Nat Turner's slave rebellion

Nat Turner's Rebellion (also known as the Southampton Insurrection) was a slave rebellion that took place in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831,[3] led by Nat Turner. Rebel slaves killed from 55 to 65 people, at least 51 being white.[4] The rebellion was put down within a few days, but Turner survived in hiding for more than two months afterwards. The rebellion was effectively suppressed at Belmont Plantation on the morning of August 23, 1831.[5]

| Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the prelude to the American Civil War and North American slave revolts | |||||||

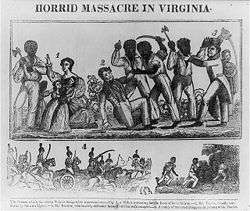

1831 woodcut illustrating various stages of the rebellion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rebel slaves | Local white militias | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Nat Turner | Unknown, likely many | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Approximately 160 killed or executed by militia and mobs[1][2] | 55–65 killed | ||||||

| North American slave revolts |

|---|

Toussaint Louverture |

|

|

There was widespread fear in the aftermath, and white militias organized in retaliation in opposition to the slaves. The state executed 56 slaves accused of being part of the rebellion, and many non-participant slaves were punished in the frenzy. Approximately 120 slaves and free blacks were murdered by militias and mobs in the area.[1][2] State legislatures passed new laws prohibiting education of slaves and free black people,[6] restricting rights of assembly and other civil liberties for free black people, and requiring white ministers to be present at all worship services.

Nat Turner's background

Nat Turner was an American slave who had lived his entire life in Southampton County, Virginia, an area with more blacks than whites.[7] After the rebellion, a reward notice described him as:

5 feet 6 or 8 inches [168–173 cm] high, weighs between 150 and 160 pounds [68–73 kg], rather "bright" [light-colored] complexion, but not a mulatto, broad shoulders, larger flat nose, large eyes, broad flat feet, rather knockneed, walks brisk and active, hair on the top of the head very thin, no beard, except on the upper lip and the top of the chin, a scar on one of his temples, also one on the back of his neck, a large knot on one of the bones of his right arm, near the wrist, produced by a blow.[8]

Turner was intelligent and learned how to read and write at a young age. He grew up deeply religious and was often seen fasting, praying, or immersed in reading the stories of the Bible.[9] He frequently had visions which he interpreted as messages from God, and these visions influenced his life. He ran away at age 21 from his owner Samuel Turner, but he returned a month later after becoming delirious from hunger and receiving a vision which told him to "return to the service of my earthly master".[10] He had his second vision in 1824 while working in the fields under his new owner Thomas Moore. In it, "the Saviour was about to lay down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and the great day of judgment was at hand".[11] Turner often conducted Baptist services and preached the Bible to his fellow slaves, who dubbed him "the Prophet".

By the spring of 1828, Turner was convinced that he "was ordained for some great purpose in the hands of the Almighty".[10] He "heard a loud noise in the heavens" while working in his owner's fields on May 12, "and the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the Serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first".[12]

In 1830, Joseph Travis purchased Turner, and Turner later recalled that he was "a kind master" who had "placed the greatest confidence in" him.[12] Turner eagerly anticipated God's signal to "slay my enemies with their own weapons".[12] He witnessed a solar eclipse on February 12, 1831 and was convinced that it was the sign for which he was waiting, so he started preparations for an uprising against the white slaveholders of Southampton County by purchasing muskets. He "communicated the great work laid out to do, to four in whom I had the greatest confidence", his fellow slaves Henry, Hark, Nelson, and Sam.[12]

Turner's Rebellion

Turner originally planned to begin the rebellion on July 4, 1831, but he had fallen ill.[13] An atmospheric disturbance on August 13 made the sun appear bluish-green; he took it as the final signal and began the rebellion a week later, on August 21. He started with several trusted fellow slaves, and ultimately gathered more than 70 enslaved and free blacks, some of whom were on horseback.[14] The rebels traveled from house to house, freeing slaves and killing all the white people whom they encountered.

Muskets and firearms were too difficult to collect and would gather unwanted attention, so the rebels used knives, hatchets, axes, and blunt instruments. Historian Stephen B. Oates states that Turner called on his group to "kill all the white people".[15] A newspaper noted, "Turner declared that 'indiscriminate slaughter was not their intention after they attained a foothold, and was resorted to in the first instance to strike terror and alarm.'"[16] The group spared a few homes "because Turner believed the poor white inhabitants 'thought no better of themselves than they did of negroes.'"[15] The rebels killed approximately 60 white people before they were defeated.[15] Of the total killed, many were women and children. Eventually, the state militia infantry were able to defeat the insurrection with twice the manpower of the rebels, reinforced by three companies of artillery.[17]

Retaliation

Within a day of the suppression of the rebellion, the local militia and three companies of artillery were joined by detachments of men from the USS Natchez and USS Warren, which were anchored in Norfolk, and militias from counties in Virginia and North Carolina surrounding Southampton.[17] The state executed 56 black people, and militias killed at least 100 more.[18] An estimated 120 black people were killed, most of whom were not involved with the rebellion.[1][2]

Rumors quickly spread among whites that the slave revolt was not limited to Southampton and that it had spread as far south as Alabama. Fears led to reports in North Carolina that "armies" of slaves were seen on highways, and that they had burned and massacred the white inhabitants of Wilmington, North Carolina, and were marching on the state capital.[15] Such fear and alarm led to whites' attacking blacks throughout the South with flimsy cause; the editor of the Richmond Whig described the scene as "the slaughter of many blacks without trial and under circumstances of great barbarity".[19] The white violence against the black people continued two weeks after the rebellion had been suppressed. General Eppes ordered troops and white citizens to stop the killing:

He will not specify all the instances that he is bound to believe have occurred, but pass in silence what has happened, with the expression of his deepest sorrow, that any necessity should be supposed to have existed, to justify a single act of atrocity. But he feels himself bound to declare, and hereby announces to the troops and citizens, that no excuse will be allowed for any similar acts of violence, after the promulgation of this order.[20]

Reverend G. W. Powell wrote a letter to the New York Evening Post stating that "many negroes are killed every day. The exact number will never be known."[21] A company of militia from Hertford County, North Carolina, reportedly killed 40 blacks in one day and took $23 and a gold watch from the dead.[22] Captain Solon Borland led a contingent from Murfreesboro, North Carolina, and he condemned the acts "because it was tantamount to theft from the white owners of the slaves".[22] Blacks suspected of participating in the rebellion were beheaded by the militia, and "their severed heads were mounted on poles at crossroads as a grisly form of intimidation".[22] A section of Virginia State Route 658 remains labeled as "Blackhead Signpost Road" in reference to these events.[23]

Aftermath

Turner eluded capture for six weeks but remained in Southampton County. On October 30, a white farmer named Benjamin Phipps discovered him hidden among the local Nottoway people, in a depression in the earth, created by a large, fallen tree that was covered with fence rails. He was tried on November 5, 1831 for "conspiring to rebel and making insurrection"; he was convicted and sentenced to death.[24][25] He was asked if he regretted what he had done, and he responded, "Was Christ not crucified?"[13] He was hanged on November 11 in Jerusalem, Virginia, and his corpse was drawn and quartered.[26]

After Turner's capture, lawyer Thomas Ruffin Gray published The Confessions of Nat Turner: The Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton, Virginia. The book was the result of Gray's research while Turner was in hiding and his conversations with Turner before the trial, and it is the primary window into Turner's mind. Gray had a conflict of interest because he was the defense attorney for other accused participants, so historians disagree on how to assess it as insight into Turner.

Legal response

In the aftermath of the rebellion, dozens of suspected rebels were tried in courts called specifically for the purpose of hearing the cases against the slaves. Most of the trials took place in Southampton, but some were held in neighboring Sussex County plus a few in other counties. Most slaves were found guilty and many were then executed, while others were transported outside the state but not executed; 15 of the slaves tried in Southampton were acquitted.[27] Moreover, some slave owners sought compensation from the legislature for slaves who were killed without trial during the rebellion or its immediate aftermath; all their petitions were rejected.[28]

The Virginia General Assembly debated the future of slavery the following spring; some urged gradual emancipation, but the pro-slavery side prevailed. The General Assembly passed legislation making it unlawful to teach reading and writing to slaves, free blacks, or mulattoes, and restricting all blacks from holding religious meetings without the presence of a licensed white minister.[29] Other slave-holding states in the South enacted similar laws restricting activities of slaves and free blacks.[30]

Some free blacks chose to move their families north to obtain educations for their children. Some white people, such as teachers Thomas J. Jackson (later to be famous in the American Civil War as Gen. "Stonewall" Jackson) and Mary Smith Peake, and George H. Thomas (a future Union general and child at the time of his doing this) violated the laws and taught slaves to read. Overall, the laws enacted in the aftermath of the Turner Rebellion enforced widespread illiteracy among slaves. As a result, most newly freed slaves and many free blacks in the South were illiterate at the end of the American Civil War.

Freedmen and Northerners considered the issue of education and helping former slaves gain literacy as one of the most critical in the postwar South. Consequently, many Northern religious organizations, former Union Army officers and soldiers, and wealthy philanthropists were inspired to create and fund schools for the betterment of African Americans in the South. Although Reconstruction legislatures passed authorization to establish public education for the first time in the South, a system of legal racial segregation was later imposed under Jim Crow laws, and black schools were systematically underfunded by Southern states.

See also

- History of slavery in the United States

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- The Birth of a Nation (2016 film)

- The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967 novel by William Styron)

References

- Breen 2015, pp. 98, 231.

- Breen 2015, Chapter 9 and Allmendinger 2014, Appendix F are recent studies which review various estimates for the number of slaves and free blacks killed without trial, giving a range of from 23 killed to over 200 killed; Breen notes on page 231 that "high estimates have been widely accepted in both academic and popular sources".

- Frederic D. Schwarz Archived December 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine "1831: Nat Turner's Rebellion," American Heritage, August/September 2006.

- "Nat Turner - Black History - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (July 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Belmont" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- Gray-White, Deborah; Bay, Mia; Martin Jr, Waldo E. (2013). Freedom on my mind: A History of African Americans. New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2013. p. 225.

- Drewry, William Sydney (1900). The Southampton Insurrection. Washington, D. C.: The Neale Company. p. 108.

- Description of Turner included in a $500 reward notice in the Washington National Intelligencer on September 24, 1831.

- Aptheker (1993), p. 295.

- Gray (1831), p. 9.

- Gray (1831), p. 10.

- Gray (1831), p. 11.

- Foner, Eric (2014). An American History: Give Me Liberty. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 336. ISBN 9780393920338.

- Aptheker, Herbert (1983). American Negro Slave Revolts (6th ed.). New York: International Publishers. p. 298. ISBN 0-7178-0605-7.

- Oates, Stephen (October 1973). "Children of Darkness". American Heritage. 24 (6). Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- Richmond Enquirer, November 8, 1831, quoted in Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts, p. 299. Aptheker notes that the Enquirer was "hostile to the cause Turner espoused." p. 298.

- Aptheker (1993), p. 300.

- Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts, p. 301, citing the Huntsville, Alabama, Southern Advocate, October 15, 1831.

- Richmond Whig, September 3, 1831, quoted in Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts, p. 301.

- Richmond Enquirer, September 6, 1831, quoted in Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts, p. 301.

- New York Evening Post, September 5, 1831, quoted in Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts, p. 301.

- Dr. Thomas C., Parramore (1998). Trial Separation: Murfreesboro, North Carolina and the Civil War. Murfreesboro, North Carolina: Murfreesboro Historical Association, Inc. p. 10. LCCN 00503566.

- Marable, Manning (2006), Living Black History.

- Southampton Co., VA, Court Minute Book 1830-1835, pp. 121–23.

- "Proceedings on the Southampton Insurrection, Aug-Nov 1831"

- Gibson, Christine (November 11, 2005). "Nat Turner, Lightning Rod". American Heritage Magazine. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- Alfred L. Brophy, "The Nat Turner Trials", North Carolina Law Review (June 2013), volume 91: 1817–80.

- Brophy (2013), pp. 1831–1835.

- Virginia: A Guide to the Old Dominion (1992), p. 78

- Lewis, Rudolph. "Up From Slavery: A Documentary History of Negro Education". ChickenBones: A Journal for Literary & Artistic African-American Themes. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

Sources

- Herbert Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts. 5th edition. New York, NY: International Publishers, 1983 (1943).

- Kim Warren, "Literacy and Liberation," Reviews in American History Volume 33, Number 4, December 2005, Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press

- Virginia Writers' Program, Virginia: A Guide to the Old Dominion, Richmond, VA: Virginia State Library, reprint, 1992. ISBN 0-88490-173-4.

Further reading

| Library resources about Nat Turner's slave rebellion |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nat Turner |

- Higginson, Thomas Wentwworth (August 1861). "Nat Turner's Insurrection". The Atlantic.

- Greenberg, Kenneth S., ed. (1996). The confessions of Nat Turner and related documents. Bedford Books. ISBN 0312160518.

- Digital Library on American Slavery, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2015.

- David F. Allmendinger Jr. Nat Turner and the Rising in Southampton County. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

- Herbert Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts. 5th edition. New York, NY: International Publishers, 1983 (1943).

- Herbert Aptheker. Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion. New York, NY: Humanities Press, 1966.

- Alfred L. Brophy. " "The Nat Turner Trials" North Carolina Law Review (June 2013), volume 91: 1817–80.

- Patrick H. Breen. The Land Shall Be Deluged in Blood: A New History of the Nat Turner Revolt. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Patrick H. Breen. "Nat Turner's Revolt: Rebellion and Response in Southampton County, Virginia Ph.D. dissertation, University of Georgia, 2005.

- Scot French. The Rebellious Slave: Nat Turner in American Memory. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. 2004.

- William Lloyd Garrison, "The Insurrection," The Liberator (September 3, 1831). A contemporary abolitionist's reaction to news of the rebellion.

- Walter L. Gordon III. The Nat Turner Insurrection Trials: A Mystic Chord Resonates Today (2009). ISBN 978-1-4392-2983-5.

- Thomas R. Gray, The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrections in Southampton, Va. Baltimore, MD: Lucas & Deaver, 1831. HTML edition at Project Gutenberg.

- Kenneth S. Greenberg, ed. Nat Turner: A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Nat Turner Project: A Digital Archive of historical sources related to Nat Turner and the Southampton County slave revolt of 1831 Natturnerproject.org

- Kinohi Nishikawa. "The Confessions of Nat Turner." The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Multiethnic American Literature. Ed. Emmanuel S. Nelson. 5 vols. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005. 497–98.

- Stephen B. Oates, The Fires of Jubilee: Nat Turner's Fierce Rebellion. New York, NY: HarperPerennial, 1990 (1975). ISBN 0-06-091670-2.

- Junius P. Rodriguez, ed. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2006.

- Sharon Ewell Foster. The Resurrection of Nat Turner, Part One, The Witness, A Novel (2011). ISBN 978-1-4165-7803-1.