Neuschwanstein Castle

Neuschwanstein Castle (German: Schloss Neuschwanstein, pronounced [nɔʏˈʃvaːnʃtaɪn], Southern Bavarian: Schloss Neischwanstoa) is a 19th-century Romanesque Revival palace on a rugged hill above the village of Hohenschwangau near Füssen in southwest Bavaria, Germany. The palace was commissioned by Ludwig II of Bavaria as a retreat and in honour of Richard Wagner. Ludwig paid for the palace out of his personal fortune and by means of extensive borrowing, rather than Bavarian public funds.

| Neuschwanstein Castle | |

|---|---|

Neuschwanstein Castle in July 2013 | |

Location within Germany | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Romanesque Revival |

| Location |  Hohenschwangau, Germany

Hohenschwangau, Germany |

| Coordinates | 47°33′27″N 10°44′58″E |

| Construction started | 5 September 1869 |

| Completed | c. 1886 (opened) |

| Owner | Bavarian Palace Department |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Eduard Riedel |

| Civil engineer | Eduard Riedel, Georg von Dollmann, Julius Hofmann |

| Other designers | Ludwig II, Christian Jank |

The castle was intended as a home for the king, until he died in 1886. It was open to the public shortly after his death.[1] Since then more than 61 million people have visited Neuschwanstein Castle. More than 1.3 million people visit annually, with as many as 6,000 per day in the summer.[3]

Location

The municipality of Schwangau lies at an elevation of 800 m (2,620 ft) at the southwest border of the German state of Bavaria. Its surroundings are characterised by the transition between the Alpine foothills in the south (toward the nearby Austrian border) and a hilly landscape in the north that appears flat by comparison.

In the Middle Ages, three castles overlooked the villages. One was called Schwanstein Castle.[nb 1] In 1832, Ludwig's father King Maximilian II of Bavaria bought its ruins to replace them with the comfortable neo-Gothic palace known as Hohenschwangau Castle. Finished in 1837, the palace became his family's summer residence, and his elder son Ludwig (born 1845) spent a large part of his childhood here.[4]

Vorderhohenschwangau Castle and Hinterhohenschwangau Castle[nb 2] sat on a rugged hill overlooking Schwanstein Castle, two nearby lakes (Alpsee and Schwansee), and the village. Separated by only a moat, they jointly consisted of a hall, a keep, and a fortified tower house.[5] In the nineteenth century only ruins remained of the twin medieval castles, but those of Hinterhohenschwangau served as a lookout place known as Sylphenturm.[6]

The ruins above the family palace were known to the crown prince from his excursions. He first sketched one of them in his diary in 1859.[7] When the young king came to power in 1864, the construction of a new palace in place of the two ruined castles became the first in his series of palace building projects.[8] Ludwig called the new palace New Hohenschwangau Castle; only after his death was it renamed Neuschwanstein.[9] The confusing result is that Hohenschwangau and Schwanstein have effectively swapped names: Hohenschwangau Castle replaced the ruins of Schwanstein Castle, and Neuschwanstein Castle replaced the ruins of the two Hohenschwangau Castles.

History

Inspiration and design

Neuschwanstein embodies both the contemporaneous architectural fashion known as castle romanticism (German: Burgenromantik), and Ludwig II's immoderate enthusiasm for the operas of Richard Wagner.

In the 19th century, many castles were constructed or reconstructed, often with significant changes to make them more picturesque. Palace-building projects similar to Neuschwanstein had been undertaken earlier in several of the German states and included Hohenschwangau Castle, Lichtenstein Castle, Hohenzollern Castle, and numerous buildings on the River Rhine such as Stolzenfels Castle.[10] The inspiration for the construction of Neuschwanstein came from two journeys in 1867—one in May to the reconstructed Wartburg near Eisenach,[11] another in July to the Château de Pierrefonds, which Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was transforming from a ruined castle into a historistic palace.[12][nb 3]

The king saw both buildings as representatives of a romantic interpretation of the Middle Ages, as well as the musical mythology of his friend Wagner, whose operas Tannhäuser and Lohengrin had made a lasting impression on him.[13]

In February 1868, Ludwig's grandfather Ludwig I died, freeing the considerable sums that were previously spent on the abdicated king's appanage.[8][nb 4] This allowed Ludwig II to start the architectural project of building a private refuge in the familiar landscape far from the capital Munich, so that he could live out his idea of the Middle Ages.

It is my intention to rebuild the old castle ruin of Hohenschwangau near the Pöllat Gorge in the authentic style of the old German knights' castles, and I must confess to you that I am looking forward very much to living there one day [...]; you know the revered guest I would like to accommodate there; the location is one of the most beautiful to be found, holy and unapproachable, a worthy temple for the divine friend who has brought salvation and true blessing to the world. It will also remind you of "Tannhäuser" (Singers' Hall with a view of the castle in the background), "Lohengrin'" (castle courtyard, open corridor, path to the chapel) ...

