Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豐臣 秀吉/豊臣 秀吉, 17 March 1537 – 18 September 1598) was a Japanese daimyō and politician of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.[1][2]

Toyotomi Hideyoshi | |

|---|---|

豐臣秀吉 | |

| |

| Imperial Regent of Japan | |

| In office August 6, 1585 – February 10, 1592 | |

| Monarch |

|

| Preceded by | Nijō Akizane |

| Succeeded by | Toyotomi Hidetsugu |

| Chancellor of the Realm | |

| In office February 2, 1586 – September 18, 1598 | |

| Monarch | Go-Yōzei |

| Preceded by | Konoe Sakihisa |

| Succeeded by | Tokugawa Ieyasu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiyoshi-maru (日吉丸) March 17, 1537 Nakamura, Owari, Japan |

| Died | September 18, 1598 (aged 61) Fushimi Castle, Kyoto, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

| Mother | Ōmandokoro |

| Father | Kinoshita Yaemon |

| Relatives |

|

| Religion | Shinto |

| Other names |

|

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Rank | Daimyō |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | see below |

Hideyoshi rose from a peasant background as a retainer of the prominent lord Oda Nobunaga to become one of the most powerful men in Japan. Hideyoshi succeeded Nobunaga after the Honnō-ji Incident in 1582 and continued Nobunaga's campaign to unite Japan that led to the closing of the Sengoku period. Hideyoshi became the de facto leader of Japan and acquired the prestigious positions of Chancellor of the Realm and Imperial Regent by the mid-1580s. Hideyoshi launched the Japanese invasions of Korea in 1592 to initial success, but eventual military stalemate damaged his prestige before his death in 1598. Hideyoshi's young son and successor Toyotomi Hideyori was displaced by Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 and would lead to the founding of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

Hideyoshi's rule covers most of the Azuchi–Momoyama period of Japan, partially named after his castle, Momoyama Castle. Hideyoshi left an influential and lasting legacy in Japan, including Osaka Castle, the Tokugawa class system, the restriction on the possession of weapons to the samurai, and the construction and restoration of many temples some of which are still visible in Kyoto.

Early life

Very little is known for certain about Toyotomi Hideyoshi before 1570, when he begins to appear in surviving documents and letters. His autobiography starts in 1577, but in it, Hideyoshi spoke very little about his past.

According to tradition, Hideyoshi was born on 17 March 1537 in Nakamura, Owari Province (present-day Nakamura Ward, Nagoya), in the middle of the chaotic Sengoku period under the collapsed Ashikaga Shogunate. Hideyoshi had no traceable samurai lineage, and his father Yaemon was an ashigaru – a peasant employed by the samurai as a foot soldier.[3] Hideyoshi had no surname, and his childhood given name was Hiyoshi-maru (日吉丸) ("Bounty of the Sun") although variations exist. Yaemon died in 1543 when Hideyoshi was 7-years-old, the younger of two children, his sibling being an older sister.[4]

Many legends describe Hideyoshi being sent to study at a temple as a young man, but he rejected temple life and went in search of adventure.[5] Under the name Kinoshita Tōkichirō (木下 藤吉郎), he first joined the Imagawa clan as a servant to a local ruler named Matsushita Yukitsuna (松下之綱). Hideyoshi traveled all the way to the lands of Imagawa Yoshimoto, the daimyō (feudal lord) based in Suruga Province, and served there for a time, only to abscond with a sum of money entrusted to him by Matsushita Yukitsuna.

Service under Nobunaga

Battle of Okehazama

In 1558, Hideyoshi became an ashigaru for the powerful Oda clan, the rulers of his home province of Owari, now headed by the ambitious Oda Nobunaga.[5] Hideyoshi soon became one of Nobunaga's sandal-bearers, a position of relatively high status, and was present at the Battle of Okehazama in 1560 when Nobunaga defeated Imagawa Yoshimoto to become one of the most powerful warlords in the Sengoku period. According to his biographers, Hideyoshi supervised the repair of Kiyosu Castle, a claim described as "apocryphal", and managed the kitchen.[6]

In 1561, Hideyoshi married One, the adopted daughter of Asano Nagakatsu. Hideyoshi carried out repairs on Sunomata Castle with his younger brother Toyotomi Hidenaga, Hachisuka Masakatsu, and Maeno Nagayasu. Hideyoshi's efforts were well-received because Sunomata was in enemy territory, and according to legend constructed a fort in Sunomata overnight and discovered a secret route into Mount Inaba, after which much of the local garrison surrendered.[7]

Siege of Inabayama Castle

Hideyoshi was very successful as a negotiator. In 1564, he managed to convince, mostly with liberal bribes, a number of Mino warlords to desert the Saitō clan. Hideyoshi approached many Saitō clan samurai and convinced them to submit to Nobunaga, including the Saitō clan's strategist, Takenaka Shigeharu.

