Senate of Canada

The Senate of Canada (French: Sénat du Canada) is the upper house of the Parliament of Canada. The Senate is modelled after the British House of Lords and consists of 105 members appointed by the governor general on the advice of the prime minister.[1] Seats are assigned on a regional basis: four regions—defined as Ontario, Quebec, the Maritime provinces, and the Western provinces—each receives 24 seats, with the last nine seats allocated to the remaining portions of the country: six to Newfoundland and Labrador and one each to the three northern territories. Senators serve until they reach the mandatory retirement age of 75.

Senate of Canada Sénat du Canada | |

|---|---|

| 43rd Parliament | |

| Type | |

| Type | Upper House of the Parliament of Canada |

| Leadership | |

Speaker | |

Speaker Pro Tempore | vacant since January 21, 2020 |

Representative of the Government | Marc Gold since January 24, 2020 |

Senate Opposition Leader | |

Facilitator of the ISG | Yuen Pau Woo since September 25, 2017 |

Leader of the CSG (interim) | Scott Tannas since November 4, 2019 |

Leader of the PSG | Jane Cordy since December 12, 2019 |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 105 |

.svg.png) | |

Political groups |

|

| Elections | |

| Appointment by the Governor General on advice of the Prime Minister | |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Senate of Canada Building (temporary) 2 Rideau Street, Ottawa, Ontario | |

| Website | |

| sencanada | |

While the Senate is the upper house of parliament and the House of Commons is the lower house, this does not imply the former is more powerful than the latter. It merely entails that its members and officers outrank the members and officers of the Commons in the order of precedence for the purposes of protocol. As a matter of practice and custom, the Commons is the dominant chamber. The prime minister and Cabinet are responsible solely to the House of Commons and remain in office only so long as they retain the confidence of that chamber. Parliament is composed of the two houses together with the monarch (represented by the governor general).

The approval of both houses is necessary for legislation and, thus, the Senate can reject bills passed by the Commons. Between 1867 and 1987, the Senate rejected fewer than two bills per year, but this has increased in more recent years.[2] Although legislation can normally be introduced in either chamber, the majority of government bills originate in the House of Commons, with the Senate acting as the chamber of "sober second thought" (as it was called by Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada's first prime minister).[3]

History

The Senate came into existence in 1867, when the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the British North America Act 1867 (BNA Act), uniting the Province of Canada (which was separated into Quebec and Ontario) with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick into a single federation, the dominion of Canada. The Canadian parliament was based on the Westminster system (that is, the model of the Parliament of the United Kingdom). Canada's first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, described it as a body of "sober second thought" that would curb the "democratic excesses" of the elected House of Commons and provide regional representation.[4] He believed that if the House of Commons properly represented the population, the upper chamber should represent the regions.[5] It was not meant to be more than a revising body or a brake on the House of Commons. Therefore, it was deliberately made an appointed house, since an elected Senate might prove too popular and too powerful and be able to block the will of the House of Commons.

In 2008 the Canadian Heraldic Authority granted the Senate, as an institution, a coat of arms composed of a depiction of the chamber's mace (representing the monarch's authority in the upper chamber) behind the escutcheon of the Arms of Canada.[6]

| Modifying act | Date enacted | Normal total | §26 total | Ont. | Que. | Maritime Provinces | Western Provinces | N.L. | N.W.T. | Y.T. | Nu. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N.S. | N.B. | P.E.I. | Man. | B.C. | Sask. | Alta. | ||||||||||

| Constitution Act, 1867 | July 1, 1867 | 72 | 78 | 24 | 24 | 12 | 12 | |||||||||

| Manitoba Act, 1870 | July 15, 1870 | 74 | 80 | 24 | 24 | 12 | 12 | 2 | ||||||||

| British Columbia Terms of Union | July 20, 1871 | 77 | 83 | 24 | 24 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| Prince Edward Island Terms of Union as per §147 of the Constitution Act, 1867 | July 1, 1873 | 77 | 83 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Alberta Act and Saskatchewan Act | September 1, 1905 | 85 | 91 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Constitution Act, 1915 | May 19, 1915 | 96 | 104 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Newfoundland Act as per ¶1(1)(vii) of the Constitution Act, 1915 | March 31, 1949 | 102 | 110 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Constitution Act (No. 2), 1975 | June 19, 1975 | 104 | 112 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |

| Constitution Act, 1999 (Nunavut) | April 1, 1999 | 105 | 113 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Senate reform

