Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[3] is the virus strain that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a respiratory illness. It is colloquially known as the coronavirus, and was previously referred to by its provisional name 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV).[4][5][6][7] SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus.[8] It is contagious in humans, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has designated the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[9][10][11]

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 | |

|---|---|

| |

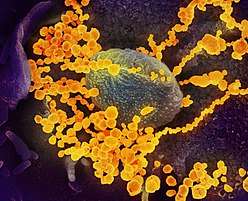

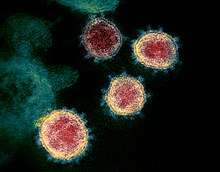

| Transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virions with visible coronae | |

| |

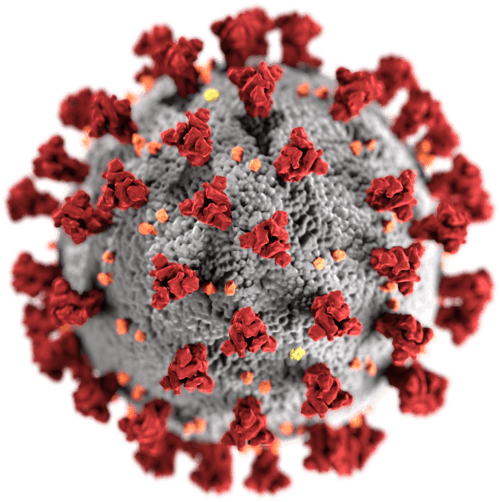

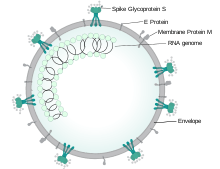

| Illustration of a SARS-CoV-2 virion[1] | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Phylum: | incertae sedis |

| Order: | Nidovirales |

| Family: | Coronaviridae |

| Genus: | Betacoronavirus |

| Subgenus: | Sarbecovirus |

| Species: | Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus |

| Strain: | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomically, SARS-CoV-2 is a strain of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV). It is believed to have zoonotic origins and has close genetic similarity to bat coronaviruses, suggesting it emerged from a bat-borne virus.[12][13][14][15] There is no evidence yet to link an intermediate animal reservoir, such as a pangolin, to its introduction to humans.[16][17] The virus shows little genetic diversity, indicating that the spillover event introducing SARS-CoV-2 to humans is likely to have occurred in late 2019.[18]

Epidemiological studies estimate each infection results in 1.4 to 3.9 new ones when no members of the community are immune and no preventive measures taken. The virus is primarily spread between people through close contact and via respiratory droplets produced from coughs or sneezes.[19][20] It mainly enters human cells by binding to the receptor angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).[12][21][22]

Terminology

Because the strain was discovered in Wuhan, China, it was initially sometimes referred to as the Wuhan coronavirus[23][24][25] or Wuhan virus.[26][27] The virus was originally formally referred to as the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)[5]. On Feburary 11th, 2020 this was changed to the official current name, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The Government of the United States and President Donald Trump have referred to the virus as the "Chinese virus" or "China virus."[28][29] Several sources consider these terms racially charged and believe they contribute to the xenophobia and racism caused by the outbreak.[28][29][30][31][32] The WHO discourages the use of names based upon locations such as MERS,[33][16][34] and sometimes refers to SARS-CoV-2 as "the COVID-19 virus" in public health communications to avoid confusion with the disease SARS.[35][36]

Virology

Infection

Human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was confirmed on 20 January 2020, during the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic.[11][37][38][39] Transmission occurs primarily via respiratory droplets from coughs and sneezes within a range of about 1.8 metres (6 ft).[20][40] Indirect contact via contaminated surfaces is another possible cause of infection.[41] Preliminary research indicates that the virus may remain viable on plastic and steel for up to three days, but does not survive on cardboard for more than one day or on copper for more than four hours;[42] the virus is inactivated by soap, which destabilises its lipid bilayer.[43][44] Viral RNA has also been found in stool samples from infected individuals.[45]

