Shilling (British coin)

The shilling (1/-) was a coin worth one twentieth of a pound sterling, or twelve pence. It was first minted in the reign of Henry VII as the testoon, and became known as the shilling from the Old English scilling,[1] sometime in the mid-16th century, circulating until 1990. The word bob was sometimes used for a monetary value of several shillings, e.g. "ten-bob note". Following decimalisation on 15 February 1971 the coin had a value of five new pence. It was made from silver from its introduction in or around 1503 until 1947, and thereafter in cupronickel.

United Kingdom | |

| Value | 12 pence sterling |

|---|---|

| Mass | (1816–1970) 5.66 g |

| Diameter | (1816–1970) 23.60 mm |

| Edge | Milled |

| Composition | (1503–1816) Silver (1816–1920) 92.5% Ag (1920–1946) 50% Ag (1947–1970) Cupronickel[nb 1] |

| Years of minting | c. 1548-1966 |

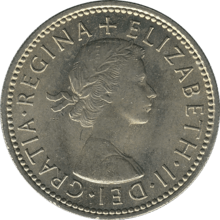

| Obverse | |

| |

| Design | Profile of the monarch (Elizabeth II design shown) |

| Designer | Mary Gillick |

| Design date | 1953 |

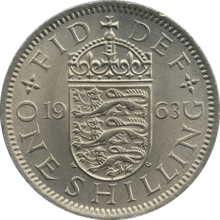

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Various (coat of arms of England design shown) |

| Designer | William Gardner |

| Design date | 1947 |

Prior to Decimal Day in 1971 there were 240 pence in one pound sterling. Twelve pence made a shilling, and twenty shillings made a pound. Values less than a pound were usually written in terms of shillings and pence, e.g. forty-two pence would be three shillings and six pence (3/6), pronounced "three and six". Values of less than a shilling were simply written in terms of pence, e.g. eight pence would be 8d.

Although the coin was not minted until the sixteenth century, the value of a shilling had been used for accounting purposes since the Anglo-Saxon period. The value of one shilling equalling 12d was set by the Normans following the conquest; prior to this various Anglo-Saxon coins equalling 4, 5, and 12 pence had all been known as shillings.[2]

History

The first coins of the pound sterling with the value of 12d were minted in 1503[3] or 1504[2] and were known as testoons. The testoon was one of the first English coins to bear a real (rather than a representative) portrait of the monarch on its obverse, and it is for this reason that it obtained its name from an Italian coin known as the testone, or headpiece, which had been introduced in Milan in 1474.[4] Between 1544 and 1551 the coinage was debased repeatedly by the governments of Henry VIII and Edward VI in an attempt to generate more money to fund foreign wars. This debasement meant that coins produced in 1551 had one-fifth of the silver content of those minted in 1544, and consequently the value of new testoons fell from 12d to 6d.[5] The reason the testoon decreased in value is that unlike today, the value of coins was determined by the market price of the metal contained within them. This debasement was recognised as a mistake, and during Elizabeth's reign newly minted coins, including the testoon (now known as the shilling), had a much higher silver content and regained their pre-debasement value.[6]

Shillings were minted during the reign of every English monarch following Edward VI, as well as during the Commonwealth, with a vast number of variations and alterations appearing over the years. The Royal Mint undertook a massive recoinage programme in 1816, with large quantities of gold and silver coin being minted. Previous issues of silver coinage had been irregular, and the last issue, minted in 1787, was not intended for issue to the public, but as Christmas gifts to the Bank of England's customers.[7] New silver coinage was to be of .925 (sterling) standard, with silver coins to be minted at 66 shillings to the troy pound.[8] Hence, newly minted shillings weighed 2⁄11 troy ounce, equivalent to 87.273 grains or 5.655 grams.

The Royal Mint debased the silver coinage in 1920 from 92.5% silver to 50% silver. Shillings of both alloys were minted that year.[9] This debasement was done because of the rising price of silver around the world, and followed the global trend of the elimination, or the reducing in purity, of the silver in coinage.[10] The minting of silver coinage of the pound sterling ceased completely in 1946 for similar reasons, exacerbated by the costs of the Second World War. New "silver" coinage was instead minted in cupronickel, an alloy of copper and nickel containing no silver at all.[11]

Beginning with Lord Wrottesley's proposals in the 1820s there were various attempts to decimalise the pound sterling over the next century and a half.[12][13] These attempts came to nothing significant until the 1960s when the need for a currency more suited to simple monetary calculations became pressing. The decision to decimalise was announced in 1966, with the pound to be redivided into 100, rather than 240, pence.[14] Decimal Day was set for 15 February 1971, and a whole range of new coins were introduced. Shillings continued to be legal tender with a value of 5 new pence until 31 December 1990.[15]

Design

Testoons issued during the reign of Henry VII feature a right-facing portrait of the king on the obverse. Surrounding the portrait is the inscription HENRICUS DI GRA REX ANGL Z FRA, or similar, meaning "Henry, by the Grace of God, King of England and France".[4] All shillings minted under subsequent kings and queens bear a similar inscription on the obverse identifying the monarch (or Lord Protector during the Commonwealth), with the portrait usually flipping left-facing to right-facing or vice versa between monarchs. The reverse features the escutcheon of the Royal Arms of England, surrounded by the inscription POSVI DEVM ADIVTORE MEVM, or a variant, meaning "I have made God my helper".[16]

Henry VIII testoons have a different reverse design, featuring a crowned Tudor rose, but those of Edward VI return to the Royal Arms design used previously.[17] Starting with Edward VI the coins feature the denomination XII printed next to the portrait of the king. Elizabeth I and Mary I shillings are exceptions to this; the former has the denomination printed on the reverse, above the coat of arms, and the latter has no denomination printed at all. Some shillings issued during Mary's reign bear the date of minting, printed above the dual portraits of Mary and Philip.[17]

Early shillings of James I feature the alternative reverse inscription EXURGAT DEUS DISSIPENTUR INIMICI, meaning "Let God arise and His enemies be scattered", becoming QVAE DEVS CONIVNXIT NEMO SEPARET, meaning "What God hath put together let no man put asunder" after 1604.[18][19]

In popular culture

A slang name for a shilling was a "bob" (plural as singular, as in "that cost me two bob"). The first recorded use was in a case of coining heard at the Old Bailey in 1789, when it was described as cant, "well understood among a certain set of people", but heard only among criminals and their associates.[20]

In much of West Africa, white people are called toubabs, which may derive from the colonial practice of paying locals two shillings for running errands.[21] An alternate etymology holds that the name is derived from French toubib, i.e. doctor.[22]

To "take the King's shilling" was to enlist in the army or navy, a phrase dating back to the early 19th century.[23]

To "cut someone off with a shilling", often quoted as "cut off without a shilling" means to disinherit. Although having no basis in British law, some believe that leaving a family member a single shilling in one's will ensured that it could not be challenged in court as an oversight.[24]

A popular legend holds that a shilling was the value of a cow in Kent, or a sheep elsewhere.[25]

References

- "Pounds, shillings & pence". Royal Mint Museum. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Requiem for the Shilling". Royal Mint Museum. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Abraham Rees (1819). The Cyclopaedia; Or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and Literature. – London, Longman, Hurst (usw.) 1819–20. Longman, Hurst. p. 403.

- "Shilling". Royal Mint Museum. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- John A. Wagner; Susan Walters Schmid (December 2011). Encyclopedia of Tudor England. ABC-CLIO. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-59884-298-2.

- Margherita Pascucci (22 May 2013). Philosophical Readings of Shakespeare: "Thou Art the Thing Itself". Palgrave Macmillan. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-137-32458-0.

- Manville, H. E.; Gaspar, P. P. (2004). "The 1787 Shilling – A Transition in Minting Technique" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 74: 84–103.

- Clancy, Kevin (1990). The recoinage and exchange of 1816–1817 (Ph.D.). University of Leeds.

- David Groom (10 July 2010). The Identification of British 20th Century Silver Coin Varieties. Lulu.com. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4457-5301-0.

- The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association. 1972.

- Christopher Edgar Challis (1992). A New History of the Royal Mint. Cambridge University Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-521-24026-0.

- The Bankers' Magazine. Waterlow. 1855. p. 139.

- Zupko, Ronald Edward (1990). Revolution in Measurement – Western European Weights and Measures Since the Age of Science. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society. 186. pp. 242–245. ISBN 0-87169-186-8.

- "The Story of Decimalisation". Royal Mint. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Stephen Eckett; Craig Pearce (2008). Harriman's Money Miscellany: A Collection of Financial Facts and Corporate Curiosities. Harriman House Limited. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-905641-95-6.

- Henry Noel Humphreys (1853). The Coin Collector's Manual, Or Guide to the Numismatic Student in the Formation of a Cabinet of Coins: Comprising an Historical and Critical Account of the Origin and Progress of Coinage, from the Earliest Period to the Fall of the Roman Empire. Bohn. p. 682.

- "Shilling". Coins of the UK. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Moriesson, Lieut.-Colonel H. W. (1907). "The Silver Coins of James I" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 4: 165–180.

- "Hammered coin inscriptions and their meanings". Paul Shields. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- Sessions Papers of the Old Bailey for 3 June 1789, quoted in "bob, n.8". Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 1989.

- The Gambia, eBizguides

- The Rough Guide to the Gambia, p. 65, Emma Gregg and Richard Trillo, Rough Guides, 2003

- "The King's Shilling". BBC History – Fact files. BBC. 2005-01-28. Archived from the original on 2014-05-13. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, E. Cobham Brewer, 1898

- Gerald Kennedy (1959). A Second Reader's Notebook. New York: Harper & Brothers.

External links

- Online Coin Club / Coin Type: Shilling – Listing of all issued shillings, with mintages, descriptions and photos