Intermediate filament

Intermediate filaments (IFs) are cytoskeletal structural components found in the cells of vertebrates, and many invertebrates.[1][2][3] Homologues of the IF protein have been noted in an invertebrate, the cephalochordate Branchiostoma.[4]

| Intermediate filament tail domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

structure of lamin a/c globular domain | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | IF_tail | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00932 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001322 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00198 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 1ivt / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Intermediate filament rod domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

human vimentin coil 2b fragment (cys2) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Filament | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00038 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR016044 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00198 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 1gk7 / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Intermediate filament head (DNA binding) region | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Filament_head | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF04732 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR006821 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 1gk7 / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Peripherin neuronal intermediate filament protein | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | PRPH |

| Alt. symbols | NEF4 |

| NCBI gene | 5630 |

| HGNC | 9461 |

| OMIM | 170710 |

| RefSeq | NM_006262.3 |

| UniProt | P41219 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 12 q13.12 |

| Nestin neuronal stem cell intermediate filament protein | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | NES |

| NCBI gene | 10763 |

| HGNC | 7756 |

| OMIM | 600915 |

| RefSeq | NP_006608 |

| UniProt | P48681 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 1 q23.1 |

Intermediate filaments are composed of a family of related proteins sharing common structural and sequence features. Initially designated 'intermediate' because their average diameter (10 nm) is between those of narrower microfilaments (actin) and wider myosin filaments found in muscle cells, the diameter of intermediate filaments is now commonly compared to actin microfilaments (7 nm) and microtubules (25 nm).[1][5] Animal intermediate filaments are subcategorized into six types based on similarities in amino acid sequence and protein structure.[6] Most types are cytoplasmic, but one type, Type V is a nuclear lamin. Unlike microtubules, IF distribution in cells show no good correlation with the distribution of either mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum.[7]

Structure

The structure of proteins that form intermediate filaments (IF) was first predicted by computerized analysis of the amino acid sequence of a human epidermal keratin derived from cloned cDNAs.[8] Analysis of a second keratin sequence revealed that the two types of keratins share only about 30% amino acid sequence homology but share similar patterns of secondary structure domains.[9] As suggested by the first model, all IF proteins appear to have a central alpha-helical rod domain that is composed of four alpha-helical segments (named as 1A, 1B, 2A and 2B) separated by three linker regions.[9][10]

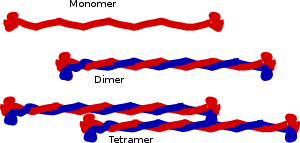

The central building block of an intermediate filament is a pair of two intertwined proteins that is called a coiled-coil structure. This name reflects the fact that the structure of each protein is helical, and the intertwined pair is also a helical structure. Structural analysis of a pair of keratins shows that the two proteins that form the coiled-coil bind by hydrophobic.[11][12] The charged residues in the central domain do not have a major role in the binding of the pair in the central domain.[11]

Cytoplasmic IFs assemble into non-polar unit-length filaments (ULFs). Identical ULFs associate laterally into staggered, antiparallel, soluble tetramers, which associate head-to-tail into protofilaments that pair up laterally into protofibrils, four of which wind together into an intermediate filament.[13] Part of the assembly process includes a compaction step, in which ULF tighten and assume a smaller diameter. The reasons for this compaction are not well understood, and IF are routinely observed to have diameters ranging between 6 and 12 nm.

The N-terminus and the C-terminus of IF proteins are non-alpha-helical regions and show wide variation in their lengths and sequences across IF families. The N-terminal "head domain" binds DNA.[14] Vimentin heads are able to alter nuclear architecture and chromatin distribution, and the liberation of heads by HIV-1 protease may play an important role in HIV-1 associated cytopathogenesis and carcinogenesis.[15] Phosphorylation of the head region can affect filament stability.[16] The head has been shown to interact with the rod domain of the same protein.[17]

C-terminal "tail domain" shows extreme length variation between different IF proteins.[18]

The anti-parallel orientation of tetramers means that, unlike microtubules and microfilaments, which have a plus end and a minus end, IFs lack polarity and cannot serve as basis for cell motility and intracellular transport.

Also, unlike actin or tubulin, intermediate filaments do not contain a binding site for a nucleoside triphosphate.

