History of the periodic table

The periodic table is an arrangement of the chemical elements, which are organized on the basis of their atomic numbers, electron configurations and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number. The standard form of the table consists of a grid with rows called periods and columns called groups.

%2C_black_and_white.png)

The history of the periodic table reflects over two centuries of growth in the understanding of the chemical and physical properties of the elements, with major contributions made by Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner, John Newlands, Julius Lothar Meyer, Dmitri Mendeleev, Glenn T. Seaborg, and others.[1][2]

Early history

A number of physical elements (such as platinum, mercury, tin, and zinc) have been known from antiquity, as they are found in their native form and are relatively simple to mine with primitive tools.[3] Around 330 BCE, the Greek philosopher Aristotle proposed that everything is made up of a mixture of one or more roots, an idea that had originally been suggested by the Sicilian philosopher Empedocles. The four roots, which were later renamed as elements by Plato, were earth, water, air and fire. Similar ideas about these four elements also existed in other ancient traditions, such as Indian philosophy.

First categorizations

The history of the periodic table is also a history of the discovery of the chemical elements. The first person in history to discover a new element was Hennig Brand, a bankrupt German merchant. Brand tried to discover the Philosopher's Stone—a mythical object that was supposed to turn inexpensive base metals into gold. In 1669 (or later), his experiments with distilled human urine resulted in the production of a glowing white substance, which he called "cold fire" (kaltes Feuer).[4] He kept his discovery secret until 1680, when Irish chemist Robert Boyle rediscovered phosphorus and published his findings. The discovery of phosphorus helped to raise the question of what it meant for a substance to be an element.

In 1661, Boyle defined an element as "those primitive and simple Bodies of which the mixt ones are said to be composed, and into which they are ultimately resolved."[5]

In 1789, French chemist Antoine Lavoisier wrote Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elementary Treatise of Chemistry), which is considered to be the first modern textbook about chemistry. Lavoisier defined an element as a substance that cannot be broken down into a simpler substance by a chemical reaction.[6] This simple definition served for a century and lasted until the discovery of subatomic particles. Lavoisier's book contained a list of "simple substances" that Lavoisier believed could not be broken down further, which included oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, phosphorus, mercury, zinc and sulfur, which formed the basis for the modern list of elements. Lavoisier's list also included 'light' and 'caloric', which at the time were believed to be material substances. He classified these substances into metals and nonmetals. While many leading chemists refused to believe Lavoisier's new revelations, the Elementary Treatise was written well enough to convince the younger generation. However, Lavoisier's descriptions of his elements lack completeness, as he only classified them as metals and non-metals.

In 1815, British physician and chemist William Prout noticed that atomic weights seemed to be multiples of that of hydrogen.[7]

In 1817, German physicist Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner began to formulate one of the earliest attempts to classify the elements.[8] In 1829, he found that he could form some of the elements into groups of three, with the members of each group having related properties. He termed these groups triads.[9]

Definition of Triad law:-"Chemically analogous elements arranged in increasing order of their atomic weights formed well marked groups of three called Triads in which the atomic weight of the middle element was found to be generally the arithmetic mean of the atomic weight of the other two elements in the triad.

- chlorine, bromine, and iodine

- calcium, strontium, and barium

- sulfur, selenium, and tellurium

- lithium, sodium, and potassium

In 1860, a revised list of elements and atomic masses was presented at a conference in Karlsruhe. It helped spur creation of more extensive systems. The first such system emerged in two years.[10]

Comprehensive formalizations

Properties of the elements, and thus properties of light and heavy bodies formed by them, are in a periodic dependence on their atomic weight.

— Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, formulating the periodic law for the first time in his 1871 article "Periodic regularity of the chemical elements"[11]

French geologist Alexandre-Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois noticed that the elements, when ordered by their atomic weights, displayed similar properties at regular intervals. In 1862, he devised a three-dimensional chart, named the "telluric helix", after the element tellurium, which fell near the center of his diagram.[12][13] With the elements arranged in a spiral on a cylinder by order of increasing atomic weight, de Chancourtois saw that elements with similar properties lined up vertically. The original paper from Chancourtois in Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences did not include a chart and used geological rather than chemical terms. In 1863, he extended his work by including a chart and adding ions and compounds.[14]

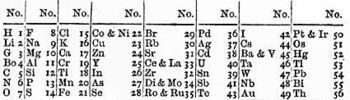

The next attempt was made in 1864. British chemist John Newlands presented a classification of the 62 known elements. Newlands noticed recurring trends in physical properties of the elements at recurring intervals of multiples of eight in order of mass number;[15] based on this observation, he produced a classification of these elements into eight groups. Each group displayed a similar progression; Newlands likened these progressions to the progression of notes within a musical scale.[16][17][18][13] Newlands's table left no gaps for possible future elements, and in some cases had two elements at the same position in the same octave. Newlands's table was ridiculed by some of his contemporaries. The Chemical Society refused to publish his work. The president of the Society, William Odling, defended the Society's decision by saying that such 'theoretical' topics might be controversial;[19] there was even harsher opposition from within the Society, suggesting the elements could have been just as well listed alphabetically.[10] Later that year, Odling suggested a table of his own[20] but failed to get recognition following his role in opposing Newlands's table.[19]

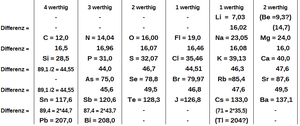

German chemist Lothar Meyer also noted the sequences of similar chemical and physical properties repeated at periodic intervals. According to him, if the atomic weights were plotted as ordinates (i.e. vertically) and the atomic volumes as abscissae (i.e. horizontally)—the curve obtained a series of maximums and minimums—the most electropositive elements would appear at the peaks of the curve in the order of their atomic weights. In 1864, a book of his was published; it contained an early version of the periodic table containing 28 elements, and classified elements into six families by their valence—for the first time, elements had been grouped according to their valence. Works on organizing the elements by atomic weight had until then been stymied by inaccurate measurements of the atomic weights.[21] In 1868, he revised his table, but this revision was published as a draft only after his death. In a paper dated December 1869 which appeared early in 1870, Meyer published a new periodic table of 55 elements, in which the series of periods are ended by an element of the alkaline earth metal group. The paper also included a line chart of relative atomic volumes, which illustrated periodic relationships of physical characteristics of the elements, and which assisted Meyer in deciding where elements should appear in his periodic table. By this time he had already seen the publication of Mendeleev's first periodic table, but his work appears to have been largely independent.[3]

