Golden Temple

The Golden Temple, also known as Harmandir Sahib, meaning "abode of God" (Punjabi pronunciation: [ɦəɾᵊmən̪d̪əɾᵊ saːɦ(ɪ)bᵊ]) or Darbār Sahib, meaning "exalted court" (Punjabi pronunciation: [d̪əɾᵊbaːɾᵊ saːɦ(ɪ)bᵊ]), is a Gurdwara located in the city of Amritsar, Punjab, India.[2][3] It is the holiest Gurdwara and the most important pilgrimage site of Sikhism.[2][4]

| Harmandir Sahib Golden Temple | |

|---|---|

The Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sikhism |

| Location | |

| Location | Amritsar |

| State | Punjab |

| Country | India |

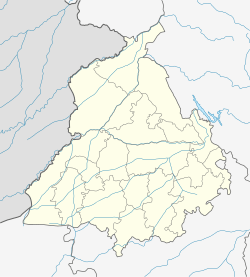

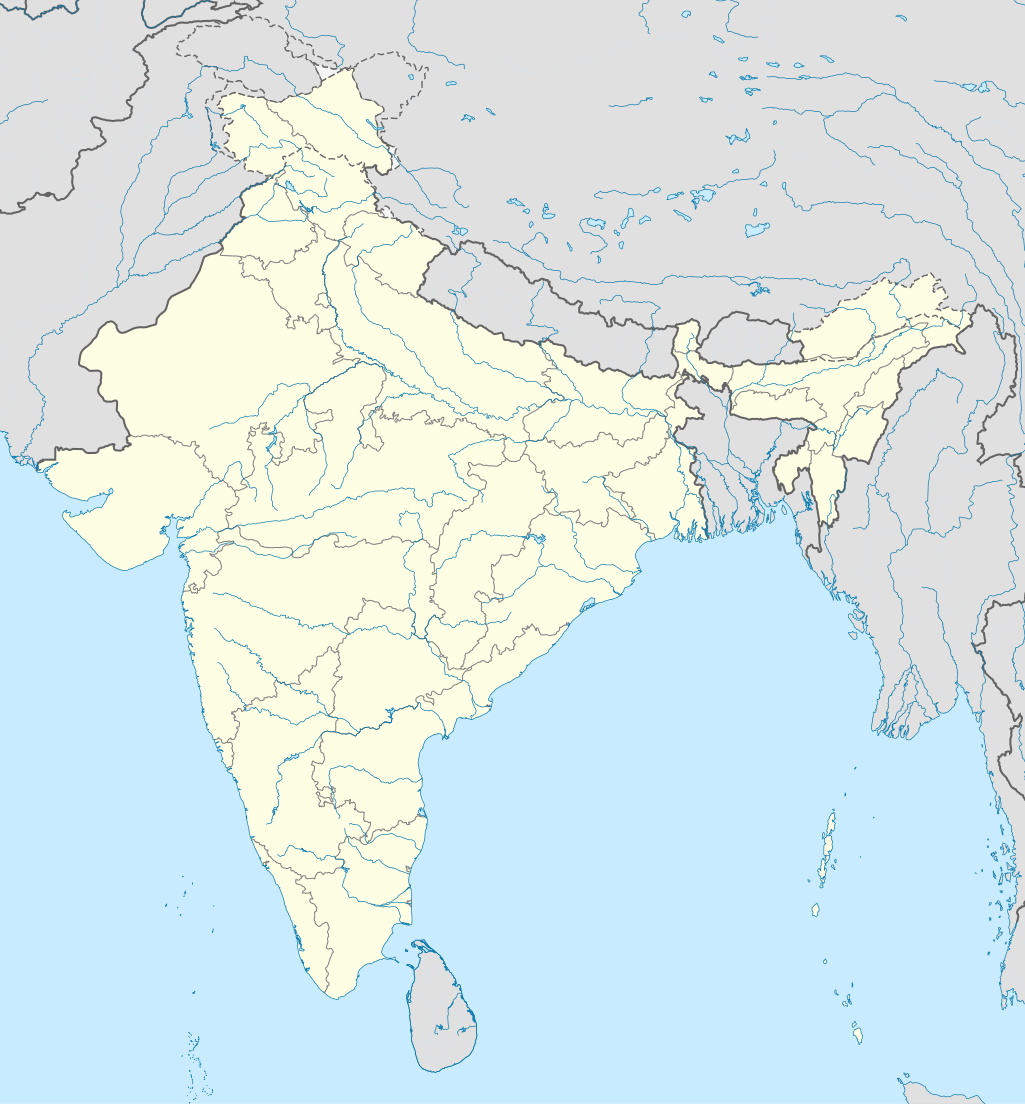

Shown within Punjab  Golden Temple (India)  Golden Temple (Asia) | |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°37′12″N 74°52′37″E |

