Silwan

Silwan (Arabic: سلوان,[1] Hebrew: כְּפַר הַשִּׁילוֹחַ Kfar ha-Shiloaḥ) is a predominantly Palestinian neighborhood on the outskirts of the Old City of Jerusalem.[2] Forty Jewish families also live in the area.[3] Silwan is located in East Jerusalem.[4] Silwan began as a farming village, dating back to the 7th century according to local traditions, while the earliest mention of the village is from the year 985. From the 19th century onwards, the village was slowly being incorporated into Jerusalem until it became an urban neighborhood.

After the 1948 war, the village came under Jordanian rule. Jordanian rule lasted until the 1967 Six-Day War, since which it has been occupied by Israel. Silwan is administered as part of the Jerusalem Municipality.

In 1980, Israel incorporated East Jerusalem (of which Silwan is a part) into its claimed capital city Jerusalem through the Jerusalem Law, a basic law in Israel. The move is considered by the international community as illegal under international law,[5] but the Israeli government disputes this. According to Haaretz, the Israeli government has worked closely with the right-wing settler organization Ateret Cohanim to evict Palestinians living on property whether classified formerly as heqdesh (property pledged to a temple) or not, especially in the Batan el-Hawa area of Silwan.[6]

Depending on how the neighborhood is defined, the Palestinian residents in Silwan number 20,000 to 50,000 while there are about 500 to 2,800 Jews.[7][8]

Geography

History

Iron Age

In the ancient period, the area where the village stands was occupied by the necropolis of the Biblical kingdom.[9][10][11] In the valley below, according to the Hebrew Bible, "the waters of Shiloah go softly" (from the Gihon Spring; Isaiah 8:6) and "the Pool of Siloam" (Nehemiah 3:15) to water what since King Solomon became known as the king's garden (Jeremiah 39:4; 52:7; 2 Kings 25:4; Nehemiah 3:15).[12]

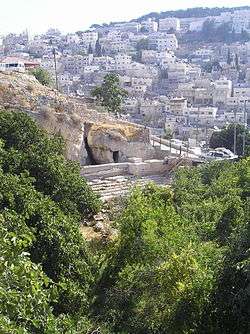

The necropolis, or ancient cemetery, is an archaeological site of major significance. It contains fifty rock-cut tombs of distinguished calibre, assumed to be the burial places of the highest-ranking officials of the Judean kingdom.[9] Tomb inscriptions are in Hebrew.[9] The "most famous" of the ancient rock-cut tombs in Silwan is finely carved, the one known as the Tomb of Pharaoh's daughter.[9] Another notable tomb, called the Tomb of the Royal Steward is now incorporated into a modern-period house.[9] The ancient inscription informs us that it is the final resting place of ""...yahu who is over the house."[9] The first part of the Hebrew name is effaced, but it refers to a Judean royal steward or chamberlain.[9] It is now in the collection of the British Museum.[9]

At their first thorough archaeological investigation, all of the tombs were long since emptied, and their contents removed.[9] A great deal of destruction was done to the tombs over the centuries by Roman-period quarrying and later by their conversion for use as housing, both by monks in the Byzantine period, when some were used as churches, and later by Muslim villagers "...when the Arab village was built; tombs were destroyed, incorporated in houses or turned into water cisterns and sewage dumps."[11]

Roman period

During the Second Temple period, the King's Garden was used as a staging area for Jewish pilgrims who, during the festivals of Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot, used the spring-fed Pool of Siloam to wash and ritually purify themselves before ascending the Great Staircase to the Temple Mount while singing hymns based on Psalms. On Sukkot water was brought from the Pool of Siloam to the Temple and poured upon the altar (Suk iv 9) and the priests also drank of this water (Ab. R. N. xxxv).

Medieval Arab period

Local folklore dates Silwan to the arrival of the second Rashidun caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab from Arabia. According to one resident's version of the story, the Greeks were so impressed that the Caliph entered on foot while his servant rode on a camel that they presented him with the key to the city. The Caliph thereafter granted the wadi to "Khan Silowna," an agricultural community of cave dwellers living ancient rock-cut tombs along the face of the eastern ridge.[13]

In medieval Muslim tradition, the spring of Silwan (Ayn Silwan) was among the four most sacred water sources in the world. The others were Zamzam in Mecca, Ayn Falus in Beisan and Ayn al-Baqar in Acre.[14] Silwan is mentioned as "Sulwan" by the 10th-century Arab writer and traveller al-Muqaddasi. In 985 he noted that the village in the outskirts of Jerusalem and south of the village was ′Ain Sulwan ("Spring of Siloam") which provided "fairly good water" that irrigated the large gardens that the third Rashidun caliph, 'Othman ibn 'Affan, endowed as a waqf to the impoverished residents of Jerusalem. Al-Muqaddasi further wrote "It is said that on the Night of 'Arafat the water of the holy well Zamzam, at Makkah, comes underground to the water of the Spring (of Siloam). The people hold a festival here on that evening."[15]