Nobunaga's easy victory at the Siege of Inabayama Castle in 1567 was largely due to Hideyoshi's efforts,[8] and despite his peasant origins, Hideyoshi became one of Nobunaga's most distinguished generals, eventually taking the name Hashiba Hideyoshi (羽柴 秀吉). The new surname included two characters, one each from Oda's two other right-hand men, Niwa Nagahide (丹羽 長秀) and Shibata Katsuie (柴田 勝家).

Battle of Anegawa

Hideyoshi led troops in the Battle of Anegawa in 1570 in which Oda Nobunaga allied with Tokugawa Ieyasu to lay siege to two fortresses of the Azai and Asakura clans.[6][9] Hideyoshi participated in the 1573 Siege of Nagashima.[10] In 1573, after victorious campaigns against the Azai and Asakura, Nobunaga appointed Hideyoshi daimyō of three districts in the northern part of Ōmi Province. Initially, Hideyoshi based at the former Azai headquarters at Odani Castle but moved to Kunitomo and renamed the city "Nagahama" in tribute to Nobunaga. Hideyoshi later moved to the port at Imahama on Lake Biwa, where he began work on Imahama Castle and took control of the nearby Kunitomo firearms factory that had been established some years previously by the Azai and Asakura. Under Hideyoshi's administration, the factory's output of firearms increased dramatically.[11]

Hideyoshi fought in the Battle of Nagashino.[12] Nobunaga sent Hideyoshi to Himeji Castle to conquer the Chūgoku region from the Mori clan in 1576. Hideyoshi then fought in the 1577 Battle of Tedorigawa, the Siege of Miki, the Siege of Itami (1579), and the 1582 Siege of Takamatsu.[10]

Rise to power

Battle of Yamazaki and conflict with Katsuie

After the assassinations at Honnō-ji of Oda Nobunaga and his eldest son Nobutada in 1582 at the hands of Akechi Mitsuhide, Hideyoshi, seeking vengeance for the death of his beloved lord, made peace with the Mōri clan and defeated Akechi at the Battle of Yamazaki.[10]:275–279

Subsequently, Hideyoshi was in a very strong position. He summoned the powerful daimyo to Kiyosu so that they could determine Nobunaga's heir. Oda Nobukatsu and Oda Nobutaka quarreled, causing Hideyoshi to instead choose Samboshi, Nobunaga's grandson.[13] Having won the support of the other two Oda elders, Niwa Nagahide and Ikeda Tsuneoki, Hideyoshi established Hidenobu's position, as well as his own influence in the Oda clan. He distributed Nobunaga's provinces among the generals and formed a council of four generals to help govern. Tension quickly escalated between Hideyoshi and Katsuie, and at the Battle of Shizugatake in the following year, Hideyoshi destroyed Katsuie's forces.[14] Hideyoshi had thus consolidated his own power, dealt with most of the Oda clan, and controlled 30 provinces.[8]:313–314 The famous kirishitan daimyō and samurai Dom Justo Takayama fought on his side at this epic battle.

Construction of Osaka Castle

In 1582, Hideyoshi began construction of Osaka Castle. Built on the site of the temple Ishiyama Hongan-ji destroyed by Nobunaga,[15] the castle would become the last stronghold of the Toyotomi clan after Hideyoshi's death.

Battle of Komaki and Nagakute

Nobunaga's other son, Oda Nobukatsu, remained hostile to Hideyoshi. He allied himself with Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the two sides fought at the inconclusive Battle of Komaki and Nagakute. It ultimately resulted in a stalemate, although Hideyoshi's forces were delivered a heavy blow.[7] Finally, Hideyoshi made peace with Nobukatsu, ending the pretext for war between the Tokugawa and Hashiba clans. Hideyoshi sent Tokugawa Ieyasu his younger sister Asahi no kata and mother Ōmandokoro as hostages. Ieyasu eventually agreed to become a vassal of Hideyoshi.

