Mongoloid

Mongoloid (/ˈmɒŋ.ɡə.lɔɪd/[1][2]) is a grouping of various people indigenous to East Asia, Central Asia, Southeast Asia, North Asia, Polynesia, and the Americas. It is one of the traditional three races first introduced in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen School of History,[3] the other two groups being Caucasoid and Negroid.[4]

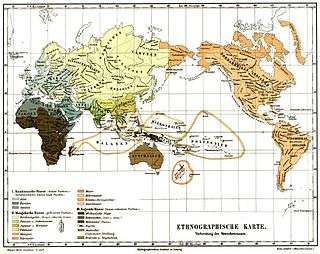

ethnographic map

| Caucasoid: Hamitic Negroid: African Negro Uncertain: | Mongoloid: North Mongol Malay |

Individuals within these populations often share certain associated phenotypic traits, such as epicanthic folds, sino- or sundadonty, shovel-shaped incisors and neoteny. The concept of Mongoloid races is historical referring to a grouping of human beings historically regarded as a biological taxon.

Epicanthic folds and oblique palpebral fissures are common among Mongoloid individuals. Most exhibit the Mongolian spot from birth to about age four years.[5][6] Mongoloids in general have straight, black hair and dark brown almond-shaped eyes, and have relatively flatter faces in comparison to those of Caucasoid and Negroid skulls.[7]

Due to covering a large and diverse population, from Native Americans to Vietnamese, the Mongoloid classification is difficult, but Mongoloids are generally considered to share some similar skeletal and dental features.[8]

The term Mongoloid has had a second usage referencing Down syndrome, now generally regarded as highly offensive.[9][10][11][12] When used in reference to people with Down syndrome, the term "mongol" and related words affect the "...dignity of people of the mongoloid race..."[13] Those affected were often referred to as "Mongoloids" or in terms of "Mongolian idiocy" or "Mongolian imbecility".

Populations

Mongoloids | |

According to historical race concepts, Mongoloid peoples are the most spread out among all human populations since they have stretched almost completely around the earth's surface. From an Asian point of reference, populations range from as far east as Greenland, to as far west as Kalmykia, Crimea, giving Mongoloid peoples or their descendants a historical presence across four continents. According to the Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (1885–90), peoples included in the Mongoloid race are North Mongol, Chinese & Indochinese, Japanese & Korean, Tibetan & Burmese, Malay, Polynesian, Maori, Micronesian, Eskimo, and Native American.[14]

In 1856, the "Mongolian" race, using a narrow definition which did not include either the "Malay" or the "American" races, was the second most populous race in the world behind the Caucasian race.[15] In 1881, the Mongoloid race, using a broad definition which included both Malays and indigenous Americans, was the most populous race on Earth,[16] and it was still the most populous race on Earth in the year 1892, using a narrow definition which did not include either the "Malayan" or the "American" races.[17]

The first use of the term Mongolian race was by Christoph Meiners in 1785, who divided humanity into two races he labeled "Tartar-Caucasians" and "Mongolians".[18]

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach said that he borrowed the term Mongolian from Christoph Meiners to describe the race he designated "second, [which] includes that part of Asia beyond the Ganges and below the river Amoor, which looks toward the south, together with the islands and the greater part of these countries which is now called Australian".[19]

In 1861, Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire added the Australian as a secondary race (subrace) of the principal race of Mongolian.[20] Arthur de Gobineau defined the extent of the Mongolian race, "by the yellow the Altaic, Mongol, Finnish and Tartar branches".[21][22] Later, Thomas Huxley used the term Mongoloid and included American Indians as well as Arctic Native Americans.[23] Other terms were proposed, such as Mesochroi (middle color),[24] but Mongoloid was widely adopted.

In 1909, a map published based on racial classifications conceived by Herbert Hope Risley classified inhabitants of Bengal and parts of Odisha as Mongolo-Dravidians, people of mixed Mongoloid and Dravidian origin.[25] Similarly in 1904, Ponnambalam Arunachalam claimed the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka were a people of mixed Mongolian and Malay racial origins as well as Indo-Aryan, Dravidian and Vedda origins.[26] Howard S. Stoudt in The Physical Anthropology of Ceylon (1961) and Carleton S. Coon in The Living Races of Man (1966) classified the Sinhalese as partly Mongoloid.[27][28] In 1927, Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt classified people from Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, East India, parts of Northeast India, western Myanmar and Sri Lanka as East Brachid, referring to people of mixed Indid and South Mongolid origins.[29] East Brachid is another term for Risley's Mongolo-Dravidian.[30] Eickstedt also classified the people of central Myanmar, Yunnan, southern Tibet, Thailand and parts of India as Palaungid deriving from the name of the Palaung people of Myanmar. The Burmese, Karen, Kachin, Shan, Sri Lankans, Tai, South Chinese, Munda and Juang, among others were classified as having "mixed" with the Palaungid phenotype according to Eickstedt.[31]

In 1940, anthropologist Franz Boas included the American race as part of the Mongoloid race of which he mentioned the Aztecs of Mexico and the Maya of Yucatán.[32] Boas also said that, out of the races of the Old World, the American native had features most similar to the east Asiatic.[32]

In 1981, Elizabeth Smithgall Watts who taught anthropology at Tulane University[33] said that the question of American Indians being a separate race from "Asiatic Mongoloids" is a question of how much genetic difference a population needs from another population to be considered a "major race". She said that even the people who consider American Indians to be a separate race acknowledge that they are genetically closest to "Asians".[34]

In 1983, Douglas J. Futuyma, professor of evolutionary processes at the University of Michigan, said that the inclusion of Native Americans and Pacific Islanders under the Mongoloid race was not recognized by many anthropologists who consider them distinct races.[35]

In 1984, Roger J. Lederer, Professor of Biological Sciences at California State University at Chico,[36] separately listed the Mongoloid race from Pacific islanders and American Indians when he enumerated the "geographical variants of the same species known as races...we recognize several races, Inuit, American Indians, Mongoloid... Polynesian".[37]

In 1995, Dr. Marta Mirazón Lahr of the Department of Biological Anthropology at Cambridge University used the term Mongoloid to refer to Asian populations, Indigenous Australians, Pacific Islanders, Negritos, and Amerindians, classifying Northeast Asians as typical Mongoloids and all other Mongoloid groups as atypical Mongoloids.[38]

Subraces

| Caucasoid | |

| Congoid | |

| Capoid | |

| Mongoloid | |

| Australoid |

In 1900, Joseph Deniker said the "Mongol race admits two varieties or subraces: Tunguse or Northern Mongolian... and Southern Mongolian".[20]

Alfred L. Kroeber (1948), Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, referring to the racial classification of mankind on the basis of physical features, said that there are basically "three grand divisions." Kroeber indicated that, within the three-part classification, the Mongoloid, the Negroid, and the Caucasian are the three "primary racial stocks of mankind." Kroeber said that the following are the divisions of the Mongoloid stock: the "Mongolian proper of East Asia," the "Malaysian of the East Indies," and the "American Indian." Kroeber alternatively referred to the divisions of the Mongoloid stock as the following: "Asiatic Mongoloids," "Oceanic Mongoloids," and "American Mongoloids." Kroeber said that the differences among the three divisions of the Mongoloid stock are not very large. Kroeber said that the Malaysian and the American Indian are generalized type peoples while the Mongolian proper is the most extreme or pronounced form. Kroeber said that the original Mongoloid stock must be regarded as being more like the current Malaysians, the current American Indians, or an intermediate type between these two. Kroeber said that it is from these generalized type peoples, who kept more nearly the ancient type, that peoples such as the Chinese gradually diverged, who added the oblique eye, and a "certain generic refinement of physique." Kroeber said that, according to most anthropometrists, the Eskimo is the most particularized sub-variety out of the American Mongoloids. Kroeber said that in the East Indies, and in particular the Philippines, there can at times be distinguished a less specifically Mongoloid strain, which has been called the "Proto-Malaysian," and a more specifically Mongoloid strain, which has been called the "Deutero-Malaysian." Kroeber said that Polynesians appear to have primary Mongoloid connections by way of the Malaysians. Kroeber said that the Mongoloid element of Polynesians is not a specialized Mongoloid. Kroeber said that the Mongoloid element in Polynesians appears to be larger than the definite Caucasian strain in Polynesians. Speaking of Polynesians, Kroeber said that there are locally possible minor Negroid absorptions, as the ancestral Polynesians had to pass by or through archipelagoes which are presently Papuo-Melanesian Negroid to get to the central Pacific.[39][40]