Ottoman period

In 1596, Ayn Silwan appeared in Ottoman tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Quds of the Liwa of Quds, with a population of 60 households, all Muslim. They paid a total of 35,500 akçe in taxes, and all of the revenues went to a Waqf.[16]

In 1834, during a large-scale peasants' rebellion against Ibrahim Pasha,[17] thousands of rebels infiltrated Jerusalem through ancient underground sewage channels leading to the farm fields of the village of Silwan.[18] A traveller to Palestine in 1883, T. Skinner, wrote that the olive groves near Silwan were a gathering place for Muslims on Fridays.[19]

In 1838 Silwan was noted as a Muslim village, part of el-Wadiyeh district, located east of Jerusalem.[20]

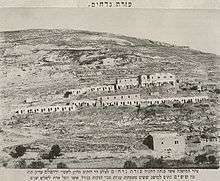

A photograph of the village taken between 1853 and 1857 by James Graham can be found on page 35 of Picturing Jerusalem by photographers James Graham and Mendel Diness, it shows the western part of the modern village as empty of habitations, a few trees are scattered across the southern ridge with the small village confined to the ridgetop east of the valley.[21]

In the mid-1850s, the villagers of Silwan were paid £100 annually by the Jews in an effort to prevent the desecration of graves on the Mount of Olives.[22] Jewish visitors to the Western Wall were also required to pay a tax to the inhabitants of Silwan, which by 1863 was 10,000 Piastres.[23] Nineteenth-century travellers described the village as a robbers' lair.[24] Charles Wilson wrote that "the houses and the streets of Siloam, if such they may be called, are filthy in the extreme.” Charles Warren depicted the population as a lawless set, credited with being "the most unscrupulous ruffians in Palestine.”[25]

An official Ottoman village list from about 1870 showed that Silwan had a total of 92 houses and a population of 240, though the population count included only men.[26][27]

In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described Silwan as a "village perched on a precipice and badly built of stone. The waters is brought from Ain Umm ed Deraj. There are numerous caves among and behind the houses, which are used as stables by the inhabitants."[28]

Modern settlement of the western ridge of the modern urban neighborhood of Silwan, called Wadi Hilweh in Arabic and dubbed in 1920 "the City of David" by Jewish-French archaeologist de:Raymond Weill (1874-1950),[29] began in 1873-1874, when the Meyuchas family moved out of the Old City to a new home on the ridge.[30]

In books published between 1888-1911, travellers describe the valley floor as verdant and cultivated,[31][32] with the stony village perched along the top of the eastern ridge hillside.[33] The village of Silwan was located on the eastern slope of the Kidron Valley, above the outlet of the Gihon Spring opposite Wadi Hilweh. The villagers cultivated the arable land in the Kidron Valley, which in biblical tradition formed the king's gardens during the Davidic dynasty,[12] to grow vegetables for market in Jerusalem.[34]

In 1881–82, a group of Jews arrived from Yemen as a result of messianic fervor.[35][36] The year had special meaning to them, for which some thirty Yemenite Jewish families set out from Sana'a for the Holy Land.[37] It was an arduous journey that took them over half a year to reach Jerusalem, where they arrived destitute of all things.[38] Upon reaching Jerusalem, they sought shelter in the caves and grottoes in the hills facing Jerusalem's walls and Wadi Hilweh (the City of David),[39] while others moved to Jaffa. Initially shunned by the Jews of the Old Yishuv, who did not recognize them as Jews due to their dark complexions, unfamiliar customs, and strange pronunciation of Hebrew, they had to be given shelter by the Christians of the Swedish-American colony, who called them Gadites.[35][36][40] Eventually, to end their reliance on Christian charity, Jewish philanthropists purchased land in the Silwan valley to establish a neighbourhood for them. By 1884, the Yemenites had settled into new stone houses at the south end of the Arab village, built for them by a Jewish charity called Ezrat Niddahim.[41] Up to 200 Yemenite Jews lived in the newly built neighbourhood, called Kfar Hashiloach (Hebrew: כפר השילוח, lit.: Siloam Village) or the "Yemenite Village."[42] The neighbourhood included a place of worship now known as the Old Yemenite Synagogue.[41][43] Construction costs were kept low by using the Shiloah spring as a water source instead of digging cisterns. An early 20th-century travel guide writes: In the "village of Silwan, east of Kidron ... some of the fellah dwellings [are] old sepulchers hewn in the rocks. During late years a great extension of the village southward has sprung up, owing to the settlement here of a colony of poor Jews from Yemen, etc. many of whom have built homes on the steep hillside just above and east of Bir Eyyub."[44]

