Pelé

Edson Arantes do Nascimento (Brazilian Portuguese: [ˈɛtsõ (w)ɐˈɾɐ̃tʃiz du nɐsiˈmẽtu]; born 23 October 1940), known as Pelé ([peˈlɛ]), is a Brazilian retired professional footballer who played as a forward. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest players of all time. In 1999, he was voted World Player of the Century by the International Federation of Football History & Statistics (IFFHS), and was one of the two joint winners of the FIFA Player of the Century award. That same year, Pelé was elected Athlete of the Century by the International Olympic Committee. According to the IFFHS, Pelé is the most successful domestic league goal-scorer in football history scoring 650 goals in 694 League matches, and in total 1281 goals in 1363 games, which included unofficial friendlies and is a Guinness World Record. During his playing days, Pelé was for a period the best-paid athlete in the world.

Pelé | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pelé in 1995 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Edson Arantes do Nascimento 23 October 1940 Três Corações, Minas Gerais, Brazil | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Partner(s) | Xuxa Meneghel (1981–1986) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Dondinho, Celeste Arantes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | pele10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pelé began playing for Santos at age 15 and the Brazil national team at 16. During his international career, he won three FIFA World Cups: 1958, 1962 and 1970, being the only player ever to do so. Pelé is the all-time leading goalscorer for Brazil with 77 goals in 92 games. At club level he is the record goalscorer for Santos, and led them to the 1962 and 1963 Copa Libertadores. Known for connecting the phrase "The Beautiful Game" with football, Pelé's "electrifying play and penchant for spectacular goals" made him a star around the world, and his teams toured internationally in order to take full advantage of his popularity. Since retiring in 1977, Pelé has been a worldwide ambassador for football and has made many acting and commercial ventures. In 2010, he was named the Honorary President of the New York Cosmos.

Averaging almost a goal per game throughout his career, Pelé was adept at striking the ball with either foot in addition to anticipating his opponents' movements on the field. While predominantly a striker, he could also drop deep and take on a playmaking role, providing assists with his vision and passing ability, and he would also use his dribbling skills to go past opponents. In Brazil, he is hailed as a national hero for his accomplishments in football and for his outspoken support of policies that improve the social conditions of the poor. Throughout his career and in his retirement, Pelé received several individual and team awards for his performance in the field, his record-breaking achievements, and legacy in the sport.

Early years

Pelé was born Edson Arantes do Nascimento on 23 October 1940, in Três Corações, Minas Gerais, Brazil, the son of Fluminense footballer Dondinho (born João Ramos do Nascimento) and Celeste Arantes. He was the elder of two siblings.[1] He was named after the American inventor Thomas Edison.[2] His parents decided to remove the "i" and call him "Edson", but there was a mistake on the birth certificate, leading many documents to show his name as "Edison", not "Edson", as he is called.[2][3] He was originally nicknamed "Dico" by his family.[1][4] He received the nickname "Pelé" during his school days, when it is claimed he was given it because of his pronunciation of the name of his favorite player, local Vasco da Gama goalkeeper Bilé, which he misspoke but the more he complained the more it stuck. In his autobiography, Pelé stated he had no idea what the name means, nor did his old friends.[1] Apart from the assertion that the name is derived from that of Bilé, and that it is Hebrew for "miracle" (פֶּ֫לֶא), the word has no known meaning in Portuguese.[note 1][5]

Pelé grew up in poverty in Bauru in the state of São Paulo. He earned extra money by working in tea shops as a servant. Taught to play by his father, he could not afford a proper football and usually played with either a sock stuffed with newspaper and tied with a string or a grapefruit.[6][1] He played for several amateur teams in his youth, including Sete de Setembro, Canto do Rio, São Paulinho, and Amériquinha.[7] Pelé led Bauru Athletic Club juniors (coached by Waldemar de Brito) to two São Paulo state youth championships.[8] In his mid-teens, he played for an indoor football team called Radium. Indoor football had just become popular in Bauru when Pelé began playing it. He was part of the first Futebol de Salão (indoor football) competition in the region. Pelé and his team won the first championship and several others.[9]

According to Pelé, indoor football presented difficult challenges; he said it was a lot quicker than football on the grass and that players were required to think faster because everyone is close to each other in the pitch. Pelé accredits indoor football for helping him think better on the spot. In addition, indoor football allowed him to play with adults when he was about 14 years old. In one of the tournaments he participated, he was initially considered too young to play, but eventually went on to end up top scorer with fourteen or fifteen goals. "That gave me a lot of confidence", Pelé said, "I knew then not to be afraid of whatever might come".[9]

Club career

Santos

In 1956, de Brito took Pelé to Santos, an industrial and port city located near São Paulo, to try out for professional club Santos FC, telling the directors at Santos that the 15-year-old would be "the greatest football player in the world."[10] Pelé impressed Santos coach Lula during his trial at the Estádio Vila Belmiro, and he signed a professional contract with the club in June 1956.[11] Pelé was highly promoted in the local media as a future superstar. He made his senior team debut on 7 September 1956 at the age of 15 against Corinthians Santo Andre and had an impressive performance in a 7–1 victory, scoring the first goal in his prolific career during the match.[12][13]

When the 1957 season started, Pelé was given a starting place in the first team and, at the age of 16, became the top scorer in the league. Ten months after signing professionally, the teenager was called up to the Brazil national team. After the 1958 and the 1962 World Cup, wealthy European clubs, such as Real Madrid, Juventus and Manchester United,[14] tried to sign him in vain; in 1958 Inter Milan even managed to get him a regular contract, but Angelo Moratti was forced to tear the contract up at the request of Santos' chairman following a revolt by Santos' Brazilian fans.[15] However, in 1961 the government of Brazil under President Jânio Quadros declared Pelé an "official national treasure" to prevent him from being transferred out of the country.[6][16]

Pelé won his first major title with Santos in 1958 as the team won the Campeonato Paulista; Pelé would finish the tournament as top scorer with 58 goals,[17] a record that stands today. A year later, he would help the team earn their first victory in the Torneio Rio-São Paulo with a 3–0 over Vasco da Gama.[18] However, Santos was unable to retain the Paulista title. In 1960, Pelé scored 33 goals to help his team regain the Campeonato Paulista trophy but lost out on the Rio-São Paulo tournament after finishing in 8th place.[19] In the 1960 season, Pelé scored 47 goals and helped Santos regain the Campeonato Paulista. The club went on to win the Taça Brasil that same year, beating Bahia in the finals; Pelé finished as top scorer of the tournament with 9 goals. The victory allowed Santos to participate in the Copa Libertadores, the most prestigious club tournament in the Western hemisphere.[20]

—Benfica goalkeeper Costa Pereira following the loss to Santos in 1962.[21]

Santos's most successful Copa Libertadores season started in 1962;[22] the team was seeded in Group One alongside Cerro Porteño and Deportivo Municipal Bolivia, winning every match of their group but one (a 1–1 away tie versus Cerro). Santos defeated Universidad Católica in the semi-finals and met defending champions Peñarol in the finals. Pelé scored twice in the playoff match to secure the first title for a Brazilian club.[23] Pelé finished as the second top scorer of the competition with four goals. That same year, Santos would successfully defend the Campeonato Brasileiro (with 37 goals from Pelé) and the Taça Brasil (Pelé scoring four goals in the final series against Botafogo). Santos would also win the 1962 Intercontinental Cup against Benfica.[24] Wearing his number 10 shirt, Pelé produced one of the best performances of his career, scoring a hat-trick in Lisbon as Santos won 5–2.[25][26] As the defending champions, Santos qualified automatically to the semi-final stage of the 1963 Copa Libertadores. The ballet blanco, the nickname given to Santos for Pelé, managed to retain the title after victories over Botafogo and Boca Juniors. Pelé helped Santos overcome a Botafogo team that contained Brazilian legends such as Garrincha and Jairzinho with a last-minute goal in the first leg of the semi-finals which made it 1–1. In the second leg, Pelé scored a hat-trick in the Estádio do Maracanã as Santos won, 0–4, in the second leg. Santos started the final series by winning, 3–2, in the first leg and defeating Boca Juniors 1–2, in La Bombonera. It was a rare feat in official competitions, with another goal from Pelé.[27] Santos became the first (and to date the only) Brazilian team to lift the Copa Libertadores in Argentine soil. Pelé finished the tournament with 5 goals. Santos lost the Campeonato Paulista after finishing in third place but went on to win the Rio-São Paulo tournament after a 0–3 win over Flamengo in the final, with Pelé scoring one goal. Pelé would also help Santos retain the Intercontinental Cup and the Taça Brasil against Milan and Bahia respectively.[24]

