Agrobacterium, Alcaligenes, Azotobacter, Bacillus, Clostridium, Corynebacterium, Flavobacterium, Lactobacillus, Micromonospora, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Proteus, Rhizobium, Salmonella, Serratia, Streptococcus and Xanthomonas.[102][103]

Industrial

Industrial production of B12 is achieved through fermentation of selected microorganisms.[83] Streptomyces griseus, a bacterium once thought to be a fungus, was the commercial source of vitamin B12 for many years.[104] The species Pseudomonas denitrificans and Propionibacterium freudenreichii subsp. shermanii are more commonly used today.[83] These are grown under special conditions to enhance yield. Rhone-Poulenc improved yield via genetic engineering P. denitrificans.[105] Propionibacterium, the other commonly used bacteria, produce no exotoxins or endotoxins and are generally recognized as safe (have been granted GRAS status) by the Food and Drug Administration of the United States.[106]

The total world production of vitamin B12 in 2008 was 35,000 kg (77,175 lb).[107]

Laboratory

The complete laboratory synthesis of B12 was achieved by Robert Burns Woodward[108] and Albert Eschenmoser in 1972,[109][110] and remains one of the classic feats of organic synthesis, requiring the effort of 91 postdoctoral fellows (mostly at Harvard) and 12 PhD students (at ETH Zurich) from 19 nations. The synthesis constitutes a formal total synthesis, since the research groups only prepared the known intermediate cobyric acid, whose chemical conversion to vitamin B12 was previously reported. Though it constitutes an intellectual achievement of the highest caliber, the Eschenmoser–Woodward synthesis of vitamin B12 is of no practical consequence due to its length, taking 72 chemical steps and giving an overall chemical yield well under 0.01%.[111] And although there have been sporadic synthetic efforts since 1972,[110] the Eschenmoser–Woodward synthesis remains the only completed (formal) total synthesis.

History

Five Nobel Prizes have been awarded for direct and indirect studies of vitamin B12: George Whipple, George Minot and William Murphy (1934), Alexander R. Todd (1957), and Dorothy Hodgkin (1964).[112]

- Nobel laureates for discoveries relating to Vitamin B12

George Whipple

George Whipple George Minot

George Minot William P. Murphy

William P. Murphy Alexander R. Todd

Alexander R. Todd

Descriptions of deficiency effects

Between 1849 and 1887, Thomas Addison described a case of pernicious anemia, William Osler and William Gardner first described a case of neuropathy, Hayem described large red cells in the peripheral blood in this condition, which he called "giant blood corpuscles" (now called macrocytes), Paul Ehrlich identified megaloblasts in the bone marrow, and Ludwig Lichtheim described a case of myelopathy.[5]

Identification of liver as an anti-anemia food

During the 1920s, George Whipple discovered that ingesting large amounts of liver seemed to most rapidly cure the anemia of blood loss in dogs, and hypothesized that eating liver might treat pernicious anemia.[113] Edwin Cohn prepared a liver extract that was 50 to 100 times more potent in treating pernicious anemia than the natural liver products. William Castle demonstrated that gastric juice contained an "intrinsic factor" which when combined with meat ingestion resulted in absorption of the vitamin in this condition.[5] In 1934, George Whipple shared the 1934 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with William P. Murphy and George Minot for discovery of an effective treatment for pernicious anemia using liver concentrate, later found to contain a large amount of vitamin B12.[5][114]

