Politics of Germany

Germany is a democratic, federal parliamentary republic, where federal legislative power is vested in the Bundestag (the parliament of Germany) and the Bundesrat (the representative body of the Länder, Germany's regional states).

| |

| Polity type | Federal democratic parliamentary republic |

|---|---|

| Constitution | Basic Law for Germany |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | Bundestag and Bundesrat |

| Type | Bicameral |

| Meeting place | Reichstag building |

| Presiding officer | Wolfgang Schäuble, President of the Bundestag |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | Federal President |

| Currently | Frank-Walter Steinmeier |

| Appointer | Bundesversammlung |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Federal Chancellor |

| Currently | Angela Merkel |

| Appointer | President |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Cabinet of Germany |

| Current cabinet | Cabinet Merkel IV |

| Leader | Chancellor |

| Deputy leader | Vice Chancellor |

| Appointer | President |

| Headquarters | Chancellery |

| Ministries | 15 |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | Judiciary of Germany |

| Federal Constitutional Court | |

| Chief judge | Andreas Voßkuhle |

| Seat | Seat of the Court, Karlsruhe |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Germany |

|

|

|

|

Head of State

|

|

Executive

|

|

Legislature

|

|

Judiciary

|

|

Administrative divisions

|

|

Elections

|

|

Foreign relations

|

|

The multilateral system has, since 1949, been dominated by the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). The judiciary of Germany is independent of the executive and the legislature, while it is common for leading members of the executive to be members of the legislature as well. The political system is laid out in the 1949 constitution, the Grundgesetz (Basic Law), which remained in effect with minor amendments after German reunification in 1990.

The constitution emphasizes the protection of individual liberty in an extensive catalogue of human and civil rights and divides powers both between the federal and state levels and between the legislative, executive and judicial branches.

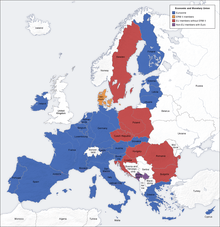

West Germany was a founding member of the European Community in 1958, which became the EU in 1993. It is part of the Schengen Area, and has been a member of the eurozone since 1999. It is a member of the United Nations, NATO, the G7, the G20 and the OECD.

The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Germany a "full democracy" in 2019.[1]

History

Prior to 1998

After 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany had Christian Democratic chancellors for 20 years until a coalition between the Social Democrats and the Liberals took over. From 1982, Christian Democratic leader Helmut Kohl was chancellor in a coalition with the Liberals for 16 years. In this period fell the reunification of Germany, in 1990: the German Democratic Republic joined the Federal Republic. In the former GDR's territory, five Länder (states) were established or reestablished. The two parts of Berlin united as one "Land" (state).

The political system of the Federal Republic remained more or less unchanged. Specific provisions for the former GDR territory were enabled via the unification treaty between the Federal Republic and the GDR prior to the unification day of 3 October 1990. However, Germany saw in the following two distinct party systems: the Green party and the Liberals remained mostly West German parties, while in the East the former socialist state party, now called PDS, flourished along with the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats.

1998–2005

After 16 years of the Christian–Liberal coalition, led by Helmut Kohl, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) together with the Greens won the Bundestag elections of 1998. SPD vice chairman Gerhard Schröder positioned himself as a centrist candidate, in contradiction to the leftist SPD chairman Oskar Lafontaine. The Kohl government was hurt at the polls by slower economic growth in the East in the previous two years, and constantly high unemployment. The final margin of victory was sufficiently high to permit a "red-green" coalition of the SPD with Alliance 90/The Greens (Bündnis '90/Die Grünen), bringing the Greens into a national government for the first time.

Initial problems of the new government, marked by policy disputes between the moderate and traditional left wings of the SPD, resulted in some voter disaffection. Lafontaine left the government (and later his party) in early 1999. The CDU won in some important state elections but was hit in 2000 by a party donation scandal from the Kohl years. As a result of this Christian Democratic Union (CDU) crisis, Angela Merkel became chair.