Archaeologist Peter Bellwood claims that the vast majority of people in Southeast Asia, the region he calls the "clinal Mongoloid-Australoid zone", are Southern Mongoloids but have a high degree of Australoid admixture.[41] However more recent studies find no evidence of a "high degree of Australoid admixture". Southeast Asians are both morphologically and genetically very close to other Mongoloids in East Asia and only some show minor genetic admixture, mostly on their maternal side.[42][43]

Akazawa Takeru, professor of anthropology at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto, said that there are Neo-Mongoloids and Paleo-Mongoloids. Akazawa said Neo-Mongoloids have "extreme Mongoloid, cold-adapted features" and they include the Buryats, Eskimo and Chukchi. In contrast, Akazawa said Paleo-Mongoloids are less cold-adapted. He said Burmese, Filipinos, Polynesians, Jōmon and the indigenous peoples of the Americas were Paleo-Mongoloid.[44]

Human skeletal remains in Southeast Asia show the gradual replacement of the indigenous Australo-Melanesians by Southern Mongoloids from Southern China. No skeletal remains in Southeast Asia dated to the Pleistocene epoch have been unearthed that would classified as being indisputably Mongoloid, although skeletal remains dated to this epoch have been found with Mongoloid traits. Skeletal remains in Southeast Asia dated to the Pleistocene epoch with Mongoloid traits indicate that Mongoloid admixture from areas north of Southeast Asia was already taking place at this time. This trend toward an increasingly Mongoloid skeletal character in Southeast Asia continued during the later Holocene epoch as an increasing number of the skeletal remains dated to the last 7,000 years are classified as having "Southern Mongoloid skeletal material" relative to the earlier epochs. The dental evidence that pre-historic Southeast Asian skeletal remains are of the sundadont dental type, and the dental evidence that Southeast Asians, including Negritos, are of the sundadont dental type supports the idea that it was sundadont Southern Mongoloids from Southern China whose gene flow was making Southeast Asia more Mongoloid instead of the sinodont Northeast Asian Mongoloids from farther north. Most of the Southern Mongoloids' gradual replacement of the indigenous Australo-Melanesians in Southeast Asia, a process done by "replacing Australo-Melanesian hunter-gatherers or assimilating populations of 'Proto-Malays'", was done "within the historical period". After the "gradual and complex replacement" of the indigenous Australo-Melanesians by Southern Mongoloids in Southeast Asia, the only remaining indigenous Australo-Melanesian population in Southeast Asia at the present time are the Negritos of Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and the Andaman Islands. The concept which is "[t]he important concept" here is that the gradual replacement of Australo-Melanesians by Southern Mongoloids in Southeast Asia was a gradual change in the cline between these two populations.[45]

Asiatic types in a book from 1914

Asiatic types in a book from 1914 Natives of North America in a book from 1914

Natives of North America in a book from 1914 Natives of South America in a book from 1914

Natives of South America in a book from 1914 Dayak man from Borneo, Dutch East Indies in 1900s

Dayak man from Borneo, Dutch East Indies in 1900s Young Māori woman with traditional tattoos from New Zealand (Aotearoa)

Young Māori woman with traditional tattoos from New Zealand (Aotearoa) Sea Sami man from the Sápmi region of Northern Norway^

Sea Sami man from the Sápmi region of Northern Norway^ Kalmyks, 19th century Salsky District, Russian Empire

Kalmyks, 19th century Salsky District, Russian Empire

Native Americans

In 1876, Oscar Peschel said that Native Americans were Mongoloids, and said that the Mongoloid features of Native Americans was evidence that Native Americans populated the Americas from Asia by way of the Bering Strait. Peschel said that some Native American tribes differ from Mongols in having a high nose bridge rather than a snub nose, but Peschel said that this different type of nose is not something shared by all Native Americans, so it cannot be considered a racial characteristic. Peschel said that Malays and Polynesians were Mongoloids due to their physical traits. Peschel said that the race of the Ainu people was not clear.[46]

In 1926, Aleš Hrdlička went on a journey that focused on "anthropological and archaeological matters" wherein Hrdlička traveled to the Bering Sea and places in Alaska. Hrdlička saw the conditions related to "the possibilities of the Mongoloid migrations through the Bering Sea", and Hrdlička concluded that these Mongoloid migrations were "so easy as to have been inevitable". Hrdlička concluded that Eskimos and American Indians come from a "common Mongoloid stem" which populated the Americas from the Alaska Peninsula.[47]

In 1998, Jack D. Forbes, professor of Native American Studies and Anthropology at the University of California, Davis, said that the racial type of the indigenous people of the Americas does not fall into the Mongoloid racial category.[48] Forbes said that due to the various physical traits indigenous Americans exhibit, some with "head shapes which seem hardly distinct from many Europeans", indigenous Americans must have either been formed from a mixture of Mongoloid and Caucasoid races or they descend from the ancestral, common type of both Mongoloid and Caucasoid races.[48] According to the National geographic, Native Americans also have partial West Eurasian origins. Nearly one-third of Native American genes come from an early West Eurasian people linked to the ancestors of Middle Easterners and Europeans, with the remaining two thirds deriving from early East Asian populations, rather than entirely from East Asians as previously thought, according to a newly sequenced genome. Based on the arm bone of a 24,000-year-old Siberian youth, the research could uncover new origins for America's indigenous peoples, as well as stir up fresh debate on Native American identities, experts say. Although these claims are controversial.[49]

Christos Stavrianos et al. (2012), of the Department of Endodology (Forensic Odontology) at Aristotle University, said that East Asians and Native Americans have been separated for at least 11,000 years on two distinct continents, yet due to East Asians and Native Americans sharing many physical traits in common due to common ancestry, some anthropologists classify them together as Mongoloids while other anthropologists, due to their differing traits, classify them as two separate races: the East Asian, and the Native American. Stavrianos said that the truth is that Mongoloids include various Asian groups, Eskimos, and Native Americans. Stavrianos said that Mongoloids are referred to as the "East Asian ethnic group" these days. Using the term "East Asian" to mean Mongoloids, Stavrianos said that the "East Asian" is a major racial group.[50]

Iran

Boris A. Malyarchuk et al. (2002) extracted the total DNA from a sample of 25 Persians from Khorasan Province, a population which Malyarchuk referred to as "Eastern Iranians." Out of the population of Eastern Iranians studied, Malyarchuk said that 20% had Mongoloid mtDNA groups. Out of the population of Eastern Iranians studied, Malyarchuk indicated that the distribution of Mongoloid mtDNA groups was: 4.0% M*, 4.0% D, 4.0% A, and 8.0% B. Unlike Eastern Iranians, Malyarchuk said that the "Western Iranians" completely lack a Mongoloid component in their DNA. Malyarchuk said that the difference between Western and Eastern Iranians does not conflict with the historical data, because it is known that only the central and eastern parts of Iran were part of the ethnic lands of Persians. Malyarchuk said that populations of an origin other than Persian lived in the western and southeastern parts of Iran since ancient times, such as Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Lurs, Balochi, etc. [51]

The Hazaras are an Iranian speaking ethnic group that live in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Genetically, the Hazara are a mixture of west Eurasian and eastern Eurasian components.[52]

While it has been found that "at least third to half of their chromosomes are of East Asian origin, PCA places them between East Asia and Caucasus/Middle East/Europe clusters".[53] Genetic research suggests that the Hazaras of Afghanistan cluster closely with the Uzbek population of the country, while both groups are at a notable distance from Afghanistan's Tajik and Pashtun populations.[53] There is evidence of both a patrimonial and maternal relation to Turkic Peoples and Mongols.[54]

East Asian male and female ancestry is supported by studies in genetic genealogy as well. East Asian maternal haplogroups (mtDNA) make up about 35%, which are virtually absent from bordering populations, suggesting that the male descendants of Turkic and Mongolian peoples, were accompanied by women of East Asian ancestry.[55] Women of Non-East Asian mtDNA in Hazaras are at about 65%, most which are West Eurasians and some South Asian.[56]

The most frequent paternal haplogroups found amongst the Pakistani Hazara were haplogroup C-M217 at 40%(10/25) and Haplogroup R1b at 32%[57] (8/25).

