Ray tracing (graphics)

In computer graphics, ray tracing is a rendering technique for generating an image by tracing the path of light as pixels in an image plane and simulating the effects of its encounters with virtual objects. The technique is capable of producing a high degree of visual realism, more so than typical scanline rendering methods, but at a greater computational cost. This makes ray tracing best suited for applications where taking a relatively long time to render can be tolerated, such as in still computer-generated images, and film and television visual effects (VFX), but more poorly suited to real-time applications such as video games, where speed is critical in rendering each frame.

Ray tracing is capable of simulating a variety of optical effects, such as reflection and refraction, scattering, and dispersion phenomena (such as chromatic aberration).

History

The idea of ray tracing comes from as early as 16th century when it was described by Albrecht Dürer, who is credited for its invention.[1] In 1982, Scott Roth used the related term ray casting in the context of computer graphics.

Algorithm overview

Optical ray tracing describes a method for producing visual images constructed in 3D computer graphics environments, with more photorealism than either ray casting or scanline rendering techniques. It works by tracing a path from an imaginary eye through each pixel in a virtual screen, and calculating the color of the object visible through it.

Scenes in ray tracing are described mathematically by a programmer or by a visual artist (typically using intermediary tools). Scenes may also incorporate data from images and models captured by means such as digital photography.

Typically, each ray must be tested for intersection with some subset of all the objects in the scene. Once the nearest object has been identified, the algorithm will estimate the incoming light at the point of intersection, examine the material properties of the object, and combine this information to calculate the final color of the pixel. Certain illumination algorithms and reflective or translucent materials may require more rays to be re-cast into the scene.

It may at first seem counterintuitive or "backward" to send rays away from the camera, rather than into it (as actual light does in reality), but doing so is many orders of magnitude more efficient. Since the overwhelming majority of light rays from a given light source do not make it directly into the viewer's eye, a "forward" simulation could potentially waste a tremendous amount of computation on light paths that are never recorded.

Therefore, the shortcut taken in ray tracing is to presuppose that a given ray intersects the view frame. After either a maximum number of reflections or a ray traveling a certain distance without intersection, the ray ceases to travel and the pixel's value is updated.

Calculate rays for rectangular viewport

On input we have (in calculation we use vector normalization and cross product):

- eye position

- target position

- field of view - for human we can assume

- numbers of square pixels on viewport vertical and horizontal direction

- numbers of actual pixel

- vertical vector which indicates where is up and down, usually (not visible on picture) - roll component which determine viewport rotation around point C (where the axis of rotation is the ET section)

The idea is to find the position of each viewport pixel center which allows us to find the line going from eye through that pixel and finally get the ray described by point and vector (or its normalisation ). First we need to find the coordinates of the bottom left viewport pixel and find the next pixel by making a shift along directions parallel to viewport (vectors i ) multiplied by the size of the pixel. Below we introduce formulas which include distance between the eye and the viewport. However, this value will be reduced during ray normalization (so you might as well accept that and remove it from calculations).

Pre-calculations: let's find and normalise vector and vectors which are parallel to the viewport (all depicted on above picture)

note that viewport center , next we calculate viewport sizes divided by 2 including aspect ratio

and then we calculate next-pixel shifting vectors along directions parallel to viewport (), and left bottom pixel center

Calculations: note and ray so

Above formula was tested in this javascript project (works in browser).

Detailed description of ray tracing computer algorithm and its genesis

What happens in (simplified) nature

In nature, a light source emits a ray of light which travels, eventually, to a surface that interrupts its progress. One can think of this "ray" as a stream of photons traveling along the same path. In a perfect vacuum this ray will be a straight line (ignoring relativistic effects). Any combination of four things might happen with this light ray: absorption, reflection, refraction and fluorescence. A surface may absorb part of the light ray, resulting in a loss of intensity of the reflected and/or refracted light. It might also reflect all or part of the light ray, in one or more directions. If the surface has any transparent or translucent properties, it refracts a portion of the light beam into itself in a different direction while absorbing some (or all) of the spectrum (and possibly altering the color). Less commonly, a surface may absorb some portion of the light and fluorescently re-emit the light at a longer wavelength color in a random direction, though this is rare enough that it can be discounted from most rendering applications. Between absorption, reflection, refraction and fluorescence, all of the incoming light must be accounted for, and no more. A surface cannot, for instance, reflect 66% of an incoming light ray, and refract 50%, since the two would add up to be 116%. From here, the reflected and/or refracted rays may strike other surfaces, where their absorptive, refractive, reflective and fluorescent properties again affect the progress of the incoming rays. Some of these rays travel in such a way that they hit our eye, causing us to see the scene and so contribute to the final rendered image.

Ray casting algorithm

The first ray tracing algorithm used for rendering was presented by Arthur Appel in 1968.[2] This algorithm has since been termed "ray casting". The idea behind ray casting is to trace rays from the eye, one per pixel, and find the closest object blocking the path of that ray. Think of an image as a screen-door, with each square in the screen being a pixel. This is then the object the eye sees through that pixel. Using the material properties and the effect of the lights in the scene, this algorithm can determine the shading of this object. The simplifying assumption is made that if a surface faces a light, the light will reach that surface and not be blocked or in shadow. The shading of the surface is computed using traditional 3D computer graphics shading models. One important advantage ray casting offered over older scanline algorithms was its ability to easily deal with non-planar surfaces and solids, such as cones and spheres. If a mathematical surface can be intersected by a ray, it can be rendered using ray casting. Elaborate objects can be created by using solid modeling techniques and easily rendered.

Recursive ray tracing algorithm

The next important research breakthrough came from Turner Whitted in 1979.[3] Previous algorithms traced rays from the eye into the scene until they hit an object, but determined the ray color without recursively tracing more rays. Whitted continued the process. When a ray hits a surface, it can generate up to three new types of rays: reflection, refraction, and shadow.[4] A reflection ray is traced in the mirror-reflection direction. The closest object it intersects is what will be seen in the reflection. Refraction rays traveling through transparent material work similarly, with the addition that a refractive ray could be entering or exiting a material. A shadow ray is traced toward each light. If any opaque object is found between the surface and the light, the surface is in shadow and the light does not illuminate it. This recursive ray tracing added more realism to ray traced images.

Advantages over other rendering methods

Ray tracing-based rendering's popularity stems from its basis in a realistic simulation of light transport, as compared to other rendering methods, such as rasterization, which focuses more on the realistic simulation of geometry. Effects such as reflections and shadows, which are difficult to simulate using other algorithms, are a natural result of the ray tracing algorithm. The computational independence of each ray makes ray tracing amenable to a basic level of parallelization,[5][6] but the divergence of ray paths makes high utilization under parallelism quite difficult to achieve in practice.[7]

Disadvantages

A serious disadvantage of ray tracing is performance (though it can in theory be faster than traditional scanline rendering depending on scene complexity vs. number of pixels on-screen). Until the late 2010s, ray tracing in real time was usually considered impossible on consumer hardware for nontrivial tasks. Scanline algorithms and other algorithms use data coherence to share computations between pixels, while ray tracing normally starts the process anew, treating each eye ray separately. However, this separation offers other advantages, such as the ability to shoot more rays as needed to perform spatial anti-aliasing and improve image quality where needed.

Although it does handle interreflection and optical effects such as refraction accurately, traditional ray tracing is also not necessarily photorealistic. True photorealism occurs when the rendering equation is closely approximated or fully implemented. Implementing the rendering equation gives true photorealism, as the equation describes every physical effect of light flow. However, this is usually infeasible given the computing resources required.

The realism of all rendering methods can be evaluated as an approximation to the equation. Ray tracing, if it is limited to Whitted's algorithm, is not necessarily the most realistic. Methods that trace rays, but include additional techniques (photon mapping, path tracing), give a far more accurate simulation of real-world lighting.

Reversed direction of traversal of scene by the rays

The process of shooting rays from the eye to the light source to render an image is sometimes called backwards ray tracing, since it is the opposite direction photons actually travel. However, there is confusion with this terminology. Early ray tracing was always done from the eye, and early researchers such as James Arvo used the term backwards ray tracing to mean shooting rays from the lights and gathering the results. Therefore, it is clearer to distinguish eye-based versus light-based ray tracing.

While the direct illumination is generally best sampled using eye-based ray tracing, certain indirect effects can benefit from rays generated from the lights. Caustics are bright patterns caused by the focusing of light off a wide reflective region onto a narrow area of (near-)diffuse surface. An algorithm that casts rays directly from lights onto reflective objects, tracing their paths to the eye, will better sample this phenomenon. This integration of eye-based and light-based rays is often expressed as bidirectional path tracing, in which paths are traced from both the eye and lights, and the paths subsequently joined by a connecting ray after some length.[8][9]

Photon mapping is another method that uses both light-based and eye-based ray tracing; in an initial pass, energetic photons are traced along rays from the light source so as to compute an estimate of radiant flux as a function of 3-dimensional space (the eponymous photon map itself). In a subsequent pass, rays are traced from the eye into the scene to determine the visible surfaces, and the photon map is used to estimate the illumination at the visible surface points.[10][11] The advantage of photon mapping versus bidirectional path tracing is the ability to achieve significant reuse of photons, reducing computation, at the cost of statistical bias.

An additional problem occurs when light must pass through a very narrow aperture to illuminate the scene (consider a darkened room, with a door slightly ajar leading to a brightly lit room), or a scene in which most points do not have direct line-of-sight to any light source (such as with ceiling-directed light fixtures or torchieres). In such cases, only a very small subset of paths will transport energy; Metropolis light transport is a method which begins with a random search of the path space, and when energetic paths are found, reuses this information by exploring the nearby space of rays.[12]

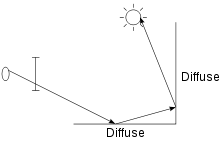

To the right is an image showing a simple example of a path of rays recursively generated from the camera (or eye) to the light source using the above algorithm. A diffuse surface reflects light in all directions.

First, a ray is created at an eyepoint and traced through a pixel and into the scene, where it hits a diffuse surface. From that surface the algorithm recursively generates a reflection ray, which is traced through the scene, where it hits another diffuse surface. Finally, another reflection ray is generated and traced through the scene, where it hits the light source and is absorbed. The color of the pixel now depends on the colors of the first and second diffuse surface and the color of the light emitted from the light source. For example, if the light source emitted white light and the two diffuse surfaces were blue, then the resulting color of the pixel is blue.

Example

As a demonstration of the principles involved in ray tracing, consider how one would find the intersection between a ray and a sphere. This is merely the math behind the line–sphere intersection and the subsequent determination of the colour of the pixel being calculated. There is, of course, far more to the general process of ray tracing, but this demonstrates an example of the algorithms used.

In vector notation, the equation of a sphere with center and radius is

Any point on a ray starting from point with direction (here is a unit vector) can be written as

where is its distance between and . In our problem, we know , , (e.g. the position of a light source) and , and we need to find . Therefore, we substitute for :

Let for simplicity; then

Knowing that d is a unit vector allows us this minor simplification:

This quadratic equation has solutions

The two values of found by solving this equation are the two ones such that are the points where the ray intersects the sphere.

Any value which is negative does not lie on the ray, but rather in the opposite half-line (i.e. the one starting from with opposite direction).

If the quantity under the square root ( the discriminant ) is negative, then the ray does not intersect the sphere.

Let us suppose now that there is at least a positive solution, and let be the minimal one. In addition, let us suppose that the sphere is the nearest object on our scene intersecting our ray, and that it is made of a reflective material. We need to find in which direction the light ray is reflected. The laws of reflection state that the angle of reflection is equal and opposite to the angle of incidence between the incident ray and the normal to the sphere.

The normal to the sphere is simply

where is the intersection point found before. The reflection direction can be found by a reflection of with respect to , that is

Thus the reflected ray has equation

Now we only need to compute the intersection of the latter ray with our field of view, to get the pixel which our reflected light ray will hit. Lastly, this pixel is set to an appropriate color, taking into account how the color of the original light source and the one of the sphere are combined by the reflection.

Adaptive depth control

Adaptive depth control means that the renderer stops generating reflected/transmitted rays when the computed intensity becomes less than a certain threshold. There must always be a set maximum depth or else the program would generate an infinite number of rays. But it is not always necessary to go to the maximum depth if the surfaces are not highly reflective. To test for this the ray tracer must compute and keep the product of the global and reflection coefficients as the rays are traced.

Example: let Kr = 0.5 for a set of surfaces. Then from the first surface the maximum contribution is 0.5, for the reflection from the second: 0.5 × 0.5 = 0.25, the third: 0.25 × 0.5 = 0.125, the fourth: 0.125 × 0.5 = 0.0625, the fifth: 0.0625 × 0.5 = 0.03125, etc. In addition we might implement a distance attenuation factor such as 1/D2, which would also decrease the intensity contribution.

For a transmitted ray we could do something similar but in that case the distance traveled through the object would cause even faster intensity decrease. As an example of this, Hall & Greenberg found that even for a very reflective scene, using this with a maximum depth of 15 resulted in an average ray tree depth of 1.7.[13]

Bounding volumes

We enclose groups of objects in sets of hierarchical bounding volumes and first test for intersection with the bounding volume, and then only if there is an intersection, against the objects enclosed by the volume.

Bounding volumes should be easy to test for intersection, for example a sphere or box (slab). The best bounding volume will be determined by the shape of the underlying object or objects. For example, if the objects are long and thin then a sphere will enclose mainly empty space and a box is much better. Boxes are also easier for hierarchical bounding volumes.

Note that using a hierarchical system like this (assuming it is done carefully) changes the intersection computational time from a linear dependence on the number of objects to something between linear and a logarithmic dependence. This is because, for a perfect case, each intersection test would divide the possibilities by two, and we would have a binary tree type structure. Spatial subdivision methods, discussed below, try to achieve this.

Kay & Kajiya give a list of desired properties for hierarchical bounding volumes:

- Subtrees should contain objects that are near each other and the further down the tree the closer should be the objects.

- The volume of each node should be minimal.

- The sum of the volumes of all bounding volumes should be minimal.

- Greater attention should be placed on the nodes near the root since pruning a branch near the root will remove more potential objects than one farther down the tree.

- The time spent constructing the hierarchy should be much less than the time saved by using it.

Interactive ray tracing

The first implementation of an interactive ray tracer was the LINKS-1 Computer Graphics System built in 1982 at Osaka University's School of Engineering, by professors Ohmura Kouichi, Shirakawa Isao and Kawata Toru with 50 students. It was a massively parallel processing computer system with 514 microprocessors (257 Zilog Z8001's and 257 iAPX 86's), used for rendering realistic 3D computer graphics with high-speed ray tracing. According to the Information Processing Society of Japan: "The core of 3D image rendering is calculating the luminance of each pixel making up a rendered surface from the given viewpoint, light source, and object position. The LINKS-1 system was developed to realize an image rendering methodology in which each pixel could be parallel processed independently using ray tracing. By developing a new software methodology specifically for high-speed image rendering, LINKS-1 was able to rapidly render highly realistic images." It was used to create an early 3D planetarium-like video of the heavens made completely with computer graphics. The video was presented at the Fujitsu pavilion at the 1985 International Exposition in Tsukuba."[14] It was the second system to do so after the Evans & Sutherland Digistar in 1982. The LINKS-1 was reported to be the world's most powerful computer in 1984.[15]

The earliest public record of "real-time" ray tracing with interactive rendering (i.e., updates greater than a frame per second) was credited at the 2005 SIGGRAPH computer graphics conference as being the REMRT/RT tools developed in 1986 by Mike Muuss for the BRL-CAD solid modeling system. Initially published in 1987 at USENIX, the BRL-CAD ray tracer was an early implementation of a parallel network distributed ray tracing system that achieved several frames per second in rendering performance.[16] This performance was attained by means of the highly optimized yet platform independent LIBRT ray tracing engine in BRL-CAD and by using solid implicit CSG geometry on several shared memory parallel machines over a commodity network. BRL-CAD's ray tracer, including the REMRT/RT tools, continue to be available and developed today as open source software.[17]

Since then, there have been considerable efforts and research towards implementing ray tracing at real-time speeds for a variety of purposes on stand-alone desktop configurations. These purposes include interactive 3D graphics applications such as demoscene productions, computer and video games, and image rendering. Some real-time software 3D engines based on ray tracing have been developed by hobbyist demo programmers since the late 1990s.[18]

In 1999 a team from the University of Utah, led by Steven Parker, demonstrated interactive ray tracing live at the 1999 Symposium on Interactive 3D Graphics. They rendered a 35 million sphere model at 512 by 512 pixel resolution, running at approximately 15 frames per second on 60 CPUs.[19]

The OpenRT project included a highly optimized software core for ray tracing along with an OpenGL-like API in order to offer an alternative to the current rasterisation based approach for interactive 3D graphics. Ray tracing hardware, such as the experimental Ray Processing Unit developed by Sven Woop at the Saarland University, has been designed to accelerate some of the computationally intensive operations of ray tracing. On March 16, 2007, the University of Saarland revealed an implementation of a high-performance ray tracing engine that allowed computer games to be rendered via ray tracing without intensive resource usage.[20]

On June 12, 2008 Intel demonstrated a special version of Enemy Territory: Quake Wars, titled Quake Wars: Ray Traced, using ray tracing for rendering, running in basic HD (720p) resolution. ETQW operated at 14–29 frames per second. The demonstration ran on a 16-core (4 socket, 4 core) Xeon Tigerton system running at 2.93 GHz.[21]

At SIGGRAPH 2009, Nvidia announced OptiX, a free API for real-time ray tracing on Nvidia GPUs. The API exposes seven programmable entry points within the ray tracing pipeline, allowing for custom cameras, ray-primitive intersections, shaders, shadowing, etc. This flexibility enables bidirectional path tracing, Metropolis light transport, and many other rendering algorithms that cannot be implemented with tail recursion.[22] OptiX-based renderers are used in Autodesk Arnold, Adobe AfterEffects, Bunkspeed Shot, Autodesk Maya, 3ds max, and many other renderers.

Imagination Technologies offers a free API called OpenRL which accelerates tail recursive ray tracing-based rendering algorithms and, together with their proprietary ray tracing hardware, works with Autodesk Maya to provide what 3D World calls "real-time raytracing to the everyday artist".[23]

In 2014, a demo of the PlayStation 4 video game The Tomorrow Children, developed by Q-Games and SIE Japan Studio, demonstrated new lighting techniques developed by Q-Games, notably cascaded voxel cone ray tracing, which simulates lighting in real-time and uses more realistic reflections rather than screen space reflections.[24]

Nvidia offers hardware-accelerated ray tracing in their GeForce RTX and Quadro RTX GPUs, currently based on the Turing architecture. The Nvidia hardware uses a separate functional block, publicly called an "RT core". This unit is somewhat comparable to a texture unit in size, latency, and interface to the processor core. The unit features BVH traversal, compressed BVH node decompression, ray-AABB intersection testing, and ray-triangle intersection testing.

AMD offers interactive ray tracing on top of OpenCL on Vega graphics cards through Radeon ProRender.[25] The company is reportedly planning to release the second generation Navi GPUs with hardware-accelerated ray tracing in 2020.[26]

The next generation consoles such as the PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X will support dedicated ray tracing hardware components in their GPUs for real-time ray tracing effects.[27][28][29]

Computational complexity

Various complexity results have been proven for certain formulations of the ray tracing problem. In particular, if the decision version of the ray tracing problem is defined as follows[30] – given a light ray's initial position and direction and some fixed point, does the ray eventually reach that point, then the referenced paper proves the following results:

- Ray tracing in 3D optical systems with a finite set of reflective or refractive objects represented by a system of rational quadratic inequalities is undecidable.

- Ray tracing in 3D optical systems with a finite set of refractive objects represented by a system of rational linear inequalities is undecidable.

- Ray tracing in 3D optical systems with a finite set of rectangular reflective or refractive objects is undecidable.

- Ray tracing in 3D optical systems with a finite set of reflective or partially reflective objects represented by a system of linear inequalities, some of which can be irrational is undecidable.

- Ray tracing in 3D optical systems with a finite set of reflective or partially reflective objects represented by a system of rational linear inequalities is PSPACE-hard.

- For any dimension equal to or greater than 2, ray tracing with a finite set of parallel and perpendicular reflective surfaces represented by rational linear inequalities is in PSPACE.

See also

- Beam tracing

- Cone tracing

- Distributed ray tracing

- Global illumination

- Gouraud shading

- List of ray tracing software

- Parallel computing

- Path tracing

- Phong shading

- Progressive refinement

- Shading

- Specular reflection

References

- Georg Rainer Hofmann (1990). "Who invented ray tracing?". The Visual Computer. 6 (3): 120–124. doi:10.1007/BF01911003..

- Appel A. (1968) Some techniques for shading machine renderings of solids. AFIPS Conference Proc. 32 pp.37-45

- Whitted T. (1979) An improved illumination model for shaded display. Proceedings of the 6th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques

- Tomas Nikodym (June 2010). "Ray Tracing Algorithm For Interactive Applications" (PDF). Czech Technical University, FEE.

- J.-C. Nebel. A New Parallel Algorithm Provided by a Computation Time Model, Eurographics Workshop on Parallel Graphics and Visualisation, 24–25 September 1998, Rennes, France.

- A. Chalmers, T. Davis, and E. Reinhard. Practical parallel rendering, ISBN 1-56881-179-9. AK Peters, Ltd., 2002.

- Aila, Timo and Samulii Laine, Understanding the Efficiency of Ray Traversal on GPUs, High Performance Graphics 2009, New Orleans, LA.

- Eric P. Lafortune and Yves D. Willems (December 1993). "Bi-Directional Path Tracing". Proceedings of Compugraphics '93: 145–153.

- Péter Dornbach. "Implementation of bidirectional ray tracing algorithm". Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- Global Illumination using Photon Maps Archived 2008-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Photon Mapping - Zack Waters

- http://graphics.stanford.edu/papers/metro/metro.pdf

- Hall, Roy A.; Greenberg, Donald P. (November 1983). "A Testbed for Realistic Image Synthesis". IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications. 3 (8): 10–20. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.131.1958. doi:10.1109/MCG.1983.263292.

- "【Osaka University 】 LINKS-1 Computer Graphics System". IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- Defanti, Thomas A. (1984). Advances in computers. Volume 23 (PDF). Academic Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-12-012123-9.

- See Proceedings of 4th Computer Graphics Workshop, Cambridge, MA, USA, October 1987. Usenix Association, 1987. pp 86–98.

- "About BRL-CAD". Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- Piero Foscari. "The Realtime Raytracing Realm". ACM Transactions on Graphics. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- Parker, Steven; Martin, William (April 26, 1999). "Interactive ray tracing". I3D '99 Proceedings of the 1999 Symposium on Interactive 3D Graphics (April 1999): 119–126. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.6.8426. doi:10.1145/300523.300537. ISBN 1581130821. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Mark Ward (March 16, 2007). "Rays light up life-like graphics". BBC News. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- Theo Valich (June 12, 2008). "Intel converts ET: Quake Wars to ray tracing". TG Daily. Retrieved June 16, 2008.

- Nvidia (October 18, 2009). "Nvidia OptiX". Nvidia. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- "3DWorld: Hardware review: Caustic Series2 R2500 ray-tracing accelerator card". Retrieved April 23, 2013.3D World, April 2013

- Cuthbert, Dylan (October 24, 2015). "Creating the beautiful, ground-breaking visuals of The Tomorrow Children on PS4". PlayStation Blog. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- GPUOpen Real-time Ray-tracing

- James, Dave (June 11, 2019). "AMD's second-gen RDNA GPUs will feature hardware-accelerated ray tracing in 2020". PCGamesN. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- Warren, Tom (June 8, 2019). "Microsoft hints at next-generation Xbox 'Scarlet' in E3 teasers". The Verge. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Chaim, Gartenberg (October 8, 2019). "Sony confirms PlayStation 5 name, holiday 2020 release date". The Verge. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Warren, Tom (February 24, 2020). "Microsoft reveals more Xbox Series X specs, confirms 12 teraflops GPU". The Verge. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- "Computability and Complexity of Ray Tracing". https://www.cs.duke.edu/~reif/paper/tygar/raytracing.pdf