Orangutan

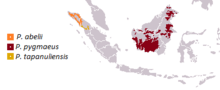

The orangutans (also spelled orang-utan, orangutang, or orang-utang) are three extant species of great apes native to Indonesia and Malaysia. Orangutans are currently only found in the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus Pongo, orangutans were originally considered to be one species. From 1996, they were divided into two species: the Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus, with three subspecies) and the Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii). In November 2017, it was reported that a third species had been identified: the Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis).

| Orangutans | |

|---|---|

| Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Ponginae |

| Genus: | Pongo Lacépède, 1799 |

| Type species | |

| Pongo borneo Lacépède, 1799 (Simia satyrus Linnaeus, 1760) | |

| Species | |

|

Pongo pygmaeus | |

| |

| Range of the three extant species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Faunus Oken, 1816 | |

Genomic comparisons show that the Tapanuli orangutan separated from the Sumatran orangutan about 3.4 million years ago. The Tapanuli orangutan separated from the Bornean orangutan much later, about 670,000 years ago. The orangutans are the only surviving species of the subfamily Ponginae, which also included several other species, such as the three extinct species of the genus Gigantopithecus, including the largest known primate, Gigantopithecus blacki. The ancestors of the Ponginae split from the main ape line in Africa 15.7 and 19.3 mya.

Orangutans are the most arboreal of the great apes and spend most of their time in trees. Their hair is reddish-brown, instead of the brown or black hair typical of chimpanzees and gorillas. Males and females differ in size and appearance. Dominant adult males have distinctive cheek pads and produce long calls that attract females and intimidate rivals. Younger males do not have these characteristics and resemble adult females. Orangutans are the most solitary of the great apes, with social bonds occurring primarily between mothers and their dependent offspring, who stay together for the first two years. Fruit is the most important component of an orangutan's diet; however, the apes will also eat vegetation, bark, honey, insects and even bird eggs. They can live over 30 years in both the wild and captivity.

Orangutans are among the most intelligent primates; they use a variety of sophisticated tools and construct elaborate sleeping nests each night from branches and foliage. The apes have been extensively studied for their learning abilities. There may even be distinctive cultures within populations. Field studies of the apes were pioneered by primatologist Birutė Galdikas. All three orangutan species are considered to be critically endangered. Human activities have caused severe declines in populations and ranges. Threats to wild orangutan populations include poaching, habitat destruction as a result of palm oil cultivation, and the illegal pet trade. Several conservation and rehabilitation organisations are dedicated to the survival of orangutans in the wild.

Etymology

The name "orangutan" (also written orang-utan, orang utan, orangutang, and ourang-outang[1]) is derived from the Malay and Indonesian words orang, meaning "man", and hutan, meaning "forest",[2] thus "man of the forest".[3]

The first attestation of the word orangutan to name the Asian ape is in Dutch physician Jacobus Bontius' 1631 Historiae naturalis et medicae Indiae orientalis – he reported that Malays had informed him the ape was able to talk, but preferred not to "lest he be compelled to labour".[4] The word appeared in several German-language descriptions of Indonesian zoology in the 17th century. The likely origin of the word comes specifically from the Banjarese variety of Malay.[5]

Cribb et al. (2014) suggest that Bontius' account referred not to apes (which were not known from Java) but rather to humans suffering some serious medical condition (most likely endemic cretinism) and that his use of the word was misunderstood by Nicolaes Tulp, who was the first to use the term in a publication.[6]

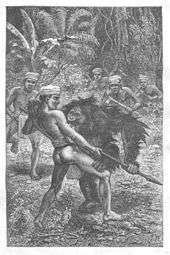

The word was first attested in English in 1691 in the form orang-outang, and variants with -ng are found in many languages. This spelling (and pronunciation) has remained in use in English up to the present, but has come to be regarded as incorrect.[7][8][9] The loss of "h" in Utan and the shift from -ng to -n has been taken to suggest that the term entered English through Portuguese.[5] In 1869, the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace published his account of Malaysia's wildlife: The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-Utan and the Bird of Paradise.[4]

The name of the genus, Pongo, comes from a 16th-century account by Andrew Battel, an English sailor held prisoner by the Portuguese in Angola, which describes two anthropoid "monsters" named Pongo and Engeco. He is now believed to have been describing gorillas, but in the 18th century, the terms orangutan and pongo were used for all great apes. Lacépède used the term Pongo for the genus following the German botanist Friedrich von Wurmb who sent a skeleton from the Indies to Europe.[10] Battel's "Pongo", in turn, is from the Kongo word mpongi[11][12] or other cognates from the region: Lumbu pungu, Vili mpungu, or Yombi yimpungu.[13]

Taxonomy, phylogeny and genetics

The three orangutan species are the only extant members of the subfamily Ponginae. This subfamily also included the extinct genera Lufengpithecus, which lived in southern China and Thailand 2–8 mya, and Sivapithecus, which lived India and Pakistan from 12.5 mya until 8.5 mya. These apes likely lived in drier and cooler environments than orangutans do today. Khoratpithecus piriyai, which lived in Thailand 5–7 mya, is believed to have been the closest known relative of the orangutans. The largest known primate, Gigantopithecus, was also a member of Ponginae and lived in China, India and Vietnam from 5 mya to 100,000 years ago.[14]:50

Within apes (superfamily Hominoidea), the gibbons diverged during the early Miocene (between 19.7 and 24.1 mya, according to molecular evidence) and the orangutans split from the African great ape lineage between 15.7 and 19.3 mya.[15](Fig. 4)

| Taxonomy of genus Pongo[16] | Phylogeny of superfamily Hominoidea[15](Fig. 4) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

History of orangutan taxonomy

The orangutan was first described scientifically in 1760 in the Systema Naturae of Linnaeus as Simia satyrus.[6] The populations on the two islands were classified as separate species when P. abelii was described by Lesson in 1827.[17] Later P. abelii was placed under P. pygmaeus, first as a synonym, then in 1985 as a subspecies.[18] In 1996, P. abelii was elevated back to full species status,[19][14]:53 and the three distinct populations on Borneo were elevated to subspecies. The population currently listed as P. p. wurmbii may be closer to the Sumatran orangutan than the other Bornean orangutan subspecies. If confirmed, abelii would be a subspecies of P. wurmbii (Tiedeman, 1808).[20]

