Eswatini

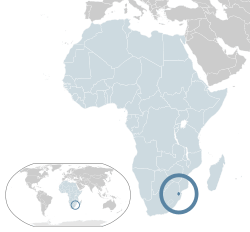

Eswatini (/ˌɛswɑːˈtiːni/ ESS-wah-TEE-nee; Swazi: eSwatini [ɛswáˈtʼiːni]), officially the Kingdom of Eswatini (Swazi: Umbuso weSwatini) and also known as Swaziland (/ˈswɑːzilænd/ SWAH-zee-land; officially renamed in 2018),[10][11] is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its north, west, and south. At no more than 200 kilometres (120 mi) north to south and 130 kilometres (81 mi) east to west, Eswatini is one of the smallest countries in Africa; despite this, its climate and topography are diverse, ranging from a cool and mountainous highveld to a hot and dry lowveld.

Kingdom of Eswatini Umbuso weSwatini (Swazi) | |

|---|---|

Flag

Coat of arms

| |

Motto: "Siyinqaba" (Swazi) "We are a fortress" "We are a mystery" "We hide ourselves away" "We are powerful ones" | |

Anthem: "Nkulunkulu Mnikati wetibusiso temaSwati" "Oh God, Bestower of the Blessings of the Swazi'" | |

| |

| |

| Capital |

26°30′S 31°30′E |

| Largest city | Mbabane |

| Official languages |

|

| Demonym(s) | Swazi |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary absolute monarchy |

• Monarch | Mswati III |

• Prime Minister | Ambrose Dlamini |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Assembly | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• Granted | 6 September 1968 |

• United Nations membership | 24 September 1968 |

• Current constitution | 2005 [1][2][3] |

| Area | |

• Total | 17,364 km2 (6,704 sq mi) (153rd) |

• Water (%) | 0.9 |

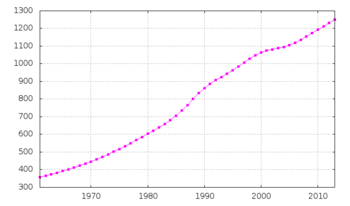

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 1,136,281[4][5] (155th) |

• 2017 census | 1,093,238[6] |

• Density | 68.2/km2 (176.6/sq mi) (135th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $12.293 billion |

• Per capita | $11,089[7] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $4.662 billion |

• Per capita | $4,145.97[7] |

| Gini (2015) | high |

| HDI (2018) | medium · 138th |

| Currency |

|

| Time zone | UTC+2 (SAST) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +268 |

| ISO 3166 code | SZ |

| Internet TLD | .sz |

Website www | |

The population is composed primarily of ethnic Swazis. The language is Swazi (siSwati in native form). The Swazis established their kingdom in the mid-18th century under the leadership of Ngwane III.[12] The country and the Swazi take their names from Mswati II, the 19th-century king under whose rule Swazi territory was expanded and unified; the present boundaries were drawn up in 1881 in the midst of the Scramble for Africa.[13] After the Second Boer War, the kingdom, under the name of Swaziland, was a British protectorate from 1903 until it regained its independence on 6 September 1968.[14] In April 2018, the official name was changed from Kingdom of Swaziland to Kingdom of Eswatini, mirroring the name commonly used in Swazi.[15][16][11]

The government is an absolute monarchy, ruled by King Mswati III since 1986.[17][18] Elections are held every five years to determine the House of Assembly and the Senate majority. The current constitution was adopted in 2005. Umhlanga, the reed dance held in August/September,[19] and incwala, the kingship dance held in December/January, are the nation's most important events.[20]

Eswatini is a developing country with a small economy. With a GDP per capita of $4,145.97, it is classified as a country with a lower-middle income.[21] As a member of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), its main local trading partner is South Africa; in order to ensure economic stability, Eswatini's currency, the lilangeni, is pegged to the South African rand. Eswatini's major overseas trading partners are the United States[22] and the European Union.[23] The majority of the country's employment is provided by its agricultural and manufacturing sectors. Eswatini is a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union, the Commonwealth of Nations, and the United Nations.

The Swazi population faces major health issues: HIV/AIDS and (to a lesser extent) tuberculosis are widespread.[24][25] It is estimated that 26% of the adult population is HIV-positive. As of 2018, Eswatini has the 12th-lowest life expectancy in the world, at 58 years.[26] The population of Eswatini is young, with a median age of 20.5 years and people aged 14 years or younger constituting 37.5% of the country's total population.[27] The present population growth rate is 1.2%.

History

Artifacts indicating human activity dating back to the early Stone Age, around 200,000 years ago, have been found in Eswatini. Prehistoric rock art paintings dating from as far back as c. 27,000 years ago, to as recent as the 19th century, can be found in various places around the country.[28]

The earliest known inhabitants of the region were Khoisan hunter-gatherers. They were largely replaced by the Nguni during the great Bantu migrations. These peoples originated from the Great Lakes regions of eastern and central Africa. Evidence of agriculture and iron use dates from about the 4th century. People speaking languages ancestral to the current Sotho and Nguni languages began settling no later than the 11th century.[29]

Swazi settlers (18th and 19th centuries)

The Swazi settlers, then known as the Ngwane (or bakaNgwane) before entering Eswatini, had been settled on the banks of the Pongola River. Before that, they were settled in the area of the Tembe River near present-day Maputo, Mozambique. Continuing conflict with the Ndwandwe people pushed them further north, with Ngwane III establishing his capital at Shiselweni at the foot of the Mhlosheni hills.[29]