Identification of the active compound

While working at the Bureau of Dairy Industry, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Mary Shaw Shorb was assigned work on the bacterial strain Lactobacillus lactis Dorner (LLD), which was used to make yogurt and other cultured dairy products. The culture medium for LLD required liver extract. Shorb knew that the same liver extract was used to treat pernicious anemia (her father-in-law had died from the disease), and concluded that LLD could be developed as an assay method to identify the active compound. While at the University of Maryland she received a small grant from Merck, and in collaboration with Karl Folkers from that company, developed the LLD assay. This identified "LLD factor" as essential for the bacteria's growth.[115] Shorb, Folker and Alexander R. Todd, at the University of Cambridge, used the LLD assay to extract the anti-pernicious anemia factor from liver extracts, purify it, and name it vitamin B12.[116] In 1955, Todd helped elucidate the structure of the vitamin, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1957. The complete chemical structure of the molecule was determined by Dorothy Hodgkin, based on crystallographic data in 1956, for which for that and other crystallographic analyses she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964.[117][118] Hodgkin went on to decipher the structure of insulin.[118]

Commercial production

Industrial production of vitamin B12 is achieved through fermentation of selected microorganisms.[83] As noted above, the completely synthetic laboratory synthesis of B12 was achieved by Robert Burns Woodward and Albert Eschenmoser in 1972. That process has no commercial potential, as it requires close to 70 steps and has a yield well below 0.01%.[111]

Society and culture

In the 1970s John A. Myers, a physician residing in Baltimore, developed a program of injecting vitamins and minerals intravenously for various medical conditions. The formula included 1000 µg of cyanocobalamin. This came to be known as Myers' cocktail. After his death in 1984, other physicians and naturopaths took up prescribing “intravenous micro-nutrient therapy” with unsubstantiated health claims for treating fatigue, low energy, stress, anxiety, migraine, depression, immunocompromised, promoting weight loss and more.[119] However, other than a report on case studies[119] there are no benefits confirmed in the scientific literature.[120] Healthcare practitioners at clinics and spas prescribe versions of these intravenous combination products, but also intramuscular injections of just vitamin B12. A Mayo Clinic review concluded that there is no solid evidence that vitamin B12 injections provide an energy boost or aid weight loss.[121]

There is evidence that for elderly people, physicians often repeatedly prescribe and administer cyanocobalamin injections inappropriately, evidenced by the majority of subjects in one large study either having had normal serum concentrations or had not been tested prior to the injections.[122]

References

- "Vitamin B12: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. 9 July 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Vitamin B12". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 4 June 2015. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Yamada K (2013). "Cobalt: Its Role in Health and Disease". In Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 13. Springer. pp. 295–320. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_9. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470095.

- Miller A, Korem M, Almog R, Galboiz Y (June 2005). "Vitamin B12, demyelination, remyelination and repair in multiple sclerosis". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 233 (1–2): 93–7. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2005.03.009. PMID 15896807.

- Greer JP (2014). Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology Thirteenth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-7268-3. Chapter 36: Megaloblastic anemias: disorders of impaired DNA synthesis by Ralph Carmel

- "Foods highest in Vitamin B12 (based on levels per 100-gram serving)". Nutrition Data. Condé Nast, USDA National Nutrient Database, release SR-21. 2014. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- Institute of Medicine (1998). "Vitamin B12". Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 306–356. ISBN 978-0-309-06554-2. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- "Acid-Reflux Drugs Tied to Lower Levels of Vitamin B-12". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

- Banerjee R, Ragsdale SW (July 2003). "The many faces of vitamin B12: catalysis by cobalamin-dependent enzymes". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 72: 209–47. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161828. PMID 14527323.

- Watanabe F, Bito T (September 2018). "Determination of Cobalamin and Related Compounds in Foods". J AOAC Int. 101 (5): 1308–1313. doi:10.5740/jaoacint.18-0045. PMID 29669618.

- Watanabe F, Katsura H, Takenaka S, Fujita T, Abe K, Tamura Y, Nakatsuka T, Nakano Y (November 1999). "Pseudovitamin B(12) is the predominant cobamide of an algal health food, spirulina tablets". J. Agric. Food Chem. 47 (11): 4736–41. doi:10.1021/jf990541b. PMID 10552882.

- van der Put NM, van Straaten HW, Trijbels FJ, Blom HJ (April 2001). "Folate, homocysteine and neural tube defects: an overview". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 226 (4): 243–70. doi:10.1177/153537020122600402. PMID 11368417.