Regardless, the type locality of P. pygmaeus has not been established beyond doubts, and may be from the population currently listed as P. wurmbii (in which case P. wurmbii would be a junior synonym of P. pygmaeus, while one of the names currently considered a junior synonym of P. pygmaeus would take precedence for the northwest Bornean taxon).[20] To further confuse, the name P. morio, as well as some suggested junior synonyms,[16] may be junior synonyms of the P. pygmaeus subspecies, thus leaving the east Bornean populations unnamed.[20]

The description in 2017 of a third species, P. tapanuliensis, from Sumatra south of Lake Toba, came with a surprising twist: it is more closely related to the Bornean species, P. pygmaeus than to its fellow Sumatran species, P. abelii.[21]

Fossil record

The oldest known record of Pongo is known from the early Pleistocene of Chongzuo, which consists of teeth found in cave deposits, with an estimated age of between 2–1 million years old, ascribed to P. weidenreichi.[22][23] Pongo is found as part of the Stegodon-Ailuropoda faunal complex in the Pleistocene cave assemblage in South China, alongside Giganopithecus, though it is only known from teeth. Some fossils described under the name P. hooijeri have been found in Vietnam, and multiple fossil subspecies have been described from several parts of southeastern Asia. It is unclear if these belong to P. pygmaeus or P. abelii or, in fact, represent distinct species.[24] During the Pleistocene, Pongo had a far more extensive range than at present, extending throughout Sundaland and mainland Southeast Asia and South China. Teeth of orangutans are known from Peninsular Malaysia that date to 60,000 years ago.[25] The range of orangutans had contracted significantly by the end of the Pleistocene, most likely due to the reduction of forest habitat during the Last Glacial Maximum.[25] though they may have survived into the Holocene in Cambodia and Vietnam.[22]

Genomics

.jpg)

The Sumatran orangutan genome was sequenced in January 2011.[26][27] Following humans and chimpanzees, the Sumatran orangutan became the third species of hominid to have its genome sequenced. Subsequently, the Bornean species had its genome sequenced. Genetic diversity was found to be lower in Bornean orangutans (P. pygmaeus) than in Sumatran ones (P. abelii), despite the fact that Borneo is home to six or seven times as many orangutans as Sumatra.[27]

The comparison has shown these two species diverged around 400,000 years ago, more recently than was previously thought. Also, the orangutan genome was found to have evolved much more slowly than chimpanzee and human DNA.[27] Previously, the species was estimated to have diverged 2.9 to 4.9 mya.[15](Fig. 4) The researchers hope these data may help conservationists save the endangered ape, and also prove useful in further understanding of human genetic diseases.[27] Of the great apes, orangutans, gorillas, and chimpanzees have 48 diploid chromosomes in contrast to humans which have 46.[28]:9

However, nuclear DNA sequence comparisons reported in 2017 suggest that Tapanuli orangutans diverged from Sumatran orangutans about 3.4 million years ago.[21][29] Tapanuli orangutans diverged from Bornean orangutans, much later, about 670,000 years ago.[21] Orangutans travelled from Sumatra to Borneo as the islands were connected by land bridges as parts of Sundaland during recent glacial periods when sea levels were much lower. The present range of Tapanuli orangutans is thought to be close to the point where ancestral orangutans first entered what is now Indonesia from mainland Asia.[21]

Anatomy and physiology

Orangutans display significant sexual dimorphism; females typically stand 115 cm (3 ft 9 in) tall and weigh around 37 kg (82 lb), while flanged adult males stand 137 cm (4 ft 6 in) tall and weigh 75 kg (165 lb). Compared to humans, they have proportionally long arms, a male orangutan having arm span of about 2 m (6.6 ft), and short legs. Most of their bodies are covered in coarse hair which is generally red but ranges from bright orange to maroon or dark chocolate, while the skin is black. Though largely hairless, their faces can develop some hair in males, giving them a moustache.[30][31][14]:14

Orangutans have small ears and noses, the former being unlobed. Females and juveniles have rounded skulls and narrow faces while males develop a large sagittal crest and large cheek flaps,[30] which show their dominance to other males. The cheek flaps are made mostly of fatty tissue and are supported by the musculature of the face.[32] Mature males also develop large throat pouches and long canines.[30][14]:14 Sumatran orangutans are thinner with paler and longer hair and longer face.[31]

As in all Old World Primates, orangutan hands are similar to human hands; they have four long fingers, but a dramatically shorter opposable thumb for strong branch gripping as they travel high in the trees. The joint and tendon arrangement in the orangutans' hands produces two adaptations that are significant for arboreal locomotion. The resting configuration of the fingers is curved, creating a suspensory hook grip. Additionally, with the thumb out of the way, the fingers (and hands) can grip securely around objects with a small diameter by resting the tops of the fingers against the inside of the palm, thus creating a double-locked grip.[33]

Their feet have four long toes and an opposable big toe, enabling orangutans to securely grasp things with both their hands and their feet. Both their fingers and toes are curved, allowing them to get a better grip on branches. Since their hip joints have the same flexibility as their shoulder and arm joints, orangutans have less restriction in the movements of their legs than humans have.[14]:14–15

Unlike gorillas and chimpanzees, orangutans are not true knuckle-walkers, but are instead fist-walkers. Knuckle-walkers use a more relaxed open hand with the middle segments of the fingers sweeping the ground while fist-walking happens with a more gripped fist so that the closest finger segments (that one might punch with) touch the ground.[34]

Ecology and behaviour

Orangutans are mainly arboreal and inhabit tropical rainforests, particularly dipterocarp and secondary old growth forest.[31][35] Population densities are highest in habitats near rivers, such as freshwater and peat swamp forests, while drier forests away from the flood plains are less inhabited. In addition, population density also decreases at higher elevations.[28]:82 Orangutans occasionally enter grasslands, cultivated fields, gardens, young secondary forest, and shallow lakes.[35]

Most of the day is spent feeding, resting, and travelling.[36] They start the day feeding for 2–3 hours in the morning. They rest during midday then travel in the late afternoon. When evening arrives, they begin to prepare their nests for the night.[35] Orangutans do not swim, although they have been recorded wading in water.[37]:80 Potential predators of orangutans include tigers, clouded leopards and wild dogs.[28]:80 The absence of tigers on Borneo has been suggested to be a reason why Bornean orangutans can be found on the ground more often than their Sumatran relatives.[31] The most frequent parasites of orangutan are nematodes of the genus Strongyloides and the ciliate Balantidium coli. Among Strongyloides, the species S. fuelleborni and S. stercoralis are commonly reported in young individuals.[38]