| Architecture | |

| Groundbreaking | December 1581[1] |

| Completed | 1589 (Temple), 1604 (with Adi Granth) [1] |

| Website | |

| Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee Official Website | |

The temple is built around a man-made pool (sarovar) that was completed by Guru Ram Das in 1577.[5][6] Guru Arjan, the fifth Guru of Sikhism, requested Sai Mir Mian Mohammed, a Muslim Pir of Lahore, to lay its foundation stone in 1589.[7] In 1604, Guru Arjan placed a copy of the Adi Granth in Harmandir Sahib, calling the site Ath Sath Tirath (lit. "shrine of 68 pilgrimages").[2][8] The temple was repeatedly rebuilt by the Sikhs after it became a target of persecution and was destroyed several times by the Muslim armies from Afghanistan and the Mughal Empire.[2][4][9] The army led by Ahmad Shah Abdali, for example, demolished it in 1757 and again in 1762, then filled the pool with garbage and blood of cows.[2][10] Maharaja Ranjit Singh after founding the Sikh Empire, rebuilt it in marble and copper in 1809, overlaid the sanctum with gold foil in 1830. This has led to the name the Golden Temple.[11][12][13]

The temple is spiritually the most significant shrine in Sikhism. It became a center of the Singh Sabha Movement between 1883 and 1920s, and the Punjabi Suba movement between 1947 and 1966. In the early 1980s, the temple became a center of conflict between the Indian government led by Indira Gandhi, some Sikh groups and a militant movement led by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale seeking to create a new nation named Khalistan. In 1984, Indira Gandhi sent in the Indian Army as part of Operation Blue Star, leading to deaths of over 1,000 militants, soldiers and civilians, as well as causing much damage to the temple and the destruction of Akal Takht. The temple complex was rebuilt again after the 1984 damage.[4][14]

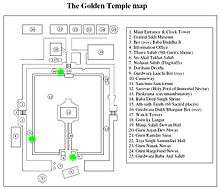

The Harmandir Sahib is an open house of worship for all men and women, from all walks of life and faith.[2] It has a square plan with four entrances, has a circumambulation path around the pool. The temple is a collection of buildings around the sanctum and the pool.[2] One of these is Akal Takht, the chief center of religious authority of Sikhism.[4] Additional buildings include a clock tower, the offices of Gurdwara Committee, a Museum and a langar – a free Sikh community run kitchen that serves a simple vegetarian meal to all visitors without discrimination.[4] Over 100,000 people visit the holy shrine daily for worship.[15] The temple complex has been nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and its application is pending on the tentative list of UNESCO.[16]

Nomenclature

The Harmandar Sahib is also spelled as Harimandar, Harimandir, or Harmandir Sahib.[2] It is also called the Darbār Sahib which means "sacred audience", as well as the Golden Temple for its gold foil covered sanctum center.[4] The word "Harmandir" is composed of two words, "Hari" which scholars variously translate either as "God" or "Vishnu",[2] and "mandir" which means temple or house.[17] The Sikh tradition has several Gurdwaras named "Harmandir Sahib" such as those in Kiratpur and Patna. Of these, the one in Amritsar is most revered.[18][19]

History

According to the Sikh historical records, the land that became Amritsar and houses the Harimandar Sahib was chosen by Guru Amar Das – the third Guru of the Sikh tradition. It was then called Guru Da Chakk, after he had asked his disciple Ram Das to find land to start a new town with a man-made pool as its central point.[20][6][5] After Ram Das succeeded Guru Amar Das in 1574, and given the hostile opposition he faced from the sons of Guru Amar Das,[21] Guru Ram Das founded the town that came to be known as "Ramdaspur". He started by completing the pool with the help of Baba Buddha (not to be confused with the Buddha of Buddhism). Guru Ram Das built his new official centre and home next to it. He invited merchants and artisans from other parts of India to settle into the new town with him.[20]

Ramdaspur town expanded during the time of Guru Arjan financed by donations and constructed by voluntary work. The town grew to become the city of Amritsar, and the area grew into the temple complex).[22] The construction activity between 1574 and 1604 is described in Mahima Prakash Vartak, a semi-historical Sikh hagiography text likely composed in 1741, and the earliest known document dealing with the lives of all the ten Gurus.[23] Guru Arjan installed the scripture of Sikhism inside the new temple in 1604.[24] Continuing the efforts of Guru Ram Das, Guru Arjan established Amritsar as a primary Sikh pilgrimage destination. He wrote a voluminous amount of Sikh scripture including the popular Sukhmani Sahib.[25][26]

Construction

Guru Ram Das acquired the land for the site. Two versions of stories exist on how he acquired this land. In one, based on a Gazetteer record, the land was purchased with Sikh donations of 700 rupees from the owners of the village of Tung. In another version, Emperor Akbar is stated to have donated the land to the wife of Guru Ram Das.[20][27]

