March equinox

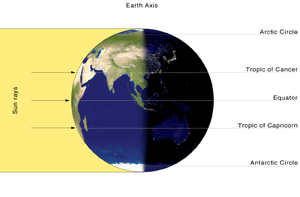

The March equinox[3][4] or Northward equinox[5][6] is the equinox on the Earth when the subsolar point appears to leave the Southern Hemisphere and cross the celestial equator, heading northward as seen from Earth. The March equinox is known as the vernal equinox (spring equinox) in the Northern Hemisphere and as the autumnal equinox in the Southern.[4][3][7]

| event | equinox | solstice | equinox | solstice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| month | March | June | September | December | ||||

| year | ||||||||

| day | time | day | time | day | time | day | time | |

| 2015 | 20 | 22:45 | 21 | 16:38 | 23 | 08:21 | 22 | 04:48 |

| 2016 | 20 | 04:30 | 20 | 22:34 | 22 | 14:21 | 21 | 10:44 |

| 2017 | 20 | 10:28 | 21 | 04:24 | 22 | 20:02 | 21 | 16:28 |

| 2018 | 20 | 16:15 | 21 | 10:07 | 23 | 01:54 | 21 | 22:23 |

| 2019 | 20 | 21:58 | 21 | 15:54 | 23 | 07:50 | 22 | 04:19 |

| 2020 | 20 | 03:50 | 20 | 21:44 | 22 | 13:31 | 21 | 10:02 |

| 2021 | 20 | 09:37 | 21 | 03:32 | 22 | 19:21 | 21 | 15:59 |

| 2022 | 20 | 15:33 | 21 | 09:14 | 23 | 01:04 | 21 | 21:48 |

| 2023 | 20 | 21:24 | 21 | 14:58 | 23 | 06:50 | 22 | 03:27 |

| 2024 | 20 | 03:07 | 20 | 20:51 | 22 | 12:44 | 21 | 09:20 |

| 2025 | 20 | 09:02 | 21 | 02:42 | 22 | 18:20 | 21 | 15:03 |

On the Gregorian calendar, the Northward equinox can occur as early as 19 March or as late as 21 March at Greenwich. For a common year the computed time slippage is about 5 hours 49 minutes later than the previous year, and for a leap year about 18 hours 11 minutes earlier than the previous year. Balancing the increases of the common years against the losses of the leap years keeps the calendar date of the March equinox from drifting more than one day from 20 March each year.

The March equinox may be taken to mark the beginning of spring and the end of winter in the Northern Hemisphere but marks the beginning of autumn and the end of summer in the Southern Hemisphere.[8]

In astronomy, the March equinox is the zero point of sidereal time and, consequently, right ascension.[9] It also serves as a reference for calendars and celebrations in many human cultures and religions.

Constellation

The point where the Sun crosses the celestial equator northwards is called the First Point of Aries. However, due to the precession of the equinoxes, this point is no longer in the constellation Aries, but rather in Pisces. By the year 2600 it will be in Aquarius. The Earth's axis causes the First Point of Aries to travel westwards across the sky at a rate of roughly one degree every 72 years. Based on the modern constellation boundaries, the northward equinox passed from Taurus into Aries in the year −1865 (1866 BC), passed into Pisces in the year −67 (68 BC), will pass into Aquarius in the year 2597, and will pass into Capricornus in the year 4312. It passed by (but not into) a 'corner' of Cetus at 0°10′ distance in the year 1489.

Apparent movement of the Sun

In its apparent motion on the day of an equinox, the Sun's disk crosses the Earth's horizon directly to the east at sunrise; and again, some 12 hours later, directly to the west at sunset. The March equinox, like all equinoxes, is characterized by having an almost exactly equal amount of daylight and night across most latitudes on Earth.[10]

Due to refraction of light rays in the Earth's atmosphere, the Sun will be visible above the horizon even when its disc is completely below the limb of the Earth. Additionally, when seen from the Earth, the Sun is a bright disc in the sky and not just a point of light, thus sunrise and sunset can be said to start several minutes before the sun's geometric center even crosses the horizon, and extends equally long after. These conditions produce differentials of actual durations of light and darkness at various locations on Earth during an equinox. This is most notable at the more extreme latitudes, where the Sun may be seen to travel sideways considerably during the morning and evening, drawing out the transition from day to night. At the north and south poles, the Sun appears to move steadily around the horizon, and just above the horizon, neither rising nor setting apart from a slight change in declination of about 0.39° per day as the equinox passes.[11]

Culture

Calendars

The Babylonian calendar began with the first new moon after the March equinox, the day after the Sumerian goddess Inanna's return from the underworld (later known as Ishtar), in the Akitu ceremony, with parades through the Ishtar Gate to the Eanna temple, and the ritual re-enactment of the marriage to Tammuz, or Sumerian Dummuzi.