Under Sobhuza I, the Ngwane people eventually established their capital at Zombodze in the heartland of present-day Eswatini. In this process, they conquered and incorporated the long-established clans of the country known to the Swazi as Emakhandzambili.[29]

Eswatini derives its name from a later king named Mswati II. KaNgwane, named for Ngwane III, is an alternative name for Eswatini, the surname of whose royal house remains Nkhosi Dlamini. Nkhosi literally means "king". Mswati II was the greatest of the fighting kings of Eswatini, and he greatly extended the area of the country to twice its current size. The Emakhandzambili clans were initially incorporated into the kingdom with wide autonomy, often including grants of special ritual and political status. The extent of their autonomy, however, was drastically curtailed by Mswati, who attacked and subdued some of them in the 1850s.[29]

With his power, Mswati greatly reduced the influence of the Emakhandzambili while incorporating more people into his kingdom either through conquest or by giving them refuge. These later arrivals became known to the Swazis as Emafikamuva. The clans who accompanied the Dlamini kings were known as the Bemdzabuko or true Swazi.

The autonomy of the Swazi nation was influenced by British and Dutch rule of southern Africa in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1881, the British government signed a convention recognising Swazi independence despite the Scramble for Africa that was taking place at the time. This independence was also recognised in the London Convention of 1884.

Because of controversial land/mineral rights and other concessions, Swaziland had a triumviral administration in 1890 following the death of King Mbandzeni in 1889. This government represented the British, the Dutch republics, and the Swazi people. In 1894, a convention placed Swaziland under the South African Republic as a protectorate. This continued under the rule of Ngwane V until the outbreak of the Second Boer War in October 1899.

King Ngwane V died in December 1899, during incwala, after the outbreak of the Second Boer War. His successor, Sobhuza II, was four months old. Swaziland was indirectly involved in the war with various skirmishes between the British and the Boers occurring in the country until 1902.

British rule over Swaziland (1906–1968)

In 1903, after the British victory in the Second Boer War, Swaziland became a British protectorate. Much of its early administration (for example, postal services) was carried out from South Africa until 1906 when the Transvaal Colony was granted self-government. Following this, Swaziland was partitioned into European and non-European (or native reserves) areas with the former being two-thirds of the total land. Sobhuza's official coronation was in December 1921 after the regency of Labotsibeni, after which he led an unsuccessful deputation to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom in London in 1922 regarding the issue of the land.[30]

In the period between 1923 and 1963, Sobhuza II established the Swazi Commercial Amadoda which was to grant licences to small businesses on the Swazi reserves and also established the Swazi National School to counter the dominance of the missions in education. His stature grew with time and the Swazi royal leadership was successful in resisting the weakening power of the British administration and the incorporation of Swaziland into the Union of South Africa.[30]

The constitution for independent Swaziland was promulgated by Britain in November 1963 under the terms of which legislative and executive councils were established. This development was opposed by the Swazi National Council (liqoqo). Despite such opposition, elections took place and the first Legislative Council of Swaziland was constituted on 9 September 1964. Changes to the original constitution proposed by the Legislative Council were accepted by Britain and a new constitution providing for a House of Assembly and Senate was drawn up. Elections under this constitution were held in 1967.

Independence (1968–present)

Following the 1967 elections, Swaziland was a protected state until independence was regained in 1968.[31]

Following the elections of 1973, the constitution of Swaziland was suspended by King Sobhuza II who thereafter ruled the country by decree until his death in 1982. At this point, Sobhuza II had ruled Swaziland for almost 83 years, making him the longest-reigning monarch in history.[32] A regency followed his death, with Queen Regent Dzeliwe Shongwe being head of state until 1984 when she was removed by the Liqoqo and replaced by Queen Mother Ntfombi Tfwala.[32] Mswati III, the son of Ntfombi, was crowned king on 25 April 1986 as King and Ingwenyama of Swaziland.[33]

The 1990s saw a rise in student and labour protests pressuring the king to introduce reforms.[34] Thus, progress toward constitutional reforms began, culminating with the introduction of the current Swazi constitution in 2005. This happened despite objections by political activists. The current constitution does not clearly deal with the status of political parties.[35]

The first election under the new constitution took place in 2008. Members of parliament were elected from 55 constituencies (also known as tinkhundla). These MPs served five-year terms which ended in 2013.[35]

In 2011, Swaziland suffered an economic crisis, due to reduced SACU receipts. This caused the government to request a loan from neighbouring South Africa. However, they did not agree with the conditions of the loan, which included political reforms.[36]

During this period, there was increased pressure on the Swazi government to carry out more reforms. Public protests by civic organisations and trade unions became more common. Starting in 2012, improvements in SACU receipts have eased the fiscal pressure on the Swazi government. A new parliament, the second since promulgation of the constitution, was elected on 20 September 2013. At this time the king reappointed Sibusiso Dlamini as prime minister for the third time.[37]

On 19 April 2018, King Mswati III announced that the Kingdom of Swaziland had renamed itself the Kingdom of Eswatini, reflecting the extant Swazi name for the state eSwatini, to mark the 50th anniversary of Swazi independence. The new name, Eswatini, means "land of the Swazis" in the Swazi language and was partially intended to prevent confusion with the similarly named Switzerland.[10][11]

Eswatini workers began anti-government protests against low salaries on 19 September 2018. They went on a three-day strike organised by the Trade Union Congress of Swaziland (TUCOSWA) that resulted in widespread disruption.[38]

Government and politics

Monarchy

Eswatini is an absolute monarchy with constitutional provision and Swazi law and customs.[39] The functional head of state is the king or Ngwenyama (lit. Lion), currently King Mswati III, who ascended to the throne in 1986 after the death of his father King Sobhuza II in 1982 and a period of regency. According to the country's constitution, the Ingwenyama is a symbol of unity and the eternity of the Swazi nation.[40]

By tradition, the king reigns along with his mother (or a ritual substitute), the Ndlovukati (lit. She-Elephant). The former was viewed as the administrative head of state and the latter as a spiritual and national head of state, with real power counterbalancing that of the king, but, during the long reign of Sobhuza II, the role of the Ndlovukati became more symbolic.

