Moravians

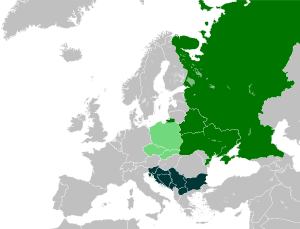

Moravians (Czech: Moravané or colloquially Moraváci, outdated Moravci) are a West Slavic ethnographic group from the Moravia region of the Czech Republic, who speak the Moravian dialects of the Czech language or Common Czech or a mixed form of both. Along with the Silesians of the Czech Republic, a part of the population to identify ethnically as Moravian has registered in Czech censuses since 1991. The figure has fluctuated and in the 2011 census, 6.01%[3] of the Czech population declared Moravian as their ethnicity. Smaller pockets of persons declaring Moravian ethnicity are also native to neighboring Slovakia.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 634,183 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 630,897 (2011)[1] | |

| 2,979 (2018)[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Czech (Moravian dialects), Silesian, Slovak | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Irreligion, Protestantism (Hussitism), Orthodox Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Czechs, Silesians, Poles, Slovaks and other West Slavs | |

Etymology

.svg.png)

A certain ambiguity in the Czech language derives from the fact that it only distinguishes between Čechy (Bohemia) and Česká republika (Czech Republic), but the corresponding adjective český and noun designating an inhabitant and/or a member of a nation Čech can be related to either of the two (the adjective bohémský and the noun bohém have only the "socially unconventional person" meaning).[5]

History

Moravian tribe

The Moravians (Old Slavic self-designation Moravljane,[6] Slovak: Moravania, Czech: Moravané) were a West Slavic tribe in the Early Middle Ages. Although it is not known exactly when the Moravian tribe was founded, Czech historian Dušan Třeštík claimed the tribe was formed between the turn of the 6th century to the 7th century, around the same time as the other Slavic tribes.[7]

In the 9th century Moravians settled mainly around the historic Region of Moravia and Western Slovakia, but also in parts of central-southern Poland, Lower Austria (up to the Danube) and Upper Hungary. The first known mention of the Moravians was in the Annales Regni Francorum in 822 AD. The tribe was located by the Bavarian Geographer between the tribe of the Bohemians and the tribe of the Bulgarians.

In the 9th century Moravians gain control over neighbouring Nitra and founded the Realm of Great Moravia, ruled by the Mojmír dynasty until the 10th century. At times, the empire controlled even other neighboring regions, including Bohemia and parts of present-day Hungary, Poland and Ukraine. It emerged into one of the most powerful states in Central Europe.

After the breakup of the Moravian Realm the Moravian tribe was divided between the new states Duchy of Bohemia and Hungary. The western Moravians were assimilated by the Czechs and presently identify as Czechs. The modern nation of the Slovaks was formed out of the eastern part of the Moravian tribe within the Kingdom of Hungary.[8]

Moravians within the Czech lands

Bretislaus I, Duke of Bohemia, in solving the succession question in his will (he had five sons) decided to completely reorganize Moravia, so that it should be governed by the younger sons of the royal family. It was still considered one country, but from an objective standpoint it was weakened, and Moravia could not lead to the formation of the medieval "nation" as quickly as in Bohemia. The way leading to the differentiation of the Moravians from the Czechs was caused by political and economic changes of the late 12th and early 13th century. Czech historical tradition was grown in Moravia during the Middle Ages, for example Czech Chronicles was reread and distributed.

Moravian ethnicity was declared for the first time in the population census of 1991. After the Velvet Revolution a strong political movement to reinstate the Moravian-Silesian land (země Moravskoslezská in Czech, having been one of the four lands of Czechoslovakia between 1928 and 1939) was active in Moravia. Accordingly, the so far officially united Czech ethnicity was split in line with the historical division of the Czech Republic into Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia (the Czech lands). Part of the Czech speaking inhabitants of Moravia declared Moravian ethnicity and part of the Czech speaking inhabitants of Czech Silesia declared Silesian ethnicity.

1,363,000 citizens of the Czech Republic declared Moravian ethnicity in 1991. However, the number dropped to 380,474 in the 2001 census – many persons previously declaring themselves as Moravians declared themselves again as Czechs in this census. In 2011, the number increased again to 630 897. The strongest sense of patriotism towards Moravia is found in the environs of Brno, the former capital of Moravia.

Only in the first years after the Velvet Revolution in 1989 did a few Moravian political parties seem to be able to gain some success in elections. However they lost much of their strength around the time of the Dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993 when Czechoslovakia peacefully split into the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic.

According to the 2011 Census, the percentage of people without religion was lowest in the Moravian Zlín Region, followed by the partly Bohemian, partly Moravian Vysočina Region, the South Moravian Region, the Moravian-Silesian Region, and the predominantly Moravian Olomouc Region.[9]

See also

- List of Moravians

- Old Salem

References

- Inline citations

- "Bilancia podľa národnosti a pohlavia - SR-oblasť-kraj-okres, m-v [om7002rr]" (in Slovak). Statistics of Slovakia. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- "Výstupní objekt VDB". vdb.czso.cz. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- Havlík, Lubomir Emil (1990). "Symboly moravské identity". Moravskoslezská orlice (in Czech) (14): 12.

- Dictionary of the Standard Czech Language (in Czech)

- Graus 1980, p. 47.

- Třeštík 2008, p. 270.

- Havlík 2013, p. 382.

- Czech Statistical Office: Percentage of population without religious faith as of 26/3/2011, results by permanent residence (in Czech)

- Sources

- Graus, František (1980). Die Nationenbildung der Westslawen im Mittelalter. Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Sigmaringen. ISBN 3-7995-6103-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (German)

- Lubomír E. Havlík: Svatopluk Veliký, král Moravanů a Slovanů [Svatopluk the Great. King of the Moravians and Slavs]. Jota, Brno 1994, ISBN 80-85617-19-6. (Czech)

- Havlík, Lubomír E. (2013). Kronika o Velké Moravě. Jota, o.O. ISBN 978-80-8561-706-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Czech)

- Třeštík, Dušan (2008). Počátky Přemyslovců. Vstup Čechů do dějin (530–935) [The Beginnings of the Přemyslids. The Enter of the Czechs into History (530–935)]. Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, o.O. ISBN 978-80-7106-138-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Czech)

- Dušan Třeštík: Vznik Velké Moravy. Moravané, Čechové a střední Evropa v letech 791–871 [The Founding of Great Moravia. Moravians, Czechs and Middle Europe in the years 791–871]. Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, o.O. 2010, ISBN 978-80-7422-049-4 (Czech)

- Tennent, Gilbert (1743). Some Account of the Principles of the Moravians. Moravians at Google Books