Pinnacle of power

Like Nobunaga before him, Hideyoshi never achieved the title of shōgun. Instead, he arranged to have himself adopted by Konoe Sakihisa, one of the noblest men belonging to the Fujiwara clan and secured a succession of high court titles including, in 1585, the prestigious position of Imperial Regent (kampaku).[18] In 1586, Hideyoshi was formally given the new clan name Toyotomi (instead of Fujiwara) by the Imperial court.[7] He built a lavish palace, the Jurakudai, in 1587 and entertained the reigning Emperor, Emperor Go-Yōzei, the following year.[19]

Unified Japan

Afterwards, Hideyoshi subjugated Kii Province[20] and conquered Shikoku under the Chōsokabe clan.[21] He also took control of Etchū Province[22] and conquered Kyūshū.[23] In 1587, Hideyoshi banished Christian missionaries from Kyūshū to exert greater control over the Kirishitan daimyōs.[24] However, since he made much of trade with Europeans, individual Christians were overlooked unofficially.

In 1588, Hideyoshi forbade ordinary peasants from owning weapons and started a sword hunt to confiscate arms.[25] The swords were melted down to create a statue of the Buddha. This measure effectively stopped peasant revolts and ensured greater stability at the expense of freedom of the individual daimyōs.

Siege of Odawara

The 1590 Siege of Odawara against the Hōjō clan in the Kantō region[26] eliminated the last resistance to Hideyoshi's authority. His victory signified the end of the Sengoku period. During this siege, Hideyoshi offered Ieyasu the eight Hōjō-ruled provinces in the Kantō region in exchange for the submission of Ieyasu's five provinces. Ieyasu accepted this proposal.

Death of Sen no Rikyū

In February 1591, Hideyoshi ordered Sen no Rikyū to commit suicide, likely in one of his angry outbursts.[27] Rikyū had been a trusted retainer and master of the tea ceremony under both Hideyoshi and Nobunaga. Under Hideyoshi's patronage, Rikyū made significant changes to the aesthetics of the tea ceremony that had a lasting influence over many aspects of Japanese culture. Even after Rikyū's death, Hideyoshi is said to have built his many construction projects based upon aesthetics promoted by Rikyū, perhaps suggesting that he regretted his actions.

Following Rikyū's death, Hideyoshi turned his attention from tea ceremony to Noh, which he had been studying since becoming Imperial Regent. During his brief stay in Nagoya Castle in what is today Saga Prefecture, on Kyūshū, Hideyoshi memorized the shite (lead roles) parts of ten Noh plays, which he then performed, forcing various daimyōs to accompany him onstage as the waki (secondary, accompanying role). He even performed before the emperor.[28]

Decline of power

The stability of the Toyotomi dynasty after Hideyoshi's death was put in doubt with the death of his son Tsurumatsu in September 1591. The three-year-old was his only child. When his half-brother Hidenaga died shortly after, Hideyoshi named his nephew Hidetsugu his heir, adopting him in January 1592. Hideyoshi resigned as kampaku to take the title of taikō (retired regent). Hidetsugu succeeded him as kampaku.

With Hideyoshi's health beginning to falter, but still yearning for some accomplishment to solidify his legacy, he adopted Oda Nobunaga's dream of a Japanese conquest of China and launched the conquest of the Ming dynasty by way of Korea (at the time known as Koryu or Joseon).[29]

Hideyoshi had been communicating with the Koreans since 1587 requesting unmolested passage into China. As an ally of Ming China, the Joseon government of the time at first refused talks entirely, and in April and July 1591 also refused demands that Japanese troops be allowed to march through Korea. The government of Joseon was concerned that allowing Japanese troops to march through Korea (Joseon) would mean that masses of Ming Chinese troops would battle Hideyoshi's troops on Korean soil before they could reach China, putting Korean security at risk. In August 1591, Hideyoshi ordered preparations for an invasion of Korea to begin.