In 1581, Guru Arjan initiated the construction of the Gurdwara.[1] During the construction the pool was kept empty and dry. It took 8 years to complete the first version of the Harmandir Sahib. Guru Arjan planned a temple at a level lower than the city to emphasise humility and the need to efface one's ego before entering the premises to meet the Guru.[1] He also demanded that the temple compound be open on all sides to emphasise that it was open to all. The sanctum inside the pool where his Guru seat was had only one bridge to emphasise that the end goal was one, states Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair.[1] In 1589, the temple made with bricks was complete. Guru Arjan is believed by some later sources to have invited the Sufi saint Mian Mir of Lahore to lay its foundation stone, signalling pluralism and that the Sikh tradition welcomed all.[1] This belief is however unsubstantiated.[28][29] According to Sikh traditional sources such as Sri Gur Suraj Parkash Granth it was laid by Guru Arjan himself.[30] After the inauguration, the pool was filled with water. On 16 August 1604, Guru Arjan completed expanding and compiling the first version of the Sikh scripture and placed a copy of the Adi Granth in the temple. He appointed Baba Buddha as the first Granthi.[31]

Guru Arjan called the site Ath Sath Tirath which means "shrine of 68 pilgrimages".[2][8][32] The temple complex marks the place of this announcement with a raised canopy on the parkarma (circumambulation marble path around the pool). The name, state W. Owen Cole and other scholars, reflects the belief that visiting this temple is equivalent to 68 Hindu pilgrimage sites in the Indian subcontinent, or that a Tirath to the Golden Temple has the efficacy of all 68 Tiraths combined.[33][34] The completion of the first version of the Golden Temple was a major milestone for Sikhism, states Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair, because it provided a central pilgrimage place and a rallying point for the Sikh community, set within a hub of trade and activity.[1]

Mughal Empire era destruction and rebuilding

The growing influence and success of Guru Arjan drew the attention of the Mughal Empire. Guru Arjan was arrested under the orders of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir and asked to convert to Islam.[35] He refused, was tortured and executed in 1606 CE.[35][36][37] Guru Arjan's son and successor Guru Hargobind left Amritsar and moved into the Shivalik Hills to avoid persecution and to save the Sikh panth.[38] For about a century after Guru Arjan's martyrdom, state Louis E. Fenech and W. H. McLeod, the Golden Temple was not occupied by the actual Sikh Gurus and it remained in hostile sectarian hands.[38] In the 18th century, Guru Gobind Singh and his newly founded Khalsa Sikhs came back and fought to liberate it.[38] The Golden Temple was viewed by the Mughal rulers and Afghan Sultans as the center of Sikh faith and it remained the main target of persecution.[9]

The Golden Temple was the center of historic events in Sikh history:[39][40]

- In 1709, the governor of Lahore sent in his army to suppress and prevent the Sikhs from gathering for their festivals of Vaisakhi and Divali. But the Sikhs defied by gathering in the Golden Temple. In 1716, Banda Singh and numerous Sikhs were arrested and executed.

- In 1737, the Mughal governor ordered the capture of the custodian of the Golden Temple named Mani Singh and executed him. He appointed Masse Khan as the police commissioner who then occupied the Temple and converted it into his entertainment center with dancing girls. He befouled the pool. Sikhs avenged the sacrilege of the Golden Temple by assassinating Masse Khan inside the Temple in August 1740.

- In 1746, another Lahore official Diwan Lakhpat Rai working for Yahiya Khan, and seeking revenge for the death of his brother, filled the pool with sand. In 1749, Sikhs restored the pool when Muin ul-Mulk slackened Mughal operations against Sikhs and sought their help during his operations in Multan.

- In 1757, the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Durrani, also known as Ahmad Shah Abdali, attacked Amritsar and desecrated the Golden Temple. He had waste poured into the pool along with entrails of slaughtered cows, before departing for Afghanistan. The Sikhs restored it again.

- In 1762, Ahmad Shah Durrani returned and had the Golden Temple blown up with gunpowder. Sikhs returned and celebrated Divali in its premises. In 1764, Baba Jassa Singh Ahluwalia collected donations to rebuild the Golden Temple. A new main gateway (Darshani Deorhi), causeway and sanctum were completed in 1776, while the floor around the pool was completed in 1784. The Sikhs also completed a canal to bring in fresh water from Ravi River for the pool.

Ranjit Singh era reconstruction

Ranjit Singh founded the nucleus of the Sikh Empire at the age of 21 with help of Sukerchakia Misl forces he inherited and those of his mother-in-law Rani Sada Kaur. In 1802, at age 22, he took Amritsar from the Bhangi Sikh misl, paid homage at the Golden Temple and announced that he would renovate and rebuild it with marble and gold.[41] The Temple was renovated in marble and copper in 1809, and in 1830 Ranjit Singh donated gold to overlay the sanctum with gold foil.[40]

After learning of the Temple through Maharaja Ranjit Singh,[42] the 7th Nizam of Hyderabad Mir Osman Ali Khan started giving yearly grants towards it.[43]

The management and operation of Darbar Sahib – a term that refers to the entire Golden Temple complex of buildings, was taken over by Ranjit Singh. He appointed Sardar Desa Singh Majithia (1768–1832) to manage it and made land grants whose collected revenue was assigned to pay for the Temple's maintenance and operation. Ranjit Singh also made the position of Temple officials hereditary.[2]