The king appoints the prime minister from the legislature and also appoints a minority of legislators to both chambers of the Libandla (parliament) with help from an advisory council. The king is allowed by the constitution to appoint some members to parliament to represent special interests. These special interests are citizens who might have been electoral candidates who were not elected, or might not have stood as candidates. This is done to balance views in parliament. Special interests could be people of particular gender or race, people of disability, the business community, civic society, scholars, and chiefs.

Parliament

The Swazi bicameral Parliament, or Libandla, consists of the Senate (30 seats; 10 members appointed by the House of Assembly and 20 appointed by the monarch; to serve five-year terms) and the House of Assembly (65 seats; 10 members appointed by the monarch and 55 elected by popular vote; to serve five-year terms). The elections are held every five years after dissolution of parliament by the king. The last elections were held on 18 August and 21 September 2018.[41][42] The balloting is done in a non-partisan manner. All election procedures are overseen by the Elections and Boundaries Commission.[43]

Political culture

At Swaziland's independence on 6 September 1968, Swaziland adopted a Westminster-style constitution. On 12 April 1973, King Sobhuza II annulled it by decree, assuming supreme powers in all executive, judicial, and legislative matters.[44] The first non-party elections for the House of Assembly were held in 1978, and they were conducted under the tinkhundla as electoral constituencies determined by the King, and established an Electoral Committee appointed by the King to supervise elections.[44]

Until the 1993 election, the ballot was not secret, voters were not registered, and they did not elect representatives directly. Instead, voters elected an electoral college by passing through a gate designated for the candidate of choice while officials counted them.[44] Later on, a constitutional review commission was appointed by King Mswati III in July 1996, comprising chiefs, political activists, and unionists to consider public submissions and draft proposals for a new constitution.[45]

Drafts were released for comment in May 1999 and November 2000. These were strongly criticised by civil society organisations in Swaziland and human rights organisations elsewhere. A 15-member team was announced in December 2001 to draft a new constitution; several members of this team were reported to be close to the royal family.[46]

In 2005, the constitution was put into effect. There is still much debate in the country about the constitutional reforms. From the early seventies, there was active resistance to the royal hegemony.

Elections

Nominations take place at the chiefdoms. On the day of nomination, the name of the nominee is raised by a show of hand and the nominee is given an opportunity to indicate whether he or she accepts the nomination. If he or she accepts it, he or she must be supported by at least ten members of that chiefdom. The nominations are for the position of Member of Parliament, Constituency Headman (Indvuna), and the Constituency Executive Committee (Bucopho). The minimum number of nominees is four and the maximum is ten.[47]

Primary elections also take place at the chiefdom level. It is by secret ballot. During the Primary Elections, the voters are given an opportunity to elect the member of the executive committee (Bucopho) for that particular chiefdom. Aspiring members of parliament and the constituency Headman are also elected from each chiefdom. The secondary and final elections takes place at the various constituencies called Tinkhundla.[47]

Candidates who won primary elections in the chiefdoms are considered nominees for the secondary elections at inkhundla or constituency level. The nominees with majority votes become the winners and they become members of parliament or constituency headman.[48][49]

Foreign relations

Eswatini is a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the African Union, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, and the Southern African Development Community.[50][51][52][53][54]

Judiciary

The judicial system in Eswatini is a dual system. The 2006 constitution established a court system based on the Western model consisting of four regional Magistrates Courts, a High Court, and a Court of Appeal (the Supreme Court), which are independent of crown control. In addition, traditional courts (Swazi Courts or Customary Courts) deal with minor offenses and violations of traditional Swazi law and custom.[55]

Judges are appointed by the King and are usually expatriates from South Africa.[56] The Supreme Court, which replaced the previous Court of Appeal, consists of the Chief Justice and at least four other Supreme Court judges. The High Court consists of the Chief Justice and at least four High Court judges.[57]

Chief Justices

Military

The military of Eswatini (Umbutfo Eswatini Defence Force) is used primarily during domestic protests, with some border and customs duties. The military has never been involved in a foreign conflict.[61] The king is the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Force and the substantive Minister of the Ministry of Defence.[62]

There are approximately 3,000 personnel in the defence force, with the army being the largest component.[63] There is a small airforce, which is mainly used for transporting the king as well as cargo and personnel, surveying land with search and rescue functions, and mobilising in case of a national emergency.[64]

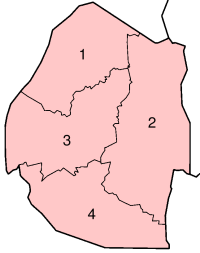

Administrative divisions

Eswatini is divided into four regions: Hhohho, Lubombo, Manzini, and Shiselweni. In each of the four regions, there are several tinkhundla (singular inkhundla). The regions are managed by a regional administrator, who is aided by elected members in each inkhundla.[65]

The local government is divided into differently structured rural and urban councils depending on the level of development in the area. Although there are different political structures to the local authorities, effectively the urban councils are municipalities and the rural councils are the tinkhundla. There are twelve municipalities and 55 tinkhundla.