- Skerrett, Patrick J. (February 2019). "Vitamin B12 deficiency can be sneaky, harmful". Harvard Health Blog. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency anaemia – Symptoms". National Health Service, England. 23 May 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, Rudoy I, Volkov I, Wirguin I (September 2001). "Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency". The Israel Medical Association Journal. 3 (9): 701–3. PMID 11574992.

- Lachner C, Steinle NI, Regenold WT (2012). "The neuropsychiatry of vitamin B12 deficiency in elderly patients". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 24 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11020052. PMID 22450609.

- "What Is Pernicious Anemia?". NHLBI. April 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- Briani C, Dalla Torre C, Citton V, Manara R, Pompanin S, Binotto G, Adami F (November 2013). "Cobalamin Deficiency: Clinical Picture and Radiological Findings". Nutrients. 5 (11): 4521–39. doi:10.3390/nu5114521. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 3847746. PMID 24248213.

- Amarapurka DN, Patel ND (September 2004). "Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE) Syndrome" (PDF). Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 52: 757. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Greenburg, Mark (2010). Handbook of Neurosurgery 7th Edition. New York: Thieme Publishers. pp. 1187–1188. ISBN 978-1-60406-326-4.

- Kliegman, Robert M.; Stanton, Bonita; St. Geme, Joseph; Schor, Nina F, eds. (2016). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (20th ed.). pp. 2319–2326. ISBN 978-1-4557-7566-8.

- Melina V, Craig W, Levin S (2016). "Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets". J Acad Nutr Diet. 116 (12): 1970–1980. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025. PMID 27886704.

Fermented foods (such as tempeh), nori, spirulina, chlorella algae, and unfortified nutritional yeast cannot be relied upon as adequate or practical sources of B-12.39,40 Vegans must regularly consume reliable sources— meaning B-12 fortified foods or B-12 containing supplements—or they could become deficient, as shown in case studies of vegan infants, children, and adults.

- Pawlak R, Parrott SJ, Raj S, Cullum-Dugan D, Lucus D (February 2013). "How prevalent is vitamin B(12) deficiency among vegetarians?". Nutrition Reviews. 71 (2): 110–7. doi:10.1111/nure.12001. PMID 23356638.

- Woo KS, Kwok TC, Celermajer DS (August 2014). "Vegan diet, subnormal vitamin B-12 status and cardiovascular health". Nutrients. 6 (8): 3259–73. doi:10.3390/nu6083259. PMC 4145307. PMID 25195560.

- Obeid R, Murphy M, Solé-Navais P, Yajnik C (November 2017). "Cobalamin Status from Pregnancy to Early Childhood: Lessons from Global Experience". Adv Nutr. 8 (6): 971–79. doi:10.3945/an.117.015628. PMC 5683008. PMID 29141978.

- "Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies" (PDF). 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-07. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- Rogne T, Tielemans MJ, Chong MF, Yajnik CS, Krishnaveni GV, Poston L, et al. (February 2017). "Associations of Maternal Vitamin B12 Concentration in Pregnancy With the Risks of Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data". Am J Epidemiol. 185 (3): 212–23. doi:10.1093/aje/kww212. PMC 5390862. PMID 28108470.

- Sebastiani G, Herranz Barbero A, Borrás-Novell C, Alsina Casanova M, Aldecoa-Bilbao V, Andreu-Fernández V, Pascual Tutusaus M, Ferrero Martínez S, Gómez Roig MD, García-Algar O (March 2019). "The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diet during Pregnancy on the Health of Mothers and Offspring". Nutrients. 11 (3): 557. doi:10.3390/nu11030557. PMC 6470702. PMID 30845641.

- "Map: Count of Nutrients In Fortification Standards". Global Fortification Data Exchange. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Weng TC, Chang CH, Dong YH, Chang YC, Chuang LM (July 2015). "Anaemia and related nutrient deficiencies after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 5 (7): e006964. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006964. PMC 4513480. PMID 26185175.