Description

The Golden Temple's architecture reflects different architectural practices prevalent in the Indian subcontinent, as various iterations of temple were rebuilt and restored. The Temple is described by Ian Kerr, and other scholars, as a mixture of the Indo-Islamic Mughal and the Hindu Rajput architecture.[2][44]

The sanctum is a 12.25 x 12.25 metre square with two-storeys and a gold foil dome. This sanctum has a marble platform that is a 19.7 x 19.7 metre square. It sits inside an almost square (154.5 x 148.5 m2) pool called amritsar or amritsarovar (amrit means nectar, sar is short form of sarovar and means pool). The pool is 5.1 metre deep and is surrounded by a 3.7 metre wide circumambulatory marble passage that is circled clockwise. The sanctum is connected to the platform by a causeway and the gateway into the causeway is called the Darshani Ḍeorhi (from Darshana Dvara). For those who wish to take a dip in the pool, the Temple provides a half hexagonal shelter and holy steps to Har ki Pauri.[2][45] Bathing in the pool is believed by many Sikhs to have restorative powers, purifying one's karma.[46] Some carry bottles of the pool water home particularly for sick friends and relatives.[47] The pool is maintained by volunteers who perform kar seva (community service) by draining and desilting it periodically.[46]

The sanctum has two floors. The Sikh Scripture Guru Granth Sahib is seated on the lower square floor for about 20 hours everyday, and for 4 hours it is taken to its bedroom inside Akal Takht with elaborate ceremonies in a palki, for sukhasana and prakash.[33] The floor with the seated scripture is raised a few steps above the entrance causeway level. The upper floor in the sanctum is a gallery and connected by stairs. The ground floor is lined with white marble, as is the path surrounding the sanctum. The sanctum's exterior has gilded copper plates. The doors are gold foil covered copper sheets with nature motifs such as birds and flowers. The ceiling of the upper floor is gilded, embossed and decorated with jewels. The sanctum dome is semi-spherical with a pinnacle ornament. The sides are embellished with arched copings and small solid domes, the corners adorning cupolas, all of which are covered with gold foil covered gilded copper.[2]

The floral designs on the marble panels of the walls around the sanctum are Arabesque. The arches include verses from the Sikh scripture in gold letters. The frescoes follow the Indian tradition and include animal, bird and nature motifs rather than being purely geometrical. The stair walls have murals of Sikh Gurus such as the falcon carrying Guru Gobind Singh riding a horse.[2][48]

The Darshani Deorhi is a two-storey structure that houses the temple management offices and treasury. At the exit of path leading away from the sanctum is the prasada facility, where volunteers serve a flour-based sweet offering called karah prasad. Typically, the pilgrims to the Golden Temple enter and make a clockwise circumambulation around the pool before entering the sanctum. There are four entrances to the gurdwara complex signifying the openness to all sides, but a single entrance to the sanctum of the temple through a causeway.[2][49]

Akal Takht and Teja Singh Samundri Hall

In front of the sanctum and the causeway is the Akal Takht building. It is the chief Takht, a center of authority in Sikhism. It is also the headquarters of the main political party of the Indian state of Punjab, Shiromani Akali Dal (Supreme Akali Party).[4] The Akal Takht issues edicts or writs (hukam) on matters related to Sikhism and the solidarity of the Sikh community. Its name Akal Takht means "throne of the Timeless (God)". The institution was established by Guru Hargobind after the martyrdom of his father Guru Arjan, as a place to conduct ceremonial, spiritual and secular affairs, issuing binding writs on Sikh Gurdwaras far from his own location. A building was later constructed over the Takht founded by Guru Hargobind, and this came to be known as Akal Bunga. The Akal Takht is also known as Takht Sri Akal Bunga. The Sikh tradition has five Takhts, all of which are major pilgrimage sites in Sikhism. These are in Anandpur, Patna, Nanded, Talwandi Sabo and Amritsar. The Akal Takht in the Golden Temple complex is the primary seat and chief.[50][51]

The Teja Singh Samundri Hall is the office of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (Supreme Committee of Temple Management). It is located in a building near the Langar-kitchen and Assembly Hall. This office coordinates and oversees the operations of major Sikh temples.[4][52]

Ramgarhia Bunga and Clock Tower

The Ramgarhia Bunga – the two high towers visible from the parikrama (circumambulation) walkway around the tank,[54] is named after a Sikh subgroup. The red sandstone minaret-style Bunga (buêgā) towers were built in the 18th-century, a period of Afghan attacks and temple demolitions. It is named after the Sikh warrior and Ramgarhia misl chief Jassa Singh Ramgarhia. It was constructed as the temple watchtowers for sentinels to watch for any military raid approaching the temple and the surrounding area, help rapidly gather a defense to protect the Golden Temple complex. According to Fenech and McLeod, during the 18th-century, Sikh misl chiefs and rich communities built over 70 such Bungas of different shapes and forms around the temple to watch the area, house soldiers and defend the temple.[55] These served defensive purposes, provided accommodation for Sikh pilgrims and served as centers of learning in the 19th-century.[55] Most of the Bungas were demolished during the British colonial era. The Ramgarhia Bunga remains a symbol of the Ramgarhia Sikh community's identity, their historic sacrifices and contribution to defending the Golden Temple over the centuries.[56]