Diet and feeding

Orangutans are primarily frugivores (fruit-eaters) and 57–80% of their feeding time is spent foraging for fruits. Even during times of scarcity, fruit can still take up 16% of feeding. Orangutans prefer fruits which have soft pulp, arils or seed-walls surrounding their seeds, as well as fruit tree with large crops. Ficus fruits fit both preferences and are thus highly favoured but they also consume drupes and berries.[28]:47–48 Orangutans are thought to be the sole fruit disperser for some plant species including the climber species Strychnos ignatii which contains the toxic alkaloid strychnine.[39]

Orangutans also supplement their diet with leaves which take up 25% of their foraging time on average. Leaf eating increases when fruit gets scarcer but even during times of abundance, orangutan will eat leaves 11–20% of the time. The leaf and stem material of Borassodendron borneensis appears to be an important food source during low fruit abundance. Other food items consumed by the apes include bark, honey, bird eggs insects and small vertebrates including the slow loris.[35][28]:48–49

A decade-long study of urine and faecal samples at the Gunung Palung Orangutan Conservation Project in West Kalimantan has shown that orangutans give birth during and after the high fruit season (though not every year), during which they consume various abundant fruits, totalling up to 11,000 calories per day. In the low-fruit season, they eat whatever fruit is available in addition to tree bark and leaves, with daily intake at only 2,000 calories. Together with a long lactation period, orangutans also have a long birth interval.[40]

In some areas, orangutans may practice geophagy, which involves consuming soil and other earth substances. The apes may eat tubes of soil created by termites along tree trunk as well as descend to the ground to uproot soil to eat. Orangutans are also known to visit mineral licks at the clay or sandstone-like walls of cliffs or earth depressions. Soils appear to contain a high concentration of kaolin which counteracts toxic tannins and phenolic acids found in the orangutan's diet.[28]:49–50 Orangutans also use plants of the genus Commelina as an anti-inflammatory balm.[41]

Social life

Orangutans live a more solitary lifestyle than the other great apes. Most social bonds occur between adult females and their dependent and weaned offspring. Adult males and independent adolescents of both sexes tend to live alone. Orangutan societies are made up of resident and transient individuals of both sexes. Resident females live with their offspring in defined home ranges that overlap with those of other adult females, which may be their immediate relatives. One to several resident female home ranges are encompassed within the home range of a resident male, who is their main mating partner. Transient males and females move widely.[42][43] Bornean orangutans tend to be more solitary, moving and foraging alone while Sumatran orangutans travel in groups more often.[31] The social structure of the orangutan can be best described as solitary but social. Interactions between adult females range from friendly to avoidance to antagonistic.[44] Adult males dominate sub-adult males.[45]

During dispersal, females tend to settle in home ranges that overlap with their mothers. However, they do not seem to have any special social bonds with them.[43] Males disperse much farther from their mothers and enter into a transient phase. This phase lasts until a male can challenge and displace a dominant, resident male from his home range.[46] Both resident and transient orangutans aggregate on large fruiting trees to feed. The fruits tend to be abundant, so competition is low and individuals may engage in social interactions.[47][48] Orangutans will also form travelling groups with members moving between different food sources.[46] These groups tend to be made of only a few individuals. They also tend to be consortships between an adult male and female.[47]

Orangutans communicate with various sounds. Males will make long calls, both to attract females and advertise themselves to other males.[49] Long calls are divided into three parts; they begin with grumbles, climax with pulses and end with bubbles. Both sexes will try to intimidate conspecifics with a series of low guttural noises known collectively as the "rolling call". When annoyed, an orangutan will suck in air through pursed lips, making a kissing sound that is hence known as the "kiss squeak". Mothers produce throatcrapes to keep in contact with their offspring. Infants make soft hoots when distressed. Orangutans are also known to produce smacks or blow raspberries when making a nest.[50]

Nesting

Orangutans build nests specialized for both day or night use. These are carefully constructed; young orangutans learn from observing their mother's nest-building behaviour. In fact, nest-building is a leading cause in young orangutans leaving their mother for the first time. From six months of age onwards, orangutans practice nest-building and gain proficiency by the time they are three years old.[51]

Construction of a night nest is done by following a sequence of steps. Initially, a suitable tree is located, orangutans being selective about sites though many tree species are used. The nest is then built by pulling together branches under them and joining them at a point. After the foundation has been built, the orangutan bends smaller, leafy branches onto the foundation; this serves the purpose of and is termed the "mattress". After this, orangutans stand and braid the tips of branches into the mattress. Doing this increases the stability of the nest and forms the final act of nest-building. In addition, orangutans may add additional features, such as "pillows", "blankets", "roofs" and "bunk-beds" to their nests.[51]

Reproduction and development

Males become sexual mature at around 15 years of age. However, they may exhibit arrested development by not developing the distinctive cheek pads, pronounced throat pouches, long fur, or long-calls until a resident dominant male is absent. Males without then are known as unflanged males in contrast to the more developed flanged males. The transformation from unflanged to flanged can occur very quickly. Unflanged and flanged males have two different mating strategies. Flanged males attract oestrous females with their characteristic long calls which may also suppress development in younger males. Unflanged males wander widely in search of oestrous females and upon finding one, will force copulation on her. While both strategies are successful, females prefer to mate with flanged males and seek their company for protection against unflanged males. Resident males may form consortships with females that can last days, weeks or months after copulation.[52][45][49][46][14]:100

%2C_Tanjung_Putting_National_Park_01.jpg)

Female orangutans experience their first ovulatory cycle around 5.8–11.1 years. These occur earlier in females with more body fat. Like other great apes, female orangutans enter a period of infertility during adolescence which may last for 1–4 years. Female orangutans also have a 22– to 30-day menstrual cycle. Gestation lasts for 9 months, with females giving birth to their first offspring between the ages of 14 and 15 years.[53][54] Female orangutans have 6–9 year intervals between births, the longest interbirth intervals among the great apes.[55] Unlike many other primates, male orangutans do not seem to practice infanticide. This may be because they cannot ensure they will sire a female's next offspring because she does not immediately begin ovulating again after her infant dies.[56]