In 1896 the population of Silwan was estimated to be about 939 persons.[45]

By 1910, the Yemenite Jewish community in Jerusalem and in Silwan purchased on credit a parcel of ground on the Mount of Olives for burying their dead, through the good agencies of Albert Antébi and with the assistance of the philanthropist, Baron Edmond Rothschild. The next year, the community was coerced into buying its adjacent property, by insistence of the Mukhtar (headman) of the village Silwan, and which considerably added to their holdings.[46]

British Mandate

At the time of the 1922 census of Palestine, "Selwan (Kfar Hashiloah)" had a population of 1,901 persons; 1,699 Muslims, 153 Jews and 49 Christians,[47] where the Christians were 16 Roman Catholics and 33 Syrian Catholics.[48] In the same year, Baron Edmond de Rothschild bought several acres of land there and transferred it to the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association.[49] By the time of the 1931 census, Silwan had 630 occupied houses and a population of 2968; 2,553 Muslims, 124 Jews and 91 Christians (the last including the Latin, Greek and St. Stephens convents).[50]

In the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine, the Yemenite community was removed from Silwan by the Welfare Bureau of the Va'ad Leumi into the Jewish Quarter as security conditions for Jews worsened,[51] and in 1938, the remaining Yemenite Jews in Silwan were evacuated by the Jewish Community Council on the advice of the police.[52][53] According to documents in the custodian office and real estate and project advancement expert Edmund Levy, the homes of the Yemenite Jews were occupied by Arab families without registering ownership.[54][55]

The British Mandatory government began annexing parts of Silwan to the Jerusalem Municipality, a process completed by the final Jordanian annexation of remaining Silwan in 1952.

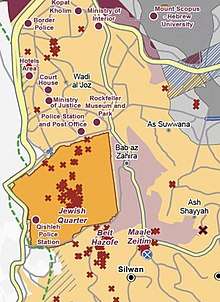

In the twentieth century, Silwan grew northward towards Jerusalem, expanding from a small farming village into an urban neighborhood. Modern Arab Silwan encompasses Old Silwan (generally to the south), the Yemenite village (to the north), and the once-vacant land between. Today Silwan follows the ridge of the southern peak of the Mount of Olives to the east of the Kidron Valley, from the ridge west of the Ophel up to the southern wall of the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif.

In the 1945 statistics the population of Silwan was 3,820; 3,680 Muslims and 140 Christians,[56] with a total of 5,421 dunams of land according to an official land and population survey.[57] Of this, Arabs used 58 dunams were for plantations and irrigable land and 2,498 for cereals, while Jews used 51 for cereals.[58] A total of 172 dunams were classified as built-up (urban) land.[59]

Jordanian era

After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Silwan came under Jordanian administration along with the rest of the West Bank, and land there owned by Jews was managed by the Jordanian Custodian of Enemy Property.[60] It remained under Jordanian rule until 1967, when Israel captured the Old City and surrounding region. Until then, the village had delegates in the Jerusalem City Council.

Post 1967

Since the 1967 Six-Day War Silwan has been under Israeli occupation, and Jewish organizations have sought to re-establish a Jewish presence there.

In 1987, the Permanent Representative of Jordan to the United Nations wrote to the Secretary-General to inform him of Israeli settlement activity; his letter noted that an Israeli company had taken over two Palestinian houses in the neighborhood of al-Bustan, also called King's Garden, after evicting their occupants, claiming the houses were its property.[61] City of David (Wadi Hilweh), an area of Silwan close to the southern wall of the Old City, and its neighborhood of al-Bustan, has been ever since a focus of Jewish settlement.

The Ir David Foundation and the Ateret Cohanim organizations are promoting resettlement of Jews in the neighborhood in cooperation with the Committee for the Renewal of the Yemenite Village in Shiloah.[62][63][64]

Wadi Hilweh/City of David in Silwan (West)

The City of David (Hebrew: Ir David), an archeological site believed to be the original site of Jerusalem, is located within Silwan.[62]

Silwan (East)

In 2003, Ateret Cohanim built a seven-storey apartment building known as Beit Yonatan (named for Jonathan Pollard) without a permit. In 2007, the courts ordered the eviction of the residents,[65] but the building was approved retroactively.[66] In 2008 a plan was submitted for a building complex including a synagogue, 10 apartments, a kindergarten, a library and underground parking for 100 cars in a location 200 meters from the Old City walls.[67]