The degree to which the virus is infectious during the incubation period is uncertain, but research has indicated that the pharynx reaches peak viral load approximately four days after infection[46][47] or the first week of symptoms, and declines after.[48] On 1 February 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that "transmission from asymptomatic cases is likely not a major driver of transmission".[49] However, an epidemiological model of the beginning of the outbreak in China suggested that "pre-symptomatic shedding may be typical among documented infections" and that subclinical infections may have been the source of a majority of infections.[50] Similarly, a study of ninety-four patients hospitalized in January and February 2020 estimated patients shed the greatest amount of virus two to three days before symptoms appear and that "a substantial proportion of transmission probably occurred before first symptoms in the index case".[51]

There is some evidence of human-to-animal transmission of SARS-CoV-2, including examples in felids.[52][53] Some institutions have advised those infected with SARS-CoV-2 to restrict contact with animals.[54][55]

Reservoir

The first known infections from the SARS-CoV-2 strain were discovered in Wuhan, China.[12] The original source of viral transmission to humans remains unclear, as does whether the strain became pathogenic before or after the spillover event.[18][56][15] Because many of the first individuals found to be infected by the virus were workers at the Huanan Seafood Market,[57][58] it has been suggested that the strain might have originated from the market.[15][59] However, other research indicates that visitors may have introduced the virus to the market, which then facilitated rapid expansion of the infections.[18][60] A phylogenetic network analysis of 160 early coronavirus genomes sampled from December 2019 to February 2020 revealed that the virus type most closely related to the bat coronavirus was most abundant in Guangdong, China, and designated type "A". The predominant type among samples from Wuhan, "B", is more distantly related to the bat coronavirus than the ancestral type "A".[61][62]

Research into the natural reservoir of the virus strain that caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak has resulted in the discovery of many SARS-like bat coronaviruses, most originating in the Rhinolophus genus of horseshoe bats. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that samples taken from Rhinolophus sinicus show a resemblance of 80% to SARS-CoV-2.[14][63][64] Phylogenetic analysis also indicates that a virus from Rhinolophus affinis, collected in Yunnan province and designated RaTG13, has a 96% resemblance to SARS-CoV-2.[12][65] The pangolin coronavirus has up to 92% resemblance to SARS-CoV-2.[66]

Bats were initially considered to be the most likely natural reservoir of SARS-CoV-2,[67][68] but differences between the bat coronavirus sampled at the time and SARS-CoV-2 suggested that humans were infected via an intermediate host. Arinjay Banerjee at McMaster University notes that "the SARS virus shared 99.8% of its genome with a civet coronavirus, which is why civets were considered the source."[59] Although studies had suggested some likely candidates, the number and identities of intermediate hosts remains uncertain.[69] Nearly half of the strain's genome had a phylogenetic lineage distinct from known relatives.[70]

A metagenomic study published in 2019 previously revealed that SARS-CoV, the strain of the virus that causes SARS, was the most widely distributed coronavirus among a sample of Sunda pangolins.[71] On 7 February 2020, South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou announced that researchers had discovered a pangolin sample with a single viral nucleic acid sequence "99% similar" to that of a protein-coding RNA of SARS-CoV-2.[72] The authors state that "the receptor-binding domain of the S protein of the newly discovered Pangolin-CoV is virtually identical to that of 2019-nCoV, with one amino acid difference." The S protein, or spike protein, of the virus binds to the cell surface receptor during infection.[73] Pangolins are protected under Chinese law, but their poaching and trading for use in traditional Chinese medicine remains common.[74][75]