Male orangutans play almost no role in raising the young. Females do most of the caring and socializing of the young. A female often has an older offspring with her to help in socializing the infant.[57] Infant orangutans are completely dependent on their mothers for the first two years of their lives. The mother will carry the infant during travelling, as well as feed it and sleep with it in the same night nest.[14]:100 For the first four months, the infant is carried on its belly and never relieves physical contact. In the following months, the time an infant spends with its mother decreases.[57]

When an orangutan reaches the age of two, its climbing skills improve and it will travel through the canopy holding hands with other orangutans, a behaviour known as "buddy travel".[57] After two years of age juvenile orangutans and will start to temporarily move away from their mothers and are weaned four years old. They reach adolescence at six or seven years of age and will socialize with their peers while still having contact with their mothers.[14]:100 Typically, orangutans live for over 30 years in both the wild and captivity.[14]:14

Intelligence

Orangutans are among the most intelligent non-human primates. Experiments suggest they can figure out some invisible displacement problems with a representational strategy.[58] In addition, Zoo Atlanta has a touch-screen computer where their two Sumatran orangutans play games. Scientists hope the data they collect will help researchers learn about socialising patterns, such as whether the apes learn behaviours through trial and error or by mimicry, and point to new conservation strategies.[59]

A 2008 study of two orangutans at the Leipzig Zoo showed orangutans can use "calculated reciprocity", which involves weighing the costs and benefits of gift exchanges and keeping track of these over time. Orangutans are the first nonhuman species documented to do so.[60] Orangutans are very technically adept nest builders, making a new nest each evening in only 5 to 6 minutes and choosing branches which they know can support their body weight.[61]

Tool use and culture

Tool use in orangutans was observed by primatologist Birutė Galdikas in ex-captive populations.[62] In addition, evidence of sophisticated tool manufacture and use in the wild was reported from a population of orangutans in Suaq Balimbing (Pongo abelii) in 1996.[63] These orangutans developed a tool kit for use in foraging that consisted of both insect-extraction tools for use in the hollows of trees and seed-extraction tools for harvesting seeds from hard-husked fruit. The orangutans adjusted their tools according to the nature of the task at hand, and preference was given to oral tool use.[64] This preference was also found in an experimental study of captive orangutans (P. pygmaeus).[65]

Primatologist Carel P. van Schaik and biological anthropologist Cheryl D. Knott further investigated tool use in different wild orangutan populations. They compared geographic variations in tool use related to the processing of Neesia fruit. The orangutans of Suaq Balimbing (P. abelii) were found to be avid users of insect and seed-extraction tools when compared to other wild orangutans.[66][67] The scientists suggested these differences are cultural. The orangutans at Suaq Balimbing live in dense groups and are socially tolerant; this creates good conditions for social transmission.[66] Further evidence that highly social orangutans are more likely to exhibit cultural behaviours came from a study of leaf-carrying behaviours of ex-captive orangutans that were being rehabilitated on the island of Kaja in Borneo.[68]

Wild orangutans (P. pygmaeus wurmbii) in Tuanan, Borneo, were reported to use tools in acoustic communication. They use leaves to amplify the kiss squeak sounds they produce. The apes may employ this method of amplification to deceive the listener into believing they are larger animals.[69]

In 2003, researchers from six different orangutan field sites who used the same behavioural coding scheme compared the behaviours of the animals from the different sites. They found the different orangutan populations behaved differently. The evidence suggested the differences were cultural: first, the extent of the differences increased with distance, suggesting cultural diffusion was occurring, and second, the size of the orangutans' cultural repertoire increased according to the amount of social contact present within the group. Social contact facilitates cultural transmission.[70]

Possible linguistic capabilities

A study of orangutan symbolic capability was conducted from 1973 to 1975 by zoologist Gary L. Shapiro with Aazk, a juvenile female orangutan at the Fresno City Zoo (now Chaffee Zoo) in Fresno, California. The study employed the techniques of psychologist David Premack, who used plastic tokens to teach linguistic skills to the chimpanzee, Sarah.[71] Shapiro continued to examine the linguistic and learning abilities of ex-captive orangutans in Tanjung Puting National Park, in Indonesian Borneo, between 1978 and 1980.[72]

During that time, Shapiro instructed ex-captive orangutans in the acquisition and use of signs following the techniques of psychologists R. Allen Gardner and Beatrix Gardner, who taught the chimpanzee, Washoe, in the late 1960s. In the only signing study ever conducted in a great ape's natural environment, Shapiro home-reared Princess, a juvenile female, which learned nearly 40 signs (according to the criteria of sign acquisition used by psychologist Francine Patterson with Koko, the gorilla) and trained Rinnie, a free-ranging adult female orangutan, which learned nearly 30 signs over a two-year period.[72] For his dissertation study, Shapiro examined the factors influencing sign learning by four juvenile orangutans over a 15-month period.[73]

Orangutans and humans

Orangutans were known to the native people of Sumatra and Borneo for millennia. While some communities hunted them for food and decoration, others placed taboos on such practices.[14]:66 In central Borneo, some traditional folk beliefs consider it bad luck to look in the face of an orangutan. Some folk tales involve orangutans mating with and kidnapping humans.[14]:68 There are even stories of hunters being seduced by female orangutans.[14]:71

Europeans became aware of the existence of the orangutan possibly as early as the 17th century.[14]:68 European explorers in Borneo hunted them extensively during the 19th century.[14]:65 The first accurate description of orangutans was given by Dutch anatomist Petrus Camper, who observed the animals and dissected some specimens.[14]:64 Little was known about their behaviour until the field studies of Birutė Galdikas,[74] who became a leading authority on the apes.[75] When she arrived in Borneo, Galdikas settled into a primitive bark and thatch hut, at a site she dubbed Camp Leakey, near the edge of the Java Sea.[75] Despite numerous hardships, she remained there for over 30 years and became an outspoken advocate for orangutans and the preservation of their rainforest habitat, which is rapidly being devastated by loggers, palm oil plantations, gold miners, and unnatural forest fires.[76] Galdikas's conservation efforts have extended well beyond advocacy, largely focusing on rehabilitation of the many orphaned orangutans turned over to her for care.[75] Galdikas is considered to be one of Leakey's Angels, along with Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey.[77]

