Molecular symmetry

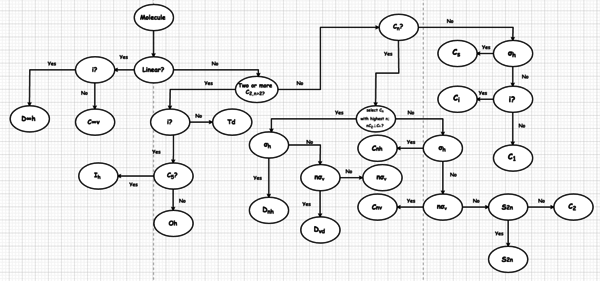

Molecular symmetry in chemistry describes the symmetry present in molecules and the classification of molecules according to their symmetry. Molecular symmetry is a fundamental concept in chemistry, as it can be used to predict or explain many of a molecule's chemical properties, such as its dipole moment and its allowed spectroscopic transitions. Many university level textbooks on physical chemistry, quantum chemistry, and inorganic chemistry devote a chapter to symmetry.[1][2][3][4][5]

The predominant framework for the study of molecular symmetry is group theory. Symmetry is useful in the study of molecular orbitals, with applications such as the Hückel method, ligand field theory, and the Woodward-Hoffmann rules. Another framework on a larger scale is the use of crystal systems to describe crystallographic symmetry in bulk materials.

Many techniques for the practical assessment of molecular symmetry exist, including X-ray crystallography and various forms of spectroscopy. Spectroscopic notation is based on symmetry considerations.

Symmetry concepts

The study of symmetry in molecules makes use of group theory.

| Rotational axis (Cn) | Improper rotational elements (Sn) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chiral no Sn | Achiral mirror plane S1 = σ | Achiral inversion centre S2 = i | |

| C1 |  |  |  |

| C2 |  |  |  |

Elements

The point group symmetry of a molecule can be described by 5 types of symmetry element.

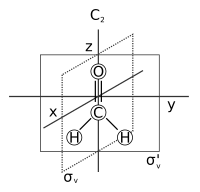

- Symmetry axis: an axis around which a rotation by results in a molecule indistinguishable from the original. This is also called an n-fold rotational axis and abbreviated Cn. Examples are the C2 axis in water and the C3 axis in ammonia. A molecule can have more than one symmetry axis; the one with the highest n is called the principal axis, and by convention is aligned with the z-axis in a Cartesian coordinate system.

- Plane of symmetry: a plane of reflection through which an identical copy of the original molecule is generated. This is also called a mirror plane and abbreviated σ (sigma = Greek "s", from the German 'Spiegel' meaning mirror).[6] Water has two of them: one in the plane of the molecule itself and one perpendicular to it. A symmetry plane parallel with the principal axis is dubbed vertical (σv) and one perpendicular to it horizontal (σh). A third type of symmetry plane exists: If a vertical symmetry plane additionally bisects the angle between two 2-fold rotation axes perpendicular to the principal axis, the plane is dubbed dihedral (σd). A symmetry plane can also be identified by its Cartesian orientation, e.g., (xz) or (yz).

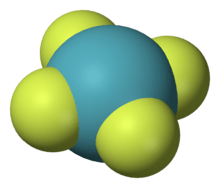

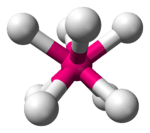

- Center of symmetry or inversion center, abbreviated i. A molecule has a center of symmetry when, for any atom in the molecule, an identical atom exists diametrically opposite this center an equal distance from it. In other words, a molecule has a center of symmetry when the points (x,y,z) and (−x,−y,−z) correspond to identical objects. For example, if there is an oxygen atom in some point (x,y,z), then there is an oxygen atom in the point (−x,−y,−z). There may or may not be an atom at the inversion center itself. Examples are xenon tetrafluoride where the inversion center is at the Xe atom, and benzene (C6H6) where the inversion center is at the center of the ring.