There are three tiers of government in the urban areas and these are city councils, town councils and town boards. This variation considers the size of the town or city. Equally, there are three tiers in the rural areas which are the regional administration at the regional level, tinkhundla and chiefdoms. Decisions are made by full council based on recommendations made by the various sub-committees. The town clerk is the chief advisor in each local council council or town board.

There are twelve declared urban areas, comprising two city councils, three town councils and seven town boards. The main cities and towns in Eswatini are Manzini, Mbabane, Nhlangano and Siteki which are also regional capitals. The first two have city councils and the latter two have town councils. Other small towns or urban area with substantial population are Ezulwini, Matsapha, Hlatikhulu, Pigg's Peak, Simunye, and Big Bend.

As noted above, there are 55 tinkhundla in Eswatini and each elects one representative to the House of Assembly of Eswatini. Each inkhundla has a development committee (bucopho) elected from the various constituency chiefdoms in its area for a five-year term. Bucopho bring to the inkhundla all matters of interest and concern to their various chiefdoms, and take back to the chiefdoms the decisions of the inkhundla. The chairman of the bucopho is elected at the inkhundla and is called indvuna ye nkhundla.

| Region | Capital | Largest city | Area (km²) |

Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hhohho | Mbabane | Mbabane | 3,569 | 320,651 |

| Manzini | Manzini | Manzini | 5,068 | 355,945 |

| Shiselweni | Nhlangano | Nhlangano | 3,790 | 204,111 |

| Lubombo | Siteki | Siteki | 5,947 | 212,531 |

Geography

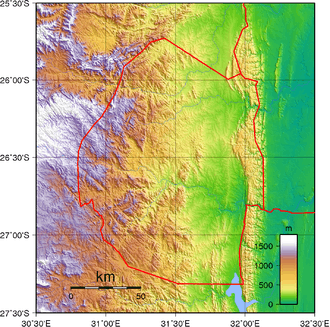

Eswatini lies across a fault which runs from the Drakensberg Mountains of Lesotho, north through the Eastern highlands of Zimbabwe, and forms the Great Rift Valley of Kenya.

A small, landlocked kingdom, Eswatini is bordered in the North, West and South by the Republic of South Africa and by Mozambique in the East. Eswatini has a land area of 17,364 km2 (6,704 sq mi). Eswatini has four separate geographical regions. These run from North to South and are determined by altitude. Eswatini is at approximately 26°30'S, 31°30'E.[66] Eswatini has a wide variety of landscapes, from the mountains along the Mozambican border to savannas in the east and rain forest in the northwest. Several rivers flow through the country, such as the Great Usutu River.

Along the eastern border with Mozambique is the Lubombo, a mountain ridge, at an altitude of around 600 metres (2,000 ft). The mountains are broken by the canyons of three rivers, the Ngwavuma, the Usutu and the Mbuluzi River. This is cattle ranching country. The western border of Eswatini, with an average altitude of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft), lies on the edge of an escarpment. Between the mountains rivers rush through deep gorges. Mbabane, the capital, is on the Highveld.

The Middleveld, lying at an average 700 metres (2,300 ft) above sea level is the most densely populated region of Eswatini with a lower rainfall than the mountains. Manzini, the principal commercial and industrial city, is situated in the Middleveld.

The Lowveld of Eswatini, at around 250 metres (820 ft), is less populated than other areas and presents a typical African bush country of thorn trees and grasslands. Development of the region was inhibited, in early days, by the scourge of malaria.

Climate

Eswatini is divided into four climatic regions: the Highveld, Middleveld, Lowveld and Lubombo plateau. The seasons are the reverse of those in the Northern Hemisphere with December being mid-summer and June mid-winter. Generally speaking, rain falls mostly during the summer months, often in the form of thunderstorms.

Winter is the dry season. Annual rainfall is highest on the Highveld in the west, between 1,000 and 2,000 mm (39.4 and 78.7 in) depending on the year. The further east, the less rain, with the Lowveld recording 500 to 900 mm (19.7 to 35.4 in) per annum.

Variations in temperature are also related to the altitude of the different regions. The Highveld temperature is temperate and seldom uncomfortably hot, while the Lowveld may record temperatures around 40 °C (104 °F) in summer.

The average temperatures at Mbabane, according to season:

| Spring | September–October | 18 °C (64.4 °F) |

| Summer | November–March | 20 °C (68 °F) |

| Autumn | April–May | 17 °C (62.6 °F) |

| Winter | June–August | 13 °C (55.4 °F) |

Climate change

Climate change in Eswatini is mainly evident in changing precipitation - including variability, persistent drought and heightened storm intensity. In turn, this leads to desertification, increased food insecurity and reduced river flows. Despite being responsible for a negligible portion of total global greenhouse gas emissions Eswatini is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The government of Eswatini has expressed concern that climate change is exacerbating existing social challenges such as poverty, a high HIV prevalence and food insecurity and will drastically restrict the country's ability to develop, as per Vision 2022.[67] Economically, climate change has already adversely impacted Eswatini. For instance, the 2015-2016 drought decreased sugar and soft drink concentrate production export (Eswatini's largest economic export). Many of Eswatini's major exports are raw, agricultural products and are therefore vulnerable to a changing climate.[68]

Wildlife

There are known to be 507 bird species in Eswatini, including 11 globally threatened species and four introduced species, and 107 mammal species endemic to Eswatini, including the critically endangered South-central black rhinoceros and seven other endangered or vulnerable species.

