Samson

Samson (/ˈsæmsən/; שִׁמְשׁוֹן, Shimshon, "man of the sun")[1][lower-alpha 1] was the last of the judges of the ancient Israelites mentioned in the Book of Judges in the Hebrew Bible (chapters 13 to 16) and one of the last of the leaders who "judged" Israel before the institution of the monarchy. He is sometimes considered to be an Israelite version of the popular Near Eastern folk hero also embodied by the Sumerian Enkidu and the Greek Heracles.[2]

Samson | |

|---|---|

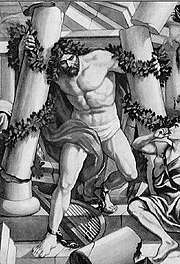

Samson's Fight with the Lion (1525) by Lucas Cranach the Elder | |

| Resting place | Tel Tzora, Brook of Sorek |

| Predecessor | Abdon |

| Successor | Eli |

| Parents |

|

| שופטים Judges in the Bible |

|---|

| Italics indicate individuals not explicitly described as judges |

| Pentateuch |

| Book of Joshua |

| Book of Judges |

| First Book of Samuel |

|

The biblical account states that Samson was a Nazirite, and that he was given immense strength to aid him against his enemies and allow him to perform superhuman feats,[3] including slaying a lion with his bare hands and massacring an entire army of Philistines using only the jawbone of a donkey. However, if Samson's long hair were cut, then his Nazirite vow would be violated and he would lose his strength.[4]

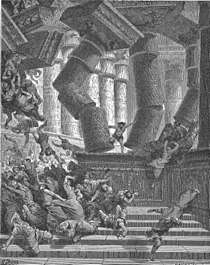

Samson was betrayed by his lover Delilah, who ordered a servant to cut his hair while he was sleeping and turned him over to his Philistine enemies, who gouged out his eyes and forced him to grind grain in a mill at Gaza. While there, his hair began to regrow. When the Philistines took Samson into their temple of Dagon, Samson asked to rest against one of the support pillars. After being granted permission, he prayed to God and miraculously recovered his strength, allowing him to bring down the columns, collapsing the temple and killing himself as well as all of the Philistines. In some Jewish traditions, Samson is believed to have been buried in Tel Tzora in Israel overlooking the Sorek valley.

Samson has been the subject of both rabbinic and Christian commentary, with some Christians viewing him as a type of Jesus, based on similarities between their lives. Notable depictions of Samson include John Milton's closet drama Samson Agonistes and Cecil B. DeMille's 1949 Hollywood film Samson and Delilah. Samson also plays a major role in Western art and traditions.

Biblical narrative

Birth

According to the account in the Book of Judges, Samson lived during a time of repeated conflict between Israel and Philistia, when God was disciplining the Israelites by giving them "into the hand of the Philistines".[5] Manoah was an Israelite from Zorah, descended from the Danites,[6] and his wife had been unable to conceive.[7][8] The Angel of the Lord appeared to Manoah's wife and proclaimed that the couple would soon have a son who would begin to deliver the Israelites from the Philistines.[9]

The Angel of the Lord stated that Manoah's wife was to abstain from all alcoholic drinks, unclean foods, and her promised child was not to shave or cut his hair. He was to be a Nazirite from birth. In ancient Israel, those wanting to be especially dedicated to God for a time could take a Nazirite vow which included abstaining from wine and spirits, not cutting hair or shaving, and other requirements.[7][8][9] Manoah's wife believed the Angel of the Lord; her husband was not present, so he prayed and asked God to send the messenger once again to teach them how to raise the boy who was going to be born.