Hideo Matsumoto (2009) said that Iranians are "basically Caucasoid with a northern Mongoloid admixture." Matsumoto said that immunoglobulin G marker genes ab3st, characterizing the northern Mongoloid, and afb1b3, characterizing the southern Mongoloid, are specific to the Mongoloid. Matsumoto indicated that, in the Mazanderanian ethnic group in Iran, the gene frequency of ab3st is 8.5% and the gene frequency of afb1b3 is 2.6%. Matsumoto indicated that, in the Giranian ethnic group in Iran, the gene frequency of ab3st is 8.8% and the gene frequency of afb1b3 is 1.8%.[58]

Mestizos

Sherburne F. Cook (1946) said that Latin America has proceeded, nearly to completion, the combination of two distinct races to create a new type, the so-called mestizo. Cook said that the process started with a violent clash between a native, Mongoloid stock, and an invading Caucasian group.[60][61]

Katz and Suchey (1986) did a study that used males who were autopsied at the Department of Chief Medical Examiner-Coroner, County of Los Angeles. The study said that, based on physical appearance, it separated the Mexicans who had a Mongoloid appearance from those who had a Caucasoid physical appearance, with the Mongoloid groups constituting the "Mexican category." The study said that it paid attention to facial shape, hair form and color, skin color, and shovel-shaped incisors. The study said that its "Mexican category" was a category of individuals showing a heavy Mongoloid racial component in combination with Mexican ancestry.[62]

García‐Ramos et al. (2003) and Soto-Vega et al. (2004) both said that mestizos are "a complex mixture of European (Caucasian) and American native inhabitants (Mongoloid)."[63][64]

Ramírez-Cervantes et al. (2015) said that Mexican mestizos are "a complex mixture of European (Caucasian) and Native American (Mongoloid) genetics."[65]

South Asians

Hideo Matsumoto (2009) said that populations in the India and nearby regions are basically Caucasoid, with many of them having Mongoloid admixture, such as Hindus in India, Tamils in South India, Sinhalese in Sri Lanka, Brahmins in Assam, Nepalese in Nepal, and Kalitas in Assam. Matsumoto said that only some populations in the India and nearby regions are basically Mongoloid with Caucasoid admixture, such as Muslims in Bangladesh, and Ahom in Assam. Matsumoto said that immunoglobulin G marker genes ab3st, characterizing the northern Mongoloid, and afb1b3, characterizing the southern Mongoloid, are specific to the Mongoloid. For the following populations, Matsumoto indicated the following respective gene frequencies of ab3st and afb1b3: Hindus in India, 4.2% and 7.4%; Tamils in South India, 4.8% and 8.3%; Sinhalese in Sri Lanka, 2.6% and 12.5%; Brahmins in Assam, 8.6% and 12.7%; Nepalese in Nepal, 9.0% and 19.9%; Kalitas in Assam, 6.6% and 36.6%; Muslims in Bangladesh, 4.4% and 35.6%; and Ahom in Assam, 10.0% and 60.4%.[58]

Indian Austro-Asiatic speakers have East Asian paternal Haplogroup O-K18 related with Austro-Asiatic speakers of East Asia and Southeast Asia.[66]

British ethnographer, Herbert Hope Risley classified the people of the Ganges Delta up to Bihar as "Mongolo-Dravidian" or the "Bengali type".[67] This racial type included the Bengalis, Odias, Assamese and populations to the north in the Himalayas and was formed, according to Risley, through the intermixing of Mongolian and Dravidian populations.[67]

In his comparison between the upcountry Sinhalese and the Indian Tamil plantation workers of Sri Lanka, Howard S. Stoudt noted that the Sinhalese differed to the Indian Tamils because they were large chested with more Mongoloid faces.[27] American physical anthropologist, Carleton S. Coon claimed the partial Mongolian ancestry of the Sinhalese people had most likely originated in Assam.[68]

History of the concept

The earliest systematic use of the term was by Blumenbach in De generis humani varietate nativa (On the Natural Variety of Mankind, University of Göttingen, first published in 1775, re-issued with alteration of the title-page in 1776). Blumenbach included East and Southeast Asians, but not Native Americans or Malays, who were each assigned separate categories.

In 1865, biologist Thomas Huxley presented the views of polygenesists (Huxley was not one of them) as "some imagine their assumed species of mankind were created where we find them... the Mongolians from the Orangs".[69]

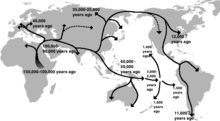

In 1964, archaeologist Kwang-chih Chang said that it seemed like the Mongoloid race originated in South China, and he said that it seemed like the Mongoloid race was differentiating itself from other races in the Late Pleistocene. Chang based these thoughts on a skull found in Sichuan and a skull found in Guangxi.[70]

In 1972, physical anthropologist Carleton S. Coon said, "From a hyborean [sic] group there evolved, in northern Asia, the ancestral strain of the entire specialized Mongoloid family".[71] In 1962, Coon believed that the Mongoloid "subspecies" existed "during most of the Pleistocene, from 500,000 to 10,000 years ago".[72] According to Coon, the Mongoloid race had not completed its "invasions and expansions" into Southeast Asia, the Americas, and the Pacific Islands until "[t]oward the end of the Pleistocene".[72] By this time, Coon hypothesized, the Mongoloid race had become "sapien".[72]

Mahinder Kumar Bhasin of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Delhi suggested in a review of an article referencing Mourant 1983 that "The Caucasoids and the Mongoloid almost certainly became differentiated from one another somewhere in Asia" and that "Another differentiation, which probably took place in Asia, is that of the Australoids, perhaps from a common type before the separation of the Mongoloids".[74]

Paleo-anthropologist Milford Wolpoff and Rachel Caspari characterize "his [Carleton Coon's] contention [as being] that the Mongoloid race crossed the 'sapiens threshold' first and thereby evolved the furthest".[75]

Douglas J. Futuyma, professor of evolutionary processes at the University of Michigan, said the Mongoloid race "diverged 41,000 years ago" from a Mongoloid and Caucasoid group which diverged from Negroids "110,000 years ago".[35]

In 1996, professor of anthropology, Akazawa Takeru of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto, said Mongoloids originated in Xinjiang during the "Ice Age".[44]

In 1999, Peter Brown of the Department of Anthropology and Paleoanthropology at the University of New England evaluated three sites with early East Asian modern human skeletal remains (Liujiang, Liuzhou, Guangxi, China; Shandingdong Man of (but not Peking Man) Zhoukoudian's Upper Cave; and Minatogawa in Okinawa) dated to between 10,175 and 33,200 years ago, and finds lack of support for the conventional designation of skeletons from this period as "Proto-Mongoloid". He stated that "The colonisation of the Americas by 11 kyr indicates an earlier date for the appearance of distinctively East Asian features, however, the earliest unequivocal evidence for anatomically East Asian people on the Asian mainland remains at 7000 years BP." He saw this as "possibility that migration across the Bering Strait went in two directions and the first morphological Mongoloids evolved in the Americas."[76]

A 2011 book about forensic anthropology stated, based on physical appearance, not accounting for admixture, there are considered to exist four basic ancestry groups into which someone can be placed: "the sub-Saharan African group ('Negroid'), the European group ('Caucasoid'), the Central Asian group ('Mongoloid'), and the Australasian group ('Australoid')."[77]

| James Laurie on Blumenbach's Five Classes, (1842) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: System of Universal Geography... (1842)[78] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Johann Blumenbach's Five Principal Varieties, (1865) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Caucasian variety. Colour white, cheeks rosy (s. 43); hair brown or chestnut-coloured (s. 52); head subglobular (s. 62); face oval, straight, its parts moderately defined, forehead smooth, nose narrow, slightly hooked, mouth small (s. 56). The primary teeth placed perpendicularly to each jaw (s. 62); the lips (especially the lower one) moderately open, the chin full and rounded (s. 56). In general, that kind of appearance which, according to our opinion of symmetry, we consider most handsome and becoming. To this first variety belong the inhabitants of Europe (except the Lapps and the remaining descendants of the Finns) and those of Eastern Asia, as far as the river Obi, the Caspian Sea and the Ganges; and lastly, those of Northern Africa. Mongolian variety. Colour yellow (s. 43); hair black, stiff, straight and scanty (s. 52); head almost square (s. 62); face broad, at the same time flat and depressed, the parts therefore less distinct, as it were running into one another; glabella flat, very broad; nose small, apish; cheeks usually globular, prominent outwardly; the opening of the eyelids narrow, linear; chin slightly prominent (s. 56). This variety comprehends the remaining inhabitants of Asia (except the Malays on the extremity of the trans-Gangetic peninsula) and the Finnish population of the cold part of Europe, the Lapps, &c. and the race of Esquimaux, so widely diffused over North America, from Behring's straights to the inhabited extremity of Greenland. Ethiopian variety. Colour black (s. 43); hair black and curly (s. 52); head narrow, compressed at the sides (s. 62); forehead knotty, uneven; malar bones protruding outwards; eyes very prominent; nose thick, mixed up as it were with the wide jaws (s. 56); alveolar edge narrow, elongated in front; the upper primaries obliquely prominent (s. 62); the lips (especially the upper) very puffy; chin retreating (s. 56). Many are bandy-legged (s. 69). To this variety belong all the Africans, except those of the north. American variety. Copper-coloured (s. 43); hair black, stiff, straight and scanty (s. 52); forehead short; eyes set very deep; nose somewhat apish, but prominent; the face invariably broad, with cheeks prominent, but not flat or depressed; its parts, if seen in profile, very distinct, and as it were deeply chiselled (s. 56); the shape of the forehead and head in many artificially distorted. This variety comprehends the inhabitants of America except the Esquimaux. Malay variety. Tawny-coloured (s. 43); hair black, soft, curly, thick and plentiful (s. 52); head moderately narrowed; forehead slightly swelling (s. 62); nose full, rather wide, as it were diffuse, end thick; mouth large (s. 56), upper jaw somewhat prominent with the parts of the face when seen in profile, sufficiently prominent and distinct from each other (s. 56). This last variety includes the islanders of the Pacific Ocean, together with the inhabitants of the Marianne, the Philippine, the Molucca and the Sunda Islands, and of the Malayan peninsula. | |||||||||

