Janis Joplin

Janis Lyn Joplin (January 19, 1943 – October 4, 1970) was an American singer-songwriter who sang rock, soul and blues music. One of the most successful and widely known rock stars of her era, she was noted for her powerful mezzo-soprano vocals[1] and "electric" stage presence.[2][3][4]

Janis Joplin | |

|---|---|

.png) Joplin performing in 1969 | |

| Born | Janis Lyn Joplin January 19, 1943 Port Arthur, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | October 4, 1970 (aged 27) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Heroin overdose |

| Resting place | Cremated; ashes scattered into the Pacific Ocean |

| Other names | Pearl |

| Education | Lamar State College of Technology, University of Texas at Austin, Port Arthur College |

| Occupation | Singer-songwriter |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1962–1970 |

| Labels | Columbia Records |

| Associated acts |

|

| Website | janisjoplin |

| Signature | |

| |

In 1967, Joplin rose to fame following an appearance at Monterey Pop Festival, where she was the lead singer of the then little-known San Francisco psychedelic rock band Big Brother and the Holding Company.[5][6][7] After releasing two albums with the band, she left Big Brother to continue as a solo artist with her own backing groups, first the Kozmic Blues Band and then the Full Tilt Boogie Band. She appeared at the Woodstock festival and the Festival Express train tour. Five singles by Joplin reached the Billboard Hot 100, including a cover of the Kris Kristofferson song "Me and Bobby McGee", which reached number 1 in March 1971.[8] Her most popular songs include her cover versions of "Piece of My Heart", "Cry Baby", "Down on Me", "Ball and Chain", and "Summertime"; and her original song "Mercedes Benz", her final recording.[9][10]

Joplin died of an accidental heroin overdose in 1970 at age 27, after releasing three albums. A fourth album, Pearl, was released in January 1971, just over three months after her death. It reached number one on the Billboard charts. She was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995. Rolling Stone ranked Joplin number 46 on its 2004 list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time[11] and number 28 on its 2008 list of 100 Greatest Singers of All Time. She remains one of the top-selling musicians in the United States, with Recording Industry Association of America certifications of 15.5 million albums sold.[12]

Early life

1943–1961: Early years

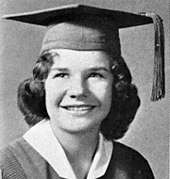

Janis Lyn Joplin was born in Port Arthur, Texas, on January 19, 1943,[13] to Dorothy Bonita East (1913–1998), a registrar at a business college, and her husband, Seth Ward Joplin (1910–1987), an engineer at Texaco. She had two younger siblings, Michael and Laura. The family belonged to the Churches of Christ denomination.[14]

Her parents felt that Janis needed more attention than their other children.[15] As a teenager, Joplin befriended a group of outcasts, one of whom had albums by blues artists Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, and Lead Belly, whom Joplin later credited with influencing her decision to become a singer.[16] She began singing blues and folk music with friends at Thomas Jefferson High School.[17][18][19][20] Former Oklahoma State University and Dallas Cowboys Head Coach Jimmy Johnson was a high school classmate of Joplin.[21]

Joplin stated that she was ostracized and bullied in high school.[16] As a teen, she became overweight and suffered from acne, leaving her with deep scars that required dermabrasion.[15][22][23] Other kids at high school would routinely taunt her and call her names like "pig," "freak," "nigger lover," or "creep." [15] She stated, "I was a misfit. I read, I painted, I thought. I didn't hate niggers."[24]

Joplin graduated from high school in 1960 and attended Lamar State College of Technology in Beaumont, Texas, during the summer[22] and later the University of Texas at Austin (UT), though she did not complete her college studies.[25] The campus newspaper, The Daily Texan, ran a profile of her in the issue dated July 27, 1962, headlined "She Dares to Be Different."[25] The article began, "She goes barefooted when she feels like it, wears Levis to class because they're more comfortable, and carries her autoharp with her everywhere she goes so that in case she gets the urge to break into song, it will be handy. Her name is Janis Joplin."[25] While at UT she performed with a folk trio called the Waller Creek Boys and frequently socialized with the staff of the campus humor magazine The Texas Ranger.[26] According to Freak Brothers cartoonist Gilbert Shelton, who befriended her, she used to sell The Texas Ranger, which contained some of Shelton's early comic books, on the campus.

Career

1962–1965: Early recordings

Joplin cultivated a rebellious manner and styled herself partly after her female blues heroines and partly after the Beat poets. Her first song, "What Good Can Drinkin' Do", was recorded on tape in December 1962 at the home of a fellow University of Texas student.[27]

She left Texas in January 1963 ("Just to get away," she said, "because my head was in a much different place"),[28] hitchhiking with her friend Chet Helms to North Beach, San Francisco. Still in San Francisco in 1964, Joplin and future Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen recorded a number of blues standards, which incidentally featured Kaukonen's wife Margareta using a typewriter in the background. This session included seven tracks: "Typewriter Talk", "Trouble in Mind", "Kansas City Blues", "Hesitation Blues", "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out", "Daddy, Daddy, Daddy", and "Long Black Train Blues", and was released long after Joplin's death as the bootleg album The Typewriter Tape.

In 1963, Joplin was arrested in San Francisco for shoplifting. During the two years that followed, her drug use increased and she acquired a reputation as a "speed freak" and occasional heroin user.[13][16][22] She also used other psychoactive drugs and was a heavy drinker throughout her career; her favorite alcoholic beverage was Southern Comfort.

In May 1965, Joplin's friends in San Francisco, noticing the detrimental effects on her from regularly injecting methamphetamine (she was described as "skeletal"[16] and "emaciated"[13]), persuaded her to return to Port Arthur. During that month, her friends threw her a bus-fare party so she could return to her parents in Texas.[13] Five years later, Joplin told Rolling Stone magazine writer David Dalton the following about her first stint in San Francisco: "I didn't have many friends and I didn't like the ones I had."[29]

Back in Port Arthur in the spring of 1965, after Joplin's parents noticed her weight of 88 pounds (40 kg),[23] she changed her lifestyle. She avoided drugs and alcohol, adopted a beehive hairdo, and enrolled as an anthropology major at Lamar University in nearby Beaumont, Texas. During her time at Lamar University, she commuted to Austin to sing solo, accompanying herself on acoustic guitar. One of her performances was at a benefit by local musicians for Texas bluesman Mance Lipscomb, who was suffering with ill health.

Joplin became engaged to Peter de Blanc in the fall of 1965.[30] She had begun a relationship with him toward the end of her first stint in San Francisco.[30] Now living in New York where he worked with IBM computers,[31][32] he visited her to ask her father for her hand in marriage.[33] Joplin and her mother began planning the wedding.[23][33] De Blanc, who traveled frequently,[30] ended the engagement soon afterward.[23][30]

In 1965 and 1966, Joplin commuted from her family's Port Arthur home to Beaumont, Texas, where she had regular sessions with a psychiatric social worker named Bernard Giarritano[23] at a counseling agency that was funded by the United Fund, which after her death changed its name to the United Way.[13] Interviewed by biographer Myra Friedman after his client's death, Giarritano said Joplin had been baffled by how she could pursue a professional career as a singer without relapsing into drugs, and her drug-related memories from immediately prior to returning to Port Arthur continued to frighten her.[23] Joplin sometimes brought an acoustic guitar with her to her sessions with Giarritano, and people in other offices within the building could hear her singing.[13]

Giarritano tried to reassure her that she did not have to use narcotics in order to succeed in the music business.[23] She also said that if she were to avoid singing professionally, she would have to become a keypunch operator (as she had done a few years earlier) or a secretary, and then a wife and mother, and she would have to become very similar to all the other women in Port Arthur.[23]

Approximately a year before Joplin joined Big Brother and the Holding Company, she recorded seven studio tracks with her acoustic guitar. Among the songs she recorded were her original composition for the song "Turtle Blues" and an alternate version of "Cod'ine" by Buffy Sainte-Marie. These tracks were later issued as a new album in 1995, titled This is Janis Joplin 1965 by James Gurley.

1966–1969: Various bands

In 1966, Joplin's bluesy vocal style attracted the attention of the San Francisco-based psychedelic rock band Big Brother and the Holding Company, which had gained some renown among the nascent hippie community in Haight-Ashbury.[34] She was recruited to join the group by Chet Helms, a promoter who had known her in Texas and who at the time was managing Big Brother. Helms sent his friend Travis Rivers to find her in Austin, Texas, where she had been performing with her acoustic guitar, and to accompany her to San Francisco.