In the 1964 Copa Libertadores, Santos were beaten in both legs of the semi-finals by Independiente. The club won the Campeonato Paulista, with Pelé netting 34 goals. Santos also shared the Rio-São Paulo title with Botafogo and won the Taça Brasil for the fourth consecutive year. In the 1965 Copa Libertadores, Santos reached the semi-finals and met Peñarol in a rematch of the 1962 final. After two matches, a playoff was needed to break the tie.[28] Unlike 1962, Peñarol came out on top and eliminated Santos 2–1.[28] Pelé would, however, finish as the topscorer of the tournament with eight goals.[29] This proved to be the start of a decline as Santos failed to retain the Torneio Rio-São Paulo. In 1966, Pelé and Santos also failed to retain the Taça Brasil as Pelé's goals were not enough to prevent a 9–4 defeat by Cruzeiro (led by Tostão) in the final series. The club did, however, win the Campeonato Paulista in 1967, 1968 and 1969. On 19 November 1969, Pelé scored his 1000th goal in all competitions, in what was a highly anticipated moment in Brazil. The goal, popularly dubbed O Milésimo (The Thousandth), occurred in a match against Vasco da Gama, when Pelé scored from a penalty kick, at the Maracanã Stadium.[30]

Pelé states that his most memorable goal was scored at Rua Javari stadium on a Campeonato Paulista match against São Paulo rival Clube Atlético Juventus on 2 August 1959. As there is no video footage of this match, Pelé asked that a computer animation be made of this specific goal.[31] In March 1961, Pelé scored the gol de placa (goal worthy of a plaque), against Fluminense at the Maracanã.[32] Pelé received the ball on the edge of his own penalty area, and ran the length of the field, eluding opposition players with feints, before striking the ball beyond the goalkeeper.[32] A plaque was commissioned with a dedication to "the most beautiful goal in the history of the Maracanã".[33]

In 1967, the two factions involved in the Nigerian Civil War agreed to a 48-hour ceasefire so they could watch Pelé play an exhibition game in Lagos.[34] During his time at Santos, Pelé played alongside many gifted players, including Zito, Pepe, and Coutinho; the latter partnered him in numerous one-two plays, attacks, and goals.[35]

New York Cosmos

After the 1974 season (his 19th with Santos), Pelé retired from Brazilian club football although he continued to occasionally play for Santos in official competitive matches. Two years later, he came out of semi-retirement to sign with the New York Cosmos of the North American Soccer League (NASL) for the 1975 season.[36] Though well past his prime at this point, Pelé was credited with significantly increasing public awareness and interest of the sport in the United States.[37] During his first public appearance in Boston, he was injured by a crowd of fans who had surrounded him and was evacuated on a stretcher.[38] Pelé made his debut for the Cosmos on 15 June 1975 against the Dallas Tornado at Downing Stadium, scoring one goal in a 2–2 draw.[39]

In 1975, one week before the Lebanese Civil War, Pelé played a friendly game for the Lebanese club Nejmeh against a team of Lebanese Premier League stars,[40] scoring two goals which were not included in his official tally.[41][42] On the day of the game, 40,000 spectators were at the stadium from early morning to watch the match.[40]

Hoping to fuel the same kind of awareness in the Dominican Republic, he and the Cosmos team played in an exhibition match against Haitian team, Violette AC, in the Santo Domingo Olympic Stadium on 3 June 1976, where over 25,000 fans watched him score a winning goal in the last seconds of the match, leading the Cosmos to a 2–1 victory.[43] He led the Cosmos to the 1977 NASL championship, in his third and final season with the club.[44]

On 1 October 1977, Pelé closed out his career in an exhibition match between the Cosmos and Santos. Santos arrived in New York after previously defeating the Seattle Sounders in New Jersey, 2–0. The match was played in front of a sold-out crowd at Giants Stadium and was televised in the United States on ABC's Wide World of Sports as well as throughout the world. Pelé's father and wife both attended the match, as well as Muhammad Ali and Bobby Moore.[45]

International career

Pelé's first international match was a 2–1 defeat against Argentina on 7 July 1957 at the Maracanã.[46][47] In that match, he scored his first goal for Brazil aged 16 years and nine months, and he remains the youngest goalscorer for his country.[48][49]

1958 World Cup

Pelé arrived in Sweden sidelined by a knee injury but on his return from the treatment room, his colleagues stood together and insisted upon his selection.[50] His first match was against the USSR in the third match of the first round of the 1958 FIFA World Cup, where he gave the assist to Vavá's second goal.[51] He was the youngest player of that tournament, and at the time the youngest ever to play in the World Cup.[note 2][47] Against France in the semi-final, Brazil was leading 2–1 at halftime, and then Pelé scored a hat-trick, becoming the youngest in World Cup history to do so.[53]

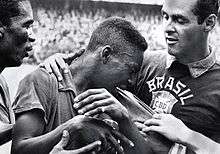

On 29 June 1958, Pelé became the youngest player to play in a World Cup final match at 17 years and 249 days. He scored two goals in that final as Brazil beat Sweden 5–2 in Stockholm, the capital. His first goal where he flicked the ball over a defender before volleying into the corner of the net, was selected as one of the best goals in the history of the World Cup.[54] Following Pelé's second goal, Swedish player Sigvard Parling would later comment; "When Pelé scored the fifth goal in that Final, I have to be honest and say I felt like applauding".[55] When the match ended, Pelé passed out on the field, and was revived by Garrincha.[56] He then recovered, and was compelled by the victory to weep as he was being congratulated by his teammates. He finished the tournament with six goals in four matches played, tied for second place, behind record-breaker Just Fontaine, and was named best young player of the tournament.[57]

It was in the 1958 World Cup that Pelé began wearing a jersey with number 10. The event was the result of disorganization: the leaders of the Brazilian Federation did not send the shirt numbers of players and it was up to FIFA to choose the number 10 shirt to Pelé who was a substitute on the occasion.[58] The press proclaimed Pelé the greatest revelation of the 1958 World Cup, and he was also retroactively given the Silver Ball as the second best player of the tournament, behind Didi.[55]

South American Championship

Pelé also played in the South American Championship. In the 1959 competition he was named best player of the tournament and was top scorer with 8 goals, as Brazil came second despite being unbeaten in the tournament.[55][59] He scored in five of Brazil's six games, including two goals against Chile and a hat-trick against Paraguay.[60]

1962 World Cup

When the 1962 World Cup started, Pelé was the best rated player in the world.[61] In the first match of the 1962 World Cup in Chile, against Mexico, Pelé assisted the first goal and then scored the second one, after a run past four defenders, to go up 2–0.[62] He injured himself in the next game while attempting a long-range shot against Czechoslovakia.[63] This would keep him out of the rest of the tournament, and forced coach Aymoré Moreira to make his only lineup change of the tournament. The substitute was Amarildo, who performed well for the rest of the tournament. However, it was Garrincha who would take the leading role and carry Brazil to their second World Cup title, after beating Czechoslovakia at the final in Santiago.[64]

1966 World Cup

Pelé was the most famous footballer in the world during the 1966 World Cup in England, and Brazil fielded some world champions like Garrincha, Gilmar and Djalma Santos with the addition of other stars like Jairzinho, Tostão and Gérson, leading to high expectations for them.[65] Brazil was eliminated in the first round, playing only three matches.[65] The World Cup was marked, among other things, for brutal fouls on Pelé that left him injured by the Bulgarian and Portuguese defenders.[66]

Pelé scored the first goal from a free kick against Bulgaria, becoming the first player to score in three successive FIFA World Cups, but due to his injury, a result of persistent fouling by the Bulgarians, he missed the second game against Hungary.[65] His coach stated that after the first game he felt "every team will take care of him in the same manner".[66] Brazil lost that game and Pelé, although still recovering, was brought back for the last crucial match against Portugal at Goodison Park in Liverpool by the Brazilian coach Vicente Feola. Feola changed the entire defense, including the goalkeeper, while in midfield he returned to the formation of the first match. During the game, Portugal defender João Morais fouled Pelé, but was not sent off by referee George McCabe; a decision retrospectively viewed as being among the worst refereeing errors in World Cup history.[67] Pelé had to stay on the field limping for the rest of the game, since substitutes were not allowed at that time.[67] After this game he vowed he would never again play in the World Cup, a decision he would later change.[61]