- Majumder S, Soriano J, Louie Cruz A, Dasanu CA (2013). "Vitamin B12 deficiency in patients undergoing bariatric surgery: preventive strategies and key recommendations". Surg Obes Relat Dis. 9 (6): 1013–9. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2013.04.017. PMID 24091055.

- Mahawar KK, Reid A, Graham Y, Callejas-Diaz L, Parmar C, Carr WR, Jennings N, Singhal R, Small PK (July 2018). "Oral Vitamin B12 Supplementation After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: a Systematic Review". Obes Surg. 28 (7): 1916–23. doi:10.1007/s11695-017-3102-y. PMID 29318504.

- Shipton MJ, Thachil J (April 2015). "Vitamin B12 deficiency - A 21st century perspective". Clin Med (Lond). 15 (2): 145–50. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.15-2-145. PMC 4953733. PMID 25824066.

- Moretti R, Caruso P (January 2019). "The Controversial Role of Homocysteine in Neurology: From Labs to Clinical Practice". Int J Mol Sci. 20 (1). doi:10.3390/ijms20010231. PMC 6337226. PMID 30626145.

- Devalia V (Aug 2006). "Diagnosing vitamin B-12 deficiency on the basis of serum B-12 assay". BMJ. 333 (7564): 385–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.333.7564.385. PMC 1550477. PMID 16916826.

- Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM (August 2014). "Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders". Br. J. Haematol. 166 (4): 496–513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959. PMID 24942828.

- Hall AH, Rumack BH (1987). "Hydroxycobalamin/sodium thiosulfate as a cyanide antidote". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 5 (2): 115–121. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(87)90074-6. PMID 3295013.

- Dart RC (2006). "Hydroxocobalamin for acute cyanide poisoning: new data from preclinical and clinical studies; new results from the prehospital emergency setting". Clinical Toxicology. 44 Suppl 1 (Suppl. 1): 1–3. doi:10.1080/15563650600811607. PMID 16990188.

- "Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies" (PDF). 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-07. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- "Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals" (PDF). European Food Safety Authority. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese 2010: Water-Soluble Vitamins Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 2013(59):S67-S82.

- World Health Organization (2005). "Chapter 14: Vitamin B12". Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 279–287. hdl:10665/42716. ISBN 978-92-4-154612-6.

- "Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels" (PDF). Federal Register. May 27, 2016. p. 33982. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 18, 2019. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Watanabe F, Yabuta Y, Bito T, Teng F (May 2014). "Vitamin B₁₂-containing plant food sources for vegetarians". Nutrients. 6 (5): 1861–73. doi:10.3390/nu6051861. PMC 4042564. PMID 24803097.

- Fang H, Kang J, Zhang D (January 2017). "12: a review and future perspectives". Microbial Cell Factories. 16 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/s12934-017-0631-y. PMC 5282855. PMID 28137297.

- Moore SJ, Warren MJ (June 2012). "The anaerobic biosynthesis of vitamin B12". Biochemical Society Transactions. 40 (3): 581–6. doi:10.1042/BST20120066. PMID 22616870.

- Graham RM, Deery E, Warren MJ (2009). "18: Vitamin B12: Biosynthesis of the Corrin Ring". In Warren MJ, Smith AG (eds.). Tetrapyrroles Birth, Life and Death. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. p. 286. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-78518-9_18. ISBN 978-0-387-78518-9.

- Gille D, Schmid A (February 2015). "Vitamin B12 in meat and dairy products". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (2): 106–15. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuu011. PMID 26024497.

- Stevens CE, Hume ID (April 1998). "Contributions of microbes in vertebrate gastrointestinal tract to production and conservation of nutrients". Physiol. Rev. 78 (2): 393–427. doi:10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.393. PMID 9562034.

- McDowell LR (2008). Vitamins in Animal and Human Nutrition (2nd ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 525, 539. ISBN 9780470376683. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2017-01-17.