In September 2014, the Ir David Foundation helped Jews move into 25 apartments in 7 different buildings in Silwan.[68] In response to this move, on 2 October 2014, the European Union condemned settlement expansion in Silwan.[69]

On 15 June 2016, Jerusalem's City Hall approved the construction of a three-storey residential house for Jews wishing to make Silwan their home.[70]

Palestinian cultural activities

The Silwan Ta’azef Music School opened in October 2007. Since November 2007, an art program, language courses for women, men and children, leadership training for teenage girls, cooking classes, an embroidery club and swimming classes have opened in Silwan. In 2009, a local library was established. The Silwan theater group is led by a professional actress from Bethlehem.[71] Many of these activities take place at the Madaa Silwan Creative Center.[72]

Demography

The Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem by the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies put the number of residents to 19,050 in 2012.[73] However, the Palestinian neighborhoods in Jerusalem are difficult to define, in contrast to the Jewish neighborhoods, because dense construction has blurred older boundaries and Silwan is now merged with Ras al-Amud, Jabel Mukaber and Abu Tor. The Palestinian residents in Silwan number 20,000 to 50,000 while there are fewer than 700 Jews.[74]

Jewish settlements

In 1991, a movement was formed to promote Jewish settlement in Silwan.[75][76] Some Silwan properties had already been declared absentee property in the 1980s, and suspicions arose that a number of claims filed by Jewish organizations had been accepted by the Custodian without any site visits or follow-up.[77] Property in Silwan has been purchased by Jews through indirect sales, some by invoking the Absentee Property Law.[78] In other cases, the Jewish National Fund signed protected tenant agreements that enabled construction to proceed without a tender process.[79]

In December 2011, a board member of the Jewish National Fund's US fundraising arm resigned in protest after a 20-year legal process came to a head with an order for the eviction of a Palestinian family from a JNF-owned home. The home had been acquired via the Absentee Property Law.[80][81][82] Several days before the order was carried out, JNF announced it would be delayed.[83]

As of 2004, more than 50 Jewish families live in the area,[84] some in homes acquired from Arabs who claim they did not know they were selling their homes to Jews,[85] some in Beit Yonatan.

Overnight on 30 September 2014 at 1:30 am, settlers, supported by police officers and reportedly connected to the Ir David Foundation, commonly known as Elad, entered 25 houses in 7 buildings which previously belonged to several Palestinian families in the neighborhood, in what was the largest Israeli purchase of homes in Silwan since 1986.[86] Most were vacant, but in one house where a family was evicted a confrontation broke out. Details concerning the process whereby the properties were purchased are lacking, but Palestinian middle men appear to be involved,[87] buying the six houses, and then selling them to a private American company, Kendall Finance. Elad stated that the houses had been bought properly and legally. Advertisements were posted on Facebook offering Jewish ex-army veterans $140 a day to sit in the properties until families move in.[88] As those who sell land to Israelis may be sentenced to death by the PA, the son of one Palestinian family who sold his property has fled Jerusalem, in fear for his life.[86][89] Some of the Palestinian families claiming ownership intended to get the settlers out by taking legal steps.[87]

White House spokesman Josh Earnest, in a condemnation of the takeover, described the new occupants as "individuals who are associated with an organization whose agenda, by definition, stokes tensions between Israelis and Palestinians." Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu was "baffled" by US criticism, deeming it "un-American" to criticize the legal purchase of homes in East Jerusalem to either Jews or Arabs.[88]

Rabbis for Human Rights-North America, which changed its name to T'ruah in 2012, accused Elad of creating a "method of expelling citizens from their properties, appropriating public areas, enclosing these lands with fences and guards, and banning the entrance of the local residents...under the protection of a private security force."[90] Approximately 1,500 supporters of RHR-NA/T'ruah wrote to Russell Robinson,[91] CEO of JNF-US, to demand an end to the eviction of a Silwan family.

A ruling handed down by the Jerusalem Magistrats Court in January 2020 gave a substantial boost to efforts by the settler organization Ateret Cohanim to evict large numbers of Palestinians in Silwan from their homes. The organization managed to take over control of an Ottoman era (19th century) Jewish trust, called the Benvenisti Trust after Rabbi Moshe Benvenisti, and claims that land in areas of Silwan, such as the Batan al-Hawa neighboruhood, was 'sacred religious land' and that Palestinians residing on this trust land were illegal squatters. The decisions are thought to effectively threaten with displacement some 700 Palestinians in Silwan.[92]

Housing demolition and construction permits

In 2005, the Israeli government planned to demolish 88 Arab homes in al-Bustan neighborhood built without permits[93] but they were not found illegal in a municipal court.[94]