1970 World Cup

Pelé was called to the national team in early 1969, he refused at first, but then accepted and played in six World Cup qualifying matches, scoring six goals.[68] The 1970 World Cup in Mexico was expected to be Pelé's last. Brazil's squad for the tournament featured major changes in relation to the 1966 squad. Players like Garrincha, Nilton Santos, Valdir Pereira, Djalma Santos and Gilmar had already retired. However, Brazil's 1970 World Cup squad, which included players like Pelé, Rivelino, Jairzinho, Gérson, Carlos Alberto Torres, Tostão and Clodoaldo, is often considered to be the greatest football team in history.[69][70]

The front five of Jairzinho, Pelé, Gerson, Tostão and Rivelino together created an attacking momentum, with Pelé having a central role in Brazil's way to the final.[72] All of Brazil's matches in the tournament (except the final) were played in Guadalajara, and in the first match against Czechoslovakia, Pelé gave Brazil a 2–1 lead, by controlling Gerson's long pass with his chest and then scoring. In this match Pelé attempted to lob goalkeeper Ivo Viktor from the half-way line, only narrowly missing the Czechoslovak goal.[73] Brazil went on to win the match, 4–1. In the first half of the match against England, Pelé nearly scored with a header that was saved by the England goalkeeper Gordon Banks.[74] In the second half, he controlled a cross from Tostão before flicking the ball to Jairzinho who scored the only goal.[75]

Against Romania, Pelé scored two goals, with Brazil winning by a final score of 3–2. In the quarterfinals against Peru, Brazil won 4–2, with Pelé assisting Tostão for Brazil's third goal. In their semi-final match, Brazil faced Uruguay for the first time since the 1950 World Cup final round match. Jairzinho put Brazil ahead 2–1, and Pelé assisted Rivelino for the 3–1. During that match, Pelé made one of his most famous plays.[73] Tostão passed the ball for Pelé to collect which Uruguay's goalkeeper Ladislao Mazurkiewicz took notice of and ran off his line to get the ball before Pelé. However, Pelé got there first and fooled Mazurkiewicz with a feint by not touching the ball, causing it to roll to the goalkeepers left, while Pelé went to the goalkeepers right. Pelé ran around the goalkeeper to retrieve the ball and took a shot while turning towards the goal, but he turned in excess as he shot, and the ball drifted just wide of the far post.[76]

Brazil played Italy in the final at the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City.[77] Pelé scored the opening goal with a header after outjumping Italian defender Tarcisio Burgnich. Brazil's 100th World Cup goal, Pelé's leap of joy into the arms of teammate Jairzinho in celebrating the goal is regarded as one of the most iconic moments in World Cup history.[78] He then made assists on Brazil's third goal, scored by Jairzinho, and the fourth finished by Carlos Alberto. The last goal of the game is often considered the greatest team goal of all time because it involved all but two of the team's outfield players. The play culminated after Pelé made a blind pass that went into Carlos Alberto's running trajectory. He came running from behind and struck the ball to score.[79] Brazil won the match 4–1, keeping the Jules Rimet Trophy indefinitely, and Pelé received the Golden Ball as player of the tournament.[55][80] Burgnich, who marked Pelé during the final, was quoted saying "I told myself before the game, he's made of skin and bones just like everyone else – but I was wrong".[81]

Pelé's last international match was on 18 July 1971 against Yugoslavia in Rio de Janeiro. With Pelé on the field, the Brazilian team's record was 67 wins, 14 draws and 11 losses.[68] Brazil never lost a match while fielding both Pelé and Garrincha.[82]

Style of play

Pelé has also been known for connecting the phrase "The Beautiful Game" with football.[83] A prolific goalscorer, he was known for his ability to anticipate opponents in the area and finish off chances with an accurate and powerful shot with either foot.[34][84][85] Pelé was also a hard-working team-player, and a complete forward, with exceptional vision and intelligence, who was recognised for his precise passing, and ability to link-up with teammates and provide them with assists.[86][87][88]

In his early career, he played in a variety of attacking positions. Although he usually operated inside the penalty area as a main striker or centre forward, his wide range of skills also allowed him to play in a more withdrawn role, as an inside forward or second striker, or out wide.[73][86][89] In his later career, he took on more of a deeper playmaking role behind the strikers, often functioning as an attacking midfielder.[90][91] Pelé's unique playing style combined speed, creativity, and technical skill with physical power, stamina, and athleticism. His excellent technique, balance, flair, agility, and dribbling skills enabled him to beat opponents with the ball, and frequently saw him use sudden changes of direction and elaborate feints in order to get past players, such as his trademark move, the drible da vaca.[73][89][92] Another one of his signature moves was the paradinha, or little stop.[note 3][93]

Despite his relatively small stature, 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m),[94] he excelled in the air, due to his heading accuracy, timing, and elevation.[84][87][92][95] Renowned for his bending shots, he was also an accurate free-kick taker, and penalty taker, although he often refrained from taking penalties, stating that he believed it to be a cowardly way to score.[96][97]

Pelé was also known to be a fair and highly influential player, who stood out for his charismatic leadership and sportsmanship on the pitch. His warm embrace of Bobby Moore following the Brazil vs England game at the 1970 World Cup is viewed as the embodiment of sportsmanship, with The New York Times stating the image "captured the respect that two great players had for each other. As they exchanged jerseys, touches and looks, the sportsmanship between them is all in the image. No gloating, no fist-pumping from Pelé. No despair, no defeatism from Bobby Moore."[98] Pelé also earned a reputation for often being a decisive player for his teams, due to his tendency to score crucial goals in important matches.[99][100][101]

Reception and legacy

—US President Ronald Reagan, greeting Pelé at the White House.[21]

Pelé is one of the most lauded players in history and is frequently ranked the best player ever.[102][103][104] Among his contemporaries, Dutch star Johan Cruyff stated; "Pelé was the only footballer who surpassed the boundaries of logic."[21] Brazil's 1970 FIFA World Cup-winning captain Carlos Alberto Torres opined; "His great secret was improvisation. Those things he did were in one moment. He had an extraordinary perception of the game."[21] Tostão, his strike partner at the 1970 World Cup; "Pelé was the greatest – he was simply flawless. And off the pitch he is always smiling and upbeat. You never see him bad-tempered. He loves being Pelé."[21] His Brazilian teammate Clodoaldo commented on the adulation he witnessed; "In some countries they wanted to touch him, in some they wanted to kiss him. In others they even kissed the ground he walked on. I thought it was beautiful, just beautiful."[21]

Pelé is the greatest player of all time. He reigned supreme for 20 years. There's no one to compare with him.

Former Real Madrid and Hungary star Ferenc Puskás stated; "The greatest player in history was Di Stéfano. I refuse to classify Pelé as a player. He was above that."[21] Just Fontaine, French striker and leading scorer at the 1958 World Cup; "When I saw Pelé play, it made me feel I should hang up my boots."[21] England's 1966 FIFA World Cup-winning captain Bobby Moore commented: "Pelé was the most complete player I've ever seen, he had everything. Two good feet. Magic in the air. Quick. Powerful. Could beat people with skill. Could outrun people. Only five feet and eight inches tall, yet he seemed a giant of an athlete on the pitch. Perfect balance and impossible vision. He was the greatest because he could do anything and everything on a football pitch. I remember Saldanha the coach being asked by a Brazilian journalist who was the best goalkeeper in his squad. He said Pelé. The man could play in any position".[84] Former Manchester United striker and member of England's 1966 FIFA World Cup-winning team Sir Bobby Charlton stated; "I sometimes feel as though football was invented for this magical player."[21] During the 1970 World Cup, when Manchester United defender Paddy Crerand (who was part of the ITV panel) was asked; "How do you spell Pelé?", he replied with the response; "Easy: G-O-D."[21]

Accolades

Since retiring, Pelé has continued to be lauded by players, coaches, journalists and others. Brazilian attacking midfielder Zico, who represented Brazil at the 1978, 1982 and 1986 FIFA World Cup, stated; "This debate about the player of the century is absurd. There's only one possible answer: Pelé. He's the greatest player of all time, and by some distance I might add".[55] French three time Ballon d'Or winner Michel Platini said; "There's Pelé the man, and then Pelé the player. And to play like Pelé is to play like God." Joint FIFA Player of the Century, Argentina's 1986 FIFA World Cup-winning captain Diego Maradona stated; "It's too bad we never got along, but he was an awesome player".[55] Prolific Brazilian striker Romário, winner of the 1994 FIFA World Cup and player of the tournament; "It's only inevitable I look up to Pelé. He's like a God to us".[55] Five-time FIFA Ballon d'Or winner Cristiano Ronaldo said: "Pelé is the greatest player in football history, and there will only be one Pelé", while José Mourinho, two-time UEFA Champions League winning manager, commented; "I think he is football. You have the real special one – Mr. Pelé."[105] Real Madrid honorary president and former player, Alfredo Di Stéfano, opined: "The best player ever? Pelé. Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo are both great players with specific qualities, but Pelé was better".[106]