Aware of her previous nightmare with drug addiction in San Francisco, Rivers insisted that she inform her parents face-to-face of her plans, and he drove her from Austin to Port Arthur (he waited in his car while she talked with her startled parents) before they began their long drive to San Francisco. Joplin joined Big Brother on June 4, 1966.[35] Her first public performance with them was at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco.

In June, Joplin was photographed at an outdoor concert in San Francisco that celebrated the summer solstice. The image, which was later published in two books by David Dalton, shows her before she relapsed into drugs. Due to persistent persuading by keyboardist and close friend Stephen Ryder, Joplin avoided drugs for several weeks. She made Travis Rivers, with whom she shared an apartment upon their arrival in San Francisco, promise that using needles would not be allowed there.[23] When bandmate Dave Getz accompanied her from a rehearsal to her home, Rivers was not there, but "two or three" (according to Getz' recollection 25 years later) guests whom Rivers had invited were in the process of injecting drugs.[23] "One of them was about to tie off," recalled Getz.[23] "Janis went nuts! I had never seen anybody explode like that. She was screaming and crying and Travis walked in. She screamed at him: 'We had a pact! You promised me! There wouldn't be any of that in front of me!' I was over my head and I tried to calm her down. I said, 'They're just doing mescaline,' because that's what I thought it was. She said, 'You don't understand! I can't see that! I just can't stand to see that!'"[23]

A San Francisco concert from that summer (1966) was recorded and released in the 1984 album Cheaper Thrills. In July, all five bandmates and guitarist James Gurley's wife Nancy moved to a house in Lagunitas, California, where they lived communally. They often partied with the Grateful Dead, who lived less than two miles away. She had a short relationship and longer friendship with founding member Ron "Pigpen" McKernan.[36]

The band went to Chicago for a four-week engagement in August 1966, then found themselves stranded after the promoter ran out of money when their concerts did not attract the expected audience levels, and he was unable to pay them.[37] In the circumstances the band signed to Bob Shad's record label Mainstream Records; recordings for the label took place in Chicago in September, but these were not satisfactory, and the band returned to San Francisco, continuing to perform live, including at the Love Pageant Rally.[38][39] The band recorded two tracks, "Blindman" and "All Is Loneliness", in Los Angeles, and these were released by Mainstream as a single which did not sell well.[40] After playing at a "happening" in Stanford in early December 1966, the band travelled back to Los Angeles to record ten tracks between December 12 and 14, 1966, produced by Bob Shad, which appeared on the band's debut album in August 1967.[40]

In late 1966, Big Brother switched managers from Chet Helms to Julius Karpen.[16]

One of Joplin's earliest major performances in 1967 was at the Mantra-Rock Dance, a musical event held on January 29 at the Avalon Ballroom by the San Francisco Hare Krishna temple. Janis Joplin and Big Brother performed there along with the Hare Krishna founder Bhaktivedanta Swami, Allen Ginsberg, Moby Grape, and Grateful Dead, donating proceeds to the Krishna temple.[42][43][44] In early 1967, Joplin met Country Joe McDonald of the group Country Joe and the Fish. The pair lived together as a couple for a few months.[13][29] Joplin and Big Brother began playing clubs in San Francisco, at the Fillmore West, Winterland and the Avalon Ballroom. They also played at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, as well as in Seattle, Washington, Vancouver, British Columbia, the Psychedelic Supermarket in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Golden Bear Club in Huntington Beach, California.[29]

The band's debut studio album, Big Brother & the Holding Company, was released by Mainstream Records in August 1967, shortly after the group's breakthrough appearance in June at the Monterey Pop Festival.[28] Two tracks, "Coo Coo" and "The Last Time", were released separately as singles, while the tracks from the previous single, "Blindman" and "All Is Loneliness", were added to the remaining eight tracks.[40] When Columbia Records took over the band's contract and re-released the album, they included "Coo Coo" and "The Last Time", and put "featuring Janis Joplin" on the cover. The debut album spawned four minor hits with the singles "Down on Me", a traditional song arranged by Joplin, "Bye Bye Baby", "Call On Me" and "Coo Coo", on all of which Joplin sang lead vocals.

Two songs from the second of Big Brother's two sets at Monterey, which they played on Sunday, were filmed (their first set, which was on Saturday, was not filmed, though it was audio-recorded). Some sources, including a Joplin biography by Ellis Amburn, claim that she was dressed in thrift store hippie clothes or second-hand Victorian clothes during the band's Saturday set,[16] but still photographs do not appear to have survived. Digitized color film of two songs in the Sunday set, "Combination of the Two" and a version of Big Mama Thornton's "Ball and Chain", appear in the DVD box set of D. A. Pennebaker's documentary Monterey Pop released by The Criterion Collection. She is seen wearing an expensive gold tunic dress with matching pants.[45] They were created for her by San Francisco clothing designer Colin Rose.[45]

Documentary filmmaker Pennebaker inserted two cutaway shots of Cass Elliot of the Mamas & the Papas seated in the audience during Joplin's performance of "Ball and Chain", one in the middle of the song as her eyes, covered by sunglasses, are fixed on Joplin, and also a shot during the applause as she silently mouths "Oh, wow!" and looks at the person seated next to her. Elliot and the audience are seen in sunlight, but Sunday's Big Brother performance was filmed in the evening.[46][47] An explanation has come from Big Brother's road manager John Byrne Cooke, who remembers that Pennebaker discreetly filmed the audience (including Elliot) during Big Brother's Saturday performance when he was not allowed to point a camera at the band.[48]

The prohibition of Pennebaker from filming on Saturday afternoon came from Big Brother's manager Julius Karpen.[48] The band had a bitter argument with Karpen and overruled him as they prepared for their second set that the festival organizers had added on the spur of the moment.[48] Backstage at the festival, the band became acquainted with New York-based talent manager Albert Grossman, but did not sign with him until several months later, firing Karpen at that time.[48]

Only "Ball and Chain" was included in the Monterey Pop film that was released to cinemas throughout the United States in 1969 and shown on television in the 1970s. Those who did not attend the Monterey Pop Festival saw the band's performance of "Combination of the Two" for the first time in 2002 when The Criterion Collection released the box set.

For the remainder of 1967, even after Big Brother signed with Albert Grossman, they performed mainly in California. On February 16, 1968,[49] the group began its first East Coast tour in Philadelphia, and the following day gave their first performance in New York City at the Anderson Theater.[13][16] On April 7, 1968, the last day of their East Coast tour, Joplin and Big Brother performed with Jimi Hendrix, Buddy Guy, Joni Mitchell, Richie Havens, Paul Butterfield, and Elvin Bishop at the "Wake for Martin Luther King, Jr." concert in New York.

Live at Winterland '68, recorded at the Winterland Ballroom on April 12 and 13, 1968, features Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company at the height of their mutual career working through a selection of tracks from their albums. A recording became available to the public for the first time in 1998 when Sony Music Entertainment released the compact disc. One month after the Winterland concert, Owsley Stanley recorded them at the Carousel Ballroom, released in 2012 as Live at the Carousel Ballroom 1968.

On July 31, 1968, Joplin made her first nationwide television appearance when the band performed on This Morning, an ABC daytime 90-minute variety show hosted by Dick Cavett. Shortly thereafter, network employees wiped the videotape, though the audio survives. (In 1969 and 1970, Joplin made three appearances on Cavett's prime-time program. Video was preserved and excerpts have been included in most documentaries about Joplin. Audio of her 1968 appearance has not been used since then.)

Sometime in 1968, the band's billing was changed to "Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company,"[29] and the media coverage given to Joplin generated resentment within the band.[29] The other members of Big Brother thought that Joplin was on a "star trip", while others were telling Joplin that Big Brother was a terrible band and that she ought to dump them.[29] Time magazine called Joplin "probably the most powerful singer to emerge from the white rock movement", and Richard Goldstein wrote for the May 1968 issue of Vogue magazine that Joplin was "the most staggering leading woman in rock ... she slinks like tar, scowls like war ... clutching the knees of a final stanza, begging it not to leave ... Janis Joplin can sing the chic off any listener."[15]

For her first major studio recording, Joplin played a major role in the arrangement and production of the songs that would comprise Big Brother and the Holding Company's second album, Cheap Thrills. During the recording sessions, produced by John Simon, Joplin was said to be the first person to enter the studio and the last person to leave. Footage of Joplin and the band in the studio shows Joplin in great form and taking charge during the recording for "Summertime". The album featured a cover design by counterculture cartoonist Robert Crumb.