The Persian calendar begins each year at the northward equinox, observationally determined at Tehran.[12]

The Indian national calendar starts the year on the day next to the vernal equinox on 22 March (21 March in leap years) with a 30-day month (31 days in leap years), then has 5 months of 31 days followed by 6 months of 30 days.[12]

Julian calendar

The Julian calendar reform lengthened seven months and replaced the intercalary month with an intercalary day to be added every four years to February. It was based on a length for the year of 365 days and 6 hours (365.25 d), while the mean tropical year is about 11 minutes and 15 seconds less than that. This had the effect of adding about three quarters of an hour every four years. The effect accumulated from inception in 45 BC until the 16th century, when the northern vernal equinox fell on 10 or 11 March.[13]

The date in 1452 was 11 March, 11:52 (Julian)[14] In 2547 it will be 20 March, 21:18 (Gregorian) and 3 March, 21:18 (Julian).[15]

Commemorations

Abrahamic tradition

- The Jewish Passover usually falls on the first full moon after the northern hemisphere vernal equinox, although occasionally (currently three times every 19 years) it will occur on the second full moon.[16]

- The Christian Churches calculate Easter as the first Sunday after the first full moon on or after the March equinox. The official church definition for the equinox is 21 March. The Eastern Orthodox Churches use the older Julian calendar, while the western churches use the Gregorian calendar, and the western full moons currently fall four, five or 34 days before the eastern ones. The result is that the two Easters generally fall on different days but they sometimes coincide. The earliest possible western Easter date in any year is 22 March on each calendar. The latest possible western Easter date in any year is 25 April.[17]

Iranian tradition

- The northward equinox marks the first day of various calendars including the Iranian calendar. The ancient Iranian peoples new year's festival of Nowruz can be celebrated 20 March or 21 March. According to the ancient Persian mythology Jamshid, the mythological king of Persia, ascended to the throne on this day and each year this is commemorated with festivities for two weeks. Along with Iranian peoples, it is also a holiday celebrated by Turkic people, the North Caucasus and in Albania. It is also a holiday for Zoroastrians, adherents of the Bahá'í Faith and Nizari Ismaili Muslims irrespective of ethnicity.[18]

West Asia and North Africa

- In many Arab countries, Mother's Day is celebrated on the northward equinox.

- Sham el-Nessim was an ancient Egyptian holiday which can be traced back as far as 2700 BC. It is still one of the public holidays in Egypt. Sometime during Egypt's Christian period (c. 200–639) the date moved to Easter Monday, but before then it coincided with the vernal equinox.

South and Southeast Asia

According to the sidereal solar calendar, celebrations which originally coincided with the March equinox now take place throughout South Asia and parts of Southeast Asia on the day when the Sun enters the sidereal Aries, generally around 14 April.

East Asia

- The traditional East Asian calendars divide a year into 24 solar terms (节气, literally "climatic segments"), and the vernal equinox (Chūnfēn, Chinese and Japanese: 春分; Korean: 춘분; Vietnamese: Xuân phân) marks the middle of the spring. In this context, the Chinese character 分 means "(equal) division" (within a season).

- In Japan, Vernal Equinox Day (春分の日 Shunbun no hi) is an official national holiday, and is spent visiting family graves and holding family reunions.[19][20] Higan (お彼岸) is a Buddhist holiday exclusively celebrated by Japanese sects during both the Spring and Autumnal Equinox.[19]

Europe

- Lieldienas

- in Norse paganism, a Dísablót was celebrated on the vernal equinox.[21]

- Drowning of Marzanna

The Americas

- Spring equinox in Teotihuacán

- The reconstructed Cahokia Woodhenge, a large timber circle located at the Mississippian culture Cahokia archaeological site near Collinsville, Illinois,[22] is the site of annual equinox and solstice sunrise observances. Out of respect for Native American beliefs these events do not feature ceremonies or rituals of any kind.[23][24][25]

Modern culture

- World Storytelling Day is a global celebration of the art of oral storytelling, celebrated every year on the day of the northward equinox.