Presenting Pelé the Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award, former South African president Nelson Mandela said; "To watch him play was to watch the delight of a child combined with the extraordinary grace of a man in full."[107] US politician and political scientist Henry Kissinger stated, "Performance at a high level in any sport is to exceed the ordinary human scale. But Pelé's performance transcended that of the ordinary star by as much as the star exceeds ordinary performance."[108] After a reporter asked if his fame compared to that of Jesus, Pelé quipped, "There are parts of the world where Jesus Christ is not so well known."[81]

.jpg)

In 1999, the International Federation of Football History & Statistics (IFFHS) voted Pelé the World Player of the Century. That same year, the International Olympic Committee elected him the Athlete of the Century. According to the IFFHS, Pelé is the most successful league goal-scorer in the world, scoring 1281 goals in 1363 games, which included unofficial friendlies and tour games. In 1999, Time magazine named Pelé one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century. During his playing days, Pelé was for a period the highest-paid athlete in the world.[109] Pelé's "electrifying play and penchant for spectacular goals" made him a star around the world. To take full advantage of his popularity, his teams toured internationally.[34] During his career, he became known as "The Black Pearl" (A Pérola Negra), "The King of Football" (O Rei do Futebol), "The King Pelé" (O Rei Pelé) or simply "The King" (O Rei).[6] In 2014, the city of Santos inaugurated the Pelé museum – Museu Pelé – which displays a 2,400 piece collection of Pelé memorabilia.[110] Approximately $22 million was invested in the construction of the museum, housed in a 19th-century mansion.[111]

Personal life

Relationships and children

- By Anizia Machado

- Sandra (1964–2006)

- By Lenita Kurtz

- Flávia (born 1968)

- By Rosemeri dos Reis Cholbi

- Kelly Cristina (born 1967)

- Edson (born 1970)

- Jennifer (born 1978)

- By Assíria Lemos Seixas

- Joshua (born 1996)

- Celeste (born 1996)

Pelé has married three times, and has had several affairs, producing several children.

On 21 February 1966, Pelé married Rosemeri dos Reis Cholbi.[113] They had two daughters and one son: Kelly Cristina (born 13 January 1967), who married Dr. Arthur DeLuca, Jennifer (b. 1978), and their son Edson ("Edinho", b. 27 August 1970). The couple divorced in 1982.[114] In May 2014, Edinho was jailed for 33 years for laundering money from drug trafficking.[115] On appeal the sentence was reduced to 12 years and 10 months.[116]

From 1981 to 1986, Pelé was romantically linked with TV presenter Xuxa, which was influential in launching her career. She was 17 when they started dating.[117] In April 1994, Pelé married psychologist and gospel singer Assíria Lemos Seixas, who gave birth on 28 September 1996 to twins Joshua and Celeste through fertility treatments. The couple divorced in 2008.[118]

Pelé had at least two more children from former affairs. Sandra Machado, who was born from an affair Pelé had in 1964 with a housemaid, Anizia Machado, fought for years to be acknowledged by Pelé, who refused to submit to DNA tests.[119][120][121] Although she was recognized by courts as his biological daughter based on DNA evidence in 1993, Pelé never acknowledged his eldest daughter even after her death in 2006, nor her two children, Octavio and Gabriel.[120][121] Pelé also had another daughter, Flávia Kurtz, in an extramarital affair in 1968 with journalist Lenita Kurtz. Flávia was recognized by him as his daughter.[119]

At the age of 73, Pelé announced his intention to marry 41-year-old Marcia Aoki, a Japanese-Brazilian importer of medical equipment from Penápolis, São Paulo, whom he had been dating from 2010. They first met in the mid-1980s in New York, before meeting again in 2008.[122] They married in July 2016.[123]

Politics

In 1970, Pelé was investigated by the Brazilian military dictatorship for suspected leftist sympathies. Declassified documents showed Pelé was investigated after being handed a manifesto calling for the release of political prisoners. Pelé himself did not get further involved within political struggles in the country.[124]

In 1976, Pelé was on a Pepsi-sponsored trip in Lagos, Nigeria, when that year's attempted military coup took place. Pelé was trapped in a hotel together with Arthur Ashe and other tennis pros, who were participating in the interrupted 1976 Lagos WCT tournament. Pelé and his crew eventually left the hotel to stay at the residence of Brazil's ambassador as they couldn't leave the country for a couple of days. Later the airport was opened and Pelé left the country disguised as a pilot.[125][126]

In June 2013, he was criticized in public opinion for his conservative views.[127][128] During the 2013 protests in Brazil, Pelé asked for people to "forget the demonstrations" and support the Brazil national team.[129]

Health

In 1977, Brazilian media reported that Pelé had his right kidney removed.[130] In November 2012, Pelé underwent a successful hip operation.[131] In December 2017, Pelé appeared in a wheelchair at the 2018 World Cup draw in Moscow where he was pictured with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Diego Maradona.[132] A month later he collapsed from exhaustion and was taken to hospital.[132] In 2019, after a hospitalisation because of a urinary tract infection, Pelé underwent surgery to remove kidney stones.[133] In February 2020 his son Edinho reported that Pelé was unable to walk independently and reluctant to leave home, ascribing his condition to a lack of rehabilitation following his hip operation.[134]

After football

In 1994, Pelé was appointed a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador.[137] In 1995, Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso appointed Pelé to the position of Extraordinary Minister for Sport. During this time he proposed legislation to reduce corruption in Brazilian football, which became known as the "Pelé law."[138] Pelé left his position in 2001 after he was accused of involvement in a corruption scandal that stole $700,000 from UNICEF. It was claimed that money given to Pelé's company for a benefit match was not returned after it was cancelled, although nothing was proven, and it was denied by UNICEF.[139][140] In 1997, he received an honorary knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II at a ceremony in Buckingham Palace.[141] Pelé also helped inaugurate the 2006 FIFA World Cup finals, alongside supermodel Claudia Schiffer.[70]

In 1993, Pelé publicly accused the Brazilian football administrator Ricardo Teixeira of corruption after Pelé's television company was rejected in a contest for the Brazilian domestic rights to the 1994 World Cup.[142] Pelé accusations led to an eight-year feud between the pair.[143] As a consequence of the affair, the President of FIFA, João Havelange banned Pelé from the draw for the 1994 FIFA World Cup in Las Vegas. Criticisms over the ban were perceived to have negatively affected Havelange's chances of re-election as FIFA's president in 1994.[142]

Pelé has published several autobiographies, starred in documentary films, and composed musical pieces, including the soundtrack for the film Pelé in 1977.[144] He appeared in the 1981 film Escape to Victory, about a World War II-era football match between Allied prisoners of war and a German team. Pelé starred alongside other footballers of the 1960s and 1970s, with actors Michael Caine, and Sylvester Stallone.[145] in 1969, Pelé starred in a telenovela called Os Estranhos, about first contact with aliens. It was created to drum up interest in the Apollo missions.[146] In 2001, had a cameo role in the satire film, Mike Bassett: England Manager.[147]

In November 2007, Pelé was in Sheffield, England to mark the 150th anniversary of the world's oldest football club, Sheffield F.C.[148] Pelé was the guest of honour at Sheffield's anniversary match against Inter Milan at Bramall Lane.[148] As part of his visit, Pelé opened an exhibition which included the first public showing in 40 years of the original hand-written rules of football.[148] Pelé scouted for Premier League club Fulham in 2002.[149] He made the draw for the qualification groups for the 2006 FIFA World Cup finals.[150] On 1 August 2010, Pelé was introduced as the Honorary President of a revived New York Cosmos, aiming to field a team in Major League Soccer.[151] In August 2011, ESPN reported that Santos were considering bringing him out of retirement for a cameo role in the 2011 FIFA Club World Cup, although this turned out to be false.[152]

The most notable area of Pelé's life since football is his ambassadorial work. In 1992, he was appointed a UN ambassador for ecology and the environment.[153] He was also awarded Brazil's Gold Medal for outstanding services to the sport in 1995. In 2012, Pelé was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh for "significant contribution to humanitarian and environmental causes, as well as his sporting achievements".[154]

In 2009, Pelé assisted the Rio de Janeiro bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics. In July 2009 he spearheaded the Rio 2016 presentation to the Association of National Olympic Committees of Africa General Assembly in Abuja, Nigeria.[155]