The Clock Tower did not exist in the original version of the temple. In its location was a building, now called the "lost palace". The officials of the British India wanted to demolish the building after the Second Anglo-Sikh war and once they had annexed the Sikh Empire. The Sikhs opposed the demolition, but this opposition was ignored. In its place, the clock tower was added. The clock tower was designed by John Gordon in a Gothic cathedral style with red bricks. The clock tower construction started in 1862 and was completed in 1874. The tower was demolished by the Sikh community about 70 years later. In its place, a new entrance was constructed with a design more harmonious with the Temple. This entrance on the north side has a clock, houses a museum on its upper floor, and it continues to be called ghanta ghar deori.[53][57]

Ber trees

The Golden Temple complex originally was open and had numerous trees around the pool. It is now a walled, two storey courtyard with four entrances, that preserve three Ber trees (jujube). One of them is to the right of the main ghanta ghar deori entrance with the clock, and it is called the Ber Baba Buddha. It is believed in the Sikh tradition to be the tree where Baba Buddha sat to supervise the construction of the pool and first temple.[33][34]

A second tree is called Laachi Ber, believed to the one under which Guru Arjan rested while the temple was being built.[34] The third one is called Dukh Bhanjani Ber, located on the other side of the sanctum, across the pool. It is believed in the Sikh tradition that this tree was the location where a Sikh was cured of his leprosy after taking a dip in the pool, giving the tree the epithet of "suffering remover".[17][58] There is a small Gurdwara underneath the tree.[34] The Ath Sath Tirath, or the spot equivalent to 68 pilgrimages, is in the shade underneath the Dukh Bhanjani Ber tree. Sikh devotees, states Charles Townsend, believe that bathing in the pool near this spot delivers the same fruits as a visit to 68 pilgrimage places in India.[34]

Sikh history museums

The main ghanta ghar deori north entrance has a Sikh history museum on the first floor, according to the Sikh tradition. The display shows various paintings, of gurus and martyrs, many narrating the persecution of Sikhs over their history, as well as historical items such as swords, kartar, comb, chakkars.[59] A new underground museum near the clock tower, but outside the temple courtyard also shows Sikh history.[60][61] According to Louis E. Fenech, the display does not present the parallel traditions of Sikhism and is partly ahistorical such as a headless body continuing to fight, but a significant artwork and reflects the general trend in Sikhism of presenting their history to be one of persecution, martyrdoms and bravery in wars.[62]

The main entrance to the Gurdwara has many memorial plaques that commemorate past Sikh historical events, saints and martyrs, contributions of Ranjit Singh, as well as commemorative inscriptions of all the Sikh soldiers who died fighting in the two World Wars and the various Indo-Pakistan wars.[63]

Guru Ram Das Langar

.jpg)

Harmandir Sahib complex has a Langar, a community-run free kitchen and dining hall. It is attached to the east side of the courtyard near the Dukh Bhanjani Ber, outside of the entrance. Food is served here to all visitors who want it, regardless of faith, gender or economic background. Vegetarian food is served and all people eat together as equals. Everyone sits on the floor in rows, which is called pangat. The meal is served by volunteers as part of their kar seva ethos.[34]

Daily ceremonies

_in_Amritsar%2C_India.jpg)

There are several rites performed everyday in the Golden Temple as per the historic Sikh tradition. These rites treat the scripture as a living person, a Guru out of respect. They include:[64][65]

- Closing rite called sukhasan (sukh means "comfort or rest", asan means "position"). At night, after a series of devotional kirtans and three part ardās, the Guru Granth Sahib is closed, carried on the head, placed into and then carried in a flower decorated, pillow-bed palki (palanquin), with chanting. Its bedroom is in the Akal Takht, on the first floor. Once it arrives there, the scripture is tucked into a bed.[64][65]

- Opening rite called prakash which means "light". About dawn everyday, the Guru Granth Sahib is taken out its bedroom, carried on the head, placed and carried in a flower-decorated palki with chanting and bugle sounding across the causeway. It is brought to the sanctum. Then after ritual singing of a series of Var Asa kirtans and ardas, a random page is opened. This is the mukhwak of the day, it is read out loud, and then written out for the pilgrims to read over that day.[64][65]