Discussion of Senate reform dates back to at least 1874,[7] but to date there has been no meaningful change.[8]

In 1927, The Famous Five Canadian women asked the Supreme Court determine whether women were eligible to become senators. In the Persons Case, the court unanimously held that women could not become senators since they were not "persons". On appeal, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ruled that women were persons, and four months later, Cairine Wilson was appointed senator.

In the 1960s, discussion of reform appeared along with Quiet Revolution and the rise of Western alienation. The first change to the Senate was in 1965, when a mandatory retirement age of 75 years was set. Appointments made before then were for life.

In the 1970s the emphasis was on increased provincial involvement in the senators' appointments.[7] Since the '70s, there have been at least 28 major proposals for constitutional Senate reform, and all have failed,[9] including the 1987 Meech Lake Accord, and the 1992 Charlottetown Accord.

Starting in the 1980s, proposals were put forward to elect senators. After Parliament enacted the National Energy Program Western Canadians called for a Triple-E (elected, equal, and effective) senate.[10] In 1982 the Senate was given a qualified veto over certain constitutional amendments.[9] In 1987 Alberta legislated for the Alberta Senate nominee elections. Results of the 1989 Alberta Senate nominee election were non-binding.

Following the Canadian Senate expenses scandal Prime Minister Stephen Harper declared a moratorium on further appointments. Harper had advocated for an elected Senate for decades, but his proposals were blocked by a 2014 Supreme Court ruling[11] that requires a constitutional amendment approved by a minimum of seven provinces, whose populations together accounted for at least half of the national population.[12]

In 2014 Liberal leader Justin Trudeau expelled all senators from the Liberal caucus and, as prime minister in 2016, created the Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments,[13] both of which being attempts to make the Senate less partisan, without requiring constitutional change.[11] Members of the board include members from each jurisdiction where there is a vacancy.[14] The prime minister is not bound to accept the board's recommendation.[15] Some provinces refused to participate, stating that it would make the situation worse by lending the Senate some legitimacy.[16] Since this new appointments process was launched in 2016, 52 new senators, all selected under this procedure, were appointed to fill vacancies. All Canadians may now apply directly for a Senate appointment at any time, or nominate someone they believe meets the merit criteria.[17]

Chamber and offices

The original Senate chamber was lost to the fire that consumed the Parliament Buildings in 1916. The Senate then sat in the mineral room of what is today the Canadian Museum of Nature until 1922, when it relocated to Parliament Hill. With the Centre Block undergoing renovations, temporary chambers have been constructed in the Senate of Canada Building, where the Senate began meeting in 2019.[18]

There are chairs and desks on both sides of the chamber, divided by a centre aisle. A public gallery is above the chamber.

The dais of the Speaker is at one end of the chamber, and includes the new royal thrones, made in part from English walnut from Windsor Great Park.

Outside of Parliament Hill, most senators have offices in the Victoria Building across Wellington Street.

Senators

Appointment

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Canada |

| Government (structure) |

|

|

|

Legislative (Queen-in-Parliament)

|

|

Judicial (Queen-on-the-Bench)

|

|

Elections

|

|

Local government

|

|

Foreign relations

|

|

Related topics

|

|

Senators are appointed by the Governor General of Canada via recommendation of the prime minister. Traditionally members of the prime minister's own party were chosen. Constitutional requirements for appointment are:

- citizen of Canada

- between 30 and 75 years of age

- own property worth at least $4,000 above his or her debts and liabilities.[1] These were introduced to ensure senators were not beholden to economic vagaries and turmoil.

- resident of province or territory for which the person is appointed

Disqualification

- fails to attend two consecutive sessions of the Senate;

- becomes a subject or citizen of a foreign power;

- declares bankruptcy

- is convicted of treason or an indictable offence

- ceases to be qualified in respect of property or of residence (except where required to stay in Ottawa because they hold a government office).

- retirement is required at age 75.