On 12 August 2012, Pelé was an attendee at the 2012 Olympic hunger summit hosted by UK Prime Minister David Cameron at 10 Downing Street, London, part of a series of international efforts which have sought to respond to the return of hunger as a high-profile global issue.[156][157] Later on the same day, Pelé appeared at the closing ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, following the handover section to the next host city for the 2016 Summer Olympics, Rio de Janeiro.[158]

In March 2016, Pelé filed a lawsuit against Samsung Electronics in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois seeking US$30 million in damages claiming violations under the Lanham Act for false endorsement and a state law claim for violation of his right of publicity.[159] The suit alleged, that at one point Samsung and Pelé came close to entering into a licensing agreement for Pelé to appear in a Samsung advertising campaign. Samsung abruptly pulled out of the negotiations. The October 2015 Samsung ad in question, included a partial face shot of a man who allegedly "very closely resembles" Pelé and also a superimposed high-definition television screen next to the image of the man featuring a "modified bicycle or scissors-kick", often used by Pelé.[159]

Honours

Santos

- Campeonato Brasileiro Série A (6): 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1968[160]

- Copa Libertadores (2): 1962, 1963[23][161]

- Intercontinental Cup (2): 1962, 1963[162]

- Intercontinental Supercup: 1968[162]

- Campeonato Paulista (10): 1958, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1964, 1965, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1973[note 4][164]

- Torneio Rio-São Paulo (4): 1959, 1963, 1964, 1966[note 5][150]

New York Cosmos

- North American Soccer League, Soccer Bowl: 1977[166]

- North American Soccer League, Atlantic Conference Championship: 1977[166]

Brazil

- FIFA World Cup (3): 1958, 1962, 1970[167]

Individual

In December 2000, Pelé and Maradona shared the prize of FIFA Player of the Century by FIFA.[168] The award was originally intended to be based upon votes in a web poll, but after it became apparent that it favoured Diego Maradona, many observers complained that the Internet nature of the poll would have meant a skewed demographic of younger fans who would have seen Maradona play, but not Pelé. FIFA then appointed a "Family of Football" committee of FIFA members to decide the winner of the award together with the votes of the readers of the FIFA magazine. The committee chose Pelé. Since Maradona was winning the Internet poll, however, it was decided he and Pelé should share the award.[169]

- Copa Libertadores Top Scorer: 1965[170]

- Intercontinental Cup Top Scorer (2): 1962, 1963[171][172][173]

- Campeonato Brasileiro Série A Top Scorer (3): 1961, 1963, 1964[174]

- Campeonato Paulista Top Scorer (11): 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1969, 1973[150]

- Torneio Rio-São Paulo Top Scorer: 1963[175]

- Bola de Prata: 1970[176]

- FIFA World Cup Best Young Player: 1958[57]

- FIFA World Cup Silver Ball: 1958

- FIFA World Cup Golden Ball (Best Player): 1970[55]

- South American Championship Best Player: 1959[59]

- South American Championship Top Scorer: 1959[60]

- FIFA Ballon d'Or Prix d'Honneur: 2013[177]

- World Player of the Century, by the IFFHS: 1999[178][179]

- South American player of the century, by the IFFHS: 1999[178][179]

- Elected best Brazilian player of the century, by the IFFHS: 2006[180]

- France Football's Ballon d'Or (7): 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1964, 1970 – Le nouveau palmarès (the new winners)[181][182]

- FIFA Player of the Century: 2000[55]

- FIFA Order of Merit: 1984[183]

- FIFA Centennial Award: 2004[184]

- FIFA 100 Greatest Living Footballers: 2004[185]

- Winner of France Football's World Cup Top-100 1930–1990[186]

- BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year: 1970[187]

- BBC Sports Personality of the Year Lifetime Achievement Award: 2005[188]

- Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award: 2000[189]

- Greatest football player to have ever played the game, by Golden Foot: 2012[190]

- Athlete of the Century, by Reuters News Agency: 1999[191]

- Athlete of the Century, elected by International Olympic Committee: 1999[192]

- South American Footballer of the Year: 1973[193]

- Football Player of the Century, elected by France Football's Ballon d'Or Winners: 1999[194]

- Inducted into the American National Soccer Hall of Fame: 1992[184]

- World Team of the 20th Century: 1998[195]

- TIME: One of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th century: 1999[196]

- World Soccer Greatest XI of All Time: 2013[197]

- FWA Tribute Award: 2018[198]

- Included in the North American Soccer League (NASL) All-Star team (3): 1975, 1976, 1977[199]

- Number 10 retired by the New York Cosmos as a recognition to his contribution to the club: 1977[200][201]

- Elected Citizen of the World, by the United Nations: 1977[202]

- Elected Goodwill Ambassador, by UNESCO: 1993[202]

Orders

- Knight of the Order of Rio Branco: 1967[203]

- Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (honorary knighthood): 1997[204]

- Elected Commander of the Order of Rio Branco after scoring the thousandth goal: 1969[202]

- Awarded with the Cross of the Order of the Republic of Hungary: 1994[202]

- Awarded the FIFA Order as a tribute to his 80 years as a sports institution: 1984[202]

- Awarded with the Order of Merit of South America, by CONMEBOL: 1984[202]

- Awarded with the Order of Champions, by the Organization of Catholic Youth in the USA: 1978[202]

- He was awarded the National Order of Merit, by the government of Brazil: 1991[202]

- Olympic Order, by the International Olympic Committee: 2016[205]

Personal records

- Brazil national football team: All-time leading goalscorer: 77 goals (95 goals including unofficial friendlies)[206]

- All-time South American leading international goalscorer: 77 goals[207]

- Santos: All-time leading goalscorer: 643 goals in 656 competitive games[208]

- Intercontinental Cup: All-time leading goalscorer: 7 goals[209]

- World record number of hat-tricks: 92[210]

- Guinness World Records: Most career goals (football): 1283 goals in 1363 games[211]

- Guinness World Records: Most FIFA World Cup winners' medals: three[211][212]

- Guinness World Records: Youngest winner of a FIFA World Cup: 17 years and 249 days in 1958 FIFA World Cup[213]

- Youngest goalscorer in a FIFA World Cup: 17 years and 239 days (Brazil v Wales 1958)[55][214]

- Youngest player to score a hat-trick in a FIFA World Cup: 17 years and 244 days (Brazil v France 1958)[214]

- Youngest player to play in a FIFA World Cup Final: 17 years and 249 days (Brazil v Sweden 1958)[215]

- Youngest goalscorer in a FIFA World Cup Final: 17 years and 249 days (Brazil v Sweden 1958)[215]

- Most assists provided in FIFA World Cup history: 10, (1958–1970)[216]

- Most assists provided in a single FIFA World Cup tournament: 7, (1970)[216]

- Most assists provided in a FIFA World Cup Final: 3, (1958 and 1970)[217]

- Top scorer in a FIFA World Cup Final (joint with Vavá, Geoff Hurst and Zinedine Zidane): 3 goals[218]

- Youngest goalscorer of the Paulista Championship: 1957 – Santos (he was 17 years old during the competition)

- Youngest FIFA World Cup winner: in 1958 – Brazil (17 years)

- Youngest two-time FIFA World Cup winner: in 1962 – Brazil (21 years)

- Record Top scorer in a calendar year: in 1959 – 127 goals[219][220]

Career statistics

Club

Pelé's goalscoring record is often reported by FIFA as being 1281 goals in 1363 games.[55] This figure includes goals scored by Pelé in friendly club matches, like international tours Pelé completed with Santos and the New York Cosmos, and a few games Pelé played in for the Brazilian armed forces teams during his national service in Brazil.[221] He was listed in the Guinness World Records for most career goals scored in football.[222]

The tables below record every goal Pelé scored in major club competitions for Santos and the New York Cosmos.

| Club | Season | Campeonato Paulista | Rio-São Paulo[note 6] | Campeonato Brasileiro Série A[note 7] | Domestic competitions Sub-total |

