SPQR

SPQR, an abbreviation for Senātus Populusque Rōmānus (Classical Latin: [sɛˈnaːtʊs pɔpʊˈlʊskᶣɛ roːˈmaːnʊs]; English: "The Roman Senate and People"; or more freely "The Senate and People of Rome"), is an emblematic abbreviated phrase referring to the government of the ancient Roman Republic. It appears on Roman currency, at the end of documents made public by an inscription in stone or metal, and in dedications of monuments and public works.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of ancient Rome |

| Periods |

|

| Roman Constitution |

|

| Precedent and law |

|

| Assemblies |

|

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

|

| Titles and honours |

|

|

The full phrase appears in Roman political, legal, and historical literature, such as the speeches of Cicero and Ab Urbe Condita Libri ("Books from the Founding of the City") of Livy.

Translation

SPQR: Senātus Populusque Rōmānus. In Latin, Senātus is a nominative singular noun meaning "Senate". Populusque is compounded from the nominative noun Populus, "the People", and -que, an enclitic particle meaning "and" which connects the two nominative nouns. The last word, Rōmānus ("Roman") is an adjective modifying the whole of Senātus Populusque: the "Roman Senate and People", taken as a whole. Thus, the phrase is translated literally as "The Roman Senate and People", or more freely as "The Senate and People of Rome".

Historical context

The title's date of establishment is unknown, but it first appears in inscriptions of the Late Republic, from c. 80 BC onwards. Previously, the official name of the Roman state, as evidenced on coins, was simply ROMA. The abbreviation last appears on coins of Constantine the Great (ruled 312–337 AD), the first Roman emperor to support Christianity.

The two legal entities mentioned, Senātus and the Populus Rōmānus, are sovereign when combined. However, where populus is sovereign alone, Senātus is not. Under the Roman Kingdom, neither entity was sovereign. The phrase, therefore, can be dated to no earlier than the foundation of the Republic.

This signature continued in use under the Roman Empire. The emperors were considered the de jure representatives of the people even though the senātūs consulta, or decrees of the Senate, were made at the de facto pleasure of the emperor.

Populus Rōmānus in Roman literature is a phrase meaning the government of the People. When the Romans named governments of other countries, they used populus in the singular or plural, such as populī Prīscōrum Latīnōrum, "the governments of the Old Latins". Rōmānus is the established adjective used to distinguish the Romans, as in cīvis Rōmānus, "Roman citizen".

The Roman people appear very often in law and history in such phrases as dignitās, maiestās, auctoritās, lībertās populī Rōmānī, the "dignity, majesty, authority, freedom of the Roman people". They were a populus līber, "a free people". There was an exercitus, imperium, iudicia, honorēs, consulēs, voluntās of this same populus: "the army, rule, judgments, offices, consuls and will of the Roman people". They appear in early Latin as Popolus and Poplus, so the habit of thinking of themselves as free and sovereign was quite ingrained.

The Romans believed that all authority came from the people. It could be said that similar language seen in more modern political and social revolutions directly comes from this usage. People in this sense meant the whole government. The latter, however, was essentially divided into the aristocratic Senate, whose will was executed by the consuls and praetors, and the comitia centuriāta, "committee of the centuries", whose will came to be safeguarded by the Tribunes.

One of the ways the emperor Commodus (180–192) paid for his donatives and mass entertainments was to tax the senatorial order, and on many inscriptions, the traditional order is provocatively reversed (Populus Senatusque...).

Beginning in 1184, the Commune of Rome struck coins in the name of the SENATVS P Q R. From 1414 until 1517, the Roman Senate struck coins with a shield inscribed SPQR.[1]

During the regime of Benito Mussolini, SPQR was emblazoned on a number of public buildings and manhole covers in an attempt to promote his dictatorship as a "New Roman Empire".

Modern use

Even in contemporary usage, SPQR is still used in the municipal coat of arm of Rome and as abbreviation for the comune of Rome in official documents.[2][3]

Civic references

SPQx is sometimes used as an assertion of municipal pride and civic rights. The Italian town of Reggio Emilia, for instance, has SPQR in its coat of arms, standing for "Senatus Populusque Regiensis". There have been confirmed usages and reports of the deployment of the "SPQx" template in;

- Alkmaar, Netherlands, SPQA on the facade of the Waag building, now cheese museum.

- Amsterdam, Netherlands, SPQA at one of the major theatres and some of the bridges[4]

- Antwerp, Belgium, SPQA on the Antwerp City Hall[5]

- Basel, Switzerland, SPQB on the Webern-Brunnen in Steinenvorstadt[6]

- Benevento, Italy, SPQB on manhole covers[7]

- Bremen, Germany, SPQB in the Bremen City Hall[8]

- Bruges, Belgium, SPQB on its coat of arms[9]

- Brussels, Belgium, SPQB found repeatedly on the Palais de Justice,[10] and over the main stage of La Monnaie

- Capua, Italy, SPQC

- Catania, Italy, SPQC can be found on manhole covers

- Chicago, United States, SPQC can be found on the George N. Leighton Cook County Criminal Courthouse

- Dublin, Ireland, SPQH on the City Hall, built in 1769

- Florence, Italy, SPQF[7]

- Franeker, Netherlands, SPQF, At the a gate on the Westerbolwerk and Academiestraat 16.[11]

- Freising, Germany, SPQF, above the door of the town hall.

- Ghent, Belgium, SPQG on the Opera, Theater and some other major buildings. In 1583, during the Dutch Revolt, Ghent struck coins with a shield inscribed SPQG.[12]

- The Hague, Netherlands, SPQH above the stage in Koninklijke Schouwburg

- Hamburg, Germany, SPQH on a door in the Hamburg Rathaus[13]

- Hanover, Germany

- Haarlem, the Netherlands, SPQH on the face of the town hall at the "Grote Markt"

- Hasselt, Belgium, SPQH

- Kortrijk, Belgium, SPQC, city hall

- La Plata, Argentina, SPQR in a monument outside of the city's "casco urbano".

- Leeuwarden, Netherlands, SPQL on the mayor's chain of office[14]

- Liverpool, England, SPQL on various gold doors in St George's Hall[15]

- City of London, England, SPQL[16][17]

- Lübeck, Germany, SPQL on the Holstentor[18]

- Lucerne, Switzerland

- Milan, Italy, The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V struck coins at Milan with the inscription S P Q MEDIOL OPTIMO PRINCIPI.[19]

- Modica, Italy, SPQM is on the coat of arms

- Molfetta, Italy, SPQM is on the coat of arms[20]

- Naples, Italy, Coins struck during Masaniello’s 1647 revolt showed a shield inscribed SPQN.[21]

- Noto, Italy, SPQN on the coat of arms and the façade of Noto Cathedral

- Nuremberg, Germany, SPQN ("Norimbergensis") on the Fleisch Bridge (one of the major bridges over river Pegnitz in the inner city)

- Oudenburg, Belgium, SPQO (Senatus Populusque Odenburgensis) on its water pump next to the market square.[22]

- Olomouc, Czech Republic, SPQO on its coat of arms[7]

- Palermo, Italy, SPQP[23]

- Penne, Abruzzo, Italy, SPQP[23]

- Rieti, Italy, SPQS on the coat of arms (the second "S" stands for "Sabinus", referring to the Sabines). Present also in the modern composite Lazio coat-of-arms.

- Rotterdam, the Netherlands, SPQR on a wallpainting in the Rotterdam City Hall

- Severn Beach, United Kingdom, SPQR on the Parish Council coat of arms.

- Siena, Italy, SPQS[24]

- Solothurn, Switzerland, SPQS on the Cathedral of St Ursus and Victor

- Terracina, Italy, SPQT[25]

- Tivoli, Lazio, Italy, SPQT[26]

- Valencia, Spain, SPQV in several places and buildings, including the Silk Exchange[27] and the University of Valencia[28] Historic Building.

- Verviers, Belgium, SPQV on the Grand Theatre[29]

- Vienna, Austria[7]

Use by white supremacists

Some members of white supremacist groups use the acronym SPQR on flags, on their person (such as tattoos) and other forms of identification.[30][31][32][33] The movement's enthusiasm for other symbols of republican Rome, such as the axe and bundled rods known as fasces, is documented, as well as their interest in some aspects of republican and imperial Rome.[34] That use was discussed on Stormfront's bulletin boards and was noticed at white supremacist demonstrations.[31] White supremacists tend to associate "SPQR" with the militaristic ethos of the Roman legions. There is in fact no evidence that the initialism appeared regularly on Roman military insignia and equipment, but it was heavily used by Mussolini's fascist regime.[32]

Popular culture

- The Italians have long used a different and humorous expansion of this abbreviation, "Sono Pazzi Questi Romani" (literally: "They're crazy, these Romans").[35] In the Asterix and Obelix comics, Obelix often uses the French translation of this phrase, "Ils sont fous ces Romains", and in the Italian editions, the original phrase is used.[36]

- In the early twentieth century, the letters "SPQR" could sometimes be seen displayed on London market traders' stalls, meaning "Small Profits, Quick Returns".[37]

- S.P.Q.R. Records was an American popular music record label, a subsidiary of Legrand Records, which flourished in the 1960s and included Gary U.S. Bonds among its artists. The label was founded by Frank Guida, who is believed to have adopted the name in allusion to his Italian origins.[38]

- S.P.Q.R. is the fourth song on the critically acclaimed experimental rock album Deceit (1981) by This Heat. The song talks about atomic destruction and human morals using symbols of Rome.[39]

- S.P.Q.R. is a restaurant in Ponsonby, Auckland, New Zealand, opened in 1992,[40] and a finalist in the Metro Peugeot Restaurant of the Year 2019 awards.[41]

- MPQN, standing for Metallica Populusque Nimus, appears on the cover of the Metallica live DVD Français Pour une Nuit (2009), which was recorded in the Arena of Nîmes, a remodelled Roman amphiteatre.[42]

- In Rick Riordan's fantasy series The Heroes of Olympus (2010–2014), the Roman Camp Jupiter tattoos SPQR on legionnaires' arms.

Gallery

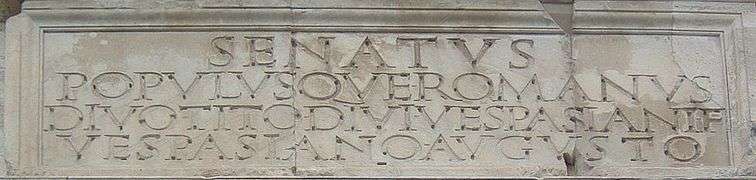

The inscription in the Arch of Titus

The inscription in the Arch of Titus- Manhole cover in Rome with SPQR inscription

SPQR in the coat of arms of Reggio Emilia

SPQR in the coat of arms of Reggio Emilia Detail from the mosaic floor in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan

Detail from the mosaic floor in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan.jpg) "Superiority of the warrior class. State 2." Etching by Wenceslaus Hollar, (University of Toronto)

"Superiority of the warrior class. State 2." Etching by Wenceslaus Hollar, (University of Toronto)- Arch of Septimius Severus top inscription

Dedicatory plaque to Federico Fellini on Via Veneto

Dedicatory plaque to Federico Fellini on Via Veneto Mural in the Burgerzaal of Rotterdam City Hall

Mural in the Burgerzaal of Rotterdam City Hall

References

- Monete e Zecche Medievalli Italiane, Elio Biaggi, coins 2081 and 2141

- "Roma Capitale - Sito Istituzionale - Home" (in Italian). Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "OGGETTO: Revoca deleghe Consigliera Nathalie Naim" (PDF) (in Italian). S.P.Q.R. - ROMA CAPITALE - MUNICIPIO ROMA CENTRO STORICO. 2 February 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Heraldic symbols of Amsterdam, Livius.org, 2 December 2006.

- "Flickr.com". Flickr.com. 5 January 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "brunnenfuehrer.ch". 1 January 2003. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- "Rome - Historical Flags (Italy)", CRWflags.com, 14 November 2003.

- "Unesco.org" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "NGW.nl". NGW.nl. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "Eupedia.com". Eupedia.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "Franeker". www.gevelstenen.net.

- Coinage of the European Continent, W. Carew Hazlitt, page 216.

- (in German) Nefershapiland.de

- (in Dutch) Gemeentearchief.nl

- St George's HallBy Paul Coslett. "BBC.co.uk". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- Cityoflondon.gov.uk Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Brunet, Alex. (2013). pp. 156-7. Regal Armorie of Great Britain. London: Forgotten Books. (Original work published 1839)

- "Flickr.com". Flickr.com. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- The Coinage of Milan, W.. J. Potter, page 19 coin 4.

- it:File:Molfetta-Stemma.png

- Italian Coinage Medieval to Modern, The Collection of Ercole Gnecchi, coin 3683

- "Stadspomp, Oudenburg".

- "Flickr.com". Flickr.com. 5 December 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "Flickr.com". Flickr.com. 17 June 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- O. A. W. Dilke and Margaret S. Dilke (October 1961). "Terracina and the Pomptine Marshes". Greece & Rome. Cambridge University Press. II:8 (2): 172–178. ISSN 0017-3835. OCLC 51206579.

- "Tibursuperbum.it". Tibursuperbum.it. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes". Cervantesvirtual.com. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- http://farm4.staticflickr.com/3020/2927782582_9812c8d395_s.jpg

- (in French) Bestofverviers.be

- Bond, Sarah E. (30 August 2018). "The misuse of an ancient Roman acronym by white nationalist groups". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Angell, Ben; et al. (27 July 2018). "Scholars Respond to SPQR and White Nationalism". Pharos. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Angell, Ben; et al. (15 June 2018). "SPQR and White Nationalism". Pharos. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Flags and Other Symbols Used By Far-Right Groups in Charlottesville". Southern Poverty Law Center. 12 August 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Angell, Ben; et al. (11 December 2017). ""American Fascist Manifesto" begins with the Roman Republic". Pharos. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- See, e.g. von Hefner, Otto Titan (1861). Handbuch der theoretischen und praktischen Heraldik. Munich. p. 106.

- Asterix around the world

- Fowler, H. W.; Fowler, F. G.; Crystal, David (2011) [1911]. The Concise Oxford Dictionary: The Classic First Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 748. ISBN 978-0-19-969612-3.

- "Biography – S.P.Q.R." 45cat.com. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "This Heat – S.P.Q.R."

- King, Helen (28 October 2017). "Iconic Auckland restaurant SPQR up for sale". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "SPQR restaurant review: Metro Top 50 2019". Metro. 1 May 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Cover of Français Pour Une Nuit - Live Aux Arènes De Nîmes 2009 at Discogs

- "'SPQR' adds final touch to special derby kit". www.asroma.com.

Further reading

- Beneš, Carrie E. (2009). "Whose SPQR? Sovereignty and semiotics in medieval Rome". Speculum. 84 (4): 874–904. doi:10.1017/s0038713400208130.

- Moatti, Claudia (2017). "Res publica, forma rei publicae, and SPQR". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies of the University of London. 60 (1): 34–48. doi:10.1111/2041-5370.12046.

External links

| Library resources about SPQR |

| Look up SPQR in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to SPQR. |

- Instances of "Roman Senate and People" in www.Perseus.edu

- Lewis & Short dictionary entry for populus on www.Perseus.edu

- Polybius on the Senate and People (6.16)

- SPQR street light lamp in Rome