Okinawa Island

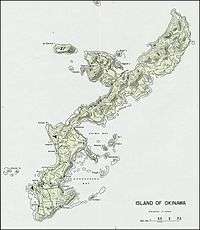

Okinawa Island (沖縄本島, Okinawa-hontō, alternatively 沖縄島 Okinawa-jima; Okinawan: 沖縄/うちなー Uchinaa or 地下/じじ jiji;[4] Kunigami: ふちなー Fuchináa) is the largest of the Okinawa Islands and the Ryukyu (Nansei) Islands of Japan in the Kyushu region. It is the smallest and least populated of the five main islands of Japan.[5] The island is approximately 66 miles (106 km) long and an average 7 miles (11 km) wide,[6] and has an area of 1,206.98 square kilometers (466.02 sq mi). It is roughly 640 kilometres (400 mi) south of the main island of Kyushu and the rest of Japan. It is 500 km (300 mi) north of Taiwan. The total population of Okinawa Island is 1,384,762.[3] The Greater Naha area has roughly 800,000 residents while the city itself has about 320,000 people. Naha is home to the prefectural seat of Okinawa Prefecture on the southwestern part of Okinawa Island. It has a humid subtropical climate. Okinawa is part of the Kyushu region.

| Native name: 沖縄本島 | |

|---|---|

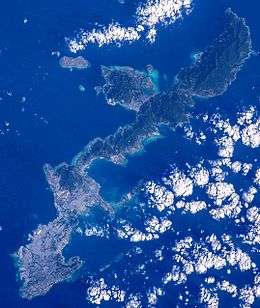

Okinawa Island in 2015 | |

Okinawa Island | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 26°28′46″N 127°55′40″E |

| Archipelago | Ryukyu Islands |

| Area | 1,199[1] km2 (463 sq mi) as of 1 October 2018[2] |

| Area rank | 290th |

| Length | 106.6 km (66.24 mi) |

| Width | 11.3 km (7.02 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 503 m (1,650 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Yonaha |

| Administration | |

| Prefecture | Okinawa Prefecture |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1,384,762 [3] (2009) |

| Pop. density | 1,014.93/km2 (2,628.66/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Okinawan (Ryukyuan), Japanese |

Okinawa has been a critical strategic location for the United States Armed Forces since the end of World War II. The island hosts around 26,000 US military personnel, about half of the total complement of the United States Forces Japan, spread among 32 bases and 48 training sites.

History

| History of Ryukyu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Periods

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Topics

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early Okinawan history is defined by midden or shell heap culture, and is divided into Early, Middle, and Late Shell Mound periods. The Early Shell Mound period was a hunter-gatherer society, with wave-like opening Jōmon pottery. In the latter part of this period, archaeological sites moved near the seashore, suggesting the engagement of people in fishing. On Okinawa, rice was not cultivated until the Middle Shell Mound period. Shell rings for arms made of shells obtained in the Sakishima Islands, namely Miyakojima and Yaeyama islands, were imported by Japan. In these islands, the presence of shell axes, 2500 years ago, suggests the influence of a southeastern-Pacific culture.[7][8]

After the Late Shell Mound period, agriculture started about the 12th century, with the center moving from the seashore to higher places. This period is called the Gusuku period. Gusuku is the term used for the distinctive Ryukyuan form of castles or fortresses. Many gusukus and related cultural remains in the Ryukyu Islands have been listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites under the title Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu. There are three perspectives regarding the nature of gusukus: 1) a holy place, 2) dwellings encircled by stones, 3) a castle of a leader of people. In this period, porcelain trade between Okinawa and other countries became busy, and Okinawa became an important relay point in eastern-Asian trade. Ryukyuan kings, such as Shunten and Eiso, were important rulers. An attempted Mongolian invasion in 1291 during the Eiso Dynasty ended in failure. Hiragana was imported from Japan by Ganjin in 1265. Noro, village priestesses of the Ryukyuan religion, appeared.

The Sanzan period began in 1314, when the kingdoms of Hokuzan and Nanzan declared independence from Chūzan. The three kingdoms competed with one another for recognition and trade with Ming China. King Satto, leading Chūzan, was very successful, establishing relations with Korea and Southeast Asia as well as China. The Hongwu Emperor sent 36 families from Fujian in 1392 at the request of the Ryukyuan King. Their job was to manage maritime dealings in the kingdom. They assisted the Ryukyuans in developing their technology and diplomatic relations. In 1407, however, a man named Hashi overthrew Satto's descendant, King Bunei, and installed his own father, Shishō, as king of Chūzan.