- "Cobalt deficiency in sheep and cattle". www.agric.wa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2015-11-11. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- Rooke J (October 30, 2013). "Do carnivores need Vitamin B12 supplements?". Baltimore Post Examiner. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- Watanabe F (November 2007). "Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailability". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 232 (10): 1266–74. doi:10.3181/0703-MR-67. PMID 17959839.

- Dossey AT (February 1, 2013). "Why Insects Should Be in Your Diet". The Scientist. Archived from the original on November 11, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "Vitamin B-12 (µg)" (PDF). USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 28. 27 October 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Liem IT, Steinkraus KH, Cronk TC (December 1977). "Production of vitamin B-12 in tempeh, a fermented soybean food". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 34 (6): 773–6. doi:10.1128/AEM.34.6.773-776.1977. PMC 242746. PMID 563702.

- Keuth S, Bisping B (May 1994). "Vitamin B12 production by Citrobacter freundii or Klebsiella pneumoniae during tempeh fermentation and proof of enterotoxin absence by PCR" (PDF). Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 60 (5): 1495–9. doi:10.1128/AEM.60.5.1495-1499.1994. PMC 201508. PMID 8017933. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Mo H, Kariluoto S, Piironen V, Zhu Y, Sanders MG, Vincken JP, et al. (December 2013). "Effect of soybean processing on content and bioaccessibility of folate, vitamin B12 and isoflavones in tofu and tempe". Food Chemistry. 141 (3): 2418–25. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.017. PMID 23870976.

- Kwak CS, Lee MS, Lee HJ, Whang JY, Park SC (June 2010). "Dietary source of vitamin B(12) intake and vitamin B(12) status in female elderly Koreans aged 85 and older living in rural area". Nutrition Research and Practice. 4 (3): 229–234. doi:10.4162/nrp.2010.4.3.229. PMC 2895704. PMID 20607069.

- Kwak CS, Lee MS, Oh SI, Park SC (2010). "Discovery of novel sources of vitamin b(12) in traditional korean foods from nutritional surveys of centenarians". Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2010: 374897. doi:10.1155/2010/374897. PMC 3062981. PMID 21436999.

- Croft MT, Lawrence AD, Raux-Deery E, Warren MJ, Smith AG (November 2005). "Algae acquire vitamin B12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria". Nature. 438 (7064): 90–3. Bibcode:2005Natur.438...90C. doi:10.1038/nature04056. PMID 16267554.

- Kumudha A, Selvakumar S, Dilshad P, Vaidyanathan G, Thakur MS, Sarada R (March 2015). "Methylcobalamin--a form of vitamin B12 identified and characterised in Chlorella vulgaris". Food Chemistry. 170: 316–20. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.08.035. PMID 25306351.

- Smith, AG; et al. (2019-09-21). "Plants need their vitamins too". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 10 (3): 266–75. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.009. PMID 17434786.

- Mangels R. "Vitamin B12 in the Vegan Diet". Vegetarian Resource Group. Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- "Don't Vegetarians Have Trouble Getting Enough Vitamin B12?". Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- Martins JH, Barg H, Warren MJ, Jahn D (March 2002). "Microbial production of vitamin B12". Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 58 (3): 275–85. doi:10.1007/s00253-001-0902-7. PMID 11935176.

- European Food Safety Authority (September 25, 2008). "5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin as sources for Vitamin B12 added as a nutritional substance in food supplements: Scientific opinion of the Scientific Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to food". EFSA Journal. 815 (10): 1–21. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2008.815. "the metabolic fate and biological distribution of methylcobalamin and 5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin are expected to be similar to that of other sources of vitamin B12 in the diet."

- Lane LA, Rojas-Fernandez C (July–August 2002). "Treatment of vitamin b(12)-deficiency anemia: oral versus parenteral therapy". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (7–8): 1268–72. doi:10.1345/aph.1A122. PMID 12086562.