Although Cheap Thrills sounded as if it consisted of concert recordings, like on "Combination of the Two" and "I Need a Man to Love", only "Ball and Chain" was actually recorded in front of a paying audience; the rest of the tracks were studio recordings.[13] The album had a raw quality, including the sound of a drinking glass breaking and the broken shards being swept away during the song "Turtle Blues". Cheap Thrills produced very popular hits with "Piece of My Heart" and "Summertime". Together with the premiere of the documentary film Monterey Pop at New York's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts on December 26, 1968,[50] the album launched Joplin as a star.[51] Cheap Thrills reached number one on the Billboard 200 album chart eight weeks after its release, and was number one for eight (nonconsecutive) weeks.[51] The album was certified gold at release and sold over a million copies in the first month of its release.[23][29] The lead single from the album, "Piece of My Heart", reached number 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the fall of 1968.[52]

The band made another East Coast tour during July–August 1968, performing at the Columbia Records convention in Puerto Rico and the Newport Folk Festival. After returning to San Francisco for two hometown shows at the Palace of Fine Arts Festival on August 31 and September 1, Joplin announced that she would be leaving Big Brother. On September 14, 1968, culminating a three-night engagement together at Fillmore West, fans thronged to a concert that Bill Graham publicized as the last official concert of Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company. The opening acts on this night were Chicago (then still called Chicago Transit Authority) and Santana.

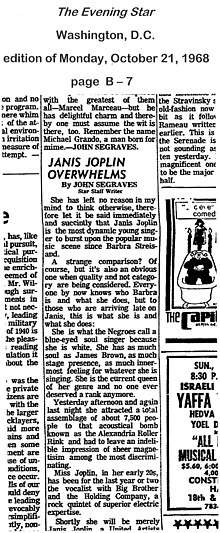

Despite Graham's announcement that the Fillmore West gig was Big Brother's last concert with Joplin, the band—with Joplin still as lead vocalist—toured the U.S. that fall. Reflecting Joplin's crossover appeal, two October 1968 performances at a roller rink in Alexandria, Virginia, were reviewed by John Segraves of the conservative Washington Evening Star at a time when the Washington metropolitan area's hard rock scene was in its infancy.[53] An opera buff at the time,[54] he wrote, "Miss Joplin, in her early 20s, has been for the last year or two the vocalist with Big Brother and the Holding Company, a rock quintet of superior electric expertise. Shortly she will be merely Janis Joplin, a vocalist singing folk rock on her first album as a single. Whatever she does and whatever she sings she'll do it well because her vocal talents are boundless. This is the way she came across in a huge, high-ceilinged roller skating rink without any acoustics but, thankfully a good enough sound system behind her. In a proper room, I would imagine there would be no adjectives to describe her."[53]

Later that month (October 1968), Big Brother performed at the University of Massachusetts Amherst[49] and at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute.[49] Aside from two 1970 reunions, Joplin's last performance with Big Brother was at a Chet Helms benefit in San Francisco on December 1, 1968.[13][16]

1969–1970: Solo career

After splitting from Big Brother and the Holding Company, Joplin formed a new backup group, the Kozmic Blues Band, composed of session musicians like keyboardist Stephen Ryder and saxophonist Cornelius "Snooky" Flowers, as well as former Big Brother and the Holding Company guitarist Sam Andrew and future Full Tilt Boogie Band bassist Brad Campbell. The band was influenced by the Stax-Volt rhythm and blues (R&B) and soul bands of the 1960s, as exemplified by Otis Redding and the Bar-Kays.[13][16][23] The Stax-Volt R&B sound was typified by the use of horns and had a funky, pop-oriented sound in contrast to many of the psychedelic/hard rock bands of the period.

By early 1969, Joplin was allegedly shooting at least $200 worth of heroin per day (equivalent to $1300 in 2016 dollars)[22] although efforts were made to keep her clean during the recording of I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama!. Gabriel Mekler, who produced Kozmic Blues, told publicist-turned-biographer Myra Friedman after Joplin's death that she had lived in his Los Angeles house during the June 1969 recording sessions at his insistence so he could keep her away from drugs and her drug-using friends.[23]

Joplin's appearances with the Kozmic Blues Band in Europe were released in cinemas, in multiple documentaries. Janis, which was reviewed by the Washington Post on March 21, 1975,[55] shows Joplin arriving in Frankfurt by plane and waiting inside a bus next to the Frankfurt venue, while an American female fan who is visiting Germany expresses enthusiasm to the camera (no security was used in Frankfurt, so by the end of the concert, the stage was so packed with people the band members could not see each other). Janis also includes interviews with Joplin in Stockholm and from her visit to London, for her gig at Royal Albert Hall. The London interview was dubbed with a voiceover in the German language for broadcast on German television. John Byrne Cooke, road manager for Joplin and the Kozmic Blues Band, wrote a book published in 2014 in which he revealed the illegal status of Joplin's ongoing use of narcotics.[56]

On Kozmic Blues' tour of Europe, Janis was terrified at every border crossing and customs inspection, knowing that the works and the smack she had stashed on her person could send her directly to jail on a tough rap to beat in foreign courts. But she was unwilling to go without, so she carried a supply everywhere, despite the risks.[56]

On the episode of The Dick Cavett Show that was telecast in the United States on the night of July 18, 1969, Joplin and her band performed "Try (Just a Little Bit Harder)" as well as "To Love Somebody". As Dick Cavett interviewed Joplin, she admitted that she had a terrible time touring in Europe, claiming that audiences there are very uptight and don't "get down".

Released in September 1969, the Kozmic Blues album was certified gold later that year but did not match the success of Cheap Thrills.[51] Reviews of the new group were mixed. However, the album's recording quality and engineering, as well as the musicianship (including three performances by former Bob Dylan/Paul Butterfield/Electric Flag guitarist Mike Bloomfield), were considered superior to her previous releases, and some music critics argued that the band was working in a much more constructive way to support Joplin's sensational vocal talents. Joplin wanted a horn section similar to that featured by the Chicago Transit Authority; her voice had the dynamic qualities and range not to be overpowered by the brighter horn sound.

Some music critics, however, including Ralph J. Gleason of the San Francisco Chronicle, were negative. Gleason wrote that the new band was a "drag" and Joplin should "scrap" her new band and "go right back to being a member of Big Brother ... (if they'll have her)."[13]

Other reviewers, such as reporter Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post, generally ignored the band's flaws and devoted entire articles to celebrating the singer's magic.[57] Bernstein's review said that Joplin "has finally assembled a group of first-rate musicians with whom she is totally at ease and whose abilities complement the incredible range of her voice."[58]

When Joplin and her back-up band performed at Vets Memorial Auditorium in Columbus, Ohio, on Sunday night, May 11, 1969, Columbus Dispatch reviewer John Huddy wrote:

Frequently suggestive with a series of limited but obvious moves, Miss Joplin wears hip-hugging silk bellbottoms and alternates between a wail and a teeth-rattling scream. Like Elvis in his pelvis-moving days or Wayne Cochran with his towering hairdo, Janis is a curiosity as well as a musical attraction. She cultivates a Madame of Rock image, lounging against an organ, exchanging profanities with bandsmen, cackling coarsely at private jokes, even taking a belt or two while onstage. She also has something to say in her songs, about the raw and rudimentary dimensions of sex, love, and life. She gets her point across, splitting a few eardrums in the process. Opening the Joplin concert were Teegarden and Van Winkle, an organ-drums duo ... Before her concert, Miss Joplin walked into the lobby and watched customers (sic) arrive. She was not recognized.[59]

Columbia Records released "Kozmic Blues" as a single, which peaked at number 41 on the Billboard Hot 100, and a live rendition of "Raise Your Hand" was released in Germany and became a top ten hit there. Containing other hits like "Try (Just a Little Bit Harder)", "To Love Somebody", and "Little Girl Blue", I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama! reached number five on the Billboard 200 soon after its release.[60]

Joplin appeared at Woodstock starting at approximately 2:00 a.m., on Sunday, August 17, 1969. Joplin informed her band that they would be performing at the concert as if it were just another gig. On Saturday afternoon, when she and the band were flown by helicopter with the pregnant Joan Baez and Baez's mother from a nearby motel to the festival site and Joplin saw the enormous crowd, she instantly became extremely nervous and giddy. Upon landing and getting off the helicopter, Joplin was approached by reporters asking her questions. She referred them to her friend and sometime lover Peggy Caserta as she was too excited to speak. Initially, Joplin was eager to get on the stage and perform but was repeatedly delayed as bands were contractually obliged to perform ahead of Joplin. Faced with a ten-hour wait after arriving at the backstage area, Joplin shot heroin and drank alcohol[16][22] with Caserta, and by the time of reaching the stage, Joplin was "three sheets to the wind".[13] During her performance, Joplin's voice became slightly hoarse and wheezy, and she struggled to dance.