Protected areas of Eswatini include seven nature reserves, four frontier conservation areas and three wildlife or game reserves. Hlane Royal National Park, the largest park in Eswatini, is rich in bird life, including white-backed vultures, white-headed, lappet-faced and Cape vultures, raptors such as martial eagles, bateleurs, and long-crested eagles, and the southernmost nesting site of the marabou stork.[69]

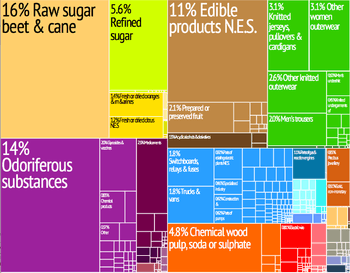

Economy

Eswatini's economy is diverse, with agriculture, forestry and mining accounting for about 13% of GDP, manufacturing (textiles and sugar-related processing) representing 37% of GDP and services – with government services in the lead – constituting 50% of GDP. Title Deed Lands (TDLs), where the bulk of high value crops are grown (sugar, forestry, and citrus) are characterised by high levels of investment and irrigation, and high productivity.

About 75% of the population is employed in subsistence agriculture upon Swazi Nation Land (SNL). In contrast with the commercial farms, Swazi Nation Land suffers from low productivity and investment. This dual nature of the Swazi economy, with high productivity in textile manufacturing and in the industrialised agricultural TDLs on the one hand, and declining productivity subsistence agriculture (on SNL) on the other, may well explain the country's overall low growth, high inequality and unemployment.

Economic growth in Eswatini has lagged behind that of its neighbours. Real GDP growth since 2001 has averaged 2.8%, nearly 2 percentage points lower than growth in other Southern African Customs Union (SACU) member countries. Low agricultural productivity in the SNLs, repeated droughts, the devastating effect of HIV/AIDS and an overly large and inefficient government sector are likely contributing factors. Eswatini's public finances deteriorated in the late 1990s following sizeable surpluses a decade earlier. A combination of declining revenues and increased spending led to significant budget deficits.

The considerable spending did not lead to more growth and did not benefit the poor. Much of the increased spending has gone to current expenditures related to wages, transfers, and subsidies. The wage bill today constitutes over 15% of GDP and 55% of total public spending; these are some of the highest levels on the African continent. The recent rapid growth in SACU revenues has, however, reversed the fiscal situation, and a sizeable surplus was recorded since 2006. SACU revenues today account for over 60% of total government revenues. On the positive side, the external debt burden has declined markedly over the last 20 years, and domestic debt is almost negligible; external debt as a percent of GDP was less than 20% in 2006.

Eswatini's economy is very closely linked to the economy of South Africa, from which it receives over 90% of its imports and to which it sends about 70% of its exports. Eswatini's other key trading partners are the United States and the EU, from whom the country has received trade preferences for apparel exports (under the African Growth and Opportunity Act – AGOA – to the US) and for sugar (to the EU). Under these agreements, both apparel and sugar exports did well, with rapid growth and a strong inflow of foreign direct investment. Textile exports grew by over 200% between 2000 and 2005 and sugar exports increasing by more than 50% over the same period.

The continued vibrancy of the export sector is threatened by the removal of trade preferences for textiles, the accession to similar preferences for East Asian countries, and the phasing out of preferential prices for sugar to the EU market. Eswatini will thus have to face the challenge of remaining competitive in a changing global environment. A crucial factor in addressing this challenge is the investment climate.

The recently concluded Investment Climate Assessment provides some positive findings in this regard, namely that Eswatini firms are among the most productive in Sub-Saharan Africa, although they are less productive than firms in the most productive middle-income countries in other regions. They compare more favourably with firms from lower middle income countries, but are hampered by inadequate governance arrangements and infrastructure.

Eswatini's currency, the lilangeni, is pegged to the South African rand, subsuming Eswatini's monetary policy to South Africa. Customs duties from the Southern African Customs Union, which may equal as much as 70% of government revenue this year, and worker remittances from South Africa substantially supplement domestically earned income. Eswatini is not poor enough to merit an IMF programme; however, the country is struggling to reduce the size of the civil service and control costs at public enterprises. The government is trying to improve the atmosphere for foreign direct investment.

Society

Demographics

The majority of Eswatini's population is ethnically Swazi, mixed with a small number of Zulu and White Africans, mostly people of British and Afrikaner descent. Traditionally Swazi have been subsistence farmers and herders, but most now mix such activities with work in the growing urban formal economy and in government. Some Swazi work in the mines in South Africa.

Eswatini also received Portuguese settlers and African refugees from Mozambique. Christianity in Eswatini is sometimes mixed with traditional beliefs and practices. Many traditionalists believe that most Swazi ascribe a special spiritual role to the monarch.

Population centres

This is a list of major cities and towns in Eswatini. The table below also includes the population and region.

| Rank | City | Census 1986 | Census 1997 | 2005 estimate | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Manzini | 46,058 | 78,734 | 110,537 | Manzini |

| 2. | Mbabane | 38,290 | 57,992 | 76,218 | Hhohho |

| 3. | Nhlangano | 4,107 | 6,540 | 9,016 | Shiselweni |

| 4. | Siteki | 2,271 | 4,157 | 6,152 | Lubombo |

Languages

SiSwati[70] (also known as Swati, Swazi or Siswati) is a Bantu language of the Nguni Group, spoken in Eswatini and South Africa. It has 2.5 million speakers and is taught in schools. It is an official language of Eswatini, along with English,[71] and one of the official languages of South Africa. English is the medium of communication in schools and in conducting business including the press.

About 76,000 people in the country speak Zulu.[72] Tsonga, which is spoken by many people throughout the region is spoken by about 19,000 people in Eswatini. Afrikaans is also spoken by some residents of Afrikaner descent. Portuguese has been introduced as a third language in the schools, due to the large community of Portuguese speakers from Mozambique or Northern and Central Portugal.[73]

Religion

Eighty-three percent of the total population adheres to Christianity in Eswatini. Anglican, Protestant and indigenous African churches, including African Zionist, constitute the majority of Christians (40%), followed by Roman Catholicism at 6% of the population. On 18 July 2012, Ellinah Wamukoya, was elected Anglican Bishop of Swaziland, becoming the first woman to be a bishop in Africa. Fifteen percent of the population follows traditional religions; other non-Christian religions practised in the country include Islam (2%[74]), the Bahá'í Faith (0.5%), and Hinduism (0.2%).[75] There were 14 Jewish families in 2013.[76]

The Kingdom of Eswatini does not recognise non-civil marriages such as Islamic-rite marriage contracts.[77]

Health

As of 2016, Eswatini has the highest prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15 to 49 in the world (27.2%).[78][79]

Education

.jpg)

Education in Eswatini begins with pre-school education for infants, primary, secondary and high school education for general education and training (GET), and universities and colleges at the tertiary level. Pre-school education is usually for children 5-year or younger; after that the students can enroll in a primary school anywhere in the country. In Eswatini early childhood care and education (ECCE) centres are in the form of preschools or neighbourhood care points (NCPs). In the country 21.6% of preschool age children have access to early childhood education.[80]

Primary education in Eswatini begins at the age of six. It is a seven-year programme that culminates with an end of Primary school Examination [SPC] in grade 7 which is a locally based assessment administered by the Examinations Council through schools. Primary Education is from grade 1 to grade 7.[81]

The secondary and high school education system in Eswatini is a five-year programme divided into three years junior secondary and two years senior secondary. There is an external public examination (Junior Certificate) at the end of the junior secondary that learners have to pass to progress to the senior secondary level. The Examinations Council of Swaziland (ECESWA) administers this examination. At the end of the senior secondary level, learners sit for a public examination, the Swaziland General Certificate of Secondary Education (SGCSE) and International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) which is accredited by the Cambridge International Examination (CIE). A few schools offer the Advanced Studies (AS) programme in their curriculum.[82]

There are 830 public schools in Eswatini including primary, secondary and high schools.[83] There are also 34 recognised private schools with an additional 14 unrecognised. The biggest number of schools is in the Hhohho region.[83] Education in Eswatini as of 2009 is free at primary level, mainly first through the fourth grade and also free for orphaned and vulnerable children, but not compulsory.[84]

In 1996, the net primary school enrollment rate was 90.8%, with gender parity at the primary level.[84] In 1998, 80.5% of children reached grade five.[84] Eswatini is home to a United World College. In 1963, Waterford School, later named Waterford Kamhlaba United World College of Southern Africa, was founded as southern Africa's first multiracial school. In 1981, Waterford Kamhlaba joined the United World Colleges movement as the first and only United World College on the African continent.

Adult and non-formal education centres are Sebenta National Institute for adult basic literacy and Emlalatini Development Centre, which provides alternative educational opportunities for school children and young adults who have not been able to complete their schooling.

Higher education

The University of Eswatini, Southern African Nazarene University and Swaziland Christian University (SCU) are the institutions that offer university education in the country. A campus of Limkokwing University of Creative Technology can be found at Sidvwashini (Sidwashini), a suburb of the capital Mbabane. Ngwane Teacher's College and William Pitcher College are the country's teaching colleges. The Good Shepherd Hospital in Siteki is home to the College for Nursing Assistants.[85][86]

The University of Eswatini is the national university, established in 1982 by act of parliament, and is headquartered at Kwaluseni with additional campuses in Mbabane and Luyengo.[87] The Southern African Nazarene University (SANU) was established in 2010 as a merger of the Nazarene College of Nursing, College of Theology and the Nazarene Teachers College; it is in Manzini next to the Raleigh Fitkin Memorial Hospital. It is the university that produce the most nurses in the country.As a University it encampasses three faculties of which one is at Siteki which is the faculty of Theology and the other Two are found in Manzini which are the faculties of Education and the faculty of health Sciences [88][89]

The SCU, focusing on medical education, was established in 2012 and is Eswatini's newest university.[90] It is in Mbabane.[91] The campus of Limkokwing University was opened at Sidvwashini in Mbabane in 2012.[92]

The main centre for technical training in Eswatini is the Swaziland College of Technology (SCOT) which is slated to become a full university.[93] It aims to provide high quality training in technology and business studies in collaboration with the commercial, industrial and public sectors.[94] Other technical and vocational institutions include the Gwamile Vocational and Commercial Training Institute in Matsapha, the Manzini Industrial and Training Centre (MITC) in Manzini, Nhlangano Agricultural Skills Training Centre, and Siteki Industrial Training Centre.

In addition to these institutions, the kingdom also has the Swaziland Institute of Management and Public Administration (SIMPA) and Institute of Development Management (IDM). SIMPA is a government-owned management and development institute and IDM is a regional organisation in Botswana, Lesotho, and Eswatini, providing training, consultancy, and research in management. North Carolina State University's Poole College of Management is a sister school of SIMPA.[95] The Mananga Management Centre was established at Ezulwini as Mananga Agricultural Management Centre in 1972 as an international management development centre offering training of middle and senior managers.[96]

Culture

The principal Swazi social unit is the homestead, a traditional beehive hut thatched with dry grass. In a polygamous homestead, each wife has her own hut and yard surrounded by reed fences. There are three structures for sleeping, cooking, and storage (brewing beer). In larger homesteads there are also structures used as bachelors' quarters and guest accommodation.

Central to the traditional homestead is the cattle byre, a circular area enclosed by large logs, interspaced with branches. The cattle byre has ritual as well as practical significance as a store of wealth and symbol of prestige. It contains sealed grain pits. Facing the cattle byre is the great hut which is occupied by the mother of the headman.

The headman is central to all homestead affairs and he is often polygamous. He leads through example and advises his wives on all social affairs of the home as well as seeing to the larger survival of the family. He also spends time socialising with the young boys, who are often his sons or close relatives, advising them on the expectations of growing up and manhood.

The Sangoma is a traditional diviner chosen by the ancestors of that particular family. The training of the Sangoma is called "kwetfwasa". At the end of the training, a graduation ceremony takes place where all the local sangoma come together for feasting and dancing. The diviner is consulted for various purposes, such as determining the cause of sickness or even death. His diagnosis is based on "kubhula", a process of communication, through trance, with the natural superpowers. The Inyanga (a medical and pharmaceutical specialist in western terms) possesses the bone throwing skill ("kushaya ematsambo") used to determine the cause of the sickness.

The most important cultural event in Eswatini is the Incwala ceremony. It is held on the fourth day after the full moon nearest the longest day, 21 December. Incwala is often translated in English as "first fruits ceremony", but the King's tasting of the new harvest is only one aspect among many in this long pageant. Incwala is best translated as "Kingship Ceremony": when there is no king, there is no Incwala. It is high treason for any other person to hold an Incwala.

Every Swazi may take part in the public parts of the Incwala. The climax of the event is the fourth day of the Big Incwala. The key figures are the King, Queen Mother, royal wives and children, the royal governors (indunas), the chiefs, the regiments, and the "bemanti" or "water people".

Eswatini's most well-known cultural event is the annual Umhlanga Reed Dance. In the eight-day ceremony, girls cut reeds and present them to the queen mother and then dance. (There is no formal competition.) It is done in late August or early September. Only childless, unmarried girls can take part. The aims of the ceremony are to preserve girls' chastity, provide tribute labour for the Queen mother, and to encourage solidarity by working together. The royal family appoints a commoner maiden to be "induna" (captain) of the girls and she announces over the radio the dates of the ceremony. She will be an expert dancer and knowledgeable on royal protocol. One of the King's daughters will be her counterpart.

The Reed Dance today is not an ancient ceremony but a development of the old "umchwasho" custom. In "umchwasho", all young girls were placed in a female age-regiment. If any girl became pregnant outside of marriage, her family paid a fine of one cow to the local chief. After a number of years, when the girls had reached a marriageable age, they would perform labour service for the Queen Mother, ending with dancing and feasting. The country was under the chastity rite of "umchwasho" until 19 August 2005.

Eswatini is also known for a strong presence in the handcrafts industry. The formalised handcraft businesses of Eswatini employ over 2,500 people, many of whom are women (per TechnoServe Swaziland Handcrafts Impact Study, February 2011). The products are unique and reflect the culture of Eswatini, ranging from housewares, to artistic decorations, to complex glass, stone, or wood artwork.

Princess Sikhanyiso Dlamini at the reed dance (umhlanga) festival

Princess Sikhanyiso Dlamini at the reed dance (umhlanga) festival A traditional Swazi homestead

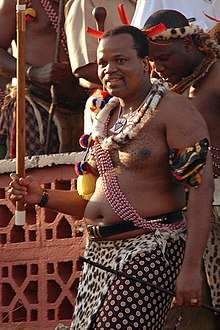

A traditional Swazi homestead Swazi warriors at the incwala ceremony

Swazi warriors at the incwala ceremony

See also

- Index of Eswatini-related articles

- Outline of Eswatini

- HIV/AIDS in Eswatini

References

- "Laws" (PDF). wipo.int. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Constitution" (PDF). gov.sz. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Swaziland Releases Population Count from 2017 Census". United Nations Population Fund. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". imf.org.

- "Swaziland – Country partnership strategy FY2015-2018". World Bank. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Swaziland king changes the country's name". BBC News. 19 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- "Kingdom of Swaziland Change Now Official". Times Of Swaziland. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Bonner, Philip (1982). Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–27. ISBN 0521242703.

- Kuper, Hilda (1986). The Swazi: A South African Kingdom. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 9–10.

- Gillis, Hugh (1999). The Kingdom of Swaziland: Studies in Political History. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313306702.

- jess (20 April 2018). "Swaziland facts and guide as the country renamed the Kingdom of eSwatini". How Dare She. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "UN Member States". United Nations. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- Tofa, Moses (16 May 2013). "Swaziland: Wither absolute monarchism?". Pambazuka News (630). Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Swaziland: Africa′s last absolute monarchy". Deutsche Welle. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Cultural Resources – Swazi Culture – The Umhlanga or Reed Dance". Swaziland National Trust Commission.

- kbraun@africaonline.co.sz. "Cultural Resources – Swazi Culture – The Incwala or Kingship Ceremony". Swaziland National Trust Commission.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". International Monetary Fund.

- "Swaziland | Office of the United States Trade Representative". Ustr.gov. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Swaziland". Comesaria.org. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Projects : Swaziland Health, HIV/AIDS and TB Project". The World Bank. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Swaziland: Dual HIV and Tuberculosis Epidemic Demands Urgent Action updated 18 November 2010

- "The Economist explains: Why is Swaziland's king renaming his country?". Economist.com. The Economist. 30 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Swaziland Demographics Profile 2013". Indexmundi.com. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- History Online, South African (2011). Swaziland. South African History Online.

- Bonner, Philip (1983). Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires: The Evolution and Dissolution of the Nineteenth-Century Swazi State. Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press. pp. 60, 85–88. ISBN 9780521523004

- Vail, Leroy (1991). The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. University of California Press. pp. 295–296. ISBN 0520074203.

