Harare

Harare (/həˈrɑːreɪ/;[3] officially Salisbury until 1982)[4] is the capital and most populous city of Zimbabwe. The city proper has an area of 960.6 km2 (371 mi2) and an estimated population of 1,606,000 in 2009,[5] with 2,800,000 in its metropolitan area in 2006. Situated in north-eastern Zimbabwe in the country's Mashonaland region, Harare is a metropolitan province, which also incorporates the municipalities of Chitungwiza and Epworth.[6] The city sits on a plateau at an elevation of 1,483 metres (4,865 feet) above sea level and its climate falls into the subtropical highland category.

Harare | |

|---|---|

City and Province | |

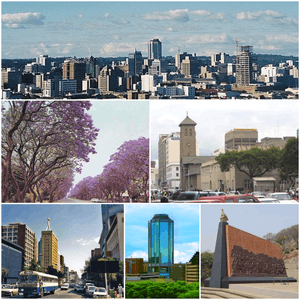

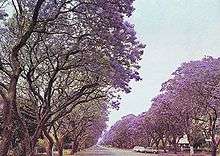

Clockwise, from top: Harare skyline; Parliament of Zimbabwe (front) and the Anglican Cathedral (behind); Heroes Acre monument; New Reserve Bank Tower; downtown Harare; Jacaranda trees lining Josiah Chinamano Avenue | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: Sunshine City, H Town | |

Motto(s):

| |

Location of Harare Province in Zimbabwe | |

| Coordinates: 17°49′45″S 31°3′8″E | |

| Country | Zimbabwe |

| Province | Harare |

| Founded | 1890 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1935 |

| Renamed Harare | 1982 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Herbert Gomba[1] |

| Area | |

| • City and Province | 960.6 km2 (370.9 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,490 m (4,890 ft) |

| Population (2013) | |

| • City and Province | 1,606,000 |

| • Density | 2,540/km2 (4,330/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,619,000[2] |

| Demonym(s) | Hararean |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Area code(s) | 242 |

| Climate | Cwb |

| Website | hararecity |

| Dialling code 242 (or 0242 from within Zimbabwe) | |

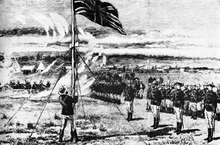

The city was founded in 1890 by the Pioneer Column, a small military force of the British South Africa Company, and named Fort Salisbury after the UK Prime Minister Lord Salisbury. Company administrators demarcated the city and ran it until Southern Rhodesia achieved responsible government in 1923. Salisbury was thereafter the seat of the Southern Rhodesian (later Rhodesian) government and, between 1953–63, the capital of the Central African Federation. It retained the name Salisbury until 1982, when it was renamed Harare on the second anniversary of Zimbabwean independence from the United Kingdom.

History

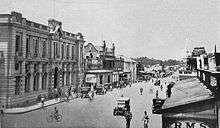

The Pioneer Column, a military volunteer force of settlers organised by Cecil Rhodes, founded the city on 12 September 1890 as a fort.[7][8] They originally named the city Fort Salisbury after The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, then-Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and it subsequently became known simply as Salisbury. The Salisbury Polo Club was formed in 1896.[9] It was declared to be a municipality in 1897 and it became a city in 1935.[10]

The area at the time of founding of the city was poorly drained and earliest development was on sloping ground along the left bank of a stream that is now the course of a trunk road (Julius Nyerere Way). The first area to be fully drained was near the head of the stream and was named Causeway as a result. This area is now the site of many of the most important government buildings, including the Senate House and the Office of the Prime Minister, now renamed for the use of the President after the position was abolished in January 1988.[11]

Salisbury was the capital of the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia from 1923, and of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland from 1953–63. Ian Smith's Rhodesian Front government declared Rhodesia independent from the United Kingdom on 11 November 1965, and proclaimed the Republic of Rhodesia in 1970. Subsequently, the nation became the short-lived state of Zimbabwe Rhodesia, it was not until 18 April 1980 that the country was internationally recognised as independent as the Republic of Zimbabwe.

Post-independence (1980–98)

The name of the city was changed to Harare on 18 April 1982, the second anniversary of Zimbabwean independence, taking its name from the village near Harare Kopje of the Shona chief Neharawa, whose nickname was "he who does not sleep".[12] Prior to independence, "Harare" was the name of the black residential area now known as Mbare.