Influence on contemporary era Sikhism

Singh Sabha movement

The Singh Sabha movement was a late-19th century movement within the Sikh community to rejuvenate and reform Sikhism at a time when Christian and Muslim proselytizers were actively campaigning to convert Sikhs to their religion.[66][67] The movement was triggered by the conversion of Ranjit Singh's son Duleep Singh and other well-known people to Christianity. Started in 1870s, the Singh Sabha movement's aims were to propagate the true Sikh religion, restore and reform Sikhism to bring back into the Sikh fold the apostates who had left Sikhism.[66][68][69] There were three main groups with different viewpoints and approaches, of which the Tat Khalsa group had become dominant by the early 1880s.[70][71] Before 1905, the Golden Temple had Brahmin priests, idols and images for at least a century, attracting pious Sikhs and Hindus.[72] In 1890s, these idols and practices came under attack from reformist Sikhs.[72] In 1905, with the campaign of the Tat Khalsa, these idols and images were removed from the Golden Temple.[73][74] The Singh Sabha movement brought the Khalsa back to the fore of Gurdwara administration[75] over the mahants (priests) class,[76] who had taken over control of the main gurdwaras and other institutions vacated by the Khalsa in their fight for survival against the Mughals during the 18th century[77] and had been most prominent during the 19th century.[77]

Jallianwala Bagh massacre

As per tradition, the Sikhs gathered in the Golden Temple to celebrate the festival of Baisakhi in 1919. After their visit, many walked over to the Jallianwala Bagh next to it to listen to speakers protesting Rowlatt Act and other policies of the colonial British government. A large crowd had gathered, when the British general Reginald Dyer ordered his soldiers to surround the Jallianwala Bagh, then open fire into the civilian crowd. Hundreds died and thousands were wounded.[78] The massacre strengthened the opposition to the colonial rule throughout India, particularly that from Sikhs. It triggered massive non-violent protests. The protests pressured the British government to transfer the control over the management and treasury of the Golden Temple to an elected organisation called Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC). The SGPC continues to manage the Golden Temple.[79]

Punjabi Suba movement

The Punjabi Suba movement was a long-drawn political agitation, launched by the Sikhs, demanding the creation of a Punjabi Suba, or Punjabi-speaking state, in the post-independence state of East Punjab.[80] It was first presented as a policy position in April 1948 by the Shiromani Akali Dal,[81] after the States Reorganization Commission set up after independence was not effective in the north of the country during its work to delineate states on a linguistic basis.[82] The Golden Temple complex was the main center of operations of the movement,[83] and important events during the movement that occurred at the temple included the 1955 raid by the government to quash the movement, and the subsequent Amritsar Convention in 1955 to convey Sikh sentiments to the central government.[84] The complex was also the site of speeches, demonstrations, and mass arrests,[83] and where leaders of the movement domiciled in huts during hunger strikes.[85] The borders of the modern state of Punjab, along with the official status of the state's native language of Punjabi in the Gurmukhi script, are the result of the movement, which culminated in the setting of the current borders in 1966.[86]

Operation Blue Star

The Golden Temple and Akal Takht were occupied by various militant groups in the early 1980s. These included the Dharam Yudh Morcha led by Sikh fundamentalist Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the Babbar Khalsa, the AISSF and the National Council of Khalistan.[87] In December 1983, the Sikh political party Akali Dal's President Harchand Singh Longowal had invited Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale to take up residence in Golden Temple Complex.[88] The Bhindranwale led group under military leadership of General Shabeg Singh had begun to build bunkers and observations posts in and around the Golden Temple.[89] They organised the armed militants present at the Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar in June 1984. The Golden Temple became a place for weapons training for the militants.[87] Shabeg Singh's military expertise is credited with the creation of effective defences of the Temple Complex that made the possibility of a commando operation on foot impossible. Supporters of this militant movement circulated maps showing parts of northwest India, north Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan as historic and future boundaries of the Khalsa Sikhs, with varying claims in different maps.[90] In June 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to begin Operation Blue Star against the militants.[87] The operation caused severe damage and destroyed Akal Takht. Numerous soldiers, civilians, and militants died in the crossfire. Within days of the Operation Bluestar, some 2,000 Sikh soldiers in India mutinied and attempted to reach Amritsar to liberate the Golden Temple.[87] Within six months, on 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi's Sikh bodyguards assassinated her.

In 1986, Indira Gandhi's son and the next Prime Minister of India Rajiv Gandhi ordered repairs to the Akal Takht Sahib. These repairs were removed and Sikhs rebuilt the Akal Takht Sahib in 1999.[91]

See also

- List of Gurudwaras

- List of tallest buildings in Amritsar

- Amritsar Jamnagar Expressway

- Golden Temple, Sripuram

- Gurudwara Sis Ganj Sahib

- Hazur Sahib Nanded

- Takht Sri Patna Sahib

References

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 41–42.

- Kerr, Ian J. (2011). "Harimandar". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjabi University Patiala. pp. 239–248. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2005). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 67–69, 150. ISBN 978-0-19-280601-7.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2014.

- Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, p. 33.

- Pardeep Singh Arshi 1989, pp. 5–7.

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 41-42.