A persistent folktale on Sumatra and Borneo and in popular culture, is that male orangutans display sexual attraction to human women, and may even forcibly copulate with them.[78] The only serious, but anecdotal, report of such an incident taking place, is a report from Galdikas that her cook was sexually assaulted by a male orangutan.[79] This orangutan, though, was raised in captivity and may have suffered from a skewed species identity, and forced copulation is a standard mating strategy for low-ranking male orangutans.[78]

Legal status

In December 2014, Argentina became the first country to recognise a non-human primate as having legal rights when it ruled that an orangutan named Sandra at the Buenos Aires Zoo must be moved to a sanctuary in Brazil in order to provide her "partial or controlled freedom". Animal rights groups like Great Ape Project Argentina interpreted the ruling as applicable to all species in captivity, and legal specialists from the Argentina's Federal Chamber of Criminal Cassatio considered the ruling only applicable to non-human hominids.[80]

Conservation

Conservation status

The Sumatran and Bornean species are both critically endangered[82][83] according to the IUCN Red List of mammals, and both are listed on Appendix I of CITES.[82][83] The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimated in 2016 that around 100,000 orangutans survive in the wild (in 1973 there were 288,500), and their population is expected to further decrease to as few as 47,000 individuals by 2025.[84]

The Bornean orangutan population declined by 60% in the past 60 years and is projected to decline by 82% over 75 years. Its range has become patchy throughout Borneo, being largely extirpated from various parts of the island, including the southeast.[83] The largest remaining population is found in the forest around the Sabangau River, but this environment is at risk.[85]

Sumatran orangutan populations declined by 80% in 75 years.[82] This species is now found only in the northern part of Sumatra, with most of the population inhabiting the Leuser Ecosystem.[82] In late March 2012, a once-significant population in northern Sumatra were reported to be threatened with approaching forest fires and might be wiped out entirely within a matter of weeks.[86]

Estimates between 2000 and 2003 found 7,300 Sumatran orangutans[82] and between 45,000 and 69,000 Bornean orangutans[83] remain in the wild. A 2007 study by the Government of Indonesia noted a total wild population of 61,234 orangutans, 54,567 of which were found on the island of Borneo in 2004. The table below shows a breakdown of the species and subspecies and their estimated populations from this, or (in the case of P. tapanuliensis) a more recent, report:[87][88]

| Scientific name |

Common name |

Region | Estimated number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pongo abelii | Sumatran orangutan | Sumatra | 6,667 |

| Pongo tapanuliensis | Tapanuli orangutan | Sumatra (Lake Toba region) | <800 |

| Pongo pygmaeus | Bornean orangutan | Borneo | |

| P. p. morio | Northeast Bornean orangutan | Sabah | 11,017 |

| East Kalimantan | 4,825 | ||

| P. p. wurmbii | Central Bornean orangutan | Central Kalimantan | >31,300 |

| P. p. pygmaeus | Northwest Bornean orangutan | West Kalimantan and Sarawak | 7,425 |

During the early 2000s, orangutan habitat has decreased rapidly due to logging and forest fires, as well as fragmentation by roads.[82][83] A major factor in that period of time has been the conversion of vast areas of tropical forest to palm oil plantations in response to international demand. Palm oil is used for cooking, cosmetics, mechanics, and biodiesel.[83] Hunting is also a major problem[82][83] as is the illegal pet trade.[82][83]

Orangutans may be killed for the bushmeat trade, crop protection, or for use for traditional medicine. Orangutan bones are secretly traded in souvenir shops in several cities in Kalimantan, Indonesia.[89] Mother orangutans are killed so their infants can be sold as pets, and many of these infants die without the help of their mother.[90] Since 2004, several pet orangutans were confiscated by local authorities and sent to rehabilitation centres.[83]

A female orangutan was rescued from a village brothel in Kareng Pangi village, Central Kalimantan, in 2003.[91][92] The orangutan was shaved and chained for sexual purposes.[92][93] Since being freed, the orangutan, named Pony, has been living with the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation.[91] She has been re-socialised to live with other orangutans.[91] In May 2017, a group of activists of the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation (BOSF) rescued an albino organgutan from captivity in a remote village in Borneo. According to volunteers at BOSF, albino orangutans are extremely rare – 1 out of 10,000 individuals. It was the first albino orangutan the organisation had seen in 25 years of activity.[84][94]

In November 2017, researchers found genomic evidence for a new species of orangutan named, Pongo tapanuliensis, found only in the Batang Toru forest of Sumatra, Indonesia. It is estimated that fewer than 800 individuals still exist, which puts the Tapanuli orangutan among the most endangered of great apes.[95][96]

Conservation centres and organisations

A number of organisations are working for the rescue, rehabilitation and reintroduction of orangutans. The largest of these is the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, founded by conservationist Willie Smits. It is audited by a multinational auditor company[97] and operates a number of large projects, such as the Nyaru Menteng Rehabilitation Program founded by conservationist Lone Drøscher Nielsen.[98][99]

Other major conservation centres in Indonesia include those at Tanjung Puting National Park and Sebangau National Park in Central Kalimantan, Kutai in East Kalimantan, Gunung Palung National Park in West Kalimantan, and Bukit Lawang in the Gunung Leuser National Park on the border of Aceh and North Sumatra. In Malaysia, conservation areas include Semenggoh Wildlife Centre in Sarawak and Matang Wildlife Centre also in Sarawak, and the Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary near Sandakan in Sabah.[100] Major conservation centres that are headquartered outside of the orangutan's home countries; include Frankfurt Zoological Society, Orangutan Foundation International, which was founded by Birutė Galdikas,[101] and the Australian Orangutan Project.[102]

Conservation organisations such as Orangutan Land Trust work with the palm oil industry to improve sustainability and encourages the industry to establish conservation areas for orangutans.[103] It works to bring different stakeholders together to achieve conservation of the species and its habitat.[104]

See also

- Monkey Day

- The Librarian

References

- "orangutan: definition of orangutan in Oxford dictionary (British & World English)". Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Harper, Douglas. ""Orangutan" entry in Etymology Online". Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Orangutan". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Dellios, Paulette (2008). "A lexical odyssey from the Malay World". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 23 (1).