In 1429, King Shō Hashi completed the unification of the three kingdoms and founded the Ryūkyū Kingdom with its capital at Shuri Castle. His descendants would conquer the Amami Islands. In 1469, King Shō Taikyū died, so the royal government chose a man named Kanemaru as the new king, who chose the name Shō En and established the Second Shō Dynasty. His son, Shō Shin would then conquer the Sakishima Islands and centralize the royal government, the military, and the noro priestesses.

In 1609, the Japanese domain of Satsuma launched an invasion of the Ryukyu Kingdom, ultimately capturing the king and his capital after a long struggle. Ryukyu was forced to cede the Amami Islands and become a vassal of Satsuma. The kingdom became both a tributary of China and a tributary of Japan. Because China would not make a formal trade agreement unless a country was a tributary state, the kingdom was a convenient loophole for Japanese trade with China. When Japan officially closed off trade with European nations except the Dutch, Nagasaki, Tsushima, and Kagoshima became the only Japanese trading ports offering connections with the outside world.

A number of Europeans visited Ryukyu starting in the late 18th century. The most important visits to Okinawa were from Captain Basil Chamberlain in 1816 and Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1852. A Christian missionary, Bernard Jean Bettelheim, lived in the Gokoku-ji temple in Naha from 1846 to 1854.

In 1879, Japan annexed the entire Ryukyu archipelago.[9] The Meiji government then established Okinawa Prefecture. The monarchy in Shuri was abolished and the deposed king Shō Tai (1843–1901) was forced to relocate to Tokyo.

.jpg)

Hostility against Japan increased in the islands immediately after the annexation in part because of the systematic attempt on the part of Japan to eliminate Ryukyuan culture, including the language, religion, and cultural practices.

Okinawa Island had the bloodiest ground battle of the Pacific War from April 1, 1945 to June 22, 1945. During this 82-day-long battle, about 95,000 Imperial Japanese Army troops and 20,195 Americans were killed. The Cornerstone of Peace at the Peace Memorial Park in Itoman lists 149,193 persons from Okinawa – approximately one quarter of the civilian population – were either killed or committed suicide during the Battle of Okinawa and the Pacific War.[10] Very few Japanese ended up in POW camps. This may have been due to Japanese soldiers' reluctance to surrender. The total number of casualties shocked American military strategists. This made them apprehensive to invade the other main islands of Japan, because it would result in very high casualties.[11][12][13]

Japan became a pacifist country with the 1947 constitution. So America was obligated to protect Japan against foreign threats. During the American military occupation of Japan (1945–52), which followed the Imperial Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945, in Tokyo Bay, the United States controlled Okinawa Island and the rest of the Ryukyu Islands. The Amami Islands were returned to Japanese control in 1953. The remaining Ryukyu Islands were returned to Japan on June 17, 1972. America kept numerous U.S. military bases on the islands. There are 32 United States military bases on Okinawa Island [14] in accordance with the U.S.-Japan alliance since 1951. US bases on Okinawa played critical roles in the Korean War, Vietnam War, War in Afghanistan, and Iraq War.

In 2013, following escalating tensions following competing claims to the uninhabited Senkaku Islands, the People's Republic of China began laying claims to the island of Okinawa.[15][16]

On 31 October 2019, the main courtyard structures of Shurijo were destroyed in a fire.[17] This is the fifth time that Shurijo was destroyed following previous incidents in 1453, 1660, 1709 and 1945.[18]

Demographics

As of September, 2009, the Japanese government estimates the population at 1,384,762,[3] which includes American military personnel and their families. The Okinawan language, called Uchinaaguchi, is spoken mostly by the elderly.[19] But several local groups promote the use of the Okinawan language by younger people.[20]

Whereas the northern half of Okinawa Island is sparsely populated, the south-central and southern parts of the island are markedly urbanized—particularly the city of Naha and the urban corridor stretching north from there to Okinawa City. The population distribution is approximately 120,000 in Northern Okinawa, 590,000 in Central Okinawa and 540,000 in Southern Okinawa. It has a high population density of 1,014.93 people per km2.[21]

Since 1609 when the Ryukyu islands became a vassal of the Satsuma Domain, there has been major migration of Japanese to Okinawa. The modern inhabitants of Okinawa are mainly ethnic Okinawan, Japanese, half Japanese and mixed.

Five times as many Okinawans become 100 years old compared to the rest of Japan. The Okinawan diet consist of low-fat, low-salt foods, such as whole fruits and vegetables, legumes, tofu, and seaweed. Okinawans are known for their longevity. This particular island is a so-called Blue Zone, an area where the people live longer than most others elsewhere in the world.[22] As of 2002 there were 34.7 centenarians for every 100,000 inhabitants, which is the highest ratio worldwide.[23]:131–132 Possible explanations are diet, low-stress lifestyle, caring community, activity, and spirituality of the inhabitants of the island.[23]

Geography

Okinawa is the fifth largest island of Japan. The island has an area of 1,206.99 square kilometers (466.02 sq mi). The coastline is 476 kilometers (296 mi) long.[24] The straight-line distance is about 106.6 kilometers (66.2 mi) from north to south.[25] Okinawa is in the northeastern end of Okinawa Prefecture. Since 1972 over 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres) of land reclamation was conducted.

It is roughly 640 kilometres (400 mi) south of the main island of Kyushu. Okinawa is connected to nearby islands near a land bridge: Katsuren Peninsula is connected via the Mid-Sea Road to Henza Island, Miyagi Island, Ikei Island, and Hamahiga Island. Similarly, from the Motobu Peninsula on the northwestern side, all of Sesoko-jima plus Yagaji Island and Kōri-jima are connected by bridges. Okinawa Island has several beaches such as Manza Beach, Emerald Beach, Okuma Beach, Zanpa Beach, Moon Beach and Sunset Beach (Chatan-cho).

Mount Yonaha is the highest mountain with 503 m (1,650 ft) in Kunigami, Okinawa. It is the second highest mountain in Okinawa Prefecture after Mount Omoto 525.5 m (1,724 ft) in Ishigaki, Okinawa.[26]

In the north are mainly igneous rocks. and Mount Yae and Nagodake. The northern region has a slightly large river and very little flat land. Acidity of the soil is distributed and there's e.g. pineapple cultivation.[27] The northern region has the Yanbaru subtropical rainforest. The Motobu Peninsula has limestone layers and karst development.[28]

In the center and south is mainly a Ryukyu limestone layer and mudstone.[28] The topography is flat, there are few hills over 100 m (328 ft) with very few rivers. In the southern region is karst topography with limestone that is easily eroded. The subtropical accelerated erosion so there are many drainages and uvala. There are many caves. The Gyokusendō cave has beautiful stalagmites and stalactites in the theme park Okinawa World, Nanjo. It is about five kilometers long. Only 890 meters are open to tourists.

The southern end of the island consists of uplifted coral reef, whereas the northern half has proportionally more igneous rock. The easily eroded limestone of the south has many caves, the most famous of which is Gyokusendō in Nanjō. An 850 m-long stretch is open to tourists.

The northernmost Cape Hedo is only 22 km (14 mi) away from Yoronjima. Cape Arasaki is the southernmost location of Okinawa island. It's sometimes confused with Cape Kiyanmisaki.

Flora and Fauna

The northern half of Okinawa has one of the largest tracts of subtropical rainforest in Asia called the Yanbaru. There are many endemic species of flora and fauna.[29][30] There are a small number of endemic Yanbaru kuina (also known as the Okinawa rail), a small flightless bird that is close to extinction. The critically endangered Okinawa woodpecker is also endemic on this island.

The Indian mongoose was introduced to the island to prevent the native habu pit viper from attacking the birds. It did not succeed in eliminating the habu, but instead preyed on birds, increasing the threat to the Okinawa rail.

The Okinawa rail

The Okinawa rail

Climate

The island has a humid subtropical climate bordering on a tropical rainforest climate. The island supports a dense northern forest and a rainy season occurring in the late spring.