First campaign against Korea

In the first campaign, Hideyoshi appointed Ukita Hideie as field marshal, and had him go to the Korean peninsula in April 1592. Konishi Yukinaga occupied Seoul, which had been the capital of the Joseon dynasty of Korea, on June 19. After Seoul fell easily, Japanese commanders held a war council in June in Seoul and determined targets of subjugation called Hachidokuniwari (literally, dividing the country into eight routes) by each corps (the First Division of Konishi Yukinaga and others from Pyeongan Province, the Second Division of Katō Kiyomasa and others from Hangyong Province, the Third Division of Kuroda Nagamasa and others from Hwanghae Province, the Fourth Division of Mōri Yoshinari and others from Gangwon Province; the Fifth Division of Fukushima Masanori and others from Chungcheong Province; the Sixth Division by Kobayakawa Takakage and others from Jeolla Province, the Seventh Division by Mōri Terumoto and others from Gyeongsang Province, and the Eighth Division of Ukita Hideie and others from Gyeonggi Province). In only four months, Hideyoshi's forces had a route into Manchuria and occupied much of Korea. The Korean king Seonjo of Joseon escaped to Uiju and requested military intervention from China. In 1593, the Wanli Emperor of Ming China sent an army under general Li Rusong to block the planned Japanese invasion of China and recapture the Korean peninsula. The Ming army of 43,000 soldiers headed by Li Ru-song proceeded to attack Pyongyang. On January 7, 1593, the Ming relief forces under Li recaptured Pyongyang and surrounded Seoul, but Kobayakawa Takakage, Ukita Hideie, Tachibana Muneshige and Kikkawa Hiroie won the Battle of Byeokjegwan in the suburbs of Seoul. At the end of the first campaign, Japan's entire navy was destroyed by Admiral Yi Sun-sin of Korea whose base was located in a part of Korea the Japanese could not control. This, in effect, put an end to Japan's dream of conquering China as the Koreans simply destroyed Japan's ability to re-supply their troops who were bogged down in Pyongyang.

Succession dispute

The birth of Hideyoshi's second son in 1593, Hideyori, created a potential succession problem. To avoid it, Hideyoshi exiled his nephew and heir Hidetsugu to Mount Kōya and then ordered him to commit suicide in August 1595. Hidetsugu's family members who did not follow his example were then murdered in Kyoto, including 31 women and several children.[30]

Twenty-six martyrs of Japan

In January 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi had twenty-six Christians arrested as an example to Japanese who wanted to convert to Christianity. They are known as the Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan. They included five European Franciscan missionaries, one Mexican Franciscan missionary, three Japanese Jesuits and seventeen Japanese laymen including three young boys. They were tortured, mutilated, and paraded through towns across Japan. On February 5, they were executed in Nagasaki by public crucifixion.[31]

Second campaign against Korea

After several years of negotiations (broken off because envoys of both sides falsely reported to their masters that the opposition had surrendered), Hideyoshi appointed Kobayakawa Hideaki to lead a renewed invasion of Korea, but their efforts on the peninsula met with less success than the first invasion. Japanese troops remained pinned down in Gyeongsang Province. In June 1598, the Japanese forces turned back several Chinese offensives in Suncheon and Sacheon, but they were unable to make further progress as the Ming army prepared for a final assault. While Hideyoshi's battle at Sacheon was a major Japanese victory, all three parties to the war were exhausted. He told his commander in Korea, "Don't let my soldiers become spirits in a foreign land."[2]

Death

Toyotomi Hideyoshi died on September 18, 1598. He was delirious, with Sansom asserting that he was babbling of the distribution of fiefs. His last words, delivered to his closest daimyos and generals, were ''‘I depend upon you for everything. I have no other thoughts to leave behind. It is sad to part from you''. His death was kept secret by the Council of Five Elders to preserve morale, and the Japanese forces in Korea were ordered to withdraw back to Japan by the Council of Five Elders (Tokugawa Ieyasu, Maeda Toshiie, Uesugi Kakekatsu, Mori Terumoto, Ukita Hideie). Because of his failure to capture Korea, Hideyoshi's forces were unable to invade China. Rather than strengthen his position, the military expeditions left his clan's coffers and fighting strength depleted, his vassals at odds over responsibility for the failure, and the clans that were loyal to the Toyotomi name weakened. The dream of a Japanese conquest of China was put on hold indefinitely. The Tokugawa government later not only prohibited any further military expeditions to the Asian mainland but closed Japan to nearly all foreigners during the years of the Tokugawa shogunate. It was not until the late 19th century that Japan again fought a war against China through Korea, using much the same route that Hideyoshi's invasion force had used.