Joplin pulled through, however, and engaged frequently with the crowd, asking them if they had everything they needed and if they were staying stoned. The audience cheered for an encore, to which Joplin replied and sang "Ball and Chain". Pete Townshend, who performed with the Who later in the same morning after Joplin finished, witnessed her performance and said the following in his 2012 memoir: "She had been amazing at Monterey, but tonight she wasn't at her best, due, probably, to the long delay, and probably, too, to the amount of booze and heroin she'd consumed while she waited. But even Janis on an off-night was incredible."[61]

Janis remained at Woodstock for the remainder of the festival. Starting at approximately 3:00 a.m. on Monday, August 18, Joplin was among many Woodstock performers who stood in a circle behind Crosby, Stills & Nash during their performance, which was the first time anyone at Woodstock ever had heard the group perform.[62] This information was published by David Crosby in 1988.[62] Later in the morning of August 18, Joplin and Joan Baez sat in Joe Cocker's van and witnessed Hendrix's close-of-show performance, according to Baez's memoir And a Voice to Sing With (1989).[63]

Still photographs in color show Joplin backstage with Grace Slick the day after Joplin's performance, wherein Joplin appears to be very happy. Joplin was ultimately unhappy with her performance, however, and blamed Caserta. Her singing was not included (by her own insistence) in the 1970 documentary film or the soundtrack for Woodstock: Music from the Original Soundtrack and More, although the 25th anniversary director's cut of Woodstock includes her performance of "Work Me, Lord". The documentary film of the festival that was released to theaters in 1970 includes, on the left side of a split screen, 37 seconds of footage of Joplin and Caserta walking toward Joplin's dressing room tent.[64]

In addition to Woodstock, Joplin also had problems at Madison Square Garden, in 1969. Biographer Myra Friedman said she witnessed a duet Joplin sang with Tina Turner during the Rolling Stones concert at the Garden on Thanksgiving Day. Friedman said Joplin was "so drunk, so stoned, so out of control, that she could have been an institutionalized psychotic rent by mania."[23] During another Garden concert where she had solo billing on December 19, some observers believed Joplin tried to incite the audience to riot.[23] For part of this concert she was joined onstage by Johnny Winter and Paul Butterfield.

Joplin told rock journalist David Dalton that Garden audiences watched and listened to "every note [she sang] with 'Is she gonna make it?' in their eyes."[29] In her interview with Dalton she added that she felt most comfortable performing at small, cheap venues in San Francisco that were associated with the counterculture.

At the time of this June 1970 interview, she had already performed in the Bay Area for what turned out to be the last time. Sam Andrew, the lead guitarist who had left Big Brother with Joplin in December 1968 to form her back-up band, quit in late summer 1969 and returned to Big Brother. At the end of the year, the Kozmic Blues Band broke up. Their final gig with Joplin was the one at Madison Square Garden with Winter and Butterfield.[13][29]

In February 1970, Joplin traveled to Brazil, where she stopped her drug and alcohol use. She was accompanied on vacation there by her friend Linda Gravenites, who had designed the singer's stage costumes from 1967 to 1969.

In Brazil, Joplin was romanced by a fellow American tourist named David (George) Niehaus, who was traveling around the world. A Joplin biography written by her sister Laura said, "David was an upper-middle-class Cincinnati kid who had studied communications at Notre Dame. ... [and] had joined the Peace Corps after college and worked in a small village in Turkey. ... He tried law school, but when he met Janis he was taking time off."[33]

Niehaus and Joplin were photographed by the press at Rio Carnival in Rio de Janeiro.[29] Gravenites also took color photographs of the two during their Brazilian vacation. According to Joplin biographer Ellis Amburn, in Gravenites' snapshots they "look like a carefree, happy, healthy young couple having a tremendously good time."[16]

Rolling Stone magazine interviewed Joplin during an international phone call, quoting her: "I'm going into the jungle with a big bear of a beatnik named David Niehaus. I finally remembered I don't have to be on stage twelve months a year. I've decided to go and dig some other jungles for a couple of weeks."[16] Amburn added in 1992, "Janis was trying to kick heroin in Brazil, and one of the nicest things about David was that he wasn't into drugs."[16]

When Joplin returned to the U.S., she began using heroin again. Her relationship with Niehaus soon ended because he witnessed her shooting drugs at her new home in Larkspur, California. The relationship was also complicated by her ongoing romantic relationship with Peggy Caserta, who also was an intravenous addict, and Joplin's refusal to take some time off and travel the world with him.[16][65]

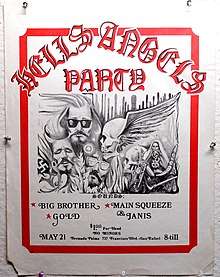

Around this time, she formed her new band, known for a short time as Main Squeeze, then renamed the Full Tilt Boogie Band.[13][16][23] The band comprised mostly young Canadian musicians previously associated with Ronnie Hawkins and featured an organ, but no horn section. Joplin took a more active role in putting together the Full Tilt Boogie band than she did with her prior group. She was quoted as saying, "It's my band. Finally it's my band!"[13] In May 1970, after performing under the name Main Squeeze at a Hell's Angels event, the renamed Full Tilt Boogie Band began a nationwide tour. Joplin became very happy with her new group, which eventually received mostly positive feedback from both her fans and the critics.[13]

Prior to beginning a summer tour with Full Tilt Boogie, she performed in a reunion with Big Brother at the Fillmore West, in San Francisco, on April 4, 1970. Recordings from this concert were included in an in-concert album released posthumously in 1972. She again appeared with Big Brother on April 12 at Winterland, where she and Big Brother were reported to be in excellent form.[16] She performed with the band, billed as Main Squeeze, at a party for the Hells Angels at a venue in San Rafael, California on May 21, 1970, according to a web site maintained by Big Brother guitarist Sam Andrew.[66] Andrew's web site quotes him as saying, "This will be the first time that Janis' old band and her new band will be at the same venue, so everyone is a little on edge."[66]

According to Joplin's biographer Ellis Amburn, Big Brother with its lead singer Nick Gravenites was the opening act at the party that was attended by 2,300 people.[16] The Hells Angels, who had known Joplin since 1966, paid her a fee of 240 dollars to perform.[16] Gravenites and Sam Andrew (who had resumed playing guitar with Big Brother) differed in their opinions of her performance and how substance abuse affected it.[16] Gravenites described her singing as "stupendous," according to Amburn.[16] Amburn quoted Andrew twenty years later: "She was visibly deteriorating and she looked bloated. She was like a parody of what she was at her best. I put it down to her drinking too much and I felt a tinge of fear for her well-being. Her singing was real flabby, no edge at all."[16]

Shortly thereafter, Joplin began wearing multi-coloured feather boas in her hair. (She had not worn them at the May 21 Hell's Angels party / concert in San Rafael).[66] By the time she began touring with Full Tilt Boogie, Joplin told people she was drug-free, but her drinking increased.[16]

Preparing to board the all-star Festival Express train tour through Canada, members of Full Tilt Boogie passed through customs at what was then called Toronto International Airport. Road manager John Byrne Cooke recalled the scene in his 2014 book.[56]

The inspecting officers pass [band members except Joplin] through with a few perfunctory pokes in their bags while a diminutive officer with a solemn, round face begins a thorough search of Janis's luggage. Unaccountably, she seems to welcome his attention.

Her suitcase looks as if she packed by throwing clothes at it from across the room. Her hippie handbag is overflowing with odds and ends scooped up at the last minute during the bleary rush of our early-morning departure [from a hotel in Schenectady, New York where they performed the previous night].

"Hey, man," Janis says to the small customs officer. "Don't you want to look in here? That's my toilet kit, man, there might be some pills in there."

What the hell is going on? I try to signal Janis to quit goading the inspector so we can get out of here before we all keel over from exhaustion. I'm afraid to do it too openly for fear of arousing more suspicion. Janis takes no notice.

Like a sheep being led to the dipping trough, the officer follows Janis's direction. He heads straight for the toilet kit and pulls out a bag of powder. My heart skips a beat.

"What is this, 'ma'mselle'?"

Janis can scarcely contain herself. "That's douche powder, honey!" she proclaims, loud enough for everyone to hear.

"Ah, 'oui, oui, ma'mselle'." The little French-Canadian inspector almost chokes with embarrassment. His complexion explores the scarlet end of the spectrum while he moves on quickly to something safer. But he keeps searching. ...

The border watchdogs can search all day and never find a thing. Janis is clean. She is as respectable as a symphony conductor. She is proud and she is celebrating.