Cliffs at Manzamo

Cliffs at Manzamo Village of Onna

Village of Onna A pond in Okinawa

A pond in Okinawa Cape Busena, in Nago, Okinawa

Cape Busena, in Nago, Okinawa- Sunset Beach (Chatan-cho)

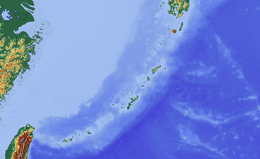

Map of Okinawa Prefecture with location of Okinawa Island

Map of Okinawa Prefecture with location of Okinawa Island

Cuisine

There are many local pubs (izakaya) and cafes that serve Okinawan cuisine and dishes, such as gōyā chanpurū (bitter melon stir fry), fu chanpurū (wheat gluten chanpurū), and tonkatsu (tenderized, breaded, fried pork cutlet). Okinawan soba is the signature dish and consists of wheat noodles served hot in a soup, usually with pork (rib or pork belly). This contrasts with the mainland soba, which is buckwheat noodles. Rafute, which is braised pork belly, is another popular Okinawan dish. American presence on the island has also led to some creative dishes such as taco rice, which is now a common meal served in bentos, and common use of spam.

Economy

Among the prefectures of Japan, Okinawa has the youngest and fastest-growing population, but has the lowest employment rate and average income. The island economy is primarily driven by tourism and the US military presence, with efforts in recent years to diversify into other sectors.[31]

The Motobu Peninsula has a large-scale quarry and cement factory due to the presence of limestone and karst.[32] There is also agriculture with tropical fruit such as Malpighia emarginata.[33]

Tourism

Tourist attractions include Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium (at one time the world's largest aquarium), Century Beach, Pineapple Park, the Orion Beer Factory and Hiji Falls. In recent years, Okinawa has become an increasingly popular destination for tourists from China and Southeast Asia.[34]

In the 2018 calendar year, Okinawa attracted 9,842,400 tourists, a positive growth of 4.7% from 9,396,200 in the previous 2017 calendar year.[35][36]

Military bases

The US military bases account for 4 to 5% of the island economy, but the economic impact may be double-edged, as the presence of the bases may be hampering investment (and tourism potential). The bases have been of declining economic importance, especially after Okinawan sovereignty returned to Japan.[14][37] There are also a smaller contingent of Japanese military bases on the island.

Several former US military facilities on Okinawa have been re-developed as commercial areas, most notably the American Village in Chatan, Okinawa, which opened in 1998, and the Aeon Mall Okinawa Rycom in Kitanakagusuku, Okinawa, which opened in 2015.[34]

Transportation and logistics

Naha Airport is the main transportation hub for the Ryukyu Islands and has an increasingly large role in regional logistics. All Nippon Airways opened a cargo hub at the airport in 2009, providing overnight freight service between Japan and other Asian countries.[34]

US military in Okinawa

The United States maintains American military bases in Japan as part of the U.S.-Japan alliance since 1951. Most US military are in Okinawa Prefecture. In 2013 there were approximately 50,000 U.S. military personnel stationed in Japan with 40,000 dependents and 5,500 American civilians employed by the United States Department of Defense.[38] About 26,000 US military personnel are on Okinawa Island.

There are 32 United States military bases on Okinawa Island.[14] Approximately 62% of all United States bases in Japan are on Okinawa.[39][40] They cover 25% of Okinawa island. The major bases are Futenma, Kadena, Hansen, Torii, Schwab, Foster, and Kinser.[41] There are 28 US military facilities on Okinawa. They are mainly concentrated in the central area. 8 out of 10 central municipalities have US facilities.

At one point Okinawa hosted approximately 1,200 nuclear warheads.[42] There were several nuclear weapons incidents on Okinawa and in the sea near the islands.[43][44][45]

The 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement officially ended the U.S. military occupation on Okinawa.[46]

Moving the bases

The bases primarily exist to serve Japanese and American strategic interests, but are unpopular with most local residents,[47] despite recent efforts to move the bases out of core areas following incidents involving military personnel and resultant protests (including the 1995 Okinawa rape incident).[48][49]

In 2012, an agreement was struck between the United States and Japan to reduce the number of US military personnel on the island, moving 9,000 personnel to other locations and moving bases out of heavily populated Greater Naha, but 10,000 Marines will remain on the island, along with other US military units.[41][50] Attempts to completely close bases on the southern third of the island, where 90% of the population lives (all but about 120,000 people) have been impeded by both the American desire that alternative locations be found where bases subject to closure could move to (e.g. Henoko Peninsula, mid-island), as well as by local Okinawan opposition to any suggested locations on the island (who demand no US troops at all anywhere on the island).[47] Tokyo says the US bases are important for national security. Locals complain that despite being home to less than 1% of Japan's population and area, Okinawa hosts the majority of the US military presence in Japan.[51] In late December 2013, the governor of Okinawa, Hirokazu Nakaima, gave permission for land reclamation to begin for a new US military base at Henoko reneging on previous promises, furthering the effort to consolidate the American troop presence on the island, though away from urban Naha.[52] This resulted in his loss of the governorship.