After his death, the other members of the Council of Five Regents were unable to keep the ambitions of Tokugawa Ieyasu in check. Two of Hideyoshi's top generals, Katō Kiyomasa and Fukushima Masanori, had fought bravely during the war but returned to find the Toyotomi clan castellan Ishida Mitsunari in power. He held the generals in contempt, and they sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu. Hideyoshi's underage son and designated successor Hideyori lost the power his father once held, and Tokugawa Ieyasu was declared shōgun following the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

Family

- Father: Kinoshita Yaemon (d. 1543)

- Mother: Ōmandokoro (1513–1592)

- Adopted father: Konoe Sakihisa

- Siblings:

- Toyotomi Hidenaga

- Tomo, married Soeda Jinbae

- Asahi no kata

Wives and concubines

- Nene, or One, later Kōdai-in. Wife.

- Yodo-dono, or Chacha, later Daikōin, daughter of Azai Nagamasa

- Minami-dono, daughter of Yamana Toyokuni

- Minami no Tsubone, daughter of Yamana Toyokuni

- Matsu no Maru-dono or Kyōgoku Tatsuko, daughter of Kyōgoku Takayoshi

- Kaga-dono or Maahime, daughter of Maeda Toshiie

- Kaihime, daughter of Narita Ujinaga

- Kusu no Tsubone later Hokoin, daughter of Azai Nagamasa

- Sonnomaru-dono, daughter of Oda Nobunaga

- Sanjo-dono or Tora, daughter of Gamō Katahide

- Himeji-dono, daughter of Oda Nobukane

- Hirozawa no Tsubone, daughter of Kunimitsu Kyosho

- Ōshima or Shimako later Gekkein, daughter of Ashikaga Yorizumi

- Anrunkin or Otane no Kata

- Ofuku later Enyu-in, daughter of Miura Noto no Kami and mother of Ukita Hideie

Children

- Hashiba Hidekatsu (Ishimatsumaru) (1570–1576) by Minami-dono

- daughter

- Toyotomi Tsurumatsu (1589–1591) by Yodo-dono

- Toyotomi Hideyori by Yodo-dono

Adopted sons

- Hashiba Hidekatsu (Tsugaru), fourth son of Oda Nobunaga

- Oda Nobutaka later Toyotomi Takahiro (1576–1602), seventh son of Oda Nobunaga

- Oda Nobuyoshi later Toyotomi Musashi more (1573–1615), eight son of Oda Nobunaga

- Oda Nobuyoshi (d. 1609), tenth son of Oda Nobunaga

- Ukita Hideie, son of Ukita Naoie

- Toyotomi Hidetsugu, first son of Hideyoshi's sister, Tomo with Miyoshi Kazumichi

- Toyotomi Hidekatsu (1569–1592), second son of Hideyoshi's sister, Tomo with Miyoshi Kazumichi

- Toyotomi Hideyasu (1579–1595), Third son of Hideyoshi's sister, Tomo with Miyoshi Kazumichi

- Yūki Hideyasu, Tokugawa Ieyasu's second son

- Ikeda Nagayoshi, third son of Ikeda Nobuteru

- Kobayakawa Hideaki, Hideyoshi's nephew from his wife, Nene

- Prince Hachijō Toshihito, sixth son of Prince Masahito

Adopted daughters

- Gohime (1574–1634), daughter of Maeda Toshiie and married Ukita Hideie

- O-hime (1585–1591), daughter of Oda Nobukatsu and married Tokugawa Hidetada

- Oeyo, daughter of Azai Nagamasa and married Saji Kazunari, Toyotomi Hidekatsu, Tokugawa Hidetada

- Konoe Sakiko, daughter of Konoe Sakihisa and married Emperor Go-Yōzei

- Chikurin-in, daughter of Ōtani Yoshitsugu and married to Sanada Yukimura. They had two sons, Sanada Daisuke and Sanada Daihachi, and some daughters. Known as Akihime and Riyohime

- Toyotomi Sadako (1592–1658), daughter of Toyotomi Hidekatsu with Oeyo later become the adopted daughter of Tokugawa Hidetada and married Kujō Yukiie

- Daizen-in, daughter of Toyotomi Hidenaga and married Mōri Hidemoto

- Kikuhime, daughter of Toyotomi Hidenaga and married Toyotomi Hideyasu

- Maeda Kikuhime (1578-1584), daughter of Maeda Toshiie

Grandchildren

- Toyotomi Kunimatsu

- Tenshuni (天秀尼) (1609–1645)

Cultural legacy

Toyotomi Hideyoshi changed Japanese society in many ways. These include the imposition of a rigid class structure, restriction on travel, and surveys of land and production.