International Competitions | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copa Libertadores | Intercontinental Cup | |||||||||||||||

| Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | |||

| Santos | 1956 | 0* | 0* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 1957 | 14+15* | 19+17*[note 8][note 9] | 9 | 5 | 38* | 41* | 38* | 41* | ||||||||

| 1958 | 38 | 58 | 8 | 8 | 46 | 66 | 46* | 66* | ||||||||

| 1959[226] | 32 | 45 | 7 | 6 | 4* | 2* | 39 | 51 | 43* | 53* | ||||||

| 1960[227] | 30 | 33 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33* | 33* | ||

| 1961 | 26 | 47 | 7 | 8 | 5* | 7 | 33 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38* | 62* | ||

| 1962 | 26 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 5* | 2* | 26 | 37 | 4* | 4* | 2 | 5 | 37* | 48* | ||

| 1963[228] | 19 | 22 | 8 | 14 | 4* | 8 | 27 | 36 | 4* | 5* | 1 | 2 | 36 | 51* | ||

| 1964 | 21 | 34 | 4 | 3 | 6* | 7 | 25 | 37 | 0* | 0* | 0 | 0 | 31* | 44* | ||

| 1965 | 30 | 49 | 7 | 5 | 4* | 2* | 37 | 54 | 7* | 8 | 0 | 0 | 48* | 64* | ||

| 1966 | 14 | 13 | 0* | 0* | 5* | 2* | 14* | 13* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19* | 15* | ||

| 1967 | 18 | 17 | 14* | 9* | 32* | 26* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32* | 26* | ||||

| 1968 | 21 | 17 | 17* | 11* | 38* | 28* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38* | 28* | ||||

| 1969 | 25 | 26 | 12* | 12* | 37* | 38* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37* | 38* | ||||

| 1970 | 15 | 7 | 13* | 4* | 28* | 11* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28* | 11* | ||||

| 1971 | 19 | 8 | 21 | 1 | 40 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 9 | ||||

| 1972 | 20 | 9 | 16 | 5 | 36 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 14 | ||||

| 1973 | 19 | 11 | 30 | 19 | 49 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 30 | ||||

| 1974 | 10 | 1 | 17 | 9 | 27 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 10 | ||||

| Total | 412 | 470 | 53 | 49 | 173* | 100* | 638* | 619* | 15 | 17[note 10] | 3 | 7 | 656 | 643 | ||

- * Indicates that the number was deduced from the list of rsssf.com and this list of Pelé games.

| Club | Season | League | Post season | Other | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| NY Cosmos | 1975 | 9 | 5 | – | – | 14 | 10 | 23 | 15 |

| 1976 | 22 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 11 | 42 | 26 | |

| 1977 | 25 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 42 | 23 | |

| Total | 56 | 31 | 8 | 6 | 43 | 27 | 107 | 64 | |

International

Pelé is the top scorer of the Brazil national football team with 77 goals in 92 official appearances.[55] In addition, he scored 18 times in 22 unofficial games. This makes an unofficial total of 114 games and 95 goals. He also scored 12 goals and is credited with 10 assists in 14 World Cup appearances, including 4 goals and 7 assists in 1970.[12] Pelé shares with Uwe Seeler, Miroslav Klose and Cristiano Ronaldo the achievement of being the only players to have scored in four separate World Cup tournaments.[229][230]

Source:[68]

| Team | Year | Tournament | Friendly | Total | Goal average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | |||

| Brazil | 1957 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| 1958 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 1.13 | |

| 1959 | 8 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 1.22 | |

| 1960 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 0.89 | |

| 1961 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | |

| 1962 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 1.00 | |

| 1963 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 0.88 | |

| 1964 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0.67 | |

| 1965 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 1.13 | |

| 1966 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 0.85 | |

| 1967 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | |

| 1968 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 0.63 | |

| 1969 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 0.71 | |

| 1970 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 15 | 8 | 0.57 | |

| 1971 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | |

| Total | 41 | 43 | 51 | 34 | 92 | 77 | 0.84 | |

| Career total (incl. unofficial matches)[231] | 41 | 43 | 69 | 56 | 114 | 95 | 0.83 | |

Summary

Pelé numbers differ between sources mostly due to friendly games. The RSSSF states that Pelé scored 767 goals in 831 official games, 1281 goals in 1365 overall while he was active, and 1284 in 1375 taking into account benefit games after retirement.[209] The following table is a compendium of sources that include data from Santos and FIFA official websites among others.[232]

| Matches | Goals | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Tournaments | 702 | 656 | 0.94 |

| International Tournaments | 18 | 24 | 1.33 |

| Brazil national football team | 92 | 77 | 0.84 |

| Official | 812 | 757 | 0.93 |

| Friendly matches and defunct Tournaments | 554 | 526 | 0.95 |

| Total | 1366 | 1283 | 0.94 |

| Matches | Goals | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| International matches (Official and Friendlies) | 503 | 479 | 0.95 |

| Domestic matches (Official and Friendlies) | 863 | 804 | 0.93 |

| Total | 1366 | 1283 | 0.94 |

| Matches | Goals | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Santos FC[233] | 1116 | 1091 | 0.98 |

| New York Cosmos[233] | 111 | 65 | 0.59 |

| Brazil | 114 | 95 | 0.83 |

| Other | 25 | 32 | 1.28 |

| Total | 1366 | 1283 | 0.94 |

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Os Estranhos | Plínio Pompeu | TV Series |

| 1971 | O Barão Otelo no Barato dos Bilhões | Dr. Arantes / Himself | |

| 1972 | A Marcha | Chico Bondade | |

| 1981 | Escape to Victory | Corporal Luis Fernandez | |

| 1983 | A Minor Miracle | Himself | |

| 1985 | Pedro Mico | ||

| 1986 | Hotshot | Santos | |

| 1986 | Os Trapalhões e o Rei do Futebol | Nascimento | |

| 1989 | Solidão, Uma Linda História de Amor | ||

| 2016 | Pelé: Birth of a Legend | Man sitting in hotel lobby | Cameo appearance |

See also

- Pelé runaround move

- List of men's footballers with 50 or more international goals

- List of men's footballers with 500 or more goals

Notes

- Pelé presumed that it was an insult since the word had no meaning in Portuguese. He discovered in the 2000s that the word meant "miracle" in Hebrew.[5]

- The mark was surpassed by Northern Ireland's Norman Whiteside in the 1982 FIFA World Cup. He scored his first World Cup goal against Wales in quarter-finals, the only goal of the match, to help Brazil advance to semi-finals, while becoming the youngest ever World Cup goalscorer at 17 years and 239 days.[52]

- Pelé would stop in the middle of a run-up to a penalty kick before shooting the ball; goalkeepers complained that this gave strikers an unfair advantage, however, and in the 1970s, FIFA banned this move from competitions.[93]

- The 1973 Paulista was held jointly with Portuguesa.[163][150]

- The 1964 Torneio Rio-São Paulo was held jointly with Botafogo.[165]

- Soccer Europe compiled this list from The Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.[223]

- Statistics from 1957 to 1974 for the Taça de Prata, Taça Brasil and Copa Libertadores were taken from Soccer Europe website. Soccer Europe lists The Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation, but do not give a season-by-season breakdown.[224]

- In 1957, the Paulista Championship was divided in two phases: Blue Series and White Series. In the first, Pelé scored 19 goals in 14 games, and in the Blue Series, scored 17 goals in 15 games. See [225]

- This number was inferred from a Santos fixture list from rsssf.com and this list of games Pelé played.

- Statistics from 1957 to 1974 for the Taça de Prata, Taça Brasil and Copa Libertadores were taken from Soccer Europe website. Soccer Europe lists The Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation, but do not give a season-by-season breakdown.[224]

References

- Pelé & Fish 1977, p. 18–19.

- Pelé 2008, p. 14.

- Narcía, Eva. "Un siglo, diez historias" (in Spanish). BBC World Service. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- "From Edson to Pelé: my changing identity". The Guardian. London. 12 May 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- Winterman, Denise (4 January 2006). "Taking the Pelé". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Pelé". Biography.com, via A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Heizer 1997, p. 173.

- Magill 1999, p. 2950.

- "Pele Speaks of Benefits of Futebol de Salão". International Confederation of Futebol de Salão. 24 May 2006. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016.

- Massarela, Louis (7 September 2016). "Exclusive interview: Pele on his Santos years". FourFourTwo. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Marcus 1976, p. 20.

- "Pele helps Brazil to World Cup title". History. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Da Mata, Alessandro (26 October 2007). "Mesário da estréia de Pelé lembra atrapalhada" (in Portuguese). Sâo Paulo: LANCE!. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008.

- "Pelé, auguri a Ronaldo. E rivela: "Sono stato vicino alla Juve"". La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). 18 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Cecere, Nicola (26 May 2016). "Moratti: "Pelé era dell'Inter, ma il presidente del Santos cambiò idea..."" [Moratti: "Pelé was Inter's, but the president of Santos changed his mind ..."]. La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Chelala, Cesar (2014). "Pele, Maradona and Messi: soccer's holy trinity". Japan Times.

- "Campeonato Paulista: Artilheiros da história – 2". Brasil em Folhas (in Portuguese). 17 January 2008.

