Smart card

A smart card, chip card, or integrated circuit card (ICC) is a physical electronic authorization device, used to control access to a resource. It is typically a plastic credit card-sized card with an embedded integrated circuit (IC) chip.[1] Many smart cards include a pattern of metal contacts to electrically connect to the internal chip. Others are contactless, and some are both. Smart cards can provide personal identification, authentication, data storage, and application processing.[2] Applications include identification, financial, mobile phones (SIM), public transit, computer security, schools, and healthcare. Smart cards may provide strong security authentication for single sign-on (SSO) within organizations. Numerous nations have deployed smart cards throughout their populations.

The universal integrated circuit card, or SIM card, is also a type of smart card. As of 2015, 10.5 billion smart card IC chips are manufactured annually, including 5.44 billion SIM card IC chips.[3]

History

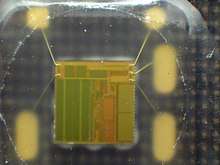

The basis for the smart card is the silicon integrated circuit (IC) chip.[4] It was invented by Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959, and was made possible by Mohamed M. Atalla's silicon surface passivation process (1957) and Jean Hoerni's planar process (1959).[5][6][7] The invention of the silicon integrated circuit led to the idea of incorporating it onto a plastic card in the late 1960s.[4] Smart cards have since used MOS integrated circuit chips, along with MOS memory technologies such as flash memory and EEPROM (electrically erasable programmable read-only memory).[8]

Invention

.jpg)

The idea of incorporating an integrated circuit chip onto a plastic card was first introduced by two German engineers in the late 1960s, Helmut Gröttrup and Jürgen Dethloff.[4] In February 1967, Gröttrup filed the patent DE1574074[9] in West Germany for a tamper-proof identification switch based on a semiconductor device. Its primary use was intended to provide individual copy-protected keys for releasing the tapping process at unmanned gas stations. In September 1968, Helmut Gröttrup, together with Dethloff as an investor, filed further patents for this identification switch, first in Austria[10] and in 1969 as subsequent applications in the United States[11][12], Great Britain, West Germany and other countries.[13]

Independently, Kunitaka Arimura of the Arimura Technology Institute in Japan developed a similar idea of incorporating an integrated circuit onto a plastic card, and filed a smart card patent in March 1970.[4][14] The following year, Paul Castrucci of IBM filed an American patent titled "Information Card" in May 1971.[14]

In 1974 Roland Moreno patented a secured memory card later dubbed the "smart card".[15][16] In 1976, Jürgen Dethloff introduced the known element (called "the secret") to identify gate user as of USP 4105156.[17]

In 1977, Michel Ugon from Honeywell Bull invented the first microprocessor smart card with two chips: one microprocessor and one memory, and in 1978, he patented the self-programmable one-chip microcomputer (SPOM) that defines the necessary architecture to program the chip. Three years later, Motorola used this patent in its "CP8". At that time, Bull had 1,200 patents related to smart cards. In 2001, Bull sold its CP8 division together with its patents to Schlumberger, who subsequently combined its own internal smart card department and CP8 to create Axalto. In 2006, Axalto and Gemplus, at the time the world's top two smart-card manufacturers, merged and became Gemalto. In 2008, Dexa Systems spun off from Schlumberger and acquired Enterprise Security Services business, which included the smart-card solutions division responsible for deploying the first large-scale smart-card management systems based on public key infrastructure (PKI).

The first mass use of the cards was as a telephone card for payment in French payphones, starting in 1983.

Carte bleue

After the Télécarte, microchips were integrated into all French Carte Bleue debit cards in 1992. Customers inserted the card into the merchant's point-of-sale (POS) terminal, then typed the personal identification number (PIN), before the transaction was accepted. Only very limited transactions (such as paying small highway tolls) are processed without a PIN.