In December 2016 the USA returned 10,000 acres (40 km2) of the Northern Training Area on Okinawa to Japan. This reduced the footprint of the US forces by 20% on the island. It was the biggest land return since 1972.[53]

Architecture

Okinawa has various historical buildings and monuments. Such as feudal castles, ruins, UNESCO and other historical significant sites.

- Shuri Castle is the most famous castle on Okinawa and an UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Nakagusuku Castle is a gusuku in the village of Kitanakagusuku, Okinawa. This is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the 100 most famous castles in Japan.[54]

- The Cornerstone of Peace monument in Itoman commemorates the Battle of Okinawa and the end of World War II.[55] Nearby is the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum.

- Nakamura House (ja:中村家住宅 (沖縄県)) is an original 18th-century farmhouse in Kitanakagusuki.

- The former Japanese Navy Underground HQ (ja:海軍司令部壕)

- Katsuren Castle

- Nakijin Castle

Shuri Castle in Naha

Shuri Castle in Naha Shureimon

Shureimon Nakagusuku Castle ruins

Nakagusuku Castle ruins Cornerstone of Peace monument

Cornerstone of Peace monument Nakamura house

Nakamura house

Attractions

Natural

Other

- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium

- Mid-Sea Road

- Kokusaidori (ja:国際通り) main street of Naha

- The American Village in Chatan, Okinawa.

- Okinawa World

Festivals

There are multiple festivals on Okinawa throughout the year.[56]

- Shurijo Castle Park New Year's Celebration - January

- Cherry Blossom Festival - January, February

- Naha Hari Festival - May

- Orion Beerfest - August

- Eisa Dancers Parade - August

- Shuri Castle Festival - October

- Naha Great Tug-of-War Festival - October

- The Ryukyu Dynasty Festival Shuri - November

Transportation

Airport

Naha Airport is the main airport that serves the island.

Monorail

There is the Okinawa Urban Monorail (Yui Rail). The monorail runs from Naha Airport to Japan's south-easternmost monorail station, Akamine Station, before heading to its final destination of Tedako-Uranishi Station (Urasoe) and back.[57]

Buses

There are multiple bus companies, such as Toyo Bus, Ryukyu Bus Kotsu, Naha Bus, and Okinawa Bus.

Roads

The Okinawa Expressway is a toll road that runs from Naha to Nago, and has a speed limit of 80 km/h (50 mph), the highest on the island.

Ferries

There are many ferries to many of the nearby islands, such as Ie Shima. Tomarin Port in Naha, has ferries to nearby islands such as Aguni, Tokashiki and Zamami.

Regions and cities

Northern Okinawa

With Kunigami district, it has an area of 764 square kilometers (295 sq mi) and a population of about 120,000. There is much nature with subtropical rainforest.

- Nago

- Kunigami district

- Kunigami

- Ōgimi

- Higashi, Okinawa

- Motobu

- Nakijin

- Onna

- Ginoza

- Kinmu

Central Okinawa

With Nakagami district, it has an area of 280 square kilometers (110 sq mi) and a population of about 590,000. Most US military facilities are located here. Urasoe has strong connections with the southern municipalities, including the Southern Wide Area Municipal Area Administrative Association, Nishihara town, Nakagusuku village, and Kitanakagusuku Village. These belong to the Southern Wide Area Administrative Association. With Kunigami district or Yamabaru . It has an area of 764km 2 and a population of about 120,000. Rich nature remains.

- Okinawa City

- Urasoe

- Ginowan

- Uruma

- Nakagami district

- Yomitan

- Kadena

- Chatan

- Kitanakagusuku

- Nakagusuku

- Nishihara

Southern Okinawa

With Shimajiri district, it has an area of 198 square kilometers (76 sq mi) and a population of about 540,000. The capital is Naha.

- Naha

- Itoman

- Tomigusuku

- Nanjo

- Shimajiri district

- Haebaru

- Yonabaru

- Yaese

In popular media

Okinawa Island is featured in various movies, games, anime and manga.

- Teahouse of the August Moon (1956), starring Marlon Brando and Glenn Ford, was based on the hit Broadway play. The storyline of the play and the film were set on Okinawa, but actual filming took place in mainland Japan near Nara and in a studio in California.[58]

- Okinawa was the setting for the 1974 Japanese science fiction kaiju film Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, which featured a shisa dog as one of the monsters in the film; due to an awkward translation from Japanese to English, this monster is known in the film as King Caesar. Several scenes were filmed in the then-recently discovered Gyokusendo caves.

- Okinawa was also the setting for the 1986 film The Karate Kid, Part II, in which Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita) returns home to Okinawa with his student Daniel LaRusso (Ralph Macchio). Although Okinawa was the setting for the film, only short scenes of the film were actually filmed on Okinawa.

- A number of games in the Yakuza franchise are set partially on Okinawa: main protagonist Kazuma Kiryu sets up and runs an orphanage on the island.

- Okinawa was the setting of the World War II fighting in the 2016 movie Hacksaw Ridge, detailing the true story of US soldier Desmond Doss.

- Okinawa was the setting for the horror anime series Blood+ and sports manga Harukana Receive.

- Okinawa was also the setting for the 2018 Japanese superhero kaiju film Ultraman Geed the Movie.

- In Quentin Tarantino's 2003 film Kill Bill Vol. 1, protagonist Beatrix Kiddo travels to Okinawa in order to obtain a katana from master bladesmith Hattori Hanzo.

See also

- Geography of Japan

- Japanese archipelago

- History of the Ryukyu Islands

- Ryukyu Kingdom

- List of monarchs of Ryukyu Islands

- Shō Dynasties family tree

- Ryukyu Kingdom

- Okinawan martial arts

Photo gallery

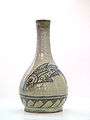

Okinawa Island is the home of Tsuboya-yaki, pottery in the Ryūkyūan tradition.

Okinawa Island is the home of Tsuboya-yaki, pottery in the Ryūkyūan tradition. Bullfighting (Tōgyū) arena. Okinawa is the home of a form of bullfighting sometimes compared to sumo

Bullfighting (Tōgyū) arena. Okinawa is the home of a form of bullfighting sometimes compared to sumo

References

-

"Statistical reports on the land area by prefectures and municipalities in Japan as of 2018" (PDF) (in Japanese). Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. 1 October 2018. p. 103. Retrieved 16 March 2019. - (in Japanese) 沖縄県推計人口データ一覧(Excel形式). Pref.okinawa.jp. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- 語彙詳細―首里・那覇方言. Okinawa Center of Language Study. Retrieved on 2014-12-02.

- "離島とは(島の基礎知識) (what is a remote island?)". MLIT (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism) (in Japanese). Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. 22 August 2015. Archived from the original (website) on 2007-07-13. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

MILT classification 6,852 islands(main islands: 5 islands, remote islands: 6,847 islands)

- "Okinawa Island | island, Japan". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Arashiro Toshiaki High School History of Ryukyu, Okinawa, Toyo Kikaku, 2001, p12,ISBN 4-938984-17-2 p20

- Ito, Masami, "Between a rock and a hard place", Japan Times, May 12, 2009, p. 3.

- The Demise of the Ryukyu Kingdom: Western Accounts and Controversy. Ed by Eitetsu Yamagushi and Yoko Arakawa. Ginowan-City, Okinawa: Yonushorin, 2002.

- "The Cornerstone of Peace – number of names inscribed". Okinawa Prefecture. Retrieved 4 February 2011

- "Battle of Okinawa: The Bloodiest Battle of the Pacific War". HistoryNet. 2006-06-12. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- Manchester, William (June 14, 1987). "The Bloodiest Battle Of All". The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- John Pike. "Battle of Okinawa". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- Mitchell, Jon (13 May 2012). "What awaits Okinawa 40 years after reversion?". The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- McCurry, Justin (15 May 2013). "China lays claim to Okinawa as territory dispute with Japan escalates". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Boehler, Patrick (15 May 2013). "Okinawa doesn't belong to Japan, says hawkish PLA general". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Shuri Castle, a symbol of Okinawa, destroyed in fire". The Japan Times Online. 2019-10-31. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 2019-10-31. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- "History of Shuri Castle" (PDF). oki-park.jp. Oki Park Official Site. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Central Okinawan language at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- Noguchi 2001, p. 76.