- Mahdi, Waruno (2007). Malay words and Malay things: lexical souvenirs from an exotic archipelago in German publications before 1700. Frankfurter Forschungen zu Südostasien. 3. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 170–181. ISBN 978-3-447-05492-8.

- Cribb, Robert; Helen Gilbert & Helen Tiffin (2014). Wild Man from Borneo: a cultural history of the orangutan. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3714-3.

- "Orangutan". alphadictionary.com. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Peter Tan (October 1998). "Malay loan words across different dialects of English". English Today. 14 (4): 44–50. doi:10.1017/S026607840001052X.

- Cannon, Garland (1992). "Malay(sian) borrowings in English". American Speech. 67 (2): 134–162. doi:10.2307/455451. JSTOR 455451.

- Groves, Colin P. (2002). "A history of gorilla taxonomy" (PDF). In Taylor, Andrea B.; Goldsmith, Michele L. (eds.). Gorilla Biology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–34. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511542558.004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009.

- "pongo". Etymology Online. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "pongo". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "pongo, n.1". OED Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- Payne, J; Prundente, C (2008). Orangutans: Behavior, Ecology and Conservation. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-0-262-16253-1.

- Israfil, H.; Zehr, S. M.; Mootnick, A. R.; Ruvolo, M.; Steiper, M. E. (2011). "Unresolved molecular phylogenies of gibbons and siamangs (Family: Hylobatidae) based on mitochondrial, Y-linked, and X-linked loci indicate a rapid Miocene radiation or sudden vicariance event" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 58 (3): 447–455. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.005. PMC 3046308. PMID 21074627. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2012.

- Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Lesson, René-Primevère (1827). Manuel de mammalogie ou Histoire naturelle des mammifères (in French). Paris: Roret, Libraire. p. 32.

- Groves, C. P.; Holthuis, L. B. (31 December 1985). "The nomenclature of the Orang Utan". Zoologische Mededelingen. 59 (31): 411–417. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Xu, X.; Arnason, U. (1996). "The mitochondrial DNA molecule of sumatran orangutan and a molecular proposal for two (Bornean and Sumatran) species of orangutan". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 43 (5): 431–437. Bibcode:1996JMolE..43..431X. doi:10.1007/BF02337514. PMID 8875856.

- Bradon-Jones, D.; Eudey, A. A.; Geissmann, T.; Groves, C. P.; Melnick, D. J.; Morales, J. C.; Shekelle, M.; Stewart, C. B. (2004). "Asian primate classification" (PDF). International Journal of Primatology. 25: 97–164. doi:10.1023/B:IJOP.0000014647.18720.32.

- Nater, A.; Mattle-Greminger, M. P.; Nurcahyo, A.; Nowak, M. G.; et al. (2 November 2017). "Morphometric, Behavioral, and Genomic Evidence for a New Orangutan Species". Current Biology. 27 (22): 3487–3498.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.047. PMID 29103940.

- Harrison, Terry; Jin, Changzhu; Zhang, Yingqi; Wang, Yuan; Zhu, Min (December 2014). "Fossil Pongo from the Early Pleistocene Gigantopithecus fauna of Chongzuo, Guangxi, southern China". Quaternary International. 354: 59–67. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.01.013.

- Wang, Cui-Bin; Zhao, Ling-Xia; Jin, Chang-Zhu; Wang, Yuan; Qin, Da-Gong; Pan, Wen-Shi (December 2014). "New discovery of Early Pleistocene orangutan fossils from Sanhe Cave in Chongzuo, Guangxi, southern China". Quaternary International. 354: 68–74. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.06.020.

- Schwartz, J.H.; Vu The Long; Nguyen Lan Cuong; Le Trung Kha; Tattersall, I. (1995). "A review of the Pleistocene hominoid fauna of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (excluding Hylobatidae)". Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History (76): 1–24. hdl:2246/259.

- Ibrahim, Yasamin Kh.; Tshen, Lim Tze; Westaway, Kira E.; Cranbrook, Earl of; Humphrey, Louise; Muhammad, Ros Fatihah; Zhao, Jian-xin; Peng, Lee Chai (December 2013). "First discovery of Pleistocene orangutan (Pongo sp.) fossils in Peninsular Malaysia: Biogeographic and paleoenvironmental implications". Journal of Human Evolution. 65 (6): 770–797. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.005. PMID 24210657.

- Locke, D. P.; Hillier, L. W.; Warren, W. C.; Worley, K. C.; Nazareth, L. V.; Muzny, D. M.; Yang, S. P.; Wang, Z.; Chinwalla, A. T.; Minx, P.; Mitreva, M.; Cook, L.; Delehaunty, K. D.; Fronick, C.; Schmidt, H.; Fulton, L. A.; Fulton, R. S.; Nelson, J. O.; Magrini, V.; Pohl, C.; Graves, T. A.; Markovic, C.; Cree, A.; Dinh, H. H.; Hume, J.; Kovar, C. L.; Fowler, G. R.; Lunter, G.; Meader, S.; et al. (2011). "Comparative and demographic analysis of orang-utan genomes". Nature. 469 (7331): 529–533. Bibcode:2011Natur.469..529L. doi:10.1038/nature09687. PMC 3060778. PMID 21270892.

- Singh, Ranjeet (4 January 2011). "Orang-utans join the genome gang". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.50. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Rijksen H. D.; Meijaard, E. (1999). Our vanishing relative: the status of wild orang-utans at the close of the twentieth century. Springer. ISBN 978-0792357551.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Wright, Stephen (2 November 2017). "Frizzy-haired, smaller-headed orangutan may be new great ape". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Groves, Colin P. (1971). "Pongo pygmaeus". Mammalian Species. 4 (4): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503852. JSTOR 3503852.

- van Schaik, C.; MacKinnon, J. (2001). "Orangutans". In MacDonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 420–23. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- Winkler, L. A. (1989). "Morphology and relationships of the orangutan fatty cheek pads". American Journal of Primatology. 17 (4): 305–19. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350170405. PMID 31964053.

- Rose, M. D. (1988). "Functional Anatomy of the Cheirdia". In Schwartz, Jeffrey (ed.). Orang-utan Biology. Oxford University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-19-504371-6.

- Schwartz, Jeffrey (1987). The Red Ape: Orangutans and Human Origins. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-8133-4064-7.