- W. Owen Cole 2004, p. 7

- M. L. Runion (2017). The History of Afghanistan, 2nd Edition. Greenwood. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-313-33798-7., Quote: "Ahmad Durrani was forced to return to India and [he] declared a jihad, known as an Islamic holy war, against the Marathas. A multitude of tribes heralded the call of the holy war, which included the various Pashtun tribes, the Balochs, the Tajiks, and also the Muslim population residing in India. Led by Ahmad Durrani, the tribes joined the religious quest and returned to India (...) The domination and control of the [Afghan] empire began to loosen in 1762 when Ahmad Shah Durrani crossed Afghanistan to subdue the Sikhs, followers of an indigenous monotheistic religion of India found in the 16th century by Guru Nanak. (...) Ahmad Shah greatly desired to subdue the Sikhs, and his army attacked and gained control of the Sikh's holy city of Amritsar, where he brutally massacred thousands of Sikh followers. Not only did he viciously demolish the sacred temples and buildings, but he ordered these holy places to be covered with cow's blood as an insult and desecration of their religion (...)"

- Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 431-432.

- Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson & Paul Schellinger 2012, pp. 28-29.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2016). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0.

- Jean Marie Lafont (2002). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Lord of the Five Rivers. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 30-31.

- "Soon, Golden Temple to use phone jammers. Over Two lakh people visit the holy shrine per day for worship. In festivals over six lakh to eight lakh visit the holy shrine". The Times Of India. 19 July 2012.

- Sri Harimandir Sahib, Amritsar, Punjab, UNESCO

- Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, p. 146.

- Henry Walker 2002, pp. 95-98.

- H. S. Singha (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1.

- G.S. Mansukhani. "Encyclopaedia of Sikhism". Punjab University Patiala. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 38–40.

- Christopher Shackle & Arvind Mandair 2013, pp. xv–xvi.

- W.H. McLeod (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4.

- Christopher Shackle & Arvind Mandair 2013, pp. xv-xvi.

- Mahindara Siṅgha Joshī (1994). Guru Arjan Dev. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-81-7201-769-9.

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 42–43.

- Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, p. 67.

- Historical Dictionary of Sikhism by Louis E. Fenech, W. H. McLeod, p. 205, ISBN 978-1442236011

- State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab, by Rishi Singh, 2015 ISBN 978-9351505044 . It is, however, possible that Mian Mir, who had close links to Guru Arjan, was invited and present at the time of the laying of the foundation stone, even if he did not lay the foundation stone himself.

- State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab, by Rishi Singh, 2015 ISBN 978-9351505044

- Singh 2011, pp. 34–35.

- Dr. Madanjit Kaur “The Golden Temple: Past and Present" Dept. of Guru Nanak Studies, Guru Nanak Dev University Press, 1983, p. 11

- W. Owen Cole 2004, pp. 6–9

- Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 435–436.

- Pashaura Singh (2005), Understanding the Martyrdom of Guru Arjan Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Punjab Studies, 12(1), pp. 29–62

- W.H. McLeod (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 20 (Arjan's Death). ISBN 978-0810863446.

The Mughal rulers of Punjab were evidently concerned with the growth of the Panth, and in 1605 the Emperor Jahangir made an entry in his memoirs, the Tuzuk-i-Jahāṅgīrī, concerning Guru Arjan's support for his rebellious son Khusrau Mirza. Too many people, he wrote, were being persuaded by his teachings, and if the Guru would not become a Muslim the Panth had to be extinguished. Jahangir believed that Guru Arjan was a Hindu who pretended to be a saint and that he had been thinking of forcing Guru Arjan to convert to Islam or his false trade should be eliminated, for a long time. Mughal authorities seem to have been responsible for Arjan's death in custody in Lahore, and this may be accepted as an established fact. Whether the death was by execution, the result of torture, or drowning in the Ravi River remains unresolved. For Sikhs, Arjan is the first martyr Guru.

- Louis E. Fenech, Martyrdom in the Sikh Tradition, Oxford University Press, pp. 118–121

- Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, pp. 146–147.

- Pardeep Singh Arshi 1989, pp. 22–25.

- Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson & Paul Schellinger 2012, pp. 28–29.

- Patwant Singh (2008). Empire of the Sikhs: The Life and Times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Peter Owen. pp. 18, 177. ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- "Maharaja Ranjit Singh's contributions to Harimandir Sahib". Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "Mir Osman Ali Khan Bahadur Asaf Jah VII (1911–67)".

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2016). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0., Quote: "The Golden Temple (...) By 1776, the present structure, a harmonious blending of Mughal and Rajput (Islamic and Hindu) architectural styles was complete."

- Pardeep Singh Arshi 1989, pp. 97–116.

- Gene R. Thursby (1992). The Sikhs. Brill. pp. 14–15. ISBN 90-04-09554-3.

- Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2004). Sikhism. Infobase Publishing. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-1-4381-1779-9.

- Pardeep Singh Arshi 1989, pp. 68–73.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; Geoffrey William Bromiley (1999). The encyclopedia of Christianity (Reprint ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14596-2.

- Singh 2011, p. 80.

- Pashaura Singh; Norman Gerald Barrier; W. H. McLeod (2004). Sikhism and History. Oxford University Press. pp. 201–215. ISBN 978-0-19-566708-0.