After the Angel of the Lord returned, Manoah asked him his name, but he said, "Why do you ask my name? It is beyond understanding."[10] Manoah then prepared a sacrifice, but the Angel of the Lord would only allow it to be for God. He touched it with his staff, miraculously engulfing it in flames, and then ascended into the sky in the fire. This was such dramatic evidence of the nature of the Messenger that Manoah feared for his life, since it was said that no one could live after seeing God. However, his wife convinced him that, if God planned to slay them, he would never have revealed such things to them. In due time, their son Samson was born, and he was raised according to the Angel's instructions.[8][9]

Marriage to a Philistine

When he was a young adult, Samson left the hills of his people to see the cities of Philistia. He fell in love with a Philistine woman from Timnah, whom he decided to marry, ignoring the objections of his parents over the fact that she was non-Israelite.[8][9][11] In the development of the narrative, the intended marriage was shown to be part of God's plan to strike at the Philistines.[9]

According to the biblical account, Samson was repeatedly seized by the "Spirit of the Lord," who blessed him with immense strength. The first instance of this is seen when Samson was on his way to ask for the Philistine woman's hand in marriage, when he was attacked by a lion. He simply grabbed it and ripped it apart, as the spirit of God divinely empowered him. However, Samson kept it a secret, not even mentioning the miracle to his parents.[9][12][13] He arrived at the Philistine's house and became betrothed to her. He returned home, then came back to Timnah some time later for the wedding. On his way, Samson saw that bees had nested in the carcass of the lion and made honey.[9][13] He ate a handful of the honey and gave some to his parents.[9]

At the wedding feast, Samson told a riddle to his thirty groomsmen (all Philistines). If they could solve it, he would give them thirty pieces of fine linen and garments, but if they could not solve it, they would give him thirty pieces of fine linen and garments.[8][9] The riddle was a veiled account of two encounters with the lion, at which only he was present:[9][13]

Out of the eater came something to eat.

Out of the strong came something sweet.[14]

The Philistines were infuriated by the riddle.[9] The thirty groomsmen told Samson's new wife that they would burn her and her father's household if she did not discover the answer to the riddle and tell it to them.[9][13] At the urgent and tearful imploring of his bride, Samson told her the solution, and she told it to the thirty groomsmen.[8][9]

Before sunset on the seventh day they said to him,

What is sweeter than honey?

and what is stronger than a lion?

Samson said to them,

If you had not plowed with my heifer,

you would not have solved my riddle.[15]

Samson then traveled to Ashkelon (a distance of roughly 30 miles) where he slew thirty Philistines for their garments; he then returned and gave those garments to his thirty groomsmen.[8][13][16] In a rage, Samson returned to his father's house. The family of his would-have-been bride instead gave her to one of the groomsmen as wife.[8][13][16] Some time later, Samson returned to Timnah to visit his wife, unaware that she was now married to one of his former groomsmen. But her father refused to allow Samson to see her, offering to give Samson a younger sister instead.[8][16]

Samson went out, gathered 300 foxes, and tied them together in pairs by their tails. He then attached a burning torch to each pair of foxes' tails and turned them loose in the grain fields and olive groves of the Philistines.[17] The Philistines learned why Samson burned their crops and burned Samson's wife and father-in-law to death in retribution.[8][16][18]

In revenge, Samson slaughtered many more Philistines, saying, "I have done to them what they did to me."[8][16] Samson then took refuge in a cave in the rock of Etam.[8][16][19] An army of Philistines came to the Tribe of Judah and demanded that 3,000 men of Judah deliver them Samson.[8][19] With Samson's consent, given on the condition that the Judahites would not kill him themselves, they tied him with two new ropes and were about to hand him over to the Philistines when he broke free of the ropes.[18][19] Using the jawbone of a donkey, he slew 1,000 Philistines.[18][19][20]

Delilah

Later, Samson travels to Gaza, where he stays at a harlot's house.[16][21] His enemies wait at the gate of the city to ambush him, but he tears the gate from its very hinges and frame and carries it to "the hill that is in front of Hebron".[16][21]

He then falls in love with Delilah in the valley of Sorek.[16][18][21][22] The Philistines approach Delilah and induce her with 1,100 silver coins to find the secret of Samson's strength so that they can capture their enemy,[16][21] but Samson refuses to reveal the secret and teases her, telling her that he will lose his strength if he is bound with fresh bowstrings.[16][21] She does so while he sleeps, but when he wakes up he snaps the strings.[16][21] She persists, and he tells her that he can be bound with new ropes. She ties him up with new ropes while he sleeps, and he snaps them, too.[16][21] She asks again, and he says that he can be bound if his locks are woven into a weaver's loom.[16][21] She weaves them into a loom, but he simply destroys the entire loom and carries it off when he wakes.[16][21]