| Source: The Anthropological Treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1865)[79] | |||||||||

| John M. Ross on Huxley's Four Main Types, (1877) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: The Globe Encyclopedia of Universal Information Vol. II (1877)[80] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| William Henry Flower on Races, (1879) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It will be observed that the various regions of the world have been so grouped as to bring together those that are mainly inhabited:—(1) by the white or Caucasian races of Blumenbach, including the whole of Europe except the eastern frontiers of Russia, Africa north of the Sahara, and Asia south and west of the Himalayas; (2) by the yellow and red Mongolian and Mongoloid races, including the remainder of Asia, the Indo-Malay Archipelago, Eastern Polynesia, and the whole of America; (3) by the Australians, a race agreeing with the following section in every thing but the character of the hair; (4) by the frizzly-haired or black races—beginning with the Oceanic Negroes or Melanesians in the widest sense of the term (including the Tasmanians, Melanesians proper, Papuans, and Negritos of the Andaman Islands), and ending with the natives of Central and Southern Africa, the Negroes, Kaffirs, and Hottentots. | |||||||||

| Source: Catalogue of the Specimens... (1879)[81] | |||||||||

| George Bettany on Huxley's Four Main Types, (1892) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Australoid peoples have a chocolate-brown skin, dark brown or black eyes, black hair, usually wavy, narrow skull (long-headed), strongly-developed brow-ridges, projecting jaw, large teeth, thick lips, and broad nose. Besides the Australian natives, many of the hill-tribes of India, and perhaps the Egyptians, belong to this type. The Negroid peoples have all shades of brown and blackish-brown skin, brown or black eyes, black hair (short, crisp, or woolly), narrow skulls, little developed brow-ridges, projecting jaws, thick, projecting lips, and flat, broad nose. This type includes, besides the mass of Africans, the Cape Bushmen, who appear to be a specially modified branch, very short in stature, yellowish-brown in skin, with black eyes and hair; the Hottentots, whom Professor Huxley regards as a cross between Bushmen and ordinary negroes; the Negritos of the Andaman Islands, Malacca, and the Philippines; the Papuans, New Caledonians, and Tasmanians. The Mongoloid peoples include the greater part of the people of central, northern, and eastern Asia — a short and squat race, with yellowish-brown skin, black eyes and hair, the latter straight and coarse, short skulls (round-headed), with prominent brows, oblique eyes, and nose flat and small. The Chinese and Japanese differ from these in being long-headed, while the native Ainos of Japan are also distinguished by the hairy covering of their bodies. The Dyaks and Malays, the Polynesians, and the native Americans fall under the same classification, though with minor differences. Most of these peoples are long-headed, and in the Polynesians the straightness of the hair and obliquity of the eyes disappear. There remain the peoples known as whites, divided into Xanthrochroi, or fair-whites, and Melanochroi, or dark-whites. The fair-whites, tall, of almost uncoloured skin, belong to central and northern Europe; they have blue or grey eyes, light hair, ranging from straw-coloured to red and chestnut; their skulls vary from the longest forms to the shortest and roundest. The dark-whites are not sharply marked off from these, and include many Irishmen, Welshmen, and Bretons, together with Spaniards, Italians, Greeks, Arabs, Armenians, and Aryan Hindus. By intermixture of the latter with Australoids, a much darker mixture has been formed in India, making up the mass of the population. | |||||||||

| Source: The World's Inhabitants, or, Mankind, Animals, and Plants (3rd ed.) (1892)[82] | |||||||||

| Charles Morris on Flower's Three Extreme Types, (1892) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More recently Professor Flower has given an outline of a system of human classification which he regards as most in accordance with the present state of our knowledge on the subject.2 He considers that there are three extreme types, — those called by Blumenbach the Ethiopian, the Mongolian, and the Caucasian, around which all existing individuals of the human species can be ranged, but between which every possible intermediate form can be found. Of these the Ethiopian is secondarily divided into the African Negroes, the Hottentots and Bushmen, the Oceanic Negroes or Melanesians, and the Negritos as represented by the inhabitants of the Andaman and other Pacific islands. The Australians, whom Huxley takes as the type of a separate race, he considers to be a mixed people, as they combine the Negro type of face and skeleton, with hair of a different type. His second race is the Mongolian, represented in an exaggerated form by the Eskimo, in its typical condition by most of the natives of northern and eastern Asia, and in a modified type by the Malays. Excluding the Eskimo, the Americans form one group, whose closest affinity is with the Mongolian, yet which has so many special features that it might be viewed as a fourth primary division. His third or Caucasian race includes two sub-races, — the Xanthochroic and Melanochroic of Huxley. The seat of this race is Europe, northern Africa, and southwestern Asia, its linguistic division being into Aryans, Semites, and Hamites.

| |||||||||

| Source: The Aryan Race: Its Origins and Its Achievements (1892)[83] | |||||||||

| Charles Morris on Topinard's Three Species of Man, (1892) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topinard1 goes so far as to divide man into three distinct species. The first of these is the Mongolian, distinguished by a brachycephalic, or short skull, by low stature, yellowish skin, broad, flat countenance, oblique eyes, contracted eyelids, beardless face, hair scanty, coarse, and round in section. The second is the Caucasian, with moderately dolichocephalic, or long skull, tall stature, fair, narrow face, projecting on the median line, hair and beard abundant, light-colored, soft, and somewhat elliptical in section. His third species is the Negro, with skull strongly dolichocephalic, complexion black, hair flat and rolled into spirals, face very prognathous, and with several peculiarities of bodily structure not necessary to name here.

| |||||||||

| Source: The Aryan Race: Its Origins and Its Achievements (1892)[84] | |||||||||

Legal history

In 1858, the California State Legislature enacted the first bill of several that prohibited the attendance of "Negroes, Mongolians and Indians" from public schools.[85]

In 1885, the California State Legislature amended its code to make separate schools for "children of Mongoloid or Chinese descent."[85]

In 1911, the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization was using the term "Mongolic grand division," not only to include Mongols, but "in the widest sense of all," to include Malays, Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans. In 1911, the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization was placing all "East Indians," a term which included the peoples of "India, Farther India, and Malaysia," in the "Mongolic" grand division.[86]

In 1985, Michael P. Malone of the FBI Laboratory said that the FBI Laboratory is in a good position for the examination of Mongoloid hairs, because it does most of the examinations for Alaska, which has a large Mongoloid population, and it conducts examinations for the majority of Indian reservations in the United States.[87]

In 1987, a report to the National Institute of Justice indicated that the following skeletal collections were of the "Mongoloid" "Ethnic Group": Arctic Eskimo, Prehistoric North American Indian, Japanese, and Chinese.[88]

In 2005, an article in a journal by the FBI Laboratory defined the term "Mongoloid," as the term is used in forensic hair examinations. It defined the term as, "an anthropological term designating one of the major groups of human beings originating from Asia, excluding the Indian subcontinent and including Native American Indians."[89][90]

The United States Department of Justice has approved that, for forensic hair examination and/or laboratory reports, the hair examiner may state or imply that a human hair shows "Caucasian (European Ancestry), Negroid (African Ancestry) and/or Mongoloid (Asian or Native American Ancestry)" traits, which may or may not correspond to how an individual racially identifies.[91]

Features

The Mongoloid skull shows a round head shape with a medium-width nasal aperture, rounded orbital margins, massive cheekbones, weak or absent canine fossae, moderate prognathism, absent brow ridges, simple cranial sutures, prominent zygomatic bones, broad, flat, tented nasal root, short nasal spine, shovel-shaped upper incisor teeth (scooped out behind), straight nasal profile, moderately wide palate shape, arched sagittal contour, wide facial breadth and a flatter face.

— Caroline Wilkinson, Forensic Facial Reconstruction. (2004). page 86.[94]

Early craniological analyses focused on a few measurements of observations that were used to assign skulls to a racial type. This procedure has been recognized as too simplistic and impressionistic ... For example, an eastern Asian (or Mongoloid) skull, in general terms, can be described as round rather than long, with wide breadth, a high face and nose, frontal and lateral projection of the malars, broad palate, and a general facial flatness, especially in the upper face and interorbital region (Bowles 1977:343; Howells 1989:77; El-Najjar and McWilliams 1978:75; Krogman and İşcan 1986:271).[95]

William C. Boyd (1950) indicated that Mongoloids have the following skull characteristics: a short skull length, a broad skull breadth, a middle skull height, an arched sagittal contour, a very wide facial breadth, a high facial height, a rounded orbital opening, a narrow nasal opening, a sharp lower nasal margin, a straight facial profile, a moderately wide palate shape, and a general impression of the skull which is large, smooth, and rounded.[98]

Šefčáková and Thurzo (1994) said that the following are Mongoloid features: a rather wide and flat nose of little prominence, a generally flat face, shovel-shaped incisors, crown enamel extension, and macrodontia. The study said that the face flatness index is an important indicator of Mongoloid features.[99]

Jodi Blumenfield (2000) indicated that Mongoloids have the following craniofacial traits: a broad cranial form, a high, globular sagittal outline, a medium nose form, a small nasal bone size, a concave nasal profile, a medium nasal spine, a medium nasal sill, a shoveled incisor form, a moderate facial prognathism, a moderate alveolar prognathism, a projecting malar form, a parabolic/elliptic palatal form, a round orbital form, a robust mandible, a moderate chin projection, and a median chin form.[100]

Kim Ing-gon et al. (2001) said that, anatomically, Orientals are distinct from Caucasians. Kim said that the characteristics that distinguish Orientals are: a relatively prominent zygoma, a relatively prominent angle of the mandible, a relatively flat nose, a Mongoloid slant of the palpebral fissure, and a thick dermis.[101]

Robert B. Pickering et al. (2009) indicated that Mongoloids have the following racial characteristics of the skull: a long skull length, a broad skull breadth, a middle skull height, an arched sagittal contour, a very wide facial breadth, a high facial height, a rounded orbital opening, a narrow nasal opening, nasal bones that are wide and flat, a sharp lower nasal margin, a straight facial profile, a moderately wide palate that is a broad U-shape, 90%+ frequency of shovel-shaped incisors, and a large, smooth general form of the skull.[102]

Nitul Jain (2013) indicated that Asians and Native Americans have the following anthropological variations of the skeleton that are associated with racial characteristics of the skull: a broad skull width, an intermediate skull height, an intermediate profile of the skull in terms of prognathism, orbits that have circular openings, a rounded nasal opening, and an intermediate palate in terms of width.[103]

In "Whites" and in "Mongoloid populations", the shafts of the femurs curve toward the front of the person relative to how the femurs are in "Blacks".[104]

"Mongoloids" have femurs with more curvature and more twisting at the neck than the femurs of both "whites" and "blacks". Whites have femurs that are "intermediate in both curvature and twisting" between Mongoloids and blacks. Blacks have femurs with less curvature and less twisting at the head or neck than the femurs of both whites and Mongoloids.[105]

In 1962, Carleton S. Coon said that one of the reasons that Mongoloids have flatter faces than Caucasoids is due to the masseter and temporalis jaw muscles in the faces of Mongoloids being positioned more toward the front of the faces of Mongoloids relative to where these jaw muscles are positioned in the faces of Caucasoids.[106]

A 1992 study compared the features of North African skull samples dated to the Late Pleistocene against purported "mongoloid" and "australoid" features. The study found that the skull samples had at "moderate to high frequencies" the "Chinese features" of shovel-shaped incisors and a horizontally flat face, and the study found that the skull samples had at "moderate to high frequencies" the "southeast Asian traits" of a high degree of prognathism, strong brow ridges, projecting cheekbones and "malar tuberosities".[107]

According to George W. Gill physical traits of Mongoloid crania are generally distinct from those of the Caucasoid and Negroid races. He asserts that forensic anthropologists can identify a Mongoloid skull with an accuracy of up to 95%.[108] However, Alan H. Goodman cautions that this precision estimate is often based on methodologies using subsets of samples. He also argues that scientists have a professional and ethical duty to avoid such biological analyses since they could potentially have sociopolitical effects.[109]

Variation in craniofacial form between humans has been found to be largely due to differing patterns of biological inheritance. Modern cross-analysis of osteological variables and genome-wide SNPs has identified specific genes, which control this craniofacial development. Of these genes, DCHS2, RUNX2, GLI3, PAX1 and PAX3 were found to determine nasal morphology, whereas EDAR impacts chin protrusion.[110]

The East Polynesian, the Paleoindian/North American Archaic, and the Mongoloid/Late Amerindian are characterized by a "Square, heavy jaw". The East Polynesian and the Mongoloid/Late Amerindian are characterized by a "Median chin". The European is characterized by a "sharp, thin jaw" that has a "strong, prominent chin". Mongoloid peoples, meaning modern East Asians and Amerindians of the later time periods, are characterized by "robust" cheekbones that project forward and to either side of the face.[111]

The nasal sill bones of American Indians are of medium development and "sometimes even sharp", and, in this respect, they are like the nasal sill bones of "Whites" whose nasal sill bones are almost without exception sharp. The nasal bones of East Asians are "small" and "often flat". American Indians and East Asians almost never have a nasion depression which is the depression between the brow ridge and the bridge of the nose. The nasal sill bones of East Polynesians are "rounded", smooth and "dull" and, in this respect, they are like the nasal sill bones of sub-Saharan Africans and Australians/Melanesians. The nasal bones of East Polynesians are "large and prominent" and there is often a nasion depression in East Polynesians which is a trait that is also present in "Whites". East Polynesians have a lower nasal root than "Europeans". The nasal bridge of East Polynesians is not as straight in profile as the "European" nasal bridge, and the nasal bridge of East Polynesians does not have the "steeple shape" of the "Caucasoid" nasal bridge.[111]

Samoans are of the Mongoloid race but their features represent a "slightly different evolution since the time of their separation and isolation from their parental stock" or a retention of features that have been lost in other Mongoloid types. The "straight" or "low waves" hair of the Samoan is one such retention compared to the stiff, coarse hair that typifies the Mongoloid. Most of the characteristics of the Samoan have Mongoloid affinities such as: skin color, hair color, eye color, conjuctiva, amount of beard, hair on chest, nasal bridge, nostrils, lips, face width, biogonial width, cephalo-facial index, nasal height, ear height and chin. Polynesians lack characteristic Mongoloid shovel-shaped incisors, because this characteristic Mongoloid trait disappeared in the Polynesian population as the teeth of Polynesians reduced in size over the course of their evolutionary history.[112]

Mongoloid features are a mesocranic skull, fairly large and protruding cheekbones, nasal bones that are flat and broad, a nasal bridge that is slightly concave without depression in the nasion, "the lower borders of the piriform aperture are not sharp but guttered", shallow prenasal fossae, small anterior nasal spine, trace amounts of canine fossae and moderate alveolar prognathism.[113]

The Paleoindian has proto-Mongoloid morphology such as pronounced development of supraorbital ridges low frontals, marked post-orbital constriction, prominent and protruding occipitals, small mastoids, long crania and a relatively narrow bizygomatic breadth.[38]

The Mongoloid racial type is distinguished by forward-projecting malar (cheek) bones, comparatively flat faces, large circular orbits, "moderate nasal aperture with a slightly pointed lower margin", larger, more gracile braincase, broader skull, broader face and flatter roof of the nose.[114]

The traits of the Mongoloid skull are: long and broad skulls of intermediate height, arched sagittal contour, very wide facial contour, high face height, rounded orbital opening, narrow nasal opening, wide, flat nasal bones, sharp lower nasal margin, straight facial profile, moderate and white palate shape, 90%+ shovel-shaped incisors and large, smooth general form.[115]

Miquel Hernández of the Department of Animal Biology at the University of Barcelona said East Asians (Kyushu, Atayal, Philippines, Chinese, Hokkaido and Anyang) and Amerinds (Yaujos, Santa Cruz and Arikara) have the typical Mongoloid cranial pattern, but other Mongoloids such as Pacific groups (Easter Island, Mokapu, Guam and Moriori people), Arctic groups (Eskimos and Buriats), Fuegians (Selk’nam, Ya´mana, Kawe´skar) and the Ainu differ from this by having "larger cranial dimensions over many variables".[116]

The EDAR gene causes the Sinodont tooth pattern, and also affects hair texture,[117] jaw morphology,[118] and perhaps the nutritional profile of breast milk.[119]

Dennis C. Dirkmaat, professor of paleoanthropology and archaeology at Mercyhurst University,[120] said that Southeast Asian skulls can be distinguished from Asian and Native American skulls in that they are "smaller and less robust" with noses exhibiting a medium width without nasal overgrowth, and can "exhibit gracile features common to female skulls".[121]

Dr. Ann H. Ross, Co-Director of the Forensic Sciences Institute at North Carolina State University,[122] in a presentation on the concept of "race" (written in scare quotes) from the perspective of forensic anthropology, said individuals of "Asian ancestry" have an "intermediate profile", meaning the part of the maxilla is "moderate" compared to individuals of "African ancestry" who have a "projecting maxilla", and compared to individuals who are "White/Hispanic" who generally have a "straight profile" or "lack of prognathism". She qualified her statement about Hispanics by adding that their lack of prognathism would not hold true for Hispanic populations with "African admixture".[123]

Qing He et al. of the Obesity Research Center at Columbia University did a study on "fat distribution" of 358 prepubertal children and the study said that Asians have less gynoid fat than African Americans and more relative trunk fat than Caucasians, but less relative extremity fat than Caucasians.[124]

Cheekbones

Pranitan Rattanasalee et al. (2014) said that the cheekbones of Mongoloid skulls are notably higher than the cheekbones of Caucasoid and Negroid skulls.[125]

Mandible

William S. Laughlin (1963) said, "The enormously broad ascending ramus is characteristic of many Mongoloid groups. The breadth of this feature in Eskimos and Aleuts exceeds the breadth in Neanderthal man."[126]

A study took panoramic radiographs of two sites at the angle of the mandible of 79 dental students, consisting of 20 male Caucasoids, 20 female Caucasoids, 17 male Mongoloids and 22 female Mongoloids. The abstract for the study said that the Mongoloids in the study had about "20% higher bone density at the angle of the mandible" than the Caucasoids in the study with a p-value of 0.0094 for the males and a p-value of 0.0004 for females.[127]

Eyes

In 1919, John Cameron wrote that vertical distances of the openings of the eye sockets of Mongoloids are the longest, the vertical distances of the openings of the eye sockets of Europeans are intermediate, and the vertical distances of the openings of the eye sockets of aboriginal Australians and Melanesians are the shortest.[128]

Jeong Sang-ki et al. of Chonnam University, using both Asian and Caucasian cadavers as well as four healthy young Korean men, said that "Asian eyelids" whether "Asian single eyelids" or "Asian double eyelids" had more fat in them than in Caucasians.[129] Jeong et al. said that the cause of the "Asian single eyelid" was that "the orbital septum fuses to the levator aponeurosis at variable distances below the superior tarsal border; (2) preaponeurotic fat pad protusion and a thick subcutaneous fat layer prevent levator fibers from extending toward the skin near the superior tarsal border; and (3) the primary insertion of the levator aponeurosis into the orbicularis muscle and into the upper eyelid skin occurs closer to the eyelid margin in Asians."[129]

The Mongoloid eyelid is characterized by puffiness of the upper eyelid, "superficial expansion of the levator aponeurosis" that are "turned up around this transverse ligament to become the orbital septum", "low position of the preaponeurotic fat" and narrowness of the palpebral fissure.[130]

Skin

Mongoloid skin has thick skin cuticle and an abundance of carotene (yellow pigment).[44]

Willett Enos Rotzell, professor of Botany and Zoology at the Hahnemann Medical College, said the Asian race has skin color ranging from a yellowish tint to an olive shade, with black and coarse hair with a circular cross section, an absent or scanty beard, a brachycephalic skull, prominent cheek bones and a broad face. Rotzell said that the Asian race has its original home in Asia.[131]

William F. Loomis (1967) said that Mongoloids have yellowish skin, because the stratum corneum of Mongoloids is packed with disks of keratin, allowing Mongoloids to live within 20 degrees of the equator, even though the skin of Mongoloids only has small amounts of melanin. Loomis said that, even on the equator, peoples of Mongoloid derivation acquire pigmentation, e.g. the Mongoloids who entered the Americas by way of the Bering Straits at latitude 66°N as recently as 20,000 to 10,000 years ago, who were previously of medium-light skin. Loomis said that, in the Mongoloids of Asia and the Americas, constitutive keratinization is a defense against the production of too much vitamin D.[132]

The average size of random melanosomes of "Asian skin" for Chinese individuals of Fitzpatrick phototype IV through V was measured to be 1.36 ± 0.15 μ m 2 × 10−2 which was between the higher value of 1.44 ± 0.67 μm2 × 10−2 measured for "African/American skin" of Fitzpatrick phototype VI and the lower value of 0.94 ± 0.48 μm2 × 10−2 measured for "Caucasian skin" of Fitzpatrick phototype II. The ratio of clustered to distributed melanosomes was 37.4% clustered vs. 62.6% distributed in Asian skin, 84.5%. clustered vs. 15.5% distributed in Caucasian skin and 11.1% clustered vs. 88.9% distributed in African/American skin.[133]

Both darker-skinned and lighter-skinned Asians have a thicker dermis than Caucasians of comparable skin pigment which may be the reason for a "substantially lower incidence of fine wrinkles" in Asians when compared to Caucasians, and this lower incidence of fine wrinkles may be the reason for the "myth" that Asian faces age slower than Caucasian faces.[134]

Asian people and black people have a thicker dermis than white people. The skin of Asian people and black people also has more sun protection than the skin of white people due to Asian people and black people having larger and more numerous melanosomes in their skin than white people. The thicker dermis and the more numerous melanosomes of larger size might be the reasons that Asian people and black people have a lower incidence of facial wrinkles than white people.[135]

Peter Bellwood (2007) said that the skin of Mongoloids has "a thick stratum corneum packed with keratin but little pigmentation."[41]

The skin of Asians turns darker and yellower with age relative to the skin of Caucasians.[136]

Teeth

In 1953, Dentist Stephen Kolas wrote that Palatine tori and mandibular tori are more commonly present in Mongoloids than in Caucasians and Negroids.[137]

Kim S. Kimminau (1993) said that, as compared to Native Americans, there is a general trend of relatively large anterior teeth as compared to posterior teeth among Asian Mongoloids. Kimminau said that it is not typical for Mongoloids to have elaborated occlusional surfaces.[138]

Mongoloids generally have large incisors, large canines, large molars and small premolars.[139]

In 1996, Rebecca Haydenblit of the Hominid Evolutionary Biology Research Group at Cambridge University did a study on the dentition of four pre-Columbian Mesoamerican populations and compared their data to other Mongoloid populations.[140] She said that Tlatilco, Cuicuilco, Monte Albán and Cholula populations followed an overall Sundadont dental pattern characteristic of Southeast Asia rather than a Sinodont dental pattern characteristic of Northeast Asia.[140]

George Richard Scott, physical anthropologist at the University of Nevada, said that some East Asians (in particular, Koreans, some Han Chinese and some Japanese), as well as Native Americans, have a distinctive dental pattern known as Sinodonty, where, among other features, the upper first two incisors are not aligned with the other teeth, but are rotated a few degrees inward and are shovel-shaped.[141]

A "mandibular torus" is a trait that commonly occurs in "Mongoloid populations".[142]

Mongoloid teeth are larger than Caucasoid and Negroid teeth. Mongoloids have mandibles that are "robust", and Mongoloids have mandibles that are "similar" to the mandibles of Negroids in respect to the chins of Mongoloids and Negroids not being as prominent as the chins of Caucasoids and in respect to the chins of Mongoloids and Negroids being "median" while the Caucasoid chin is "bilateral".[143]

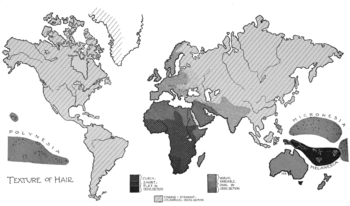

Hair

Commenting on the lack of body hair (glabrousness) of Negroids and Mongoloids, Carleton S. Coon wrote in 1939 that "[b]oth negroid and mongoloid skin conditions are inimical to excessive hair development except upon the scalp."[144]

Edward J. Imwinkelried (1982), Professor of Law at Washington University, said that Mongoloid hair has a dense pigment, which is distributed rather evenly. Imwinkelried said that the shaft of Mongoloid hair has a circular or triangular shape when viewing its cross section. Imwinkelried said that there is a tendency of Mongoloid hair to be coarse and straight.[145]

Mongoloid males have "little or no facial or body hair".[146] Mongoloid hair is coarse, straight, blue-black and weighs the most out of the races.[147] The size of the average Mongoloid hair is 0.0051 square millimetres (7.9×10−6 sq in) based on samples from Chinese, North and South American Indians, Eskimos and Thais.[148] Mongoloid hair whether it be Sioux, Ifugao or Japanese has the thickest diameter out of all human hair.[149]

Douglas W. Deedrick, Unit Chief of the Trace Evidence Unit for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, said that hairs of "Mongoloid or Asian origin" are characterized as being straight and coarse with a circular cross section and a wider diameter than those of other "racial groups". He said that the cuticle is thicker than those of Negroid or Caucasian hairs while the medulla is "continuous and wide". He said that the pigment granules are smaller than the larger pigment granules of Negroid hair, and the pigment granules in the cortex are "generally larger" than those of Caucasian hair. Unlike the "evenly distributed" pigment granules of Caucasian hair, Asian hair frequently has clusters of pigment granules that form "patchy areas".[150]

The theoretical index of hair bending stiffness is calculated using the thickest and thinnest axial diameters of human hair, and this index differs by race. The hair stiffness indexes of Mongoloids, Africans and Europeans are: 4.23, 2.75 and 1.59, respectively. This means that Mongoloids with the highest hair stiffness index value of 4.23 have the most rigid hair and Europeans with the lowest hair stiffness index value of 1.59 have the least rigid hair. The eccentricity of hair cross-sectional shape index is also calculated using the thickest and thinnest axial diameters of human hair, and this index also differs by race. The hair eccentricity indexes of Africans, Europeans and Mongoloids are: 1.74, 1.49 and 1.30, respectively. This means that Africans with the highest hair eccentricity index value of 1.74 have the curliest hair and Mongoloids with the lowest hair eccentricity index value of 1.30 have the least curly hair.[151]

Proto-Mongoloids

Arteaga et al. (1951) said that the immunological traits of the Mexican Indians are not in disagreement with the historical and anthropological basis for their Mongoloid origin. Arteaga said that the Otomi and the Tarascans are considered to be typical Mongoloids. Arteaga said that the Mexican Indians and the Chinese are both typical Mongoloids, but the Mexican Indians and the Chinese differ somewhat, with the Mexican Indians having a preponderance of O and M blood phenotypes, while the Chinese have high frequencies of A and B blood phenotypes, and low frequencies of M and E blood phenotypes. Arteaga accounted for this blood phenotype frequency difference by accepting the fact that the American Indian may represent the Proto-Mongoloid, while the Chinese are a rather mixed group.[153]

Harold E. Driver (1969), a leading figure in postwar American anthropology, said that American Indians physically resemble Asians more than any other major Old World physical type. Driver said that the resemblance, however, is closer to the marginal Mongoloids of Indonesia, West Central Asia, and Tibet than to the central Mongoloids of Mongolia, China, or Japan. Driver said that the marginal Mongoloids represent an earlier and less specialized racial type in comparison to the central Mongoloids. Driver said that American Indians came from the ancestors of the marginal Mongoloids, who were present in most of Asia, north and east of India. Driver said that, in comparison to the central Mongoloids, the marginal Mongoloids share more physical traits in common with Europeans. Driver said that the greater physical resemblance of marginal Mongoloids to Europeans is a fact that is explained by the hypothesis that the separation of Mongoloids and Europeans had not progressed very far when Mongoloids in Northeast Asia started to migrate into Alaska by way of the land bridge across the Bering Strait.[154][155]

Tsunehiko Hanihara of the Department of Anatomy at Jichi Medical School suggests that the inhabitants of Aogashima and Okinawa, Minatogawa Man, the Jōmon and the modern Ainu are most likely directly descended from Proto-Mongoloids of Late Pleistocene Sundaland.[156]

Mark J. Hudson, Professor of Anthropology at Nishikyushu University, said Japan was settled by a Proto-Mongoloid population in the Pleistocene who became the Jōmon and their features can be seen in the Ainu, Okinawan and as well in Yamato people. Hudson said that, later, during the Yayoi period, the Neo-Mongoloid type entered Japan. Hudson said that genetically Japanese people are primarily Neo-Mongoloid with Proto-Mongoloid admixture.[157]

Theodore G. Schurr of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania said that Mongoloid traits emerged from Transbaikalia, central and eastern regions of Mongolia, and several regions of Northern China. Schurr said that studies of cranio-facial variation in Mongolia suggest that the region of modern-day Mongolians is the origin of the Mongoloid racial type".[114]

In 1959, Dr. Wu Rukang of the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Academia Sinica, China, said the remains of Liukiang human fossils were an early type of evolving Mongoloid that indicated South China was the birthplace where the Mongoloid race originated.[113]

Dr. Marta Mirazón Lahr of the Department of Biological Anthropology at Cambridge University said there are two hypotheses on the origin of Mongoloids. Lahr said that one hypothesis is that Mongoloids originated in north Asia due to the regional continuity in this region and this population conforming best to the standard Mongoloid features. Lahr said that the other hypothesis is that Mongoloids originate from Southeast Asian populations that expanded from Africa to Southeast Asia during the first half of the Upper Pleistocene and then traveled to Australia-Melanesia and East Asia. Lahr said that the morphology of the Paleoindian is consistent with the proto-Mongoloid definition.[38]

Hisao Baba and Shuichiro Narasaki of the Department of Anthropology at the National Science Museum, in Tokyo, Japan, said that it is broadly accepted that Zhoukoudian Upper Cave Man and maybe Liujian Man were "so-called proto-Mongoloids" who did not have a completely developed Mongoloid complex.[158]

Neoteny

In 1951, Ashley Montagu claimed "the skeleton of the classic Mongoloid type is very delicately made, even down to the character of the sutures of the skull which, like those of the infant skull, are relatively smooth and untortuous. In fact the Mongoloid presents so many physical traits which are associated with the late fetus or young infant that he has been called a fetalized, infantilized or pedomorphic type. Those who have carefully observed young babies may recall that the root of the nose is frequently flat or low as in Mongoloids, and that an internal epicanthic fold in such instances is usually present. The smaller number of individual head hairs and the marked hairlessness of the remainder of the body are infantile traits, as are likewise the small mastoid processes, the shallow fossa into which the jawbone fits (the mandibular fossa), the rather stocky build, the large brain-pan and brain, lack of brow ridges, and quite a number of other characters."[7]

Stephen Oppenheimer of the Institute of Cognitive & Evolutionary Anthropology at Oxford University said, "An interesting hypothesis put forward by paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould many years ago was that the package of the Mongoloid anatomical changes could be explained by the phenomenon of neoteny, whereby an infantile or childlike body form is preserved in adult life. Neoteny in hominids is still one of the simplest explanations of how we developed a disproportionately large brain so rapidly over the past few million years. The relatively large brain and the forward rotation of the skull on the spinal column, and body hair loss, both characteristic of humans, are found in foetal chimps. Gould suggested a mild intensification of neoteny in Mongoloids, in whom it has been given the name pedomorphy. Such a mechanism is likely to involve only a few controller genes and could therefore happen over a relatively short evolutionary period. It would also explain how the counterintuitive retrousse [turned up at the end] nose and relative loss of facial hair got into the package". "[D]ecrease unnecessary muscle bulk, less tooth mass, thinner bones and smaller physical size; ...this follows the selective adaptive model of Mongoloid evolution".[159]

Paul Storm of the Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Netherlands, said that in Australasia there are two types of cranial morphologies—the "Sunda" (Mongoloid) and "Sahul" (Australoid) types. Storm said that the "Sunda" (Mongoloid) type includes Chinese and Javanese people, and he said that the "Sahul" (Australoid) type includes Papuans and Australian aborigines. Storm said that the "Sunda" (Mongoloid) type has a flat face with high cheek bones, and Storm said that this "flat face" of the Chinese and Javanese is known as the "mongoloid face". Storm further said that the "Sunda" (Mongoloid) type has a more rounded skull, "feminine (juvenile) characters", a "retention of juvenile characters" and a limited outgrowth of superstructures such as the supraorbital region. Storm said that "Sunda" (Mongoloid) skulls resemble female skulls more than "Sahul" (Australoid) skulls resemble female skulls. Storm said that the skulls of "Asian" males ("Chinese and Javanese") have "more feminine characteristics", and he said that they have "many feminine characters in contrast with Australians".[160]

Paul Storm said that Asia contained humans with "generalized" cranial morphology, but between 20,000 BP and 12,000 BP this generalized type disappeared as a new type emerged. This new type had a flatter face with more pronounced cheekbones, a more rounded head, reduced sexual dimorphism (male skulls started to resemble female skulls), a reduction of superstructures such as the supraorbital region and an increased "retention of juvenile characters". Storm said that this new type of skull that emerged is called the "Proto-Sunda" (Proto-Mongoloid) type, and it is distinguished from the "Sunda" (Mongoloid) type by being more "robust". Storm said that the "Mongoloid" or "Asian" type of skull developed relatively fast during a population bottleneck in Asia that happened during the Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene through a microevolutionary trend that involved a "continuation of neoteny and gracilisation trends". Due to different courses of evolution, Storm said that these two types of skulls, the "Sunda" (Mongoloid) type and the "Sahul" (Australoid) type, are now clearly recognizable at the present time.[160]

Andrew Arthur Abbie who was an anatomist and anthropologist at the University of Adelaide[161] talked about leg-to-torso length being related to neoteny. Abbie said that women normally have shorter legs than men, and he said that shorter legs are the normal condition in some ethnic groups such as Mongoloids. Abbie said that Mongoloids of whom he listed the people of "China, Japan and the Americas" have proportionately larger heads and shorter legs than Europeans, and he said that this is a case of "paedomorphism". Abbie said that aboriginal Australians and some African ethnic groups such as the "Negro", the "Hottentot" and the "Nubian" peoples have proportionately longer legs than Europeans, and he said that this is a case of "gerontomorphism". Abbie said that ethnic groups with proportionately shorter legs than Europeans are relatively "paedomorphic" in terms of leg-to-torso ratios when compared to Europeans, and he said that ethnic groups with proportionately longer legs than Europeans are relatively "gerontomorphic" in terms of leg-to-torso ratios when compared to Europeans.[162]

Cold adaptation

Most mongoloids tend to have short necks, small hands and feet, and short distal portions in their arms and legs. The typical mongoloid face has been described as a model of climatic engineering. The brow ridges with their cold-vulnerable sinuses are reduced; the malars are extended forward and enlarged hence the external nose protrusion is reduced; the eye is protected by fatty lids whose borders are brought closer together, which in turn helps reduce the glare of light. The distended malars and maxillary sinuses are also protected by fatty pads, which helps to give the typical mongoloid face its flat appearance. In addition Mongoloids have sparse beards, which may be an advantage because exhaled breath, in cold regions at any rate, can freeze the beard and underlying skin.

— Rupert I. Murrill, Some Aspects of Human Racial Adaptation. (1960). Page 205.[163]

Akazawa Takeru, an anthropology professor at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto, wrote that Mongoloid features are an adaptation to the cold of the Mammoth steppe.[44] He mentions the Lewis waves of warm blood cyclical vasodilation and vasoconstriction of the peripheral capillaries in Mongoloids as an adaption to the cold.[44] He lists the short limbs, short noses, flat faces, epicanthic fold and lower surface-to-mass ratio as further Mongoloid adaptations to cold.[44] Mongoloids evolved hairlessness to keep clean while wearing heavy garments for months without bathing during the Ice Age.[44]

Nicholas Wade said that biologists have speculated that the Mongoloid skull type was the result of natural selection in response to a cold climate, and Wade said that the Mongoloid skull type first started to indisputably appear in the archaeological record 10,000 years ago. Wade said that biologists have speculated that the fat in the eyelids of Mongoloids and the stocky builds of Mongoloids were selected for as adaptations to the cold.[164]

Takasaki Yuji of Akita University said that, "Mongoloid ancestors had evolved over time in cold environments" and the short limbs of the Mongoloid was due to Allen's ecological rule.[165]

Writing in 1980, anthropology professor Joseph K. So at Trent University in Ontario cited a 1965 study by J. T. Steegman showing that the so-called cold-adapted Mongoloid face provided no greater protection against frostbite than the facial structure of European subjects.[166] In explaining Mongoloid cold-adaptiveness, So cites the work of W. L. Hylander (1977) where Hylander said that in the Eskimo (Inuit), for example, the reduction of the brow ridge and flatness of the face are instead due to internal structural configurations that are cold-adapted in the sense that they produce a large vertical bite force necessary to chew frozen seal meat.[166]

.jpg)

Miquel Hernández of the Department of Animal Biology at the University of Barcelona said that the high and narrow nose of Eskimos (Inuit) and the Neanderthals is an adaptation to a cold and dry environment, since it contributes to warming and moisturizing the air and the "recovery of heat and moisture from expired air".[116]

A. T. Steegman of the Department of Anthropology at State University of New York investigated the assumption that Allen's rule caused the structural configuration of the Arctic Mongoloid face.[167] Steegman did an experiment that involved the survival of rats in the cold.[167] Steegman said that the rats with narrow nasal passages, broader faces, shorter tails and shorter legs survived the best in the cold.[167] Steegman paralleled his findings with the Arctic Mongoloids, particularly the Eskimo and Aleut, by claiming these Arctic Mongoloids have similar features in accordance with Allen's rule: a narrow nasal passage, relatively large heads, long to round heads, large jaws, relatively large bodies, and short limbs.[167]

Kenneth L. Beals of the Department of Anthropology at Oregon State University said that the indigenous people of the Americas have cephalic indexes that are an exception to Allen's rule, since the indigenous people of the hot climates of North and South America have cold-adapted, high cephalic indexes.[168] Beals said that these peoples have not yet evolved the appropriate cephalic index for their climate, being, comparatively, only recently descended from the cold-adapted Arctic Mongoloid.[168]

In 1950, Carleton S. Coon et al. said that Mongoloids have faces that are adapted to the extreme cold of subarctic and arctic conditions. Coon et al. said that Mongoloids have eye sockets that have been extended vertically to make room for the adipose tissue that Mongoloids have around their eyeballs. Coon et al. said that Mongoloids have "reduced" brow ridges to decrease the size of the air spaces inside of their brow ridges known as the frontal sinuses which are "vulnerable" to the cold. Coon et al. said that Mongoloid facial features reduce the surface area of the nose by having nasal bones that are flat against the face and having enlarged cheekbones that project forward which effectively reduce the external projection of the nose.[106]

Carleton S. Coon also has a hypothesis for why noses on Mongoloids are very distinct. Typically, the nose is not very prominent on the face of a Mongoloid. Their frontal sinus is also reduced in order to allow more room for padding to protect from their cold environment. Regardless of the environment that the Mongoloid is in, their nose helps reduce the stress of the environment on their body by moistening the air inspired to cool the body off instead of doing a straight up heat exchange.[169]

The Asian mt-DNA Haplogroup D has been shown in a small Japanese study[170] to provide greater heat production upon exposure to cold than other haplogroups prevalent in the area.

Mongolian spot

A Mongolian spot, also known as Mongolian blue spot, congenital dermal melanocytosis,[171] and dermal melanocytosis[171] is a benign, flat, congenital birthmark with wavy borders and irregular shape. In 1883 it was described and named after Mongolians by Erwin Bälz, a German anthropologist based in Japan.[172][173][174][175] It normally disappears three to five years after birth and almost always by puberty.[5] The most common color is blue, although they can be blue-gray, blue-black or deep brown.

The spot is prevalent among East, South, Southeast, North and Central Asian peoples, Indigenous Oceanians (chiefly Micronesians and Polynesians), Sub-Saharan Africans,[176] Amerindians,[177] non-European Latin Americans, Caribbeans of mixed-race descent, and Turkish people.[178][179][180][181] They occur in about 90 to 95% of Asian and 80 to 85% Native American infants.[180] Approximately 90% of Polynesians and Micronesians are born with Mongolian spots, as are about 46% of children in Latin America,[182] where they are associated with non-European descent. These spots also appear on 5–10% of babies of full Caucasian descent; Coria del Río in Spain has a high incidence due to the presence of descendants of Hasekura Tsunenaga, the first Japanese official envoy to Spain in the early 17th century.[180][183] Black babies have Mongolian spots at a frequency of 96%.[184]

Genetic research

Genetic research into the separation time between the major racial groups was presented as early as 1985 by Masatoshi Nei. Nei (1985) found a separation time between Negroid and Eurasian (Caucasoid and Mongoloid taken together) of roughly 110,000 years, and a separation time between the Caucasoid and Mongoloid groups of roughly 40,000 years.[188]

In 2006, Yali Xue et al. of the genome research Sanger Institute conducted a study of linkage disequilibrium that said that northern populations in East Asia started to expand in number between 34 and 22 thousand years ago, before the last glacial maximum at 21–18 KYA, while southern populations started to expand between 18 and 12 KYA, but then grew faster, and suggests that the northern populations expanded earlier because they could exploit the abundant megafauna of the "Mammoth Steppe", while the southern populations could increase in number only when a warmer and more stable climate led to more plentiful plant resources such as tubers.[189]