The next election for the Bundestag was on 22 September 2002. Gerhard Schröder led the coalition of SPD and Greens to an eleven-seat victory over the Christian Democrat challengers headed by Edmund Stoiber (CSU). Three factors are generally cited that enabled Schröder to win the elections despite poor approval ratings a few months before and a weaker economy: good handling of the 100-year flood, firm opposition to the US 2003 invasion of Iraq, and Stoiber's unpopularity in the east, which cost the CDU crucial seats there.

In its second term, the red–green coalition lost several very important state elections, for example in Lower Saxony where Schröder was the prime minister from 1990 to 1998. On 20 April 2003, chancellor Schröder announced massive labor market reforms, called Agenda 2010, that cut unemployment benefits. Although these reforms sparked massive protests, they are now credited with being in part responsible for the relatively strong economic performance of Germany during the euro-crisis and the decrease in unemployment in Germany in the years 2006-2007.[2]

2005–2009

.jpg)

On 22 May 2005 the SPD received a devastating defeat in its former heartland, North Rhine-Westphalia. Half an hour after the election results, the SPD chairman Franz Müntefering announced that the chancellor would clear the way for new federal elections.

This took the republic by surprise, especially because the SPD was below 20% in polls at the time. The CDU quickly announced Angela Merkel as Christian Democrat candidate for chancellor, aspiring to be the first female chancellor in German history.

New for the 2005 election was the alliance between the newly formed Electoral Alternative for Labor and Social Justice (WASG) and the PDS, planning to fuse into a common party (see Left Party.PDS). With the former SPD chairman, Oskar Lafontaine for the WASG and Gregor Gysi for the PDS as prominent figures, this alliance soon found interest in the media and in the population. Polls in July saw them as high as 12%.

Whereas in May and June 2005 victory of the Christian Democrats seemed highly likely, with some polls giving them an absolute majority, this picture changed shortly before the election on 18 September 2005.

The election results of 18 September were surprising because they differed widely from the polls of the previous weeks. The Christian Democrats even lost votes compared to 2002, narrowly reaching the first place with only 35.2%, and failed to get a majority for a "black–yellow" government of CDU/CSU and liberal FDP. But the red–green coalition also failed to get a majority, with the SPD losing votes, but polling 34.2% and the greens staying at 8.1%. The Left reached 8.7% and entered the Bundestag, whereas the far-right NPD only got 1.6%.[3]

The most likely outcome of coalition talks was a so-called grand coalition between the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democrats (SPD). Three party coalitions and coalitions involving The Left had been ruled out by all interested parties (including The Left itself). On 22 November 2005, Angela Merkel was sworn in by president Horst Köhler for the office of Bundeskanzlerin.

The existence of the grand coalition on federal level helped smaller parties' electoral prospects in state elections. Since in 2008, the CSU lost its absolute majority in Bavaria and formed a coalition with the FDP, the grand coalition had no majority in the Bundesrat and depended on FDP votes on important issues. In November 2008, the SPD re-elected its already retired chair Franz Müntefering and made Frank-Walter Steinmeier its leading candidate for the federal election in September 2009.

As a result of that federal election, the grand coalition brought losses for both parties and came to an end. The SPD suffered the heaviest losses in its history and was unable to form a coalition government. The CDU/CSU had only little losses but also reached a new historic low with its worst result since 1949. The three smaller parties thus had more seats in the German Bundestag than ever before, with the liberal party FDP winning 14.6% of votes.

2009–2013

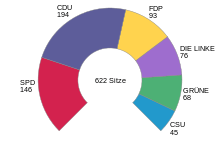

The CDU/CSU and FDP together held 332 seats (of 622 total seats) and had been in coalition since 27 October 2009. Angela Merkel was re-elected as chancellor, and Guido Westerwelle served as the foreign minister and vice chancellor of Germany. After being elected into the federal government, the FDP suffered heavy losses in the following state elections. The FDP had promised to lower taxes in the electoral campaign, but after being part of the coalition they had to concede that this was not possible due to the economic crisis of 2008. Because of the losses, Guido Westerwelle had to resign as chair of the FDP in favor of Philipp Rösler, Federal minister of health, who was consequently appointed as vice chancellor. Shortly after, Philipp Rösler changed office and became federal minister of economics and technology.

After their electoral fall, the Social Democrats were led by Sigmar Gabriel, a former federal minister and prime minister of Lower Saxony, and by Frank-Walter Steinmeier as the head of the parliamentary group. He resigned on 16 January 2017 and proposed his longtime friend and president of European Parliament Martin Schulz as his successor and chancellor candidate.[4] Germany has seen increased political activity by citizens outside the established political parties with respect to local and environmental issues such as the location of Stuttgart 21, a railway hub, and construction of Berlin Brandenburg Airport.[5]

2013–2017

Bundestag after 2013 elections

The 18th federal elections in Germany resulted in the re-election of Angela Merkel and her Christian democratic parliamentary group of the parties CDU and CSU, receiving 41.5% of all votes. Following Merkel's first two historically low results, her third campaign marked the CDU/CSU's best result since 1994 and only for the second time in German history the possibility of gaining an absolute majority. Their former coalition partner, the FDP, narrowly failed to reach the 5% threshold and did not gain seats in the Bundestag.[6]

Not having reached an absolute majority, the CDU/CSU formed a grand coalition with the social-democratic SPD after the longest coalition talks in history, making the head of the party Sigmar Gabriel vice-chancellor and federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy. Together they held 504 of a total 631 seats (CDU/CSU 311 and SPD 193). The only two opposition parties were The Left (64 seats) and Alliance '90/The Greens (63 seats), which was acknowledged as creating a critical situation in which the opposition parties did not even have enough seats to use the special controlling powers of the opposition.[7]

Since 2017

.svg.png)

The 19th federal elections in Germany took place on 24 September 2017. The two big parties, the conservative parliamentary group CDU/CSU and the social democrat SPD were in a similar situation as in 2009, after the last grand coalition had ended, and both had suffered severe losses; reaching their second worst and worst result respectively in 2017.

Many votes in the 2017 elections went to smaller parties, leading the right-wing populist party AfD (Alternative for Germany) into the Bundestag which marked a big shift in German politics since it was the first far-right party to win seats in parliament since the 1950s.

With Merkel's candidacy for a fourth term, the CDU/CSU only reached 33.0% of the votes, but won the highest number of seats, leaving no realistic coalition option without the CDU/CSU. As all parties in the Bundestag strictly ruled out a coalition with the AfD, the only options for a majority coalition were a so-called "Jamaican" coalition (CDU/CSU, FDP, Greens; named after the party colors resembling those of the Jamaican flag) and a grand coalition with the SPD, which was at first opposed by the Social Democrats and their leader Martin Schulz.

Coalition talks between the three parties of the "Jamaican" coalition were held but the final proposal was rejected by the liberals of the FDP, leaving the government in limbo.[8][9] Following the unprecedented situation, for the first time in German history different minority coalitions or even direct snap coalitions were also heavily discussed. At this point, Federal President Steinmeier invited leaders of all parties for talks about a government, being the first President in the history of the Federal Republic to do so.

Official coalition talks between CDU/CSU and SPD started in January 2018 and led to a renewal of the grand coalition on 12 March 2018 as well as the subsequent re-election of Angela Merkel as chancellor.[10]

Constitution

The "Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany" (Grundgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland) is the Constitution of Germany.[11] It was formally approved on 8 May 1949, and, with the signature of the Allies of World War II on 12 May, came into effect on 23 May, as the constitution of those states of West Germany that were initially included within the Federal Republic. The 1949 Basic Law is a response to the perceived flaws of the 1919 Weimar Constitution, which failed to prevent the rise of the Nazi party in 1933. Since 1990, in the course of the reunification process after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Basic Law also applies to the eastern states of the former German Democratic Republic.

Executive

Head of state

.jpg)

The German head of state is the Federal President. As in Germany's parliamentary system of government, the Federal Chancellor runs the government and day-to-day politics, the role of the Federal President is mostly ceremonial. The Federal President, by their actions and public appearances, represents the state itself, its existence, its legitimacy, and unity. Their office involves an integrative role.[12] Nearly all actions of the Federal President become valid only after a countersignature of a government member.

The President is not obliged by Constitution to refrain from political views. He or she is expected to give direction to general political and societal debates, but not in a way that links him to party politics. Most German Presidents were active politicians and party members prior to the office, which means that they have to change their political style when becoming President. The function comprises the official residence of Bellevue Palace.

Under Article 59 (1) of the Basic Law, the Federal President represents the Federal Republic of Germany in matters of international law, concludes treaties with foreign states on its behalf and accredits diplomats.[13]

All federal laws must be signed by the President before they can come into effect; he or she does not have a veto, but the conditions for refusing to sign a law on the basis of unconstitutionality are the subject of debate.[14] The office is currently held by Frank-Walter Steinmeier (since 2017).

The Federal President does have a role in the political system, especially at the establishment of a new government and the dissolution of the Bundestag (parliament). This role is usually nominal but can become significant in case of political instability. Additionally, a Federal President together with the Federal Council can support the government in a "legislatory emergency state" to enable laws against the will of the Bundestag (Article 81 of the Basic Law). However, until now the Federal President has never had to use these "reserve powers".

Head of government

The Bundeskanzler (federal chancellor) heads the Bundesregierung (federal government) and thus the executive branch of the federal government. They are elected by and responsible to the Bundestag, Germany's parliament. The other members of the government are the Federal Ministers; they are chosen by the Chancellor. Germany, like the United Kingdom, can thus be classified as a parliamentary system. The office is currently held by Angela Merkel (since 2005).

The Chancellor cannot be removed from office during a four-year term unless the Bundestag has agreed on a successor. This constructive vote of no confidence is intended to avoid a similar situation to that of the Weimar Republic in which the executive did not have enough support in the legislature to govern effectively, but the legislature was too divided to name a successor. The current system also prevents the Chancellor from calling a snap election.

Except in the periods 1969–1972 and 1976–1982, when the Social Democratic party of Chancellor Brandt and Schmidt came in second in the elections, the chancellor has always been the candidate of the largest party, usually supported by a coalition of two parties with a majority in the parliament. The chancellor appoints one of the federal ministers as their deputy,[15] who has the unofficial title Vice Chancellor (German: Vizekanzler). The office is currently held by Olaf Scholz (since March 2018).

Cabinet

The German Cabinet (Bundeskabinett or Bundesregierung) is the chief executive body of the Federal Republic of Germany. It consists of the chancellor and the cabinet ministers. The fundamentals of the cabinet's organization are set down in articles 62–69 of the Basic Law. The current cabinet is Merkel IV (since 2018).

Agencies

Agencies of the German government include:

- Federal Intelligence Service (Bundesnachrichtendienst)

- Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation (Bundesstelle für Flugunfalluntersuchung)

- Federal Aviation Office (Luftfahrt-Bundesamt)

- Federal Bureau for Maritime Casualty Investigation (Bundesstelle für Seeunfalluntersuchung)

- Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (Bundesamt für Seeschifffahrt und Hydrographie)

- Federal Railway Accident Investigation Board (Eisenbahn-Unfalluntersuchungsstelle des Bundes)

- Federal Railway Authority (Eisenbahn-Bundesamt)

Legislature

Federal legislative power is divided between the Bundestag and the Bundesrat. The Bundestag is directly elected by the German people, while the Bundesrat represents the governments of the regional states (Länder). The federal legislature has powers of exclusive jurisdiction and concurrent jurisdiction with the states in areas specified in the constitution.

The Bundestag is more powerful than the Bundesrat and only needs the latter's consent for proposed legislation related to revenue shared by the federal and state governments, and the imposition of responsibilities on the states. In practice, however, the agreement of the Bundesrat in the legislative process is often required, since federal legislation frequently has to be executed by state or local agencies. In the event of disagreement between the Bundestag and the Bundesrat, either side can appeal to the Vermittlungsausschuss to find a compromise.

Bundestag

The Bundestag (Federal Diet) is elected for a four-year term and consists of 598 or more members elected by a means of mixed-member proportional representation, which Germans call "personalised proportional representation". 299 members represent single-seat constituencies and are elected by a first past the post electoral system. Parties that obtain fewer constituency seats than their national share of the vote are allotted seats from party lists to make up the difference. In contrast, parties that obtain more constituency seats than their national share of the vote are allowed to keep these so-called overhang seats. In the parliament that was elected in 2009, there were 24 overhang seats, giving the Bundestag a total of 622 members. After Bundestag elections since 2013, other parties obtain extra seats ("balance seats") that offset advantages from their rival's overhang seats. The current Bundestag is the largest in German history with 709 members.

A party must receive either five percent of the national vote or win at least three directly elected seats to be eligible for non-constituency seats in the Bundestag. This rule, often called the "five percent hurdle", was incorporated into Germany's election law to prevent political fragmentation and disproportionately influential minority parties. The first Bundestag elections were held in the Federal Republic of Germany ("West Germany") on 14 August 1949. Following reunification, elections for the first all-German Bundestag were held on 2 December 1990. The last federal election was held on 24 September 2017.

Judiciary

Germany follows the civil law tradition. The judicial system comprises three types of courts.

- Ordinary courts, dealing with criminal and most civil cases, are the most numerous by far. The Federal Court of Justice of Germany (Bundesgerichtshof) is the highest ordinary court and also the highest court of appeals.

- Specialized courts hear cases related to administrative, labour, social, fiscal and patent law.

- Constitutional courts focus on judicial review and constitutional interpretation. The Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) is the highest court dealing with constitutional matters.

The main difference between the Federal Constitutional Court and the Federal Court of Justice is that the Federal Constitutional Court may only be called if a constitutional matter within a case is in question (e.g. a possible violation of human rights in a criminal trial), while the Federal Court of Justice may be called in any case.

Foreign relations

Germany maintains a network of 229 diplomatic missions abroad and holds relations with more than 190 countries.[16] It is the largest contributor to the budget of the European Union (providing 27%) and third largest contributor to the United Nations (providing 8%). Germany is a member of the NATO defence alliance, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the G8, the G20, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Germany has played a leading role in the European Union since its inception and has maintained a strong alliance with France since the end of World War II. The alliance was especially close in the late 1980s and early 1990s under the leadership of Christian Democrat Helmut Kohl and Socialist François Mitterrand. Germany is at the forefront of European states seeking to advance the creation of a more unified European political, defence, and security apparatus.[17] For a number of decades after WWII, the Federal Republic of Germany kept a notably low profile in international relations, because of both its recent history and its occupation by foreign powers.[18]

During the Cold War, Germany's partition by the Iron Curtain made it a symbol of East–West tensions and a political battleground in Europe. However, Willy Brandt's Ostpolitik was a key factor in the détente of the 1970s.[19] In 1999, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder's government defined a new basis for German foreign policy by taking a full part in the decisions surrounding the NATO war against Yugoslavia and by sending German troops into combat for the first time since World War II.[20]

The governments of Germany and the United States are close political allies.[21] The 1948 Marshall Plan and strong cultural ties have crafted a strong bond between the two countries, although Schröder's very vocal opposition to the Iraq War had suggested the end of Atlanticism and a relative cooling of German–American relations.[22] The two countries are also economically interdependent: 5.0% of German exports in goods are US-bound and 3.5% of German imported goods originate from the US with a trade deficit of -63,678.5 million dollars for the United States (2017).[23] Other signs of the close ties include the continuing position of German–Americans as the largest reported ethnic group in the US,[24] and the status of Ramstein Air Base (near Kaiserslautern) as the largest US military community outside the US.[25]

The policy on foreign aid is an important area of German foreign policy. It is formulated by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and carried out by the implementing organisations. The German government sees development policy as a joint responsibility of the international community.[26] It is the world's fourth biggest aid donor after the United States, the United Kingdom and France.[27] Germany spent 0.37 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on development, which is below the government's target of increasing aid to 0.51 per cent of GDP by 2010.

Administrative divisions

Germany comprises sixteen states that are collectively referred to as Länder.[28] Due to differences in size and population, the subdivision of these states varies especially between city-states (Stadtstaaten) and states with larger territories (Flächenländer). For regional administrative purposes five states, namely Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia and Saxony, consist of a total of 22 Government Districts (Regierungsbezirke). As of 2009 Germany is divided into 403 districts (Kreise) on municipal level, these consist of 301 rural districts and 102 urban districts.[29]

| State | Capital | Area (km²) | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | Stuttgart | 35,752 | 10,717,000 |

| Bavaria | Munich | 70,549 | 12,444,000 |

| Berlin | Berlin | 892 | 3,400,000 |

| Brandenburg | Potsdam | 29,477 | 2,568,000 |

| Bremen | Bremen | 404 | 663,000 |

| Hamburg | Hamburg | 755 | 1,735,000 |

| Hessen | Wiesbaden | 21,115 | 6,098,000 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | Schwerin | 23,174 | 1,720,000 |

| Lower Saxony | Hanover | 47,618 | 8,001,000 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | Düsseldorf | 34,043 | 18,075,000 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | Mainz | 19,847 | 4,061,000 |

| Saarland | Saarbrücken | 2,569 | 1,056,000 |

| Saxony | Dresden | 18,416 | 4,296,000 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | Magdeburg | 20,445 | 2,494,000 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | Kiel | 15,763 | 2,829,000 |

| Thuringia | Erfurt | 16,172 | 2,355,000 |

See also

- Federalism in Germany

- List of political parties in Germany

- List of Federal Republic of Germany governments

- Party finance in Germany

- Political culture of Germany

References

- The Economist Intelligence Unit (8 January 2019). "Democracy Index 2019". Economist Intelligence Unit. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Arbeitslose und Arbeitslosenquote

- Official election results Archived 23 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Sigmar Gabriel resigns as Social Democratic Party leader and chancellor candidate - World Socialist Web Site". Wsws.org. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Dempsey, Judy (1 May 2011). "German Politics Faces Grass-Roots Threat". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Germany's Left Turn". The Times. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Wearden, Graeme (20 November 2017). "Markets rattled as German coalition talks collapse – business live". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- Henley, Jon (24 September 2017). "German elections 2017: Angela Merkel wins fourth term but AfD makes gains – as it happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- "Union und SPD unterschreiben Koalitionsvertrag". Zeit.de. 12 March 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Deutscher Bundestag - Grundgesetz" (in German). Bundestag.de. 25 September 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Website of the Federal President of Germany Retrieved 13 April 2014

- Website of the Federal President of Germany Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Lange, Friederike Valerie (2010). Grundrechtsbindung des Gesetzgebers: eine rechtsvergleichende Studie zu Deutschland, Frankreich und den USA (in German). Mohr Siebeck. pp. 123ff. ISBN 978-316-150420-4.

- Article 69 of the Basic Law

- German Missions Abroad German Federal Foreign Office. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- Declaration by the Franco-German Defence and Security Council Archived 25 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine Elysee.fr 13 May 3004. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Glaab, Manuela. German Foreign Policy: Book Review Internationale Politik. Spring 2003. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- Harrison, Hope. "The Berlin Wall, Ostpolitik and Détente" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2012. (91.1 KB) German historical institute, Washington, DC, Bulletin supplement 1, 2004, American détente and German ostpolitik, 1969–1972".

- Germany's New Face Abroad Deutsche Welle. 14 October 2005. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Background Note: Germany U.S. Department of State. 6 July 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Ready for a Bush hug?, The Economist, 6 July 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- "Foreign Trade - U.S. Trade in Goods with Germany". Website of the United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- German Still Most Frequently Reported Ancestry Archived 5 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Census Bureau 30 June 2004. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Kaiserslautern, Germany Overview Archived 18 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Military. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Aims of German development policy Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development 10 April 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- Table: Net Official Development Assistance 2009 Archived 26 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine OECD

- The individual denomination is either Land [state], Freistaat [free state] or Freie (und) Hansestadt [free (and) Hanseatic city].

"The Federal States". www.bundesrat.de. Bundesrat of Germany. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

"Amtliche Bezeichnung der Bundesländer" [Official denomination of federated states] (PDF; download file "Englisch"). www.auswaertiges-amt.de (in German). Federal Foreign Office. Retrieved 22 October 2011. - "Kreisfreie Städte und Landkreise nach Fläche und Bevölkerung 31 December 2009" (in German). Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland. October 2010. Archived from the original (XLS) on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

_Ostseite.jpg)

.svg.png)