- Galdikas, Birute M.F. (1988). "Orangutan Diet, Range, and Activity at Tanjung Puting, Central Borneo". International Journal of Primatology. 9 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1007/BF02740195.

- Rodman, P. S. (1988). "Diversity and consistency in ecology and behavior". In Schwartz, J. H. (ed.). Orang-utan biology. pp. 31–51. ISBN 9780195043716.

- Kuliukas, A. (2001). Bipedal Wading in Hominoidae past and present (PDF) (Master of Science thesis). University College London.

- Foitová, F.; et al. "Parasites and their impacts on orangutan health". In Wich, S. A.; Atmoko, S. S. U.; Setia, T. M.; van Schaik, C. P. (ed.). Orangutans: Geographic Variation in Behavioral Ecology and Conservation. Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0199213276.CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- Rijksen, H. D. (December 1978). "A field study on Sumatran orang utans (Pongo pygmaeus abelii, Lesson 1827): Ecology, Behaviour and Conservation". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 53 (4): 493–494. doi:10.1086/410942. JSTOR 2826733.

- Asrianti, Tifa (4 July 2011). "For orangutans, less food means lowered fertility". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Morrogh-Bernard, H. C. (2008). "Fur-Rubbing as a Form of Self-Medication in Pongo pygmaeus". International Journal of Primatology. 29 (4): 1059–1064. doi:10.1007/s10764-008-9266-5.

- Teboekhorst, I; Schürmann, C; Sugardjito, J (1990). "Residential status and seasonal movements of wild orang-utans in the Gunung Leuser Reserve (Sumatera, Indonesia)". Animal Behaviour. 39 (6): 1098–1109. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80782-1.

- Singleton, I; van Schaik, CP (2002). "The Social Organisation of a population of Sumatran orang-utans". Folia Primatol. 73 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1159/000060415. PMID 12065937.

- Galdikas, B. M. F. (1984). "Adult female sociality among wild orangutans at Tanjung Puting Reserve". In Small, M. F. (ed.). Female primates: studies by women primatologists. Alan R. Liss. pp. 217–35. ISBN 978-0845134030.

- Fox, EA. (2002). "Female tactics to reduce sexual harassment in the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus abelii)". Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 52 (2): 93–101. doi:10.1007/s00265-002-0495-x.

- Delgado, RA Jr.; van Schaik, CP (2000). "The behavioral ecology and conservation of the orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus): a tale of two islands". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 9 (1): 201–18. doi:10.1002/1520-6505(2000)9:5<201::AID-EVAN2>3.0.CO;2-Y.

- van Schaik, C. P.; Preuschoft, S.; Watts, D. P. (2004). "Great ape social systems". In Russon, A. E.; Begun, D. R. (ed.). The evolution of thought: evolutionary origins of great ape intelligence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 190–209. ISBN 978-0521039925.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- van Schaik, C. P. (1999). "The socioecology of fission-fusion sociality in orangutans". Primates. 40 (1): 69–86. doi:10.1007/BF02557703.

- Utami, SS; Goossens, B; Bruford, MW; de Ruiter, JR; van Hooff, JARAM (2002). "Male bimaturism and reproductive success in Sumatran orangutans". Behav Ecol. 13 (5): 643–52. doi:10.1093/beheco/13.5.643.

- "Orangutan call repertoires". Universität Zürich - Department of Anthropology. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- Didik, Prasetyo; Ancrenaz, Marc; Morrogh-Bernard, Helen C.; Atmoko, S. Suci Utami; Wich, Serge A. & van Schaik, Carel P. (2009). "Nest building in orangutans". In Wich, Serge A.; Atmoko, S. Suci Utami & Setia, Tatang Mitra (eds.). Orangutans: geographic variation in behavioral ecology and conservation. Oxford University Press. pp. 270–275. ISBN 978-0-19-921327-6.

- Schürmann, CL; Hooff, JARAM (1986). "Reproductive strategies of the orangutan: new data and a reconsideration of existing sociosexual models". Int J Primatol. 7 (3): 265–87. doi:10.1007/BF02736392.

- Knott, C. (2001). "Female reproductive ecology of the apes: implications for human evolution". In Ellison P. T. (ed.). Reproductive ecology and human evolution. Aldine de Gruyter. pp. 429–63. ISBN 978-0202306575.

- Galdikas, B. M. F. (1995). "Social and reproductive behavior of wild adolescent female orangutans". In Nadler, R. D.; Galdikas, B. F, M.; Sheeran, L. K.; Rosen, N. (ed.). The neglected ape. Springer. p. 163–82. ISBN 978-1489910936.CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- Wich, S. A.; et al. "Orangutan life history variation". In Wich, S. A.; Atmoko, S. S. U.; Setia, T. M.; van Schaik, C. P. (ed.). Orangutans: Geographic Variation in Behavioral Ecology and Conservation. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0199213276.CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- Beaudrot, LH; Kahlenberg, SM; Marshall, AJ (2009). "Why male orangutans do not kill infants". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 63 (11): 1549–1562. doi:10.1007/s00265-009-0827-1. PMC 2728907. PMID 19701484.

- Munn C; Fernandez M (1997). "Infant development". In Carol Sodaro (ed.). Orangutan species survival plan husbandry manual. Chicago: Chicago Zoological Park. pp. 59–66. OCLC 40349739.

- Deaner, RO; van Schaik, CP; Johnson, V. (2006). "Do some taxa have better domain-general cognition than others? A meta-analysis of nonhuman primate studies" (PDF). Evol Psych. 4: 149–196.

- Turner, Dorie (12 April 2007). "Orangutans play video games (for research) at Georgia zoo". Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- Dufour, V.; Pelé, M.; Neumann, M.; Thierry, B.; Call, J. (2008). "Calculated reciprocity after all: computation behind token transfers in orang-utans". Biol. Lett. 5 (2): 172–75. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0644. PMC 2665816. PMID 19126529.

- "Orangutan Sangat Cerdas Soal Konstruksi". 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- Galdikas, BMF (1982). "Orang-Utan tool use at Tanjung Putting Reserve, Central Indonesian Borneo (Kalimantan Tengah)". Journal of Human Evolution. 10: 19–33. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(82)80028-6.