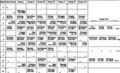

Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev arranged the elements by atomic mass, corresponding to relative molar mass. It is sometimes said that he played "chemical solitaire" on long train journeys,[22] using cards with the symbols and the atomic weights of the known elements. Another possibility is that he was inspired in part by the periodicity of the Sanskrit alphabet, which was pointed out to him by his friend and linguist Otto von Böhtlingk.[23] Mendeleev used the trends he saw to suggest that atomic weights of some elements were incorrect and accordingly changed their placing: for instance, he figured there was no place for a trivalent beryllium with the mass of 14 in his work, and he cut both the atomic weight and valency of beryllium by a third, suggesting it was a divalent element with the atomic weight of 9.4. Mendeleev also figured some spots in his ordering had no element to match, and he left gaps on account of future discoveries of these elements, using the elements before and after those missing ones to predict their properties. In 1869, he finalized his first work and had it published.[24][25] Mendeleev also sent it to a number of well-known chemists, including Meyer; this preceded Meyer's first comprehensive periodic table which he published a few months later, acknowledging Mendeleev's priority.[26] Mendeleev continued to improve his ordering; in 1870, it gained a tabular shape, and in 1871, it was titled "periodic table". Some changes also occurred with new revisions, with some elements changing positions.

- Various attempts to construct a comprehensive formalization

Meyer's periodic table, published in "Die modernen Theorien der Chemie", 1864[21]

Meyer's periodic table, published in "Die modernen Theorien der Chemie", 1864[21] Newlands's law of octaves, 1866

Newlands's law of octaves, 1866 Mendeleev's first Attempt at a system of elements, 1869

Mendeleev's first Attempt at a system of elements, 1869 Mendeleev's Natural system of the elements, 1870

Mendeleev's Natural system of the elements, 1870 Mendeleev's periodic table, 1871

Mendeleev's periodic table, 1871

Priority dispute and recognition

That person is rightly regarded as the creator of a particular scientific idea who perceives not merely its philosophical, but its real aspect, and who understands so to illustrate the matter so that everyone can become convinced of its truth. Then alone the idea, like matter, becomes indestructible.

— Mendeleev in his 1881 article in British journal Chemical News in a correspondence debate with Meyer over priority of the periodic table invention[27]

Initial fate of the categorization proposals

None of the proposals was accepted immediately, and many contemporary chemists found it too abstract to have any meaningful value. Of those chemists that proposed their categorizations, Mendeleev stood out as he strove to back his work and promote his vision of periodicity. In contrast, Meyer did not promote his work very actively, and Newlands did not make a single attempt to gain recognition abroad.

Mendeleev's predictions and inability to incorporate the rare earth metals

| Name | Mendeleev's atomic weight | Modern atomic weight | Modern name (year of discovery) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ether | 0.17 | — | — |

| Coronium | 0.4 | — | — |

| Eka-boron | 44 | 44.6 | Scandium |

| Eka-cerium | 54 | — | — |

| Eka-aluminum | 68 | 69.2 | Gallium |

| Eka-silicon | 72 | 72.0 | Germanium |

| Eka-manganese | 100 | 99 | Technetium (1925) |

| Eka-molybdenum | 140 | — | — |

| Eka-niobium | 146 | — | — |

| Eka-cadmium | 155 | — | — |

| Eka-iodine | 170 | — | — |

| Tri-manganese | 190 | 186 | Rhenium (1925) |

| Eka-caesium | 175 | — | — |

| Dvi-tellurium | 212 | 210 | Polonium (1898) |

| Dvi-caesium | 220 | 223 | Francium (1937) |

| Eka-tantalum | 235 | 231 | Protactinium (1917) |

In addition to the predictions of scandium, gallium, and germanium that were quickly realized, Mendeleev's 1871 table left many more spaces for undiscovered elements, though he did not provide detailed predictions of their properties. In total, he predicted eighteen elements, though only half corresponded to elements that were later discovered.[30]

Even as Mendeleev corrected positions of some elements, he thought that some relationships that he could find in his grand scheme of periodicity could not be found because some elements were still undiscovered, and thus he believed these elements that were still undiscovered would have properties that could be deduced from the expected relationships with other elements. In 1870, he first tried to characterize the yet undiscovered elements, and he gave detailed predictions for three elements, which he termed eka-boron, eka-aluminium, and eka-silicium,[31] as well as more briefly noted a few other expectations.[32] In 1871, he expanded his predictions further.

Compared to the rest of the work, Mendeleev's 1869 list misplaces seven then-known elements: indium, thorium, and the five rare earth metals—yttrium, cerium, lanthanum, erbium, and didymium (the latter two were later found to be mixtures of different elements); ignoring those would allow him to restore the logic of increasing atomic weight. These elements (all thought to be divalent at the time) puzzled Mendeleev in that they did not show gradual increase in valency despite their seemingly consequential atomic weights.[33] Mendeleev grouped them together, thinking of them as of a particular kind of series.[lower-alpha 2] In early 1870, he decided the weights for these elements must be wrong and that the rare earth metals should be trivalent (which accordingly increases their weights by half). He measured heat capacity of indium, uranium, and cerium to demonstrate their increase of accounted valency (which was soon confirmed by Prussian chemist Robert Bunsen).[34] Mendeleev considered the change by assessing each element an individual place in his system of the elements.

Mendeleev noticed that there was a significant difference in atomic mass between cerium and tantalum with no element between them; his consideration was that between them, there was a row of yet undiscovered elements, which would display similar properties to those elements which were to be found above and below them: for instance, an eka-molybdenum would behave as a heavier homolog of molybdenum and a lighter homolog of wolfram (the name under which Mendeleev knew tungsten).[35] This row would begin with a trivalent lanthanum, a teravalent cerium, and a pentavalent didymium. However, the higher valency for didymium had not been established, and Mendeleev tried to do that himself.[36] Having had no success in that, he abandoned his attempts to incorporate the rare earth metals in late 1871 and embarked on his grand idea of luminiferous ether. His idea was carried on by Austrian-Hungarian chemist Bohuslav Brauner, who sought to find a place in the periodic table for the rare earth metals;[37] Mendeleev later referred to him as to "one of the true consolidators of the periodic law".[lower-alpha 3]

Recognition of Mendeleev's table

Eventually, the periodic table was appreciated for its descriptive power and for finally systematizing the relationship between the elements,[39] although such appreciation was not universal.[40] In 1881, Mendeleev and Meyer had an argument via an exchange of articles in British journal Chemical News over priority of the periodic table, which included an article from Mendeleev, one from Meyer, one of critique of the notion of periodicity, and many more.[41] In 1882, the Royal Society in London awarded the Davy Medal to both Mendeleev and Meyer for their work to classify the elements; although two of Mendeleev's predicted elements had been discovered by then, Mendeleev's predictions were not at all mentioned in the prize rationale.

Mendeleev's eka-aluminium was discovered in 1875 and became known as gallium; eka-boron and eka-silicium were discovered in 1879 and 1886, respectively, and were named scandium and germanium.[13] Mendeleev was even able to correct some initial measurements with his predictions, including the first prediction of gallium, which matched eka-aluminium fairly closely but had a different density. Mendeleev advised the discoverer, French chemist Paul Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran, to measure the density again; de Boisbaudran was initially skeptical (not least because he thought Mendeleev was trying to take credit from him) but eventually admitted correctness of the prediction. Mendeleev contacted all three discoverers; all three noted the close similarity of their discovered elements with Mendeleev's predictions, with the last of them, German chemist Clemens Winkler, doing so prior to correspondence with Mendeleev. Some contemporary chemists were not convinced by these discoveries, noting the dissimilarities between the new elements and the predictions or claiming those similarities that did exist were coincidental,[40] but later chemists used the successes of these Mendeleev's predictions to justify his table.[10]

After the three discoveries closely matched Mendeleev's three detailed predictions, his table was widely recognized. In 1889, Mendeleev noted at the Faraday Lecture to the Royal Institution in London that he had not expected to live long enough "to mention their discovery to the Chemical Society of Great Britain as a confirmation of the exactitude and generality of the periodic law".[42]

Inert gases and ether

The match of at[omic] weights of the argonic elements with at[omic] weights of the halogens and the alkali metals was verbally reported to me on March 19, 1900, by prof. Ramsay in Berlin, who then published it in Phylosophical Transactions. For him, this was very important as an affirmation of the position of the newly discovered elements among other known ones, and for me, as a new brilliant affirmation of the generality of the periodic law. For my part, I was silent when I was repeatedly vilified to the argonic elements, as a reproach to the periodic system, for I waited for the opposite to be visible to everyone soon.

— Mendeleev in his 1902 book Attempt of chemical understanding of the world ether[43]

Inert gases

British chemist Henry Cavendish, the discoverer of hydrogen in 1766, discovered that air is composed of more gases than nitrogen and oxygen.[44] He recorded these findings in 1784 and 1785; among them, he found a then-unidentified gas less reactive than nitrogen. Helium was first reported in 1868; the report was based on the new technique of spectroscopy and some spectral lines emitted by the Sun did not match those of any of the known elements. Mendeleev was not convinced by this finding since variance of temperate led to change of intensity of spectral lines and their location on the spectrum;[45] this opinion was held by some other scientists of the day. Others believed the spectral lines could belong to an element that occurred on the Sun but not Earth; some believed it was yet to be found on Earth.

In 1894, British chemist William Ramsay and British physicist Lord Rayleigh isolated argon from air and determined that it was a new element. Argon, however, did not engage in any chemical reactions and was—highly unusually for a gas—monatomic;[lower-alpha 4] it did not fit into the periodic law and thus challenged the very notion of it. Not all scientists immediately accepted this report; Mendeleev's original response to that was that argon was a triatomic form of nitrogen rather than an element of its own.[47] The next year, Ramsay tested a report of American chemist William Francis Hillebrand, who found a steam of an unreactive gas from a sample of uraninite. Wishing to prove it was nitrogen, Ramsay analyzed a different uranium mineral, cleveite, and found a new element, which he named krypton. This finding was corrected by British chemist William Crookes, who matched its spectrum to that of the Sun's helium.[48] Following this discovery, Ramsay, using fractional distillation to separate air, discovered several more such gases in 1898: metargon, krypton, neon, and xenon; detailed spectroscopic analysis of the first of these demonstrated it was argon contaminated by a carbon-based impurity. Ramsay's remaining five unreactive substances were called the inert gases (now noble gases). Although Mendeleev's table predicted several undiscovered elements, it did not predict the existence of such inert gases, and Mendeleev originally rejected those findings as well.[49]

Changes to the periodic table

In 1898, when only helium, argon, and krypton were definitively known, Crookes suggested these elements be placed between the hydrogen group and the fluorine group.[50] In 1900, at the Prussian Academy of Sciences, Ramsay and Mendeleev discussed the new inert gases and their location in the periodic table; Ramsay proposed that these elements be put in a brand new group 0, to which Mendeleev agreed.[51] Two weeks before that discussion, Belgian botanist Léo Errera proposed the same idea, that of a group 0, to the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium; after Mendeleev learned about this proposal, he referred to Errera as to the first person to suggest the idea.[51] Mendeleev himself added these elements to the table as group 0 in 1902, without disturbing the basic concept of the periodic table.[51][52]

In 1905, Swiss chemist Alfred Werner resolved the dead zone of Mendeleev's table. He determined that the rare earth elements (lanthanides), 13 of which were known, lay within that gap. Although Mendeleev knew of lanthanum, cerium, and erbium, they were previously unaccounted for in the table because their total number and exact order were not known; Mendeleev still could not fit them in his table by 1901.[49] This was in part a consequence of their similar chemistry and imprecise determination of their atomic masses. Combined with the lack of a known group of similar elements, this rendered the placement of the lanthanides in the periodic table difficult.[53] This discovery led to a restructuring of the table and the first appearance of the 32-column form.[54]

Ether

By 1904, Mendeleev's table rearranged several elements, and included the noble gases along with most other newly discovered elements. It still had the dead zone, and a row zero was added above hydrogen and helium to include coronium and the ether, which were widely believed to be elements at the time.[54] Although the Michelson-Morley Experiment in 1887 cast doubt on the possibility of a luminiferous ether as a space-filling medium, physicists set constraints for its properties.[55] Mendeleev believed it to be a very light gas, with an atomic weight several orders of magnitude smaller than that of hydrogen. He also postulated that it would rarely interact with other elements, similar to the noble gases of his group zero, and instead permeate substances at a velocity of 2,250 kilometres (1,400 mi) per second.

Mendeleev was not satisfied with the lack of understand of the nature of this periodicity; this would only be possible with the understanding of composition of atom. However, Mendeleev firmly believed that future would only develop the notion rather than challenge it and reaffirmed his belief in writing in 1902.[56]

- Early developments of Mendeleev's table

Mendeleev's 1904 table. It includes the noble gases in group 0, and scandium, gallium, germanium, and radium are added. It has gaps in row 0 (hypothesized elements lighter than hydrogen) and row 9 (lanthanides).

Mendeleev's 1904 table. It includes the noble gases in group 0, and scandium, gallium, germanium, and radium are added. It has gaps in row 0 (hypothesized elements lighter than hydrogen) and row 9 (lanthanides)..gif) Werner's 32-column 1905 table. This table left spaces for many then-unknown elements, and several elements had their positions revised following advances in atomic theory.

Werner's 32-column 1905 table. This table left spaces for many then-unknown elements, and several elements had their positions revised following advances in atomic theory.

Atomic theory and isotopes

Radioactivity and the Rutherford model

Four radioactive elements were known in 1900: radium, actinium, thorium, and uranium. These radioactive elements (termed "radioelements") were accordingly placed at the bottom of the periodic table, as they were known to have greater atomic weights than stable elements, although their exact order was not known. Researchers believed there were still more radioactive elements yet to be discovered, and during the next decade, the decay chains of thorium and uranium were extensively studied. Many new radioactive substances were found, including the noble gas radon, and their chemical properties were investigated.[13] By 1912, almost 50 different radioactive substances had been found in the decay chains of thorium and uranium. American chemist Bertram Boltwood proposed several decay chains linking these radioelements between uranium and lead. These were thought at the time to be new chemical elements, substantially increasing the number of known "elements" and leading to speculations that their discoveries would undermine the concept of the periodic table.[30] For example, there was not enough room between lead and uranium to accommodate these discoveries, even assuming that some discoveries were duplicates or incorrect identifications. It was also believed that radioactive decay violated one of the central principles of the periodic table, namely that chemical elements could not undergo transmutations and always had unique identities.[13]

Frederick Soddy and Kazimierz Fajans found in 1913 that although these substances emitted different radiation,[57] many of these substances were identical in their chemical characteristics, so shared the same place on the periodic table.[58][59] They became known as isotopes, from the Greek isos topos ("same place").[13][60] Austrian chemist Friedrich Paneth cited a difference between "real elements" (elements) and "simple substances" (isotopes), also determining that the existence of different isotopes was mostly irrelevant in determining chemical properties.[30]

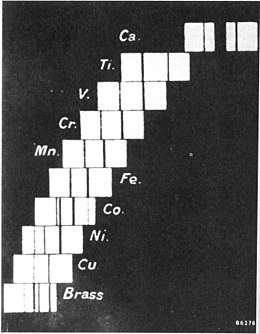

Following British physicist Charles Glover Barkla's discovery of characteristic X-rays emitted from metals in 1906, British physicist Henry Moseley considered a possible correlation between x-ray emissions and physical properties of elements. Moseley, along with Charles Galton Darwin, Niels Bohr, and George de Hevesy, proposed that the nuclear charge (Z) or atomic mass may be mathematically related to physical properties.[61] The significance of these atomic properties was determined in the Geiger-Marsden experiment, in which the atomic nucleus and its charge were discovered.[62]

Atomic number

In 1913, amateur Dutch physicist Antonius van den Broek was the first to propose that the atomic number (nuclear charge) determined the placement of elements in the periodic table. He correctly determined the atomic number of all elements up to atomic number 50 (tin), though he made several errors with heavier elements. However, Van den Broek did not have any method to experimentally verify the atomic numbers of elements; thus, they were still believed to be a consequence of atomic weight, which remained in use in ordering elements.[61]

Moseley was determined to test Van den Broek's hypothesis.[61] After a year of investigation of the Fraunhofer lines of various elements, he found a relationship between the X-ray wavelength of an element and its atomic number.[63] With this, Moseley obtained the first accurate measurements of atomic numbers and determined an absolute sequence to the elements, allowing him to restructure the periodic table. Moseley's research immediately resolved discrepancies between atomic weight and chemical properties, where sequencing strictly by atomic weight would result in groups with inconsistent chemical properties. For example, his measurements of X-ray wavelengths enabled him to correctly place argon (Z = 18) before potassium (Z = 19), cobalt (Z = 27) before nickel (Z = 28), as well as tellurium (Z = 52) before iodine (Z = 53), in line with periodic trends. The determination of atomic numbers also clarified the order of chemically similar rare earth elements; it was also used to confirm that Georges Urbain's claimed discovery of a new rare earth element (celtium) was invalid, earning Moseley acclamation for this technique.[61]

Swedish physicist Karl Siegbahn continued Moseley's work for elements heavier than gold (Z = 79), and found that the heaviest known element at the time, uranium, had atomic number 92. In determining the largest identified atomic number, gaps in the atomic number sequence were conclusively determined where an atomic number had no known corresponding element; the gaps occurred at atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, and 87.[61]

Electron shell and quantum mechanics

In 1914, Swedish physicist Johannes Rydberg noticed that the atomic numbers of the noble gases was equal to doubled sums of squares of simple numbers: 2 = 2·12, 10 = 2(12 + 22), 18 = 2(12 + 22 + 22), 36 = 2(12 + 22 + 22 + 32), 54 = 2(12 + 22 + 22 + 32 + 32), 86 = 2(12 + 22 + 22 + 32 + 32 + 42). This finding was accepted as an explanation of the fixed lengths of periods and led to repositioning of the noble gases from the left edge of the table to the right.[51] Unwillingness of the noble gases to engage in chemical reaction was explained in the alluded stability of closed noble gas electron configurations; from this notion emerged the octet rule.[51] Among the notable works that established the importance of the periodicity of eight were the valence bond theory, published in 1916 by American chemist Gilbert N. Lewis[64] and the octet theory of chemical bonding, published in 1919 by American chemist Irving Langmuir.[65][66]

In the 1910s and 1920s, pioneering research into quantum mechanics led to new developments in atomic theory and small changes to the periodic table. The Bohr model was developed during this time, and championed the idea of electron configurations that determine chemical properties. Bohr proposed that elements in the same group behaved similarly because they have similar electron configurations, and that noble gases had filled valence shells;[67] this forms the basis of the modern octet rule. This research then led Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli to investigate the length of periods in the periodic table in 1924. Mendeleev asserted that there was a fixed periodicity of eight, and expected a mathematical correlation between atomic number and chemical properties;[68] Pauli demonstrated that this was not the case. Instead, the Pauli exclusion principle was developed. This states that no electrons can coexist in the same quantum state, and showed, in conjunction with empirical observations, the existence of four quantum numbers and the consequence on the order of shell filling.[67] This determines the order in which electron shells are filled and explains the periodicity of the periodic table.

British chemist Charles Bury is credited with the first use of the term transition metal in 1921 to refer to elements between the main-group elements of groups II and III. He explained the chemical properties of transition elements as a consequence of the filling of an inner subshell rather than the valence shell. This proposition, based upon the work of American chemist Gilbert N. Lewis, suggested the appearance of the d subshell in period 4 and the f subshell in period 6, lengthening the periods from 8 to 18 and then 18 to 32 elements.[69]

Proton and neutron

Later expansions and the end of the periodic table

We already feel that we have neared the moment when this [periodic] law begins to change, and change fast.

— Russian physicist Yuri Oganessian, co-discoverer of several superheavy elements, in 2019[70]

Actinides

As early as 1913, Bohr's research on electronic structure led physicists such as Rydberg to extrapolate the properties of undiscovered elements heavier than uranium. Many agreed that the next noble gas after radon would most likely have the atomic number 118, from which it followed that the transition series in the seventh period should resemble those in the sixth. Although it was thought that these transition series would include a series analogous to the rare earth elements, characterized by filling of the 5f shell, it was unknown where this series began. Predictions ranged from atomic number 90 (thorium) to 99, many of which proposed a beginning beyond the known elements (at or beyond atomic number 93). The elements from actinium to uranium were instead believed to form part of a fourth series of transition metals because of their high oxidation states; accordingly, they were placed in groups 3 through 6.[71]

In 1940, neptunium and plutonium were the first transuranic elements to be discovered; they were placed in sequence beneath rhenium and osmium, respectively. However, preliminary investigations of their chemistry suggested a greater similarity to uranium than to lighter transition metals, challenging their placement in the periodic table.[72] During his Manhattan Project research in 1943, American chemist Glenn T. Seaborg experienced unexpected difficulties in isolating the elements americium and curium, as they were believed to be part of a fourth series of transition metals. Seaborg wondered if these elements belonged to a different series, which would explain why their chemical properties, in particular the instability of higher oxidation states, were different from predictions.[72] In 1945, against the advice of colleagues, he proposed a significant change to Mendeleev's table: the actinide series.[71][73]

Seaborg's actinide concept of heavy element electronic structure proposed that the actinides form an inner transition series analogous to the rare earth series of lanthanide elements—they would comprise the second row of the f-block (the 5f series), in which the lanthanides formed the 4f series. This facilitated chemical identification of americium and curium,[73] and further experiments corroborated Seaborg's hypothesis; a spectroscopic study at the Los Alamos National Laboratory by a group led by American physicist Edwin McMillan indicated that 5f orbitals, rather than 6d orbitals, were indeed being filled. However, these studies could not unambiguously determine the first element with 5f electrons and therefore the first element in the actinide series;[72] it was thus also referred to as the "thoride" or "uranide" series until it was later found that the series began with actinium.[71][74]

In light of these observations and an apparent explanation for the chemistry of transuranic elements, and despite fear among his colleagues that it was a radical idea that would ruin his reputation, Seaborg nevertheless submitted it to Chemical and Engineering News and it gained widespread acceptance; new periodic tables thus placed the actinides below the lanthanides.[73] Following its acceptance, the actinide concept proved pivotal in the groundwork for discoveries of heavier elements, such as berkelium in 1949.[75] It also supported experimental results for a trend towards +3 oxidation states in the elements beyond americium—a trend observed in the analogous 4f series.[71]

Relativistic effects and expansions beyond period 7

Seaborg's subsequent elaborations of the actinide concept theorized a series of superheavy elements in a transactinide series comprising elements from 104 to 121 and a superactinide series of elements from 122 to 153.[72] He proposed an extended periodic table with an additional period of 50 elements (thus reaching element 168); this eighth period was derived from an extrapolation of the Aufbau principle and placed elements 121 to 138 in a g-block, in which a new g subshell would be filled.[76] Seaborg's model, however, did not take into account relativistic effects resulting from high atomic number and electron orbital speed. Burkhard Fricke in 1971[77] and Pekka Pyykkö in 2010[78] used computer modeling to calculate the positions of elements up to Z = 172, and found that the positions of several elements were different from those predicted by Seaborg. Although models from Pyykkö and Fricke generally place element 172 as the next noble gas, there is no clear consensus on the electron configurations of elements beyond 120 and thus their placement in an extended periodic table. It is now thought that because of relativistic effects, such an extension will feature elements that break the periodicity in known elements, thus posing another hurdle to future periodic table constructs.[78]

The discovery of tennessine in 2010 filled the last remaining gap in the seventh period. Any newly discovered elements will thus be placed in an eighth period.

Despite the completion of the seventh period, experimental chemistry of some transactinides has been shown to be inconsistent with the periodic law. In the 1990s, Ken Czerwinski at University of California, Berkeley observed similarities between rutherfordium and plutonium and dubnium and protactinium, rather than a clear continuation of periodicity in groups 4 and 5. More recent experiments on copernicium and flerovium have yielded inconsistent results, some of which suggest that these elements behave more like the noble gas radon rather than mercury and lead, their respective congeners. As such, the chemistry of many superheavy elements has yet to be well-characterized, and it remains unclear whether the periodic law can still be used to extrapolate the properties of undiscovered elements.[2][79]

Shell effects, the island of stability, and the search for the end of the periodic table

See also

- Alternative periodic tables

- History of chemistry

- Periodic Systems of Small Molecules

- Prout's hypothesis

- The Mystery of Matter: Search for the Elements (PBS film)

- Timeline of chemical element discoveries

Notes

- Scerri notes that this table "does not include elements such as astatine and actinium, which he [Mendeleev] predicted successfully but did not name. Neither does it include predictions that were represented just by dashes in Mendeleev’s periodic systems. Among some other failures, not included in the table, is an inert gas element between barium and tantalum, which would have been called ekaxenon, although Mendeleev did not refer to it as such."[29]

- He noted similarity despite sequential atomic weights; he termed such sequences as primary groups (as opposed to regular secondary groups, those in the likes of the halogens or the alkali metals). Other examples of primary groups included set of rhodium, ruthenium, and palladium, and the set of iridium, osmium, and platinum.

- Mendeleev referred to Brauner in this manner after Brauner measured the atomic weight of tellurium and obtained the value 125. Mendeleev had thought that due to the properties tellurium and iodine display, the latter should be the heavier one while the contemporary data pointed otherwise (tellurium was assessed with the value of 128, and iodine 127). Later measurements by Brauner himself, however, showed the correctness of the original measurement; Mendeleev doubted it for the rest of his life.[38]

- The only other monatomic gas known at the time was vaporized mercury.[46]

References

- IUPAC article on periodic table Archived 2008-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Roberts, Siobhan (27 August 2019). "Is It Time to Upend the Periodic Table? - The iconic chart of elements has served chemistry well for 150 years. But it's not the only option out there, and scientists are pushing its limits". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- Scerri, E. R. (2006). The Periodic Table: Its Story ad Its Significance; New York City, New York; Oxford University Press.

- Weeks, Mary (1956). Discovery of the Elements (6th ed.). Easton, Pennsylvania, USA: Journal of Chemical Education. p. 122.

- Boyle, Robert (1661). The Skeptical Chymist. London, England: J. Crooke. p. 16.

- Lavoisier with Robert Kerr, trans. (1790) Elements of Chemistry. Edinburgh, Scotland: William Creech. From p. xxiv: "I shall therefore only add upon this subject, that if, by the term elements, we mean to express those simple and indivisible atoms of which matter is composed, it is extremely probable we know nothing at all about them; but, if we apply the term elements, or principles of bodies, to express our idea of the last point which analysis is capable of reaching, we must admit, as elements, all substances into which we are capable, by any means, to reduce bodies by decomposition. Not that we are entitled to affirm, that these substances we consider as simple may not be compounded of two, or even of a greater number of principles; but, since these principles cannot be separated, or rather since we have not hitherto discovered means of separating them, they act with regard to us as simple substances, and we ought never to suppose them compounded until experiment and observation has proved them to be so."

- See:

- Prout, William (November 1815). "On the relation between the specific gravities of bodies in their gaseous state and the weights of their atoms". Annals of Philosophy. 6: 321–330.

- Prout, William (February 1816). "Correction of a mistake in the essay on the relation between the specific gravities of bodies in their gaseous state and the weights of their atoms". Annals of Philosophy. 7: 111–113.

- Wurzer, Ferdinand (1817). "Auszug eines Briefes vom Hofrath Wurzer, Prof. der Chemie zu Marburg" [Excerpt of a letter from Court Advisor Wurzer, Professor of Chemistry at Marburg]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 56 (7): 331–334. Bibcode:1817AnP....56..331.. doi:10.1002/andp.18170560709. Here, Döbereiner found that strontium's properties were intermediate to those of calcium and barium.

- Döbereiner, J. W. (1829). "Versuch zu einer Gruppirung der elementaren Stoffe nach ihrer Analogie" [An attempt to group elementary substances according to their analogies]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 2nd series (in German). 15 (2): 301–307. Bibcode:1829AnP....91..301D. doi:10.1002/andp.18290910217. For an English translation of this article, see: Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner: "An Attempt to Group Elementary Substances according to Their Analogies" (Lemoyne College (Syracuse, New York, USA))

- "Development of the periodic table". www.rsc.org. Retrieved 2019-07-12.

- Mendeleev 1871, p. 111.

- Beguyer de Chancourtois (1862). "Tableau du classement naturel des corps simples, dit vis tellurique" [Table of the natural classification of elements, called the "telluric helix"]. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 55: 600–601.

- Ley, Willy (October 1966). "The Delayed Discovery". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 116–127.

- Chancourtois, Alexandre-Émile Béguyer de (1863). Vis tellurique. Classement des corps simples ou radicaux, obtenu au moyen d'un système de classification hélicoïdal et numérique (in French). Paris, France: Mallet-Bachelier. 21 pages.

- John Newlands, Chemistry Review, November 2003, pp15-16

- See:

- Newlands, John A. R. (7 February 1863). "On relations among the equivalents". The Chemical News. 7: 70–72.

- Newlands, John A. R. (30 July 1864). "Relations between equivalents". The Chemical News. 10: 59–60.

- Newlands, John A. R. (20 August 1864). "On relations among the equivalents". The Chemical News. 10: 94–95.

- Newlands, John A. R. (18 August 1865). "On the law of octaves". The Chemical News. 12: 83.

- (Editorial staff) (9 March 1866). "Proceedings of Societies: Chemical Society: Thursday, March 1". The Chemical News. 13: 113–114.

- Newlands, John A.R. (1884). On the Discovery of the Periodic Law and on Relations among the Atomic Weights. E. & F.N. Spon: London, England.

- in a letter published in Chemistry News in February 1863, according to the Notable Names Data Base

- "An Unsystematic Foreshadowing: J. A. R. Newlands". web.lemoyne.edu. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- Shaviv, Giora (2012). The Synthesis of the Elements. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. p. 38. ISBN 9783642283857. From p. 38: "The reason [for rejecting Newlands's paper, which was] given by Odling, then the president of the Chemical Society, was that they made a rule not to publish theoretical papers, and this on the quite astonishing grounds that such papers lead to a correspondence of controversial character."

- See:

- Odling, William (June 1857). "On the natural groupings of the elements. Part 1". Philosophical Magazine. 4th series. 13 (88): 423–440. doi:10.1080/14786445708642323.

- Odling, William (1857). "On the natural groupings of the elements. Part 2". Philosophical Magazine. 4th series. 13 (89): 480–497. doi:10.1080/14786445708642334.

- Odling, William (1864). "On the hexatomicity of ferricum and aluminium". Philosophical Magazine. 4th series. 27 (180): 115–119. doi:10.1080/14786446408643634.

- Odling, William (1864). "On the proportional numbers of the elements". Quarterly Journal of Science. 1: 642–648.

- Meyer, Julius Lothar; Die modernen Theorien der Chemie (1864); table on page 137, https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/goToPage/bsb10073411.html?pageNo=147

- Physical Science, Holt Rinehart & Winston (January 2004), page 302 ISBN 0-03-073168-2

- Ghosh, Abhik; Kiparsky, Paul (2019). "The Grammar of the Elements". American Scientist. 107 (6): 350. doi:10.1511/2019.107.6.350. ISSN 0003-0996.

- Менделеев, Д. (1869). "Соотношение свойств с атомным весом элементов" [Relationship of properties of the elements to their atomic weights]. Журнал Русского Химического Общества (Journal of the Russian Chemical Society) (in Russian). 1: 60–77.

- Mendeleev, Dmitri (1869). "Ueber die Beziehungen der Eigenschaften zu den Atomgewichten der Elemente" [On the relations of properties of the elements to their atomic weights]. Zeitschrift für Chemie. 12: 405–406.

- Alan J. Rocke (1984). Chemical Atomism in the Nineteenth Century: From Dalton to Cannizzaro. Ohio State University Press.

- Scerri 2019, p. 147.

- Scerri 2019, p. 142.

- Scerri 2019, p. 143.

- Scerri, E.R. (2008). "The past and future of the periodic table". American Scientist. 96 (1): 52–58. doi:10.1511/2008.69.52.

- Mendeleev 1870, pp. 90–98.

- Mendeleev 1870, pp. 98–101.

- Thyssen & Binnemans 2015, p. 159.

- Thyssen & Binnemans 2015, pp. 174–175.

- Cheisson, T.; Schelter, E. J. (2019). "Rare earth elements: Mendeleev's bane, modern marvels". Science. 363 (6426): 489–493. Bibcode:2019Sci...363..489C. doi:10.1126/science.aau7628. PMID 30705185.

- Thyssen & Binnemans 2015, p. 177.

- Thyssen & Binnemans 2015, pp. 179–181.

- Scerri 2019, pp. 130-131.

- Scerri, Eric R. (1998). "The Evolution of the Periodic System". Scientific American. 279 (3): 78–83. Bibcode:1998SciAm.279c..78S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0998-78. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 26057945.

- Scerri 2019, pp. 170–172.

- Scerri 2019, pp. 147–149.

- "Dmitri Mendeleev". New Scientist. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Mendeleev 1902, p. 492.

- Wisniak, J. (2007). "The composition of air: Discovery of argon". Educación Química. 18 (1): 69–84. doi:10.22201/fq.18708404e.2007.1.65979.

- Assovskaya, A. S. (1984). "Первый век гелия" [The first century of helium]. Гелий на Земле и во Вселенной [Helium on Earth and in the Universe] (in Russian). Leningrad: Nedra.

- Scerri 2019, p. 151.

- Lente, Gábor (2019). "Where Mendeleev was wrong: predicted elements that have never been found". ChemTexts. 5 (3): 17. doi:10.1007/s40828-019-0092-5. ISSN 2199-3793.

- Sears, W. M., Jr. (2015). Helium: The Disappearing Element. Springer. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-3-319-15123-6.

- Stewart, P. J. (2007). "A century on from Dmitrii Mendeleev: Tables and spirals, noble gases, and Nobel prizes". Foundations of Chemistry. 9 (3): 235–245. doi:10.1007/s10698-007-9038-x.

- Crookes, W. (1898). "On the position of helium, argon, and krypton in the scheme of elements". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 63 (389–400): 408–411. doi:10.1098/rspl.1898.0052. ISSN 0370-1662.

- Trifonov, D. N. "Сорок лет химии благородных газов" [Forty years of noble gas chemistry] (in Russian). Moscow State University. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- Mendeleev, D. (1903). Popytka khimicheskogo ponimaniia mirovogo efira (in Russian). St. Petersburg.

An English translation appeared as

Mendeléeff, D. (1904). G. Kamensky (translator) (ed.). An Attempt Towards A Chemical Conception Of The Ether. Longmans, Green & Co. - Cotton, S. (2006). "Introduction to the lanthanides". Lanthanide and Actinide Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-470-01005-1.

- Stewart, P.J. (2019). "Mendeleev's predictions: success and failure". Foundations of Chemistry. 21 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1007/s10698-018-9312-0.

- Michelson, Albert A.; Morley, Edward W. (1887). . American Journal of Science. 34 (203): 333–345. Bibcode:1887AmJS...34..333M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-34.203.333.

- Trifonov, D. N. "Д.И. Менделеев. Нетрадиционный взгляд (II)" [D.I. Mendeleev. An unconventional view (II)] (in Russian). Moscow State University. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- Thoennessen, M. (2016). The Discovery of Isotopes: A Complete Compilation. Springer. p. 5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31763-2. ISBN 978-3-319-31761-8. LCCN 2016935977.

- Soddy, Frederick (1913). "Radioactivity". Annual Reports on the Progress of Chemistry. 10: 262–288. doi:10.1039/ar9131000262.

- Soddy, Frederick (28 February 1913). "The radio-elements and the periodic law". The Chemical News. 107 (2779): 97–99.

- Soddy first used the word "isotope" in: Soddy, Frederick (4 December 1913). "Intra-atomic charge". Nature. 92 (2301): 399–400. Bibcode:1913Natur..92..399S. doi:10.1038/092399c0. See p. 400.

- Marshall, J.L.; Marshall, V.R. (2010). "Rediscovery of the Elements: Moseley and Atomic Numbers" (PDF). The Hexagon. Vol. 101 no. 3. Alpha Chi Sigma. pp. 42–47.

- Rutherford, Ernest; Nuttal, John Mitchell (1913). "Scattering of α-Particles by Gases". Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (154): 702–712. doi:10.1080/14786441308635014.

- Moseley, H.G.J. (1914). "The high-frequency spectra of the elements". Philosophical Magazine. 6th series. 27: 703–713. doi:10.1080/14786440408635141.

- Lewis, Gilbert N. (1916). "The atom and the molecule". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 38 (4): 762–785. doi:10.1021/ja02261a002.

- Langmuir, Irving (1919). "The structure of atoms and the octet theory of valence". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 5 (7): 252–259. Bibcode:1919PNAS....5..252L. doi:10.1073/pnas.5.7.252. PMC 1091587. PMID 16576386.

- Langmuir, Irving (1919). "The arrangement of electrons in atoms and molecules". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 41 (6): 868–934. doi:10.1021/ja02227a002.

- Scerri, E.R. (1998). "The Evolution of the Periodic System" (PDF). Scientific American. 279 (3): 78–83. Bibcode:1998SciAm.279c..78S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0998-78.

- Hettema, H.; Kuipers, T.A.F. (1998). "The periodic table — its formalization, status, and relation to atomic theory". Erkenntnis. 28 (3): 387–408. doi:10.1007/BF00184902 (inactive 2020-04-24).

- Jensen, William B. (2003). "The Place of Zinc, Cadmium, and Mercury in the Periodic Table" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 80 (8): 952–961. Bibcode:2003JChEd..80..952J. doi:10.1021/ed080p952.

- Oganessian, Yu. (2019). "Мы приблизились к границам применимости периодического закона" [We have neared the limits of the periodic law]. Elementy (Interview) (in Russian). Interviewed by Sidorova, Ye. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- Seaborg, G. (1994). "Origin of the Actinide Concept" (PDF). Lanthanides/Actinides: Chemistry. Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. 18 (1 ed.). ISBN 9780444536648. LBL-31179.

- Clark, D.L. (2009). The Discovery of Plutonium Reorganized the Periodic Table and Aided the Discovery of New Elements (PDF) (Report). Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- Clark, D.L.; Hobart, D.E. (2000). "Reflections on the Legacy of a Legend: Glenn T. Seaborg, 1912–1999" (PDF). Los Alamos Science. 26: 56–61.

- Hoffman, D. C. (1996). The Transuranium Elements: From Neptunium and Plutonium to Element 112 (PDF). NATO Advanced Study Institute on "Actinides and the Environment". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

- Trabesinger, A. (2017). "Peaceful berkelium". Nature Chemistry. 9 (9): 924. Bibcode:2017NatCh...9..924T. doi:10.1038/nchem.2845. PMID 28837169.

- Hoffman, D.C; Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G.T. (2000). The Transuranium People: The Inside Story. Imperial College Press. p. 435–436. ISBN 978-1-86094-087-3.

- Fricke, B.; Greiner, W.; Waber, J. T. (1971). "The continuation of the periodic table up to Z = 172. The chemistry of superheavy elements". Theoretica Chimica Acta. 21 (3): 235–260. doi:10.1007/BF01172015.

- Pyykkö, Pekka (2011). "A suggested periodic table up to Z≤ 172, based on Dirac–Fock calculations on atoms and ions". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 13 (1): 161–8. Bibcode:2011PCCP...13..161P. doi:10.1039/c0cp01575j. PMID 20967377.

- Scerri, E. (2013). "Cracks in the periodic table". Scientific American. Vol. 308 no. 6. pp. 68–73. ISSN 0036-8733.

Bibliography

- Mendeleev, D. I. (1958). Kedrov, K. M. (ed.). Периодический закон [The periodic law] (in Russian). Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

- Mendeleev, D. I. (1870). Естественная система элементов и применение ее к указанию свойств неоткрытых элементов [The natural system of the elements and its application to indication of properties of unknown elements]. pp. 102–176.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). Republished from Mendeleev, D. I. (1871). "Естественная система элементовъ и примѣненіе её къ указанію свойствъ неоткрытыхъ элементовъ" [The natural system of the elements and its application to indication of properties of unknown elements]. Journal of the Russian Physico-Chemical Society (in Russian). 3 (2): 25–56. Archived from the original on 2014-03-17.

- Mendeleev, D. I. (1871). Периодическая законность химических элементов [Periodic regularity of the chemical elements]. pp. 102–176.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). Republished from Mendelejeff, D. (1871). "Die periodische Gesetzmässigkeit der Elemente" [Periodic regularity of the chemical elements]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German): 133–229.

- Mendeleev, D. I. (1902). Попытка химического понимания мирового эфира [Attempt of chemical understanding of the world ether]. pp. 470–517.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). Republished from Mendeleev, D. (1905). Попытка химическаго пониманія мірового эѳира [Attempt of chemical understanding of the world ether] (in Russian). M. P. Frolova's typo-lithography. pp. 5–40.

- Scerri, E. R. (2019). The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-091436-3.

- Thyssen, P.; Binnemans, K. (2015). Scerri, E.; McIntyre, L. (eds.). "Mendeleev and the Rare-Earth Crisis". Philosophy of Chemistry. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. Springer Netherlands. 306: 155–182. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9364-3_11. ISBN 978-94-017-9363-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Development of the periodic table (part of a collection of pages that explores the periodic table and the elements) by the Royal Society of Chemistry

- Dr. Eric Scerri's web page, which contains interviews, lectures and articles on various aspects of the periodic system, including the history of the periodic table.

- The Internet Database of Periodic Tables – a large collection of periodic tables and periodic system formulations.

- History of Mendeleev periodic table of elements as a data visualization at Stack Exchange