Recent phylogenetic analysis indicates that pangolins are a reservoir host of SARS-CoV-2-like coronaviruses. However, there is no evidence to link pangolins as an intermediate host of SARS-CoV-2 at this moment. While there is scientific consensus that bats are the ultimate source of coronaviruses, it is hypothesized that a SARS-CoV-2-like coronavirus originated in pangolins, jumped back to bats, and then jumped to humans, resulting in SARS-CoV-2. Based on whole genome sequence similarity, a highly similar pangolin coronavirus candidate strain was found to be less similar than RaTG13 to SARS-CoV-2 but are more similar than other bat coronaviruses to SARS-CoV-2.[66] Therefore, based on maximum parsimony, a specific population of bats is more likely to have directly transmitted SARS-CoV-2 to humans than a pangolin, while an evolutionary ancestor to bats was the source of general coronaviruses.[76] Microbiologists and geneticists in Texas have independently found evidence of reassortment in coronaviruses suggesting involvement of pangolins in the origin of SARS-CoV-2.[77]

Phylogenetics and taxonomy

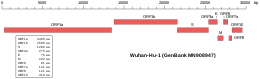

Genomic organisation of isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, the earliest sequenced sample of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| NCBI genome ID | MN908947 |

|---|---|

| Genome size | 29,903 bases |

| Year of completion | 2020 |

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the broad family of viruses known as coronaviruses.[24] It is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) virus, with a single linear RNA segment. Other coronaviruses are capable of causing illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS, fatality rate ~34%). It is the seventh known coronavirus to infect people, after 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, and the original SARS-CoV.[78]

Like the SARS-related coronavirus strain implicated in the 2003 SARS outbreak, SARS-CoV-2 is a member of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (beta-CoV lineage B).[79][80] Its RNA sequence is approximately 30,000 bases in length.[8] SARS-CoV-2 is unique among known betacoronaviruses in its incorporation of a polybasic cleavage site, a characteristic known to increase pathogenicity and transmissibility in other viruses.[15][81][82]

With a sufficient number of sequenced genomes, it is possible to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree of the mutation history of a family of viruses. By 12 January 2020, five genomes of SARS-CoV-2 had been isolated from Wuhan and reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) and other institutions;[8][83] the number of genomes increased to 42 by 30 January 2020.[84] A phylogenetic analysis of those samples showed they were "highly related with at most seven mutations relative to a common ancestor", implying that the first human infection occurred in November or December 2019.[84] As of 27 March 2020, 1,495 SARS-CoV-2 genomes sampled on six continents were publicly available.[85]

On 11 February 2020, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) announced that according to existing rules that compute hierarchical relationships among coronaviruses on the basis of five conserved sequences of nucleic acids, the differences between what was then called 2019-nCoV and the virus strain from the 2003 SARS outbreak were insufficient to make them separate viral species. Therefore, they identified 2019-nCoV as a strain of Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus.

Structural biology

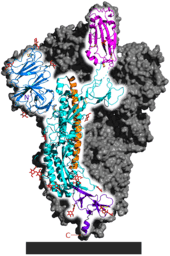

Each SARS-CoV-2 virion is approximately 50–200 nanometres in diameter.[58] Like other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 has four structural proteins, known as the S (spike), E (envelope), M (membrane), and N (nucleocapsid) proteins; the N protein holds the RNA genome, and the S, E, and M proteins together create the viral envelope.[86] The spike protein, which has been imaged at the atomic level using cryogenic electron microscopy,[87][88] is the protein responsible for allowing the virus to attach to and fuse with the membrane of a host cell.[86]

Protein modeling experiments on the spike protein of the virus soon suggested that SARS-CoV-2 has sufficient affinity to the receptor angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on human cells to use them as a mechanism of cell entry.[89] By 22 January 2020, a group in China working with the full virus genome and a group in the United States using reverse genetics methods independently and experimentally demonstrated that ACE2 could act as the receptor for SARS-CoV-2.[12][90][21][91] Studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 has a higher affinity to human ACE2 than the original SARS virus strain.[87][92] SARS-CoV-2 may also use basigin to assist in cell entry.[93]

Initial spike protein priming by transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) is essential for entry of SARS-CoV-2.[22] After a SARS-CoV-2 virion attaches to a target cell, the cell's protease TMPRSS2 cuts open the spike protein of the virus, exposing a fusion peptide. The virion then releases RNA into the cell and forces the cell to produce and disseminate copies of the virus, which infect more cells.[94]

