Nile tilapia

The Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) is a species of tilapia, a cichlid fish native to the northern half of Africa and Israel.[2] Numerous introduced populations exist outside its natural range.[1][3] It is also commercially known as mango fish, nilotica, or boulti.[4] The first name leads to easy confusion with another tilapia traded commercially, the mango tilapia (Sarotherodon galilaeus).

| Nile tilapia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Wild type above, aquacultured type (likely of hybrid origin) below | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cichliformes |

| Family: | Cichlidae |

| Genus: | Oreochromis |

| Species: | O. niloticus |

| Binomial name | |

| Oreochromis niloticus | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

The Nile tilapia reaches up to 60 cm (24 in) in length,[2] and can exceed 5 kg (11 lb).[5] As typical of tilapia, males reach a larger size and grow faster than females.[5]

Wild, natural type Nile tilapias are brownish or grayish overall, often with indistinct banding on their body, and the tail is vertically striped. When breeding, males become reddish, especially on their fins.[5][6] Although commonly confused with the blue tilapia (O. aureus), that species lacks the striped tail-pattern, has a red edge to the dorsal fin (this edge is gray or black in Nile tilapia), and males are bluish overall when breeding. The two species can also be separated by meristics.[6] Because many tilapia in aquaculture and introduced around the world are selectively bred variants and/or hybrids, it often is not possible to identify them using the standard features that can be used in the wild, natural types.[6] The virtually unknown O. ismailiaensis has a plain tail but otherwise closely resembles —and may only be a variant of— the Nile tilapia.[7] Regardless, O. ismailiaensis might be extinct, as its only known habitat in northeastern Egypt has disappeared,[8] although similar-looking individuals (perhaps the same) are known from the vicinity.[7]

Nile tilapia can live for more than 10 years.[5]

Range and habitat

The Nile tilapia is native to larger parts of Africa, except Maghreb and almost all of Southern Africa. It is native to tropical West Africa, the Lake Chad basin and much of the Nile system, including lakes Tana, Albert and Edward–George, as well as lakes Kivu, Tanganyika and Turkana, and the Awash and Omo Rivers. In Israel, it is native to coastal river basins.[1][2] It has been widely introduced elsewhere, both in Africa and other continents, including tens of countries in Asia, Europe, North America and South America. In these places it often becomes highly invasive, threatening the native ecosystems and species.[1][2] However, some introduced populations historically labelled as Nile tilapia either are hybrids or another species; especially the Nile tilapia and blue tilapia often have been confused.[6]

The Nile tilapia can be found in most types of freshwater habitats, such as rivers, streams, canals, lakes and ponds, and ranging from sea level to an altitude of 1,830 m (6,000 ft).[1][2] It also occurs in brackish water, but is unable to survive long-term in full salt water.[2] The species has been recorded at water temperatures between 8 and 42 °C (46–108 °F), although typically above 13.5 °C (56.5 °F),[2] and the upper lethal limit usually is at 39–40 °C (102–104 °F).[1] There are also some variations depending on the population. For example, those in the northern part of its range survive down to the coldest temperatures, while isolated populations in hot springs in the Awash basin and at Suguta River generally live in waters that are at least 32–33 °C (90–91 °F).[8] Although Nile tilapia can survive down to relatively cold temperatures, breeding generally only occurs when the water reaches 24 °C (75 °F).[5]

Subspecies

Although FishBase considers the species as monotypic,[2] there are several distinctive populations that often are recognized as valid subspecies:[1][8][9]

- O. n. niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) – most of species' range

- O. n. baringoensis Trewavas, 1983 – Lake Baringo in Kenya

- O. n. cancellatus (Nichols, 1923) – Awash basin in Ethiopia

- O. n. eduardianus (Boulenger, 1912) – Albertine Rift Valley lakes

- O. n. filoa Trewavas, 1983 – hot springs in Awash basin in Ethiopia

- O. n. sugutae Trewavas, 1983 – Karpeddo soda springs at Suguta River in Kenya

- O. n. tana Seyoum & Kornfield, 1992 – Lake Tana in Ethiopia

- O. n. vulcani Trewavas, 1933 – Lake Turkana in Ethiopia and Kenya

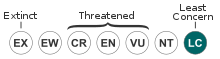

While the species is overall very widespread and common, the IUCN considers baringoensis as endangered, sugutae as vulnerable and filoa as data deficient.[1]

A population found in Lake Bogoria appears to be an undescribed subspecies.[8]

The forms referred to as Oreochromis (or Tilapia) nyabikere and kabagole seem to belong to this species, too. An undescribed population found at, for example, Wami River, Lake Manyara, and Tingaylanda seems to be a close relative.[10]

Behavior

Feeding

The Nile tilapia is mostly a herbivore, but with omnivorous tendencies, especially when young.[2] They mostly feed on phytoplankton and algae, and in some populations other macrophytes also are important.[1] Other recorded food items are detritus and aquatic insect larvae,[2] including those of mosquitoes, making it a possible tool in the fight against malaria in Africa.[11] However, when introduced outside its native range it often becomes invasive, threatening more localized species.[2]

The Nile tilapia typically feeds during daytime hours. This suggests that, similar to trout and salmon, it exhibits a behavioral response to light as a main factor contributing to feeding activity. Due to their fast reproductive rate, however, overpopulation often results within groups of Nile tilapia. To obtain the necessary nutrients, night feeding may also occur due to competition for food during the daylight hours. A recent study found evidence that, contrary to popular belief, size dimorphism between the sexes results from differential food conversion efficiency rather than differential amounts of food consumed. Hence, although males and females eat equal amounts of food, males tend to grow larger due to a higher efficiency of converting food to energy.[12]

Social organization

Groups of Nile tilapia establish social hierarchies in which the dominant males have priority for both food and mating. Circular nests are built predominantly by males through mouth digging to become future spawning sites. These nests often become sites of intense courtship rituals and parental care.[13] Like other fish, the Nile tilapia travels almost exclusively in schools. Although males settle down in their crafted nesting zones, females travel between zones to find mates, resulting in competition between the males for females.

Like other tilapias, such as Mozambique tilapia, dominance between the males is established first through non-contact displays such as lateral display and tail beats. Unsuccessful attempts to reconcile the hierarchy results in contact fighting to inflict injuries. Nile tilapia has been observed to modify their fighting behavior based upon experiences during development. Thus, experience in a certain form of agonistic behavior results in differential aggressiveness among individuals.[14] Once the social hierarchy is established within a group, the dominant males enjoy the benefits of both increased access to food and an increased number of mates. However, social interactions between males in the presence of females results in higher energy expenditures as a consequence of courtship displays and sexual competition.[12]

Reproduction

Typical of most fish, the Nile tilapia reproduces through mass spawning of a brood within a nest made by the male. In such an arrangement, territoriality and sexual competition amongst the males lead to large variations in reproductive success for individuals among a group. The genetic consequence of such behavior is reduced genetic variability in the long run, as inbreeding is likely to occur among different generations due to differential male reproductive success.[15] Perhaps driven by reproductive competition, tilapias reproduce within a few months after birth. The relatively young age of sexual maturation within Nile tilapia leads to high birth and turnover rates. Consequently, the rapid reproductive rate of individuals can actually have a negative impact on growth rate, leading to the appearance of stunted tilapia as a result of a reduction in somatic growth in favor of sexual maturation.[16]

Female Nile tilapia, in the presence of other females either visually or chemically, exhibit shortened interspawning intervals. Although parental investment by a female extends the interspawning period, female tilapia that abandon their young to the care of a male gain this advantage of increased interspawning periods. One of the possible purposes behind this mechanism is to increase the reproductive advantage of females that do not have to care for young, allowing them more opportunities to spawn.[17] For males, reproductive advantage goes to the more dominant males. Studies have found that males have differential levels of gonadotropic hormones responsible for spermatogenesis, with dominant males having higher levels of the hormone. Thus, selection has favored larger sperm production with more successful males. Similarly, dominant males have both the best territory in terms of resources and the greatest access to mates.[18] Furthermore, visual communication between Nile tilapia mates both stimulates and modulates reproductive behavior between partners such as courtship, spawning frequency, and nest building.[13]

Parental care

Species belonging to the genus Oreochromis typically care for their young through mouthbrooding, oral incubation of the eggs and larvae. Similar to other tilapia, Nile tilapia are maternal mouthbrooders and extensive care is therefore provided almost exclusively by the female. After spawning in a nest made by a male, the young fry or eggs are carried in the mouth of the mother for a period of 12 days. Sometimes, the mother will push the young back into her mouth if she believes they are not ready for the outside. Nile tilapias also demonstrate parental care in times of danger. When approached by a danger, the young often swim back into the protection of their mother's mouth.[19] However, mouthbrooding leads to significant metabolic modifications for the parents, usually the mother, as reflected by fluctuations in body weight and low fitness. Thus, parental-offspring conflict can be observed through the costs and benefits of mouthbrooding. On one hand, protection of the young ensures passage of an individual's genes into the future generations; however, caring for the young also reduces an individual's own reproductive fitness.[16]

As stated in the reproduction section, female Nile tilapia exhibiting parental care show extended interspawning periods. One of the benefits of this extension results in slowing down vitellogenesis (yolk deposition) to increase the survival rate of one's own young. The size of spawned eggs correlates directly with advantages concerning hatching time, growth, survival, and onset of feeding since increased egg size means increased nutrients for the developing young. Thus, one of the reasons behind a delayed interspawning period by female Nile tilapia may be for the benefit of offspring survival.[17][20]

Aquaculture

Tilapia, likely the Nile tilapia, was well known as food fish in Ancient Egypt and commonly featured in their art (paintings and sculptures). This includes a 4000-year-old tomb illustration that shows them in man-made ponds, likely an early form of aquaculture.[5][21] In modern aquaculture, wild-type Nile tilapia are not farmed very often because of the dark color of their flesh, that is undesirable for many customers, and because of the reputation the fish has as being a trash fish.[22] However, they are fast-growing and produce good fillets; leucistic ("red") breeds which have lighter meat have been developed to counter the consumer distaste for darker meat.

Hybrid stock is also used in aquaculture; Nile × blue tilapia hybrids are usually rather dark, but a light-colored hybrid breed known as "Rocky Mountain White" tilapia is often grown due to its very light flesh and tolerance of low temperatures.[22]

As food

The red-hybrid Nile tilapia is known in the Thai language as pla thapthim (Thai: ปลาทับทิม), meaning "pomegranate fish" or "ruby fish".[23] This type of tilapia is very popular in Thai cuisine where it is prepared in a variety of ways.[24]

The black and white striped tilapia pla nin (Thai: ปลานิล), meaning "Nile fish", has darker flesh and is commonly either salted and grilled or deep-fried, and it can also be steamed with lime (pla nin nueng manao).[25]

Nile tilapia, called بلطي bulṭī in Arabic, is (being native to Egypt) among the most common fish in Egyptian cuisine, and probably the most common in regions far from the coast. It is generally either battered and pan-fried whole (بلطي مقلي bulṭī maqlī [bʊltˤiː maʔliː]) or grilled whole (بلطي مشوي bulṭī mashwī [bʊltˤiː maʃwiː]). Like other fish in Egypt, is generally served with rice cooked with onions and other seasonings to turn it red.

Tilapia, often farmed, is a popular and common supermarket fish in the United States. In India Nile Tilapia is the most dominant fish in some of the south Indian reservoirs and available throughout the year. O. niloticus grows faster and reaches bigger sizes in short span of time. The littoral areas of Kelavarappalli reservoir are full of nests of Nile Tilapia and they breed during south-west monsoon (July–September). The fish mainly feeds on detritus. The zooplankton, phytoplankton and macrophytes also were recorded occasionally from the gut of Nile Tilapia. There is a heavy demand especially from local poor people as this fish is affordable to the lowest income group in this area.[26]

See also

- Nile perch — a similar-named but different fish that grows much larger and is highly predatory

References

- Snoeks, J.; Freyhof, J.; Geelhand, D. & Hughes, A. (2018). "Oreochromis niloticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T166975A49922878. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T166975A49922878.en.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2015). "Oreochromis niloticus" in FishBase. November 2015 version.

- Azevedo-Santos, V.M.; O. Rigolin-Sá; and F.M. Pelicice (2011). "Growing, losing or introducing? Cage aquaculture as a vector for the introduction of non-native fish in Furnas Reservoir, Minas Gerais, Brazil". Neotropical Ichthyology. 9 (4): 915–919. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252011000400024.

- Ibrahim, A. A.; El-Zanfaly, H. T. (1980). "Boulti (Tilapia nilotica Linn.) fish paste 1. Preparation and chemical composition". Zeitschrift für Ernährungswissenschaft. 19 (3): 159–162. doi:10.1007/BF02018780.

- Nico, L.G.; P.J. Schofield; M.E. Neilson (2019). "Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758)". Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Nico, L.G.; P.J. Schofield; M.E. Neilson (2019). "Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758)". U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Neumann, D.; H. Obermaier; T. Moritz (2016). "Annotated checklist for fishes of the Main Nile Basin in the Sudan and Egypt based on recent specimen records (2006-2015)". Cybium. 40 (4): 287–317. doi:10.26028/cybium/2016-404-004.

- Ford, A.G.P.; et al. (2019). "Molecular phylogeny of Oreochromis (Cichlidae: Oreochromini) reveals mito-nuclear discordance and multiple colonisation of adverse aquatic environments". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 136: 215–226. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2019.04.008.

- Trewavas, E. (1983). Tilapiine Fishes of the genera Sarotherodon, Oreochromis and Danakilia. Natural History Museum, London.

- Nagl, Sandra; Tichy, Herbert; Mayer, Werner E.; Samonte, Irene E.; McAndrew, Brendan J.; Klein, Jan (2001). "Classification and Phylogenetic Relationships of African Tilapiine Fishes Inferred from Mitochondrial DNA Sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 20 (3): 361–374. doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.0979. PMID 11527464.

- "Nile tilapia can fight malaria mosquitoes", BBC News, 8 August 2007.

- TOGUYENI, A; FAUCONNEAU, B; BOUJARD, T; FOSTIER, A; KUHN, E; MOL, K; BAROILLER, J (1 August 1997). "Feeding behaviour and food utilisation in tilapia, Oreochromis Niloticus: Effect of sex ratio and relationship with the endocrine status". Physiology & Behavior. 62 (2): 273–279. doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(97)00114-5. PMID 9251968.

- Castro, A.L.S.; Gonçalves-de-Freitas, E.; Volpato, G.L.; Oliveira, C. (1 April 2009). "Visual communication stimulates reproduction in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.)". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 42 (4): 368–374. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2009000400009. PMID 19330265.

- Barki, Assaf; Gilson L. Volpato (October 1998). "Early social environment and the fighting behaviour of young Oreochromis niloticus (Pisces, Cichlidae)". Behaviour. 135 (7): 913–929. doi:10.1163/156853998792640332.

- Fessehaye, Yonas; El-bialy, Zizy; Rezk, Mahmoud A.; Crooijmans, Richard; Bovenhuis, Henk; Komen, Hans (15 June 2006). "Mating systems and male reproductive success in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in breeding hapas: A microsatellite analysis". Aquaculture. 256 (1–4): 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.02.024.

- Peña-Mendoza, B.; J. L. Gómez-Márquez; I. H. Salgado-Ugarte; D. Ramírez-Noguera (September 2005). "Reproductive biology of Oreochromis niloticus (Perciformes: Cichlidae) at Emiliano Zapata dam, Morelos, Mexico". Revista de Biología Tropical. 53 (3/4): 515–522. doi:10.15517/rbt.v53i3-4.14666.

- Tacon, P. (1 November 1996). "Relationships between the expression of maternal behaviour and ovarian development in the mouthbrooding cichlid fish Oreochromis Niloticus". Aquaculture. 146 (3–4): 261–275. doi:10.1016/S0044-8486(96)01389-0.

- Pfennig, F.; Kurth, T.; Meissner, S.; Standke, A.; Hoppe, M.; Zieschang, F.; Reitmayer, C.; Gobel, A.; Kretzschmar, G.; Gutzeit, H. O. (26 October 2011). "The social status of the male Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) influences testis structure and gene expression". Reproduction. 143 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1530/REP-11-0292. PMID 22031714.

- "Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia)" (PDF). UWI.

- Rana, Kausik J. (1986). "Parental influences on egg quality, fry production and fry performance in Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus) and O. mossambicus (Peters)". University of Stirling.

- Soliman, N.F.; D.M.M. Yacout (2016). "Aquaculture in Egypt: status, constraints and potentials". Aquaculture International. 24 (5): 1201–1227. doi:10.1007/s10499-016-9989-9.

- Management Guidelines of Red Tilapia Culture in Cages, Trang Province (in Thai)

- "Recipes for Thaptim Fish". Archived from the original on 2009-09-10. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- Fish breeding in Thailand

- Feroz Khan, M.; Panikkar, Preetha (2009). "Assessment of impacts of invasive fishes on the food web structure and ecosystem properties of a tropical reservoir in India". Ecological Modelling. 220 (18): 2281–2290. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.05.020.

External links

- View the oreNil2 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.

Further reading

- "Oreochromis niloticus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- Bardach, J.E.; Ryther, J.H. & McLarney, W.O. (1972): Aquaculture. the Farming and Husbandry of Freshwater and Marine Organisms. John Wiley & Sons.