Smart-card-based "electronic purse" systems store funds on the card, so that readers do not need network connectivity. They entered European service in the mid-1990s. They have been common in Germany (Geldkarte), Austria (Quick Wertkarte), Belgium (Proton), France (Moneo[18]), the Netherlands (Chipknip Chipper (decommissioned in 2001)), Switzerland ("Cash"), Norway ("Mondex"), Spain ("Monedero 4B"), Sweden ("Cash", decommissioned in 2004), Finland ("Avant"), UK ("Mondex"), Denmark ("Danmønt") and Portugal ("Porta-moedas Multibanco"). Private electronic purse systems have also been deployed such as the Marines corps (USMC) at Parris Island allowing small amount payments at the cafeteria.

Since the 1990s, smart cards have been the subscriber identity modules (SIMs) used in GSM mobile-phone equipment. Mobile phones are widely used across the world, so smart cards have become very common.

EMV

Europay MasterCard Visa (EMV)-compliant cards and equipment are widespread with the deployment led by European countries. The United States started later deploying the EMV technology in 2014, with the deployment still in progress in 2019. Typically, a country's national payment association, in coordination with MasterCard International, Visa International, American Express and Japan Credit Bureau (JCB), jointly plan and implement EMV systems.

Historically, in 1993 several international payment companies agreed to develop smart-card specifications for debit and credit cards. The original brands were MasterCard, Visa, and Europay. The first version of the EMV system was released in 1994. In 1998 the specifications became stable.

EMVCo maintains these specifications. EMVco's purpose is to assure the various financial institutions and retailers that the specifications retain backward compatibility with the 1998 version. EMVco upgraded the specifications in 2000 and 2004.[19]

EMV compliant cards were first accepted into Malaysia in 2005 [20] and later into United States in 2014. MasterCard was the first company that was allowed to use the technology in the United States. The United States has felt pushed to use the technology because of the increase in identity theft. The credit card information stolen from Target in late 2013 was one of the largest indicators that American credit card information is not safe. Target made the decision on April 30, 2014 that it would try to implement the smart chip technology in order to protect itself from future credit card identity theft.

Before 2014, the consensus in America was that there were enough security measures to avoid credit card theft and that the smart chip was not necessary. The cost of the smart chip technology was significant, which was why most of the corporations did not want to pay for it in the United States. The debate came when online credit theft was insecure enough for the United States to invest in the technology. The adaptation of EMV's increased significantly in 2015 when the liability shifts occurred in October by the credit card companies.

Development of contactless systems

Contactless smart cards do not require physical contact between a card and reader. They are becoming more popular for payment and ticketing. Typical uses include mass transit and motorway tolls. Visa and MasterCard implemented a version deployed in 2004–2006 in the U.S., with Visa's current offering called Visa Contactless. Most contactless fare collection systems are incompatible, though the MIFARE Standard card from NXP Semiconductors has a considerable market share in the US and Europe.

Use of "Contactless" smart cards in transport has also grown through the use of low cost chips NXP Mifare Ultralight and paper/card/PET rather than PVC. This has reduced media cost so it can be used for low cost tickets and short term transport passes (up to 1 year typically). The cost is typically 10% that of a PVC smart card with larger memory. They are distributed through vending machines, ticket offices and agents. Use of paper/PET is less harmful to the environment than traditional PVC cards . See also transport/transit/ID applications.

Smart cards are also being introduced for identification and entitlement by regional, national, and international organizations. These uses include citizen cards, drivers’ licenses, and patient cards. In Malaysia, the compulsory national ID MyKad enables eight applications and has 18 million users. Contactless smart cards are part of ICAO biometric passports to enhance security for international travel.

Design

A smart card may have the following generic characteristics:

- Dimensions similar to those of a credit card. ID-1 of the ISO/IEC 7810 standard defines cards as nominally 85.60 by 53.98 millimetres (3.37 in × 2.13 in). Another popular size is ID-000, which is nominally 25 by 15 millimetres (0.98 in × 0.59 in) (commonly used in SIM cards). Both are 0.76 millimetres (0.030 in) thick.

- Contains a tamper-resistant security system (for example a secure cryptoprocessor and a secure file system) and provides security services (e.g., protects in-memory information).

- Managed by an administration system, which securely interchanges information and configuration settings with the card, controlling card blacklisting and application-data updates.

- Communicates with external services through card-reading devices, such as ticket readers, ATMs, DIP reader, etc.