The boys [Full Tilt Boogie musicians] amuse themselves as best they can. [Pianist] Richard Bell passes the time with a yo-yo. Nothing fancy, just up and down, up and down, grinning as he watches Janis urge the inspector on. ...

Janis prolongs the game until even the obtuse little customs inspector finally realizes that no one who has anything to hide would behave like this.[56]

From June 28 to July 4, 1970, during the Festival Express tour, Joplin and Full Tilt Boogie performed alongside Buddy Guy, the Band, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Ten Years After, Grateful Dead, Delaney & Bonnie, Eric Andersen, and Ian & Sylvia.[16] They played concerts in Toronto, Winnipeg, and Calgary.[16][29] Joplin jammed with the other performers on the train, and her performances on this tour are considered to be among her greatest.

Joplin headlined the festival on all three nights. At the last stop in Calgary, she took to the stage with Jerry Garcia while her band was tuning up. Film footage shows her telling the audience how great the tour was and she and Garcia presenting the organizers with a case of tequila. She then burst into a two-hour set, starting with "Tell Mama". Throughout this performance, Joplin engaged in several banters about her love life. In one, she reminisced about living in a San Francisco apartment and competing with a female neighbor in flirting with men on the street. She finished the Calgary concert with long versions of "Get It While You Can" and "Ball and Chain".

Footage of her performance of "Tell Mama" in Calgary became an MTV video in the early 1980s, and the audio from the same film footage was included on the Farewell Song (1982) album. The audio of other Festival Express performances was included on Joplin's In Concert (1972) album. Video of the performances was also included on the Festival Express DVD.

These performances of entire songs during the Festival Express concerts in Toronto and Calgary can be purchased, although other songs remain in vaults and have yet to be released.

In the "Tell Mama" video shown on MTV in the 1980s, Joplin wore a psychedelically colored, loose-fitting costume and feathers in her hair. This was her standard stage costume in the spring and summer of 1970. She chose the new costumes after her friend and designer, Linda Gravenites (whom Joplin had praised in Vogue's profile of her in its May 1968 edition), cut ties with Joplin shortly after their return from Brazil, due largely to Joplin's continued use of heroin.[13][16]

During the Festival Express tour, Joplin was accompanied by Rolling Stone writer David Dalton, who later wrote several articles and two books on Joplin. She told Dalton:

I'm a victim of my own insides. There was a time when I wanted to know everything ... It used to make me very unhappy, all that feeling. I just didn't know what to do with it. But now I've learned to make that feeling work for me. I'm full of emotion and I want a release, and if you're on stage and if it's really working and you've got the audience with you, it's a oneness you feel.[29]

Among Joplin's last public appearances were two broadcasts of The Dick Cavett Show. In her June 25, 1970 appearance, she announced that she would attend her ten-year high school class reunion. When asked if she had been popular in school, she admitted that when in high school, her schoolmates "laughed me out of class, out of town and out of the state"[67] (during the year she had spent at the University of Texas at Austin, Joplin had been voted "Ugliest Man on Campus" by frat boys).[68] In the subsequent Cavett Show broadcast, on August 3, 1970, and featuring Gloria Swanson, Joplin discussed her upcoming performance at the Festival for Peace to be held at Shea Stadium in Queens, New York, three days later.

On August 7, 1970, a tombstone—jointly paid for by Joplin and Juanita Green, who as a child had done housework for Bessie Smith—was erected at Smith's previously unmarked grave. The following day, the Associated Press circulated this news, and the August 9 edition of The New York Times carried it.[69] The lead paragraph of the AP story said Joplin and Green had "shared the cost of a stone for the 'Empress of the Blues,'" but, according to publicist/biographer Myra Friedman, the two women never met.[23] Joplin had been at home in Larkspur, California when she had received a long-distance phone call with an explanation of the need to finance a gravestone for Bessie Smith, whom Joplin had frequently cited as a musical influence.[23] Joplin immediately wrote a check and mailed it to the name and address provided by the phone caller.[23]

On August 8, 1970, as the Associated Press circulated the news about Smith's new gravestone, Joplin performed at the Capitol Theatre (Port Chester, New York). It was there that she first performed "Mercedes Benz", a song (partially inspired by a Michael McClure poem) that she had written that day in the bar next door to the Capitol Theatre with fellow musician and friend Bob Neuwirth.[70] According to Myra Friedman's account,[23] Joplin performed two shows at the Capitol Theatre, the first of which was attended by actors Geraldine Page and her husband Rip Torn,[23] and it was during subsequent free time at a "gin mill" very close to this concert venue that Joplin and Neuwirth penned the lyrics to the song[23] and she performed it at the second show.[23]

Joplin's last public performance with the Full Tilt Boogie Band took place on August 12, 1970, at the Harvard Stadium in Boston. The Harvard Crimson gave the performance a positive, front-page review, despite the fact that Full Tilt Boogie had performed with makeshift amplifiers after their regular sound equipment was stolen in Boston.[23]

Joplin attended her high school reunion on August 14, accompanied by Neuwirth, road manager John Cooke, and sister Laura, but it was reportedly an unhappy experience for her.[71] Joplin held a press conference in Port Arthur during her reunion visit. When asked by a reporter if she ever entertained at Thomas Jefferson High School when she was a student there, Joplin replied, "Only when I walked down the aisles."[13][15] Joplin denigrated Port Arthur and the classmates who had humiliated her a decade earlier.[13]

During late August, September, and early October 1970, Joplin and her band rehearsed and recorded a new album in Los Angeles with producer Paul A. Rothchild, best known for his lengthy relationship with The Doors. Although Joplin died before all the tracks were fully completed, there was enough usable material to compile an LP.

The posthumous Pearl (1971) became the biggest-selling album of her career[51] and featured her biggest hit single, a cover of Kris Kristofferson and Fred Foster's "Me and Bobby McGee" (Kristofferson had previously been Joplin's lover in the spring of 1970).[72] The opening track, "Move Over", was written by Joplin, reflecting the way that she felt men treated women in relationships. Also included was the social commentary of "Mercedes Benz", presented in an a cappella arrangement; the track on the album features the first and only take that Joplin recorded. A cover of Nick Gravenites's "Buried Alive in the Blues", to which Joplin had been scheduled to add her vocals on the day she was found dead, was included as an instrumental.

Joplin checked into the Landmark Motor Hotel in Hollywood on August 24, 1970,[73] near Sunset Sound Recorders,[16] where she began rehearsing and recording her album. During the sessions, Joplin continued a relationship with Seth Morgan, a 21-year-old UC Berkeley student, cocaine dealer, and future novelist who had visited her new home in Larkspur in July and August.[13][16][22] She and Morgan were engaged to be married in early September,[15] even though he visited Sunset Sound Recorders for just eight of Joplin's many rehearsals and sessions.[16]

Morgan later told biographer Myra Friedman that, as a non-musician, he had felt excluded whenever he had visited Sunset Sound Recorders.[23] Instead, he stayed at Joplin's Larkspur home while she stayed alone at the Landmark,[23] although several times she visited Larkspur to be with him and to check the progress of renovations she was having done on the house. She told her construction crew to design a carport to be shaped like a flying saucer, according to biographer Ellis Amburn, the concrete foundation for which was poured the day before she died.[16]

Peggy Caserta claimed in her book, Going Down With Janis (1973), that she and Joplin had decided mutually in April 1970 to stay away from each other to avoid enabling each other's drug use.[22] Caserta, a former Delta Air Lines stewardess[22] and owner of one of the first clothing boutiques in the Haight Ashbury,[22] said in the book that by September 1970, she was smuggling cannabis throughout California[22] and had checked into the Landmark Motor Hotel because it attracted drug users.[22]

For approximately the first two weeks of Joplin's stay at the Landmark, she did not know Caserta was in Los Angeles.[22] Joplin learned of Caserta's presence at the Landmark from a heroin dealer who made deliveries there.[22] Joplin begged Caserta for heroin,[22] and when Caserta refused to provide it, Joplin reportedly admonished her by saying, "Don't think if you can get it, I can't get it."[22] Joplin's publicist Myra Friedman was unaware during Joplin's lifetime that this had happened. Later, while Friedman was working on her book Buried Alive, she determined that the time frame of the Joplin-Caserta encounter was one week before Jimi Hendrix's death.[23]

Within a few days, Joplin became a regular customer of the same heroin dealer who had been supplying Caserta.[22]

Joplin's manager Albert Grossman and his assistant/publicist Friedman, had staged an intervention with Joplin the previous winter while Joplin was in New York.[23] In September 1970, Grossman and Friedman, who worked out of a New York office, knew Joplin was staying at a Los Angeles hotel, but were unaware it was a haven for drug users and dealers.[23]