— Ludwig II, Letter to Richard Wagner, May 1868[14]

The building design was drafted by the stage designer Christian Jank and realised by the architect Eduard Riedel.[15] For technical reasons, the ruined castles could not be integrated into the plan. Initial ideas for the palace drew stylistically on Nuremberg Castle and envisaged a simple building in place of the old Vorderhohenschwangau Castle, but they were rejected and replaced by increasingly extensive drafts, culminating in a bigger palace modelled on the Wartburg.[16] The king insisted on a detailed plan and on personal approval of each and every draft.[17] Ludwig's control went so far that the palace has been regarded as his own creation, rather than that of the architects involved.[18]

Whereas contemporary architecture critics derided Neuschwanstein, one of the last big palace building projects of the nineteenth century, as kitsch, Neuschwanstein and Ludwig II's other buildings are now counted among the major works of European historicism.[19][20] For financial reasons, a project similar to Neuschwanstein – Falkenstein Castle – never left the planning stages.[21]

The palace can be regarded as typical for nineteenth-century architecture. The shapes of Romanesque (simple geometric figures such as cuboids and semicircular arches), Gothic (upward-pointing lines, slim towers, delicate embellishments) and Byzantine architecture and art (the Throne Hall décor) were mingled in an eclectic fashion and supplemented with 19th-century technical achievements. The Patrona Bavariae and Saint George on the court face of the Palas (main building) are depicted in the local Lüftlmalerei style, a fresco technique typical for Allgäu farmers' houses, while the unimplemented drafts for the Knights' House gallery foreshadow elements of Art Nouveau.[22] Characteristic of Neuschwanstein's design are theatre themes: Christian Jank drew on coulisse drafts from his time as a scenic painter.[23]

The basic style was originally planned to be neo-Gothic but the palace was primarily built in Romanesque style in the end. The operatic themes moved gradually from Tannhäuser and Lohengrin to Parsifal.[24]

Construction

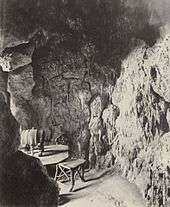

.jpg)

In 1868, the ruins of the medieval twin castles were completely demolished; the remains of the old keep were blown up.[25] The foundation stone for the palace was laid on 5 September 1869; in 1872 its cellar was completed and in 1876, everything up to the first floor, the gatehouse being finished first. At the end of 1882 it was completed and fully furnished, allowing Ludwig to take provisional lodgings there and observe the ongoing construction work.[24] In 1874, management of the civil works passed from Eduard Riedel to Georg von Dollmann.[26] The topping out ceremony for the Palas was in 1880, and in 1884, the king was able to move in to the new building. In the same year, the direction of the project passed to Julius Hofmann, after Dollmann had fallen from the King's favour.

The palace was erected as a conventional brick construction and later encased in various types of rock. The white limestone used for the fronts came from a nearby quarry.[27] The sandstone bricks for the portals and bay windows came from Schlaitdorf in Württemberg. Marble from Untersberg near Salzburg was used for the windows, the arch ribs, the columns and the capitals. The Throne Hall was a later addition to the plans and required a steel framework.

The transport of building materials was facilitated by scaffolding and a steam crane that lifted the material to the construction site. Another crane was used at the construction site. The recently founded Dampfkessel-Revisionsverein (Steam Boiler Inspection Association) regularly inspected both boilers.

For about two decades the construction site was the principal employer in the region.[28] In 1880, about 200 craftsmen were occupied at the site,[29] not counting suppliers and other persons indirectly involved in the construction. At times when the king insisted on particularly close deadlines and urgent changes, reportedly up to 300 workers per day were active, sometimes working at night by the light of oil lamps. Statistics from the years 1879/1880 support an immense amount of building materials: 465 tonnes (513 short tons) of Salzburg marble, 1,550 t (1,710 short tons) of sandstone, 400,000 bricks and 2,050 cubic metres (2,680 cu yd) of wood for the scaffolding.

In 1870, a society was founded for insuring the workers, for a low monthly fee, augmented by the king. The heirs of construction casualties (30 cases are mentioned in the statistics) received a small pension.

In 1884, the king was able to move into the (still unfinished) Palas,[30] and in 1885, he invited his mother Marie to Neuschwanstein on the occasion of her 60th birthday.[nb 5] By 1886, the external structure of the Palas (hall) was mostly finished.[30] In the same year, Ludwig had the first, wooden Marienbrücke over the Pöllat Gorge replaced by a steel construction.