Representation

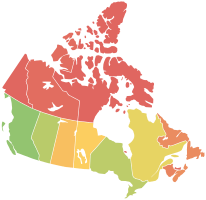

Each province or territory is entitled to a specific number of Senate seats. The constitution divides Canada into four areas, each with 24 senators: Ontario, Quebec, the Maritimes, and Western Canada. Newfoundland and Labrador is represented by six senators. The Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and Nunavut) are allocated one senator each. Quebec senators are the only ones to be assigned to specific districts within their province. This rule was adopted to ensure that both French- and English-speakers from Quebec were represented appropriately in the Senate.

Like most other upper houses worldwide, the Canadian formula does not use representation by population as a primary criterion for member selection, since this is already done for the House of Commons. Rather, the intent when the formula was struck was to achieve a balance of regional interests and to provide a house of "sober second thought" to check the power of the lower house when necessary. Therefore, the most populous province (Ontario) and two western provinces that were not populous at their accession to the federation and that are within a region are under-represented, while the Maritimes are the opposite. For example, British Columbia, with a population of about five million, sends six senators to Ottawa, whereas, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, with populations of fewer than one million, are each entitled to 10 senators. Only Quebec has a share of senators approximate to its share of the total population. For comparison, Canada has roughly one senator for about 300,000 citizens, while the United States Senate has one elected senator for about three million citizens.

A senator must possess land worth at least $4,000 in the province for which he or she is appointed. And are required to have residency in the provinces or territories for which they are appointed.[1] In the past, this criterion has often been interpreted quite liberally, with virtually any holding that met the property qualification, including primary residences, second residences, summer homes, investment properties or even lots of undeveloped land, having been deemed to meet the residency requirement;[19] as long as the senator listed a qualifying property as a residence, no further efforts have typically been undertaken to verify whether they actually resided there in any meaningful way.[19] Residency has come under increased scrutiny, particularly in 2013 as several senators have faced allegations of irregularities in their housing expense claims. Since 2016, the Government requires that appointees reside at least two years in the province or territory where they are being appointed, and appointees must provide supporting documentation.[20]

| Province or territory | Senate region | Senators | Population per senator (2017 est.) |

Total population (2017 est.) | % senators | % population | seats, House of Commons | % seats, Commons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 24 | 591,391 | 14,193,384 | 22.9% | 38.6% | 121 | 35.8% | |

| Quebec | 24 | 349,751 | 8,394,034 | 22.9% | 23.0% | 78 | 23.1% | |

| Western Canada | 6 | 802,860 | 4,817,160 | 5.7% | 13.1% | 42 | 12.4% | |

| 6 | 714,356 | 4,286,134 | 5.7% | 11.7% | 34 | 10.0% | ||

| 6 | 223,018 | 1,338,109 | 5.7% | 3.6% | 14 | 4.1% | ||

| 6 | 193,988 | 1,163,925 | 5.7% | 3.2% | 14 | 4.1% | ||

| Maritimes | 10 | 95,387 | 953,869 | 9.5% | 2.6% | 11 | 3.3% | |

| 10 | 75,966 | 759,655 | 9.5% | 2.1% | 10 | 3.0% | ||

| 4 | 38,005 | 152,021 | 3.8% | 0.4% | 4 | 1.2% | ||

| N/A | 6 | 88,136 | 528,817 | 5.7% | 1.5% | 7 | 2.1% | |

| 1 | 44,520 | 44,520 | 0.9% | 0.1% | 1 | 0.3% | ||

| 1 | 38,459 | 38,459 | 0.9% | 0.1% | 1 | 0.3% | ||

| 1 | 37,996 | 37,996 | 0.9% | 0.1% | 1 | 0.3% | ||

| Total/Average, |

105 | 334,681 | 36,708,083 | 100% | 100% | 338 | 100% | |

| Note: Population data based on the latest official 2016 Canadian Census, conducted and published by Statistics Canada.[21] | ||||||||

There exists a constitutional provision—Section 26 of the Constitution Act, 1867—under which the sovereign may approve the appointment of four or eight extra senators, equally divided among the four regions. The approval is given by the monarch on the advice of the prime minister, and the governor general is instructed to issue the necessary letters patent. This provision has been used only once: in 1990, when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney sought to ensure the passage of a bill creating the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The appointment of eight additional senators allowed a slight majority for the Progressive Conservative Party. There was one unsuccessful attempt to use Section 26, by Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie in 1874. It was denied by Queen Victoria, on the advice of the British Cabinet.[22] The clause does not result in a permanent increase in the number of Senate seats, however. Instead, an attrition process is applied by which senators leaving office through normal means are not replaced until after their province has returned to its normal number of seats.

