Viral envelope

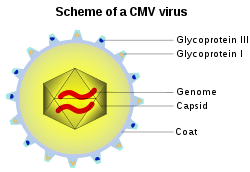

Most viruses (e.g. HIV and many animal viruses) have viral envelopes as their outer layer[1] at the stage of their life-cycle when they are between host cells. The envelopes are typically derived from portions of the host cell membranes (phospholipids and proteins), but include some viral glycoproteins. They may help viruses avoid the host immune system. Glycoproteins on the surface of the envelope serve to identify and bind to receptor sites on the host's membrane. The viral envelope then fuses with the host's membrane, allowing the capsid and viral genome to enter and infect the host.

The cell from which the virus itself buds will often die or be weakened and shed more viral particles for an extended period. The lipid bilayer envelope of these viruses is relatively sensitive to desiccation, heat, and detergents, therefore these viruses are easier to sterilize than non-enveloped viruses, have limited survival outside host environments, and typically transfer directly from host to host. Enveloped viruses possess great adaptability and can change in a short time in order to evade the immune system. Enveloped viruses can cause persistent infections.

Enveloped examples

Classes of enveloped viruses that contain human pathogens:

DNA viruses

- Herpesvirus

- Poxviruses

- Hepadnaviruses

- Asfarviridae

RNA viruses

- Flavivirus

- Alphavirus

- Togavirus

- Coronavirus

- Hepatitis D

- Orthomyxovirus

- Paramyxovirus

- Rhabdovirus[2]

- Bunyavirus

- Filovirus

Retroviruses

- Retroviruses - env

Nonenveloped examples

Classes of nonenveloped viruses that contain human pathogens:

DNA viruses

RNA viruses

- Picornaviridae

- Caliciviridae

See also

- Bacterial capsule

- Cell envelope

References

- "CHAPTER #11: VIRUSES". Archived from the original on 2008-11-10. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- "The Rabies Virus". CDC. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

External links

- "Virus Structure". Molecular Expressions: Images from the Microscope. Retrieved 2007-06-27.