- Unzelte, Celso; Varanda, Pedro; Cammarota, Giuseppe; Barreto Berwanger, Alexandre Magno (2011). "Fichas Técnicas De Jogos Que Decidiram O Torneio Rio-Sâo Paulo" (in Portuguese). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- Matta, Fernando; Varanda, Pedro; Barreto Berwanger, Alexandre Magno; Unzelte, Celso; Leme de Arruda, Marcelo (2009). "Torneio Rio-São Paulo 1960" (in Portuguese). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 December 2009.

- "Santos revive spirit of Pele". BBC Sport. 16 February 2003. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "What they said about Pele". FIFA. 16 Jul 2019.

- Dunmore 2015, p. 290.

- Pierrend, José Luis; Beuker, John; Ciullini, Pablo; Gorgazzi, Osvaldo. "Copa Libertadores de América 1962". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- "Intercontinental Cups 1962 and 1963". FIFA. 15 January 2015

- "Extraordinary Pele crowns Santos in Lisbon". FIFA. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Vickery, Tim (23 December 2009). "Will South Africa 2010 produce a new Pele?". BBC Sport. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "1963: With an amazing Pele, Brazil's Santos wins their second Copa Libertadores Tournament". CONMEBOL. 12 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Bassorelli, Gerardo. "En los años sesenta, Peñarol y Santos protagonizaron inolvidables batallas por la Libertadores, generando una rivalidad que transformó a este duelo en el primer clásico que tuvo la Copa". LaRed21. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- Andrés, Juan Pablo; Ballesteros, Frank; Di Maggio, Robert. "Copa Libertadores – Topscorers". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015.

- "Pele scores 1,000th goal". History.com. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Pele receives tribute for 1959 goal". The Times. Malta. 31 August 2006. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Remembering Pele's gol de placa". FIFA. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Bellos 2003, p. 244.

- "Pelé (Brazilian Athlete)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Santos – Pelé edges Eusebio as Santos defend title FIFA. 23 April 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2011

- Apple Jr., R. W. (4 July 1975). "Pele to Play Soccer Here for $7‐Million". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Lewis, Michael (30 September 2017). "How Pelé lit up soccer in America and left a legacy fit for a king". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Yaisinis, Alex (21 June 1975). "Swarming Fans Injure Pele". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Lewis, Michael (2 June 2015). "40 years on: how New York Cosmos lured Pelé to a football wasteland". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- "Football and Politics in the Shadow of the Cedars, 2000–2015 | Middle East Policy Council". mepc.org. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Brazilian Football Legend Pelé played for Lebanese Nejmeh SC in 1975". Blog Baladi. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Lebanon's national teams fly above entrenched sectarianism among supporters". The National. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Pelé's Hail Mary in Santo Domingo". Life. 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- Dunmore 2011, p. 198.

- Freedman 2014, p. 165.

- "Seven the number for Pele". FIFA. 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Williams, Bob (28 October 2008). "Top 10: Young sporting champions". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Lang, Jack (7 July 2017). "60 years ago today, Pele scored his first Brazil goal and began a career that would change football". The Independent. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Morrison, Neil; Gandini, Luca; Villante, Eric. "Oldest and Youngest Players and Goal-scorers in International Football". Rec. Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- "Simply the best ever". ABC News. 25 April 2002. Archived from the original on 2 January 2003.

- "Copa 1958". Terra Networks (in Portuguese). 2006.

- Gault, Matt (9 July 2015). "Norman Whiteside: world beater at 17, retired by 26". These Football Times. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Hawkes, Will (26 May 2010). "Flashback No 6. Sweden 1958: Pele's genius propels Brazil to first title". The Independent.

- FIFA World Cup Goal of the Century FIFA. 30 May 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2011

- "The King of football". FIFA. 2015. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Pelé (13 May 2006). "How a teenager took the world by wizardry". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- 1958 FIFA World Cup Sweden – Awards FIFA. Retrieved 6 May 2011

- Spencer, Jamie (7 September 2015). "The Fascinating Stories Behind 13 Famous Shirt Numbers". 90 Min. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- Tabeira, Martín (19 July 2007). "The Copa América Archive – Trivia". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Tabeira, Martín (2009). "Southamerican Championship 1959 (1st Tournament)". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- "PELE – International Football Hall of Fame". ifhof.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- Kunti, Samindra (23 October 2015). "A Look Back at Pelé's Legendary Takedown of Mexico's Defense at the 1962 World Cup". Remezcla.

- Downie, Andrew (6 July 2014). "Brazilians look to Pele and 1962 for Cup-winning omen". Reuters. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- Moore, Glenn (3 June 2006). "Pele: The Greatest". The Independent. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "1966 FIFA World Cup England: Group 3". FIFA. Retrieved 16 January 2015

- Burnton, Simon. "Why not everyone remembers the 1966 World Cup as fondly as England". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Collins, Nick (9 July 2010). "World Cup final: 10 top World Cup refereeing errors". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- Mamrud, Roberto. "Edson Arantes do Nascimento "Pelé" – Goals in International matches". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Bell, Jack (11 July 2007). "1970 Brazilian Soccer Team Voted Best Ever". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Joseph, Paul (9 April 2008). "The boys from Brazil: On the trail of football's dream team". The Independent. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- Vickery, Tim (4 April 2017). "Zagallo and Tostao". The Blizzard. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017.

- "Mexico in thrall to Brazilians' beautiful game". FIFA. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Hughes, Rob (29 December 1999). "The Greatest? For Century, Pele Eclipses Muhammad Ali". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Hattenstone, Simon (30 June 2003). "And God created Pelé". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "Jairzinho and Banks reunited". BBC. 2 August 2002. Retrieved 28 July 2003.

- Joyce, Stephen (12 January 2010). "Mexico 1970: Brazilians show all how beautiful game should be played". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010.

- "World Championship – Jules Rimet Cup 1970 Final". FIFA. Retrieved 17 December 2014

- "Coca-Cola Memorable Celebrations 1: Pele's Iconic Leap of Joy After Scoring Brazil's Century Goal". Goal. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Benson, Andrew (2 June 2006) "The perfect goal". BBC Sport. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- "Brazil's heroes of 1970 relive their days of glory". FIFA. 10 June 2000. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Kirby, Gentry (2003). "Pele, King of Futbol". ESPN. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Stevenson, Jonathan (20 January 2008). "Remembering the genius of Garrincha". BBC. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "The World Cup will show why football is still a beautiful game". The Telegraph (12 June 2014).

- Malley, Frank (23 December 1999). "Pele, the perfect player". The Independent. London.

- Bate, Adam (19 March 2015). "Messi? Ronaldo? Pele? Maradona? Who is the greatest of all-time?". Sky Sports. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Massarella, Louis (5 November 2015). "Pele or Puskas? Maradona or Messi? Just who is the best No.10 of all-time?". FourFourTwo. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- Miller, David (12 December 2000). "Maradona's genius cannot eclipse Brazilian master". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Adams, Tom (9 November 2015). "Mesut Ozil's assists at Arsenal make a compelling case for player of the year". ESPN FC. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Pelé and Maradona – two very different number tens". FIFA. 25 January 2001. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- Pelé 2008, p. 41.

- Pastorin, Darwin. "PELE (Edson Arantes do Nascimento)" (in Italian). Treccani: Enciclopedia dello Sport (2002). Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Marino, Giovanni (21 April 2010). "La vita mancina di Mario Corso "Io, tra Herrera, Pelè e Berselli"". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Pelé 2008, p. 112.

- "Pele Player Profile". ESPN FC. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- Radogna, Fiorenzo (1 October 2017). "40 anni fa l'addio al calcio di Pelé: la storia di O Rei, tre volte campione del mondo". Il Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- Miller, Nick (15 June 2015). "Pele Top 10: World Cup glory, with Bobby Moore and goals, goals goals". ESPN FC. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Crosetti, Maurizio (26 May 2014). "Palleggio volante ed esterno destro il mondo conobbe il bambino Pelé". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "A Shot That Captured the Bigger Meaning in Sports". The New York Times. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- Longhi, Lorenzo (18 October 2010). "Il mastino Burgnich: "Il mio Pelé, il migliore di tutti"" (in Italian). sport.sky.it. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Fiori, Stefano (27 June 2018). "Mondiali, la maledizione dei campioni in carica continua" (in Italian). foxsports.it. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Motisi, Domenico (5 October 2017). "Da Pelé a Grosso, i 20 calciatori più determinanti e decisivi ai Mondiali" (in Italian). sport.sky.it. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- "Pele: The greatest of them all". FIFA. 28 June 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Pele tops World Cup legends poll". BBC News. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "The Best of the Best". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010.