SARS-CoV-2 produces at least three virulence factors that promote shedding of new virions from host cells and inhibit immune response.[86]

Epidemiology

.jpg)

Based on the low variability exhibited among known SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequences, the strain is thought to have been detected by health authorities within weeks of its emergence among the human population in late 2019.[18][95] The earliest case of infection currently known is thought to have been found on 17 November 2019.[96] The virus subsequently spread to all provinces of China and to more than 150 other countries in Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Oceania.[97] Human-to-human transmission of the virus has been confirmed in all of these regions.[98] On 30 January 2020, SARS-CoV-2 was designated a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the WHO,[10][99] and on 11 March 2020 the WHO declared it a pandemic.[9][100]

The basic reproduction number () of the virus has been estimated to be between 1.4 and 3.9.[101][102] This means that each infection from the virus is expected to result in 1.4 to 3.9 new infections when no members of the community are immune and no preventive measures are taken. The reproduction number may be higher in densely populated conditions such as those found on cruise ships.[103] Many forms of preventive efforts may be employed in specific circumstances in order to reduce the propagation of the virus.

There have been about 82,000 confirmed cases of infection in mainland China.[97] While the proportion of infections that result in confirmed cases or progress to diagnosable disease remains unclear,[104] one mathematical model estimated that on 25 January 2020 75,815 people were infected in Wuhan alone, at a time when the number of confirmed cases worldwide was only 2,015.[105] Before 24 February 2020, over 95% of all deaths from COVID-19 worldwide had occurred in Hubei province, where Wuhan is located.[106][107] As of 25 April 2020, the percentage had decreased to 1.6%.[97]

As of 25 April 2020, there have been 2,892,508 total confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the ongoing pandemic.[97] The total number of deaths attributed to the virus is 202,455.[97] Many recoveries from confirmed infections go unreported, but at least 815,658 people have recovered from confirmed infections.[97]

References

- Giaimo C (1 April 2020). "The Spiky Blob Seen Around the World". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus disease named Covid-19". BBC News Online. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Surveillance case definitions for human infection with novel coronavirus (nCoV): interim guidance v1, January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. January 2020. hdl:10665/330376. WHO/2019-nCoV/Surveillance/v2020.1.

- "Healthcare Professionals: Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "About Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Harmon A (4 March 2020). "We Spoke to Six Americans with Coronavirus". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "CoV2020". GISAID EpifluDB. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Wee SL, McNeil Jr. DG, Hernández JC (30 January 2020). "W.H.O. Declares Global Emergency as Wuhan Coronavirus Spreads". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, et al. (February 2020). "A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 514–523. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. PMC 7159286. PMID 31986261.

- Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. (February 2020). "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature. 579 (7798): 270–273. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. PMC 7095418. PMID 32015507.

- Perlman S (February 2020). "Another Decade, Another Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 760–762. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2001126. PMC 7121143. PMID 31978944.

- Benvenuto D, Giovanetti M, Ciccozzi A, Spoto S, Angeletti S, Ciccozzi M (April 2020). "The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (4): 455–459. doi:10.1002/jmv.25688. PMID 31994738.

- Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF (17 March 2020). "Correspondence: The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 22 (Report). World Health Organization. 11 February 2020. hdl:10665/330991.

- Shield C (7 February 2020). "Coronavirus: From bats to pangolins, how do viruses reach us?". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Cohen J (January 2020). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb0611.

- "Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19)". World Health Organization (WHO). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "How COVID-19 Spreads". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 27 January 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V (February 2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses". Nature Microbiology. 5 (4): 562–569. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PMC 7095430. PMID 32094589.

- Hoffman M, Kliene-Weber H, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, et al. (16 April 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor". Cell. 181 (2): 271–280.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. PMC 7102627. PMID 32142651.