Cytoplasmic IFs do not undergo treadmilling like microtubules and actin fibers, but are dynamic.[19]

Biomechanical properties

IFs are rather deformable proteins that can be stretched several times their initial length.[20] The key to facilitate this large deformation is due to their hierarchical structure, which facilitates a cascaded activation of deformation mechanisms at different levels of strain.[12] Initially the coupled alpha-helices of unit-length filaments uncoil as they're strained, then as the strain increases they transition into beta-sheets, and finally at increased strain the hydrogen bonds between beta-sheets slip and the ULF monomers slide along each other.[12]

Types

There are about 70 different human genes coding for various intermediate filament proteins. However, different kinds of IFs share basic characteristics: In general, they are all polymers that measure between 9-11 nm in diameter when fully assembled.

Animal IFs are subcategorized into six types based on similarities in amino acid sequence and protein structure:[6]

Types I and II – acidic and basic keratins

These proteins are the most diverse among IFs and constitute type I (acidic) and type II (basic) IF proteins. The many isoforms are divided in two groups:

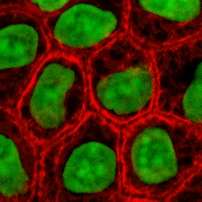

- epithelial keratins (about 20) in epithelial cells (image to right)

- trichocytic keratins (about 13) (hair keratins), which make up hair, nails, horns and reptilian scales.

Regardless of the group, keratins are either acidic or basic. Acidic and basic keratins bind each other to form acidic-basic heterodimers and these heterodimers then associate to make a keratin filament.[6]

Type III

There are four proteins classed as type III IF proteins, which may form homo- or heteropolymeric proteins.

- Desmin IFs are structural components of the sarcomeres in muscle cells.

- GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) is found in astrocytes and other glia.

- Peripherin found in peripheral neurons.

- Vimentin, the most widely distributed of all IF proteins, can be found in fibroblasts, leukocytes, and blood vessel endothelial cells. They support the cellular membranes, keep some organelles in a fixed place within the cytoplasm, and transmit membrane receptor signals to the nucleus.[6]

Type IV

Type V - nuclear lamins

- Lamins

Lamins are fibrous proteins having structural function in the cell nucleus.

In metazoan cells, there are A and B type lamins, which differ in their length and pI. Human cells have three differentially regulated genes. B-type lamins are present in every cell. B type lamins, lamin B1 and B2, are expressed from the LMNB1 and LMNB2 genes on 5q23 and 19q13, respectively. A-type lamins are only expressed following gastrulation. Lamin A and C are the most common A-type lamins and are splice variants of the LMNA gene found at 1q21.

These proteins localize to two regions of the nuclear compartment, the nuclear lamina—a proteinaceous structure layer subjacent to the inner surface of the nuclear envelope and throughout the nucleoplasm in the nucleoplasmic veil.

Comparison of the lamins to vertebrate cytoskeletal IFs shows that lamins have an extra 42 residues (six heptads) within coil 1b. The c-terminal tail domain contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS), an Ig-fold-like domain, and in most cases a carboxy-terminal CaaX box that is isoprenylated and carboxymethylated (lamin C does not have a CAAX box). Lamin A is further processed to remove the last 15 amino acids and its farnesylated cysteine.

During mitosis, lamins are phosphorylated by MPF, which drives the disassembly of the lamina and the nuclear envelope.[6]

Function

Cell adhesion

At the plasma membrane, some keratins interact with desmosomes (cell-cell adhesion) and hemidesmosomes (cell-matrix adhesion) via adapter proteins.

Associated proteins

Filaggrin binds to keratin fibers in epidermal cells. Plectin links vimentin to other vimentin fibers, as well as to microfilaments, microtubules, and myosin II. Kinesin is being researched and is suggested to connect vimentin to tubulin via motor proteins.

Keratin filaments in epithelial cells link to desmosomes (desmosomes connect the cytoskeleton together) through plakoglobin, desmoplakin, desmogleins, and desmocollins; desmin filaments are connected in a similar way in heart muscle cells.