Grossman and Friedman knew during Joplin's lifetime that her friend Caserta, whom Friedman met during the New York sessions for Cheap Thrills[22] and on later occasions, used heroin.[23] During the many long-distance telephone conversations that Joplin and Friedman had in September 1970 and on October 1, Joplin never mentioned Caserta, and Friedman assumed Caserta had been out of Joplin's life for a while.[23] Friedman, who had more time than Grossman to monitor the situation, never visited California.[23] She thought Joplin sounded on the phone like she was less depressed than she had been over the summer.[23]

When Joplin was not at Sunset Sound Recorders, she liked to drive her Porsche over the speed limit "on the winding part of Sunset Blvd.", according to a statement made by her attorney Robert Gordon in 1995 at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony.[74] Friedman wrote that the only Full Tilt Boogie member who rode as her passenger, Ken Pearson, often hesitated to join her,[23] though he did on the night she died.[23] He was not interested in experimenting with hard drugs.[23]

On September 26, 1970, Joplin recorded vocals for "Half Moon" and "Cry Baby".[75] The session ended with Joplin, organist Ken Pearson, and drummer Clark Pierson making a special one-minute recording as a birthday gift to John Lennon.[75] Joplin was among several singers who had been contacted by Yoko Ono with a request for a taped greeting for Lennon's 30th birthday,[76] on October 9. Joplin, Pearson, and Pierson chose the Dale Evans composition "Happy Trails" as part of the greeting. Lennon told Dick Cavett on-camera the following year that Joplin's recorded birthday wishes arrived at his home after her death.[76]

The last recording Joplin completed was on October 1, 1970—"Mercedes Benz". On Saturday, October 3, Joplin visited Sunset Sound Recorders[16] to listen to the instrumental track for Nick Gravenites's song "Buried Alive in the Blues", which the band had recorded earlier that day.[56] She and Paul Rothchild agreed she would record the vocal the following day.[29][33][56]

At some point on Saturday, she learned by telephone, to her dismay, that Seth Morgan had met other women at a Marin County, California, restaurant, invited them to her home, and was shooting pool with them using her pool table.[23] People at Sunset Sound Recorders overheard Joplin expressing anger about the state of her relationship with Morgan,[23] as well as joy about the progress of the sessions.[23] As biographer Myra Friedman wrote based on early 1970s interviews with some of the people present at Sunset Sound Recorders,[23]

What impressed everyone that night when she arrived at the studio was the exceptional brightness of her spirits.

"You're smiling and jumping around, Janis," [pianist] Richard Bell remarked as he and Janis walked toward a Chinese restaurant during a break.

"Well," she teased, "I've got a secret." [When Friedman wrote this text in the early 1970s, her sources included a list of outgoing phone calls that the Landmark Motor Hotel claimed Joplin had made from her room, allegedly including one to Los Angeles City Hall to inquire about a marriage license for her and Seth Morgan. Friedman believed the "secret" was marriage plans for Joplin and Morgan. In a version of Friedman's book that she wrote twenty years later, she said about the hotel's claim of a phone call to City Hall, "This may have been untrue."][23]

By the time they returned to the studio, it was jammed. Nick Gravenites was there. So was song writer Bobby Womack. Bennett Glotzer [Albert Grossman's partner in their New York-based talent management company] was around. All in all, there were perhaps twenty to twenty-five people present. Janis did not sing that night, but merely listened to the instrumental track the band had completed that day. It was Nick's song, "Buried Alive in the Blues."

Janis was exhilarated by the prospect of doing the vocal on Sunday, a light like a sunburst in her smile and eyes.[23]

Joplin and Ken Pearson later left the studio together and she drove him and a male fan in her Porsche[23] to the West Hollywood landmark called Barney's Beanery. Friedman wrote, "At the bar, she drank vodka and orange juice, only two."[23] Glotzer was also present there, according to what he told John Byrne Cooke immediately after he (Glotzer) learned of her death.[56] After midnight, she drove Pearson and the male fan back to the Landmark.[23] During the car ride, the fan asked Joplin questions "about her singing style," according to Friedman,[23] and "she mostly ignored him" so she could converse with Pearson.[23] As Joplin and Pearson prepared to part in the lobby of the Landmark, she expressed a fear, possibly in jest, that he and the other Full Tilt Boogie musicians might decide to stop making music with her.[23]. Pearson was the second-to-last person to see her alive. The last was the Landmark's night shift desk clerk. He had met her several times but did not know her.

Personal life

Joplin's significant relationships with men included ones with Peter de Blanc,[23][30][31][32][33] Country Joe McDonald (who wrote the song "Janis" at Joplin's request),[77] David (George) Niehaus,[16][29][33][65] Kris Kristofferson,[16][23] and Seth Morgan (from July 1970 until her death, at which time they were allegedly engaged).[78][79]

She also had relationships with women. During her first stint in San Francisco in 1963, Joplin met and briefly lived with Jae Whitaker, an African American woman whom she had met while playing pool at the bar Gino & Carlo in North Beach. Whitaker broke off their relationship because of Joplin's hard drug use and sexual relationships with other people.[80] Whitaker was first identified by name in connection with Joplin in 1999, when Alice Echols' biography Scars of Sweet Paradise was published.[13]

Joplin also had an on-again-off-again romantic relationship with Peggy Caserta.[16][65][81] They first met in November 1966 when Big Brother performed at a San Francisco venue called The Matrix. Caserta was one of 15 people in the audience.[22] At the time, Caserta ran a successful clothing boutique in the Haight Ashbury. Approximately a month after Caserta attended the concert, Joplin visited her boutique and said she could not afford to buy a pair of jeans that was for sale.[22] Caserta took pity on her and gave her a pair for free.[22] Their friendship was platonic for more than a year.[22] Before it moved to the next level, Caserta was in love with Big Brother guitarist Sam Andrew, and sometime during the first half of 1968 she traveled from San Francisco to New York to flirt with him.[22] He did not want a serious relationship with her, and Joplin sympathized with Caserta's disappointment.[22]

The Woodstock movie includes 37 seconds of Joplin and Caserta walking together before they reached the tent where Joplin waited for her turn to perform. By the time the festival took place in August 1969, both women were intravenous heroin addicts.

According to Caserta's book Going Down With Janis, Joplin introduced her to Seth Morgan in Joplin's room at the Landmark Motor Hotel on Tuesday evening, September 29, 1970.[22] Caserta "had seen him around" San Francisco but had not met him before.[22] All three of them agreed to reunite three nights later, on Friday night, for a ménage à trois in Joplin's room.[22] Caserta saw Joplin briefly the next day, Wednesday, again in Joplin's room, when Caserta accommodated her new Los Angeles friend Debbie Nuciforo, age 19,[82] an aspiring hard rock drummer who wanted to meet Joplin.[22] Nuciforo was stoned on heroin at the time, and the three women's encounter was brief and unpleasant.[22] Caserta suspected that the reason for Joplin's foul mood was that Morgan had abandoned her earlier that day after having spent less than 24 hours with her.[22]

Caserta did not see nor communicate by phone with Joplin again, although she later claimed she had made several attempts to reach her by phone at the Landmark Motor Hotel and at Sunset Sound Recorders. Caserta and Seth Morgan lost touch with each other, and each decided independently to abandon Joplin on Friday night, October 2.[22] Joplin mentioned her disappointment (over both of her friends' bailing out of their ménage à trois) to her drug dealer on Saturday while he was selling her the dose of heroin that killed her, as Caserta later learned from the drug dealer.[16][22]

Biographer Myra Friedman commented in her original version of Buried Alive (1973):[83]

Given the near-infinite potentials of infancy, it is really impossible to make generalizations about what lies behind sexual practices. This, however, is probable: to become clearly homosexual, to make the choice that one honestly prefers relations with one's own sex, no matter the origins of such preference, requires a certain integration, a stability of psychic development, a tidiness of personality organization. The ridicule and the humiliation that took place at that most delicate period in [Joplin's] early teens, her own inability to surmount the obstacles to regular growth, devastated her a great deal more than most people comprehended. Janis was not heir to an ego so cohesive as to permit her an identity one way or the other. She was, as [the psychiatric social worker she saw regularly in Beaumont, Texas in 1965 and 1966] Mr. [Bernard] Giarritano put it [in an interview with Friedman], "diffused" -- spewing, splattering, splaying all over, without a center to hold. That had as much to do with her original use of drugs [before she first met Giarritano] as did the critical component of guilt and its multiplicity of sources above and beyond the contribution made by her relationships with women. Were she so simple as the lesbians wished her to be or so free as her associates imagined![23]