Economic difficulties and hyperinflation (1999–2008)

In the early twenty-first century, Harare has been adversely affected by the political and economic crisis that is currently plaguing Zimbabwe, after the contested 2002 presidential election and 2005 parliamentary elections. The elected council was replaced by a government-appointed commission for alleged inefficiency, but essential services such as rubbish collection and street repairs have rapidly worsened, and are now virtually non-existent. In May 2006, the Zimbabwean newspaper the Financial Gazette, described the city in an editorial as a "sunshine city-turned-sewage farm".[13] In 2009, Harare was voted to be the toughest city to live in according to the Economist Intelligence Unit's livability poll.[14] The situation was unchanged in 2011, according to the same poll, which is based on stability, healthcare, culture and environment, education, and infrastructure.[15]

Operation Murambatsvina

In May 2005, the Zimbabwean government demolished shanties and backyard cottages in Harare, Epworth and the other cities in the country in Operation Murambatsvina[16] ("Drive Out Trash"). It was widely alleged that the true purpose of the campaign was to punish the urban poor for supporting the opposition Movement for Democratic Change and to reduce the likelihood of mass action against the government by driving people out of the cities. The government claimed it was necessitated by a rise of criminality and disease. This was followed by Operation Garikayi/Hlalani Kuhle (Operation "Better Living") a year later which consisted of building concrete housing of poor quality..

2009–present

In late-March 2010, Harare's Joina City Tower was finally opened after fourteen years of delayed construction, marketed as Harare's new Pride.[17] Initially, uptake of space in the tower was low, with office occupancy at only 3% in October 2011.[18] By May 2013, office occupancy had risen to around half, with all the retail space occupied.[19]

The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Harare as the world's least liveable city out of 140 surveyed in February 2011,[20] rising to 137th out of 140 in August 2012.[21] In 2018, the Harare was ranked 137 out of the 140 surveyed cities by The Economist Intelligence Unit's Global Liveability Ranking, making it the World's sixth least liveable city.[22]

Future plans

During late-2012, plans to build a new capital district in Mt. Hampden, about twenty kilometres (12 miles) north-west of Harare's central business district, were announced and illustrations shown in Harare's daily newspapers. The location of this new district would imply an expansion into Zvimba District. The plan generated varied opinions.[23]

In March 2015, Harare City Council planned a two-year project to install 4,000 solar street lights, at a cost of $15,000,000 starting in the central business district.[24]

In November 2017, the biggest demonstration in the history of the Republic of Zimbabwe was held in Harare which led to the forced resignation of the long-serving 93-year-old President of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe an event which was part of the first successful coup in Zimbabwe.[25][26]

Geography

Topography

The city sits on one of the higher parts of the Highveld plateau of Zimbabwe at an elevation of 1,483 metres (4,865 feet). The original landscape could be described as a "parkland".[27]

Suburbs

The Northern and North Eastern suburbs of Harare are home to the more affluent population of the city including former president Robert Mugabe who lived in Borrowdale Brooke.[28] These northern suburbs are often referred to as 'dales' because of the common suffix -dale found in some suburbs such as Avondale, Greendale and Borrowdale. The dwellings are mostly low density homes of 3 bedrooms or more and these usually are occupied by families.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Harare has a subtropical highland climate (Köppen Cwb), an oceanic climate variety. Because the city is situated on a plateau, its high altitude and cool south-easterly airflow cause it to have a climate that is cooler and drier than a tropical or subtropical climate.

The average annual temperature is 17.95 °C (64.3 °F), rather low for the tropics. This is due to its high altitude position and the prevalence of a cool south-easterly airflow.[29]

There are three main seasons: a warm, wet season from November to March/April; a cool, dry season from May to August (corresponding to winter in the Southern Hemisphere); and a hot, dry season in September/October. Daily temperature ranges are about 7–22 °C (45–72 °F) in July (the coldest month), about 15–29 °C (59–84 °F) in October (the hottest month) and about 16–26 °C (61–79 °F) in January (midsummer). The hottest year on record was 1914 with 19.73 °C (67.5 °F) and the coldest year was 1965 with 17.13 °C (62.8 °F).

The average annual rainfall is about 825 mm (32.5 in) in the southwest, rising to 855 mm (33.7 in) on the higher land of the northeast (from around Borrowdale to Glen Lorne). Very little rain typically falls during the period May to September, although sporadic showers occur most years. Rainfall varies a great deal from year to year and follows cycles of wet and dry periods from 7 to 10 years long. Records begin in October 1890 but all three Harare stations stopped reporting in early 2004.[30]

The climate supports a natural vegetation of open woodland. The most common tree of the local region is the Msasa Brachystegia spiciformis that colours the landscape wine red with its new leaves in late August. Two introduced species of trees, the jacaranda and the flamboyant from South America and Madagascar respectively, which were introduced during the colonial era, contribute to the city's colour palette with streets lined with either the lilac blossoms of the jacaranda or the flame red blooms from the flamboyant. They flower in October/November and are planted on alternative streets in the capital. Also prevalent is bougainvillea.

| Climate data for Harare (1961–1990, extremes 1897–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.9 (93.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

33.5 (92.3) |

36.7 (98.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26.2 (79.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.3 (48.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.7 (40.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 190.8 (7.51) |