- World Citizen Day occurs on the northward equinox.[26]

- The Bahá'í calendar year starts at the sunset preceding the March equinox calculated for Tehran.[27]

- In Annapolis, Maryland in the United States, boatyard employees and sailboat owners celebrate the spring equinox with the Burning of the Socks festival. Traditionally, the boating community wears socks only during the winter. These are burned at the approach of warmer weather, which brings more customers and work to the area. Officially, nobody then wears socks until the next equinox.[28][29]

- Neopagans observe the March equinox as a cardinal point on the Wheel of the Year. In the northern hemisphere some varieties of paganism adapt vernal equinox celebrations, while in the southern hemisphere pagans adapt autumnal traditions.

- International Astrology Day

- On 20 March 2014 and 20 March 2018, the March equinox was commemorated by an animated Google Doodle.[30]

See also

- September equinox

- June solstice

- December solstice

References

- United States Naval Observatory (4 January 2018). "Earth's Seasons and Apsides: Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion, and Aphelion". Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Astro Pixels (20 February 2018). "Solstices and Equinoxes: 2001 to 2100". Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- Serway, Raymond; Jewett, John (8 January 2013). Physics for Scientists and Engineers. Cengage Learning. p. 409. ISBN 978-1-285-53187-8.

- United States Naval Training Command (1972). Navigation compendium. U.S. Govt. Print. Off. p. 88.

- Bromberg, Irv (18 May 2012). "Churches take March 21st as the Ecclesiastical Vernal Equinox in calculating the date of Easter. This page takes an astronomical look at the equinox and March 21st". University of Toronto.

- Teaching Science. Australian Science Teachers Association. 2008.

- Desonie, Dana (2008). Polar Regions: Human Impacts. Infobase Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4381-0569-7.

- "Defining Seasons". timeanddate.com.

- Zeilik, M.; Gregory, S. A. (1998). Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics (4th ed.). Saunders College Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 0030062284.

- Resnick, Brian (19 March 2020). "The spring equinox is Thursday: 8 things to know about the first day of spring". Vox. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Bromberg, Irv. "Solar Year Length Variations" (PDF). University of Toronto, Canada.

- Bromberg, Irv. "The Lengths of the Seasons". University of Toronto, Canada. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Blackburn, Bonnie; Holford-Strevens, Leofranc (2003). The Oxford companion to the Year: An exploration of calendar customs and time-reckoning. Oxford University Press. p. 683. ISBN 0-19-214231-3. Corrected reprinting of original 1999 edition.

- Smith, Ivan (10 May 2002). "Vernal Equinox, 1452–1811". Ns1763.ca. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Smith, Ivan (10 May 2002). "Vernal Equinox, 2188–2547". Ns1763.ca. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. (1835). The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Knight. OCLC 220404854.

- Cooley, Keith (2001). "Keith's Moon Facts". Hiwaay.net personal pages.

- "Navroz". The Ismaili. Islamic Publications Limited. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Milton Walter Meyer (1993). Japan: A Concise History. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 246. ISBN 978-0-8226-3018-0.

- Yoneyuki Sugita (18 August 2016). Social Commentary on State and Society in Modern Japan. Springer. p. 23. ISBN 978-981-10-2395-8.

- "Disablót". Nationalencyklopedin (in Swedish).

- "Visitors Guide to the Woodhenge". Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Iseminger, William. "Welcome the Fall Equinox at Cahokia Mounds". Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Winter Solstice Sunrise Observance at Cahokia Mounds". Collinsville Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Cahokia Mounds Mark Spring Equinox : The keepers of Cahokia Mounds will host a spring gathering to celebrate the vernal equinox". Indian Country Today. Indian Country Media Network. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "World Citizens Day—World Unity Day". Consultative Assembly of the Peoples Congress. 2007.

- "With Spring comes the Baha'i New Year". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the United States. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- "Annapolis Welcomes Spring by Burning Socks". First Coast News.

- Rey, Diane. "Hillsmere Joins in Sock Burning Tradition". The Capital. Annapolis, Maryland. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Gander, Kashmira (20 March 2014). "Spring equinox 2014: First day of spring marked by Google Doodle". The Independent. London. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

External links

- "Ancient Equinox Alignment". Loughcrew, Ireland.

- Dates and times of the Northward equinox at the Wayback Machine (archived 10 June 2019)