- "平成17年 全国都道府県市区町村別面積調" (PDF). 国土地理院. 2005-10-01. p. 189. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-20. Retrieved 2013-02-04.

- National Geographic magazine, June 1993

- Santrock, John W. A (2002). Topical Approach to Life-Span Development (4 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- 『日本統計年鑑 平成26年』「1-2 主な島」(2013年)p.13, 17

- 『日本歴史地名大系』「沖縄島」(2002年)p.73中段

- "Yonaha-dake". Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (日本大百科全書(ニッポニカ) “Large Encyclopedia of Japan (Nipponika)”) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-03-16.

- 『沖繩大百科事典 上巻』「沖縄島」(1983年)p.525

- 『日本歴史地名大系』「総論 自然環境」(2002年)p.24

- "Ufugi Nature Museum" (PDF). Yambaru Wildlife Conservation Centre. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- "United States Marine Corps Installations Natural Resource Program: Camp Smedley D. Butler, MCB" (PDF). United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Martin, Alexander (13 November 2014). "Okinawa's Reinvention Enters Next Phase". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "安和鉱山 琉球セメント". Archived from the original on 2013-12-17. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- "飲んで元気 アセローラ 本部町が産地をPR". 琉球新報. 2009-05-14. Archived from the original on 2013-06-23. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- Yoshida, Reiji (17 May 2015). "Economics of U.S. base redevelopment sway Okinawa mindset". The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "Okinawa fails to surpass Hawaii in terms of 2018 tourist numbers and increase rate". Ryukyu Shimpo - Okinawa, Japanese newspaper, local news. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- "Okinawa tourist numbers top those of Hawaii for first time". The Japan Times Online. 2018-02-09. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- Hongo, Jun (16 May 2012). "Economic reliance on bases won't last, trends suggest". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012.

- Yoshida, Reiji, "Basics of the U.S. military presence", Japan Times, 25 March 2008, p. 3.

- Archived 4 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Okinawa Prefectural Government

- http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ201606290073.html

- Jaffe, Greg; Heil, Emily; Harlan, Chico (26 April 2012), "U.S. comes to agreement with Japan to move 9,000 marines off Okinawa", The Washington Post, retrieved 28 April 2012

- Mitchell, Jon (June 4, 2013). "'Okinawa bacteria' toxic legacy crosses continents, spans generations". The Japan Times.

- Broder, John M. (May 9, 1989). "H-Bomb Lost at Sea in '65 Off Okinawa, U.S. Admits". The Los Angeles Times.

- Mitchell, Jon (November 11, 2013). "Okinawa: the junk heap of the Pacific; Decades of Pentagon pollution poison service members, residents and future plans for the island". The Japan Times.

- "Okinawa: the junk heap of the Pacific". The Japan Times. 11 November 2013.

- "Handover of Okinawa to Japan was prickly issue". The Japan Times. 14 May 2002.

- "Okinawa deal between US and Japan to move marines". BBC News. 27 April 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- "Okinawa rape case sparks resentment". The Japan Times. 13 February 2008.

- "Two US sailors accused of Okinawa rape". The Guardian. 17 October 2012.

- Ito, Masami (28 April 2012). "U.S., Japan tweak marine exit plan". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012.

- http://archive.marinecorpstimes.com/article/20140814/NEWS/308140041/U-S-military-takes-1st-step-Okinawa-relocation

- AP (27 December 2013). "Okinawa Governor Gives Go-ahead For New US Base". DailyDigest. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- Garamone, Jim (21 December 2016). "U.S. Returns 10,000 Acres of Okinawan Training Area to Japan". DOD News. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Nakagusuku Castle Remains". Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "The Cornerstone of Peace - statement of purpose". Okinawa Prefecture. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- "Events". Visit Okinawa Japan. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Yui Rail Museum: An Indoor Learning Experience For All". Okinawa.Org. Retrieved 2019-08-20.

- Erickson, Hal. Military Comedy Films: A Critical Survey and Filmography of Hollywood Releases Since 1918. McFarland, 2012, p. 174.

External links