- Huang P (22 January 2020). "How Does Wuhan Coronavirus Compare with MERS, SARS and the Common Cold?". NPR. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Fox D (24 January 2020). "What you need to know about the Wuhan coronavirus". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00209-y.

- Yam K (12 March 2020). "GOP lawmakers continue to use 'Wuhan virus' or 'Chinese coronavirus'". NBC News. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Marquardt A, Hansler J (26 March 2020). "US push to include 'Wuhan virus' language in G7 joint statement fractures alliance". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Wuhan virus sees Olympic football qualifiers moved". Xinhua. 22 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Rogers, Katie; Jakes, Lara; Swanson, Ana (18 March 2020). "Trump Defends Using 'Chinese Virus' Label, Ignoring Growing Criticism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Vazquez, Maegan. "Trump says he's pulling back from calling novel coronavirus the 'China virus'". CNN. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- McGurn, William (30 March 2020). "Opinion | Harvard's China Virus". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Aratani, Lauren (24 March 2020). "'Coughing while Asian': living in fear as racism feeds off coronavirus panic". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Vazquez, Marietta (12 March 2020). "Calling COVID-19 the "Wuhan Virus" or "China Virus" is inaccurate and xenophobic". Yale School of Medicine.

- WHO best practices for naming of new human infectious diseases (Report). World Health Organization. May 2015. hdl:10665/163636.

- Taylor-Coleman J (5 February 2020). "How the new coronavirus will finally get a proper name". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Hui M (18 March 2020). "Why won't the WHO call the coronavirus by its name, SARS-CoV-2?". Quartz. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

From a risk communications perspective, using the name SARS can have unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations.... For that reason and others, WHO has begun referring to the virus as "the virus responsible for COVID-19" or "the COVID-19 virus" when communicating with the public. Neither of these designations are [sic] intended as replacements for the official name of the virus as agreed by the ICTV.

- Li J, You Z, Wang Q, Zhou Z, Qiu Y, Luo R, et al. (March 2020). "The epidemic of 2019-novel-coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia and insights for emerging infectious diseases in the future". Microbes and Infection. 22 (2): 80–85. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.002. PMC 7079563. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Kessler, Glenn (17 April 2020). "Trump's false claim that the WHO said the coronavirus was 'not communicable'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Kuo, Lily (21 January 2020). "China confirms human-to-human transmission of coronavirus". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Edwards E (25 January 2020). "How does coronavirus spread?". NBC News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Getting your workplace ready for COVID-19" (PDF). World Health Organization. 27 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. (17 March 2020). "Correspondence: Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (16): 1564–1567. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004973. PMC 7121658. PMID 32182409.

- Yong E (20 March 2020). "Why the Coronavirus Has Been So Successful". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Gibbens S (18 March 2020). "Why soap is preferable to bleach in the fight against coronavirus". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. (March 2020). "First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (10): 929–936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. PMC 7092802. PMID 32004427.

- Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Müller MA, et al. (April 2020). "Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019". Nature: 1–10. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. PMID 32235945.

- Kupferschmidt K (February 2020). "Study claiming new coronavirus can be transmitted by people without symptoms was flawed". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb1524.

- To KK, Tsang OT, Leung W, Tam AR, Wu T, Lung DC, et al. (March 2020). "Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. PMC 7158907. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- World Health Organization (1 February 2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 12 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330777.

- Li R, Pei S, Chen B, Song Y, Zhang T, Yang W, et al. (16 March 2020). "Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2)". Science: eabb3221. doi:10.1126/science.abb3221. PMC 7164387. PMID 32179701. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- He X, Lau EH, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. (15 April 2020). "Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Questions and Answers on the COVID-19: OIE - World Organisation for Animal Health". www.oie.int. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Goldstein J (6 April 2020). "Bronx Zoo Tiger Is Sick with the Coronavirus". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "USDA Statement on the Confirmation of COVID-19 in a Tiger in New York". United States Department of Agriculture. 5 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- "If You Have Animals—Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 13 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Eschner K (28 January 2020). "We're still not sure where the Wuhan coronavirus really came from". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. (15 February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. (15 February 2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMC 7135076. PMID 32007143. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Cyranoski D (26 February 2020). "Mystery deepens over animal source of coronavirus". Nature. 579 (7797): 18–19. Bibcode:2020Natur.579...18C. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00548-w. PMID 32127703.