- W. Owen Cole 2004, p. 10.

- Ian Talbot (2016). A History of Modern South Asia: Politics, States, Diasporas. Yale University Press. pp. 80–81 with Figure 8. ISBN 978-0-300-19694-8.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 435. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- Pashaura Singh; Norman Gerald Barrier (1999). Sikh Identity: Continuity and Change. Manohar. p. 264. ISBN 978-81-7304-236-2.

- Shikha Jain (2015). Yamini Narayanan (ed.). Religion and Urbanism: Reconceptualising Sustainable Cities for South Asia. Routledge. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-317-75542-5.

- H. S. Singha (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1.

- Bruce M. Sullivan (2015). Sacred Objects in Secular Spaces: Exhibiting Asian Religions in Museums. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 76–78. ISBN 978-1-4725-9083-1.

- "Golden Temple's hi-tech basement showcases Sikh history, ethos opens for pilgrims". Hindustan Times. 22 December 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Service, Tribune News. "Golden Temple's story comes alive at its plaza". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Louis E. Fenech (2000). Martyrdom in the Sikh Tradition: Playing the "game of Love". Oxford University Press. pp. 44–45, 57–61, 114–115, 157 with notes. ISBN 978-0-19-564947-5.

- K Singh (1984). The Sikh Review, Volume 32, Issues 361–372. Sikh Cultural Centre. p. 114.

- Singh 2011, pp. 81–82.

- Kristina Myrvold (2016). The Death of Sacred Texts: Ritual Disposal and Renovation of Texts in World Religions. Routledge. pp. 125–144. ISBN 978-1-317-03640-1.

- Barrier, N. Gerald; Singh, Nazer (1998). Singh, Harbans (ed.). Singh Sabha Movement (4th ed.). Patiala, Punjab, India: Punjab University, Patiala, 2002. pp. 205–212. ISBN 9788173803499. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica (2010). "Singh Sabha (Sikhism)". Encyclopædia Britannica.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair 2013, pp. 85-86.

- Louis E. Fenech & W. H. McLeod 2014, pp. 273-274.

- Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 28–29, 73–76.

- Harjot Oberoi (1994). The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in the Sikh Tradition. University of Chicago Press. pp. 382–383. ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- Kenneth W. Jones (1976). Arya Dharm: Hindu Consciousness in 19th-century Punjab. University of California Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-520-02920-0., Quote: "Brahmin priests and their idols had been associated with the Golden Temple for at least a century and had over these years received the patronage of pious Hindus and Sikhs. In the 1890s these practices came under increasing attack by reformist Sikhs."

- W. H. McLeod (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6.

- Harjot Oberoi (1994). The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in the Sikh Tradition. University of Chicago Press. pp. 320–327. ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 542–543. ISBN 978-0-19-100412-4.

- Deol, Harnik (2003). Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab. Routledge. pp. 75–78. ISBN 9781134635351.

- Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed (illustrated ed.). London, England: A&C Black. p. 83. ISBN 9781441102317. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Kristen Haar; Sewa Singh Kalsi (2009). Sikhism. Infobase Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4381-0647-2.

- Pashaura Singh & Louis E. Fenech 2014, pp. 433–434.

- Doad 1997, p. 391.

- Bal 1985, p. 419.

- Doad 1997, p. 392.

- Doad 1997, p. 397.

- Bal 1985, p. 426.

- Doad 1997, p. 398.

- Doad 1997, p. 404.

- Jugdep S Chima (2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. Sage Publications. pp. 85–95. ISBN 978-81-321-0538-1.

- Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, Volume II: 1839–2004, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 337.

- Tully, Mark (3 June 2014). "Wounds heal but another time bomb ticks away". Gunfire Over the Golden Temple. The Times of India. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Brian Keith Axel (2001). The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora". Duke University Press. pp. 96–107. ISBN 0-8223-2615-9.

- "Know facts about Harmandir Sahib, The Golden Temple". India TV. 22 June 2014.

Bibliography

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2014). "Harmandir-Sahib". Encyclopedia Britannica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kerr, Ian J. (2015). "Harimandar". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjabi University Patiala. pp. 239–248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pardeep Singh Arshi (1989). The Golden Temple: history, art, and architecture. Harman. ISBN 978-81-85151-25-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- W. Owen Cole (2004). Understanding Sikhism. Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-906716-91-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- W.H. McLeod (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-63979-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christopher Shackle; Arvind Mandair (2013). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-45101-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-100411-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-962-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Henry Walker (2002). Kerry Brown (ed.). Sikh Art and Literature. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-63136-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bal, Sarjit Singh (1985). "Punjab After Independence (1947-1956)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 46: 416–430. JSTOR 44141382. PMID 22491937.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doad, Karnail Singh (1997). Siṅgh, Harbans (ed.). Punjabi Sūbā Movement (3rd ed.). Patiala, Punjab, India: Punjab University, Patiala, 2011. pp. 391-404. ISBN 9788173803499. Retrieved 24 February 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harmandir Sahib. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Golden Temple |