Since 1989, the voters of Alberta have elected "senators-in-waiting", or nominees for the province's Senate seats. These elections, however, are not held pursuant to any federal constitutional or legal provision; thus, the prime minister is not required to recommend the nominees for appointment. Only three senators-in-waiting have been appointed to the Senate: the first was Stan Waters, who was appointed in 1990 on the recommendation of Brian Mulroney; the second was Bert Brown, elected a Senator-in-waiting in 1998 and 2004, and appointed to the Senate in 2007 on the recommendation of Prime Minister Stephen Harper; and the third was Betty Unger, elected in 2004 and appointed in 2012.[23]

The base annual salary of a senator was $150,600 in 2019.[24] and members may receive additional salaries in right of other offices they hold (for instance, the title of Speaker). Most senators rank immediately above Members of Parliament in the order of precedence, although the Speaker is ranked just above the Speaker of the House of Commons and both are a few ranks higher than the remaining senators.

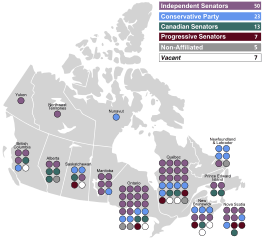

Current composition

| Caucus | Senators[25] | |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Senators Group[lower-alpha 2] | 50 | |

| Conservative | 21 | |

| Canadian Senators Group[lower-alpha 3] | 13 | |

| Non-affiliated | 7 | |

| Progressive Senate Group[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 1] | 6 | |

| Vacant | 8 | |

| Total | 105 | |

- Notes

- The PSG currently does not have official party status

- The ISG was recognized as a parliamentary group on December 2, 2016 and given equal standing to the two partisan caucuses on May 17, 2017.[26]

- This parliamentary group was founded on November 4, 2019, by eight senators from the Independent Senators Group, two from the Conservative Party of Canada's Senate caucus, and one non-affiliated senator.[27]

- On November 14, 2019, Senator Joseph Day announced that the Senate Liberal Caucus had been officially disbanded, with its complement of nine members—at the time—forming a brand new, non-partisan parliamentary group in the Progressive Senate Group. With this dissolution, the Senate of Canada has no Liberal members for the first time since Confederation in 1867.[28]

Vacancies

There is some debate as to whether there is any requirement for the Prime Minister to advise the governor general to appoint new senators to fill vacancies as they arise. Then-Opposition leader Tom Mulcair argued that there is no constitutional requirement to fill vacancies. Constitutional scholar Peter Hogg has commented that the courts "might be tempted to grant a remedy" if the refusal to recommend appointments caused the Senate to be diminished to such a degree that it could not do its work or serve its constitutional function.[29]

Vancouver lawyer Aniz Alani filed an application for judicial review of then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper's apparent refusal to advise the appointment of senators to fill existing vacancies, arguing that the failure to do so violates the Constitution Act, 1867.[30]

On July 24, 2015, Harper announced that he would not be advising the governor general to fill the 22 vacancies in the Senate, preferring that the provinces "come up with a plan of comprehensive reform or to conclude that the only way to deal with the status quo is abolition". He declined to say how long he would allow vacancies to accumulate.[31] Under Canada's constitution, senators are appointed by the governor general on the advice of the Prime Minister. If no such advice is forthcoming, according to constitutional scholar Adam Dodek, in "extreme cases, there is no question that the Governor General would be forced to exercise such power [of appointment] without advice".[32]

On December 5, 2015, the new Liberal government announced a new merit-based appointment process, using specific new criteria as to eligibility for the Senate. Independent applicants, not affiliated with any political party, will be approved by a new five-member advisory board (to be in place by year end), a reform that was intended to begin eliminating the partisan nature of the Senate.[33] At the time, there were 22 vacancies in the Senate. On April 12, 2016, seven new senators were sworn in, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's hand picked Representative of the Government in the Senate, Hon. Peter Harder.