Despite its size, Neuschwanstein did not have space for the royal court, but contained only the king's private lodging and servants' rooms. The court buildings served decorative, rather than residential purposes:[9] The palace was intended to serve Ludwig II as a kind of inhabitable theatrical setting.[30] As a temple of friendship it was also dedicated to the life and work of Richard Wagner, who died in 1883 before he had set foot in the building.[31] In the end, Ludwig II lived in the palace for a total of only 172 days.[32]

Funding

The king's wishes and demands expanded during the construction of Neuschwanstein, and so did the expenses. Drafts and estimated costs were revised repeatedly.[33] Initially a modest study was planned instead of the great throne hall, and projected guest rooms were struck from the drafts to make place for a Moorish Hall, which could not be realised due to lack of resources. Completion was originally projected for 1872, but deferred repeatedly.[33]

Neuschwanstein, the symbolic medieval knight's castle, was not Ludwig II's only huge construction project. It was followed by the rococo style Lustschloss of Linderhof Palace and the baroque palace of Herrenchiemsee, a monument to the era of absolutism.[8] Linderhof, the smallest of the projects, was finished in 1886, and the other two remain incomplete. All three projects together drained his resources. The king paid for his construction projects by private means and from his civil list income. Contrary to frequent claims, the Bavarian treasury was not directly burdened by his buildings.[30][34] From 1871, Ludwig had an additional secret income in return for a political favour given to Otto von Bismarck.[nb 6]

The construction costs of Neuschwanstein in the king's lifetime amounted to 6.2 million marks (equivalent to 40 million 2009 €),[35] almost twice the initial cost estimate of 3.2 million marks.[34] As his private means were insufficient for his increasingly escalating construction projects, the king continuously opened new lines of credit.[36] In 1876, a court counselor was replaced after pointing out the danger of insolvency.[37] By 1883 he already owed 7 million marks,[38] and in spring 1884 and August 1885 debt conversions of 7.5 million marks and 6.5 million marks, respectively, became necessary.[36]

Even after his debts had reached 14 million marks, Ludwig insisted on continuation of his architectural projects; he threatened suicide if his creditors seized his palaces.[37] In early 1886, Ludwig asked his cabinet for a credit of 6 million marks, which was denied. In April, he followed Bismarck's advice to apply for the money to his parliament. In June the Bavarian government decided to depose the king, who was living at Neuschwanstein at the time. On 9 June he was incapacitated, and on 10 June he had the deposition commission arrested in the gatehouse.[39] In expectation of the commission, he alerted the gendarmerie and fire brigades of surrounding places for his protection.[36] A second commission headed by Bernhard von Gudden arrived on the next day, and the king was forced to leave the palace that night. Ludwig was put under the supervision of von Gudden. On 13 June, both died under mysterious circumstances in the shallow shore water of Lake Starnberg near Berg Castle.

Simplified completion

At the time of Ludwig's death the palace was far from complete. He slept only 11 nights in the castle. The external structures of the Gatehouse and the Palas were mostly finished but the Rectangular Tower was still scaffolded. Work on the Bower had not started, but was completed in a simplified form by 1892 without the planned figures of the female saints. The Knights' House was also simplified. In Ludwig's plans the columns in the Knights' House gallery were held as tree trunks and the capitals as the corresponding crowns. Only the foundations existed for the core piece of the palace complex: a keep of 90 metres (300 ft) height planned in the upper courtyard, resting on a three-nave chapel. This was not realised,[17] and a connection wing between the Gatehouse and the Bower saw the same fate.[40] Plans for a castle garden with terraces and a fountain west of the Palas were also abandoned after the king's death.

The interior of the royal living space in the palace was mostly completed in 1886; the lobbies and corridors were painted in a simpler style by 1888.[41] The Moorish Hall desired by the king (and planned below the Throne Hall) was not realised any more than the so-called Knights' Bath, which, modelled after the Knights' Bath in the Wartburg, was intended to render homage to the knights' cult as a medieval baptism bath. A Bride Chamber in the Bower (after a location in Lohengrin),[23] guest rooms in the first and second floor of the Palas and a great banquet hall were further abandoned projects.[33] In fact, a complete development of Neuschwanstein had never even been planned, and at the time of the king's death there was not a utilisation concept for numerous rooms.[29]

Neuschwanstein was still incomplete when Ludwig II died in 1886. The king never intended to make the palace accessible to the public.[30] No more than six weeks after the king's death, however, the regent Luitpold ordered the palace opened to paying visitors. The administrators of Ludwig's estate managed to balance the construction debts by 1899.[42] From then until World War I, Neuschwanstein was a stable and lucrative source of revenue for the House of Wittelsbach, indeed Ludwig's castles were probably the single largest income source earned by the Bavarian royal family in the last years prior to 1914. To guarantee a smooth course of visits, some rooms and the court buildings were finished first. Initially the visitors were allowed to move freely in the palace, causing the furniture to wear quickly.

When Bavaria became a republic in 1918, the government socialised the civil list. The resulting dispute with the House of Wittelsbach led to a split in 1923: Ludwig's palaces including Neuschwanstein fell to the state and are now managed by the Bavarian Palace Department, a division of the Bavarian finance ministry. Nearby Hohenschwangau Castle fell to the Wittelsbacher Ausgleichsfonds, whose revenues go to the House of Wittelsbach.[43] The visitor numbers continued to rise, reaching 200,000 in 1939.[43]

World War II

Due to its secluded location, the palace survived the destruction of two World Wars. Until 1944, it served as a depot for Nazi plunder that was taken from France by the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Institute for the Occupied Territories (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg für die besetzten Gebiete), a suborganisation of the Nazi Party.[44] The castle was used to catalogue the works of arts. (After World War II 39 photo albums were found in the palace documenting the scale of the art seizures. The albums are now stored in the United States National Archives.[45])

In April 1945, the SS considered blowing up the palace to prevent the building itself and the artwork it contained from falling to the enemy.[46] The plan was not realised by the SS-Gruppenführer who had been assigned the task, however, and at the end of the war the palace was surrendered undamaged to representatives of the Allied forces.[46] Thereafter the Bavarian archives used some of the rooms as a provisional store for salvaged archivalia, as the premises in Munich had been bombed.[47]

Architecture

The effect of the Neuschwanstein ensemble is highly stylistic, both externally and internally. The king's influence is apparent throughout, and he took a keen personal interest in the design and decoration. An example can be seen in his comments, or commands, regarding a mural depicting Lohengrin in the Palas; "His Majesty wishes that ... the ship be placed further from the shore, that Lohengrin's neck be less tilted, that the chain from the ship to the swan be of gold and not of roses, and finally that the style of the castle shall be kept medieval."[48]

The suite of rooms within the Palas contains the Throne Room, Ludwig's suite, the Singers' Hall, and the Grotto. The interior and especially the throne room Byzantine-Arab construction resumes to the chapels and churches of the royal Sicilian Norman-Swabian period in Palermo related to the kings of Germany House of Hohenstaufen. Throughout, the design pays homage to the German legends of Lohengrin, the Swan Knight. Hohenschwangau, where Ludwig spent much of his youth, had decorations of these sagas. These themes were taken up in the operas of Richard Wagner. Many rooms bear a border depicting the various operas written by Wagner, including a theatre permanently featuring the set of one such play. Many of the interior rooms remain undecorated, with only 14 rooms finished before Ludwig's death. With the palace under construction at the king's death, one of the major features of the palace remained unbuilt. A massive keep, which would have formed the highest point and central focus of the ensemble, was planned for the middle of the upper courtyard but was never built, at the decision of the King's family. The foundation for the keep is visible in the upper courtyard.[49]

Neuschwanstein Castle consists of several individual structures which were erected over a length of 150 metres on the top of a cliff ridge. The elongate building is furnished with numerous towers, ornamental turrets, gables, balconies, pinnacles and sculptures. Following Romanesque style, most window openings are fashioned as bi- and triforia. Before the backdrop of the Tegelberg and the Pöllat Gorge in the south and the Alpine foothills with their lakes in the north, the ensemble of individual buildings provides varying picturesque views of the palace from all directions. It was designed as the romantic ideal of a knight's castle. Unlike "real" castles, whose building stock is in most cases the result of centuries of building activity, Neuschwanstein was planned from the inception as an intentionally asymmetric building, and erected in consecutive stages.[33] Typical attributes of a castle were included, but real fortifications – the most important feature of a medieval aristocratic estate – were dispensed with.

Exterior

The palace complex is entered through the symmetrical Gatehouse flanked by two stair towers. The eastward-pointing gate building is the only structure of the palace whose wall area is fashioned in high-contrast colours; the exterior walls are cased with red bricks, the court fronts with yellow limestone. The roof cornice is surrounded by pinnacles. The upper floor of the Gatehouse is surmounted by a crow-stepped gable and held Ludwig II's first lodging at Neuschwanstein, from which he occasionally observed the building work before the hall was completed. The ground floors of the Gatehouse were intended to accommodate the stables.

The passage through the Gatehouse, crowned with the royal Bavarian coat of arms, leads directly into the courtyard. The courtyard has two levels, the lower one being defined to the east by the Gatehouse and to the north by the foundations of the so-called Rectangular Tower and by the gallery building. The southern end of the courtyard is open, imparting a view of the surrounding mountain scenery. At its western end, the courtyard is delimited by a bricked embankment, whose polygonally protracting bulge marks the choir of the originally projected chapel; this three-nave church, never built, was intended to form the base of a 90-metre (295-ft) keep, the planned centrepiece of the architectural ensemble. A flight of steps at the side gives access to the upper level.

Today, the foundation plan of the chapel-keep is marked out in the upper-courtyard pavement. The most striking structure of the upper court level is the so-called Rectangular Tower (45 metres or 148 feet). Like most of the court buildings, it mostly serves a decorative purpose as part of the ensemble. Its viewing platform provides a vast view over the Alpine foothills to the north. The northern end of the upper courtyard is defined by the so-called Knights' House. The three-storey building is connected to the Rectangular Tower and the Gatehouse by means of a continuous gallery fashioned with a blind arcade. From the point of view of castle romanticism the Knights' House was the abode of a stronghold's menfolk; at Neuschwanstein, estate and service rooms were envisioned here. The Bower, which complements the Knights' House as the "ladies' house" but was never used as such, defines the south side of the courtyard. Both structures together form the motif of the Antwerp Castle featuring in the first act of Lohengrin. Embedded in the pavement is the floor plan of the planned palace chapel.

The western end of the courtyard is delimited by the Palas (hall). It constitutes the real main and residential building of the castle and contains the king's stateroom and the servants' rooms. The Palas is a colossal five-story structure in the shape of two huge cuboids that are connected in a flat angle and covered by two adjacent high gable roofs. The building's shape follows the course of the ridge. In its angles there are two stair towers, the northern one surmounting the palace roof by several storeys with its height of 65 metres (213 ft). With their polymorphic roofs, both towers are reminiscent of the Château de Pierrefonds. The western Palas front supports a two-storey balcony with view on the Alpsee, while northwards a low chair tower and the conservatory protract from the main structure. The entire Palas is spangled with numerous decorative chimneys and ornamental turrets, the court front with colourful frescos. The court-side gable is crowned with a copper lion, the western (outward) gable with the likeness of a knight.

Interior

Had it been completed, the palace would have had more than 200 interior rooms, including premises for guests and servants, as well as for service and logistics. Ultimately, no more than about 15 rooms and halls were finished.[50] In its lower stories the Palas accommodates administrative and servants' rooms and the rooms of today's palace administration. The king's staterooms are situated in the upper stories: The anterior structure accommodates the lodgings in the third floor, above them the Hall of the Singers. The upper floors of the west-facing posterior structure are filled almost completely by the Throne Hall. The total floor space of all floors amounts to nearly 6,000 square metres (65,000 sq ft).[50]

Neuschwanstein houses numerous significant interior rooms of German historicism. The palace was fitted with several of the latest technical innovations of the late 19th century.[22][51] Among other things it had a battery-powered bell system for the servants and telephone lines. The kitchen equipment included a Rumford oven that turned the skewer with its heat and so automatically adjusted the turning speed. The hot air was used for a calorifère central heating system.[52] Further novelties for the era were running warm water and toilets with automatic flushing.

The largest room of the palace by area is the Hall of the Singers, followed by the Throne Hall. The 27-by-10-metre (89 by 33 ft)[53] Hall of the Singers is located in the eastern, court-side wing of the Palas, in the fourth floor above the king's lodgings. It is designed as an amalgamation of two rooms of the Wartburg: The Hall of the Singers and the Ballroom. It was one of the king's favourite projects for his palace.[54] The rectangular room was decorated with themes from Lohengrin and Parzival. Its longer side is terminated by a gallery that is crowned by a tribune, modelled after the Wartburg. The eastern narrow side is terminated by a stage that is structured by arcades and known as the Sängerlaube. The Hall of the Singers was never designed for court festivities of the reclusive king. Rather, like the Throne Hall it served as a walkable monument in which the culture of knights and courtly love of the Middle Ages was represented. The first performance in this hall took place in 1933: A concert commemorating the 50th anniversary of Richard Wagner's death.[34]

The Throne Hall, 20 by 12 metres (66 by 39 ft),[55] is situated in the west wing of the Palas. With its height of 13 metres (43 ft)[55] it occupies the third and fourth floors. Julius Hofmann modelled it after the Allerheiligen-Hofkirche in the Munich Residenz. On three sides it is surrounded by colorful arcades, ending in an apse that was intended to hold Ludwig's throne – which was never completed. The throne dais is surrounded by paintings of Jesus, the Twelve Apostles and six canonised kings. The mural paintings were created by Wilhelm Hauschild. The floor mosaic was completed after the king's death. The chandelier is fashioned after a Byzantine crown. The Throne Hall makes a sacral impression. Following the king's wish, it amalgamated the Grail Hall from Parzival with a symbol of the divine right of kings,[19] an incorporation of unrestricted sovereign power, which Ludwig as the head of a constitutional monarchy no longer held. The union of the sacral and regal is emphasised by the portraits in the apse of six canonised kings: Saint Louis of France, Saint Stephen of Hungary, Saint Edward the Confessor of England, Saint Wenceslaus of Bohemia, Saint Olaf of Norway and Saint Henry, Holy Roman Emperor.

- Palace rooms (late 19th century Photochrom prints)

Hall of the Singers

Hall of the Singers Throne Hall

Throne Hall Drawing room

Drawing room Study room

Study room Dining room

Dining room Bedroom

Bedroom

Apart from the large ceremonial rooms several smaller rooms were created for use by Ludwig II.[41] The royal lodging is on the third floor of the palace in the east wing of the Palas. It consists of eight rooms with living space and several smaller rooms. In spite of the gaudy décor, the living space with its moderate room size and its sofas and suites makes a relatively modern impression on today's visitors. Ludwig II did not attach importance to representative requirements of former times, in which the life of a monarch was mostly public. The interior decoration with mural paintings, tapestry, furniture and other handicraft generally refers to the king's favourite themes: the grail legend, the works of Wolfram von Eschenbach, and their interpretation by Richard Wagner.

The eastward drawing room is adorned with themes from the Lohengrin legend. The furniture – sofa, table, armchairs and seats in a northward alcove – is comfortable and homelike. Next to the drawing room is a little artificial grotto that forms the passage to the study. The unusual room, originally equipped with an artificial waterfall and a so-called rainbow machine, is connected to a little conservatory. Depicting the Hörselberg grotto, it relates to Wagner's Tannhäuser, as does the décor of the adjacent study. In the park of Linderhof Palace the king had installed a similar grotto of greater dimensions. Opposite the study follows the dining room, adorned with themes of courtly love. Since the kitchen in Neuschwanstein is situated three stories below the dining room, it was impossible to install a wishing table (dining table disappearing by means of a mechanism) as at Linderhof Palace and Herrenchiemsee. Instead, the dining room was connected with the kitchen by means of a service lift.

The bedroom adjacent to the dining room and the subsequent house chapel are the only rooms of the palace that remain in neo-Gothic style. The king's bedroom is dominated by a huge bed adorned with carvings. Fourteen carvers worked more than four years on the bed canopy with its numerous pinnacles and on the oaken panellings.[56] It was in this room that Ludwig was arrested in the night from 11 to 12 June 1886. The adjacent little house chapel is consecrated to Saint Louis, after whom the owner was named.

The servants' rooms in the basement of the Palas are quite scantily equipped with massive oak furniture. Besides one table and one cabinet there are two beds of 1.80 metres (5 ft 11 in) length each. Opaque glass windows separated the rooms from the corridor that connects the exterior stairs with the main stairs, so that the king could enter and leave unseen. The servants were not allowed to use the main stairs, but were restricted to the much narrower and steeper servants' stairs.

Tourism

Neuschwanstein welcomes almost 1.5 million visitors per year making it one of the most popular tourist destinations in Europe.[3][57] For security reasons the palace can only be visited during a 35-minute guided tour, and no photography is allowed inside the castle. There are also special guided tours that focus on specific topics. In the peak season from June until August, Neuschwanstein has as many as 6000 visitors per day, and guests without advance reservation may have to wait several hours. Those without tickets may still walk the long driveway from the base to the top of the mountain and visit the grounds and courtyard without a ticket, but will not be admitted to the interior of the castle. Ticket sales are processed exclusively via the ticket centre in Hohenschwangau.[58] As of 2008, the total number of visitors was more than 60 million. In 2004, the revenues were booked as €6.5 million.[1]

In culture, art, and science

Neuschwanstein is a global symbol of the era of Romanticism. The palace has appeared prominently in several movies such as Helmut Käutner's Ludwig II (1955) and Luchino Visconti's Ludwig (1972), both biopics about the king; the musical Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) and the war drama The Great Escape (1963). It served as the inspiration for Disneyland's Sleeping Beauty Castle and later similar structures.[59][60] It is also visited by the character Grace Nakimura alongside Herrenchiemsee in the game The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery (1996).

In 1977, Neuschwanstein Castle became the motif of a West German definitive stamp, and it appeared on a €2 commemorative coin for the German Bundesländer series in 2012. In 2007, it was a finalist in the widely publicised on-line selection of the New Seven Wonders of the World.[61]

A meteorite that reached Earth spectacularly on 6 April 2002, at the Austrian border near Hohenschwangau was named Neuschwanstein after the palace. Three fragments were found: Neuschwanstein I (1.75 kg (3.9 lb), found July 2002) and Neuschwanstein II (1.63 kg (3.6 lb), found May 2003) on the German side, and Neuschwanstein III (2.84 kg (6.3 lb), found June 2003) on the Austrian side near Reutte.[62] The meteorite is classified as an enstatite chondrite with unusually large proportions of pure iron (29%), enstatite and the extremely rare mineral sinoite (Si2N2O).[63]

World Heritage candidature

Since 2015, Neuschwanstein and Ludwig's Linderhof and Herrenchiemsee palaces are on the German tentative list for a future designation as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. A joint candidature with other representative palaces of the romantic historicism is discussed (including Schwerin Palace, for example).[64]

Panoramas

Notes

- German: Burg Schwanstein literally translates as Swanstone Castle.

- Vorderhohenschwangau Castle (German: Burg Vorderhohenschwangau) and Hinterhohenschwangau Castle (German: Burg Hinterhohenschwangau) were collectively referred to as Hohenschwangau Castle (German: Burg Hohenschwangau). Confusingly, the neo-Gothic palace built by Ludwig's father is known in English under the same name; in German, it is called Hohenschwangau Palace (German: Schloß Hohenschwangau). An approximate literal translation of Hohenschwangau is High Swan District, but Gau refers to a large unforested area. The prefixes Vorder- and Hinter- identify "front" and "back" of the ensemble.

- The journeys fell into the period of the homosexual king's engagement with his cousin Sophie in Bavaria, which was announced in January and dissolved by Ludwig in October.

- In the revolution of 1848 and after a scandalous affair with Lola Montez, King Ludwig I of Bavaria had to abdicate in favour of his son Maximilian.

- The former queen resided in Hohenschwangau Castle. The two had a strained relationship, at least in part because Marie disapproved of Wagner.

- In November 1870 Ludwig signed the Kaiserbrief, a letter drafted by Bismarck to the other sovereigns of the German states, asking them to crown the Prussian King Wilhelm I as Kaiser. In return, Ludwig received secret payments out of Bismarck's secret account, the Welfenfonds.

Citations

- Bayerisches Staatsministerium der Finanzen 2005

- Bayerisches Staatsministerium der Finanzen 2008

- McIntosh, Christopher (2012). The Swan King: Ludwig II of Bavaria (Illustrated ed.). I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-847-3.

- Buchali 2009

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 4

- Rauch 1991, p. 8

- Blunt 1970, p. 110

- Petzet & Hojer 1995, p. 46

- Pevsner, Honour & Fleming 1992, p. 168

- Petzet & Bunz 1995, p. 50

- Petzet & Bunz 1995, p. 51

- Blunt 1970, p. 197

- "Neuschwanstein Castle: Idea and History". Bavarian Palace Department. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- Petzet & Bunz 1995, p. 53

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 10

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 12

- Rauch 1991, p. 12

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 16

- Petzet & Bunz 1995, p. 7

- Petzet & Bunz 1995, p. 82

- Blunt 1970, p. 212

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 9

- Ammon 2007, p. 107

- Blunt 1970, p. 114

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 11

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 21

- Petzet & Bunz 1995, p. 64

- Rauch 1991, p. 14

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 19

- Petzet & Bunz 1995, p. 67

- Merkle 2001, p. 68

- Rauch 1991, p. 13

- Linnenkamp 1986, p. 171

- Petzet & Bunz 1995, p. 65

- Bitterauf 1910

- "Ludwig II. (Bayern)" (in German). Who's Who Online. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- Blunt 1970, p. 111

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 23

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 22

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 26

- Rauch 1991, p. 16

- Sykora 2004, p. 32f

- Farmer 2002, pp. 140f

- National Archives 2007

- Linnenkamp 1986, pp. 184f

- https://www.dw.com/en/neuschwanstein-a-fairy-tale-darlings-dark-nazi-past/a-17442885 DW

- http://capa.conncoll.edu/peters.ludwig.html Conncoll

- Desing 1992

- Parkyn 2002, p. 117

- "Neuschwanstein Castle: Interior and modern technology". Bavarian Palace Department. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- Linnenkamp 1986, pp. 64, 84

- Koch von Berneck 1887, p. 47 (measurements do not take into account gallery and Sängerlaube)

- Petzet & Hojer 1991, p. 48

- Koch von Berneck 1887, p. 45

- Blunt 1970, p. 113

- "Neuschwanstein Castle remains the biggest tourist magnet in Bavaria". www.themayor.eu. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- "Ticketcentre Hohenschwangau". Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- Imagineers (1998). Walt Disney Imagineering: A Behind the Dreams Look At Making the Magic Real. Disney Editions. ISBN 0-7868-8372-3.

- Smith, Alex (2008). Is Authenticity Important? (MA thesis). Royal College of Art. p. 79.

- Hatton 2007

- Heinlein 2004, p. 17

- Heinlein 2004, p. 29

- Biedermann 2009

General sources

- Ammon, Thomas (2007), Ludwig II. für Dummies: Der Märchenkönig—Zwischen Wahn, Wagner und Neuschwanstein, Wiley-VCH, ISBN 978-3-527-70319-7

- "Faltlhauser begrüßte 50-millionsten Besucher im Schloss Neuschwanstein" [Faltlhauser welcomed the 50 millionth visitor in Neuschwanstein Castle] (Press release) (in German). Bayerisches Staatsministerium der Finanzen. 27 July 2005. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- "Neue Homepage für Schloss Neuschwanstein in fünf Sprachen" [New website for Neuschwanstein Castle in five languages] (Press release) (in German). Bayerisches Staatsministerium der Finanzen. 28 July 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- "Pschierer: Schloss Neuschwanstein ist heute eine weltweite Premiummarke" [Pschierer: Neuschwanstein Castle today is a global premium brand] (Press release) (in German). Bayerisches Staatsministerium der Finanzen. 19 September 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- Neuschwanstein Castle: Official Guide, Munich: Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen, 2004

- Biedermann, Henning (April 2009), Neuschwanstein auf dem Weg zum Weltkulturerbe? Noch mehr Ruhm—noch mehr Schutz für das Königsschloss, Bayerisches Fernsehen, archived from the original on 20 April 2009

- Bitterauf, Theodor (1910), "Ludwig II. (König von Baiern)", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), 55, pp. 540–555(German WikiSource)

- Blunt, Wilfried (1970), Ludwig II.: König von Bayern, Heyne, ISBN 978-3-453-55006-3

- Blunt, Wilfred (1973), The Dream King: Ludwig II of Bavaria, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-003606-0

- Buchali, Frank (2009). "Schwangau: Neuschwanstein – Traumschloss als Postkartenmotiv" (pdf) (in German). burgen-web.de. Retrieved 30 September 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Desing, Julius (1992), Royal Castle Neuschwanstein, Kienberger

- Farmer, Walter I. (2002), Die Bewahrer des Erbes: Das Schicksal deutscher Kulturgüter am Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges, Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-89949-010-7

- Hatton, Barry (29 July 2007). "New 7 wonders of the world are named". Deseret News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heinlein, Dieter (2004), Die Feuerkugel vom 6. April 2002 und der sensationelle Meteoritenfall "Neuschwanstein", Augsburg

- Koch von Berneck, Max (1887), München und die Königsschlösser Herrenchiemsee, Neuschwanstein, Hohenschwangau, Linderhof und Berg, Zürich: Caesar Schmidt

- Linnenkamp, Rolf (1986), Die Schlösser und Projekte Ludwigs II., ISBN 978-3-453-02269-0

- Merkle, Ludwig (2001), Ludwig II. und seine Schlösser, Stiebner, ISBN 978-3-8307-1024-0

- "National Archives Announces Discovery of "Hitler Albums" Documenting Looted Art" (Press release). National Archives. 1 November 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- Petzet, Michael; Bunz, Achim (1995), Gebaute Träume: Die Schlösser Ludwigs II. von Bayern, Hirmer, pp. 46–123, ISBN 978-3-7774-6600-2

- Parkyn, Neil (2002), Siebzig Wunderwerke der Architektur, zweitausendeins, ISBN 978-3-86150-454-2

- Petzet, M.; Hojer, G. (1991), Amtlicher Führer Schloss Neuschwanstein, Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (1992), Lexikon der Weltarchitektur, Prestel, ISBN 3-7913-2095-5

- Rauch, Alexander (1991), Neuschwanstein, Atlantis Verlag, ISBN 978-3-88199-874-1

- Schlim, Jean Louis (2001), Ludwig II.: Traum und Technik, Buchendorfer Verlag, ISBN 978-3-934036-52-9

- Schröck, Rudolf (November 2007), "Madness in Bavaria", The Atlantic Times

- Smith, Alex (2008), Is Authenticity Important?, Royal College of Art, retrieved 30 January 2011

- Spangenberg, Marcus (1999), The Throne Room in Schloss Neuschwanstein: Ludwig II of Bavaria and his Vision of Divine Right, Schnell & Steiner, ISBN 978-3-7954-1233-3

- Sykora, Katharina (2004), "Ein Bild von einem Mann". Ludwig II. von Bayern: Konstruktion und Rezeption eines Mythos, Campus Verlag, ISBN 978-3-593-37479-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neuschwanstein Castle. |

- Official website.

- Neuschwanstein Pictures: From a visitor's perspective.

- Neuschwanstein Castle on Bavarian Palace Department website.

- Floor Plan All floors.

- Webcam.

- Many 360° panoramas, with locations on three floor plans on ZDF site (requires Flash version 9 or higher).

- Several 360° panoramas (requires QuickTime VR).