- "Pele and Mourinho win BBC awards". BBC. 11 December 2005. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- "Alfredo Di Stefano: Pele is better than Messi and Ronaldo". ESPN. 10 September 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- "Speech by Nelson Mandela at the Inaugural Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award, Monaco 2000". nelsonmandela.org. 25 May 2000. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- Kissinger, Henry (14 June 1999). "PELE: The Phenomenon". Time. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Michelle Roehm McCann (2012). "Boys Who Rocked the World: Heroes from King Tut to Bruce Lee". p. 140. Simon and Schuster

- "Pelé Museum is opened with a 2,400-piece collection and a hologram of the King of Football". Copa 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Brazil inaugurates Pele Museum". ESPN. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Morrissey, Paul (27 April 2013). "Romario trolls Pele on Twitter, says he's a phony Catholic and talks nothing but shit". 101greatgoals.com. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- "Brazil's greatest Pele turns 75". Daily Express. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "Pelé Scores A Marriage Hat Trick". Latin Times. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- "Pele's son Edinho jailed for 33 years for Drug Trafficking". biharprabha.com. Indo-Asian News Service. 1 June 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- "Brazil: Footballer Pele's son Edinho in jail over drug trafficking charges". BBC. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Simón, Yara (28 August 2015). "A Look Back at Xuxa and Pelé's Controversial Relationship". Remezcla. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Brazilian Soccer Legend Pelé Scores A Marriage Hat Trick [VIDEO]". Latin Times. 9 March 2018.

- "Pele's daughter dies of cancer at 42". ESPN. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Pele misses funeral of "daughter he never wanted". People. 18 October 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2014

- "Daughter who sued Pele dies of cancer at 42". ESPN. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "'Minha primeira paixão foi uma japonesa e a última também vai ser', afirma Pelé" ['My first love was a Japanese and will also be the last,' says Pele] (in Portuguese). Brasil Online. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- "Football legend Pele marries 'definitive love'". The Belfast Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "Pelé foi investigado pela ditadura na década de 1970". Brasil em Folhas (in Portuguese). 1 January 1970. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- "How football legend, Arthur Ashe were trapped in Lagos during 1976 coup". Pulse. Retrieved 26 July 2018

- "The story of Lagos’ ill-fated 1976 Professional Tennis Tournament". Africa's Country. Retrieved 26 July 2018

- "Estranho, conservador, desastroso e 'de outro planeta'; comentaristas analisam declarações de Pelé" (in Portuguese). ESPN UOL. 19 June 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Romero, Simon; Neuman, William (21 June 2013). "How Angry Is Brazil? Pelé Now Has Feet of Clay". The New York Times.

- "Estátua de Pelé é "amordaçada" na cidade natal do jogador" (in Portuguese). Terra Networks. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Guilherme Seto, Rafael Reis (28 November 2014). "Pelé tem apenas um rim desde que era jogador de futebol". Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Pele in hospital, hip operation a success, report says". ESPN. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- "Pele recovering in hospital after collapsing with exhaustion". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- Gray, Melissa. "Pele recovering after kidney stone procedure in Brazil". CNN. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Pele: Brazil legend reluctant to leave his home, says son Edinho". Sky Sports. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Hattenstone, Simon (30 June 2003). "And God created Pele". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- Fink, Jesse (13 November 2011). "Pelé's mouth should get a straight red". The Sunday Guardian. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- "World Sport Humanitarian Hall of Fame Inductees – Pelé". Sports Humanitarian. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "Pele Law on sports introduced in Brazil". BBC News. 25 March 1998. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "UNICEF denies Pele corruption reports". SportBusiness.com. Reuters. 23 November 2001. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Pelé slips from Brazil pedestal, The Observer, 25 November 2001.

- "Education: Sir Pele lends his support". The Independent. 3 December 1997. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Darby 2002, p. 110.

- Bellos 2003, p. 114.

- Pelé at AllMusic

- "Escape to Victory remake: who should follow in Pelé's footsteps?". The Guardian. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- "Estranhos extraterrestres chegavam na tela da Excelsior para fazer contato com Pelé" (in Portuguese). Cartâo de Visita. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- "Mike Bassett: England Manager (2001)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Rawcliffe, Jonathan (9 November 2007). "Pelé joins Sheffield celebrations". BBC Sport. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- "Pele scouts for Fulham". BBC Sport. 9 October 2002. Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- Blevins 2011, p. 756.

- Bell, Jack (1 August 2010). "Cosmos Begin Anew, With Eye Toward M.L.S." The New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "Santos hope for Pele comeback". ESPN. 4 August 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- Russell, Scott (1 October 2009). "Reasons why Rio is the right Olympic choice". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Pelé to receive honorary degree". University of Edinburgh. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "World Cup king Pele scores for Rio 2016 at ANOCA assembly". Sports Features.com. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Forsyth, Justin (12 August 2012). "The 2012 hunger summit could be the reallegacy of the Games". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- "Sport stars get behind Olympic hunger summit". 10 Downing Street. 12 August 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Coughlan, Maggie; Perry, Simon (12 August 2012). "Spice Girls, One Direction Bring Olympics to a Dazzling End". People. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- Batterman, L. Robert (23 June 2016). "Soccer Legend Pelé Calls for a Yellow Card against Samsung". The National Law Review. Proskauer Rose LLP. ISSN 2161-3362. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "Pelé o atleta do século". globo.com. 3 January 2016. Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- Pierrend, José Luis; Beuker, John; Ciullini, Pablo; Gorgazzi, Osvaldo. "Copa Libertadores de América 1963". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Recopa Intercontinental 1968/69". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 1 June 2018

- Marcos, Antonio (26 August 2013). "Um campeonato, dois campeões: Conheça a história do Paulista de 73". globo.com.

- "FIFA 18 World Cup Icons player ratings revealed: Pele, Gary Lineker and the 17 classic players". Bristol Post. 27 June 2018.

- Pontes, Ricardo (18 January 2002). "Torneio Rio-São Paulo – List of Champions". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Litterer, David A. (14 May 2010). "North American Soccer League". Rec. Sport. Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "Pelé: Most wins of the FIFA World Cup by a player". Guinness World Records. 14 December 2017.

- "The 20th Century Boys". BBC Sport. 10 December 2000. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- "Split decision-Pele, Maradona each win FIFA century awards after feud". 11 December 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Andres, Juan Pablo; Ballesteros, Frank; Di Maggio, Roberto. "Copa Libertadores – Topscorers". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Intercontinental Club Cup 1963". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- "Intercontinental Cup 1962 – Top Scorer". worldfootball.net.

- "Intercontinental Cup 1963 – Top Scorer". worldfootball.net.

- Carlos, Antonio; Said, On 6 June 2011 at 18:50 (19 March 2010). "Taça Brasil".

- "Todos os Artilheiros do Torneio Rio-São Paulo" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- Casari, Yuri (27 July 2015). "Bola de Prata Placar 1970" (in Portuguese). Escrevendo Futebol. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- "Pele receives FIFA Ballon d'Or Prix d'Honneur". FIFA. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014

- "IFFHS' Century Elections". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- "IFFHS (International Federation of Football History & Statistics)". IFFHS.

- "IFFHS' Players and Keepers of the Century for many countries". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- Crépin, Timothé (2 December 2015). "Pelé devait être le recordman" (in French). France Football.

- Janeiro, Por SporTV comRio de. "Revista faz revisão na Bola de Ouro, e Pelé desbanca Messi nas regras atuais". sportv.com.

- "FIFA Order of Merit" (PDF). FIFA. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Player Bios". U.S. Soccer. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Pele's list of the greatest". BBC. 4 March 2004. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "France Football's World Cup Top-100 1930–1990". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- "Overseas Personality of the Year – previous winners". BBC. 11 November 2003. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- "Sports Personality of the Year celebrates 60th show". BBC. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Lovina Chidi, Sylvia (13 June 2014). The Greatest Black Achievers in History. Lulu. p. 680. ISBN 978-1-291-90933-3.

- "Golden Foot Awards 2012 – Ibrahimovic, Pele, And Cantona". Amfm magazine. Retrieved 8 January 2013

- Bar-On 2014, p. 192.

- "Pelé Fast Facts". CNN. 1 June 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015

- Pierrend, José Luis (22 December 2000). "South American Player of the Year 1973". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- Stokkermans, Karel (23 December 2015). "France Football's Football Player of the Century". Rec.Sport. Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- World All-Time Teams. Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 26 November 2014

- Kissinger, Henry (14 June 1999) Time 100 – PELE: The Phenomenon Time. Retrieved 22 May 2010

- "How the panel voted". World Soccer. Retrieved 3 February 2018.