A series of additional appointments were announced for October and November 2016 that would fill all vacancies. Once these senators are summoned, the independent non-aligned senators became more numerous than either of the party caucuses for the first time in the Upper House's history. The independent senator group also grew to include over half the total number of senators.

On December 12, 2018, the four remaining vacancies were filled in Nova Scotia, the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Ontario. With these appointments, the Senate had a full complement of Senators for the first time in over eight years.[34]

Since December 2018, additional senators have retired so that the Senate currently has slightly fewer than 105 members again.

Officers

The presiding officer of the Senate is the Speaker, who is appointed by the governor general on the advice of the prime minister.[35] The Speaker is assisted by a Speaker Pro Tempore ("Current Speaker"), who is elected by the Senate at the beginning of each parliamentary session. If the Speaker is unable to attend, the Speaker Pro Tempore presides instead. Furthermore, the Parliament of Canada Act authorizes the Speaker to appoint another senator to take his or her place temporarily. Muriel McQueen Fergusson was the Parliament of Canada's first female Speaker, holding the office from 1972 to 1974.[2]

The Speaker presides over sittings of the Senate and controls debates by calling on members to speak. If a senator believes that a rule (or standing order) has been breached, he or she may raise a point of order, on which the Speaker makes a ruling. However, the Speaker's decisions are subject to appeal to the whole Senate. When presiding, the Speaker remains impartial, though he or she still maintains membership in a political party. Unlike the Speaker of the House of Commons, the Speaker of the Senate does not hold a casting vote, but, instead, retains the right to vote in the same manner as any other. As of the 42nd Parliament, beginning on December 2015, Senator George Furey presides as Speaker of the Senate.

The senator responsible for steering legislation through the Senate is the Representative of the Government in the Senate, who is a senator selected by the prime minister and whose role is to introduce legislation on behalf of the government. The position was created in 2016 to replace the former position of Leader of the Government in the Senate. The opposition equivalent is the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, who is selected by his or her counterpart in the House of Commons, the Leader of the Opposition. However, if the Official Opposition in the Commons is a different party than the Official Opposition in the Senate (as was the case from 2011 to 2015), then the Senate party chooses its own leader.

Officers of the Senate who are not members include the Clerk, the Deputy Clerk, the Law Clerk, and several other clerks. These officers advise the Speaker and members on the rules and procedure of the Senate. Another officer is the Usher of the Black Rod, whose duties include the maintenance of order and security within the Senate chamber. The Usher of the Black Rod bears a ceremonial black ebony staff, from which the title "black rod" arises. This position is roughly analogous to that of Sergeant-at-Arms in the House of Commons, but the Usher's duties are more ceremonial in nature. The responsibility for security and the infrastructure lie with the Director General of Parliamentary Precinct Services.

Committees

The Parliament of Canada uses committees for a variety of purposes. Committees consider bills in detail and can make amendments. Other committees scrutinize various government agencies and ministries.

The largest of the Senate committees is the Committee of the Whole, which, as the name suggests, consists of all senators. The Committee of the Whole meets in the chamber of the Senate, but proceeds under slightly modified rules of debate. (For example, there is no limit on the number of speeches a Member may make on a particular motion.) The presiding officer is known as the chairman. The Senate may resolve itself into a Committee of the Whole for a number of purposes, including to consider legislation or to hear testimony from individuals. Nominees to be officers of parliament often appear before Committee of the Whole to answer questions with respect to their qualifications prior to their appointment.

The Senate also has several standing committees, each of which has responsibility for a particular area of government (for example, finance or transport). These committees consider legislation and conduct special studies on issues referred to them by the Senate and may hold hearings, collect evidence, and report their findings to the Senate. Standing committees consist of between nine and fifteen members each and elect their own chairmen.

| Senate standing committees[36] |

|---|

|

Special committees are appointed by the Senate on an ad hoc basis to consider a particular issue. The number of members for a special committee varies, but, the partisan composition would roughly reflect the strength of the parties in the whole Senate. These committees have been struck to study bills (e.g., the Special Senate Committee on Bill C-36 (the Anti-terrorism Act), 2001) or particular issues of concern (e.g., the Special Senate Committee on Illegal Drugs).

Other committees include joint committees, which include both members of the House of Commons and senators. There are currently two joint committees: the Standing Joint Committee on the Scrutiny of Regulations, which considers delegated legislation, and the Standing Joint Committee on the Library of Parliament, which advises the two Speakers on the management of the library. Parliament may also establish special joint committees on an ad hoc basis to consider issues of particular interest or importance.

Legislative functions

Although legislation may be introduced in either chamber, most bills originate in the House of Commons. Because the Senate's schedule for debate is more flexible than that of the House of Commons, the government will sometimes introduce particularly complex legislation in the Senate first.

In conformity with the British model, the Senate is not permitted to originate bills imposing taxes or appropriating public funds. Unlike in Britain but similar to the United States, this restriction on the power of the Senate is not merely a matter of convention but is explicitly stated in the Constitution Act, 1867. In addition, the House of Commons may, in effect, override the Senate's refusal to approve an amendment to the Canadian constitution; however, they must wait at least 180 days before exercising this override. Other than these two exceptions, the power of the two Houses of Parliament is theoretically equal; the approval of each is necessary for a bill's passage. In practice, however, the House of Commons is the dominant chamber of parliament, with the Senate very rarely exercising its powers in a manner that opposes the will of the democratically elected chamber. Although the Senate has not vetoed a bill from the House of Commons since 1939, minor changes proposed by the Senate to a bill are usually accepted by the House.[40]

The Senate tends to be less partisan and confrontational than the Commons and is more likely to come to a consensus on issues. It also often has more opportunity to study proposed bills in detail either as a whole or in committees. This careful review process is why the Senate is still today called the chamber of "sober second thought", though the term has a slightly different meaning than it did when used by John A. Macdonald. The format of the Senate allows it to make many small improvements to legislation before its final reading.

The Senate, at times, is more active at reviewing, amending, and even rejecting legislation. In the first 60 years after Confederation, approximately 180 bills were passed by the House of Commons and sent to the Senate that subsequently did not receive Royal Assent, either because they were rejected by the Senate or were passed by the Senate with amendments that were not accepted by the Commons. In contrast, fewer than one-quarter of that number of bills were lost for similar reasons in the sixty-year period from 1928 to 1987.[2] The late 1980s and early 1990s was a period of contention. During this period, the Senate opposed legislation on issues such as the 1988 free trade bill with the US (forcing the Canadian federal election of 1988) and the Goods and Services Tax (GST).[41] In the 1990s, the Senate rejected four pieces of legislation: a bill passed by the Commons restricting abortion (C-43),[42] a proposal to streamline federal agencies (C-93), a bill to redevelop the Lester B. Pearson airport (C-28), and a bill on profiting from authorship as it relates to crime (C-220). From 2000 to 2013, the Senate rejected 75 bills in total.[43]

In December 2010, the Senate rejected Bill C-311, involving greenhouse gas regulation that would have committed Canada to a 25% reduction in emissions by 2020 and an 80% reduction by 2050.[44] The bill was passed by all the parties except the Conservatives in the House of Commons and was rejected by the majority Conservatives in the Senate on a vote of 43 to 32.[45] The only session where actual debate on the bill took place was notable for unparliamentary language and partisan political rhetoric.[46]

Divorce and other private bills

Historically, before the passage of the Divorce Act in 1968, there was no divorce legislation in either Quebec or Newfoundland. The only way for couples to get divorced in these provinces was to apply to the federal parliament for a private bill of divorce. These bills were primarily handled by the Senate, where a special committee would undertake an investigation of a request for a divorce. If the committee found that the request had merit, the marriage would be dissolved by an Act of Parliament. A similar situation existed in Ontario before 1930. This function has not been exercised since 1968 as the Divorce Act provided a uniform statutory basis across Canada accessed through the court system.

However, though increasingly rare, private bills usually commence in the Senate and only upon petition by a private person (natural or legal). In addition to the general stages public bills must go through, private bills also require the Senate to perform some judicial functions to ensure the petitioner's request does not impair rights of other persons.

Investigate function

The Senate also performs investigative functions. In the 1960s, the Senate authored the first Canadian reports on media concentration with the Special Senate Subcommittee on Mass Media, or the Davey Commission,[47] since "appointed senators would be better insulated from editorial pressure brought by publishers"; this triggered the formation of press councils.[48] More recent investigations include the Kirby Commissions on health care (as opposed to the Romanow Commission) and mental health care by Senator Michael Kirby and the Final Report on the Canadian News Media in 2006.[49]

Relationship with Her Majesty’s Government

Unlike the House of Commons, the Senate has no effect in the decision to end the term of the prime minister or of the government. Only the Commons may force the prime minister to tender his resignation or to recommend the dissolution of Parliament and issue election writs, by passing a motion of no-confidence or by withdrawing supply. Thus, the Senate's oversight of the government is limited.

The Senate does however approve the appointment of certain officials and approves the removal of certain officials, in some cases only for cause, and sometimes in conjunction with the House of Commons, usually as a recommendation from the Governor in Council. Officers in this category include the Auditor General of Canada,[50] and the Senate must join in the resolution to remove the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada.[51]

Most Cabinet ministers are from the House of Commons. In particular, every prime minister has been a member of the House of Commons since 1896, with the exception of John Turner. Typically, the Cabinet includes only one senator: the Leader of the Government in the Senate. Occasionally, when the governing party does not include any members from a particular region, senators are appointed to ministerial positions in order to maintain regional balance in the Cabinet. The most recent example of this was on February 6, 2006, when Stephen Harper advised that Michael Fortier be appointed to serve as both a senator representing the Montreal region, where the minority government had no elected representation, and the Cabinet position of Minister of Public Works and Government Services. Fortier resigned his Senate seat to run (unsuccessfully) for a House of Commons seat in the 2008 general election.

Broadcasting

Unlike the House of Commons, proceedings of the Senate were historically not carried by CPAC, as the upper house long declined to allow its sessions to be televised. On April 25, 2006, Senator Hugh Segal moved that the proceedings of the Senate be televised;[52] the motion was referred to the Senate Standing Committee on Rules, Procedures and the Rights of Parliament for consideration; although the motion was approved in principle, broadcast of senate proceedings was not actually launched at that time apart from selected committee meetings.[53]

Full broadcast of Senate proceedings launched for the first time on March 18, 2019,[54] concurrently with the Senate's temporary relocation to the Senate of Canada Building.[53]

See also

- Lists of Canadian senators

- List of current Canadian senators

- Canadian Senate divisions

- Canadian Senate seating plan

- Procedural officers and senior officials of the parliament of Canada

- List of Canadian Senate appointments by Prime Minister

- Canadian Senate Page Program

- Canadian Senate expenses scandal

- Joint address

References

- Guida, Franco (2006). Canadian almanac & directory (159th ed.). Micromedia ProQuest. pp. 3–42. ISBN 1-895021-90-1.

- "THE CANADIAN SENATE IN FOCUS 1867–2001". The Senate of Canada. May 2001. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- "FAQs about the Senate of Canada". Government of Canada. 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- "The Canadian Senate in Focus". Parl.gc.ca. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- "How to legitimize Canada's Senate". Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- Canadian Heraldic Authority. "Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada > Senate of Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- Jack Stillborn (November 1992). "Senate Reform Proposals in Comparative Perspective" (PDF). Library of Parliament. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gilmore, Scott (March 22, 2018). "Kill the Senate". www.macleans.ca. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Joyal, Serge (July 2003). Protecting Canadian Democracy: The Senate You Never Knew. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2619-8.