Kim France reported in The New York Times article, "Nothin' Left to Lose" (May 2, 1999): "Once she became famous, Joplin cursed like a truck driver, did not believe in wearing undergarments, was rarely seen without her bottle of Southern Comfort and delighted in playing the role of sexual predator."[84]

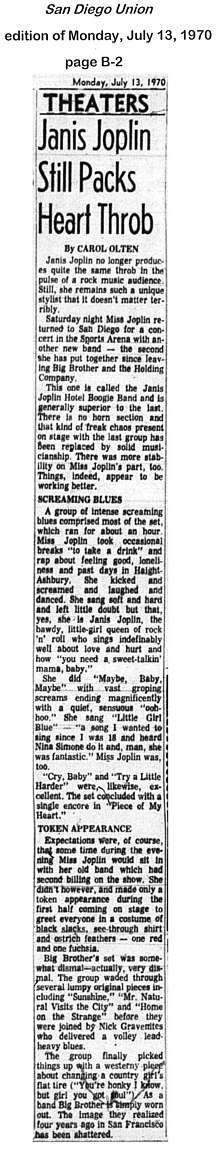

On July 11, 1970, Full Tilt Boogie and Big Brother and the Holding Company both performed at the same concert in the San Diego Sports Arena,[85] which was decades later renamed the Valley View Casino Center. Joplin sang with Full Tilt Boogie and appeared briefly onstage with Big Brother without singing, according to the next day's review in the San Diego Union. She had a conversation offstage with her old friend Richard Hundgen, the Grateful Dead's San Francisco-based road manager whom she had known since 1966, in which she said:

I hear a rumor that somebody in San Francisco is spreading stories that I'm a dyke. You go back there and find out who it is and tell them that Janis says she's gotten it on with a couple of thousand cats in her life and a few hundred chicks and see what they can do with that![23]

Death

In the late afternoon of Sunday, October 4, 1970, producer Paul Rothchild became concerned when Joplin failed to show up at Sunset Sound Recorders for a recording session in which she was scheduled to provide the vocal track for the instrumental track of the song "Buried Alive in the Blues". In the evening, Rothchild phoned the Landmark Motor Hotel and reached Full Tilt Boogie's road manager, John Cooke, Joplin’s close friend who was staying at the Landmark in a room that was not near hers, according to his 2014 book On the Road with Janis Joplin.[86] Rothchild expressed his concern over her absence from Sunset Sound Recorders and asked Cooke to search for her.[87] Cooke and two of his friends noticed her psychedelically painted Porsche 356 C Cabriolet in the hotel parking lot.[88] Upon entering Joplin's room (#105), he found her dead on the floor beside her bed.[89]

Alcohol was present in the hotel room. Newspapers reported that no drugs or paraphernalia was present.[90][91]. According to a 1983 book authored by Joseph DiMona and Los Angeles County coroner Thomas Noguchi, evidence of narcotics was removed from the scene by a friend of Joplin’s and later put back there after the person realized that an autopsy was going to reveal that narcotics were in her system.[92] The book adds that prior to Joplin’s death, Noguchi had investigated other fatal drug overdoses of decedents in Los Angeles whose friends believed they were doing favors for decedents by removing evidence of narcotics, then they “thought things over” and returned to put back the evidence.[93] Noguchi performed an autopsy on Joplin and determined the cause of death to be a heroin overdose, possibly compounded by alcohol.[23][94] John Cooke believed Joplin had been given heroin that was much more potent than what she and other Los Angeles heroin users had received on previous occasions, as was indicated by overdoses of several of her dealer's other customers during the same weekend as hers.[95][96] Her death was ruled accidental.[97]

According to Joplin’s publicist-turned-biographer Myra Friedman, who researched the cause of death in the early 1970s, when memories of people at the Los Angeles County coroner's office were fresh and all official documents still existed:

"The heroin in her system might have killed her immediately. It did not. When, after a while, she walked out to the lobby [from her room at the Landmark Motor Hotel], she could not have known she was dying. There she chatted with the hotel clerk for a second and asked him to change a five-dollar bill for cigarettes, which she purchased [from the cigarette machine in the lobby].

Alcohol was also present in the blood, and her liver showed the effects of long-term heavy drinking. Additional tests for barbiturates, phenothiazine, amphetamines, Librium, Valium, Noludar, meprobamate, methadone, Soma, Quaalude and codeine were negative. . . .

Much mystery surrounded the fact that Janis had not died immediately. Some people insisted that a heroin overdose could not have happened as it did. The Medical Examiner's Office of New York County [where Friedman lived] informs me that while it is more common for an OD to occur instantly after an injection, a delay until the moment of death is not so strikingly unusual. Clarifying this further, the Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs states that the term "overdose" is most frequently erroneous. The report cites information that those sudden deaths following an injection of heroin are actually the result of an adulteration of the product with various substances or of other mysterious factors: what is called a "synergistic reaction" to a combination of drugs, for example, or of other toxic factors. Death from what is literally an overdose of heroin itself is, in fact, usually slow.[23]

Peggy Caserta, Joplin's close friend, and Seth Morgan, Joplin's fiance, both had failed to meet Joplin the Friday immediately prior to her death, October 2, and Joplin had been expecting both of them to keep her company that night.[22] According to Caserta, Joplin was saddened that neither of her friends visited her at the Landmark as they had promised.[16][22] During the twenty-four hours Joplin lived after this disappointment, Caserta did not phone her to explain why she had failed to show up.[22] Caserta admitted to waiting until late Saturday night to dial the Landmark switchboard, only to learn that Joplin had instructed the desk clerk not to accept any incoming phone calls for her after midnight.[22] Morgan did speak to Joplin via telephone within the twenty-four hours prior to her death, but it is not known whether he admitted to her that he had broken his promise.[16]

Joplin was cremated at Pierce Brothers Westwood Village Memorial Park and Mortuary in Los Angeles, California, and her ashes were scattered from a plane into the Pacific Ocean.[98][99]

Legacy

Joplin's death in October 1970 at age 27 stunned her fans and shocked the music world, especially when coupled with the death just 16 days earlier of another rock icon, Jimi Hendrix, also at age 27. (This would later cause some people to attribute significance to the death of musicians at the age of 27, as celebrated in the notional '27 Club'.) Music historian Tom Moon wrote that Joplin had "a devastatingly original voice", music columnist Jon Pareles of The New York Times wrote that Joplin as an artist was "overpowering and deeply vulnerable", and author Megan Terry said that Joplin was the female version of Elvis Presley in her ability to captivate an audience.[85]

A book about Joplin by her publicist Myra Friedman, titled Buried Alive: The Biography of Janis Joplin (1973),[100] was excerpted in many newspapers. At the same time, Peggy Caserta's memoir, Going Down With Janis (1974),[101] attracted a lot of attention, with its provocative title referring to her performing oral sex with Joplin while they were high on heroin, in September 1970. The very first sentence in the book goes into more detail about that particular encounter. Caserta's language and description repelled many people at a time when few books or filmed interviews of Joplin or her loved ones were accessible to the public. Peggy Caserta was described as "halfway between a groupie and a friend" in an interview that writer Ellis Amburn did with Joplin's bandmate Sam Andrew circa 1990 and published in 1992.[16] Soon after the 1973 publication of Going Down With Janis, Joplin's friends learned that graphic descriptions of sexual acts and intravenous drug use were not the only portions of the book that would haunt them.

According to a statement in the early 1990s by a close friend of Caserta and Joplin's, Caserta's book angered the Los Angeles heroin dealer she described in detail, including the make and model of his car, for her book. According to Ellis Amburn, in 1973 a "carful of dope dealers" visited a Los Angeles lesbian bar Caserta had been frequenting since Joplin was alive.[16] Amburn quoted Caserta's friend Kim Chappell, who was in the alley behind the bar: "I was stabbed because, when Peggy's book came out, her dealer, the same one who'd given Janis her last fix, didn't like it that he was referred to and was out to get Peggy. He couldn't find her, so he went for her lover. When they realized who I was, they felt that my death would also hit Peggy, and so they stabbed me."[16] Despite being "stabbed three times in the chest, puncturing both lungs," Chappell eventually recovered.[16]

According to biographers, Caserta was one of many friends of Joplin's who did not become clean and sober until a very long time after the singer's death, while others died from overdoses.[13][23] Although (Big Brother guitarist) James Gurley's wife, who was Joplin's close friend, died from a heroin overdose in 1969, he did not become clean and sober until 1984.[16] Caserta survived "a near-fatal OD in December 1995," wrote Alice Echols.[13] On January 13, 2000, Caserta appeared on-camera for a segment about Joplin on 20/20.[102]

Joplin, along with Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane, opened opportunities in the rock music business for future female singers.[85]

Joplin's body art, with a wristlet and a small heart on her left breast, by the San Francisco tattoo artist Lyle Tuttle, was an early moment in the popular culture's acceptance of tattoos as art.[103] Another trademark was her flamboyant hair styles, which often included colored streaks, and accessories such as scarves, beads, and feathers. When in New York City, Joplin, often in the company of actor Michael J. Pollard, frequented Limbo on St. Mark's Place. Joplin, well known to the boutique's employees, made a practice of putting aside vintage and other one-of-a-kind garments she favored on stage and off.