According to the State Comptroller's report, there were 130 illegal structures in Silwan in 2009, a tenfold increase since 1967. When enforcement of the building code began in al-Bustan in 1995, thirty illegal structures were found, mostly old residential buildings.[95] By 2004, the number of illegal structures rose to 80. The municipality launched legal proceedings against 43 and demolished 10, but these were soon replaced by new buildings.[95]

The group Ir Amim argues that the illegal construction is due to insufficient granting of permits by the Jerusalem municipality. They say that under Israeli administration, fewer than 20 permits, mainly minor, were issued for this part of Silwan, and that as a result, most building in this part of Silwan and the whole neighborhood generally lack permits.[96] They also say that as of 2009, the vast majority of buildings in the neighborhood were built without permits, in particular in al-Bustan.[97] In 2010, Ir Amim's petition to halt a municipal zoning plan for the City of David area was rejected. The plan does not call for demolition of illegal construction, but rather regulates where construction may continue. The group said that the plan favored the interests of Elad and the neighborhood's Jewish residents, while Elad said that the plan allotted only 15 percent of construction to Jews versus 85 percent to Arab residents. The mukhtar of Silwan objected to Ir Amim's petition against the plan. “We have said that there are good aspects of the plan and there are bad aspects of the plan, we’re still working it all out. But to come and say that the whole plan is bad, and to ask that it be done away with, then what have you accomplished? Nothing.”[98]

Environmental projects

Silwan has expanded onto designated greenspace on the floor of the Kidron Valley. A redevelopment plan proposed by Jerusalem mayor Nir Barkat calls for the establishment of a park to be called the Garden of the King.[99] UN Special Rapporteur Richard Falk said of the plan that "international law does not allow Israel to bulldoze Palestinian homes to make space for the mayor’s project to build a garden, or anything else."[100]

Archaeology

The ridge to the west of Silwan, known as the City of David, is believed to be the original Bronze Age and Iron Age site of Jerusalem. Archaeological exploration began in the 19th century. Vacant during most of the Ottoman period, Jewish and Arab settlement began in the late 19th century.[101] Islamic-era skeletons discovered in the course of excavations have disappeared.[102] ElAd was accused of excavating on Palestinian property[103] and beginning its work on the City of David tunnels before receiving a permit from the Jerusalem Municipality.[104]

In 2007, archaeologists unearthed under a parking lot a 2,000-year-old mansion that may have belonged to Queen Helene of Adiabene. The building includes storerooms, living quarters and ritual baths.[105]

In April 2008, the Israeli High Court temporarily halted excavations.[106][107]

Tree wars: Olive groves

In her 2009 publication entitled Tree Flags, legal scholar and ethnographer, Irus Braverman, describes how Palestinians identify olive groves as an emblem or symbol of their longtime, steadfast agricultural connection (tsumud) to the land.[108]:1[109][110]

In May 2010, a group of Israeli settlers torched "an 11-Dunam olive orchard in al-Rababa valley, in Silwan, south of the Old City of Jerusalem" which included the destruction of three olive trees that were over 300 years old.[111] In a 2011 New York Times article, these attacks were called "price tag" attacks.[112] Similar destruction of olive trees occurred in Jabal Jales (an area near Hebron) and in Huwara.[113] The United Nations reported that by 2013, 11,000 olive trees owned by Palestinians in the occupied West Bank had been damaged or destroyed.[114][114][115] Washington Post, October 2014:

"More than 80,000 Palestinian farmers derive a substantial portion of their annual income from olives. Harvesting the fruit, pressing the oil, selling and sharing the produce is a ritual of life."

References

- Palmer, 1881, pp. 319, 329

- Meron Benvenisti, 'Shady Dealings in Silwan,' Archived 2010-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. Ir Amim for an Equitable and Stable Jerusalem, May, 2009 p.5.

- Shimi Friedman, 'Adversity in a Snowball Fight: Jewish Childhood in the Muslim village of Sillwan,' in Drew Chappell (ed.) Children under construction: critical essays on play as curriculum, Peter Lang Publishing 2010, pp.259-276, pp.260-261.

- Archaeology and the struggle for Jerusalem BBC News. 5 February 2010

- "The Geneva Convention". BBC News. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- Nir Hasson, 'How Israel Helps Settler Group Move Jews Into East Jerusalem’s Silwan,' Haaretz 6 January 2016.

- Balofsky, Ahuva (May 8, 2015). "Jews Reclaim Synagogue in Arab Neighborhood in Jerusalem". Breaking Israel News | Latest News. Biblical Perspective.