- "Swaziland Independence Act 1968". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Swazi King ready to rule – after exams". Christian Science Monitor. 20 May 1986. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Mswati III, the new teenage king of Swaziland, vowed..." UPI. 26 April 1986.

- "Swaziland: Doubt over the legality of protests keep Swazis at bay, for now". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Swaziland : Constitution and politics | The Commonwealth". thecommonwealth.org. The Commonwealth. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Timeline: Swaziland economic crisis". IOL Business Report. 8 January 2013.

- "King re-appoints Dr. B.S. Dlamini as Prime Minister". Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Swaziland: Police Turn Swaziland City Into 'Warzone' As National Strike Enters Second Day". 21 September 2018 – via AllAfrica.

- "Our governance". Gov.sz. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- The Constitution of The Kingdom of Swaziland Act, 2005, Chapter 1, Section 4(2)

- "eSwatini, Formerly Swaziland, Heads for First Elections Under New Name". VOA. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Polls open in eSwatini, where king has absolute rule | DW | 21.09.2018". DW.COM. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- "Swaziland: Elections and Boundaries Commission". EISA. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Swaziland: Tinkhundla electoral system". Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- Africa South of the Sahara 2004. Psychology Press. 2003. p. 1096. ISBN 9781857431834

- Africa South of the Sahara 2004. Psychology Press. 2003. p. 1097. ISBN 9781857431834

- "Swaziland: Tinkhundla electoral system". EISA. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Conduct of elections in Swaziland" (PDF). Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Swaziland: Electoral system". EISA. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "United Nations in Swaziland". sz.one.un.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Kingdom of eSwatini | The Commonwealth". thecommonwealth.org. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Kingdom of Swaziland | African Union". au.int. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "COMESA Members States – Common Market for Eastern & Southern Africa". Common Market for Eastern & Southern Africa. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Southern African Development Community :: Eswatini". sadc.int. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Judiciary". The Government of the Kingdom of Eswatini. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "Swaziland – Judicial system". Nations Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "The Law and Legal Research in Swaziland". Hauser Global Law School Program. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "The African Parks Network: Board". Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Swaziland government re-appoints controversial chief judge". The New Age Online. 25 June 2012. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Ndzimandze, Mbongiseni (13 November 2015). "Justice Maphalala Confirmed as CJ". Times of Swaziland. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Crash diminishes Swaziland's air force". Independent Online (South Africa). 23 November 2004. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- "Swaziland: Time for Democracy?". Africafocus.org. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "SIPRI military expenditure database". Milexdata.sipri.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "Air force (Swaziland) – Sentinel Security Assessment – Southern Africa". Janes.com. 12 April 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "Country Profile: Swaziland: The local government system in Swaziland" (PDF). Commonwealth Local Government Forum. 16 May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- WorldAtlas.com, Inc. "Map of Swaziland". Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/Eswatini%20First/Eswatini%27s%20INDC.pdf Retrieved 5 March 2020

- https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/Eswatini%20First/Eswatini%27s%20INDC.pdf Retrieved 5 March 2020

- "Hlane Royal National Park". biggameparks.org. Malkerns, Swaziland: Big Game Parks. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- U.S. Department of State. "Background Note:Swaziland". Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- "The Constitution of the Kingdom of Swaziland Act, 2005" (PDF). p. 12. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Lewis, M. Paul (2009). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition". Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- "África do Sul será primeiro país não europeu com ensino complementar de língua portuguesa". IILP. 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor International Religious Freedom Report for 2015". U.S. State Department.

- Religious Intelligence. "Country Profile: Swaziland (Kingdom of Swaziland)". Archived from the original on 26 June 2008.

- Maltz, Judy (7 May 2013). "A black Swazi Jew defends his people in Hungary". Haaretz.

- Zulu, Phathizwe (26 November 2016). "Swaziland marriage law leaves Muslims in legal quagmire". Anadolu Agency. Turkey.

- "Swaziland 2016 Country factsheet". UNAIDS. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "Prevalence of HIV, total (% of population ages 15-49)". The World Bank. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- "Early Childhood & Care Education". Gov.sz. 22 September 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Primary Education". Gov.sz. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Secondary Education". Gov.sz. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Ministry of Education. "School Lists" (PDF). Swaziland Govt. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- "2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor". Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor. 2002. Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- "Programme: Good Shepherd Hospital, Siteki, Swaziland | CBM International". Cbm.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Hester Klopper (2012). The State of Nursing and Nursing Education in Africa. Sigma Theta Tau. ISBN 978-1935476849.

- "History | University of Swaziland". Uniswa.sz. 20 October 1975. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Church of the Nazarene Africa Region | Africa South". Africanazarene.org. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Southern Africa Nazarene University launched in Swaziland – Nazarene Communications Network". Ncnnews.com. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Swaziland Christian University » Our Vision and Mission". Scusz.ac. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Swaziland Christian University » Contact us". Scusz.ac. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Rooney, Richard (15 November 2012). "Swaziland: Limkokwing Reduces Minister to Tears (Page 1 of 2)". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "SCOT to become Swaziland University of Science and Technology Swaziland News". Swazilive.com. 9 November 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "SCOT welcomes you!". Scot.co.sz. Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- "Welcome To IDM". Idmbls.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Company History | Mananga Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- "Eswatini". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Swaziland from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Eswatini at Curlie

- eSwatini from the BBC News

- Key Development Forecasts for Swaziland from International Futures

- Government of Eswatini

- Welcome to Eswatini | The Kingdom of Eswatini (Official Eswatini tourism website)

.svg.png)