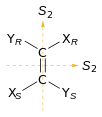

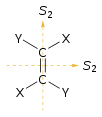

- Rotation-reflection axis: an axis around which a rotation by , followed by a reflection in a plane perpendicular to it, leaves the molecule unchanged. Also called an n-fold improper rotation axis, it is abbreviated Sn. Examples are present in tetrahedral silicon tetrafluoride, with three S4 axes, and the staggered conformation of ethane with one S6 axis. An S1 axis corresponds to a mirror plane σ and an S2 axis is an inversion center i. A molecule which has no Sn axis for any value of n is a chiral molecule.

- Identity, abbreviated to E, from the German 'Einheit' meaning unity.[7] This symmetry element simply consists of no change: every molecule has this element. While this element seems physically trivial, it must be included in the list of symmetry elements so that they form a mathematical group, whose definition requires inclusion of the identity element. It is so called because it is analogous to multiplying by one (unity). In other words, E is a property that any object needs to have regardless of its symmetry properties.[8]

Operations

The five symmetry elements have associated with them five types of symmetry operation, which leave the molecule in a state indistinguishable from the starting state. They are sometimes distinguished from symmetry elements by a caret or circumflex. Thus, Ĉn is the rotation of a molecule around an axis and Ê is the identity operation. A symmetry element can have more than one symmetry operation associated with it. For example, the C4 axis of the square xenon tetrafluoride (XeF4) molecule is associated with two Ĉ4 rotations (90°) in opposite directions and a Ĉ2 rotation (180°). Since Ĉ1 is equivalent to Ê, Ŝ1 to σ and Ŝ2 to î, all symmetry operations can be classified as either proper or improper rotations.

Symmetry groups

Groups

The symmetry operations of a molecule (or other object) form a group. In mathematics, a group is a set with a binary operation that satisfies the four properties listed below.

In a symmetry group, the group elements are the symmetry operations (not the symmetry elements), and the binary combination consists of applying first one symmetry operation and then the other. An example is the sequence of a C4 rotation about the z-axis and a reflection in the xy-plane, denoted σ(xy)C4. By convention the order of operations is from right to left.

A symmetry group obeys the defining properties of any group.

(1) closure property:

For every pair of elements x and y in G, the product x*y is also in G.

( in symbols, for every two elements x, y∈G, x*y is also in G ).

This means that the group is closed so that combining two elements produces no new elements. Symmetry operations have this property because a sequence of two operations will produce a third state indistinguishable from the second and therefore from the first, so that the net effect on the molecule is still a symmetry operation.

(2) associative property:

For every x and y and z in G, both (x*y)*z and x*(y*z) result with the same element in G.

( in symbols, (x*y)*z = x*(y*z ) for every x, y, and z ∈ G)

(3) existence of identity property:

There must be an element ( say e ) in G such that product any element of G with e make no change to the element.

( in symbols, x*e=e*x= x for every x∈ G )

(4) existence of inverse property:

For each element ( x ) in G, there must be an element y in G such that product of x and y is the identity element e.

( in symbols, for each x∈G there is a y ∈ G such that x*y=y*x= e for every x∈G )

The order of a group is the number of elements in the group. For groups of small orders, the group properties can be easily verified by considering its composition table, a table whose rows and columns correspond to elements of the group and whose entries correspond to their products.

Point groups and permutation-inversion groups

The successive application (or composition) of one or more symmetry operations of a molecule has an effect equivalent to that of some single symmetry operation of the molecule. For example, a C2 rotation followed by a σv reflection is seen to be a σv' symmetry operation: σv*C2 = σv'. ("Operation A followed by B to form C" is written BA = C).[8] Moreover, the set of all symmetry operations (including this composition operation) obeys all the properties of a group, given above. So (S,*) is a group, where S is the set of all symmetry operations of some molecule, and * denotes the composition (repeated application) of symmetry operations.

This group is called the point group of that molecule, because the set of symmetry operations leave at least one point fixed (though for some symmetries an entire axis or an entire plane remains fixed). In other words, a point group is a group that summarizes all symmetry operations that all molecules in that category have.[8] The symmetry of a crystal, by contrast, is described by a space group of symmetry operations, which includes translations in space.

One can determine the symmetry operations of the point group for a particular molecule by considering the geometrical symmetry of its molecular model. However, when one USES a point group, the operations in it are not to be interpreted in the same way. Instead the operations are interpreted as rotating and/or reflecting the vibronic (vibration-electronic) coordinates and these operations commute with the vibronic Hamiltonian. They are "symmetry operations" for that vibronic Hamiltonian. The point group is used to classify by symmetry the vibronic eigenstates. The symmetry classification of the rotational levels, the eigenstates of the full (rovibronic nuclear spin) Hamiltonian, requires the use of the appropriate permutation-inversion group as introduced by Longuet-Higgins.[9] The relation between point groups and permutation-inversion groups is explained in this pdf file Link .

Examples of point groups

Assigning each molecule a point group classifies molecules into categories with similar symmetry properties. For example, PCl3, POF3, XeO3, and NH3 all share identical symmetry operations.[10] They all can undergo the identity operation E, two different C3 rotation operations, and three different σv plane reflections without altering their identities, so they are placed in one point group, C3v, with order 6.[11] Similarly, water (H2O) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) also share identical symmetry operations. They both undergo the identity operation E, one C2 rotation, and two σv reflections without altering their identities, so they are both placed in one point group, C2v, with order 4.[12] This classification system helps scientists to study molecules more efficiently, since chemically related molecules in the same point group tend to exhibit similar bonding schemes, molecular bonding diagrams, and spectroscopic properties.[8]

Common point groups

The following table contains a list of point groups labelled using the Schoenflies notation, which is common in chemistry and molecular spectroscopy. The description of structure includes common shapes of molecules, which can be explained by the VSEPR model.

| Point group | Symmetry operations | Simple description of typical geometry | Example 1 | Example 2 | Example 3 |

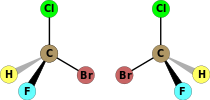

| C1 | E | no symmetry, chiral |  bromochlorofluoromethane (both enantiomers shown) |

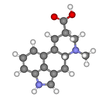

lysergic acid |

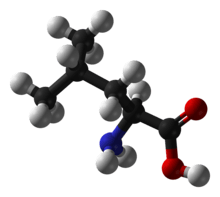

L-leucine and most other α-amino acids except glycine |

| Cs | E σh | mirror plane, no other symmetry |  thionyl chloride |

hypochlorous acid |

chloroiodomethane |

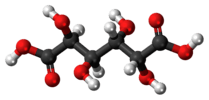

| Ci | E i | inversion center |  meso-tartaric acid |

mucic acid (meso-galactaric acid) |

(S,R) 1,2-dibromo-1,2-dichloroethane (anti conformer) |

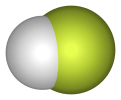

| C∞v | E 2C∞ ∞σv | linear |  hydrogen fluoride (and all other heteronuclear diatomic molecules) |

nitrous oxide (dinitrogen monoxide) |

hydrocyanic acid (hydrogen cyanide) |

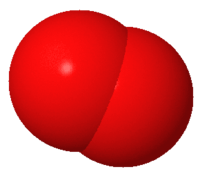

| D∞h | E 2C∞ ∞σi i 2S∞ ∞C2 | linear with inversion center |  oxygen (and all other homonuclear diatomic molecules) |

carbon dioxide |

acetylene (ethyne) |

| C2 | E C2 | "open book geometry," chiral |  hydrogen peroxide |

hydrazine |

tetrahydrofuran (twist conformation) |

| C3 | E C3 | propeller, chiral |  triphenylphosphine |

triethylamine |

phosphoric acid |

| C2h | E C2 i σh | planar with inversion center, no vertical plane |  trans-1,2-dichloroethylene |

-Dinitrogen-difluoride-3D-balls.png) trans-dinitrogen difluoride |

trans-azobenzene |

| C3h | E C3 C32 σh S3 S35 | propeller |  boric acid |

phloroglucinol (1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene) |

|

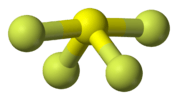

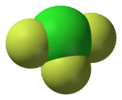

| C2v | E C2 σv(xz) σv'(yz) | angular (H2O) or see-saw (SF4) or T-shape (ClF3) |  water |

sulfur tetrafluoride |

chlorine trifluoride |

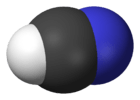

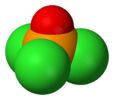

| C3v | E 2C3 3σv | trigonal pyramidal |  ammonia |

phosphorus oxychloride |

4-3D-balls.png) cobalt tetracarbonyl hydride, HCo(CO)4 |

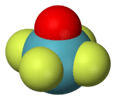

| C4v | E 2C4 C2 2σv 2σd | square pyramidal |  xenon oxytetrafluoride |

pentaborane(9), B5H9 |

nitroprusside anion [Fe(CN)5(NO)]2− |

| C5v | E 2C5 2C52 5σv | 'milking stool' complex | .png) Ni(C5H5)(NO) |

corannulene |

|

| D2 | E C2(x) C2(y) C2(z) | twist, chiral |  biphenyl (skew conformation) |

twistane (C10H16) |

cyclohexane twist conformation |

| D3 | E C3(z) 3C2 | triple helix, chiral | cobalt(III)-chloride-3D-balls-by-AHRLS-2012.png) Tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) cation |

ferrate(III)-3D-balls.png) tris(oxalato)iron(III) anion |

|

| D2h | E C2(z) C2(y) C2(x) i σ(xy) σ(xz) σ(yz) | planar with inversion center, vertical plane |  ethylene |

pyrazine |

diborane |

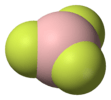

| D3h | E C3 3C2 σh 2S3 3σv | trigonal planar or trigonal bipyramidal |  boron trifluoride |

phosphorus pentachloride |

cyclopropane |

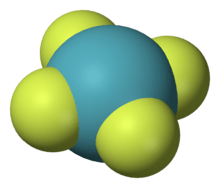

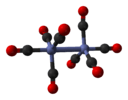

| D4h | E 2C4 C2 2C2' 2C2 i 2S4 σh 2σv 2σd | square planar |  xenon tetrafluoride |

-3D-balls.png) octachlorodimolybdate(II) anion |

.png) Trans-[CoIII(NH3)4Cl2]+ (excluding H atoms) |

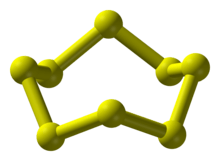

| D5h | E 2C5 2C52 5C2 σh 2S5 2S53 5σv | pentagonal |  cyclopentadienyl anion |

ruthenocene |

C70 |

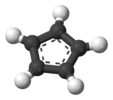

| D6h | E 2C6 2C3 C2 3C2' 3C2‘’ i 2S3 2S6 σh 3σd 3σv | hexagonal |  benzene |

chromium-from-xtal-2006-3D-balls-A.png) bis(benzene)chromium |

coronene (C24H12) |

| D7h | E C7 S7 7C2 σh 7σv | heptagonal |  tropylium (C7H7+) cation |

||

| D8h | E C8 C4 C2 S8 i 8C2 σh 4σv 4σd | octagonal |  cyclooctatetraenide (C8H82−) anion |

uranocene |

|

| D2d | E 2S4 C2 2C2' 2σd | 90° twist |  allene |

tetrasulfur tetranitride |

_excited_state.svg.png) diborane(4) (excited state) |

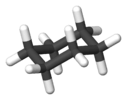

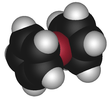

| D3d | E 2C3 3C2 i 2S6 3σd | 60° twist |  ethane (staggered rotamer) |

dicobalt octacarbonyl (non-bridged isomer) |

cyclohexane chair conformation |

| D4d | E 2S8 2C4 2S83 C2 4C2' 4σd | 45° twist |  sulfur (crown conformation of S8) |

dimanganese decacarbonyl (staggered rotamer) |

octafluoroxenate ion (idealised geometry) |

| D5d | E 2C5 2C52 5C2 i 3S103 2S10 5σd | 36° twist |  ferrocene (staggered rotamer) |

||

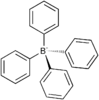

| S4 | E 2S4 C2 |  tetraphenylborate anion |

|||

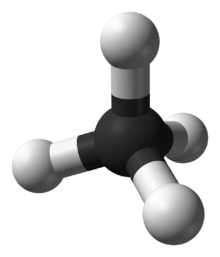

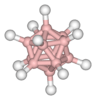

| Td | E 8C3 3C2 6S4 6σd | tetrahedral |  methane |

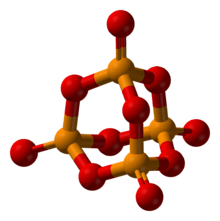

phosphorus pentoxide |

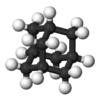

adamantane |

| Th | E 4C3 4C32 i 3C2 4S6 4S65 3σh | pyritohedron | |||

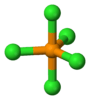

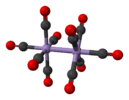

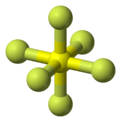

| Oh | E 8C3 6C2 6C4 3C2 i 6S4 8S6 3σh 6σd | octahedral or cubic |  sulfur hexafluoride |

molybdenum hexacarbonyl |

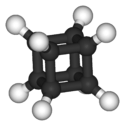

cubane |

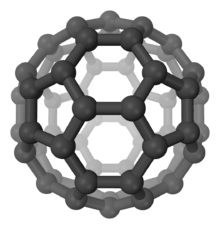

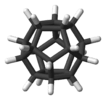

| Ih | E 12C5 12C52 20C3 15C2 i 12S10 12S103 20S6 15σ | icosahedral or dodecahedral |  Buckminsterfullerene |

dodecaborate anion |

dodecahedrane |

Representations

The symmetry operations can be represented in many ways. A convenient representation is by matrices. For any vector representing a point in Cartesian coordinates, left-multiplying it gives the new location of the point transformed by the symmetry operation. Composition of operations corresponds to matrix multiplication. Within a point group, a multiplication of the matrices of two symmetry operations leads to a matrix of another symmetry operation in the same point group.[8] For example, in the C2v example this is:

Although an infinite number of such representations exist, the irreducible representations (or "irreps") of the group are commonly used, as all other representations of the group can be described as a linear combination of the irreducible representations.

Character tables

For each point group, a character table summarizes information on its symmetry operations and on its irreducible representations. As there are always equal numbers of irreducible representations and classes of symmetry operations, the tables are square.

The table itself consists of characters that represent how a particular irreducible representation transforms when a particular symmetry operation is applied. Any symmetry operation in a molecule's point group acting on the molecule itself will leave it unchanged. But, for acting on a general entity, such as a vector or an orbital, this need not be the case. The vector could change sign or direction, and the orbital could change type. For simple point groups, the values are either 1 or −1: 1 means that the sign or phase (of the vector or orbital) is unchanged by the symmetry operation (symmetric) and −1 denotes a sign change (asymmetric).

The representations are labeled according to a set of conventions:

- A, when rotation around the principal axis is symmetrical

- B, when rotation around the principal axis is asymmetrical

- E and T are doubly and triply degenerate representations, respectively

- when the point group has an inversion center, the subscript g (German: gerade or even) signals no change in sign, and the subscript u (ungerade or uneven) a change in sign, with respect to inversion.

- with point groups C∞v and D∞h the symbols are borrowed from angular momentum description: Σ, Π, Δ.

The tables also capture information about how the Cartesian basis vectors, rotations about them, and quadratic functions of them transform by the symmetry operations of the group, by noting which irreducible representation transforms in the same way. These indications are conventionally on the righthand side of the tables. This information is useful because chemically important orbitals (in particular p and d orbitals) have the same symmetries as these entities.

The character table for the C2v symmetry point group is given below:

| C2v | E | C2 | σv(xz) | σv'(yz) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | z | x2, y2, z2 |

| A2 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | Rz | xy |

| B1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | x, Ry | xz |

| B2 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | y, Rx | yz |

Consider the example of water (H2O), which has the C2v symmetry described above. The 2px orbital of oxygen has B1 symmetry as in the fourth row of the character table above, with x in the sixth column). It is oriented perpendicular to the plane of the molecule and switches sign with a C2 and a σv'(yz) operation, but remains unchanged with the other two operations (obviously, the character for the identity operation is always +1). This orbital's character set is thus {1, −1, 1, −1}, corresponding to the B1 irreducible representation. Likewise, the 2pz orbital is seen to have the symmetry of the A1 irreducible representation (i.e.: none of the symmetry operations change it), 2py B2, and the 3dxy orbital A2. These assignments and others are noted in the rightmost two columns of the table.

Historical background

Hans Bethe used characters of point group operations in his study of ligand field theory in 1929, and Eugene Wigner used group theory to explain the selection rules of atomic spectroscopy.[13] The first character tables were compiled by László Tisza (1933), in connection to vibrational spectra. Robert Mulliken was the first to publish character tables in English (1933), and E. Bright Wilson used them in 1934 to predict the symmetry of vibrational normal modes.[14] The complete set of 32 crystallographic point groups was published in 1936 by Rosenthal and Murphy.[15]

Molecular nonrigidity

Point groups are useful for describing rigid molecules which undergo only small oscillations about a single equilibrium geometry, and for which the distorting effects of molecular rotation can be ignored, so that the symmetry operations all correspond to simple geometrical operations. However Longuet-Higgins has introduced a more general type of symmetry group suitable not only for rigid molecules but also for non-rigid molecules that tunnel between equivalent geometries (called versions) and which can also allow for the distorting effects of molecular rotation.[9][16] These groups are known as permutation-inversion groups, because the symmetry operations in them are energetically feasible permutations of identical nuclei, or inversion with respect to the center of mass, or a combination of the two.

For example, ethane (C2H6) has three equivalent staggered conformations. Tunneling between the conformations occurs at ordinary temperatures by internal rotation of one methyl group relative to the other. This is not a rotation of the entire molecule about the C3 axis. Although each conformation has D3d symmetry, as in the table above, description of the internal rotation and associated quantum states and energy levels requires the more complete permutation-inversion group G36.

Similarly, ammonia (NH3) has two equivalent pyramidal (C3v) conformations which are interconverted by the process known as nitrogen inversion. This is not an inversion in the sense used for point group symmetry operations of rigid molecules (i.e., the inversion of vibrational displacements and electronic coordinates in the center of mass) since NH3 has no inversion center. Rather it the inversion of all nuclei and electrons in the center of mass (close to the nitrogen atom), which happens to be energetically feasible for this molecule. The appropriate permutation-inversion group to be used in this situation is D3h(M) which is isomorphic with the point group D3h.

Additionally, as examples, the methane (CH4) and H3+ molecules have highly symmetric equilibrium structures with Td and D3h point group symmetries respectively; they lack permanent electric dipole moments but they do have very weak pure rotation spectra because of rotational centrifugal distortion.[17][18] The permutation-inversion groups required for the complete study of CH4 and H3+ are Td(M) and D3h(M), respectively.

A second and less general approach to the symmetry of nonrigid molecules is due to Altmann.[19][20] In this approach the symmetry groups are known as Schrödinger supergroups and consist of two types of operations (and their combinations): (1) the geometric symmetry operations (rotations, reflections, inversions) of rigid molecules, and (2) isodynamic operations, which take a nonrigid molecule into an energetically equivalent form by a physically reasonable process such as rotation about a single bond (as in ethane) or a molecular inversion (as in ammonia).[20]

See also

- Crystallographic point group

- Point groups in three dimensions

- Symmetry of diatomic molecules

- Symmetry in quantum mechanics

References

- Quantum Chemistry, Third Edition John P. Lowe, Kirk Peterson ISBN 0-12-457551-X

- Physical Chemistry: A Molecular Approach by Donald A. McQuarrie, John D. Simon ISBN 0-935702-99-7

- The chemical bond 2nd Ed. J.N. Murrell, S.F.A. Kettle, J.M. Tedder ISBN 0-471-90760-X

- Physical Chemistry P.W. Atkins and J. de Paula (8th ed., W.H. Freeman 2006) ISBN 0-7167-8759-8, chap.12

- G. L. Miessler and D. A. Tarr Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed., Pearson/Prentice Hall 1998) ISBN 0-13-841891-8, chap.4.

- "Symmetry Operations and Character Tables". University of Exeter. 2001. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- LEO Ergebnisse für "einheit"

- Pfenning, Brian (2015). Principles of Inorganic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118859025.

- Longuet-Higgins, H.C. (1963). "The symmetry groups of non-rigid molecules". Molecular Physics. 6 (5): 445–460. Bibcode:1963MolPh...6..445L. doi:10.1080/00268976300100501.

- Pfennig, Brian. Principles of Inorganic Chemistry. Wiley. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-118-85910-0.

- pfennig, Brian. Principles of Inorganic Chemistry. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-85910-0.

- Miessler, Gary. Inorganic Chemistry. Pearson. ISBN 9780321811059.

- Group Theory and its application to the quantum mechanics of atomic spectra, E. P. Wigner, Academic Press Inc. (1959)

- Correcting Two Long-Standing Errors in Point Group Symmetry Character Tables Randall B. Shirts J. Chem. Educ. 2007, 84, 1882. Abstract

- Rosenthal, Jenny E.; Murphy, G. M. (1936). "Group Theory and the Vibrations of Polyatomic Molecules". Rev. Mod. Phys. 8: 317–346. Bibcode:1936RvMP....8..317R. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.8.317.

- Philip R. Bunker and Per Jensen (2005), Fundamentals of Molecular Symmetry (Institute of Physics Publishing) ISBN 0-7503-0941-5

- Watson, J.K.G (1971). "Forbidden rotational spectra of polyatomic molecules". Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy. 40 (3): 546–544. Bibcode:1971JMoSp..40..536W. doi:10.1016/0022-2852(71)90255-4.

- Oldani, M.; et al. (1985). "Pure rotational spectra of methane and methane-d4 in the vibrational ground state observed by microwave Fourier transform spectroscopy". Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy. 110 (1): 93–105. Bibcode:1985JMoSp.110...93O. doi:10.1016/0022-2852(85)90215-2.

- Altmann S.L. (1977) Induced Representations in Crystals and Molecules, Academic Press

- Flurry, R.L. (1980) Symmetry Groups, Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-880013-8, pp.115-127

External links

- Point group symmetry @ Newcastle University

- Molecular symmetry @ Imperial College London

- Molecular Symmetry Online @ The Open University of Israel

- Molecular Point Group Symmetry Tables

- Symmetry @ Otterbein

- An internet lecture course on molecular symmetry @ Bergische Universitaet

- Character tables for point groups for chemistry Link

- A pdf file explaining the relation between Point Groups and Permutation-Inversion Groups Link