Riverside Church

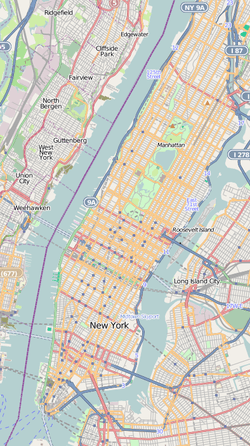

Riverside Church is a Baptist and Congregationalist church in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It is located on the block bounded by Riverside Drive, Claremont Avenue, and 120th and 122nd Streets, near Columbia University's Morningside Heights campus and across from Grant's Tomb. An interdenominational church, it is associated with the American Baptist Churches USA and the United Church of Christ. The church was conceived by philanthropist businessman John D. Rockefeller Jr., a Baptist, in conjunction with Presbyterian minister Harry Emerson Fosdick as a large, interdenominational church in Morningside Heights, a neighborhood surrounded by numerous academic institutions.

| Riverside Church | |

|---|---|

Riverside Church  Riverside Church  Riverside Church  Riverside Church | |

| 40°48′43″N 73°57′47″W | |

| Location | New York City |

| Country | United States |

| Denomination | Interdenominational, American Baptist, United Church of Christ |

| Membership | 1,750[1] |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | Mulberry Street Baptist Church Fifth Avenue Baptist Church Park Avenue Baptist Church |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | National Register of Historic Places, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission |

| Architect(s) | Allen & Collens and Henry C. Pelton |

| Architectural type | Neo-Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | November 21, 1927 |

| Completed | October 5, 1930 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 2,100 |

| Nave width | 89 feet (27 m) |

| Number of floors | 22 |

| Spire height | 392 feet (119 m) |

| Bells | 74 (carillon) |

Riverside Church | |

New York City Landmark No. 2037 | |

| Location | 478, 490 Riverside Dr. & 81 Claremont Ave., New York City |

| Built | 1930 (main building) 1957 (MLK Wing) 1962 (conversion of Stone Gym) |

| Architect | Allen & Collens, H.C. Pelton (main building) Collens, Willis & Beckonert (MLK Wing) Louis E. Jallade (Stone Gym) |

| Architectural style | Late Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 12001036 |

| NYCL No. | 2037 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 12, 2012[2] |

| Designated NYCL | May 16, 2000[3] |

The original building, opened in 1930, was designed by Henry C. Pelton and Allen & Collens in the Neo-Gothic style. It contains a nave consisting of five architectural bays; a chancel at the front of the nave; a 22-story, 392-foot-tall (119 m) tower above the nave; a narthex and chapel; and a cloistered passageway that connects to the eastern entrance on Claremont Avenue. The main feature of the church is the 74-bell carillon near the top of the tower, dedicated to John Rockefeller Jr.'s mother Laura Spelman Rockefeller. A seven-story wing to the south of the original building was built in 1959 to a design by Collens, Willis & Beckonert, and renamed for Martin Luther King Jr. in 1985. The Stone Gym, to the southeast, was built in 1915 as a dormitory designed by Louis E. Jallade, and was converted to a gym in 1962.

A focal point of global and national activism since its inception, Riverside Church has a long history of social justice, in adherence to Fosdick's original vision of an "interdenominational, interracial, and international" church.[3] Riverside Church's congregation includes more than forty ethnic groups. It was designated as a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2000,[3] and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012.[2]

History

Context

Congregation

Several small Baptist congregations were founded in Manhattan after the American Revolutionary War, including the Mulberry Street Baptist Church, established in 1823 by a group of 16 congregants.[4][5] The church occupied at least three locations in the Lower East Side, and two additional locations on Broadway in Midtown Manhattan, before moving to a more permanent site at Fifth Avenue and 46th Street in the 1860s.[4] The businessman William Rockefeller was the first of several Rockefeller family members to attend the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church, and became a major financial backer of the church in the 1870s.[4][6] Such was the family's involvement that William and his brother John D. Rockefeller later became trustees of the church, and many of the church's services were held at the Rockefellers' home nearby.[4][7]

When Cornelius Woelfkin became the church's minister in 1912, he started leading the church toward a more modernist direction.[8] By the early 20th century, Fifth Avenue was seeing growing commercial development, and the church building became dilapidated.[9] The congregation sold off their old headquarters in 1919[10] and bought land at Park Avenue and 63rd Street the following year.[11] John Rockefeller's son John D. Rockefeller Jr. funded half of the projected $1 million cost.[4][12] The new church, dubbed the "Little Cathedral", was designed by Henry C. Pelton in partnership with Francis R. Allen and Charles Collens.[4] The final service in the Fifth Avenue location was held on April 3, 1922,[13] and the renamed Park Avenue Baptist Church held its first class in the new location the next week.[4][14]

Progressive ideology

In 1924, John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated $500,000 to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Morningside Heights, further uptown in Manhattan, in an unsuccessful attempt to influence the cathedral's ideology in a progressive direction.[15] The following January, Harry E. Edmonds—leader of the International House in Morningside Heights, for whose construction Rockefeller had provided funds—wrote to Rockefeller to propose creating a new church in the neighborhood. Edmonds suggested that progressive pastor Harry Emerson Fosdick head such a church. Rockefeller then told the Park Avenue Baptist Church's leaders about the plan, after which he hired an agent to look at the planned church site.[16]

Woelfkin quit in mid-May 1925 and Rockefeller Jr. immediately started looking for a new minister,[17] ultimately deciding on Fosdick.[16][18][19] Fosdick had declined Rockefeller's offers several times,[16] explaining that he did not "want to be known as the pastor of the richest man in the country."[19] Fosdick stated that he would accept the minister position under the conditions that the church move to Morningside Heights, follow a policy of religious liberalism, remove the requirement that members had to be baptized, and have the church be nondenominational.[19][20][21] At the end of May 1925, Fosdick finally agreed to become minister of the Park Avenue Baptist Church.[18][20][22][23] Only 15% of congregants voted against Fosdick's appointment.[24]

Under Fosdick's leadership, the congregation doubled in size by 1930.[18][25] The new members were diverse: of the 158 people who joined in the year after Fosdick became minister, about half were not Baptists.[18][26] Though some existing congregants had doubts about whether the Park Avenue Baptist Church should move from its recently completed edifice, the church's board, which was in favor of the relocation, stated that congregants would not have to pay any of the costs for the new church.[27]

Planning and construction

Site selection

Morningside Heights, where the new church was to be located, was quickly being developed as a residential neighborhood surrounded by numerous higher-education institutions, including Union Theological Seminary and International House of New York.[28][29] The development had been spurred by the presence of Riverside Park and Riverside Drive nearby, as well as the construction of the New York City Subway's Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (the modern-day 1 train) under Broadway.[18][28] Rockefeller briefly considered a location on Morningside Drive, on the eastern edge of Morningside Heights. However, he ultimately decided on a site at the southeast corner of Riverside Drive and 122nd Street on the neighborhood's western border, which overlooked Riverside Park to the west and Claremont Park to the north.[29][30] Rockefeller felt that the Riverside Drive site was more easily visible, since it abutted the Hudson River and would be seen by recreational users of Riverside Drive.[30]

In May 1925, Rockefeller finalized his purchase of the new church's site at Riverside Drive.[31] That July, he exchanged his previous purchase of a plot on Morningside Drive for another plot on Riverside Drive.[32] Shortly afterward, he acquired yet more land, after which he had a frontage of 250 feet (76 m) on Riverside Drive for the new church.[33] At the time of the acquisition, three apartment buildings and two mansions occupied the church's future site. Rockefeller wished to keep the apartments in place for several years to fund the church's eventual construction.[30]

Planning

Rockefeller was the chairman of the committee tasked with creating a new building for the church. Hoping to avoid publicity, he did not host an architectural competition, but instead, privately asked several architectural firms to submit plans for the building.[29][34][lower-alpha 1] Rockefeller tried to downplay his role in the planning and construction process, asking that his name not be mentioned in media reports or discussion of the church, though with little success.[20] His role in the selection process raised concerns from church trustees such as Fosdick, who believed that such close financial involvement could place the church in "a very vulnerable position".[36][29] John Roach Straton, reverend of the Calvary Baptist Church on 57th Street in Midtown Manhattan, criticized Rockefeller's involvement and mockingly suggested that it be called the Socony Church, after the oil company headed by the Rockefellers.[37] George S. Chappell, writing in The New Yorker under the pseudonym "T-Square", joked that the project "was known to most secular minds as the Rockefeller Cathedral."[20][38]

Neither Rockefeller nor Fosdick had strict requirements for the church's architectural style. Rockefeller only asked that the new building include space for the Park Avenue Baptist Church's carillon, which he had donated.[34] Most of the plans entailed a church facing 122nd Street and wrapping around the existing apartment buildings on the site. The exception was a plan by Allen & Collens and Henry C. Pelton, who had designed the Park Avenue Baptist Church. Their plan called for a Gothic Revival church with its main entrance on the side, facing Riverside Drive, with a bell tower as well as apartment towers for the neighboring Union Theological Seminary.[39] The building committee removed the apartment towers from the church plan, and Allen, Collens, and Pelton were selected to design the new church in February 1926.[29][39][40] As part of the plans, there would be a 375-foot-tall (114 m) bell tower (later changed to 392 feet (119 m)), a 2,400-seat auditorium, and athletic rooms. The building would occupy a lot 100 feet (30 m) wide by 225 feet (69 m) long.[29][40] Since there was no room for a chapel in the original plans, Rockefeller proposed trading land with the Union Theological Seminary. In May 1926, Rockefeller gave Union an apartment building on 99 Claremont Avenue, to the northeast of the church. In exchange, Riverside Church received a small plot to its south, allowing for the construction of the chapel as well as a proposed cloister passage to Claremont Avenue.[41]

Rockefeller chose to delay the construction process until after the leases of the site's existing tenants expired in October.[40] The official plans were filed with the New York City Department of Buildings in November 1926.[42] The congregation voted to approve the building plans that December, at a cost of $4 million.[43] Pelton and Collens then went to France, driving over 2,500 miles (4,000 km) within the country to look for churches upon which to model Riverside Church's design.[44][45] They eventually selected the 13th-century Chartres Cathedral as their inspiration.[43][44][46]

Construction

_(2).jpg)

Marc Eidlitz & Son, Inc. were hired as the contractors of the new Riverside Drive church.[47] On November 21, 1927, the church's ceremonial cornerstone was laid, marking the start of construction.[47][48][49] The cornerstone featured items such as Woelfkin's Bible and New York Times articles about the new church.[48][50] The Park Avenue church building, as well as three adjacent rowhouses, was sold for $1.5 million in April 1928.[47] The same month, the Park Avenue Baptist Church's official monthly newsletter announced that its existing 53-bell carillon would be expanded to 72 bells upon its relocation to Riverside Drive, making it the largest set of bells in the world.[51]

Three fires occurred in late 1928 after wooden scaffolding around the church was ignited.[52] One of these fires, on December 22, 1928, caused $1 million in damages and almost completely destroyed the interior, though the exterior remained mostly intact. Much of the damages were covered by an insurance policy placed on the building.[53][54] Shortly after the December 1928 fire, Rockefeller announced that he would continue with construction after insurance claims were settled.[55] The fire delayed the completion of the interior by six months.[50][56] In February 1929, the congregation began seeking donations to continue construction. Rockefeller donated $1.5 million, which when combined with the proceeds from the Park Avenue building's sale, provided $3 million in funds.[57] Construction of a mortuary at the Riverside Drive church was approved in March 1929.[58] While construction was ongoing, the congregation temporarily relocated to Temple Beth-El on Fifth Avenue and 76th Street for nine months starting in July 1929.[47]

The first portion of the new church building, the assembly hall under the auditorium, opened in October 1929.[59][60] That December, Fosdick formally filed plans to rename the church from "Park Avenue Baptist Church" to "Riverside Church".[61] The bell was hoisted to the top of the tower's carillon in early September 1930,[62] and the tower was completed later that month, with the first Sunday school class being held there on September 29.[63] The church was completed a week later, on October 5.[47][49][64] On that date, the first service in the altar was attended by 3,200 people, and though all of the space in the nave and basement was filled, thousands more wished to enter.[49][64] The next month, officials received two oil paintings from Rockefeller Jr.'s collection.[65] The first officers of Riverside Church were elected in December 1930[19] and the church was formally dedicated with an interdenominational service two months later.[19][66] The total cost of construction was estimated at $4 million.[67] In the early years of the new building, journalists tended to refer to the church in association with either Rockefeller or Fosdick, although the former sought to reduce emphasis on his role at the church.[68] Riverside Church's completion sharply contrasted with the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, which remained incomplete after almost four decades.[69]

Despite the completion of Riverside Church, Rockefeller felt that the surroundings still needed to be improved.[69] He announced in 1932 that he would pay for a $350,000 landscaping of the adjacent Sakura Park, which at the time stood decrepit.[69][70] Rockefeller hired the Olmsted Brothers to renovate the park,[71] and the project was completed two years later.[72] Additionally, when Union Theological Seminary announced that it would build a new apartment building at 99 Claremont Avenue. Rockefeller offered to exchange his neighboring apartment building at 122nd Street and Claremont Avenue for the lots south of the church, which were owned by the seminary. The land was swapped in 1931 after Rockefeller offered to finance part of the dormitory's construction.[71] In 1935, the land under the church was deeded to Rockefeller,[73] and he also purchased a lot at Riverside Drive and 122nd Street from St. Luke's Hospital, so that he now owned all of the land along the eastern side of Riverside Drive between 120th and 122nd Streets.[74] Ultimately, Rockefeller spent a total of $10.5 million toward land acquisitions and church construction.[68]

Use

1930s through mid-1960s

The completion of the new church building at Morningside Heights resulted in a steady increase in the congregation's membership. By May 1946, the congregation had 3,500 members, 800 more than twenty years previously. According to a brochure issued by the church, "soon every room [...] was in use seven days a week", and enrollment at the church's Sunday school had increased correspondingly.[68]

Riverside Church became a community icon and a religious center of Morningside Heights. By 1939, the church had more than 200 persons on its staff in both part-time and full-time positions, and over 10,000 people a week were being served by the church's various social and religious services, athletic events, and employment programs.[75] In addition to its highly attended Sunday morning service, Riverside Church hosted Communion services every first Sunday afternoon, as well as Ministry of Music services on other Sunday afternoons. The Riverside Guild, the young-adult fellowship, held worship services during Sunday evenings. Weddings and funerals were also hosted at the church.[76] The United States Naval Reserve Midshipmen's School at Columbia started using Riverside Church for services in 1942, drawing 2,000 attendees on average.[68] The Midshipmen's School continued to hold its services at the church until October 1945.[68][77]

In June 1945, Fosdick announced that he would step down as senior minister, effective the following May.[78] This spurred a search for a new pastor, and in March 1946, Robert James McCracken was named for the position.[79] McCracken officially became the senior pastor of Riverside Church that October.[80] As Fosdick and McCracken held each other in mutual respect, the transition between ministers went smoothly.[81] Over the next two decades as senior pastor, McCracken continued Fosdick's policy of religious liberalism.[81][82] Halfway through McCracken's tenure, in 1956, the church conducted an internal report and found that the organizational structure was disorganized, and that most staff did not feel that any single person was in charge. As a result, six councils were created and placed under the purview of the deacons and trustees.[83] The councils partitioned power into "a series of mini-kingdoms", as a later pastor, Ernest T. Campbell, described it.[84]

Construction on the Martin Luther King Jr. Wing, to the south of the existing church, started in 1955. The seven-story wing was designed by Collens, Willis & Beckonert, successors to Allen & Collens; its $15 million cost was funded by Rockefeller.[68][74] The wing was dedicated in December 1959 and contained additional facilities for the church's programs.[68][85][86] A 15-foot (4.6 m) "dummy" antenna had been placed on top of Riverside Church's 392-foot-tall carillon earlier that year, to determine whether it could be used by Columbia University's radio station, WKCR (89.9 FM), though the antenna was strongly opposed by parishioners and the local community.[87] Nevertheless, the church decided to place an antenna atop the carillon for its own radio station, the top of the antenna being 440 feet (130 m) above ground level.[88] Riverside Church started operating the radio station WRVR (106.7 FM) in 1961, and continued to operate it until 1976.[68] Additionally, Riverside Church's congregation voted to merge with the United Church of Christ in 1960.[89] The Stone Gym, a preexisting Union Theological Seminary building southeast of the original church, was purchased by Rockefeller and then reopened as a community facility in April 1962, after a five-year renovation.[90][91] McCracken announced in April 1967 that he would leave his position as senior minister, citing health issues.[92]

Late 1960s through 1990s

Ernest T. Campbell became pastor in November 1968.[93][94] Less than a year after Campbell became senior minister, civil rights leader James Forman interrupted a sermon at Riverside Church, citing it as one of several churches from which black Americans could ask reparations for slavery.[95][96] This led to the church releasing its financial figures for the first time in 1970, which valued the building at $86 million and the total financial endowment of $18 million,[95] as well as the creation of a $450,000 Fund for Social Justice to disburse reparations over three years.[96][97] Further, following a 1972 metropolitan mission study, several ministries were formed at Riverside, aimed toward ameliorating social conditions in the New York City area.[98] Campbell's tenure was marked by several controversial sermons,[96] as well as increasing conflicts among the church's boards, councils, and staff.[93] In June 1976, Campbell resigned suddenly, having felt that his style of leadership was not sufficient to reconcile these disagreements.[93][99] The same month saw the installment of the church's first female pastor, Evelyn Newman.[100]

By a vote in August 1977, William Sloane Coffin was selected as the next senior minister of Riverside Church.[101] Coffin officiated his first service in November 1977.[102] At this point, the congregation's size had been declining for several years. However, after Coffin's selection as senior minister, membership had increased to 2,627 by the end of 1979, and total annual attendance for morning services rose from 49,902 in 1976 to 71,536 in 1978.[103] Coffin's tenure was also marked by theologically liberal sermons, many of which were controversial,[103][104] though he was more traditional in his worship.[104] Coffin announced his intention to resign in July 1987 to become the president of disarmament organization SANE/Freeze,[105] and held his last sermon that December.[106]

Riverside Church formed a committee, which conducted a nationwide search for their next senior minister over the next year. In February 1989, the committee chose James A. Forbes, a professor at nearby Union Theological Seminary, for the position.[107][108] The congregation then voted almost unanimously to approve Forbes's selection, thereby making him the church's first black senior minister.[108][109] At the time, between one-fourth and one-third of the congregation was black or Hispanic.[109] However, tensions soon developed between Forbes and executive minister David Dyson over matters ranging from Forbes's sermon lengths to his musical choices. The tensions grew to the point that a mediator was enlisted after Forbes tried to fire Dyson.[110] The dispute was resolved when Dyson resigned in October 1992.[111]

In 1996, Riverside Church started conducting a study on the building's current use and services,[112] and the following October, Body Lawson, Ben Paul Associated Architects and Planners published their Riverside Church Master Plan.[113] The plan included a major addition on Riverside Church's eastern side, which included the relocation of the Claremont Avenue entrance, paving of the forecourt, reconfiguration of the cloister lobby, and construction of a seven-story building over the gymnasium. This was controversial among many congregants, who started a petition to ask the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (NYCLPC) to designate the church so that the original appearance of that entrance could not be altered.[112] In December 1998, the congregation voted to officially nominate the church for landmark status.[114] The congregation chose to nominate only the original church building, excluding the Martin Luther King Jr. Wing, despite preservationists' requests that the entire structure be considered for landmark designation. The NYCLPC approved landmark status for the original church in May 2000.[115]

21st century

Two controversies involving Riverside Church arose in the early 2000s. The first involved a sexual-abuse allegation against the director of a basketball program at the church, while the second concerned an allegation that the church's finances were being mismanaged due to a $32 million decrease in the endowment between 2000 and 2002.[116] The accused basketball director resigned in 2002,[117] while the controversy over finances was prolonged through several years of court cases, although the New York Supreme Court had dismissed a lawsuit over the topic.[118] Forbes announced his retirement in September 2006[119] and held his last sermon in June 2007. By that time, the church had 2,700 congregants, though the congregation was then primarily black and Hispanic.[120] At that time, the church had a $14 million annual operating budget and a paid staff of 130.[121]

Another nationwide, year-long search commenced, and in August 2008, it was announced that Brad Braxton had been selected as the sixth senior minister of Riverside Church.[122] His tenure was marked by theological disputes, with congregants disagreeing over whether the church should take a fundamentalist or progressive position, as well as a lawsuit over his high annual salary, which a church spokesperson stated was $457,000. In June 2009, he submitted his letter of resignation due to these disputes.[123][124][125] Over the next five years, Riverside Church did not have a senior minister, and its congregation size decreased to 1,670 in 2014, representing a loss of over a thousand congregants since 2007.[126] During this period, in 2012, the church and its annexes were listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[2]

Amy K. Butler was selected as the church's seventh senior minister in June 2014, becoming the first woman to hold that job.[126] In September 2018, it was announced that Riverside would buy the neighboring McGiffert Hall at Claremont Avenue and 122nd Street for $45 million. The dormitory was located on land that had been donated by John Rockefeller Jr. to the Union Theological Seminary, and under the donation agreement, the church had the right of first offer to buy the building should it ever come up for sale.[127][128] In July 2019, the church's governing council announced that Butler's contract would not be renewed. At the time, the Church Council and Butler released a joint letter stating that Butler's resignation was mutual. A former church council member later described how Butler was fired after she and several other female staff members had been the victim of sexual harassment by another former council member, Dr. Edward Lowe.[1][129] The former council member claimed that despite the Council previously launching an extensive investigation into Lowe's conduct, the Council had not conducted as thorough of an investigation into allegations against Butler before voting to break off contract negotiations.[130] However, media outlets later reported that Butler had taken subordinate staffers to a sex-themed shop during a conference in Minneapolis, and in so doing, bought female subordinates vibrators and waved a church credit card as she paid for the spree.[131]

Design

Riverside Church takes up a 454-by-100-foot (138 m × 30 m) lot[132] between Riverside Drive to the west, 122nd Street to the north, Claremont Avenue to the east, and 120th Street to the south.[133] Riverside Church's main architects, Henry C. Pelton, Francis R. Allen, and Charles Collens, created the general plan for the church.[3] Pelton was most involved with tactical planning, while Collens was most involved in the Gothic detail.[41] Sculptural elements were designed by Robert Garrison and carried out by local studios such as the Piccirilli Brothers,[44][134] while the interior was designed by Burnham Hoyt.[47][135] The Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) Wing to the south of the original building was designed by Collens, Willis & Beckonert, while the Stone Gym to the southeast was designed by Louis E. Jallade.[90] As of 2017, Riverside Church is the tallest church in the United States (and among the tallest churches in the world),[136][137] with a tower rising 392 feet (119 m).[41][43][51]

Pelton and Collens chose a Gothic architectural style for Riverside Church's exterior; by contrast, the internal structure incorporated modern curtain walls and a steel frame.[44][138] Fosdick later said that the exterior Gothic style was suited to "make people pray", and that the church had "not outgrown Gothic" in that regard.[139] Riverside Church's design is partially derived from France's Chartres Cathedral, but also draws from several Gothic churches in France and Spain.[43][140] Pelton and Collens said that Chartres would provide the "fundamental principles" for the design of Riverside Church, but that Chartres and Riverside would have a completely different outline.[44][46] The features inspired by Chartres included the detailing of the three Riverside Drive entrances, as well as the lack of decorative elements on the facade, except for the stained glass windows on the walls and the sculptural elements around each portal. The massive single bell tower was inspired by the two western towers at Chartres.[43][44] The rest of the facade consists of Indiana Limestone.[132]

Upon Riverside Church's completion, its design received both praise and criticism.[68] The American Architect published pieces in mid-1931 that featured a critical viewpoint from Columbia architecture professor Walter A. Taylor, and a rebuttal from architect Charles Crane, who had worked on the project with Pelton. While Taylor believed that the design should have been more modernist,[138][141] Crane defended Pelton's Gothic design as being "fundamentally Christian".[138][142] The writers of the 1939 WPA Guide to New York City said that the tower's features make the "building itself seem smaller than it is, so that its scale is scarcely impressive, even when seen at close range."[75] Other critics called the building's exterior overly opulent,[143] and one critic stated that when considered along the progressive ideology, the Gothic design "can only be interpreted as an outward confession that religion is dead."[49] Conversely, The New York Sun referred to the building as among the "most outstanding additions" to New York City's church architecture "in recent years".[144] Eric Nash, in his book Manhattan Skyscrapers, called Riverside Church "Manhattan's last great eclectic skyscraper",[133] while the AIA Guide to New York City dubbed the church "easily the most prominent architectural work along the Hudson (River) from midtown to the George Washington Bridge".[143]

Architectural features

Main building

The main structure is centered around the church's nave, which is aligned on a north–south axis, closer to Riverside Avenue on the western portion of the block. The chapel and narthex are located to the south, closer to 120th Street, while the chancel (which contains the altar) and ambulatory are located to the north, closer to 122nd Street.[132]

Facade

The western facade of the nave runs along Riverside Drive.[132][145] At the time of Riverside Church's construction, the church did not own the lots along 120th Street to the south. As a result, the three entrances are on the west, facing Riverside Drive, rather than at the back of the nave to the south, as in other churches. The entrances are located atop a small flight of steps leading from the street.[44][45] The west-facing main entrance, below the tower's base, is through a set of double wooden doors with recessed wooden panel.[132] The figures sculpted in the concentric archivolts of the doorway represent leading religious, scientific, and philosophical figures, while an elaborate tympanum is located below the arches (see § Sculpted elements).[44][146] To the south is the entrance to the narthex, which contains a single door.[147] Directly south of the narthex entrance is another double-door entrance leads to the chapel,[147][148] and contains two archivolts and a simpler tympanum.[132][145][148] The northern portion of the western facade, adjacent to the nave, contains five sets of windows (see § Nave).[47][149]

The view of the southern facade is mostly blocked by the MLK Wing to the south. The top portions of four narrow, arched stained-glass windows can be seen above the hip roof of the structure that connects the two sections. Above these stained glass windows are three recessed, arched windows topped by a pediment containing a circular window.[132][145]

The eastern facade is similar to the western facade, in that it also has five groupings of windows facing the nave.[47][149] However, much of this facade is blocked by McGiffert Hall, which faces directly onto Claremont Avenue and 122nd Street.[150][151] On the eastern facade of the nave is a cloistered passageway leading to Claremont Avenue (see § Cloister passageway).[90][150] A rose window is located on the eastern facade above the cloister section.[132][145]

The northern facade surrounds the chancel and ambulatory. An arched entrance called the "Woman's Porch" is located in the western (left) portion of the north facade and contains carvings of biblical women. Above the entrance arch is an ornate belt course, followed by two lancet windows.[150][152] Another entrance is located in the eastern (right) portion of the north facade.[152] Between the two entrances is the ambulatory, with two tiers of window groupings, each with a rose window above a pair of lancet windows. The lower section has three sets of windows, while the upper clerestory section has five sets of windows. Vertical buttresses, which separate each window grouping, end in finials above the roofline.[150][152]

Nave

The nave takes a Gothic model inspired by France's Albi Cathedral,[153] and measures 100 feet (30 m) high by 89 feet (27 m) wide and 215 feet (66 m) long.[154] The width between the overhanging clerestory walls is 60 feet (18 m).[153][154][138] The low and wide form of the nave is inspired by southern French and Spanish churches.[155] The nave contains a metal roof, whose base is surrounded by a shallow arcade.[132] Its interior contains an Indiana limestone finish, while the ceilings of its vaults are lined with Guastavino terracotta tiles, and its floor is made of marble.[154]

The nave's western and eastern walls comprise three main vertical sections, which are split by buttresses.[132] Along the bottom portion of the nave (adjacent to the aisles), there are five architectural bays each on the western and eastern walls, with each bay containing a pointed-arch window.[47][149][156] Above the stained-glass windows, each bay contains a triforium gallery with three colonettes, followed by two adjacent lancet windows in the clerestory, and topped by a rose window.[132][156][157] Pointed arches, resting on piers that contain engaged columns, support each of the clerestory bays as well as serve as the bases for the ribs under the vaulted ceiling.[154] The engaged columns are surmounted by Corinthian capitals that are decorated with scenes from the Book of Jeremiah. The ceilings of the vaults underneath the triforium galleries are faced with Guastavino tile,[156] and contain lighting.[158]

The ceiling of the nave, above the clerestory, is eight stories high.[159][160] It consists of several vaults, which are each divided into four segments by diagonally interlocking transverse ribs, which do not provide structural support.[156] Eight iron lanterns hang from the transverse ribs and descend to below the level of the triforium gallery.[158] The vaults contain a finish of acoustic Guastavino tiles, which are mostly gray.[156] The tiles above the chancel and the nave's northernmost two bays are brown, because a sealant was applied in that section in 1953 to increase the acoustical reach of the organ, and had turned yellow over time.[158]

The nave was built with a seating capacity of either 2,408[67] or 2,500.[41] The ground level contains 38 rows of pews, made of oak wood with Gothic decoration, although five additional rows of pews used to exist at the front of the nave.[158] Two seating galleries overhang the back (southern portion) of the nave.[158][159] The lower gallery is made of carved wood, with rows of oak pews on a downward slope, and contains a wooden ceiling with nine lamps. The upper gallery is also made of carved wood and contains oak pews on a slope, but does not contain a canopy above it.[161] The upper gallery is illuminated with four lanterns, similar to the eight above the main section of the nave. Behind the southern wall are six double-tiered niches with stone sculptures of ministers and Jacob Epstein's Christ in Majesty sculpture. The Trompeta Majestatis organ projects from the wall beneath the niches.[162]

Chancel, ambulatory, and apse

The chancel is located directly to the north of the nave and is raised by a few steps. A limestone railing with 20 quatrefoil medallions separates the chancel and the nave. The western portion of the rail contains a pulpit with a wooden canopy and three carved limestone blocks.[158][163] A labyrinth composed of three types of marble, inspired by a similar design at Chartres Cathedral, is inlaid in the middle of the chancel floor. Flanking the labyrinth on either side are four rows of choir stalls, made of oak with carvings of Psalms texts.[158][164] Behind the choir stalls (to the north) is the organ console.[164] A communion table of Caen stone is located toward the back of the chancel, in the center. A baptismal pool is located behind the communion table.[164][161]

The back of the chancel contains a convex polygonal wall. The wall includes seven bays, each with three vertical tiers that are a few feet above the corresponding tiers in the nave. The bottom tier contains pointed arches with an elaborate stone chancel screen; the middle tier contains cusped arches with colonettes; and the top tier serves as the clerestory.[158] The three center bays behind the chancel screen each contain one window group on the lower tier. These window groups each contain two lancet windows topped by a rose window, and are divided by vertical buttresses. The apse clerestory, the upper section of the ambulatory, is recessed slightly inward. The upper section's fenestration is similar in form, in that it each window grouping contains a rose window above a pair of lancet windows, but the window groupings are located on five sides of the polygon.[150][152] The vertical piers of the chancel wall converge above the clerestory level, creating an apse above the chancel and ambulatory.[161]

Narthex

The narthex, designed in the late Gothic style with a Romanesque layout,[147] is located directly south of the nave and can be accessed from the church's West Portal. The narthex is split into four vaults with Guastavino tiled ceilings, supported by simple limestone columns.[147][154] A stone spiral staircase on the west side of the narthex, directly south of the West Portal, leads down to the basement.[154] There are two grisaille windows and one rose window on each of the western and eastern sides of the narthex.[157] The eastern wall contains four 16th-century lancet windows, previously located in the Park Avenue Baptist Church and were the only windows in Riverside Church not built specifically for the church.[147][156] Stairs leading both upward and downward are located on the eastern side of the narthex, while a mortuary chapel is located on the northeastern corner.[156] The mortuary chapel is known as the Gethsemane Chapel, but prior to 1959 was called the Christ Chapel.[154][lower-alpha 2]

Chapel

The chapel to the south of the narthex, known since 1959 as the Christ Chapel,[147][162][lower-alpha 2] was inspired by the Basilica of Saints Nazarius and Celsus in France.[147] Its design was inspired by Carcassonne Cathedral's pointed Romanesque nave. Described by architectural historian Andrew Dolkart as "earlier than Gothic", the design is intended to give the impression that the rest of the sanctuary was built after the chapel.[138] The chapel is subdivided into four bays and has a barrel-vaulted ceiling with Guastavino tiles, while the walls and floor contain a limestone finish. The southern wall, adjacent to the MLK Wing, contains four arched, back-lit stained-glass windows, one in each bay. Double doors to the west lead to Riverside Drive while a passage to the south leads to the MLK Wing.[162] There are engaged columns on the north and south walls between each of the four bays, as well as eight lanterns hanging from the columns.[166]

The eastern end of the chapel contains an altar, located four steps above the main level of the chapel. There is a lectern to the right of the altar and a pulpit to the left.[166][167] Several sculpted representations are located above the altar.[167] A baptismal pool and a reredos are located behind the altar, through an arched opening, while an alcove to the narthex is located to the left (north) of the altar.[166]

Tower and carillon

.jpg)

The 392-foot (119 m) tower was named after Laura Spelman Rockefeller, the mother of John D. Rockefeller Jr.[41][43][51] The tower contains 21 usable floors, which include 80 classrooms and office rooms.[68][168] There are four elevators in the tower, two that rise only to the 10th floor, and two that go to the 20th floor.[166][168] The 20-floor-tall elevators, rising 355 feet (108 m), were described in 1999 as the world's tallest elevators inside a church.[133] Two staircases ascend from ground level: one on the western side of the tower, which ends at the ninth floor, and one on the eastern side, which continues to the carillon.[166] Balconies are located at either southern corner on the 8th floor, and on all sides of the 10th floor except the north side.[160]

On the western elevation of the tower's base is the main entrance, flanked by projecting vertical piers (see § Facade). Seven arched niches, each containing statues of kings, are located above the main entrance. A large rose window is located above the statuary grouping.[132] The top of the tower is fitted with aircraft warning lights.[133] Above the tenth floor, there are five tiers of window arrangements on each floor, with higher tiers being progressively narrower. From bottom to top, the successive tiers contain 2, 4, 3, 4, and 5 windows on each side. There are narrow canopied niches in each corner of the tower, with one statue inside each niche. At the top of the tower is a conical metal roof.[150][152]

Tower stories

Most of the tower's stories consist of plaster floors, steel doors, steel window frames, and iron lighting fixtures hanging from each ceiling. There are elevator lobbies with vaulted ceilings on several stories of the tower. On the stories that contain common spaces, including the 9th and 10th floors, the floors are finished with stone, terrazzo, and wood, with wooden doors. Over the years, several spaces have been used by outside entities, who carpeted floors and installed fluorescent lighting fixtures in some office rooms.[160]

Originally, the 4th through 14th floors held Riverside Church's school, while the 15th floor and above contained various staff and clergy offices, as well as spaces for group activities.[159] The 2nd floor connects to the nave's lower seating gallery, while the 3rd floor leads to the upper seating gallery. The 4th through 8th floors are located below the height of the nave's ceiling, and contained the nursery, junior high, and high school departments of the church's school. The 9th and 10th floors included the double-story school kitchen, school offices, and storage rooms over the nave.[159][160] The 9th floor also includes a library and wooden furniture in both the kitchen and library.[160] The main structure's roof is located above the 10th floor, and the tower rises independently above that point.[159][160] The 11th through 14th floors originally contained the church's elementary school, while the 15th and 16th floors respectively contained the young people's meeting room and the social room.[159] These were later converted into office space, with several floors subdivided and leased out.[160] The 17th through 20th floors include meeting rooms, though the 17th floor also contains offices. The 21st floor includes the carilloneur's studio, and the 22nd floor is devoted to mechanical space.[159][160]

Carillon

The 23rd floor of the tower contains a three-level belfry.[166] The belfry houses a carillon whose final complement of 74 bronze bells, at the time of construction the largest carillon of bells in the world, includes the 20-ton, 122-inch-diameter (3.1 m) bourdon, the world's largest tuned bell.[68][169] Though other carillons with more bells have been commissioned,[lower-alpha 3] Riverside Church's carillon is still the largest in the world by aggregate weight: the bells and associated mechanisms weight a combined 500,000 pounds (230,000 kg).[68][143] Of the carillon's bells, 53 were made for the original Park Avenue church by English founders Gillett & Johnston.[51][68][160] Another 19 were made for Riverside Church when it opened,[68][160] and two additional bells were added in 1955, whereupon 58 treble bells were replaced by bell founders Van Bergen.[160] The bells were replaced again by Whitechapel Bell Foundry in 2004.[160] The bells can reportedly be heard from a distance of up to 8 miles (13 km).[66][68]

A mechanical power room and control room are located in the belfry, while the clavier cabin is located at the top, above the carillon.[172] Due to the weight of the carillon, the heaviest steel beams used in the construction of Riverside Church were used in the tower. The north facade, which overhangs the nave, is supported by a single cross truss that weighs 60 short tons (54 long tons; 54 t).[168] Outside the carillon, the facade of the tower contains ornate Neo-Gothic detailing, with features such as gargoyles.[150][152] There was also a public observation deck on top of the carillon.[143][172] The deck was closed after the September 11, 2001, attacks due to security concerns,[143][172] but the church resumed tours in January 2020.[173]

Cloister passageway

The cloister passageway leads from the southern portion of the nave to Claremont Avenue in the east. It contains four pointed-arch bays, each with a Corinthian-style colonette topped by a grisaille window opening on the south wall.[150][151] The north and south walls also contain stained-glass windows, though the north wall's windows are artificially illuminated. Inside the cloister passageway are five vaults, illuminated by six lanterns.[172] The entrance to the passageway is a small two-story structure with two arched doorways facing Claremont Avenue, and a set of double doors facing a short wheelchair ramp to the south. The top of the cloister entrance's eastern facade contains three niches with figures of Faith, Hope, and Charity, while the southeast corner contains a figure of Maaseiah.[151][174] There is also a gift shop adjacent to the cloister passageway, while sculptures of the architects and builder are located above the doorway leading to the tower's base.[172]

Martin Luther King Jr. Wing

The Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) Wing is a seven-story annex located to the south of the main structure, facing 120th Street along the southern boundary of the plot.[86][172] The MLK Wing is shaped like an "L", with the longer arm running north–south adjacent to Riverside Drive, and the shorter arm running west–east next to 120th Street. It connects to the original church building to the north and the Stone Gym to the east. The area between the MLK Wing and the cloister form a small courtyard or garth, which is enclosed on the east by a metal fence.[172] Inside are children's chapels, space for the school, a rooftop recreation area, space for a radio station, community areas such as a gymnasium and assembly room, and a basement with a parking lot.[74][86][175]

The structure, designed by Collens, Willis and Beckonert and built by Vermilea-Brown,[74][176] is a simplified version of Allen and Collens' original church design and was perceived as being "modern Gothic".[176] It was known simply as the South Wing until 1985, when it was renamed for civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.[90][113]

Facade

The facade is clad with Indiana limestone, while the foundation is made of stone and concrete, and the structure is supported by a steel frame. The main entrance is through the chapel doors on Riverside Drive to the west, and there are also entrances to the basement from 120th Street.[172] The basement through second floors of the western facade contains eight architectural bays, each with one small lancet window, which are recessed between projecting buttresses and located under a set of arches. The two outermost bays project slightly outward and do not contain recessed arches. The section of the MLK Wing above the second floor is set back from Riverside Drive, and the windows on the third through sixth floors are also recessed between buttressed arches, while the seventh-floor windows are flush with the buttresses. The two outermost bays contain two sets of windows instead of a single window on each floor, and project slightly outward.[148]

The southern and eastern facades are designed in a similar fashion to the upper portion of the western facade, in that the seventh-floor windows are flush with the buttresses, while the windows below are located in recessed arched bays. The southern facade contains eight window bays, six of which are recessed. There are no windows into the first or second floors on the westernmost four bays of the southern facade, but the eastern four bays do contain windows into these floors. On the far eastern portion of the southern facade are two pointed-arched openings that lead to the church's underground parking garage (see § Basement).[177] The eastern facade is separated into two sections. The section at the end of the "L"'s shorter arm contains four recessed window bays. The section next to the north–south axis of the "L" contains six window bays, four of which are recessed.[177]

Interior

The northern arm of the MLK Wing's first floor includes the South Hall Lobby, which includes a two-story-high coffered ceiling supported by a pointed-arch arcade, as well as walls made of gray plaster. An elevator bank and an auditorium called the South Hall are located south of the lobby. The South Hall's walls are made of wood paneling below limestone, and nine stained-glass lancet windows on the western side. Two mezzanine levels below the South Hall's ceiling are located to the east of the auditorium, while a sealed tunnel leading to the Interchurch Center across 120th Street is also accessible from the auditorium.[178]

The third through seventh floors include classrooms, except for the fifth floor, which contains offices.[86][175][178] The floors are made of terrazzo in the hallways and resilient flooring in the individual rooms (except for the fifth floor rooms, which contain carpeted rooms), and each level contains dropped ceilings.[178] Chapels for children are located on the third floor's southwest corner and on the sixth floor's southern side.[86][178] The roof contains a solarium and a play area.[86][179]

Stone Gym

The Stone Gymnasium is a 1 1⁄2-story English Gothic building located at 120th Street and Claremont Avenue, east of the Martin Luther King Jr. Wing. The gym was built in 1912 to a design by Louis E. Jallade and originally was used by the Union Theological Seminary. Its architectural details include a facade of schist with limestone decoration, as well as a metal hip roof.[90] The structure measures five bays long on the eastern facade and one bay wide on the southern and northern facades.[179] In 1957, Rockefeller donated the building to the church, and five years later, it reopened as a gymnasium and community facility.[90][91] The interior contains a basketball court with synthetic flooring, as well as offices and lockers in its northern end.[90]

Basement

Riverside Church's basement includes several modern amenities such as a 250-seat movie theater and a gymnasium with a full-size basketball court.[133] The section of the basement under the nave contains a double-height ceiling; an assembly hall is located on the south side of this space, while the gymnasium is located on the north side. The assembly hall includes a stone floor and stone walls, with six arched stained-glass windows on the eastern wall and one rectangular stained glass window on the south wall, as well as cabinets that contain two Heinrich Hofmann paintings (see § Paintings). It also contains a wooden ceiling supported by stone arches, with lanterns suspended from the ceiling; and a stage in the northern portion. A kitchen is located east of the stage, and a corridor runs adjacent to the western wall of the assembly room and gymnasium.[166]

The basement also originally included a four-lane bowling alley adjacent to the assembly floor.[133][166] It was later removed[133] and converted into storage space.[166] There is also a two-story, 150-space parking lot[74][178] underneath the MLK Wing.[86][133]

Organs

There are two organs in Riverside Church: one in the chancel and the other in the seating gallery.[180] The chancel organ is the 14th largest in the world as of 2017.[181][182] Hook and Hastings furnished the original chancel organ in 1930,[180][183] though it was originally criticized as being mediocre.[183] Aeolian-Skinner built an organ console in the chancel in 1948 and replaced the chancel organ in 1953–1954.[180] At this time, the ceiling above the chancel and the front of the nave was coated with sealant to improve the chancel's acoustic qualities.[158] Another Aeolian-Skinner organ was installed in 1964 within the eastern wall of the nave's seating gallery, and three years later, Anthony A. Bufano installed a five-manual console for the gallery organ.[180] M. P. Moller built another organ for the gallery, the Trompeta Majestatis, in 1978.[162][180] Two years later, the chancel received a new principal chorus, with the addition of the Grand Chorus division. In the 1990s, the console was rewired, the chancel organ was cleaned, and the ceiling was covered with ten sealant layers.[180]

The Director of Music and organist is Christopher Johnson as of 2019.[184] Past organists at the Riverside Church have included Virgil Fox (1946–1965),[185] Frederick Swann (1957–1982),[186] John Walker (1979–1992),[187] and Timothy Smith (1992–2008).[188]

Art and sculpture

Paintings

Riverside Church contains paintings by Heinrich Hofmann that were purchased by Rockefeller Jr. and donated to the church in November 1930.[65] Christ in the Temple (1871) and Christ and the Young Rich Man (1889) are located in the assembly hall beneath the nave and are usually locked within the cabinets there.[166] Hofmann's Christ in Gethsemane (1890) is located in the Gethsemane chapel.[152]

Stained glass

Riverside Church's main building contains 51 stained glass windows, excluding smaller grisaille windows.[157] These were created in a mosaic style, which was becoming more popular at the time of the church's construction.[47] Of these, 34 windows are located in the nave, most of which contain religious iconography. Generally, the "richer"-colored windows were located on the western side, considered the "light" side, while the more muted colors were located on the eastern "dark" side.[157]

Two French glassmakers, Jacques Simon from Reims Cathedral and Charles Lorin from Chartres Cathedral, were hired to create the glass for the clerestory windows in the nave.[47][149][156] Lorin designed the stained-glass windows on the western side of the clerestory while Simon designed the windows on the eastern side. Both sets of windows depict general religious and government themes, and they incorporate secular iconography as well as depictions of non-Christians.[156] The clerestory windows closely resemble those at Chartres, and contain a rose with lancet windows.[47][149] The other windows in the nave were created by Reynolds, Francis and Rohnstock, a Boston-based firm, and depict over 138 scenes from both religious and non-religious contexts.[47][156] The three groups of stained glass windows in the apse were created by Harry Wright Goodhue,[47] as were the nine stained glass windows in the South Hall.[178]

Mosaics

Gregor T. Goethals created two mosaics for the fourth and seventh floors of the MLK Wing. The fourth-floor mosaic shows the Old Testament while the seventh-floor mosaic shows the Creation.[178]

Sculpted elements

Exterior elements

.jpg)

The most prominent sculptural details are located on the Riverside Drive facade. The main entrance, located beneath the tower, is topped by five concentric archivolts, with sculptures of Jesus's followers and prophets inlaid within each section of the archivolts.[44] The third arch of the main entrance contains depictions of philosophers including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Immanuel Kant, and Pythagoras, while the second arch depicts scientists like Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin, and Hippocrates.[44][49] Other figures depict the 12 months of the year.[146] The columns framing the door jambs, located under the archivolts, are also decorated with capitals and gargoyles at the top and bottom, and a single figure in the middle. A seated figure of Christ is located in the tympanum above the doors and below the archivolts, and is flanked by the symbols of the Evangelists.[132][145]

When Riverside Church was completed, there was controversy over the inclusion of Einstein, a Jewish man who was still alive when the church was constructed, as the other figures represented figures who had since died.[149][189] The publication Church Monthly said that during construction, the committee tasked with the church's iconography had proposed 20 scientists to be depicted on the facade, of which Einstein was not part.[189] However, the faculty had unanimously decided that Einstein should be included, as he was indisputably one of 14 "leading scientists of all time".[149]

The chapel entrance, located on Riverside Drive south of the main entrance, contains two archivolts supported by two sets of columns. The archivolts contain symbols of the zodiac, and the second archivolt contains an elaborate decorative molding. A tympanum relief below the archivolts depicts the Virgin Mary flanked by two angels who are mirror images of each other.[132][145]

In addition, sculpted elements are placed within niches spread across the church's facade. Above the main entrance on the western facade, there are sculptures of seven kings.[132] More statues are located within niches in the tower itself,[150][152] as well as in niches on the facade of the cloister entrance to the east.[151][174] Also placed on the facade are gargoyles, located outside the carillon near the top of the tower.[150][152] The northern section of the nave's roof contains a bronze statue, Angel of the Resurrection, which depicts a trumpeter atop a pedestal.[132]

Interior elements

The various carvings inside different portions of the church correspond to the respective uses of these portions. For instance, the 20 quatrefoil medallions inscribed on the chancel railing depict the typical "interests, emphases, activities, rites, and ceremonies" that are conducted within the chancel.[164] Around the pulpit are ten Old Testament prophets.[158][164] Above the nave, the southern wall of the upper seating gallery contains multi-tiered niches, whose upper tiers contain sculpted figures of ministers. The center two niches contain a cast of Epstein's gilded-plaster sculpture Christ in Majesty.[162]

There is a seven-paneled chancel screen at the back of the chancel, carved in Caen stone.[158] It depicts numerous influential figures such as the composer Johann Sebastian Bach, the U.S. president Abraham Lincoln, the artist Michelangelo, the social reformer Florence Nightingale, and the author Booker T. Washington.[47][161] From left to right, the panels depict physicians, teachers, prophets, humanitarians, missionaries, reformers, and lovers-of-beauty.[161][190]

Above the doorway between the cloister and the tower base are statues of architects Henry Pelton and Charles Collens, as well as general contractor Robert Eidlitz.[172]

- Carving details

Stone carving detail

Stone carving detail Several sculptures like these adorn the church

Several sculptures like these adorn the church- Sculpted figures inside the gallery

Social services

The church was conceived as a complex social services center from the outset, with meeting rooms and classrooms, a daycare center, a kindergarten, library, auditorium and gym. It was described by The New York Times in 2008 as "a stronghold of activism and political debate throughout its 75-year history ... influential on the nation's religious and political landscapes."[122] Riverside Church continues to provide various social services, including a food bank, barber training, clothing distribution, a shower project, and confidential HIV tests and HIV counseling.[193] In 2007, the Times said that Riverside has frequently "been likened to the Vatican for America’s mainstream Protestants."[121]

Social justice ministries

Charity and shelter

Riverside has two prisoner-related ministries. Riverside's Prison Ministry and Family Advocacy Program conducts worship services in the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision; helps prisoners and their families; links prisoners to their communities; holds various workshops, support groups, and events; and lobbies for prison reform and humane legislation.[194] Riverside's Coming Home ministry helps prisoners after they have been released.[195] The prison ministries date from 1971, when the Council on Christian Social Relations created a prison reform and rehabilitation task force.[196]

Riverside's Coming Home ministry, founded in 1985, deals with homelessness in New York City.[195] Riverside's advocacy of the homeless originated from a similar ministry, the Clothing Room and Food Pantry, which was a subdivision of the Social Services Department. The church began sheltering homeless people overnight from 1984 until 1994, when it was closed due to the decreasing homeless population and a staff shortage.[197]

Riverside participated in the Sanctuary movement during the 1980s, being among numerous congregations nationwide that sheltered and assisted undocumented immigrants.[198] As part of the New Sanctuary Coalition, volunteers at Riverside Church and other participating houses of worship assist detained asylum seekers and those on parole from immigration detention.[199] In 2011, as part of a movement called Occupy Faith, Riverside Church donated tents to Occupy Wall Street protesters, as well as sheltered them during cold or inclement weather and after the evacuation of Zuccotti Park.[200]

Social and cultural

Riverside Church's LGBT ministry is named Maranatha.[201][202] It was founded in 1978 in response to growing demand from gay and lesbian congregants.[203] Maranatha hosts several activities, workshops, and events, and marches annually in the NYC Pride March.[203][204] In the 1980s, when the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City was at its peak, there was some backlash against Maranatha, as the LGBT community was negatively associated with the epidemic. These events led to the founding of the separate HIV/AIDS ministry,[205] which hosts a support forum; provides testing, counseling, and referral programs; and collaborates with several other programs.[193]

Riverside Church's African Fellowship and Ministry sponsors educational forums about issues facing the continent of Africa and advocates on behalf of African diaspora.[193] The Sharing and Densford Funds advocate on behalf of Native Americans in the United States.[206] Other ministries at Riverside include support groups for South Africans and for Hispanic and Latino Americans.[193]

Other activism

Riverside has several other social justice ministries. The Beloved Earth ministry is an environmentalist ministry with a focus on climate change activism.[207] The Wellbotics ministry helps the families of cancer patients.[208] Riverside also has several pacifist task forces. The Anti-Death Penalty Task Force is in opposition to capital punishment in the United States. An "Overcoming Violence" task force is dedicated to fostering dialogue with the New York City Police Department.[193] Riverside Church also participates in the National Religious Campaign Against Torture.[209]

Former programming

When Riverside Church's Martin Luther King Jr. Wing was completed in 1959, it included space for a radio station planned by the church.[86] The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) granted the church a FM broadcasting license in 1960,[210] and the following year, Riverside Church started operating the radio station WRVR (106.7 FM).[68][211][212] WRVR originally broadcast from Riverside Church's carillon before being relocated to the Empire State Building in 1971 to increase the range of the broadcast signal. Originally a noncommercial station, WRVR broadcast sermons, as well as programming from cultural and higher-education institutions in New York City.[213] However, WRVR incurred a net loss for Riverside Church each year, and in 1971, was turned into a "limited commercial operation", which also failed to be profitable.[214] Riverside Church decided to sell its radio station in 1975,[215][216] the sale being finalized the following year.[214][217]

Starting in November 1976, Riverside Church hosted the Riverside Dance Festival. The program was a continuation of previous dance ministries hosted by the church, and normally offered 34 weeks of programming from over 60 dance companies.[218] The program ended in June 1987 because of a $900,000 funding shortfall.[219]

Called senior ministers

In chronological order, the called senior ministers at Riverside Church have been:

Notable speakers

On April 4, 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech at Riverside called Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence, where he voiced his opposition to the Vietnam War.[223][224][225] The Rev. Jesse Jackson gave the eulogy at Jackie Robinson's funeral service in 1972.[226] Nelson Mandela, anti-apartheid activist and later South African president, spoke at Riverside in 1991 following his release from prison.[227] Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan spoke there after the September 11, 2001 attacks,[228] and former U.S. president Bill Clinton spoke at the church in 2004.[229][230] Speakers have also included theologians such as Paul Tillich, who taught nearby,[231] as well as Reinhold Niebuhr.[227] Other past speakers include civil-rights activists Cesar Chavez;[227] human-rights activist Desmond Tutu;[227][232] Cuban president Fidel Castro;[233] the 14th Dalai Lama;[120] and Abdullah II of Jordan.[120]

See also

- List of Baptist churches

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan above 110th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan above 110th Street

References

Notes

- These firms included McKim, Mead & White, Allen & Collens, Henry C. Pelton, Ralph Adams Cram, and York and Sawyer.[35]

- There are two chapels that have been known as the Christ Chapel: the mortuary chapel, which was once known as the Christ Chapel, and the main chapel, which was the second to receive the name Christ Chapel.[165]

- The carillon at Hyechon College in Daejeon, South Korea, contains 78 bells.[170] Kirk in the Hills in Bloomfield Township, Oakland County, Michigan, contains 77 bells.[171]

Citations

- Rojas, Rick (July 11, 2019). "Pastor's Exit Exposes Cultural Rifts at a Leading Liberal Church". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- "National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2012" (PDF). U.S. National Park Service. December 28, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2000, p. 1.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2000, p. 2.

- Pendo 1957, p. 9.

- Pendo 1957, p. 22.

- Nevins, A. (1940). John D. Rockefeller: The Heroic Age of American Enterprise. John D. Rockefeller: The Heroic Age of American Enterprise. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 455. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Paris et al. 2004, p. 18.

- Pendo 1957, p. 40.

- "Fifth Av. Baptists Sell Church Home; Property, Long in the Market, Is Purchased by Michael Dreicer". The New York Times. May 30, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- "New Apartment For Park Avenue; Two Large Parcels Acquired at the Southeast Corner of Sixty-third Street". The New York Times. November 6, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- "Rockefeller Aids New Church Fund; Offers to Add 50 Per Cent. to Amount Raised by Fifth Av. Baptist Congregation". The New York Times. May 8, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- "Final Service Held In 5th Av. Church; Dr. Cornelius Woelfkin Reviews Baptist Congregation's History of 91 Years". The New York Times. April 3, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- "Rockefeller Class In New Home Today; Park Avenue Baptist Church Will Occupy Edifice of 64th Street for the First Time". The New York Times. April 9, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Dolkart 1998, pp. 70–71.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 72.

- "Dr. Woelfkin Quits Park Avenue Pulpit; Resigns After 40 Years in Baptist Ministry, 13 of Which Were at His Present Post". The New York Times. May 11, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2000, p. 3.

- Paris et al. 2004, p. 19.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 73.

- "Dr. Fosdick Called By Park Av. Baptists Insists On Changes; Stipulates That Church Shall Not Demand Baptism by Immersion". The New York Times. May 16, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Miller 1985, p. 162.

- "Dr. Fosdick Accepts Call; Will Create A Liberal Church". The New York Times. May 29, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 383, note 157.

- Pendo 1957, p. 49.

- Miller 1985, p. 201.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 383, note 157.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 1.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2000, p. 4.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 74.

- "Rockefeller Jr. Buys Plot Uptown; Block on Morningside Drive Considered Logical Location for Edifice Asked by Fosdick". The New York Times. May 26, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- "Fosdick's Church to Go Up on Drive; Rockefeller Exchanges Morningside Plot for Site Near Grant's Tomb". The New York Times. July 25, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- "Rockefeller Adds to Plot for Church; Acquires Twelve-Story Apartment House on Riverside Drive, Making Frontage of 250 Feet". The New York Times. August 8, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 75.

- Dolkart 1998, pp. 75–76.

- Miller 1985, p. 204.

- "Straton Criticizes Fosdick's Church; Thinks It Means Rockefellers Hereafter Will Have Their Own Sanctuary". The New York Times. June 8, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Chappell, George S. (T-Square) (November 29, 1930). "The Sky Line". The New Yorker. 6: 82.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 76.

- "Rockefeller Plans $4,000,000 Church On Riverside Drive; 400-Foot Gothic Campanile Will House the Carillon, Close to Grant's Tomb". The New York Times. February 12, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 77.

- "Rockefeller Plan for Church is Filed; $4,000,000 Edifice of Park Av. Baptists Will Rise on Riverside Drive". The New York Times. November 2, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- "Baptists Approve $4,000,000 Plans For Fosdick Church; Razing Starts on the Site for Edifice to Be Built to Endure for Generations". The New York Times. December 27, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2000, p. 5.

- Carder 1930, p. 5.

- Carder 1930, p. 9.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2000, p. 6.

- "Cornerstone Laid For Fosdick Church; Hundreds Witness Ceremony in Drive at Foundation of $4,000,000 Edifice". The New York Times. November 21, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 80.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2000, p. 12.

- "Largest Chimes for Park Avenue Church". Democrat and Chronicle. April 24, 1928. p. 4. Retrieved November 8, 2019 – via newspapers.com

- "Rockefeller Pays Visit to Ruins at Church Fire". New York Daily News. December 23, 1928. p. 318. Retrieved November 5, 2019 – via newspapers.com

- "Night Fire Sweeps Riverside Church As 100,000 Look On; Flames Raging In Rockefeller's Riverside Church". The New York Times. December 22, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- "Fire Guts 'Rockefeller Church'; Huge Edifice Reduced to Black Shell". Brooklyn Citizen. December 22, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved November 5, 2019 – via newspapers.com

- "Rockefeller Church To Resume Building; Work to Proceed on Burned Riverside Edifice as Soon as Insurance is Settled". The New York Times. December 24, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- Miller 1985, p. 208.

- "Seek Gifts to Build Riverside Church; Trustees, Planning Endowment Fund, Say Contributions Will Be Welcomed". The New York Times. February 19, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- "Mortuary Chapel in Riverside Church; Rockefeller Approves Feature for New Edifice of Park Avenue Congregation". The New York Times. March 23, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- "First Unit Opened In Riverside Church; Pre-Communion Service Is Held in Assembly Hall of New Rockefeller Edifice". The New York Times. October 3, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Miller 1985, p. 205.

- "Fosdick Church Drops Baptist From Title; Changes Name to the Riverside Church". The New York Times. December 12, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- "Will Hoist 22-Ton Bell; Riverside Church to Complete Carillon on Tuesday". The New York Times. September 7, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "Memorial Tower Opened; Riverside Church Sunday School Classes Held There". The New York Times. September 29, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Paris et al. 2004, p. 137.

- "Reveal Rockefeller Gift; Riverside Church Executives Tell of Receiving Two Paintings". The New York Times. November 1, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "Riverside Carillon is Heard Miles Away; Notes of 72 Bells Ring Out as Denominational Leaders Laud Spirit of Church". The New York Times. February 12, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- "Riverside Church Puts in Pew Phones; Equipment Available to Aid Hearing in All Parts of New Edifice". The New York Times. September 27, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2000, p. 7.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 81.

- "Claremont Park to be Beautified; Rockefeller to Pay $350,000 for Improvement of City Plot at Riverside Church". The New York Times. February 9, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 82.

- "Claremont Park is Opened to Public; Two-Acre Tract on Riverside Drive Improved by Rockefeller at Cost of $315,000". The New York Times. May 26, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- "Riverside Church Deeded; Formal Transfer of Land by Rockefeller Is Placed on Record". The New York Times. June 16, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Dolkart 1998, p. 83.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). "New York City Guide". New York: Random House. pp. 387–389. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.)

- Paris et al. 2004, pp. 67–70.

- "Navy School Thanks Riverside Church". The New York Times. October 22, 1945. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- Studio, The New York Times; 1943 (June 6, 1945). "Fosdick to Quit Riverside Church; Retirement Date Set for May, 1946; Announcement Made at Joint Meeting of Deacons and Trustees--Founder and Pastor of the Church Since 1930". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- McDowell, Rachel K. (March 28, 1946). "Riverside Church Names New Pastor; in New Riverside Church Offices". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- "Riverside Church Installs Pastor; New Riverside Church Pastor Installed". The New York Times. October 3, 1946. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- Paris et al. 2004, pp. 74–75.

- Paris et al. 2004, p. 34.

- Paris et al. 2004, pp. 43–44.

- Paris et al. 2004, p. 46.

- "New 8-Story Wing Opens at Riverside". The New York Times. December 7, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Dedicate Riverside Church Wing". New York Daily News. December 7, 1959. p. 165. Retrieved November 9, 2019 – via newspapers.com

- "Riverside Church Is Aroused By Trial Radio Aerial on Roof". The New York Times. January 9, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Shepard, Richard F. (December 28, 1960). "New FM Station on Air Here Jan 1; WRVR Will Be Sponsored by Riverside Church". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Riverside Church Acting on Merger; Meets to Ratify Constitution of United Church of Christ -- 2d Consolidation Urged". The New York Times. December 8, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- National Park Service 2012, p. 3.

- Paris et al. 2004, p. 255.

- Dugan, George (April 24, 1967). "Dr. McCracken to Leave Pulpit After Two Decades at Riverside". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Paris et al. 2004, pp. 45–47.

- Dugan, George (November 18, 1968). "Dr. Campbell Is Installed at Riverside Church; Predecessor, Dr. McCracken, Gives Him the Charge Dr. Marney Calls in Sermon for 'Vast Repentance'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Riverside Church Has Money Woes". The New York Times. February 1, 1970. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Paris et al. 2004, pp. 89–91.

- "Riverside Church Will Give $150,000 a Year to the Poor". The New York Times. March 2, 1970. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Paris et al. 2004, p. 206.