- Yu WB, Tang GD, Zhang L, Corlett RT (21 February 2020). "Decoding evolution and transmissions of novel pneumonia coronavirus using the whole genomic data". ChinaXiv. doi:10.12074/202002.00033 (inactive 28 March 2020). Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Forster P, Forster L, Renfrew C, Forster M (8 April 2020). "Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes" (PDF). PNAS. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "COVID-19: genetic network analysis provides 'snapshot' of pandemic origins". Cambridge University. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZC45, complete genome". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZXC21, complete genome". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Bat coronavirus isolate RaTG13, complete genome". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 10 February 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z (19 March 2020). "Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak". Current Biology. 30 (7): 1346–1351.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. PMC 7156161. PMID 32197085.

- Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 24 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. (February 2020). "Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding". The Lancet. 395 (10224): 565–574. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. PMC 7159086. PMID 32007145.

- Wu D, Wu T, Liu Q, Yang Z (12 March 2020). "The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: what we know". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 94: 44–48. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.004. ISSN 1201-9712. PMC 7102543. PMID 32171952.CS1 maint: display-authors (link)

- Paraskevis D, Kostaki EG, Magiorkinis G, Panayiotakopoulos G, Sourvinos G, Tsiodras S (April 2020). "Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel corona virus (2019-nCoV) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 79: 104212. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104212. PMC 7106301. PMID 32004758. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Liu P, Chen W, Chen JP (October 2019). "Viral Metagenomics Revealed Sendai Virus and Coronavirus Infection of Malayan Pangolins (Manis javanica)". Viruses. 11 (11): 979. doi:10.3390/v11110979. PMC 6893680. PMID 31652964.

- Cyranoski D (7 February 2020). "Did pangolins spread the China coronavirus to people?". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00364-2. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Xiao K, Zhai J, Feng Y (February 2020). "Isolation and Characterization of 2019-nCoV-like Coronavirus from Malayan Pangolins". bioRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.02.17.951335.

- Kelly G (1 January 2015). "Pangolins: 13 facts about the world's most hunted animal". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Gorman J (27 February 2020). "China's Ban on Wildlife Trade a Big Step, but Has Loopholes, Conservationists Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Jason Kindrachuk. "A Virologist Explains Why It Is Unlikely COVID-19 Escaped From A Lab". Forbes.com. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Wong MC, Cregeen SJ, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF (February 2020). "Evidence of recombination in coronaviruses implicating pangolin origins of nCoV-2019". bioRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.02.07.939207.

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. (February 2020). "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 727–733. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. PMC 7092803. PMID 31978945.

- "Phylogeny of SARS-like betacoronaviruses". nextstrain. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Wong AC, Li X, Lau SK, Woo PC (February 2019). "Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses". Viruses. 11 (2): 174. doi:10.3390/v11020174. PMC 6409556. PMID 30791586.

- Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D (9 March 2020). "Structure, function and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein". Cell. 181 (2): 281–292.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. PMC 7102599. PMID 32155444.CS1 maint: display-authors (link)

- "Initial genome release of novel coronavirus". Virological. 11 January 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Bedford T, Neher R, Hadfield N, Hodcroft E, Ilcisin M, Müller N. "Genomic analysis of nCoV spread: Situation report 2020-01-30". nextstrain.org. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.CS1 maint: display-authors (link)

- Bell SM, Müller N, Hodcroft E, Wagner C, Hadfield J, Ilcisin M, et al. "Genomic analysis of COVID-19 spread: Situation report 2020-03-27". nextstrain.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Wu C, Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang P, Zhong W, Wang Y, et al. (February 2020). "Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods". Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. PMC 7102550. PMID 32292689.

- Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, et al. (February 2020). "Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation". Science. 367 (6483): 1260–1263. Bibcode:2020Sci...367.1260W. doi:10.1126/science.abb2507. PMC 7164637. PMID 32075877.

- Mandelbaum RF (19 February 2020). "Scientists Create Atomic-Level Image of the New Coronavirus's Potential Achilles Heel". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, Feng J, Zhou H, Li X, et al. (March 2020). "Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission". Science China Life Sciences. 63 (3): 457–460. doi:10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. PMC 7089049. PMID 32009228.

- Letko M, Munster V (January 2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for lineage B β-coronaviruses, including 2019-nCoV". bioRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.01.22.915660.

- El Sahly HM. "Genomic Characterization of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Novel coronavirus structure reveals targets for vaccines and treatments". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2 March 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Wang K, Chen W, Zhou YS, Lian JQ, Zhang Z, Du P, et al. (14 March 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 invades host cells via a novel route: CD147-spike protein". bioRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.03.14.988345.

- "Anatomy of a Killer: Understanding SARS-CoV-2 and the drugs that might lessen its power". The Economist. 12 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Oberholzer M, Febbo P (19 February 2020). "What We Know Today about Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and Where Do We Go from Here". Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Ma J (13 March 2020). "Coronavirus: China's first confirmed Covid-19 case traced back to November 17". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)". ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 69 (Report). World Health Organization. 29 March 2020. hdl:10665/331615.

- "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- McKay B, Calfas J, Ansari T (11 March 2020). "Coronavirus Declared Pandemic by World Health Organization". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. (January 2020). "Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (13): 1199–1207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. PMC 7121484. PMID 31995857.

- Riou J, Althaus CL (January 2020). "Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020". Eurosurveillance. 25 (4). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.4.2000058. PMC 7001239. PMID 32019669.

- Rocklöv J, Sjödin H, Wilder-Smith A (February 2020). "COVID-19 outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: estimating the epidemic potential and effectiveness of public health countermeasures". Journal of Travel Medicine. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa030. PMC 7107563. PMID 32109273.

- Branswell H (30 January 2020). "Limited data on coronavirus may be skewing assumptions about severity". STAT. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM (February 2020). "Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study". The Lancet. 395 (10225): 689–697. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. PMC 7159271. PMID 32014114.

- Boseley S, McCurry J (30 January 2020). "Coronavirus deaths leap in China as countries struggle to evacuate citizens". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Paulinus A (25 February 2020). "Coronavirus: China to repay Africa in safeguarding public health". The Sun. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

Further reading

- Bar-On YM, Flamholz A, Phillips R, Milo R (31 March 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers". eLife. 9. arXiv:2003.12886. Bibcode:2020arXiv200312886B. doi:10.7554/eLife.57309. PMID 32228860.

- Brüssow H (March 2020). "The Novel Coronavirus – A Snapshot of Current Knowledge". Microbial Biotechnology. 2020 (3): 607–612. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13557. PMC 7111068. PMID 32144890.

- Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R (January 2020). "Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19)". StatPearls. PMID 32150360. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Habibzadeh P, Stoneman EK (February 2020). "The Novel Coronavirus: A Bird's Eye View". The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 11 (2): 65–71. doi:10.15171/ijoem.2020.1921. PMID 32020915.

- "Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in suspected human cases" (Report). World Health Organization. 2 March 2020. hdl:10665/331329.

External links

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020.

- "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic". World Health Organization (WHO).

- "SARS-CoV-2 (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) Sequences". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- "COVID-19 Resource Centre". The Lancet.

- "Coronavirus (Covid-19)". The New England Journal of Medicine.

- "Covid-19: Novel Coronavirus Outbreak". Wiley.

- "SARS-CoV-2". Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource.

- "SARS-CoV-2 related protein structures". Protein Data Bank.

| Classification |

|---|

.jpg)