- Makarenko, Jay (October 1, 2006). "Senate Reform in Canada". MapleLeafWeb. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- Macfarlane, Emmett. "Did the Supreme Court just kill Senate reform? - Macleans.ca". Maclean's. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Fekete, Jason (June 19, 2015). "How to solve a problem like the Senate". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Harris, Kathleen (December 3, 2015). "Liberal plan to pick 'non-partisan' senators draws quick criticism". CBC News. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- Office, Privy Council (July 7, 2016). "Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments: Mandate and members". Government of Canada. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Tasker, John Paul (January 19, 2016). "Senate advisory board named, 1st appointments expected within weeks". CBC News. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- "Christy Clark says Trudeau legitimizing unaccountable Senate, B.C. under-representation". CBC. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- "Chantal Peticlerc, Murray Sinclair among 7 new Trudeau-appointed senators". CBC News. March 18, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- Canada, Senate of (February 8, 2019). "The Senate of Canada Building". Senate of Canada. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- "Senator says she won't talk more about Sask. residency". CBC News. February 17, 2009.

- "Senators ordered to provide concrete proof of primary residence". Ottawa Citizen. January 31, 2013. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Population – Canada at a Glance, 2018". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- W.H. McConnell, Commentary on the British North America Act (Toronto: McMillan & Co., 1977), pp. 72–73.

- "Harper appoints 7 new senators". CBC News. January 6, 2012.

- "Indemnities, Salaries and Allowances". Parliament of Canada. Library of Parliament. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- The Senate Chamber (PDF). Senate of Canada. February 19, 2019. pp. 1–2. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Tasker, John Paul (May 17, 2017). "Senate changes definition of a 'caucus,' ending Liberal, Conservative duopoly". CBC News. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- Flanagan, Ryan (November 14, 2019). "11 senators break away to form new Canadian Senators Group". CTV News. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Tasker, John Paul (J.P.) (November 14, 2019). "There's another new faction in the Senate: the Progressive Senate Group". CBC News. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- –"Stephen Harper obliged to fill empty Senate seats?". CBC News. July 10, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- –"Stephen Harper's unappointed Senate seats unconstitutional, Vancouver lawyer says". CBC News. December 15, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- Chase, Stephen (May 11, 2018). "Harper not planning to appoint more senatoTrs despite growing vacancies". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- Adam Dodek, "PM's constitutional disobedience a dangerous game to play", The Globe and Mail, July 28, 2015.

- Harris, Kathleen (December 3, 2015). "Liberal plan to pick 'non-partisan' senators draws quick criticism B.C. Premier Christy Clark slams reforms". CBC News. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- Tasker, John Paul (December 12, 2018). "Trudeau names four new senators – including a failed Liberal candidate". CBC News.

- "The Speaker of the Senate: Role and Appointment". Government of Canada. 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- "Senate – Committee List". Parl.gc.ca. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- "Senate – Committee Home Page". Parl.gc.ca. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- "Senate – Committee Home Page". Parl.gc.ca. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- "Senate – Committee Home Page". Parl.gc.ca. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- Foot, Richard. "Senate of Canada".

- Gibson, Gordon (September 2004). "Challenges in Senate Reform: Conflicts of Interest, Unintended Consequences, New Possibilities". Public Policy Sources. Fraser Institute. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- "Mulroney-era cabinet documents reveal struggle to replace abortion law thrown out by court". Toronto Star.

- "House of Commons bills sent to the Senate that did not receive Royal Assent". parl.gc.ca. November 16, 2010. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- "Senate vote to kill Climate Act disrespects Canadians and democracy". davidsuzuki.org. October 19, 2010. Archived from the original on May 3, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- "Debates of the Senate, November 16, 2010". Senate of Canada.

- "Debates of the Senate, June 1, 2010". Senate of Canada.

- "Concentration of Newspaper Ownership". Canadian Heritage. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- Edge, Marc (November 13, 2007). "Aspers and Harper, A Toried Love". The Tyee. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- "Concentration of Newspaper Ownership". Standing Senate Committee on Transport and Communications. June 2006. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- http://oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/au_fs_e_370.html

- Canada. "Appointment of the Chief Electoral Officer". Elections Canada. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- "Segal calls for televised Senate: Kingston politician wants body to be accountable". Kingston Whig-Standard, April 8, 2006.

- "Senate expected to start regular TV broadcasts after move to Government Conference Centre". iPolitics, March 10, 2018.

- "Ready for their closeup: Senate begins broadcasting proceedings for first time today". CBC News, March 18, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Senate of Canada. |

| Look up red chamber in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |