Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport

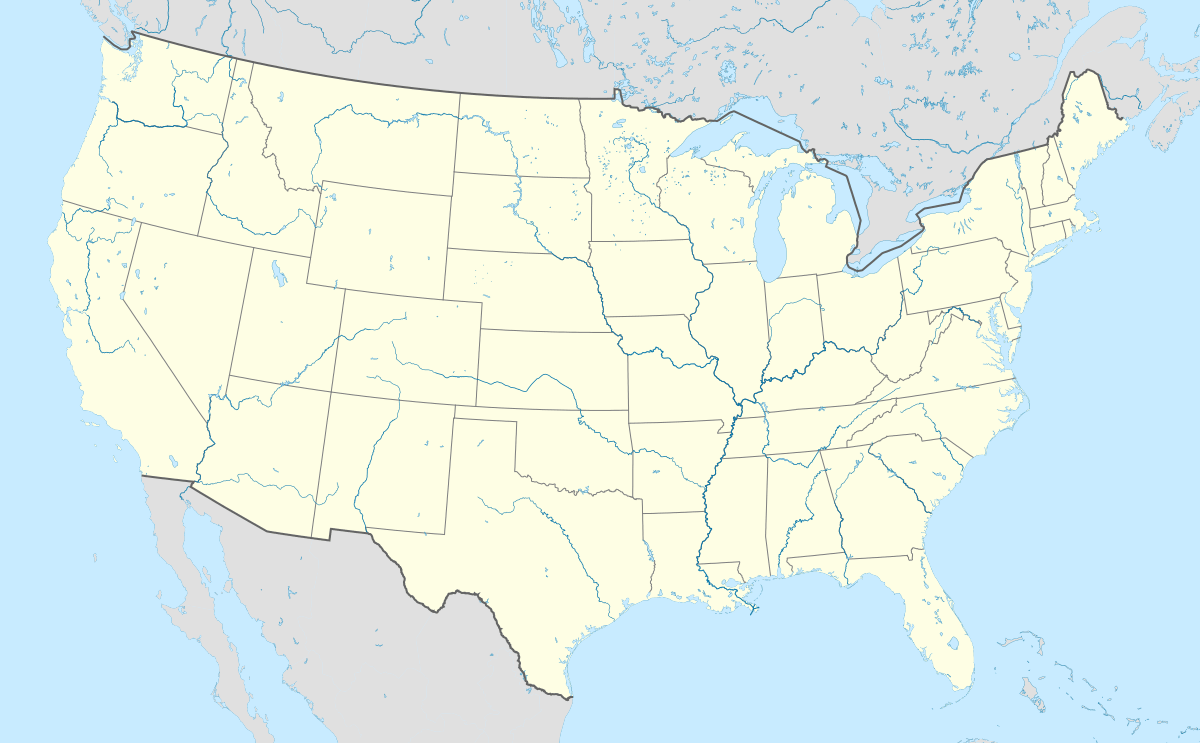

Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (IATA: DCA, ICAO: KDCA, FAA LID: DCA), also known as Reagan National Airport, or, more simply, Washington National, Reagan Airport or National Airport, is an airport in Arlington, Virginia, located adjacent to the border of Washington, D.C. It is the smaller of two commercial airports operated by the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority that serve the National Capital Region (NCR) around Washington, D.C. (the larger airport being Washington Dulles International Airport approximately 30 miles (48 km) to the west in Virginia's Fairfax and Loudoun counties).[2][6] The airport is just 5 miles (8.0 km) from downtown Washington, D.C. and the border is visible from the airport, making it the nearest and most convenient commercial airport to the capital.

Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority United States Government | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Washington metropolitan area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

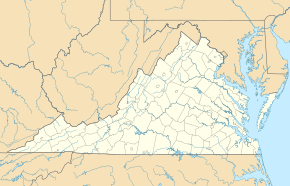

| Location | Arlington, Virginia, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | June 16, 1941[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | American Airlines | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 15 ft / 5 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 38°51′08″N 077°02′16″W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

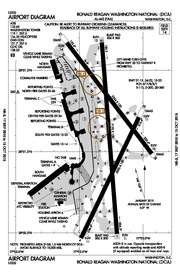

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

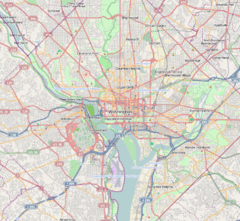

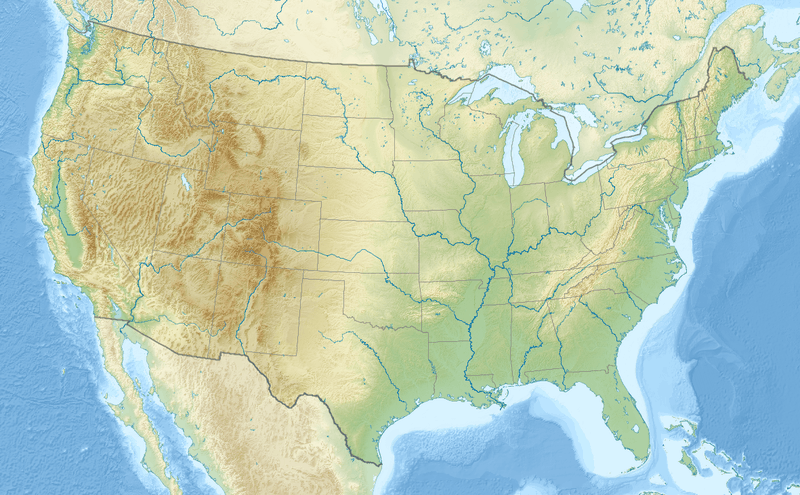

DCA Location in immediate Washington, D.C. area  DCA DCA (Virginia)  DCA DCA (the United States) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2019) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Federal Aviation Administration,[2] Passenger traffic[3]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The airport's original name was Washington National Airport. Congress adopted the present name to honor President Ronald Reagan in 1998.[7][8] MWAA operates the airport with close oversight by the federal government due to its proximity to the national capital.

Flights into and out of the airport are generally not allowed to exceed 1,250 statute miles (2,010 km) in any direction nonstop, in an effort to send coast-to-coast and overseas traffic to the larger but more distant Washington Dulles International Airport, though there are 40 slot exemptions to this rule. Planes are required to take unusually complicated paths to avoid restricted and prohibited airspace above sensitive landmarks, government buildings, and military installations in and around Washington, D.C.,[9] and to comply with some of the tightest noise restrictions in the country.[10]

The small size of this airport imposes serious constraints on its capacity, but Reagan National currently serves 98 nonstop destinations. Reagan is a hub for American Airlines. The airport does not have any United States immigration and customs facilities as the only scheduled international flights allowed to land at the airport are those from airports with U.S. Customs and Border Protection preclearance facilities, which generally encompasses flights from major airports in Canada and from some destinations in the Caribbean. Other international passenger flights to the Washington, D.C. area must use Washington Dulles International Airport or Baltimore–Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport. There are currently five scheduled international routes, which are to cities in Canada, the Bahamas, and Bermuda.[11]

The airport served 23.5 million passengers in 2018.[12] In 2019, DCA served 23,945,527 passengers, an increase of 1.8% over 2018, and a new passenger record for the airport.

History

.jpg)

The first airport in the Washington area with a major terminal was Arlington's Hoover Field, which opened its doors in 1926.[13] Located near the present site of the Pentagon, the facility's single runway was crossed by a street; guards had to stop automobile traffic during takeoffs and landings. The following year Washington Airport, another privately operated field, began service next door.[1] In 1930 the Depression led the two terminals to merge to form Washington-Hoover Airport. Bordered on the east by U.S. Route 1, with its accompanying high-tension electrical wires, and obstructed by a high smokestack on one approach and a dump nearby, the field was inadequate.[14]

Although the need for a better airport was acknowledged in 37 studies conducted between 1926 and 1938,[1] there was a statutory prohibition against federal development of airports. When Congress lifted the prohibition in 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt made a recess appropriation of $15 million to build National Airport by reallocating funds from other purposes. Construction of Washington National Airport began in 1940–41 by a company led by John McShain. Congress challenged the legality of FDR's recess appropriation, but construction of the new airport continued.[15]

The airport is southwest of Washington, D.C. The western part of the airport was once within a large Virginia plantation, a remnant of which is now inside a historic site located near the airport's Metro-rail station (see Abingdon (plantation) for history). The eastern part of the airport was constructed in the District of Columbia on and near mudflats that were within the tidal Potomac River near Gravelly Point, about 4 statute miles (6.4 km) from the United States Capitol, using landfill dredged from the Potomac River.

The airport opened June 16, 1941, just before US entry into World War II.[1] The public was entertained by displays of wartime equipment including a captured Japanese Zero war prize flown in with U.S. Navy colors.[16] In 1945 Congress passed a law that established the airport was legally within Virginia (mainly for liquor sales taxation purposes) but under the jurisdiction of the federal government.[1] On July 1 of that year, the airport's weather station became the official point for D.C. weather observations and records by the National Weather Service, which is located in Washington, D.C.[17]

The April 1957 Official Airline Guide shows 316 weekday departures: 95 Eastern (plus six per week to/from South America), 77 American, 61 Capital, 23 National, 17 TWA, 10 United, 10 Delta, 6 Allegheny, 6 Braniff, 5 Piedmont, 3 Northeast and 3 Northwest. Jet flights began in April 1966 (727-200s were not allowed until 1970).[18] By 1974, the airport's key carriers were Eastern (20 destinations), United (14 destinations after subsuming Capital) and Allegheny (11 destinations).[19]

The grooving of runway 18–36 to improve traction when wet, in March 1967, was a first for a civil airport in the United States.[20]

Service to the airport's Metro station began in 1977.[21]

The Washington National Airport Terminal and South Hangar Line were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997.[4][22]

Expansion and restrictions

The runway layout has changed little since the 1956 closure of a fourth runway, which was on an East-West axis.

- The construction of a North Terminal supplemented the original terminal building in 1958 and continued construction connected the two terminals in 1961.

- A United Airlines holdroom complex was built in 1965, and a facility for American Airlines was completed in 1968. A commuter terminal was constructed in 1970.[1]

- A major terminal expansion, officially called Terminals B/C, and the Metro Station opened in 1997, bringing a significant increase in the number of gates available for commercial flights.

- Runways 18/36 and 3/21 were renumbered as 1/19 and 4/22, respectively, in 1999 due to a shift in the earth's magnetic field.[23]

- In March 2012 the main 1/19 runway was lengthened 300 feet (91 m) to add FAA compliant runway safety runoff areas.[24]

Despite the expansions, efforts have been made to restrict the growth of the airport. The advent of jet aircraft as well as traffic growth led Congress to pass the Washington Airport Act of 1950, which resulted in the opening of Washington Dulles International Airport in 1962. To reduce congestion and drive traffic to alternative airports, the FAA imposed landing slot and perimeter restrictions on National and four other high-density airports in 1969.[25]

The airport originally had no perimeter rule. From 1954 to 1960, airlines operated nonstop flights to California on piston-engine airliners.[26][27] Scheduled jet airliners were not allowed until April 1966, and concerns about aviation noise led to noise restrictions even before jet service began in 1966.

The perimeter rule was implemented in January 1966 as a voluntary agreement by air carriers in order to get permission to use short-haul jets at National. The purpose was to assure that Dulles continued to serve the long haul domestic and international markets, and to limit traffic and noise at National. The FAA assumed that ground level noise would be reduced because planes would take off light on fuel and therefore be up and away quickly. The agreement limited flights to those that were no longer than 650 nautical miles (1,200 km; 750 mi) with 7 grandfathered exceptions. The spirit of the voluntary agreement was regularly violated as flights left National to an airport within the perimeter and then immediately took off again for a destination beyond it. Within a year there was a proposal to reduce the perimeter to 500 nautical miles (930 km; 580 mi), but it was widely opposed and never implemented. Overcrowding at National was later managed by the 1969 High Density Rule, thereby removing one of the justifications for the perimeter agreement.[28]

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, several attempts were made to codify the perimeter rule, but it was not until Dulles was endangered that it actually become a strict rule. In 1970, the FAA lifted the ban at National on the stretch version of the Boeing 727, which resulted in a lawsuit by Virginians for Dulles who argued that the airport's jet traffic was a nuisance. That suit resulted in a Court of Appeals order to create an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). In addition to the court order, there were economic problems at Dulles. Following the extension of Metrorail to National in 1977, and airline deregulation in 1978, traffic at Dulles began to plummet while it increased at National. As part of a slate of efforts to protect Dulles, including removing landing fees and mobile lounge user charges, the FAA proposed regulations as part of the EIS to limit traffic at National and maintain Dulles' role as the area's airport serving long-haul destinations. In 1980, the FAA proposed codifying the perimeter rule as part of a larger rulemaking effort. When the rule was announced, airlines reacted by challenging it in court and, in some cases, scheduling flights beyond the perimeter, to Dallas and Houston, thereby breaking the voluntary agreement. To prevent this, the Metropolitan Washington Airports Policy of 1981 codified the perimeter rule on an interim basis "to maintain the long-haul nonstop service at Dulles and BWI which otherwise would preempt shorter haul service at National." At the same time, the perimeter was extended to 1,000 nautical miles (1,900 km; 1,200 mi) to remove the unfairness of having seven grandfathered cities. The perimeter rule was upheld by the Court of Appeals in 1982.[29][28] In 1986, as part of the Metropolitan Washington Airports Act, which handed control of National over to the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, the perimeter was extended to 1,250 statute miles (2,010 km) to enable direct flights to Houston.[28]

Slots at the airport have been traded in several instances. In 2011, US Airways acquired a number of Delta's slots at National in exchange for Delta receiving a number of US Airways slots at LaGuardia Airport in New York. JetBlue paid $40 million to acquire eight slot pairs at auction during the same year.[30] JetBlue and Southwest acquired 12 and 27 US Airways slot pairs, respectively, in 2014 as part of a government-mandated divestiture following the merger of US Airways and American.[31]

Commercial flights normally use Runway 1/19 (7169' x 150' / 2185 m x 46 m) exclusively, as the shorter Runway 15/33 (5204' x 150' / 1586 m x 46 m) and Runway 4/22 (5000' x 150' / 1524 m x 46 m) can accommodate them only under very windy conditions.

Transfer of control and renaming

In 1984, the Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole appointed a commission to study transferring National and Dulles Airports from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to a local entity, which could use airport revenues to finance improvements.[15] The commission recommended that one multi-state agency administer both Dulles and National, over the alternative of having Virginia control Dulles and the District of Columbia control National.[15] In 1987 Congress, through legislation,[32] transferred control of the airport from the FAA to the new Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority with the Authority's decisions being subject to a Congressional review panel. The constitutionality of the review panel was later challenged in the Supreme Court and the Court has twice declared the oversight panel unconstitutional.[33] Even after this decision, however, Congress has continued to intervene in the management of the airports.[34]

On February 6, 1998, President Bill Clinton signed legislation[35] changing the airport's name from Washington National Airport to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, to honor the former president on his 87th birthday.[36] The legislation, passed by Congress in 1998,[37] was drafted against the wishes of MWAA officials and political leaders in Northern Virginia and Washington, D.C.[38][39] Opponents of the renaming argued that a large federal office building had already been named for Reagan (the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center) and that the airport was already named for a United States president (George Washington).[39] The bill expressly stated that it did not require the expenditure of any funds to accomplish the name change; however, state, regional, and federal authorities were later required to change highway and transit signs at their own additional expense as new signs were made.[40][41]

Construction of current terminal buildings

With the addition of more flights and limited space in the aging main terminal, the airport began an extensive renovation and expansion in the 1990s. Hangar 11 on the northern end of the airport was converted into The USAir Interim Terminal, designed by Joseph C. Giuliani, FAIA. Soon after an addition for Delta Air Lines was added in 1989 and was later converted to Authority offices. These projects allowed for the relocation of several gates in the main terminal until the new $450 million terminal complex became operational. On July 27, 1997, the new terminal complex, consisting of terminals B and C and two parking garages, opened. Argentine architect César Pelli designed the new terminals of the airport. The Interim Terminal closed immediately after its opening and was converted back into a hangar. One pier of the main terminal (now widely known as Terminal A), which mainly housed American Airlines and Pan Am, was demolished; the other pier, originally designed by Giuliani Associates Architects for Northwest/TWA remains operational today as gates 1–9.

Operations

Perimeter restrictions

Reagan National Airport is subject to a federally mandated perimeter limitation to keep it a "short-haul" airport and to keep most "long-haul" air traffic to Dulles International Airport.[42] The rule was implemented in 1966 and originally limited nonstop service to 650 statute miles (1,050 km), with some exceptions for previously existing service.[42] Congress extended the limit in the 1980s to 1,000 miles (1,600 km) and then again to 1,250 miles (2,010 km).[43] Congress and the United States Department of Transportation have created many "beyond-perimeter" exceptions that have weakened the rule.[43]

Members of Congress have repeatedly sought to extend the limit and permit exceptions in order to allow nonstop service from Reagan Airport to their home states and districts.[44][45] In 1999, Senator John McCain of Arizona introduced legislation to remove the 1,250 statute miles (2,010 km) restriction.[46] In the end the restriction was not lifted, but in 2000 the FAA was permitted to add 24 exemptions, which went to Alaska Airlines for flights to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. America West later obtained exemptions for non-stop flights to Phoenix in 2004. In May 2012, the DOT granted new exemptions for Alaska to serve Portland, JetBlue to serve San Juan, Southwest to serve Austin, and Virgin America to serve San Francisco. American, Delta, United, and US Airways were also each allowed to exchange a pair of in-perimeter slots for an equal number of beyond-perimeter slots.[47]

Approach patterns

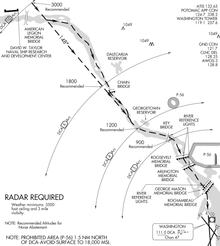

Reagan National Airport has some of the strictest noise restrictions in the country.[10] In addition, due to security concerns, the areas surrounding the National Mall and U.S. Naval Observatory in central Washington are prohibited airspace up to 18,000 feet (5,500 m). Due to these restrictions, pilots approaching from the north are generally required to follow the path of the Potomac River and turn just before landing. This approach is known as the River Visual. Similarly, flights taking off to the north are required to climb quickly and turn left.[49][50]

The "River Visual" is only possible with a ceiling of at least 3,500 feet (1,100 m) and visibility of 3 statute miles (4.8 km) or more.[51] There are lights on the Key Bridge, Theodore Roosevelt Bridge, Arlington Memorial Bridge, and the George Mason Memorial Bridge to aid pilots following the river. Aircraft using the approach can be observed from various parks on the river's west bank. Passengers on the left side of an airplane can see the Capitol, the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, the Jefferson Memorial, the World War II Memorial, Georgetown University, the National Mall, portions of downtown (including the roof of Capital One Arena), and the White House. Passengers on the right side can see CIA headquarters, Arlington National Cemetery, the Pentagon, eastern Arlington (including portions of Rosslyn, Clarendon, Ballston, and Crystal City), and the United States Air Force Memorial.

When the River Visual is not available due to visibility or winds, aircraft may fly an offset localizer or GPS approach to Runway 19 along a similar course (flying a direct approach course on instruments as far as Rosslyn, and then turning to align with the runway visually moments before touchdown). Most airliners are also capable of performing a VOR or GPS approach to the shorter Runway 15/33. Northbound visual and ILS approaches to Runway 1 are also sometimes used; these approaches follow the Potomac River from the south and overfly the Woodrow Wilson Bridge.[52]

Special security measures

Reagan National Airport is in between two overlapping No Fly Zones so pilots have to watch out for the Pentagon and CIA headquarters. On takeoff, pilots must ascend quickly and sharply turn left so they don't fly over the White House. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, security forces strongly enforce these rules. Reagan National has extra security precautions required by the Washington Air Defense Identification Zone that have been in place since the airport began operations.[49]

After the September 11 attacks, the airport was closed for several weeks, and security was tightened when it reopened. Increased security measures included:

- A ban on aircraft with more than 156 seats (lifted in April 2002)[53]

- A ban on the "River Visual" approach (lifted in April 2002)[53]

- A requirement that, 30 minutes prior to landing or following takeoff, passengers were required to remain seated; if anyone stood up, the aircraft was to be diverted to Washington Dulles International Airport under military escort and the person standing would be detained and questioned by federal law enforcement officials (lifted in July 2005)[54]

- A ban on general aviation (lifted in October 2005, subject to the restrictions below)[55]

On October 18, 2005, Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport was reopened to general aviation on a limited basis (48 operations per day) and under restrictions: passenger and crew manifests must be submitted to the Transportation Security Administration 24 hours in advance, and all planes must pass through one of 27 "gateway airports" where re-inspections of aircraft, passengers, and baggage take place. An armed security officer must be on board before departing a gateway airport.[56] On March 23, 2011, the air traffic control supervisor on duty reportedly fell asleep during the night shift. Two aircraft on approach to the airport were unable to contact anyone in the control tower and landed unassisted.[57]

Terminals and facilities

DCA has 46 gates with jetways: 9 gates in Terminal A, 12 in Terminal B and 25 in Terminal C.[58]

Terminal A

Designed by architect Charles M. Goodman, terminal A opened in 1941 and was expanded in 1955 to accommodate more passengers and airlines. The exterior of this terminal has had its original architecture restored, with the airside façade restored in 2004 and the landside façade restored in 2008.[59] The terminal underwent a $37 million renovation that modernized the airport's look by bringing in brighter lighting, more windows, and new flooring. The project was completed in 2014 along with a new expanded TSA security checkpoint.[60] In 2014, additional renovations were announced including new upgraded concessions and further structural improvements, the project was completed in 2015.[61] Terminal A contains gates 1–9 and houses operations from Air Canada Express, Frontier, and Southwest.

Terminals B and C

Terminals B and C are the airport's newest and largest terminals; the terminals opened in 1997 and replaced a collection of airline-specific terminals built during the 1960s. The new terminals were designed by architect Cesar Pelli and house 35 gates. Both terminals share the same structure and are directly connected to the WMATA airport station via indoor pedestrian bridges.

Terminals B and C have three concourses. Terminal B (gates 10–22) houses Alaska Airlines, Delta, and United. Terminal B/C (gates 23–34) houses American and JetBlue. Terminal C (gates 35–45) is exclusive to American.[62] The corridor/hall connecting the three concourses of Terminal B and C is known as National Hall. Terminal B houses a Delta Sky Club and United Club, and there are American Admirals Clubs in both Terminal B/C and Terminal C.[63]

Terminal D

MWAA has begun construction of a new concourse north of Terminal C to accommodate 14 new regional jet gates with jetways. This will replace "Gate 35X," a bus gate currently used to bring passengers to and from American Eagle flights that use parking spots on the ramp. In addition, the individual security checkpoints for the three concourses in Terminals B and C will be replaced with higher-capacity security checkpoints in a new building to the west of National Hall and above the existing arrivals roadway, placing all of National Hall within the secured area of the airport and allowing passengers to walk between concourses without re-clearing security. Construction commenced in February 2018 and is projected for completion by 2021.[64]

Ground transportation

The Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport station on the Washington Metro, serving the Yellow and Blue lines, is located on an elevated outdoor platform station adjacent to Terminals B and C. Two elevated pedestrian walkways connect the station directly to the concourse levels of Terminals B and C. An underground pedestrian walkway and shuttle services provide access to Terminal A.

Metrobus provides service on weekend mornings before the Metro station opens or during any disruptions to regular Metro service.

Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport is located on the George Washington Memorial Parkway, and connected to U.S. Route 1 by the Airport Viaduct (State Route 233). Interstate 395 is just north of the airport, and is also accessible by the G.W. Parkway and U.S. Route 1.[65] Airport-operated parking garage facilities as well as economy lots are available adjacent to or near the various airport terminals.

The airport is accessible by bicycle and foot from the Mt. Vernon Trail, as well as the sidewalk along the Airport Viaduct (State Route 233), which connects the airport grounds to U.S. Route 1. A total of 48 bike parking spots are available across six separate bike racks. The Airport will have a Capital Bikeshare station.[66]

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

| Airlines | Destinations | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Air Canada Express | Montréal–Trudeau, Ottawa, Toronto–Pearson | [67] |

| Alaska Airlines | Los Angeles, Portland (OR), San Francisco, Seattle/Tacoma | [68] |

| American Airlines | Atlanta, Boston, Charlotte, Chicago–O'Hare, Dallas/Fort Worth, Fort Myers, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Memphis, Miami, New York–LaGuardia, Orlando, Philadelphia, Phoenix–Sky Harbor, Tampa Seasonal: Bermuda, Pittsburgh, Raleigh/Durham, West Palm Beach | [69] |

| American Eagle | Akron/Canton, Albany, Asheville (begins May 9, 2020),[70] Atlanta, Augusta (GA), Bangor, Birmingham (AL), Buffalo, Burlington (VT), Charleston (SC), Charleston (WV), Charlotte, Chattanooga, Chicago–O'Hare, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbia (SC), Columbus–Glenn, Dayton, Des Moines, Detroit, Fayetteville/Bentonville, Grand Rapids, Greensboro, Greenville/Spartanburg, Hartford, Huntsville, Indianapolis, Jackson (MS), Jacksonville (FL), Kansas City, Key West, Knoxville, Lansing, Little Rock, Louisville, Manchester (NH), Memphis, Minneapolis/St. Paul, Montgomery, Myrtle Beach, Nashville, New Orleans, New York–JFK, Norfolk, Oklahoma City, Panama City (FL),[71] Pensacola, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Portland (ME), Providence, Raleigh/Durham, Rochester (NY), Sarasota, Savannah, St. Louis, Syracuse, Tallahassee, Toronto–Pearson, West Palm Beach, White Plains, Wilmington (NC) Seasonal: Destin/Fort Walton Beach, Hilton Head, Martha's Vineyard, Melbourne (FL), Nantucket, Nassau, Traverse City (begins June 20, 2020)[72] | [69] |

| Delta Air Lines | Atlanta, Detroit, Los Angeles, Minneapolis/St. Paul, New York–JFK, Salt Lake City | [73] |

| Delta Connection | Boston, Cincinnati, Lexington, Madison, New York–JFK, New York–LaGuardia, Omaha, Raleigh/Durham | [73] |

| Frontier Airlines | Denver | [74] |

| JetBlue | Boston, Fort Lauderdale, Fort Myers, Nassau, Orlando, San Juan, West Palm Beach Seasonal: Martha's Vineyard (begins June 12, 2020),[75] Nantucket | [76] |

| Southwest Airlines | Atlanta, Austin, Chicago–Midway, Columbus–Glenn, Dallas–Love, Fort Lauderdale, Houston–Hobby, Kansas City, Milwaukee, Nashville, New Orleans, Oklahoma City, Omaha, Orlando, Providence, St. Louis, Tampa Seasonal: Fort Myers | [77] |

| United Airlines | Chicago–O'Hare, Denver, Houston–Intercontinental, San Francisco | [78] |

| United Express | Chicago–O'Hare, Houston–Intercontinental, Newark | [78] |

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 855,000 | American, Delta, Southwest | |

| 2 | 779,000 | American, United | |

| 3 | 771,000 | American, Delta, JetBlue | |

| 4 | 452,000 | American, Delta, JetBlue, Southwest | |

| 5 | 452,000 | American | |

| 6 | 452,000 | American | |

| 7 | 356,000 | American | |

| 8 | 305,000 | American, Delta | |

| 9 | 303,000 | American, Delta | |

| 10 | 296,000 | American, Delta | |

Airline market share

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Market Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | American Airlines | 5,595,000 | 24.87% |

| 2 | Southwest Airlines | 3,473,000 | 15.44% |

| 3 | Delta Air Lines | 2,552,000 | 11.35% |

| 4 | JetBlue Airways | 1,789,000 | 7.95% |

| 5 | United Airlines | 1,134,000 | 5.04% |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 18,118,713 | 2000 | 15,888,199 | ||

| 2019 | 23,945,527 | 2009 | 17,577,359 | 1999 | 15,185,348 |

| 2018 | 23,464,618 | 2008 | 18,028,287 | 1998 | 15,970,306 |

| 2017 | 23,903,248 | 2007 | 18,679,343 | 1997 | 15,907,006 |

| 2016 | 23,595,006 | 2006 | 18,550,785 | 1996 | 15,226,500 |

| 2015 | 23,039,429 | 2005 | 17,847,884 | 1995 | 15,506,244 |

| 2014 | 20,810,387 | 2004 | 15,944,542 | 1994 | 15,700,825 |

| 2013 | 20,415,085 | 2003 | 14,223,123 | 1993 | 16,307,808 |

| 2012 | 19,655,440 | 2002 | 12,881,601 | 1992 | 15,593,535 |

| 2011 | 18,823,094 | 2001 | 13,265,387 | 1991 | 15,098,697 |

Abingdon plantation historical site

A part of the airport is located on the former site of the 18th and 19th century Abingdon plantation, which was associated with the prominent Alexander, Custis, Stuart, and Hunter families.[82] In 1998, MWAA opened a historical display around the restored remnants of two Abingdon buildings and placed artifacts collected from the site in an exhibit hall in Terminal A.[83][84] The Abingdon site is located on a knoll between parking Garage A and Garage B/C, near the south end of the Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport Metrorail station.[83][85][86][87]

Accidents and incidents

Page Airways

On April 27, 1945 a Page Airways Lockheed Model 18 Lodestar, (Flight # unknown), bound for New York, (airport unknown) crashed into a deep ditch at the end of runway 33 after aborting a takeoff due to engine failure. There were strong gusts and ground turbulence at the time. Out of the 13 passengers and crew on board, 6 passengers were killed.[88]

Eastern Air Lines Flight 537

On November 1, 1949, a mid-air collision between an Eastern Air Lines passenger aircraft and a P-38 Lightning military plane took the lives of 55 passengers. The sole survivor was the Bolivian ace pilot of the fighter plane, Erick Rios Bridoux.[89]

Bridoux's plane had taken off from National just 10 minutes earlier and was in contact with the tower during a brief test flight. The Eastern Air Lines DC-4 was on approach from the south when the nimble and much faster P-38 banked and plunged right into the passenger plane. Both aircraft dropped into the Potomac River.

Capital Airlines Flight 500

On December 12, 1949, Capital Airlines Flight 500, a Douglas DC-3, stalled and crashed into the Potomac River while on approach to Reagan National. Six of the 23 passengers and crew on board were killed.[90]

Air Florida Flight 90

On the afternoon of January 13, 1982,[91] following a period of exceptionally cold weather and a morning of blizzard conditions, Air Florida Flight 90 crashed after waiting forty-nine minutes on a taxiway and taking off with ice and snow on the wings. The Boeing 737 aircraft failed to gain altitude. Less than 1 statute mile (1.6 km) from the end of the runway, the airplane struck the 14th Street Bridge complex, shearing the tops off vehicles stuck in traffic before plunging through the 1-inch-thick (25 mm) ice covering the Potomac River. Rescue responses were greatly hampered by the weather and traffic. Due to action on the part of motorists, a United States Park Service police helicopter crew, and one of the plane's passengers who later perished, five occupants of the downed plane survived. The other 74 people who were aboard died, as well as four occupants of vehicles on the bridge. President Reagan cited motorist Lenny Skutnik in his State of the Union Address a few weeks later.

References

- "History". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. 2011. Archived from the original on January 5, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- FAA Airport Master Record for DCA (Form 5010 PDF)

- "Reagan Air Traffic Statistics". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. January 2019. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- "Airport Data and Information Portal". adip.faa.gov. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- Kellman, Laurie (February 5, 1998). "Clinton to sign bill renaming National Airport for Reagan". The Day. New London, Connecticut. Associated Press. p. A3. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- "What's in an eponym? Celebrity airports – could there be a commercial benefit in naming?". Centre for Aviation. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- Anatomy: Landing a Plane at Reagan National Airport

- "Aircraft Noise Procedures and Guidelines at Reagan National Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- Map of 98 Nonstop Destinations at Reagan National

- Dulles International and Reagan National Airports Passenger Traffic Tops 47.5 Million in 2018

- "Arlington's Flying Field is Dedicated". The Washington Post. July 17, 1926. p. 20. ProQuest 149713699.

- "McCarran Sees Death Peril in Local Airport: Says Major Disaster Has Been Prevented Here Only by Luck". The Washington Post. May 13, 1938.

- Feaver, Douglas B. (July 16, 1997). "Years of Deal-Making Enabled Change From 'Disgrace' to Showplace". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- Nicholas, William H. & Edwards, Walter Meayers (September 1943). "Wartime Washington". National Geographic.

- Threaded Extremes

- Aviation Daily February 26, 1971 p314

- "DCA74intro". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- McGuire, R.C. (January 1, 1969). "REPORT ON GROOVED RUNWAY EXPERIENCE AT WASHINGTON NATIONAL AIRPORT". Internet Archive. Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- "History of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. 2011. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- Carol Hooper; Elizabeth Lampl & Judith Robinson (April 1994). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Washington National Airport Terminal and South Hangar Line" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2013. and Accompanying photo Archived October 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.ncei.noaagov/news/airport-runway-names-shift-magnetic-field |November 20, 2017; retrieved on July 6, 2018

- Runway Projects Archived July 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Metwashairports.com. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- "Code of Federal Regulations, Volume 2, Part 93, Subpart K" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. October 24, 1970. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- "American Airlines timetable, 1958". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- "TWA timetable, 1959". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- Knickerbocker, Dr. Nancy Norgaard. "The History of National Airport". Citizens for the Abatement of Aircraft Noise. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- "Metropolitan Washington Airports" (PDF). Federal Register. 46 (228): 58036–58037. November 27, 1981. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- "US Airways' Washington Airport Prize Hobbles AMR Merger". www.bloomberg.com. August 29, 2013. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "JetBlue, Southwest gain slots at Reagan Airport". USA TODAY. January 30, 2014. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Metropolitan Washington Airports Act of 1986", Public Law No. 99-500, Section 6001

- METROPOLITAN WASHINGTON AIRPORTS AUTHORITY v. CITIZENS FOR THE ABATEMENT OF AIRCRAFT NOISE, INC., 501 U.S. 252 (1991).

- This can be seen by Congress's continued use of legislation to limit the number of flights at National Airport, as well as expanding the perimeter and number of exemptions for flights outside that limit.

- "Public Law No. 105-154, "To rename the Washington National Airport located in the District of Columbia and Virginia as the 'Ronald Reagan National Airport'"". January 27, 1998.

- "It's Reagan Airport now". McCook Daily Gazette. Associated Press. February 7, 1998. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- "Bill renames Washington National Airport after Reagan". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. January 28, 1988. p. A3. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- Alvarez, Lizette (February 4, 1998). "G.O.P. Tries to Wrap Up an Airport for Reagan". The New York Times.

- "Congress Votes for Reagan Airport". Washington Post. February 5, 1998. p. A01. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- "Hansen in road sign rage over lack of Reagan airport markers". Deseret News. June 7, 1998.

- Zachary M. Schrag (2006). The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. JHU Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780801889066.

- DCA Reagan National - Slot & Perimeter Rules

- Proposal to extend DCA's 'perimeter rule' withdrawn

- 3 SENATORS GAIN FROM AIRPORT BILL

- House member withdraws plan to expand flights at National airport

- Sipress, Alan (November 11, 1999). "More Flights Unlikely Now At National". The Washington Post. p. B1. ProQuest 408563593.

- DOT Selects Four Cities to Receive New Nonstop Service to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport | Department of Transportation Archived February 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Dot.gov (May 14, 2012). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- "Why you should NEVER fly into Washington National Airport". JetHead's Blog. December 24, 2011. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- "Security-Restricted Airspace". Federal Aviation Administration. December 13, 2005. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- "eCFR-Code of Federal Regulations". U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- Garrison, Kevin (1993). Congested Airspace: A Pilot's Guide (Command Decisions Ser.). Riverside, Conn: Belvoir Publications. p. 157. ISBN 1-879620-13-8. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- "AirNav: KDCA – Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport". www.airnav.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- "Secretary Mineta Announces Beginning of Security Screening Program; BWI First to Deploy Federal Screening Personnel". Transportation Security Administration. April 24, 2002. Archived from the original on May 22, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- "TSA Suspends 30-Minute Rule for Reagan National Airport". Transportation Security Administration. July 14, 2005. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- "TSA Opens Ronald Reagan Washington Airport to General Aviation Operations". Transportation Security Administration. October 18, 2005. Archived from the original on May 22, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- "Restoration of General Aviation at Washington Reagan National Airport". Transportation Security Administration. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ""Uncontrolled airport" situation at Washington National". eTurboNews. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- https://travelwidget.com/Ronald-Reagan-Washington-National-DCA-airport-terminal-map

- "History of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Aratani, Lori (August 27, 2013). "Reagan National's Terminal A is Getting $37M Facelift". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- MWAA Terminal A Renovation "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "DCA Terminal Map" (PDF). flyreagan.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- "Airline Lounges". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- Lazo, Luz (February 17, 2018). "Reagan National's rehab project will create some pain for drivers and travelers". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (2011). "Directions to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport". Reagan National Airport. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- "Washington National Airport Pedestrian/Bike Access" (PDF). Crystal City Business Improvement District. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- "Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on September 25, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Flight Timetable". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Flight schedules and notifications". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Liu, Jim. "American Airlines expands Boston / Asheville service in S20". Routesonline. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://news.aa.com/news/news-details/2019/20-New-Routes-for-Summer-2020/default.aspx

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Frontier". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "JetBlue adds Washington Reagan – Martha's Vineyard service in S20". Routes Online. December 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- "JetBlue Airlines Timetable". Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Check Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Washington, DC: Ronald Reagan Washington National (DCA)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Washington, DC: Ronald Reagan Washington National (DCA)". www.transtats.bts.gov. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "Reagan Air Traffic Statistics". Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- Templeman, Eleanor Lee (1959). Arlington Heritage: Vignettes of a Virginia County. New York: Avenel Books, a division of Crown Publishers, Inc. pp. 12–13. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (November 12, 1998). "Historic Site At Airport Open to Travelers And Public". Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- Sipress, Alan (November 11, 1998). "At National Airport, A Historic Destination". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Post Company. pp. B1, B7. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- "Parking Map". DCA Terminal Map. Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. June 2011. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- Cressey, Pamela J. (2002). Walk and Bike the Alexandria Heritage Trail: A Guide to Exploring a Virginia Town's Hidden Past. Capital Books. pp. 16–17. ISBN 1-892123-89-4. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- Coordinates of Abingdon Plantation historical site: 38°51′4.8″N 77°2′40.2″W

- Accident description for NC33328 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on April 11, 2019.

- "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas C-54". Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- "Accident report for DC-3 NC-25691 on December 12, 1949". Civil Aeronautics Board Accident Report. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- "We're Going Down, Larry". Time. 119 (7): 21. February 15, 1982. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. |

- Official website

- Airport Map Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. June 2011

- KDCA - Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport at airnav.com

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective April 23, 2020

- FAA Terminal Procedures for DCA, effective April 23, 2020

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KDCA

- ASN accident history for DCA

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KDCA

- FAA current DCA delay information