- Smart cards are typically made of plastic, generally polyvinyl chloride, but sometimes polyethylene-terephthalate-based polyesters, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene or polycarbonate.

Since April 2009, a Japanese company has manufactured reusable financial smart cards made from paper.[21]

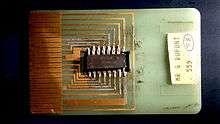

Contact smart cards

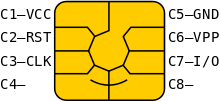

Contact smart cards have a contact area of approximately 1 square centimetre (0.16 sq in), comprising several gold-plated contact pads. These pads provide electrical connectivity when inserted into a reader,[24] which is used as a communications medium between the smart card and a host (e.g., a computer, a point of sale terminal) or a mobile telephone. Cards do not contain batteries; power is supplied by the card reader.

The ISO/IEC 7810 and ISO/IEC 7816 series of standards define:

- physical shape and characteristics,

- electrical connector positions and shapes,

- electrical characteristics,

- communications protocols, including commands sent to and responses from the card,

- basic functionality.

Because the chips in financial cards are the same as those used in subscriber identity modules (SIMs) in mobile phones, programmed differently and embedded in a different piece of PVC, chip manufacturers are building to the more demanding GSM/3G standards. So, for example, although the EMV standard allows a chip card to draw 50 mA from its terminal, cards are normally well below the telephone industry's 6 mA limit. This allows smaller and cheaper financial card terminals.

Communication protocols for contact smart cards include T=0 (character-level transmission protocol, defined in ISO/IEC 7816-3) and T=1 (block-level transmission protocol, defined in ISO/IEC 7816-3).

Contactless smart cards

Contactless smart cards communicate with technology (at data rates of 106–848 kbit/s). These cards require only proximity to an antenna to communicate. Like smart cards with contacts, contactless cards do not have an internal power source. Instead, they use an inductor to capture some of the incident radio-frequency interrogation signal, rectify it, and use it to power the card's electronics. Contactless smart media can be made with PVC, paper/card and PET finish to meet different performance, cost and durability requirements.

APDU transmission by a contactless interface is defined in ISO/IEC 14443-4.

Hybrids

Hybrid cards implement contactless and contact interfaces on a single card with dedicated modules/storage and processing.

- Dual-interface

Dual-interface cards implement contactless and contact interfaces on a single card with some shared storage and processing. An example is Porto's multi-application transport card, called Andante, which uses a chip with both contact and contactless (ISO/IEC 14443 Type B) interfaces.

USB

The CCID (Chip Card Interface Device) is a USB protocol that allows a smart card to be connected to a computer, using a standard USB interface. This allows the smart card to be used as a security token for authentication and data encryption such as Bitlocker. A typical CCID is a USB dongle and may contain a SIM.

Applications

Financial

Smart cards serve as credit or ATM cards, fuel cards, mobile phone SIMs, authorization cards for pay television, household utility pre-payment cards, high-security identification and access badges, and public transport and public phone payment cards.

Smart cards may also be used as electronic wallets. The smart card chip can be "loaded" with funds to pay parking meters, vending machines or merchants. Cryptographic protocols protect the exchange of money between the smart card and the machine. No connection to a bank is needed. The holder of the card may use it even if not the owner. Examples are Proton, Geldkarte, Chipknip and Moneo. The German Geldkarte is also used to validate customer age at vending machines for cigarettes.

These are the best known payment cards (classic plastic card):

- Visa: Visa Contactless, Quick VSDC, "qVSDC", Visa Wave, MSD, payWave

- Mastercard: PayPass Magstripe, PayPass MChip

- American Express: ExpressPay

- Discover: Zip

- Unionpay: QuickPass

Roll-outs started in 2005 in the U.S. Asia and Europe followed in 2006. Contactless (non-PIN) transactions cover a payment range of ~$5–50. There is an ISO/IEC 14443 PayPass implementation. Some, but not all, PayPass implementations conform to EMV.