Delilah, however, persists and Samson finally capitulates and tells Delilah that God supplies his power because of his consecration to God as a Nazirite, symbolized by the fact that a razor has never touched his head, and that if his hair is cut off he will lose his strength.[23][24][16][22] Delilah then woos him to sleep "in her lap" and calls for a servant to cut his hair.[16] Samson loses his strength and he is captured by the Philistines who blind him by gouging out his eyes.[16] They then take him to Gaza, imprison him, and put him to work turning a large millstone and grinding grain.[21]

Death

One day, the Philistine leaders assemble in a temple for a religious sacrifice to Dagon, one of their most important deities, for having delivered Samson into their hands.[21][25] They summon Samson so that people can watch him perform for them. The temple is so crowded that people are even climbing onto the roof to watch—and all the rulers of the entire government of Philistia have gathered there too, some 3,000 people in all.[22][25][26] Samson is led into the temple, and he asks his captors to let him lean against the supporting pillars to rest. However, whilst in prison his hair had begun to grow again.[27] He prays for strength and God gives him strength to break the pillars, causing the temple to collapse, killing him and the people inside.[28]

After his death, Samson's family recovered his body from the rubble and buried him near the tomb of his father Manoah.[25] A tomb structure which some attribute to Samson and his father stands on the top of the mountain in Tel Tzora.[29] At the conclusion of Judges 16, it is said that Samson had "judged" Israel for twenty years.[19] The Bible does not mention the fate of Delilah.[22]

Interpretations

Rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature identifies Samson with Bedan,[8] a Judge mentioned by Samuel in his farewell address (1 Samuel 12:11) among the Judges who delivered Israel from their enemies.[30] However, the name "Bedan" is not found in the Book of Judges.[30] The name "Samson" is derived from the Hebrew word šemeš, which means "sun",[8][1][31] so that Samson bore the name of God, who is called "a sun and shield" in Psalms 84:11;[8] and as God protected Israel, so did Samson watch over it in his generation, judging the people even as did God.[8] Samson's strength was divinely derived (Talmud, Tractate Sotah 10a).[8][32]

Jewish legend records that Samson's shoulders were sixty cubits broad.[8] (Many Talmudic commentaries, however, explain that this is not to be taken literally, for a person that size could not live normally in society. Rather, it means that he had the ability to carry a burden 60 cubits wide (approximately 30 meters) on his shoulders).[33] He was lame in both feet[34] but, when the spirit of God came upon him, he could step with one stride from Zorah to Eshtaol, while the hairs of his head arose and clashed against one another so that they could be heard for a like distance.[8][35] Samson was said to be so strong that he could uplift two mountains and rub them together like two clods of earth,[35][36] yet his superhuman strength, like Goliath's, brought woe upon its possessor.[8][37]

In licentiousness, he is compared with Amnon and Zimri, both of whom were punished for their sins.[8][38] Samson's eyes were put out because he had "followed them" too often.[8][39] It is said that, in the twenty years during which Samson judged Israel, he never required the least service from an Israelite,[40] and he piously refrained from taking the name of God in vain.[8] Therefore, as soon as he told Delilah that he was a Nazarite of God, she immediately knew that he had spoken the truth.[8][39] When he pulled down the temple of Dagon and killed himself and the Philistines, the structure fell backward so that he was not crushed, his family being thus enabled to find his body and to bury it in the tomb of his father.[8][41]

In the Talmudic period, some seem to have denied that Samson was a historical figure, regarding him instead as a purely mythological personage. This was viewed as heretical by the rabbis of the Talmud, and they attempted to refute this. They named Hazelelponi as his mother in Numbers Rabbah Naso 10 and in Bava Batra 91a and stated that he had a sister named "Nishyan" or "Nashyan".[8]

Christian interpretations

Samson's story has also garnered commentary from a Christian perspective; the Epistle to the Hebrews praises him for his faith.[42] Ambrose, following the portrayal of Josephus and Pseudo-Philo,[43] represents Delilah as a Philistine prostitute,[43] and declares that "men should avoid marriage with those outside the faith, lest, instead of love of one's spouse, there be treachery."[43] Caesarius of Arles interpreted Samson's death as prefiguring the crucifixion of Jesus,[43] remarking: "Notice here an image of the cross. Samson extends his hands spread out to the two columns as to the two beams of the cross."[43] He also equates Delilah with Satan,[43] who tempted Christ.[43]

Following this trend, more recent Christian commentators have viewed Samson as a type of Jesus Christ, based on similarities between Samson's story and the life of Jesus in the New Testament.[44][45] Samson's and Jesus' births were both foretold by angels,[44] who predicted that they would save their people.[44] Samson was born to a barren woman,[44] and Jesus was born of a virgin.[44] Samson defeated a lion; Jesus defeated Satan, whom the First Epistle of Peter describes as a "roaring lion looking for someone to devour".[46] Samson's betrayal by Delilah has also been compared to Jesus' betrayal by Judas Iscariot;[45] both Delilah and Judas were paid in pieces of silver for their respective deeds.[47] Ebenezer Cobham Brewer notes in his A Guide to Scripture History: The Old Testament that Samson was "blinded, insulted [and] enslaved" prior to his death, and that Jesus was "blindfolded, insulted, and treated as a slave" prior to his crucifixion.[48] Brewer also compares Samson's death among "the wicked" with Christ being crucified between two thieves.[48]

Scholarly

Academics have interpreted Samson as a demigod (such as Heracles or Enkidu) enfolded into Jewish folklore,[49] or as an archetypical folk hero.[31]

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some comparative mythologists interpreted Samson as a euhemerized solar deity,[50][51][52][31] arguing that Samson's name is derived from Hebrew: šemeš, meaning "Sun",[31][1] and that his long hair might represent the Sun's rays.[31] These solar theorists also pointed out that the legend of Samson is set within the general vicinity of Beth Shemesh, a village whose name means "Temple of the Sun".[31] They argued that the name Delilah may have been a wordplay with the Hebrew word for night, layla, which "consumes" the day.[53] Although this hypothesis is still sometimes promoted in scholarly circles,[31] it has generally fallen out of favor due to the superficiality of supporting evidence.[31]

An interpretation far more popular among current scholars holds that Samson is a Hebrew variant of the same international Near Eastern folk hero which inspired the earlier Mesopotamian Enkidu and the later Greek Heracles (and, by extension, his Roman Hercules adaptation).[54][31][1] Heracles and Samson both slew a lion bare-handed (the former killed the Nemean lion).[31][1] Likewise, they were both believed to have once been extremely thirsty and drunk water which poured out from a rock,[54] and to have torn down the gates of a city.[54] They were both betrayed by a woman (Heracles by Deianira, Samson by Delilah),[31] who led them to their respective dooms.[31] Both heroes, champions of their respective peoples, die by their own hands:[31] Heracles ends his life on a pyre; whereas Samson makes the Philistine temple collapse upon himself and his enemies.[31] In this interpretation, the annunciation of Samson's birth to his mother is a censored account of divine conception.[54] Samson also strongly resembles Shamgar,[31] another hero mentioned in the Book of Judges,[31] who, in Judges 3:31, is described as having slain 600 Philistines with an ox-goad.[31]

These views are disputed by traditional and conservative biblical scholars who consider Samson to be a literal historical figure and thus reject any connections to mythological heroes.[31] The concept of Samson as a "solar hero" has been described as "an artificial ingenuity".[55] Joan Comay, co-author of Who's Who in the Bible: The Old Testament and the Apocrypha, The New Testament, believes that the biblical story of Samson is so specific concerning time and place that Samson was undoubtedly a real person who pitted his great strength against the oppressors of Israel.[56] In contrast, James King West considers that the hostilities between the Philistines and Hebrews appear to be of a "purely personal and local sort".[57] He also considers that Samson stories have, in contrast to much of Judges, an "almost total lack of a religious or moral tone".[57] Conversely, Elon Gilad of Haaretz writes "some biblical stories are flat-out cautions against marrying foreign women, none more than the story of Samson".[58] Gilad notes how Samson's parents disapprove of his desire to marry a Philistine woman and how Samson's relationship with Delilah leads to his demise.[58] He contrasts this with what he sees as a more positive portrayal of intermarriage in the Book of Ruth.[58]

Some academic writers have interpreted Samson as a suicide terrorist portrayed in a positive light by the text, and compared him to those responsible for the September 11 attacks.[59][60][61]

In August 2012, archaeologists from Tel Aviv University announced the discovery of a circular stone seal, approximately 15 mm (0.59 in) in diameter, which was found on the floor of a house at Beth Shemesh and appears to depict a long-haired man slaying a lion. The seal is dated to the 12th century BCE. According to Haaretz, "excavation directors Prof. Shlomo Bunimovitz and Dr. Zvi Lederman of Tel Aviv University say they do not suggest that the human figure on the seal is the biblical Samson. Rather, the geographical proximity to the area where Samson lived, and the time period of the seal, show that a story was being told at the time of a hero who fought a lion, and that the story eventually found its way into the biblical text and onto the seal."[62]

Cultural influence

As an important biblical character, Samson has been referred to in popular culture and depicted in a vast array of films, artwork, and popular literature. John Milton's closet drama Samson Agonistes is an allegory for the downfall of the Puritans and the restoration of the English monarchy[63] in which the blinded and imprisoned Samson represents Milton himself,[63] the "Chosen People" represent the Puritans,[63] and the Philistines represent the English Royalists.[63] The play combines elements of ancient Greek tragedy and biblical narrative.[64] Samson is portrayed as a hero,[65] whose violent actions are mitigated by the righteous cause in whose name they are enacted.[65] The play casts Delilah as an unrepentant, but sympathetic, deceiver[66] and speaks approvingly of the subjugation of women.[66]

In 1735, George Frideric Handel wrote the opera Samson,[67] with a libretto by Newburgh Hamilton, based on Samson Agonistes.[67] The opera is almost entirely set inside Samson's prison[67] and Delilah only briefly appears in Act II.[67] In 1877, Camille Saint-Saëns composed the opera Samson and Delilah with a libretto by Ferdinand Lemaire in which the entire story of Samson and Delilah is retold.[67] In the libretto, Delilah is portrayed as a seductive femme fatale,[67] but the music played during her parts invokes sympathy for her.[67]

The 1949 biblical drama Samson and Delilah, directed by Cecil B. DeMille and starring Victor Mature and Hedy Lamarr in the titular roles, was widely praised by critics for its cinematography, lead performances, costumes, sets, and innovative special effects.[68] It became the highest-grossing film of 1950,[69] and was nominated for five Academy Awards, winning two.[70] According to Variety, the film portrays Samson as a stereotypical "handsome but dumb hulk of muscle".[71]

Samson has been especially honored in Russian artwork[72] because the Russians defeated the Swedes in the Battle of Poltava on the feast day of St. Sampson, whose name is homophonous with Samson's.[72] The lion slain by Samson was interpreted to represent Sweden, as a result of the lion's placement on the Swedish coat of arms.[72] In 1735, C. B. Rastrelli's bronze statue of Samson slaying the lion was placed in the center of the great cascade of the fountain at Peterhof Palace in Saint Petersburg.[72]

Samson is the emblem of Lungau, Salzburg[73] and parades in his honor are held annually in ten villages of the Lungau and two villages in the north-west Styria (Austria).[73] During the parade, a young bachelor from the community carries a massive figure made of wood or aluminum said to represent Samson.[73] The tradition, which was first documented in 1635,[73] was entered into the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Austria in 2010.[73][74] Samson is one of the giant figures at the "Ducasse" festivities, which take place at Ath, Belgium.[75]

See also

- Gilgamesh

- Samson Option

- Samson Unit

- Shamash

- Strength (Tarot card)

Notes

- Greek: Σαμψών

References

- Van der Toorn, Karel; Pecking, Tom; van der Horst, Peter Willem (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Grand Rapids, MC: William B. Eerdmans. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-80282491-2.

- Margalith, Othniel (January 1987). "The Legends of Samson/Heracles". Vetus Testamentum. 37 (1–4): 63–70. doi:10.1163/156853387X00077.

- Comay, Joan; Brownrigg, Ronald (1993). Who's Who in the Bible: The Old Testament and the Apocrypha, The New Testament. New York: Wing Books. pp. Old Testament, 316–317. ISBN 0-517-32170-X.

- Judges 16:17

- Judges 13

- Judges 13:2

- Rogerson, John W. (1999). Chronicle of the Old Testament Kings: the Reign-By-Reign Record of the Rulers of Ancient Israel. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 58. ISBN 0-500-05095-3.

-

- Comay, Joan; Brownrigg, Ronald (1993). Who's Who in the Bible: The Old Testament and the Apocrypha, The New Testament. New York: Wing Books. pp. Old Testament, 317. ISBN 0-517-32170-X.

- Judges 13:18

- Judges 14

- Judges 14:6, Bible hub.

- Rogerson, John W. (1999). Chronicle of the Old Testament Kings: the Reign-By-Reign Record of the Rulers of Ancient Israel. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 59. ISBN 0-500-05095-3.

- Judges 14:14

- Judges 14:18

- Comay, Joan; Brownrigg, Ronald (1993). Who's Who in the Bible: The Old Testament and the Apocrypha, The New Testament. New York: Wing Books. pp. Old Testament, 318. ISBN 0-517-32170-X.

- Judges 15

- Rogerson, John W. (1999). Chronicle of the Old Testament Kings: The Reign-By-Reign Record of the Rulers of Ancient Israel. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 61. ISBN 0-500-05095-3.

- Judges 16

- Porter, J. R. (2000). The Illustrated Guide to the Bible. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 75. ISBN 0-7607-2278-1.

- Judges 16

- Rogerson, John W. (1999). Chronicle of the Old Testament Kings: The Reign-By-Reign Record of the Rulers of Ancient Israel. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 62. ISBN 0-500-05095-3.

- Judges 16:17

- Judges 16:16 (ESV)

- Comay, Joan; Brownrigg, Ronald (1993). Who's Who in the Bible: The Old Testament and the Apocrypha, The New Testament. New York: Wing Books. pp. Old Testament, 319. ISBN 0-517-32170-X.

- Judges 16:27

- Judges 16:22

- Judges 16:28–30, JPS (1917)

- Levinger, I. M.; Neuman, Kalman (2008). IsraGuide 2007/2008 (pb). Feldheim Publishers. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-59826-154-7.

- BibleGateway – Quick search: Bedan

- Mobley, Gregory (2006). Samson and the Liminal Hero in the Ancient Near East. New York City, New York and London, England: T & T Clark. pp. 5–12. ISBN 978-0-567-02842-6.

- Midrash Genesis Rabbah xcviii. 18

- Ben Yehoyada and Maharal, in commentary to Talmud, tractate "sotah" 10a

- Talmud tractate Sotah 10a.

- Midrash Leviticus Rabbah viii. 2

- Sotah 9b.

- Midrash Eccl. Rabbah i., end

- Leviticus Rabbah. xxiii. 9

- Sotah l.c.

- (Midrash Numbers Rabbah ix. 25)

- (Midrash Genesis Rabbah l.c. § 19)

- Hebrews 11:32-11:34

- Newsome, Carol Ann; Ringe, Sharon H.; Lapsley, Jacqueline E., eds. (2012) [1992]. Women's Bible Commentary (3rd ed.). Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-664-23707-3.

- Thomson, Edward (1838). Prophecy, Types, And Miracles, The Great Bulwarks of Christianity: Or A Critical Examination And Demonstration of Some of The Evidences By Which The Christian Faith Is Supported. Hatchard & Son. p. 299–300. ISBN 9780244031282. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- Heaster, Duncan (2017). Micah: Old Testament New European Christadelphian Commentary. ISBN 9780244031282. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- Beasley, Robert C. (2008). 101 Portraits of Jesus in the Hebrew Scriptures. Signalman. ISBN 9780244031282. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- Lynn G, S (2008). A Study of the Good the Bad and the Desperate Women in the Bible. p. 46. ISBN 9781606473917. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham (1858). "A Guide to Scripture History. The Old Testament". Trinity Hall, Cambridge. p. 190. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- Leviton, Richard (2014). The Mertowney Mountain Interviews. iUniverse. p. 244. ISBN 9781491741290.

- Jastrow, Morris (1898). The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria. Boston: Ginn & Company.

- Charles Fox Burney, The Book of Judges, with Introduction and Notes (London: Rivingtons, 1918).

- Graves, Robert (1955) The Greek Myths cf Herakles.

- Freedman, David Noel, ed. (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of The Bible. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 336 (entry for 'Delilah'). ISBN 0-8028-2400-5.

- Wajdenbaum, P. (2014). Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. pp. 223–227. ISBN 978-1-84553-924-5.

- Cooke, George Albert (1913). The Book of Judges. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Comay, Joan; Brownrigg, Ronald (1993). Who's Who in the Bible: The Old Testament and the Apocrypha, The New Testament. New York: Wing Books. pp. Old Testament, 320. ISBN 0-517-32170-X.

- West, James King (1971). Introduction to the Old Testament. New York City, New York: MacMillan Company. p. 183.

- Gilad, Elon (June 4, 2014). "Intermarriage and the Jews: What Would the Early Israelites Say?". Haaretz. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- Wicker, Brian (2003). "Samson Terroristes: A Theological Reflection on Suicidal Terrorism". New Blackfriars. 84 (983): 42–60. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2005.2003.tb06486.x. ISSN 0028-4289. JSTOR 43250680.

- Atiya, A. S. (1973). "Review of Christian Egypt: Faith and Life". Middle East Journal. 27 (2): 231–232. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4325068.

- Drury, Shadia (2003). "Terrorism: From Samson to Atta". Arab Studies Quarterly. 25 (1/2): 1–12. ISSN 0271-3519. JSTOR 41858434.

- Hasson, Nir (Jul 30, 2012). "National Seal found by Israeli archeologists may give substance to Samson legend". Haaretz. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Smith, Preserved (1930). A History of Modern Culture. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 387. ISBN 978-1-108-07464-3.

- Teskey, Gordon (2006). Delirious Milton: The Fate of the Poet in Modernity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780674010697.

- Lieb, Michael (1994). Milton and the Culture of Violence. London, England: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801429033.

- Guillory, John (1986). "Dalila's House: Samson Agonistes' and the Sexual Division of Labor". In Ferguson, Margaret; Quilligan, Maurren; Vickers, Nancy (eds.). Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226243146.

- Leneman, Helen (2000). "Portrayals of Power in the Stories of Delilah and Bathsheba: Seduction in Song". In Aichele, George (ed.). Culture, Entertainment, and the Bible. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, Ltd. p. 153. ISBN 1-84127-075-X.

- McKay, James (2013). The Films of Victor Mature. McFarland & Company. p. 76. ISBN 9780786449705.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barton, Ruth (2010). Hedy Lamarr: The Most Beautiful Woman in Film. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 174. ISBN 9780813126104.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "23rd Academy Awards Winners". www.oscars.org.

- Variety staff (31 December 1949). "Variety – Review: Samson and Delilah". Variety.

- Wortman, Richard S. (2006). Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy: From Peter the Great to the Abdication of Nicholas II. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-691-12374-5.

- "Samson:Emblem of Lungau". lungau.at. Saliburger Lungau.

- Samsontragen im Lungau und Bezirk Murau Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine, Nationalagentur für das Immaterielle Kulturerbe, Österreichische UNESCO-Kommission

- see fr:Samson (Géant processionnel)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samson. |

- Catalogue entry for Samson (1887) by Solomon Solomon, National Museums Liverpool

Samson Tribe of Dan | ||

| Preceded by Abdon |

Judge of Israel | Succeeded by Eli |