Class reforms affected commoners and warriors. During the Sengoku period, it had become common for peasants to become warriors, or for samurai to farm due to the constant uncertainty caused by the lack of centralized government and always tentative peace. Upon taking control, Hideyoshi decreed that all peasants be disarmed completely.[32] Conversely, he required samurai to leave the land and take up residence in the castle towns.[33][34] This solidified the social class system for the next 300 years.

Furthermore, he ordered comprehensive surveys and a complete census of Japan. Once this was done and all citizens were registered, he required all Japanese to stay in their respective han (fiefs) unless they obtained official permission to go elsewhere. This ensured order in a period when bandits still roamed the countryside and peace was still new. The land surveys formed the basis for systematic taxation.[35]

In 1590, Hideyoshi completed construction of the Osaka Castle, the largest and most formidable in all Japan, to guard the western approaches to Kyoto. In that same year, Hideyoshi banned "unfree labour" or slavery,[36] but forms of contract and indentured labour persisted alongside the period penal codes' forced labour.[37]

Hideyoshi also influenced the material culture of Japan. He lavished time and money on the tea ceremony, collecting implements, sponsoring lavish social events, and patronizing acclaimed masters. As interest in the tea ceremony rose among the ruling class, so too did demand for fine ceramic implements, and during the course of the Korean campaigns, not only were large quantities of prized ceramic ware confiscated, many Korean artisans were forcibly relocated to Japan.[38]

Inspired by the dazzling Golden Pavilion in Kyoto, he had the Golden Tea Room constructed, which was covered with gold leaf and lined inside with red gossamer. Using this mobile innovation, he was able to practice the tea ceremony wherever he went, powerfully projecting his unrivalled power and status upon his arrival.

Politically, he set up a governmental system that balanced out the most powerful Japanese warlords (or daimyōs). A council was created to include the most influential lords. At the same time, a regent was designated to be in command.

Just before his death, Hideyoshi hoped to set up a system stable enough to survive until his son grew old enough to become the next leader.[39] A Council of Five Elders (五大老, go-tairō) was formed, consisting of the five most powerful daimyōs. Following the death of Maeda Toshiie, however, Tokugawa Ieyasu began to secure alliances, including political marriages (which had been forbidden by Hideyoshi). Eventually, the pro-Toyotomi forces fought against the Tokugawa in the Battle of Sekigahara. Ieyasu won and received the title of Seii-Tai Shōgun two years later.

Hideyoshi is commemorated at several Toyokuni Shrines scattered over Japan.

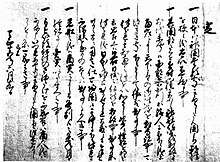

Ieyasu left in place the majority of Hideyoshi's decrees and built his shogunate upon them. This ensured that Hideyoshi's cultural legacy remained. In a letter to his wife, Hideyoshi wrote:

I mean to do glorious deeds and I am ready for a long siege, with provisions and gold and silver in plenty, so as to return in triumph and leave a great name behind me. I desire you to understand this and to tell it to everybody.[40]

Names

Because of his low birth with no family name, to the eventual achievement of Imperial Regent, the highest title of Imperial nobility, Toyotomi Hideyoshi had quite a few names throughout his life. At birth, he was given the name Hiyoshi-Maru (日吉丸). At genpuku, he took the name Kinoshita Tōkichirō (木下 藤吉郎). Later, he was given the surname Hashiba and the honorary court office Chikuzen no Kami; as a result, he was styled Hashiba Chikuzen no Kami Hideyoshi (羽柴筑前守秀吉). His surname remained Hashiba even as he was granted the new Uji or sei (氏 or 姓, clan name) Toyotomi by the Emperor.

The Toyotomi Uji was simultaneously granted to a number of Hideyoshi's chosen allies, who adopted the new Uji "豐臣朝臣/豊臣朝臣" (Toyotomi no some, courtier of Toyotomi).

The Catholic sources of the time referred to him as "emperor Taicosama" (from taikō, a retired kampaku (see Sesshō and Kampaku), and the honorific -sama).