Non-EMV cards work like magnetic stripe cards. This is common in the U.S. (PayPass Magstripe and Visa MSD). The cards do not hold or maintain the account balance. All payment passes without a PIN, usually in off-line mode. The security of such a transaction is no greater than with a magnetic stripe card transaction.

EMV cards can have either contact or contactless interfaces. They work as if they were a normal EMV card with a contact interface. Via the contactless interface they work somewhat differently, in that the card commands enabled improved features such as lower power and shorter transaction times.

SIM

The subscriber identity modules used in mobile-phone systems are reduced-size smart cards, using otherwise identical technologies.

Identification

Smart-cards can authenticate identity. Sometimes they employ a public key infrastructure (PKI). The card stores an encrypted digital certificate issued from the PKI provider along with other relevant information. Examples include the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) Common Access Card (CAC), and other cards used by other governments for their citizens. If they include biometric identification data, cards can provide superior two- or three-factor authentication.

Smart cards are not always privacy-enhancing, because the subject may carry incriminating information on the card. Contactless smart cards that can be read from within a wallet or even a garment simplify authentication; however, criminals may access data from these cards.

Cryptographic smart cards are often used for single sign-on. Most advanced smart cards include specialized cryptographic hardware that uses algorithms such as RSA and Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA). Today's cryptographic smart cards generate key pairs on board, to avoid the risk from having more than one copy of the key (since by design there usually isn't a way to extract private keys from a smart card). Such smart cards are mainly used for digital signatures and secure identification.

The most common way to access cryptographic smart card functions on a computer is to use a vendor-provided PKCS#11 library. On Microsoft Windows the Cryptographic Service Provider (CSP) API is also supported.

The most widely used cryptographic algorithms in smart cards (excluding the GSM so-called "crypto algorithm") are Triple DES and RSA. The key set is usually loaded (DES) or generated (RSA) on the card at the personalization stage.

Some of these smart cards are also made to support the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standard for Personal Identity Verification, FIPS 201.

Turkey implemented the first smart card driver's license system in 1987. Turkey had a high level of road accidents and decided to develop and use digital tachograph devices on heavy vehicles, instead of the existing mechanical ones, to reduce speed violations. Since 1987, the professional driver's licenses in Turkey have been issued as smart cards. A professional driver is required to insert his driver's license into a digital tachograph before starting to drive. The tachograph unit records speed violations for each driver and gives a printed report. The driving hours for each driver are also being monitored and reported. In 1990 the European Union conducted a feasibility study through BEVAC Consulting Engineers, titled "Feasibility study with respect to a European electronic drivers license (based on a smart-card) on behalf of Directorate General VII". In this study, chapter seven describes Turkey's experience.

Argentina's Mendoza province began using smart card driver's licenses in 1995. Mendoza also had a high level of road accidents, driving offenses, and a poor record of recovering fines. Smart licenses hold up-to-date records of driving offenses and unpaid fines. They also store personal information, license type and number, and a photograph. Emergency medical information such as blood type, allergies, and biometrics (fingerprints) can be stored on the chip if the card holder wishes. The Argentina government anticipates that this system will help to collect more than $10 million per year in fines.

In 1999 Gujarat was the first Indian state to introduce a smart card license system.[25] As of 2005, it has issued 5 million smart card driving licenses to its people.[26]

In 2002, the Estonian government started to issue smart cards named ID Kaart as primary identification for citizens to replace the usual passport in domestic and EU use. As of 2010 about 1 million smart cards have been issued (total population is about 1.3 million) and they are widely used in internet banking, buying public transport tickets, authorization on various websites etc.

By the start of 2009, the entire population of Belgium was issued eID cards that are used for identification. These cards contain two certificates: one for authentication and one for signature. This signature is legally enforceable. More and more services in Belgium use eID for authorization.[27]

Spain started issuing national ID cards (DNI) in the form of smart cards in 2006 and gradually replaced all the older ones with smart cards. The idea was that many or most bureaucratic acts could be done online but it was a failure because the Administration did not adapt and still mostly requires paper documents and personal presence.[28][29][30][31]

On August 14, 2012, the ID cards in Pakistan were replaced. The Smart Card is a third generation chip-based identity document that is produced according to international standards and requirements. The card has over 36 physical security features and has the latest encryption codes. This smart card replaced the NICOP (the ID card for overseas Pakistani).

