Nightjar

Nightjars are medium-sized nocturnal or crepuscular birds in the subfamily Caprimulginae and in the family Caprimulgidae, characterised by long wings, short legs and very short bills. They are sometimes called goatsuckers, due to the ancient folk tale that they sucked the milk from goats (the Latin for goatsucker is Caprimulgus), or bugeaters,[1] due to their insectivore diet. Some New World species are called nighthawks. The English word 'nightjar' originally referred to the European nightjar.

| Nightjar | |

|---|---|

_(2).jpg) | |

| Great eared nightjar | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Caprimulgiformes |

| Family: | Caprimulgidae Vigors, 1825 |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

| |

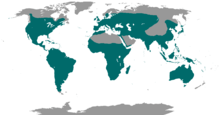

| Global range of nightjars and allies | |

Nightjars are found around the world except in New Zealand and some islands of Oceania. They are mostly active in the late evening and in early morning or at night, usually nest on the ground, and feed predominantly on moths and other large flying insects.

Most have small feet, of little use for walking, and long pointed wings. Their soft plumage is cryptically coloured to resemble bark or leaves. Some species, unusual for birds, perch along a branch, rather than across it. This helps to conceal them during the day.

The common poorwill, Phalaenoptilus nuttallii, is unique as a bird that undergoes a form of hibernation, becoming torpid and with a much reduced body temperature for weeks or months, although other nightjars can enter a state of torpor for shorter periods.[2]

Nightjars lay one or two patterned eggs directly onto bare ground. It has been suggested that nightjars will move their eggs and chicks from the nesting site in the event of danger by carrying them in their mouths. This suggestion has been repeated many times in ornithology books, but surveys of nightjar research have found very little evidence to support this idea.[3][4]

Systematics

Traditionally, nightjars have been divided into three subfamilies: the Caprimulginae, or typical nightjars with 79 known species, and the Chordeilinae, or nighthawks of the New World with 10 known species. The two groups are similar in most respects, but the typical nightjars have rictal bristles, longer bills, and softer plumage. In their pioneering DNA-DNA hybridisation work, Sibley and Ahlquist found that the genetic difference between the eared nightjars and the typical nightjars was, in fact, greater than that between the typical nightjars and the nighthawks of the New World. Accordingly, they placed the eared nightjars in a separate family: Eurostopodidae (9 known species), but the family has not yet been widely adopted.

Subsequent work, both morphological and genetic, has provided support for the separation of the typical and the eared nightjars, and some authorities have adopted this Sibley-Ahlquist recommendation, and also the more far-reaching one to group all the owls (traditionally Strigiformes) together in the Caprimulgiformes. The listing below retains a more orthodox arrangement, but recognise the eared nightjars as a separate group. For more detail and an alternative classification scheme, see Caprimulgiformes and Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy.

| Phylogeny of Caprimulgidae[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

- †Ventivorus Mourer-Chauviré 1988

- Subfamily Eurostopodinae[6]

- Genus Eurostopodus (7 species)

- Genus Lyncornis (2 species)

- Subfamily Caprimulginae (typical nightjars)

- Genus Gactornis – collared nightjar

- Genus Nyctipolus – (2 species)

- Genus Nyctidromus – (2 species)

- Genus Hydropsalis – (4 species)

- Genus Siphonorhis – (2 species)

- Genus Nyctiphrynus – (4 species)

- Genus Phalaenoptilus – common poorwill

- Genus Antrostomus – (12 species)

- Genus Caprimulgus – (40 species, including the European nightjar)

- Genus Setopagis – (4 species)

- Genus Uropsalis – (2 species)

- Genus Macropsalis – long-trained nightjar

- Genus Eleothreptus – (2 species)

- Genus Systellura – (2 species)

- Subfamily Chordeilinae (nighthawks)

- Genus Chordeiles (6 species)

- Genus Nyctiprogne (2 species)

- Genus Lurocalis (2 species)

Also see a list of nightjars, sortable by common and binomial names.

Distribution and habitat

.jpg)

The nightjars have a global distribution, being found on all the continents other than Antarctica. They are also absent from some extremely arid deserts, such as the Sahara Desert and the deserts of central Asia, and polar regions of the far north. They are also found in some island groups such as Madagascar, the Seychelles, New Caledonia and the islands of Caribbean.[7] The nighthawks have a New World distribution, and the eared nightjars are Asian and Australian, whereas the typical nightjars are global in distribution.[7]

Nightjars can occupy all elevations from sea-level to 4,200 m (13,800 ft), and a number of species are montane specialists. They occupy a wide range of habitats, from deserts to rainforest, but are most common in open country with some vegetation.[7]

A number of species undertake migrations, although the secretive nature of the family means these are poorly understood. Species that live in the far north, such as the European nightjar or the common nighthawk, will move south with the onset of winter. Geolocators placed on European nightjars in southern England found they wintered in the south of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[8] Other species make shorter migrations.[7]

Conservation and status

Some species of nightjar are threatened with extinction. It has been suggested that road-kills of this species by cars is a major cause of mortality for many members of the family. This is because of their habit of resting and roosting on roads.[9]

Working out conservation strategies for some species of nightjar presents a particular challenge common to other hard-to-see families of birds; in a few cases, scientists do not have enough data on whether a bird is rare or not. This has nothing to do with any lack of effort. It reflects, rather, the difficulty in locating and identifying a small number of those species of birds among the 10,000 or so that exist in the world, given the limitations of human beings. A perfect example is the Vaurie's nightjar in China's south-western Xinjiang. It has been seen for certain only once, in 1929, a specimen that was held in the hand. Surveys in the 1970s and 1990s failed to find it.[10] It is perfectly possible that it has evolved as a species that can really be identified in the wild only by other Vaurie's nightjars, rather than by humans. As a result, scientists do not know whether it is extinct, endangered, or even locally common.

In history and popular culture

- Nighthawk as a name has been applied to numerous places, characters, and objects throughout history

- Nebraska's state nickname was once the "Bugeater State" and its people were known as "bugeaters" (likely named after the Common nighthawk).[11][12][1] The Nebraska Cornhuskers college athletic teams were also briefly known the Bugeaters, before adopting their current name, which was also adopted by the state as a whole. A semi-professional soccer team in Nebraska now uses the Bugeaters moniker.

Gallery

Lesser nighthawk

Lesser nighthawk Standard-winged nightjar

Standard-winged nightjar Pauraque

Pauraque Nightjar

Nightjar

References

- U. S. An Index to the United States of America: Historical, Geographical and Political. A Handbook of Reference Combining the "curious" in U. S. History. Boston, MA: D. Lothrop Company. 1890. p. 77.

- Lane JE, Brigham RM, Swanson DL (2004). "Daily torpor in free-ranging whip-poor-wills (Caprimulgus vociferus)". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 77 (2): 297–304. doi:10.1086/380210. PMID 15095249.

- Jackson, H.D. (2007). "A review of the evidence for the translocation of eggs and young by nightjars (Caprimulgidae)". Ostrich: Journal of African Ornithology. 78 (3): 561–572. doi:10.2989/OSTRICH.2007.78.3.2.313.

- Jackson, H.D. (1985). "Commentary and Observations on the Alleged Transportation of Eggs and Young by Caprimulgids" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 97 (3): 381–385.

- Boyd, John (2007). "Caprimulgidae: Nightjars, Nighthawks" (PDF). John Boyd's website. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "Comparison of IOC 8.1 with other world lists". IOC World Bird List. v8.1. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Cleere, N. (2017). del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi; Christie, David A.; de Juana, Eduardo (eds.). "Nightjars (Caprimulgidae)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- Cresswell, Brian; Edwards, Darren (February 2013). "Geolocators reveal wintering areas of European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus)" (PDF). Bird Study. 60 (1): 77–86. doi:10.1080/00063657.2012.748714.

- Jackson, H.D.; Slotow, R. (10 July 2015). "A review of Afrotropical nightjar mortality, mainly road kills". Ostrich. 73 (3–4): 147–161. doi:10.1080/00306525.2002.11446745.

- Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 5, Birdlife International/Lynx Edicions, 1999

- "The State of Nebraska - An Introduction to the Cornhuskers State from NETSTATE.COM". www.netstate.com. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Nancy Capace, Encyclopedia of Nebraska. Somerset Publishers, Inc., Jan 1, 1999, p2-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caprimulgidae. |

- Nightjar videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Nightjar sounds on xeno-canto.org