- van Schaik, CP; Fox, EA; Sitompul, AF. (1996). "Manufacture and use of tools in wild Sumatran orangutans – implications or human evolution". Naturwissenschaften. 83 (4): 186–188. doi:10.1007/BF01143062. PMID 8643126.

- Fox EA, Sitompul AF, van Schaik CP. (1999). "Intelligent tool use in wild Sumatran orangutans". In: Parker S, Mitchell RW and Miles HL (eds.) The Mentality of Gorillas and Orangutans. Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–116, ISBN 978-0-521-03193-6.

- O'Malley, RC; McGrew, WC. (2000). "Oral tool use by captive orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus)". Folia Primatol. 71 (5): 334–341. doi:10.1159/000021756. PMID 11093037.

- van Schaik, Carel P.; Knott, Cheryl D. (2001). "Geographic variation in tool use onNeesia fruits in orangutans". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 114 (4): 331–342. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1045. PMID 11275962.

- van Schaik, CP; Van Noordwijk, MA; Wich, SA. (2006). "Innovation in wild Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii)". Behaviour. 143 (7): 839–876. doi:10.1163/156853906778017944.

- Russon, AE; Handayani, DP; Kuncoro, P; Ferisa, A. (2007). "Orangutan leaf-carrying for nest-building: toward unraveling cultural processes". Animal Cognition. 10 (2): 189–202. doi:10.1007/s10071-006-0058-z. PMID 17160669.

- Hardus, ME; Lameira, AR; van Schaik, CP; Wich, SA. (2009). "Tool use in wild orang-utans modifies sound production: a functionally deceptive innovation?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1673): 3689–3694. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1027. PMC 2817314. PMID 19656794.

- van Schaik, CP; Ancrenaz, M; Borgen, G; Galdikas, B; Knott, CD; Singleton, I; Suzuki, A; Utami, SS; Merrill, M.; et al. (2003). "Orangutan cultures and the evolution of material culture". Science. 299 (5603): 102–105. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..102V. doi:10.1126/science.1078004. PMID 12511649.

- Shapiro, G. L. (1975). Teaching linguistics concepts to a juvenile orangutan. California State University. Unpublished Masters Thesis.

- Shapiro, G. L. (1982). "Sign acquisition in a home-reared/free-ranging orangutan: Comparisons with other signing apes". American Journal of Primatology. 3 (1–4): 121–29. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350030111. PMID 31991986.

- Shapiro, G. L. (1985). Factors influencing the variance in sign learning performance by four juvenile orangutans (PDF) (Thesis). University of Oklahoma.

- de Waal, Frans (January 1995). "The Loneliest of Apes". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Galdikas-Brindamour, Birutė (October 1975). "Orangutans, Indonesia's "People of the Forest"". National Geographic Magazine. 148 (4). pp. 444–473.

- Robin McDowell (18 January 2009). "Palm oil frenzy threatens to wipe out orangutans". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 20 January 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- MacClancy, J.; Fuentes, A. (2010). Centralizing Fieldwork: Critical Perspectives from Primatology, Biological, and Social Anthropology. Berghahn Books. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-84545-690-0.

- van Schaik, Carel (2004). Among Orangutans: Red Apes and the Rise of Human Culture. Harvard University Press. p. 88.

- Wrangham, Richard W; Peterson, Dale (1996). Demonic males : apes and the origins of human violence. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-395-69001-7.

- Emiliano Giménez (23 December 2014). "Argentine orangutan granted unprecedented legal rights".

- Riskanalys av glas, järn, betong och gips 29 March 2011. s.19–20 (in Swedish)

- Singleton, I.; Wich, S.A. & Griffiths, M. (2008). "Pongo abelii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ancrenaz, M.; Gumal, M.; Marshall, A.J.; Meijaard, E.; Wich, S.A. & Husson, S. (2016). "Pongo pygmaeus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T17975A17966347. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T17975A17966347.en.

- Brenna, Lorenzo. "Lifegate".

- Cheyne, S. M.; Thompson, C. J.; Phillips, A. C.; Hill, R. M.; Limin, S. H. (2007). "Density and population estimate of gibbons (Hylobates albibarbis) in the Sabangau catchment, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia". Primates. 49 (1): 50–56. doi:10.1007/s10329-007-0063-0. PMID 17899314.

- "Fires threaten Sumatran orangutans". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- "Orangutan Action Plan 2007–2017" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Government of Indonesia. 2007. p. 5. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Gill, Victoria (2 November 2017). "New great ape species identified". BBC News.

- "Stop orangutan skull trade". antaranews.com. 7 September 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Patricia L. Miller-Schroeder (2004). Orangutans. The Untamed World. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-55388-049-3. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- "Pony's New Life – BOS Foundation".

- "The Horrifying Story of a Sex Slave Orangutan".

- "Orang-utan rescue in the heart of Borneo". Worldwide Wildlife Fund. 2005.

- "National Geographic".

- Nater, Alexander; Mattle-Greminger, Maja P.; Nurcahyo, Anton; Nowak, Matthew G.; Manuel, Marc de; Desai, Tariq; Groves, Colin; Pybus, Marc; Sonay, Tugce Bilgin (2 November 2017). "Morphometric, Behavioral, and Genomic Evidence for a New Orangutan Species". Current Biology. 0 (22): 3487–3498.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.047. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 29103940.

- Reese, April (2 November 2017). "Newly discovered orangutan species is also the most endangered". Nature News. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "About BOS Foundation". Samboja lodge. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- "10 Years: Nyaru Menteng 1999–2009" (PDF). Orangutan Protection Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2010.

- "Ny projektledare på Nyaru Menteng". savetheorangutan.se. 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- "Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary". Tourism Malaysia. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- Martinelli, D. (2010). A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics: People, Paths, Ideas. Springer. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-90-481-9248-9.

- "Tax Deductible Organisations (Register of Environmental Organisations)". Australian Department of the Environment and Water Resources. Archived from the original on 10 February 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- Butler, R.A. (20 August 2009). "Rehabilitation not enough to solve orangutan crisis in Indonesia". mongabay.com.

- Marusiak, J. (28 June 2011). "New deal for orangutans in Kalimantan". Eco-Business.com.

Further reading

- Vltchek, Andre (3 June 2017). Indonesian Borneo is Finished: They Also Sell Orangutans into Sex Slavery.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pongo. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Pongo |

| Look up orangutan in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |