Maasai Mara

Maasai Mara, also known as Masai Mara, and locally simply as The Mara, is a large game reserve in Narok County, Kenya, contiguous with the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania. It is named in honor of the Maasai people, the ancestral inhabitants of the area. Their description of the area when looked at from afar: "Mara" means "spotted" in the local Maasai language, due to the many trees which dot the landscape.

| Maasai Mara National Reserve | |

|---|---|

Typical "spotted" Maasai Mara scenery | |

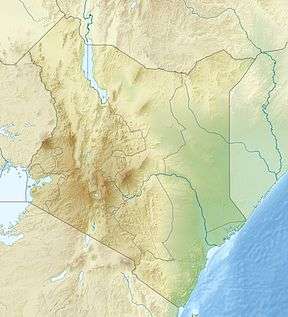

Location of Maasai Mara National Reserve | |

| Location | Kenya, Rift Valley Province |

| Nearest town | Narok |

| Coordinates | 1°29′24″S 35°8′38″E |

| Area | 1,510 km2 (580 sq mi)[1] |

| Established | 1961 |

| Governing body | Trans-Mara and Narok County Councils |

It is one of the most famous wilderness areas in Africa, world-renowned for its exceptional populations of lions, leopards, cheetahs and elephant. It also hosts the Great Migration, which secured it as one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa, and as one of the ten natural travel wonders of the world.

The Greater Mara Ecosystem encompasses areas known as the Maasai Mara National Reserve, the Mara Triangle, and several Maasai Conservancies, including: Koiyaki, Lemek, Ol Chorro Oirowua, Olkinyei, Siana, Maji Moto, Naikara, Ol Derkesi, Kerinkani, Oloirien, and Kimintet.

History

When it was originally established in 1961 as a wildlife sanctuary the Mara covered only 520 km2 (200 sq mi) of the current area, including the Mara Triangle. The area was extended to the east in 1961 to cover 1,821 km2 (703 sq mi) and converted to a game reserve. The Narok County Council (NCC) took over management of the reserve at this time. Part of the reserve was given National Reserve status in 1974, and the remaining area of 159 km2 (61 sq mi) was returned to local communities. An additional 162 km2 (63 sq mi) were removed from the reserve in 1976, and the park was reduced to 1,510 km2 (580 sq mi) in 1984.[2]

In 1994, the TransMara County Council (TMCC) was formed in the western part of the reserve, and control was divided between the new council and the existing Narok County Council. In May 2001, the not-for-profit Mara Conservancy took over management of the Mara Triangle.[2]

The Maasai people make up a community that spans across northern, central and southern Kenya and northern parts of Tanzania. As pastoralists, the community holds the belief that they own all of the cattle in the world. The Maasai rely off of their lands to sustain their cattle, as well as themselves and their families. Prior to the establishment of the reserve as a protected area for the conservation of wildlife and wilderness, the Maasai were forced to move out of their native lands.

Geography

The total area under conservation in the Greater Maasai Mara ecosystem amounts to almost 1,510 km2 (580 sq mi).[1] It is the northernmost section of the Mara-Serengeti ecosystem, which covers some 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) in Tanzania and Kenya. It is bounded by the Serengeti Park to the south, the Siria / Oloololo escarpment to the west, and Masai pastoral ranches to the north, east and west. Rainfall in the ecosystem increases markedly along a southeast–northwest gradient, varies in space and time, and is markedly bimodal. The Sand, Talek River and Mara River are the major rivers draining the reserve. Shrubs and trees fringe most drainage lines and cover hillslopes and hilltops.

The terrain of the reserve is primarily open grassland with seasonal riverlets. In the south-east region are clumps of the distinctive acacia tree. The western border is the Esoit (Siria) Escarpment of the East African Rift, which is a system of rifts some 5,600 km (3,500 mi) long, from Ethiopia's Red Sea through Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi and into Mozambique. Wildlife tends to be most concentrated here, as the swampy ground means that access to water is always good, while tourist disruption is minimal. The easternmost border is 224 km (139.2 mi) from Nairobi, and hence it is the eastern regions which are most visited by tourists.

Elevation: 1,500–2,180 m (4,920–7,150 ft); Rainfall: 83 mm (3.3 in)/month; Temperature range: 12–30 °C (54–86 °F)

Wildlife

Wildebeest, topi, zebra, and Thomson's gazelle migrate into and occupy the Mara reserve, from the Serengeti plains to the south and Loita Plains in the pastoral ranches to the north-east, from July to October or later. Herds of all three species are also resident in the reserve.

All members of the "Big Five" (lion, leopard, elephant, cape buffalo, and rhinoceros) are found here all year round.[3] The population of black rhinos was fairly numerous until 1960, but it was severely depleted by poaching in the 1970s and early 1980s, dropping to a low of 15 individuals. Numbers have been slowly increasing, but the population was still only up to an estimated 23 in 1999.[4] The Maasai Mara is the only protected area in Kenya with an indigenous black rhino population, unaffected by translocations, and due to its size, is able to support one of the largest populations in Africa[5].

Hippopotami and crocodiles are found in large groups in the Mara and Talek rivers. Hyenas, cheetahs, jackals, and bat-eared foxes can also be found in the reserve.[6] The plains between the Mara River and the Esoit Siria Escarpment are probably the best area for game viewing, in particular regarding lion and cheetah.

Wildebeest are the dominant inhabitants of the Maasai Mara, and their numbers are estimated in the millions. Around July of each year, these animals migrate north from the Serengeti plains in search of fresh pasture, and return to the south around October. The Great Migration is one of the most impressive natural events worldwide, involving some 1,300,000 wildebeest, 500,000 Thomson's gazelles, 97,000 Topi, 18,000 elands, and 200,000 zebras.[7]

Antelopes can be found, including Grant's gazelles, impalas, duikers and Coke's hartebeests. The plains are also home to the distinctive Masai giraffe. The large roan antelope and the nocturnal bat-eared fox, rarely present elsewhere in Kenya, can be seen within the reserve borders.

More than 470 species of birds have been identified in the park, many of which are migrants, with almost 60 species being raptors.[8] Birds that call this area home for at least part of the year include: vultures, marabou storks, secretary birds, hornbills, crowned cranes, ostriches, long-crested eagles, African pygmy-falcons and the lilac-breasted roller, which is the national bird of Kenya.

Administration

The Maasai Mara is administered by the Narok County government. The more visited eastern part of the park known as the Maasai Mara National Reserve is managed by the Narok County Council. The Mara Triangle in the western part is managed by the Trans-Mara county council, which has contracted management to the Mara Conservancy since the early 2000s.

The outer areas are conservancies that are administered by Group Ranch Trusts of the Masai community who also have their own rangers for patrolling the conservation areas. Although there has been a rise in fencing on private land in recent years, the wildlife roam freely across both the reserve and conservancies.

Research

The Maasai Mara is a major research centre for the spotted hyena. With two field offices in the Mara, the Michigan State University based Kay E. Holekamp Lab studies the behavior and physiology of this predator, as well as doing comparison studies between large predators in the Mara Triangle and their counterparts in the eastern part of the Mara.[9]

A flow assessment and trans-boundary river basin management plan between Kenya and Tanzania was completed for the river to sustain the ecosystem and the basic needs of 1 million people who depend on its water.[10]

The Mara Predator Project also operates in the Maasai Mara, cataloging and monitoring lion populations throughout the region.[11] Concentrating on the northern conservancies where communities coexist with wildlife, the project aims to identify population trends and responses to changes in land management, human settlements, livestock movements and tourism. Sara Blackburn, the project manager, works in partnership with a number of lodges in the region by training guides to identify lions and report sightings. Guests are also encouraged to participate in the project by photographing lions seen on game drives. An online database of individual lions is openly accessible, and features information on project participants and focus areas.

Since October 2012, the Mara-Meru Cheetah Project[12] has worked in the Mara monitoring cheetah population, estimating population status and dynamics, and evaluating the predator impact and human activity on cheetah behavior and survival. The head of the Project, Elena Chelysheva, was working in 2001-2002 as Assistant Researcher at the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) Maasai-Mara Cheetah Conservation Project. At that time, she developed original method of cheetah identification based on visual analysis of the unique spot patterns on front limbs (from toes to shoulder) and hind limbs (from toes to the hip), and spots and rings on the tail.[13] Collected over the years, photographic data allows the project team to trace kinship between generations and build Mara cheetah pedigree. The data collected helps to reveal parental relationship between individuals, survival rate of cubs, cheetah lifespan and personal reproductive history. This work has never been done before and the team is sharing results with the Mara stakeholders and respondents. The ongoing research is a follow-up study, which will compare results with the previous one in terms of cheetah population status and effect of human activity on cheetah behavior and surviving. The project is working in affiliation with Kenya Wildlife Service, Narok and Transmara County Councils and with assistance of Coordinator of Maasai-Mara Cultural Village Tour Association (MMCVTA). The team is cooperating with Mara Hyena Project and working with managers and driver-guides from over 30 different Mara camps and lodges. Rangers and driver/guides are trained in cheetah identification techniques and provided with catalogues of the Mara cheetahs.

Visiting

Game parks are a major source of foreign currency for Kenya. Entry fees are currently US$80 for adult non-East African Residents and $30 for children.[14] There are a number of lodges and tented camps catering for tourists inside or bordering the Reserve and within the Conservancy borders.

Although one third of the whole Masai Mara, The Mara Triangle has only two lodges within its boundaries (compared to the numerous camps and lodges on the Narok side) and has well maintained, all weather roads. The rangers patrol regularly which means that there is less poaching and excellent game viewing. There is also strict control over vehicle numbers around animal sightings, allowing for a better experience when out on a game drive.

There are several airfields which serve the camps and lodges in the Maasai Mara, including Mara Serena Airport, Musiara Airport and Keekorok, Kichwa Tembo, Ngerende Airport, Ol Kiombo and Angama Mara Airfield, and several airlines such as SafariLink and AirKenya fly scheduled services from Nairobi and elsewhere multiple times a day. Helicopter flights over the reserve are limited to a minimum height of 1,500 ft.

While visiting national reserves or parks in Eastern Africa, it's important to research the history of spaces as a tourist, to gain a better understanding and obtain a deeper knowledge of the area. The continent of Africa in particular was affected in a negative manner by colonization, which has long lasting effects on the history of the continent as a whole. Tourists have gained a reputation for coming to these African landscapes, taking a photo and then quickly fleeing, while leaving their ecological waste and carbon footprint behind. In attempts to gain a better reputation for tourist, researching spaces and acknowledging the past history of Kenya and Eastern Africa is essential in mitigating this issue.

Big Cat Diary

The BBC Television show titled "Big Cat Diary" was filmed in both the Reserve and Maasai Conservancy areas of the Mara. The show followed the lives of the big cats living in the reserve. The show highlighted scenes from the Reserve's Musiara marsh area and the Leopard Gorge, the Fig Tree Ridge areas and the Mara River, separating the Serengeti and the Maasai Mara.

Photography competition

In 2018, the Angama Foundation, a non-profit affiliated with Angama Mara, one of the Mara's luxury safari camps, launched the Greatest Maasai Mara Photographer of the Year competition, showcasing the Mara as a year-round destination and raise funds for conservation initiatives active in the Mara.[15] The inaugural winner was British photographer Anup Shah.[16] The 2019 winner was Lee-Anne Robertson from South Africa.[17]

Threats

A study funded by WWF and conducted by ILRI between 1989 and 2003 monitored hoofed species in the Mara on a monthly basis, and found that losses were as high as 75 percent for giraffes, 80 percent for common warthogs, 76 percent for hartebeest, and 67 percent for impala. The study blames the loss of animals on increased human settlement in and around the reserve. The higher human population density leads to an increased number of livestock grazing in the park and an increase in poaching. The article claims, "The study provides the most detailed evidence to date on the declines in the ungulate (hoofed animals) populations in the Mara and how this phenomenon is linked to the rapid expansion of human populations near the boundaries of the reserve."[18]

In the neighbouring Serengeti National Park, a proposed 50-kilometre (31 mi) road from Musoma to Arusha, with tarmac touching the Serengeti, is raising criticism from scientists who say that the road will disrupt the annual migration of the wildebeest, and that this disruption would affect predators such as lions, cheetahs and African wild dogs, as well as the grasslands themselves.[19]

According to CCTV "The route is expected to carry 800 vehicles a day, mostly trucks, by 2015 and 3000 vehicles a day an average of one every 30 seconds by 2035, a campaign promise made by Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete in 2005".[20] In late June 2011 the Tanzanian government decided to cancel the Serengeti road plan due to global outcry.[21]

The rise of local populations in areas neighbouring the reserve has led to the formation of conservation organisations such as the Mara Elephant Project who aim to ensure the peaceful and prosperous co-existence of humans alongside wildlife. Human wildlife conflict is seen as a leading threat to the reserve as the population continues to grow.[22]

Gallery

Hot air balloons over Maasai Mara at sunrise

Hot air balloons over Maasai Mara at sunrise Male lion

Male lion African leopard climbing down a tree

African leopard climbing down a tree

Masai giraffes in the open grassland

Masai giraffes in the open grassland Wildebeest with zebras in distance

Wildebeest with zebras in distance

Storm gathering

Storm gathering

See also

- Olare Orok Conservancy

- List of national parks of Kenya

- Serengeti National Park

- Narok County

- Republic of Kenya

References

- Protected Planet (2018). "Masai Mara". United Nations Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- Walpole 2003, p. X

- "About the Masai Mara National Reserve | National Geographic Lodges". National Geographic Unique Lodges of the World. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Walpole 2003, p. 17

- "Black Rhino". Mara Conservancy. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Masai Mara National Reserve". guideforafrica.com. Guide for Africa. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "The Greatest Show on Earth". The Mara Conservancy. Archived from the original on 19 October 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- "Masai Mara Bird List". maratriangle.org. The Mara Conservancy. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- "Research". The Mara Conservancy. Archived from the original on 17 October 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- McClain, M.E., Subalusky, A.L., Anderson, E.P., Dessu, S.B., Melesse, A.M., Ndomba, P.M., Mtamba, J.O., Tamatamah, R.A. and Mligo, C. (2014). "Comparing flow regime, channel hydraulics, and biological communities to infer flow–ecology relationships in the Mara River of Kenya and Tanzania". Hydrological Sciences Journal. 59 (3−4): 801−819. doi:10.1080/02626667.2013.853121.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Mara Predator Project

- "Mara Meru Cheetah Project". marameru.org. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Cat News #41, 2004

- "The Mara Conservancy – Park fees". maratriangle.org. Mara Conservancy. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- "The Greatest Masai Mara Photographer of the Year". Angama Foundation.

- "The greatest Maasai Mara Photographer of the year winner announcement". Nomad. 2018.

- "Maasai Mara 2019 Photographer of the Year announced". Tourism Update. 2019.

- Ogutu, J. O.; Piepho, H. P.; Dublin, H. T; Bhola, N.; Reid, R. S. (May 2009). "Dynamics of Mara-Serengeti ungulates in relation to land use changes". Journal of Zoology. 278 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00536.x.

- "Tanzania's Serengeti National Park facing 'collapse' due to highway plans". African Conservation Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 October 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- Jianfeng, Z. (2012). "Highway threatens Serengeti ecosystem in Tanzania". CCTV. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- "Serengeti road cancelled". Mongabay Environmental News. 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Mara Elelphant Project https://maraelephantproject.org/. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Walpole, M.; Karanja, G.G.; Sitati, N.W.; Leader-Williams (2003). Wildlife and People: Conflict and Conservation in Masai Mara, Kenya (PDF). Wildlife and Development Series. 14. London: International Institute for Environment and Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2006. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maasai Mara. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Maasai Mara National Reserve. |