- Sales, Ben. "In tense eastern Jerusalem, Arabs and Jews hunker down". www.timesofisrael.com.

- "Silwan, Jerusalem: The Survey of the Iron Age Necropolis," David Ussishkin, Tel Aviv University webpage.

- Bible Encyclopedia entry: Siloam International Standard Bible Encyclopedia.

- The Necropolis from the Time of the Kingdom of Judah at Silwan, Jerusalem, David Ussishkin, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 33, No. 2 (May, 1970), pp. 33-46.

- William P. Brown, Seeing the Psalms: a theology of metaphor ,Westminster John Knox Press, 2002, p. 68: attributed to Solomon in Ecclesiastes 2:4-6, and Josephus. See also Yee-Von Koh, Royal autobiography in the book of Qoheleth, Walter de Gruyter, 2006 p. 33, pp. 94-96.

- Jeffrey Yas."(Re)designing the City of David: Landscape, Narrative and Archaeology in Silwan"; Jerusalem Quarterly, Winter 2000, Issue 7

- Sharon, 1997, p. 24

- Muk., 171. Quoted in le Strange, 1890, p. 221

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 114

- "Jerusalem | History, Map, Culture, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Jerusalem in the 19th Century: The Old City Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, Part II, Chapter One: Ottoman Rule, pp. 90, 109, Yad Ben Zvi Institute & St. Martin's Press, New York, 1984

- Jerusalem in the 19th Century: The Old City Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, Part II, Chapter Two: The Muslim Community, p. 133, Yad Ben Zvi Institute & St. Martin's Press, New York, 1984

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 122

- Picturing Jerusalem; James Graham and Mendel Diness, Photographers, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 2007.

- Menashe Har-El (April 2004). Golden Jerusalem. Gefen Publishing House Ltd. p. 244. ISBN 978-965-229-254-4. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. 2002. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8386-3942-9.

- This is Jerusalem, Menashe Har-El, Jerusalem 1977, p.135

- "The Tombs of Silwan". The BAS Library. August 24, 2015.

- Socin, 1879, p. 161

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 124 also noted 92 houses

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 30

- Wendy Pullan; Maximilian Sternberg; Lefkos Kyriacou; Craig Larkin; Michael Dumper (20 November 2013). "David's City in Palestinian Silwan". The Struggle for Jerusalem's Holy Places. Routledge. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-317-97556-4.

- Yemin Moshe: The Story of a Jerusalem Neighborhood, Eliezer David Jaffe, Praeger, 1988, p. 51

- Handbook to the Mediterranean: Its Cities, Coasts and Islands, Robert Lambert Playfair, John Murray, Albemarle Street, London, 1892, p. 70.

- Biblical Geography and History, Charles Foster Kent, 1911 , p. 219

- The Holy Land and the Bible: A Book of Scripture Illustrations, Cunningham Geikie , 1888, New York, James Pott & Co. Publishers p.558

- Cyclopaedia of Biblical , Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature, John McClintock, Harper and Brothers, 1889, p. 745

- Tudor Parfitt (1997). The road to redemption: the Jews of the Yemen, 1900-1950. Brill's series in Jewish Studies, vol 17. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 53.

- Nini, Yehuda. The Jews of the Yemen, 1800-1914. Taylor & Francis. pp. 205–207. ISBN 978-3-7186-5041-5.

- Based on a numerological interpretation of the biblical verse "I shall go up on the date palm [tree]" (Song of Songs 7:9), in which the numerical value of the Hebrew words "on the date palm" (Hebrew: בתמר) - 642 - corresponded to the Hebrew year 5642 anno mundi (1881/82), with the millennium being abbreviated, it was expounded to mean, "I shall go up (meaning, make the pilgrimage) in the year 642 of the sixth millennium. Cf. Yehudei Teiman Be-Tel Aviv (The Jews of Yemen in Tel-Aviv), Yaakov Ramon, Jerusalem 1935, p. 5 (Hebrew); The Jews of Yemen in Tel-Aviv, p. 5 in PDF

- Yehudei Teiman Be-Tel Aviv (The Jews of Yemen in Tel-Aviv), Yaakov Ramon, Jerusalem 1935, p. 5 (Hebrew); The Jews of Yemen in Tel-Aviv, p. 5 in PDF

- "Streetwise: Yemenite steps - Magazine - Jerusalem Post". www.jpost.com.

- Messianism, Holiness, Charisma, and Community: The American-Swedish Colony in Jerusalem, 1881–1933, Yaakov Ariel and Ruth Kark , Church History, Vol. 65, No. 4 (Dec., 1996), p. 645

- Man, Nadav (9 January 2010). "Behind the lens of Hannah and Efraim Degani – part 7". Ynetnews.