Smart cards may identify emergency responders and their skills. Cards like these allow first responders to bypass organizational paperwork and focus more time on the emergency resolution. In 2004, The Smart Card Alliance expressed the needs: "to enhance security, increase government efficiency, reduce identity fraud, and protect personal privacy by establishing a mandatory, Government-wide standard for secure and reliable forms of identification".[32] emergency response personnel can carry these cards to be positively identified in emergency situations. WidePoint Corporation, a smart card provider to FEMA, produces cards that contain additional personal information, such as medical records and skill sets.

In 2007, the Open Mobile Alliance (OMA) proposed a new standard defining V1.0 of the Smart Card Web Server (SCWS), an HTTP server embedded in a SIM card intended for a smartphone user.[33] The non-profit trade association SIMalliance has been promoting the development and adoption of SCWS. SIMalliance states that SCWS offers end-users a familiar, OS-independent, browser-based interface to secure, personal SIM data. As of mid-2010, SIMalliance had not reported widespread industry acceptance of SCWS.[34] The OMA has been maintaining the standard, approving V1.1 of the standard in May 2009, and V1.2 is expected was approved in October 2012.[35]

Smart cards are also used to identify user accounts on arcade machines.[36]

Public transit

Smart cards, used as transit passes, and integrated ticketing are used by many public transit operators. Card users may also make small purchases using the cards. Some operators offer points for usage, exchanged at retailers or for other benefits.[37] Examples include Singapore's CEPAS, Ontario's Presto card, Hong Kong's Octopus card, London's Oyster card, Ireland's Leap card, Brussels' MoBIB, Québec's OPUS card, San Francisco's Clipper card, Auckland's AT Hop, Brisbane's go card, Perth's SmartRider, Sydney's Opal card and Victoria's myki. However, these present a privacy risk because they allow the mass transit operator (and the government) to track an individual's movement. In Finland, for example, the Data Protection Ombudsman prohibited the transport operator Helsinki Metropolitan Area Council (YTV) from collecting such information, despite YTV's argument that the card owner has the right to a list of trips paid with the card. Earlier, such information was used in the investigation of the Myyrmanni bombing.

The UK's Department for Transport mandated smart cards to administer travel entitlements for elderly and disabled residents. These schemes let residents use the cards for more than just bus passes. They can also be used for taxi and other concessionary transport. One example is the "Smartcare go" scheme provided by Ecebs.[38] The UK systems use the ITSO Ltd specification. Other schemes in the UK include period travel passes, carnets of tickets or day passes and stored value which can be used to pay for journeys. Other concessions for school pupils, students and job seekers are also supported. These are mostly based on the ITSO Ltd specification.

Many smart transport schemes include the use of low cost smart tickets for simple journeys, day passes and visitor passes. Examples include Glasgow SPT subway. These smart tickets are made of paper or PET which is thinner than a PVC smart card e.g. Confidex smart media.[39] The smart tickets can be supplied pre-printed and over-printed or printed on demand.

In Sweden, as of 2018-2019, smart cards have started to be phased out and replaced by smart phone apps. The phone apps have less cost, at least for the transit operators who don't need any electronic equipment (the riders provide that). The riders are able buy tickets anywhere and don't need to load money onto smart cards. The smart cards are still in use for foreseeable future (as of 2019).

Computer security

Smart cards can be used as a security token.

Mozilla's Firefox web browser can use smart cards to store certificates for use in secure web browsing.[40]

Some disk encryption systems, such as VeraCrypt and Microsoft's BitLocker, can use smart cards to securely hold encryption keys, and also to add another layer of encryption to critical parts of the secured disk.

GnuPG, the well known encryption suite, also supports storing keys in a smart card.[41]

Smart cards are also used for single sign-on to log on to computers.

Schools

Smart cards are being provided to students at some schools and colleges.[42][43][44] Uses include:

- Tracking student attendance

- As an electronic purse, to pay for items at canteens, vending machines, laundry facilities, etc.

- Tracking and monitoring food choices at the canteen, to help the student maintain a healthy diet

- Tracking loans from the school library

- Access control for admittance to restricted buildings, dormitories, and other facilities. This requirement may be enforced at all times (such as for a laboratory containing valuable equipment), or just during after-hours periods (such as for an academic building that is open during class times, but restricted to authorized personnel at night), depending on security needs.

- Access to transportation services

Healthcare

Smart health cards can improve the security and privacy of patient information, provide a secure carrier for portable medical records, reduce health care fraud, support new processes for portable medical records, provide secure access to emergency medical information, enable compliance with government initiatives (e.g., organ donation) and mandates, and provide the platform to implement other applications as needed by the health care organization.[45][46]

Other uses

Smart cards are widely used to encrypt digital television streams. VideoGuard is a specific example of how smart card security worked.

Multiple-use systems

The Malaysian government promotes MyKad as a single system for all smart-card applications. MyKad started as identity cards carried by all citizens and resident non-citizens. Available applications now include identity, travel documents, drivers license, health information, an electronic wallet, ATM bank-card, public toll-road and transit payments, and public key encryption infrastructure. The personal information inside the MYKAD card can be read using special APDU commands.[47]

Security

Smart cards have been advertised as suitable for personal identification tasks, because they are engineered to be tamper resistant. The chip usually implements some cryptographic algorithm. There are, however, several methods for recovering some of the algorithm's internal state.

Differential power analysis involves measuring the precise time and electric current required for certain encryption or decryption operations. This can deduce the on-chip private key used by public key algorithms such as RSA. Some implementations of symmetric ciphers can be vulnerable to timing or power attacks as well.

Smart cards can be physically disassembled by using acid, abrasives, solvents, or some other technique to obtain unrestricted access to the on-board microprocessor. Although such techniques may involve a risk of permanent damage to the chip, they permit much more detailed information (e.g., photomicrographs of encryption hardware) to be extracted.

Benefits

The benefits of smart cards are directly related to the volume of information and applications that are programmed for use on a card. A single contact/contactless smart card can be programmed with multiple banking credentials, medical entitlement, driver's license/public transport entitlement, loyalty programs and club memberships to name just a few. Multi-factor and proximity authentication can and has been embedded into smart cards to increase the security of all services on the card. For example, a smart card can be programmed to only allow a contactless transaction if it is also within range of another device like a uniquely paired mobile phone. This can significantly increase the security of the smart card.

Governments and regional authorities save money because of improved security, better data and reduced processing costs. These savings help reduce public budgets or enhance public services. There are many examples in the UK, many using a common open LASSeO specification.[48]

Individuals have better security and more convenience with using smart cards that perform multiple services. For example, they only need to replace one card if their wallet is lost or stolen. The data storage on a card can reduce duplication, and even provide emergency medical information.

Advantages

The first main advantage of smart cards is their flexibility. Smart cards have multiple functions which simultaneously can be an ID, a credit card, a stored-value cash card, and a repository of personal information such as telephone numbers or medical history. The card can be easily replaced if lost, and, the requirement for a PIN (or other form of security) provides additional security from unauthorised access to information by others. At the first attempt to use it illegally, the card would be deactivated by the card reader itself.

The second main advantage is security. Smart cards can be electronic key rings, giving the bearer ability to access information and physical places without need for online connections. They are encryption devices, so that the user can encrypt and decrypt information without relying on unknown, and therefore potentially untrustworthy, appliances such as ATMs. Smart cards are very flexible in providing authentication at different level of the bearer and the counterpart. Finally, with the information about the user that smart cards can provide to the other parties, they are useful devices for customizing products and services.

Other general benefits of smart cards are:

- Portability

- Increasing data storage capacity

- Reliability that is virtually unaffected by electrical and magnetic fields.

Smart cards and electronic commerce

Smart cards can be used in electronic commerce, over the Internet, though the business model used in current electronic commerce applications still cannot use the full potential of the electronic medium. An advantage of smart cards for electronic commerce is their use customize services. For example, in order for the service supplier to deliver the customized service, the user may need to provide each supplier with their profile, a boring and time-consuming activity. A smart card can contain a non-encrypted profile of the bearer, so that the user can get customized services even without previous contacts with the supplier.

Disadvantages

The plastic or paper card in which the chip is embedded is fairly flexible. The larger the chip, the higher the probability that normal use could damage it. Cards are often carried in wallets or pockets, a harsh environment for a chip and antenna in contactless cards. PVC cards can crack or break if bent/flexed excessively. However, for large banking systems, failure-management costs can be more than offset by fraud reduction.

The production, use and disposal of PVC plastic is known to be more harmful to the environment than other plastics.[49] Alternative materials including chlorine free plastics and paper are available for some smart applications.

If the account holder's computer hosts malware, the smart card security model may be broken. Malware can override the communication (both input via keyboard and output via application screen) between the user and the application. Man-in-the-browser malware (e.g., the Trojan Silentbanker) could modify a transaction, unnoticed by the user. Banks like Fortis and Belfius in Belgium and Rabobank ("random reader") in the Netherlands combine a smart card with an unconnected card reader to avoid this problem. The customer enters a challenge received from the bank's website, a PIN and the transaction amount into the reader. The reader returns an 8-digit signature. This signature is manually entered into the personal computer and verified by the bank, preventing point-of-sale-malware from changing the transaction amount.

Smart cards have also been the targets of security attacks. These attacks range from physical invasion of the card's electronics, to non-invasive attacks that exploit weaknesses in the card's software or hardware. The usual goal is to expose private encryption keys and then read and manipulate secure data such as funds. Once an attacker develops a non-invasive attack for a particular smart card model, he or she is typically able to perform the attack on other cards of that model in seconds, often using equipment that can be disguised as a normal smart card reader.[50] While manufacturers may develop new card models with additional information security, it may be costly or inconvenient for users to upgrade vulnerable systems. Tamper-evident and audit features in a smart card system help manage the risks of compromised cards.

Another problem is the lack of standards for functionality and security. To address this problem, the Berlin Group launched the ERIDANE Project to propose "a new functional and security framework for smart-card based Point of Interaction (POI) equipment".[51]

See also

- Java Card

- Keycard lock

- List of smart cards

- MULTOS

- Open Smart Card Development Platform

- Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard

- Proximity card

- Radio-frequency identification

- SNAPI

- Smart card management system

References

- "ISO/IEC 7816-2:2007 – Assignment of contacts C4 and C8". www.iso.org. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- Multi-application Smart Cards. Cambridge University Press.

- Tait, Don (August 25, 2016). "Smart card IC shipments to reach 12.8 billion units in 2020". IHS Technology. IHS Markit. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Chen, Zhiqun (2000). Java Card Technology for Smart Cards: Architecture and Programmer's Guide. Addison-Wesley Professional. pp. 3-4. ISBN 9780201703290.

- Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 120 & 321-323. ISBN 9783540342588.

- Bassett, Ross Knox (2007). To the Digital Age: Research Labs, Start-up Companies, and the Rise of MOS Technology. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780801886393.

- Sah, Chih-Tang (October 1988). "Evolution of the MOS transistor-from conception to VLSI" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 76 (10): 1280–1326 (1290). Bibcode:1988IEEEP..76.1280S. doi:10.1109/5.16328. ISSN 0018-9219.

Those of us active in silicon material and device research during 1956–1960 considered this successful effort by the Bell Labs group led by Atalla to stabilize the silicon surface the most important and significant technology advance, which blazed the trail that led to silicon integrated circuit technology developments in the second phase and volume production in the third phase.

- Veendrick, Harry J. M. (2017). Nanometer CMOS ICs: From Basics to ASICs. Springer. p. 315. ISBN 9783319475974.

- DE application 1574074, Gröttrup, Helmut, "Nachahmungssicherer Identifikationsschalter", published 1971-11-25

- AT patent 287366, Dethloff, Jürgen & Helmut Gröttrup, "Identifizierungsschalter", issued 1971-01-21, assigned to Intelectron Patentverwaltung

- US patent 3641316, Dethloff, Jürgen & Helmut Gröttrup, "Identifcation Switch", issued 1972-02-08

- US patent 3678250, Dethloff, Jürgen & Helmut Gröttrup, "Identification Switch", issued 1972-07-18

- Böttge, Horst; Mahl, Tobias; Kamp, Michael (2013). Giesecke+Devrient (ed.). From Eurocheque Card to Mobile Security 1968-2012. Battenberg Gietl Verlag. ISBN 978-3866465497.

- Jurgensen, Timothy M.; Guthery, Scott B. (2002). Smart Cards: The Developer's Toolkit. Prentice Hall Professional. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780130937308.

- "Monticello Memoirs Program". Computerworld honors. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- "history of smartcard invention". Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "Espacenet – Original document". Worldwide.espacenet.com. 1978-08-08. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- Moneo's website (in French).

- EMVco

- "US learns from Malaysia, 10 years later". The Rakyat Post.

- "development of the "KAMICARD" IC card made from recyclable and biodegradable paper". Toppan Printing Company. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- ISO/IEC 7816-2:1999/Amd 1:2004 Assignment of contacts C4 and C8.

- ISO/IEC 7816-2:2007. Identification cards – Integrated circuit cards – Part 2: Cards with contacts – Dimensions and location of the contacts.

- "About Smart Cards: Introduction: Primer". Secure Technology Alliance. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Smart Card License System

- "Smart Card Driving License System in Gujarat"

- "Taalkeuze/Choix de langue fedict.belgium.be". Eid.belgium.be. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- http://www.eldiario.es/turing/dni-electronico-dnie_0_179182675.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - http://www.ticbeat.com/tecnologias/reportaje-dni-electronico/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "FRACASO DEL DNI ELECTRONICO". A las pruebas me remito (in Spanish). 2015-05-04. Retrieved 2018-06-06.

FAILURE OF THE ELECTRONIC ID

- "El DNI electrónico ha muerto: ¡larga vida al DNI 3.0!" (in Spanish).

The electronic DNI has died: long live the DNI 3.0!

- "Emergency Response Official Credentials: An Approach to Attain Trust in Credentials across Multiple Jurisdictions for Disaster Response and Recovery". January 3, 2011.

- "OMA Newsletter 2007 Volume 2". Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- Martin, Christophe (30 June 2010). "Update from SIMalliance on SCWS". Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- "OMA Smart Card Web Server (SCWS)". Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- "What is "Aime"?". Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Octopus Card Benefits

- "Smartcare go". Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- "Smart Tickets". Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- Mozilla certificate store

- smartcard howto for GNUPG

- Varghese, Sam (2004-12-06). "Qld schools benefit from smart cards". The Age.

- CreditCards.com (2009-10-27). "Cashless lunches come to Australian schools". Australia.creditcards.com. Archived from the original on 2010-11-29. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- "News Release - Smart card technology to monitor smart food choices in schools". Ifr.ac.uk. 2005-07-14. Archived from the original on 2005-11-20. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- Smartcardalliance.org

- Fernández-Alemán, José Luis; Señor, Inmaculada Carrión; Lozoya, Pedro Ángel Oliver; Toval, Ambrosio (2013). "Security and privacy in electronic health records: A systematic literature review". Journal of Biomedical Informatics. Elsevier BV. 46 (3): 541–562. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2012.12.003. ISSN 1532-0464. PMID 23305810.

Recent years have witnessed the design of standards and the promulgation of directives concerning security and privacy in EHR systems. However, more work should be done to adopt these regulations and to deploy secure EHR systems.

- MYKAD SDK

- Lasseo#Examples of Smart Card Schemes using LASSeO

- "PVC free". Greepeace. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- Bar-El, Hagai. "Known Attacks Against Smartcards" (PDF). Discretix Technologies Ltd. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- "Related Initiatives". Home web for The Berlin Group. The Berlin Group. 2005-08-01. Archived from the original on 2006-05-07. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

Further reading

- Rankl, W.; W. Effing (1997). Smart Card Handbook. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-96720-3.

- Guthery, Scott B.; Timothy M. Jurgensen (1998). SmartCard Developer's Kit. Macmillan Technical Publishing. ISBN 1-57870-027-2.