The Mamas & the Papas' song "Pearl" (1971), from their People Like Us album, was a tribute. Likewise, Leonard Cohen's song, "Chelsea Hotel #2" (1974), is about Joplin,[104] and lyricist Robert Hunter has commented that Jerry Garcia's "Birdsong" from his first solo album, Garcia (1972), is about Joplin and the end of her suffering through death.[105][106] Mimi Farina's composition, "In the Quiet Morning", most famously covered by Joan Baez on her Come from the Shadows (1972) album, was a tribute to Joplin.[107] Another song by Baez, "Children of the Eighties," mentioned Joplin. A Serge Gainsbourg-penned French language song by English singer Jane Birkin, "Ex fan des sixties" (1978), references Joplin alongside other disappeared "idols" such as Jimi Hendrix, Brian Jones, and Marc Bolan. When Joplin was alive, Country Joe McDonald released a song called "Janis" on his band's album I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die (1967).

At the 1976 Montreux Jazz Festival, Nina Simone, whom Joplin admired greatly, commented on Joplin and referred to the documentary Janis (1975) that evidently was screened at the festival:

You know I made thirty-five albums, they bootlegged seventy. Oh, everybody took a chunk of me. And yesterday I went to see Janis Joplin's film here. And what distressed me the most, and I started to write a song about it, but I decided you weren't worthy. Because I figured that most of you are here for the festival. Anyway the point is it pained me to see how hard she worked. Because she got hooked into a thing, and it wasn't on drugs. She got hooked into a feeling and she played to corpses.

The film The Rose (1979) is loosely based on Joplin's life. Originally planned to be titled Pearl—Joplin's nickname and the title of her last album—the film was fictionalized after her family declined to allow the producers the rights to her story.[108][109] Bette Midler earned a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in the film.

In 1988, on what would have been Joplin's 45th birthday, the Janis Joplin Memorial, with an original gold, multi-image sculpture of Joplin by Douglas Clark, was dedicated during a ceremony in Port Arthur, Texas.[110]

In 1992, the first major biography of Joplin in two decades, Love, Janis, authored by her younger sister, Laura Joplin, was published. In an interview, Laura stated that Joplin enjoyed being on the Dick Cavett Show, that Joplin while growing up in Texas had difficulties with some people at school, but not the entire school, and that Joplin was really enthusiastic after performing at Woodstock in 1969.[111]

In 1995, Joplin was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In 2005, she received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In November 2009, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum honored her as part of its annual American Music Masters Series;[112] among the artifacts at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum exhibition are Joplin's scarf and necklaces, her 1965 Porsche 356 Cabriolet with psychedelically designed painting, and a sheet of LSD blotting paper designed by Robert Crumb, designer of the Cheap Thrills cover.[113] Also in 2009, Joplin was the honoree at the Rock Hall's American Music Master concert and lecture series.[114]

In the late 1990s, the musical play Love, Janis was created and directed by Randal Myler, with input from Janis' younger sister Laura and Big Brother guitarist Sam Andrew, with an aim to take it to Off Broadway. Opening in the summer of 2001 and scheduled for only a few weeks of performances, the show won acclaim, packed houses, and was held over several times.

In 2013, Washington's Arena Stage featured a production of A Night with Janis Joplin, starring Mary Bridget Davies. In it, Joplin puts on a concert for the audience, while telling stories of her past inspirations including Odetta, Aretha Franklin, and others. It went on tour in 2016.[115]

On November 4, 2013, Joplin was awarded with the 2,510th star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her contributions to the music industry. Her star is located at 6752 Hollywood Boulevard, in front of Musicians Institute.[116][117]

On August 8, 2014, the U.S. Postal Service revealed a commemorative stamp honoring Janis Joplin, as part of its Music Icons Forever Stamp series during a first-day-of-issue ceremony at the Outside Lands Music Festival at Golden Gate Park.[118]

On December 15, 2015, Amy J. Berg released her biographical documentary film, Janis: Little Girl Blue, narrated by Cat Power. It was a New York Times Critics' Pick.[119] Among the memorabilia she left behind is a Gibson Hummingbird guitar.[120]

Influence

Joplin had a profound influence on many singers. For example, Florence Welch of Florence and the Machine spoke of Joplin's impact, in an interview for Why Music Matters that appeared in a commercial against piracy:

I learnt about Janis from an anthology of female blues singers. Janis was a fascinating character who bridged the gap between psychedelic blues and soul scenes. She was so vulnerable, self-conscious and full of suffering. She tore herself apart yet on stage she was totally different. She was so unrestrained, so free, so raw and she wasn't afraid to wail. Her connection with the audience was really important. It seems to me the suffering and intensity of her performance go hand in hand. There was always a sense of longing, of searching for something. I think she really sums up the idea that soul is about putting your pain into something beautiful.[121]

Stevie Nicks considers Joplin one of her idols, and has said:

You could say that being yelled at by Janis Joplin was one of the great honors of my life. Early in my career, Lindsey Buckingham and I were in a band called Fritz. There were two gigs we played in San Francisco that changed everything for me - One was opening up for Jimi Hendrix, who was completely magical. The other was the time that we opened up for Janis at the San Jose Fairgrounds, around 1970.

It was a hot summer day, and things didn't start off well because the entire show was running late. That meant our set was running over. We were onstage and going over pretty well, when I turned and saw a furious Janis Joplin on the side of the stage, yelling at us. She was screaming something like, "What the fuck are you assholes doing? Get the hell off of my stage." Actually, she might have even been a little cruder than that — it was hard to hear.

But then Janis got up on that stage with her band, and this woman who was screaming at me only moments before suddenly became my new hero. Janis Joplin was not what anyone would call a great beauty, but she became beautiful because she made such a powerful and deep emotional connection with the audience. I didn't mind the feathers and the bell-bottom pants either. Janis didn't dress like anyone else, and she definitely didn't sing like anyone else.

Janis put herself out there completely, and her voice was not only strong and soulful, it was painfully and beautifully real. She sang in the great tradition of the rhythm & blues singers that were her heroes, but she brought her own dangerous, sexy rock & roll edge to every single song. She really gave you a piece of her heart. And that inspired me to find my own voice and my own style.[122]

Pink said about Joplin: "She was so inspiring by singing blues music when it wasn't culturally acceptable for white women, and she wore her heart on her sleeve. She was so witty and charming and intelligent, but she also battled an ugly-duckling syndrome. I would love to play her in a movie." [123] In a tribute performance on her Try This Tour, Pink called Joplin "a woman who inspired me when everyone else ... didn't!"[124]

Discography

Janis Joplin recorded four albums in her four-year career.[81] The first two albums were recorded with and credited to Big Brother and the Holding Company; the later two were recorded with different backing bands and released as solo albums.[125] Previously unreleased studio and live material, including early performances as well as Joplin's greatest hits, have been released on several posthumous compilations.[126]

- Big Brother and the Holding Company (1967)

- Cheap Thrills (1968)

- I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama! (1969)

- Pearl (1971)

Some of Joplin's live concerts with Big Brother were professionally recorded and have been released on albums like Live at Winterland '68 and Live at the Carousel Ballroom 1968.

Full discography

Big Brother and the Holding Company

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big Brother and the Holding Company | 1967 | Mainstream Records / Columbia | Re-released 1967 by Columbia with two extra tracks |

| Cheap Thrills | 1968 | Columbia | 2x Multi-Platinum Recording Industry Association of America |

| Live at Winterland '68 | 1998 | Columbia Legacy | Posthumous release of live material |

| Live at the Carousel Ballroom 1968 | 2012 | Legacy Recordings | Posthumous release of live material |

Kozmic Blues Band

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama! | 1969 | Columbia | Platinum RIAA |

| The Woodstock Experience | 2009 | Legacy Recordings | Posthumous release of live material |

Full Tilt Boogie Band

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearl | 1971 | Columbia | posthumous, 4x Multi-Platinum RIAA |

Big Brother & the Holding Company / Full Tilt Boogie

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Concert | 1972 | Legacy CK65786 | Posthumous release of live material |

Later collections

| Title | Release date | Label | Notes | Certifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|