176.3 (6.94) |

99.1 (3.90) |

37.2 (1.46) |

7.4 (0.29) |

1.8 (0.07) |

2.3 (0.09) |

2.9 (0.11) |

6.5 (0.26) |

40.4 (1.59) |

93.2 (3.67) |

182.7 (7.19) |

840.6 (33.09) |

| Average precipitation days | 17 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 82 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 77 | 72 | 67 | 62 | 60 | 55 | 50 | 45 | 48 | 63 | 73 | 62 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 217.0 | 190.4 | 232.5 | 249.0 | 269.7 | 264.0 | 279.0 | 300.7 | 294.0 | 285.2 | 231.0 | 198.4 | 3,010.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.0 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 8.2 |

| Source #1: World Meteorological Organization,[31] NOAA (sun and mean temperature, 1961–1990),[32] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity, 1954–1975),[33] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[34] | |||||||||||||

International venue

Harare has been the location of several international summits such as the 8th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement (6 September 1986) and Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 1991.[35] The latter produced the Harare Declaration, dictating the membership criteria of the Commonwealth. In 1998, Harare was the host city of the 8th Assembly of the World Council of Churches.[36]

In 1995, Harare hosted most of the 6th All-Africa Games, sharing the event with other Zimbabwean cities such as Bulawayo and Chitungwiza. It has hosted some of the matches of 2003 Cricket World Cup which was hosted jointly by Kenya, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Several of the matches were also held in Bulawayo. Harare also hosted the ICC Cricket 2018 World Cup Qualifier matches in March 2018.[37]

The city is also the site of one of the Harare International Festival of the Arts (HIFA), which has featured such acclaimed artists as Cape Verdean singer Sara Tavares.[38]

Reality TV shows shot in Harare include Battle of the Chefs: Harare, which was screened by the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation.

Economy

Harare is Zimbabwe's leading financial, commercial, and communications centre, as well as a trade centre for tobacco, maize, cotton, and citrus fruits. Manufacturing, including textiles, steel, and chemicals, are also economically significant, as is local gold mining.

Transport

The public transport system within the city includes both public and private sector operations. The former consist of ZUPCO buses and National Railways of Zimbabwe commuter trains. Privately owned public transport comprised licensed station wagons, nicknamed emergency taxis until 1993, when the government began to replace them with licensed buses and minibuses, referred to officially as commuter omnibuses.[39]

The National Railways of Zimbabwe operates a daily overnight passenger train service that runs from Harare to Mutare and another one from Harare to Bulawayo, using the Beira–Bulawayo railway.[40] Harare is linked by long-distance bus services to most parts of Zimbabwe.

The city is crossed by Transafican Highway 9 (TAH 9), which connects it to the cities of Lusaka and Beira.

The largest airport of the country, the Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport, serves Harare.

Education

The University of Zimbabwe was founded in 1952, the country's oldest university, is located in Harare, as are several other colleges and universities.

Sports

Football is most popular among the people of Harare. Harare is home to Harare Sports Club ground. It has hosted many Test, One Day Internationals and T20I Cricket matches. Harare is also home to the Zimbabwe Premier Soccer League clubs Dynamos F.C., Harare City, Black Rhinos F.C. and CAPS United F.C..[41] The main stadiums are National Sports Stadium and Rufaro Stadium.

Media

Residents are exposed to a variety of sources for information. In the print media, there is the Herald, Financial Gazette, Zimbabwe Independent, Standard, NewsDay, H-Metro, Daily News and Kwayedza. Online media outlets include ZimOnline, ZimDaily, Guardian, NewZimbabwe, Times, Harare Tribune, Zimbabwe Metro, The Zimbabwean, The Zimbabwe Mail.

Television

The state-owned ZBC TV is the only free to air TV channel in the city.[42] The majority of the households rely on the South African-based satellite television distributor, DStv for better entertainment, news and sport across Africa and the world.

Notable institutions

- 44 Harvest House

- Eastgate Centre

- Econet Wireless

- Gwanzura

- Joina City

- Mbare Musika

- Parirenyatwa Hospital

- Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe

- Sam Nujoma Street

- Zimbabwe Stock Exchange

Culture

- National Gallery of Zimbabwe

- Heroes Acre

- Zimbabwe Museum of Human Sciences

Places of worship

Among the places of worship, they are predominantly Christian churches and temples : Assemblies of God, Baptist Convention of Zimbabwe (Baptist World Alliance), Reformed Church in Zimbabwe (World Communion of Reformed Churches), Church of the Province of Central Africa (Anglican Communion), Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Harare (Catholic Church).[43]

International relations

Harare has co-operation agreements and partnerships with the following towns:[44]

Gallery

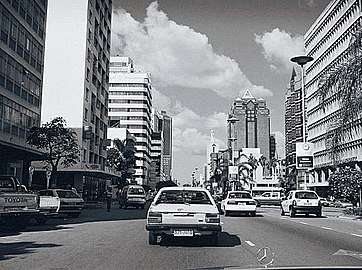

Sam Nujoma Street, view south

Sam Nujoma Street, view south- Anglican Cathedral of St Mary and All Saints

Downtown Harare, Reserve Bank ahead

Downtown Harare, Reserve Bank ahead First Street

First Street Along parliament buildings

Along parliament buildings Harare Central Station

Harare Central Station Eastgate centre

Eastgate centre.jpg) Relief at National Heroes Acre

Relief at National Heroes Acre.jpg) National Heroes Acre

National Heroes Acre

See also

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Harare. |

- Districts of Zimbabwe

- Place names in Zimbabwe

- Provinces of Zimbabwe

- Suburbs of Harare

References

- "Mayor 2013–2018". City of Harare. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- "Demographia World Urban Areas PDF (March 2013)" (PDF). Demographia. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Harare". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Names (Alteration) Act Chapter 10:14 Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency".

- Harare Provincial Profile (PDF) (Report). Parliament Research Department. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- Hoste, Skipper (1977). N.S.Davies (ed.). Gold Fever. Salisbury, Rhodesia: Pioneer Head. ISBN 0-86918-013-4.

- Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 120

- Horace A. Laffaye, Polo in Britain: A History, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012, p. 76

- Britannica, Harare, britannica.com, USA, accessed on July 7, 2019

- Journal of Frederick Courtney Selous, Rhodesiana Reprint Library, Salisbury, 1969

- Room, Adrian (2003). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for Over 5000 Natural Features, Countries, Capitals, Territories, Cities and Historic Sights. McFarland. ISBN 9780786418145.

- kdc. "The Zimbabwe Situation". zimbabwesituation.com.

- Agence France-Presse. "Vancouver world's easiest city to live in, Harare worst: Poll". The Vancouver Sun. Calgary Herald. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "Least livable cities". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- "Zimbabwe - Rhodesia and the UDI".

- "Joina City- Harare's New Pride – Inside Joina City- Facts & Figures". Urbika.com. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Joina City Occupancy 3pc". ForBuilder. 16 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013.

- Moyo, Jason (31 May 2013). "Zimbabwe's Changing Spaces". Mail and Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Koranyi, Balazs (21 February 2011). "Vancouver still world's most livable city: survey". Reuters. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- The Economist Intelligence Unit (August 2012). Liveabililty Ranking and Overview August 2012 (Report). Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "The Global Liveability Index 2018" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit.

- "Zvimba paradise city revealed". Newsday. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Madalitso Mwando (27 March 2015). "Zimbabwe Capital Turns to Solar Streetlights to Cut Costs, Crime". allAfrica.com – Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Zimbabwe crowds rejoice as they demand end to Mugabe rule". BBC News.

- "Zimbabwe leader Mugabe under house arrest as army tightens grip on capital". Market Watch.

- TV Bulpin: Discovering South Africa pp 838

- "Mugabe's Borrowdale Brooke neighbour speaks out". 22 June 2014.

- Average for years 1965–1995, Goddard Institute of Space Studies World Climate database

- Global Historic Climate Network database NGDC

- "World Weather Information Service – Harare". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Harare Kutsaga Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Klimatafel von Harare-Kutsaga (Salisbury) / Simbabwe" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Station Harare" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "List of previous CHOGMS". Archived from the original on 31 October 2008.

- "8th assembly & 50th anniversary". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "ICC World Cup Qualifiers 2018 - Super Sixes Match 8 - Zimbabwe v United Arab Emirates - Preview".

- "What's Next..." reflecting a sense of positive progress". hifa.co.zw. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- D.A.C. Maunder and T.C. Mbara, "The initial effects of introducing commuter omnibus services in Harare, Zimbabwe", TRL: The Future of Transport 123 (January 1995). ISBN 1-84608-122-X; and https://trl.co.uk/reports/TRL123

- Mlambo, Alois (2003). "Bulawayo, Zimbabwe". In Paul Tiyambe Zeleza; Dickson Eyoh (eds.). Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century African History. Routledge. ISBN 0415234794.

- "'Harare among world's worst cities to live in'". DailyNews Live. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- 'MuckRaker: ZBC has taken over the RBC's mantle', Zimbabwe Independent, 16 February 2012

- Britannica, Zimbabwe, britannica.com, USA, accessed on July 7, 2019

- Dhedheya, Itai. "City of Harare - Twinning Arrangements". City of Harare. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- Pennick, Faith; Calhoun, Jim (5 August 1990). "Harare newest link: Cincinnati adds sister city in Africa". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Harare twins Guangzhou". The Herald. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Kalayil, Sheena (2 April 2015). The Beloved Country. Grosvenor House Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 9781781484647.

Bibliography

External links