- Moon, Luke (15 July 2019). "New York Times Ignores Silwan's Jewish Origins". Providence. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Sylva M. Gelber, No Balm in Gilead: A Personal Retrospective of Mandate Days in Palestine, McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, 1989 p.88

- Cook's Handbook for Palestine and Syria, Thomas Cook Ltd., 1907, p. 105

- Schick, 1896, p. 121

- Zekhor Le'Avraham, Shelomo al-Naddaf (ed. Uzziel Alnadaf), Jerusalem 1992, pp. 56–57 (Hebrew)

- Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- Barron, 1923, Table XIV, p. 45

- Zionist Organization of America; Jewish Agency for Israel. Economic Dept (1997). Israel yearbook and almanac. IBRT Translation/Documentation Ltd. p. 102. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Mills, 1932, p. 43

- Sylva M. Gelber, No balm in Gilead: a personal retrospective of mandate days in Palestine, Carleton University/McGill University Press 1989 pp. 56,88.

- Shragai, Nadav (January 4, 2004). "11 Jewish families move into J'lem neighborhood of Silwan". Haaretz.

- Palestine Post, August 15, 1938, p. 2

- Documents show Arabs illegally obtained Jewish homes in Silwan, Bill Hutman, Jerusalem Post. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- WHO OWNS THE LAND?, Gail Lichtman, Jerusalem Post. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 58 Archived 2018-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 104 Archived 2012-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 154 Archived 2014-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Fischbach, Michael R. (2000). State, Society, and Land in Jordan. Brill Publishers. p. 193. ISBN 978-90-04-11912-3.

- "Letter dated 16 October 1987 from the Permanent Representative of Jordan to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General" UN General Assembly Security Council

- Bronner, Yigal (1 May 2008). "Archaeologists for hire". The Guardian.

- "11 Jewish families move into J'lem neighborhood of Silwan – Haaretz – Israel News".

- Freedman, Seth (February 26, 2008). "Digging into trouble" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Meron Rapoport "The battle over settling Silwan simmers" Archived 2008-10-12 at the Wayback Machine Haaretz, June 12, 2007

- "Jerusalem Approves ‘Beit Yehonatan’ in Shiloach" Arutz Sheva, October 15, 2007

- Akiva Eldar."Plan to put synagogue in heart of East Jerusalem likely to be approved" Archived 2008-05-17 at the Wayback Machine; Haaretz, May 20, 2008

- Hasson, Nir (September 30, 2014). "Settlers Move Into 25 East Jerusalem Homes, Marking Biggest Influx in Decades" – via Haaretz.

- Statement by the Spokesperson on the Israeli decision for settlement expansion Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- "Jerusalem OKs new building for Jews in Arab neighborhood, drawing protest from Palestinians". Los Angeles Times (AP). June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- The Silwan Ta'azef Music School in Silwan

- "Prelude: Creating playgrounds in the Middle East". Archived from the original on March 7, 2011.

- "Table III/14 - Population of Jerusalem, by Age, Quarter, Sub-Quarter and Statistical Area, 2012" (PDF). Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. 2014.

- "East Jerusalem remains 'Arab' despite Jewish settlers, experts say". Haaretz. 2 October 2014.

- John Quigley, Flight Into the Maelstrom: Soviet Immigration to Israel and Middle East Peace, Ithaca Press, 1997 p.68.

- Hillel Cohen, The Rise and Fall of Arab Jerusalem: Palestinian Politics and the City since 1967, Routledge 2013 p.94.'Late in the Intifada, when Jewish settlement began in the Wadi Hilwe section of Silwan (“The City of David”) left-wing activists from Jerusalem worked together with people from Orient House in an attempt to stop the Jewish settlement in the neighbourhood '.

- Meron Rapoport.Land lords Archived 2008-12-20 at the Wayback Machine; Haaretz, January 20, 2005

- Joel Greenburg."Settlers Move Into 4 Homes in East Jerusalem"; New York Times, June 9, 1998

- Meron Rapoport."The republic of Elad"; Haaretz, April 23, 2006 [retrieved 27-05-2010]

- Haaretz and Nir Hasson (2011-12-14). "JNF board member resigns to protest eviction of East Jerusalem Palestinian family". Haaretz. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- Nir Hasson (2011-11-11). "Palestinian family given two weeks to vacate East Jerusalem home". Haaretz. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- Seth Morrison (2011-12-13). "JNF Board Member Quits Over Evictions". The Forward. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- Nir Hasson (2011-11-27). "JNF delays eviction of Palestinian family from East Jerusalem home". Haaretz. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- "Settlement Timeline". Foundation for Middle East Peace. July–August 2004. Archived from the original on 2006-07-19. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- Rapoport, Meron (2006-06-09). "The Maraga tapes". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2006-06-16. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- Reuters, 'Jewish settlers move into Palestinian homes in Old City's shadow', Ynetnews 30 September 2014.