Diseases arising from mutations in IF genes

- Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM), mutations in the DES gene.[22][23]

- Epidermolysis bullosa simplex; keratin 5 or keratin 14 mutation

- Laminopathies are a family of diseases caused by mutations in nuclear lamins and include Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome and various lipodystrophies and cardiomyopathies among others.

In other organisms

IF proteins are universal among animals in the form of a nuclear lamin. The Hydra has an additional "nematocilin" derived from the lamin. Cytoplasmic IFs (type I-IV) found in humans are widespread in Bilateria; they also arose from a gene duplication event involving "type V" nuclear lamin. In addition, a few other diverse types of Eukaryotes have lamins, suggesting an early origin of the protein.[21]

There was not really a concrete definition of an "intermediate filament protein", in the sense that the size or shape-based definition does not cover a monophyletic group. With the inclusion of unusual proteins like the network-forming beaded lamins (type VI), the current classification is moving to a clade containing nuclear lamin and its many descendents, characterized by sequence similarity as well as the exon structure. Functionally-similar proteins out of this clade, like crescentins, alveolins, tetrins, and epiplasmins, are therefore only "IF-like". They likely arose through convergent evolution.[21]

References

- Herrmann H, Bär H, Kreplak L, Strelkov SV, Aebi U (July 2007). "Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 8 (7): 562–73. doi:10.1038/nrm2197. PMID 17551517.

- Chang L, Goldman RD (August 2004). "Intermediate filaments mediate cytoskeletal crosstalk". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 5 (8): 601–13. doi:10.1038/nrm1438. PMID 15366704.

- Traub, P. (2012), Intermediate Filaments: A Review, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, p. 33, ISBN 9783642702303CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Karabinos A, Riemer D, Erber A, Weber K (October 1998). "Homologues of vertebrate type I, II and III intermediate filament (IF) proteins in an invertebrate: the IF multigene family of the cephalochordate Branchiostoma". FEBS Letters. 437 (1–2): 15–8. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01190-9. PMID 9804163.

- Ishikawa H, Bischoff R, Holtzer H (September 1968). "Mitosis and intermediate-sized filaments in developing skeletal muscle". J. Cell Biol. 38 (3): 538–55. doi:10.1083/jcb.38.3.538. PMC 2108373. PMID 5664223.

- Szeverenyi I, Cassidy AJ, Chung CW, Lee BT, Common JE, Ogg SC, Chen H, Sim SY, Goh WL, Ng KW, Simpson JA, Chee LL, Eng GH, Li B, Lunny DP, Chuon D, Venkatesh A, Khoo KH, McLean WH, Lim YP, Lane EB. "Human Intermediate Filament Database". PMID 18033728.

- Soltys, BJ and Gupta RS: Interrelationships of endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, intermediate filaments, and microtubules-a quadruple fluorescence labeling study. Biochem. Cell. Biol. (1992) 70: 1174-1186

- Hanukoglu I, Fuchs E (November 1982). "The cDNA sequence of a human epidermal keratin: divergence of sequence but conservation of structure among intermediate filament proteins". Cell. 31 (1): 243–52. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(82)90424-X. PMID 6186381.

- Hanukoglu I, Fuchs E (July 1983). "The cDNA sequence of a Type II cytoskeletal keratin reveals constant and variable structural domains among keratins". Cell. 33 (3): 915–24. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90034-X. PMID 6191871.

- Lee CH, Kim MS, Chung BM, Leahy DJ, Coulombe PA (July 2012). "Structural basis for heteromeric assembly and perinuclear organization of keratin filaments". Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19 (7): 707–15. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2330. PMC 3864793. PMID 22705788.

- Hanukoglu I, Ezra L (Jan 2014). "Proteopedia: Coiled-coil structure of keratins". Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 42 (1): 93–94. doi:10.1002/bmb.20746. PMID 24265184.

- Qin Z, Kreplak L, Buehler MJ (2009). "Hierarchical structure controls nanomechanical properties of vimentin intermediate filaments". PLoS ONE. 4 (10): e7294. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7294Q. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007294. PMC 2752800. PMID 19806221.

- Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, et al. (2000). Molecular Cell Biology. New York: W. H. Freeman. p. Section 19.6, Intermediate Filaments. ISBN 978-0-07-243940-3.

- Wang Q, Tolstonog GV, Shoeman R, Traub P (August 2001). "Sites of nucleic acid binding in type I-IV intermediate filament subunit proteins". Biochemistry. 40 (34): 10342–9. doi:10.1021/bi0108305. PMID 11513613.

- Shoeman RL, Huttermann C, Hartig R, Traub P (January 2001). "Amino-terminal polypeptides of vimentin are responsible for the changes in nuclear architecture associated with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease activity in tissue culture cells". Mol. Biol. Cell. 12 (1): 143–54. doi:10.1091/mbc.12.1.143. PMC 30574. PMID 11160829.

- Takemura M, Gomi H, Colucci-Guyon E, Itohara S (August 2002). "Protective role of phosphorylation in turnover of glial fibrillary acidic protein in mice". J. Neurosci. 22 (16): 6972–9. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06972.2002. PMC 6757867. PMID 12177195.

- Parry DA, Marekov LN, Steinert PM, Smith TA (2002). "A role for the 1A and L1 rod domain segments in head domain organization and function of intermediate filaments: structural analysis of trichocyte keratin". J. Struct. Biol. 137 (1–2): 97–108. doi:10.1006/jsbi.2002.4437. PMID 12064937.

- Quinlan R, Hutchison C, Lane B (1995). "Intermediate filament proteins". Protein Profile. 2 (8): 795–952. PMID 8771189.

- Helfand, Brian T.; Chang, Lynne; Goldman, Robert D. (15 January 2004). "Intermediate filaments are dynamic and motile elements of cellular architecture". Journal of Cell Science. 117 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1242/jcs.00936. PMID 14676269. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Herrmann H, Bär H, Kreplak L, Strelkov SV, Aebi U (July 2007). "Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8 (7): 562–73. doi:10.1038/nrm2197. PMID 17551517.Qin Z, Kreplak L, Buehler MJ (2009). "Hierarchical structure controls nanomechanical properties of vimentin intermediate filaments". PLoS ONE. 4 (10): e7294. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7294Q. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007294. PMC 2752800. PMID 19806221.Kreplak L, Fudge D (January 2007). "Biomechanical properties of intermediate filaments: from tissues to single filaments and back". BioEssays. 29 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1002/bies.20514. PMID 17187357.Qin Z, Buehler MJ, Kreplak L (January 2010). "A multi-scale approach to understand the mechanobiology of intermediate filaments". J Biomech. 43 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.004. PMID 19811783.Qin Z, Kreplak L, Buehler MJ (October 2009). "Nanomechanical properties of vimentin intermediate filament dimers". Nanotechnology. 20 (42): 425101. Bibcode:2009Nanot..20P5101Q. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/20/42/425101. PMID 19779230.

- Kollmar, M (29 May 2015). "Polyphyly of nuclear lamin genes indicates an early eukaryotic origin of the metazoan-type intermediate filament proteins". Scientific reports. 5: 10652. doi:10.1038/srep10652. PMID 26024016.

- Klauke B, Kossmann S, Gaertner A, Brand K, Stork I, Brodehl A, Dieding M, Walhorn V, Anselmetti D, Gerdes D, Bohms B, Schulz U, Zu Knyphausen E, Vorgerd M, Gummert J, Milting H (December 2010). "De novo desmin-mutation N116S is associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy". Hum. Mol. Genet. 19 (23): 4595–607. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq387. PMID 20829228.

- Brodehl A, Hedde PN, Dieding M, Fatima A, Walhorn V, Gayda S, Šarić T, Klauke B, Gummert J, Anselmetti D, Heilemann M, Nienhaus GU, Milting H (May 2012). "Dual color photoactivation localization microscopy of cardiomyopathy-associated desmin mutants". J. Biol. Chem. 287 (19): 16047–57. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.313841. PMC 3346104. PMID 22403400.

Further reading

- Herrmann H, Harris JR, eds. (1998). Intermediate filaments. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-45854-5.

- Omary MB, Coulombe PA, eds. (2004). Intermediate filament cytoskeleton. Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 978-0-12-564173-9.

- Paramio JM, ed. (2006). Intermediate filaments. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-33780-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Intermediate filament protein, coiled coil region. |

- Intermediate+Filament+Proteins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)