- Butler CC, Vidal-Alaball J, Cannings-John R, McCaddon A, Hood K, Papaioannou A, Mcdowell I, Goringe A (June 2006). "Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Family Practice. 23 (3): 279–85. doi:10.1093/fampra/cml008. PMID 16585128.

- Arslan SA, Arslan I, Tirnaksiz F (March 2013). "Cobalamins and Methylcobalamin: Coenzyme of Vitamin B12" (PDF). FABAD J. Pharm. Sci. 38 (3): 151–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-04. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Thauvin-Robinet C, Roze E, Couvreur G, Horellou MH, Sedel F, Grabli D, Bruneteau G, Tonneti C, Masurel-Paulet A, Perennou D, Moreau T, Giroud M, de Baulny HO, Giraudier S, Faivre L (June 2008). "The adolescent and adult form of cobalamin C disease: clinical and molecular spectrum". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 79 (6): 725–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.133025. PMID 18245139.

- Yamada K, Yamada Y, Fukuda M, Yamada S (November 1999). "Bioavailability of Dried Asakusanori (Porphyra tenera) as a Source of Cobalamin (Vitamin B12)". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 69 (6): 412–8. doi:10.1024/0300-9831.69.6.412. PMID 10642899.

- Schmidt A, Call LM, Macheiner L, Mayer HK (May 2019). "Determination of vitamin B12 in four edible insect species by immunoaffinity and ultra-high performance liquid chromatography". Food Chemistry. 281: 124–129. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.039. PMID 30658738.

- Yamada K, Shimodaira M, Chida S, Yamada N, Matsushima N, Fukuda M, Yamada S (2008). "Degradation of vitamin B12 in dietary supplements". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 78 (4–5): 195–203. doi:10.1024/0300-9831.78.45.195. PMID 19326342.

- DeVault KR, Talley NJ (September 2009). "Insights into the future of gastric acid suppression". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6 (9): 524–532. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2009.125. PMID 19713987.

- Ahmed, MA (2016). "Metformin and Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Where Do We Stand?". Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 19 (3): 382–398. doi:10.18433/J3PK7P. PMID 27806244.

- Gilligan MA (February 2002). "Metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency". Archives of Internal Medicine. 162 (4): 484–85. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.4.484. PMID 11863489.

- Copp S (1 December 2007). "What effect does metformin have on vitamin B12 levels?". UK Medicines Information, NHS. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- "Vitamin B-12: Interactions". WebMD. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Linnebank M, Moskau S, Semmler A, Widman G, Stoffel-Wagner B, Weller M, Elger CE (February 2011). "Antiepileptic drugs interact with folate and vitamin B12 serum levels". Ann. Neurol. 69 (2): 352–9. doi:10.1002/ana.22229. PMID 21246600.

- Jaouen G, ed. (2006). Bioorganometallics: Biomolecules, Labeling, Medicine. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-30990-0.

- Fang H, Kang J, Zhang D (January 2017). "Microbial production of vitamin B12: a review and future perspectives". Microb. Cell Fact. 16 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/s12934-017-0631-y. PMC 5282855. PMID 28137297.

- Obeid R, Fedosov SN, Nexo E (July 2015). "Cobalamin coenzyme forms are not likely to be superior to cyano- and hydroxyl-cobalamin in prevention or treatment of cobalamin deficiency". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 59 (7): 1364–72. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201500019. PMC 4692085. PMID 25820384.

- Gherasim C, Lofgren M, Banerjee R (May 2013). "Navigating the B(12) road: assimilation, delivery, and disorders of cobalamin". J. Biol. Chem. 288 (19): 13186–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.R113.458810. PMC 3650358. PMID 23539619.

- Paul C, Brady DM (February 2017). "Comparative Bioavailability and Utilization of Particular Forms of B12 Supplements With Potential to Mitigate B12-related Genetic Polymorphisms". Integr Med (Encinitas). 16 (1): 42–49. PMC 5312744. PMID 28223907.

- Calderón-Ospina CA, Nava-Mesa MO (January 2020). "B Vitamins in the nervous system: Current knowledge of the biochemical modes of action and synergies of thiamine, pyridoxine, and cobalamin". CNS Neurosci Ther. 26 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1111/cns.13207. PMC 6930825. PMID 31490017.

- Takahashi-Iñiguez T, García-Hernandez E, Arreguín-Espinosa R, Flores ME (June 2012). "Role of vitamin B12 on methylmalonyl-CoA mutase activity". J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 13 (6): 423–37. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1100329. PMC 3370288. PMID 22661206.

- Froese DS, Fowler B, Baumgartner MR (July 2019). "Vitamin B12, folate, and the methionine remethylation cycle-biochemistry, pathways, and regulation". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 42 (4): 673–685. doi:10.1002/jimd.12009. PMID 30693532.

- Reinhold A, Westermann M, Seifert J, von Bergen M, Schubert T, Diekert G (November 2012). "Impact of vitamin B12 on formation of the tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase in Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain Y51". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 (22): 8025–32. doi:10.1128/AEM.02173-12. PMC 3485949. PMID 22961902.

- Payne KA, Quezada CP, Fisher K, Dunstan MS, Collins FA, Sjuts H, Levy C, Hay S, Rigby SE, Leys D (January 2015). "Reductive dehalogenase structure suggests a mechanism for B12-dependent dehalogenation". Nature. 517 (7535): 513–16. doi:10.1038/nature13901. PMC 4968649. PMID 25327251.

- Ballhausen D, Mittaz L, Boulat O, Bonafé L, Braissant O (December 2009). "Evidence for catabolic pathway of propionate metabolism in CNS: expression pattern of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase and propionyl-CoA carboxylase alpha-subunit in developing and adult rat brain". Neuroscience. 164 (2): 578–87. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.028. PMID 19699272.

- Marsh EN (1999). "Coenzyme B12 (cobalamin)-dependent enzymes". Essays Biochem. 34: 139–54. doi:10.1042/bse0340139. PMID 10730193.

- Allen RH, Seetharam B, Podell E, Alpers DH (January 1978). "Effect of proteolytic enzymes on the binding of cobalamin to R protein and intrinsic factor. In vitro evidence that a failure to partially degrade R protein is responsible for cobalamin malabsorption in pancreatic insufficiency". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 61 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1172/JCI108924. PMC 372512. PMID 22556.

- Combs GF (2008). The vitamins: fundamental aspects in nutrition and health (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 381–398. ISBN 978-0-12-183492-0. OCLC 150255807.

- Al-Awami HM, Raja A, Soos MP (August 2019). "Physiology, Intrinsic Factor (Gastric Intrinsic Factor)". StatPearls [Internet]. PMID 31536261.

- Kuzminski AM, Del Giacco EJ, Allen RH, Stabler SP, Lindenbaum J (August 1998). "Effective treatment of cobalamin deficiency with oral cobalamin". Blood. 92 (4): 1191–8. doi:10.1182/blood.V92.4.1191. PMID 9694707.

- Battersby AR, Fookes CJ, Matcham GW, McDonald E (May 1980). "Biosynthesis of the pigments of life: formation of the macrocycle". Nature. 285 (5759): 17–21. doi:10.1038/285017a0. PMID 6769048.

- Frank S, Brindley AA, Deery E, Heathcote P, Lawrence AD, Leech HK, et al. (August 2005). "Anaerobic synthesis of vitamin B12: characterization of the early steps in the pathway". Biochemical Society Transactions. 33 (Pt 4): 811–4. doi:10.1042/BST0330811. PMID 16042604.

- Battersby, AR (1993). "How Nature builds the pigments of life" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (6): 1113–22. doi:10.1351/pac199365061113. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-24. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- Battersby A (2005). "Chapter 11: Discovering the wonder of how Nature builds its molecules". In Archer MD, Haley CD (eds.). The 1702 chair of chemistry at Cambridge: transformation and change. Cambridge University Press. pp. xvi, 257–82. ISBN 0521828732.

- Perlman D (1959). "Microbial synthesis of cobamides". Advances in Applied Microbiology. 1: 87–122. doi:10.1016/S0065-2164(08)70476-3. ISBN 9780120026012. PMID 13854292.

- Martens JH, Barg H, Warren MJ, Jahn D (March 2002). "Microbial production of vitamin B12". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 58 (3): 275–85. doi:10.1007/s00253-001-0902-7. PMID 11935176.

- Linnell JC, Matthews DM (February 1984). "Cobalamin metabolism and its clinical aspects". Clinical Science. 66 (2): 113–121. doi:10.1042/cs0660113. PMID 6420106.

- Piwowarek K, Lipińska E, Hać-Szymańczuk E, Kieliszek M, Ścibisz I (January 2018). "Propionibacterium spp.-source of propionic acid, vitamin B12, and other metabolites important for the industry". Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102 (2): 515–538. doi:10.1007/s00253-017-8616-7. PMC 5756557. PMID 29167919.

- Riaz M, Iqbal F, Akram M (2007). "Microbial production of vitamin B12 by methanol utilizing strain of Pseudomonas species". Pakistan Journal of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 1. 40: 5–10.

- Zhang Y (January 26, 2009). "New round of price slashing in vitamin B12 sector (Fine and Specialty)". China Chemical Reporter. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013.

- Khan AG, Eswaran SV (June 2003). "Woodward's synthesis of vitamin B12". Resonance. 8 (6): 8–16. doi:10.1007/BF02837864.

- Eschenmoser A, Wintner CE (June 1977). "Natural product synthesis and vitamin B12". Science. 196 (4297): 1410–20. Bibcode:1977Sci...196.1410E. doi:10.1126/science.867037. PMID 867037.

- Riether D, Mulzer J (2003). "Total Synthesis of Cobyric Acid: Historical Development and Recent Synthetic Innovations". European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2003: 30–45. doi:10.1002/1099-0690(200301)2003:1<30::AID-EJOC30>3.0.CO;2-I.

- "Synthesis of Cyanocobalamin by Robert B. Woodward (1973)". www.synarchive.com. Archived from the original on 2018-02-16. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- "The Nobel Prize and the Discovery of Vitamins". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2018-01-16. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- "George H. Whipple – Biographical". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-13. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1934 Archived 2017-10-02 at the Wayback Machine, Nobelprize.org, Nobel Media AB 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- "Mary Shorb Lecture in Nutrition". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Shorb MS (May 10, 2012). "Annual Lecture". Department of Animal & Avian Sciences, University of Maryland. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- Hodgkin DC, Kamper J, Mackay M, Pickworth J, Trueblood KN, White JG (July 1956). "Structure of vitamin B12". Nature. 178 (4524): 64–6. Bibcode:1956Natur.178...64H. doi:10.1038/178064a0. PMID 13348621.

- Dodson, G (December 2002). "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M. 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 48: 179–219. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0011. ISSN 0080-4606.

- Gaby AR (October 2002). "Intravenous nutrient therapy: the "Myers' cocktail"". Altern Med Rev. 7 (5): 389–403. PMID 12410623.

- Gavura S (24 May 2013). "A closer look at vitamin injections". Science-Based Medicine. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Bauer BA (29 March 2018). "Are vitamin B-12 injections helpful for weight loss?". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Silverstein WK, Lin Y, Dharma C, Croxford R, Earle CC, Cheung MC (July 2019). "Prevalence of Inappropriateness of Parenteral Vitamin B12 Administration in Ontario, Canada". JAMA Internal Medicine. 179 (10): 1434. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1859. ISSN 2168-6106. PMC 6632124. PMID 31305876.

External links

- Cyanocobalamin at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "Cyanocobalamin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Hydroxocobalamin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Methylcobalamin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Adenosylcobalamin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.