Toyotomi Hideyoshi had been given the nickname Kozaru, meaning "little monkey", from his lord Oda Nobunaga because his facial features and skinny form resembled that of a monkey. He was also known as the "bald rat".

In popular culture

He was portrayed by Lee Hyo-jung in the 2004–2005 KBS1 TV series Immortal Admiral Yi Sun-sin.

Hyouge Mono (へうげもの, lit. "Jocular Fellow") is a Japanese manga written and illustrated by Yoshihiro Yamada. It was adapted into an anime series in 2011, and includes a fictional depiction of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's life.

In the Sengoku Basara game series and anime, he is described as a brutally strong man that killed his own wife to kill his heart, then raised an army to conquer Japan with conscripts and forced draftees.

The character “Tokeichiro” is a villain in the Onimusha video game series.

In The 39 Clues series, Toyotomi is a member of the Tomas branch of the Cahill family, the son of Thomas Cahill.

Honours

- Senior First Rank (August 18, 1915; posthumous)

See also

- People of the Sengoku period in popular culture#Toyotomi Hideyoshi

- Tokugawa Ieyasu

- Itsukushima's Senjokaku Hall

- Dom Justo Takayama

- Shogun

- Daimyo

- Samurai

Notes

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Ōmi" in Japan Encyclopedia, pp. 993–994, p. 993, at Google Books

- Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the Course of History, Viking Press 1988. p. 68.

- Berry 1982, p. 8

- Turnbull, Stephen (2010). Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 9781846039607.

- Turnbull, Stephen R. (1977). The Samurai: A Military History. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. p. 142.

- Berry 1982, p. 38

- Berry 1982, p. 179

- Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan, 1334–1615. Stanford University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0804705257.

- Turnbull, Stephen (1987). Battles of the Samurai. Arms and Armour Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0853688266.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2000). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & Co. pp. 87, 223–224, 228, 230–232. ISBN 978-1854095237.

- Berry 1982, p. 54

- Turnbull, Stephen (1977). The Samurai. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 156–160. ISBN 9780026205405.

- Berry 1982, p. 74

- Berry 1982, p. 78

- Berry 1982, p. 64

- "Kondō" (in Japanese). Hōryū-ji. Archived from the original on 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- 五重塔 (in Japanese). Hōryū-ji. Archived from the original on 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- Berry 1982, pp. 168–181

- Berry 1982, pp. 184–186

- Berry 1982, pp. 85–86

- Berry 1982, p. 83

- Berry 1982, p. 84

- Berry 1982, pp. 87–93

- Berry 1982, pp. 91–93

- Berry 1982, pp. 102–106

- Berry 1982, pp. 93–96

- Berry 1982, pp. 223–225

- Ichikawa, Danjūrō XII. Danjūrō no kabuki annai (團十郎の歌舞伎案内, "Danjūrō's Guide to Kabuki"). Tokyo: PHP Shinsho, 2008. pp. 139–140.

- Berry 1982, p. 208

- Berry 1982, pp. 217–223

- "Martyrs List". Twenty-Six Martyrs Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-02-14. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- Jansen, Marius. (2000). The Making of Modern Japan, p. 23.

- Berry 1982, pp. 106–107

- Jansen, pp. 21–22.

- Berry 1982, pp. 111–118

- Lewis, James Bryant. (2003). Frontier Contact Between Choson Korea and Tokugawa Japan, pp. 31–32.

- "Bateren-tsuiho-rei" (the Purge Directive Order to the Jesuits) Article 10

- Takeuchi, Rizō. (1985). Nihonshi shōjiten, pp. 274–275; Jansen, p. 27.

- 豊臣秀吉の遺言状 Archived 2008-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Sansom, George. (1943). Japan. A Short Cultural History, p. 410.

References

- Berry, Mary Elizabeth. (1982). Hideyoshi. Cambridge: Harvard UP, ISBN 9780674390256; OCLC 8195691

- Haboush, JaHyun Kim. (2016) The Great East Asian War and the Birth of the Korean Nation (2016) excerpt

- Jansen, Marius B. (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard UP. ISBN 9780674003347; OCLC 44090600

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toyotomi Hideyoshi. |

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Konoe Sakihisa |

Kampaku 1585–1591 |

Succeeded by Toyotomi Hidetsugu |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by Fujiwara no Sakihisa |

Daijō Daijin 1585–1591 |

Succeeded by Tokugawa Ieyasu |