- Nir Hasson, 'Ex-Islamic Movement man helped settlers' move on E. Jerusalem, say Palestinians,'Haaretz 3 October 2014.

- Daniel Estrin,'Sudden apartment takeovers in east Jerusalem spark anger,' The Times of Israel 3 October 2014.

- 'Rightist group chalking up biggest settler influx in East Jerusalem in decades,' Haaretz

- "RHR statement". Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- "Op-Ed: JNF should plant trees, not uproot families". March 2, 2012.

- 'Settlement Report [The Trump Plan Edition,']Foundation for Middle East Peace 31January 2020.

- "Jerusalem demolitions may spark repeat of 1996 riots". Ha'aretz. 2009-03-10. Archived from the original on 2009-03-13. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- "Jerusalem Municipality plans to demolish 88 homes in Silwan"; Al Ayyam Newspaper, June 1, 2005

- "Israel News | The Jerusalem post". www.jpost.com.

- "City of David- Silwan". Ir Amim. Archived from the original on 2011-08-23. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- "Shady Dealings in Silwan" (PDF). Ir Amim. May 2009.

- Abe, Selig (2010-05-03). "Court rejects NGO petition to halt Silwan planning scheme". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- Gan Hamelech residents wary of Barkat’s redevelopment plan, Abe Selig, Feb. 16, 2010, Jerusalem Post.

- Demolitions, new settlements in East Jerusalem could amount to war crimes – UN expert 29 June 2010. UN News Centre

- A photograph of the vacant ridge taken between 1853 and 1857 by James Grahm can be found on page 31 of Picturing Jerusalem; James Graham and Mendel Diness, Photographers, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 2007.

- Meron Rapaport."Islamic-era skeletons 'disappeared' from Elad-sponsored dig" Haaretz, June 1, 2008

- "Haaretz on Rabbis for Human Rights arrest".

- Meron Rapoport."City of David tunnel excavation proceeds without proper permit" Archived 2008-04-19 at the Wayback Machine; Haaretz, February 5th, 2007

- "Israeli archaeologists find 2,000-year-old mansion linked to historic queen". Ynetnews. June 12, 2007.

- "Israeli Supreme Court Intervenes in Silwan". Rabbis for Human Rights. 2008-03-23. Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- "Israeli High Court orders an end to excavations in Silwan"; IMEMC, March 18, 2008

- Planted Flags: Trees, Land, and Law in Israel/Palestine (PDF). Yale Agrarian Studies Colloquium. Buffalo, New York. 28 September 2010. p. 54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Staton, Bethan (21 January 2015). "The deep roots of the Palestine-Israel conflict: Palestinians have tended olive groves for decades, but Israelis are staking a claim by planting their own trees". Israel/Palestine. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Braverman, Irus (2009). Planted Flags: Trees, Land, and Law in Israel/Palestine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052176002X.

- Bannoura, Saed (13 May 2010), "Settler Torch Olive Orchard In Silwan", International Middle East Media Center

- Kershner, Isabel (3 October 2011). "Mosque Set on Fire in Northern Israel". New York Times. Jerusalem. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Kinder, Tabatha (24 October 2014). "Palestine: Jewish Settlers Torch 100 of World's Oldest Olive Trees". International Business News. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Booth, William (22 October 2014). "In West Bank, Palestinians gird for settler attacks on olive trees". Kfar Yassug, West Bank. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- "Nearly 11,000 Palestinian-owned trees damaged by Israeli settlers in 2013", United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine (UNISPAL), archived from the original on 22 January 2015, retrieved 23 January 2015

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Sharon, M. (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, A. 1. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10833-5.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Strange, le, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

External links

- Ancient Silwan (Shiloah) Siloam in Israel and The City of David

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Silwan & Ath Thuri (Fact Sheet) Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem, ARIJ

- Aerial photo, ARIJ

- Silwan (Shiloah) in Antiquity Archaeological Survey of Israel

- East Jerusalem: 'Every action in this area is very sensitive' - video, The Guardian

- East Jerusalem: Witnessing the truth - video, The Guardian

- Home Demolition and Forced Displacement in Silwan, The Civic Coalition for Palestinian Rights in Jerusalem

- A City Divided: Jerusalem's Most Contested Neighborhood, Vice News

- Overview of the Yemenite Village Adjacent to the Gihon Spring, by Ateret Cohanim