Gujarati people

The Gujarati people or Gujaratis are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group native to Gujarat who speak Gujarati, an Indo-Aryan language. Gujaratis are prominent entrepreneurs and industrialists, and many notable Indian independence activists were Gujarati.[15][16][17][18]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 60 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 55,492,554[2] | |

| 1,000,000–3,000,000[3][4] | |

| 500,000–1,700,000[5][6][7] | |

| 600,000[8] | |

| 285,000[9] | |

| 122,460[10] | |

| 52,888[11] | |

| 34,900[12] | |

| 30,000[13] | |

| 26,622[14] | |

| Languages | |

| Gujarati | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Minority: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryan peoples | |

Geographical locations

Despite significant migration primarily for economic reasons, most Gujaratis in India live in the state of Gujarat in western India.[19] Gujaratis also form a significant part of the populations in the neighboring metropolis of Mumbai and union territoy of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu, which was a former Portuguese colony.[20] There are very large Gujarati immigrant communities in other parts of India, most notably in Mumbai,[21] Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Bangalore[22] and other cities like Kochi.[23][24] All throughout history[25] Gujaratis have earned a reputation as being India's greatest merchants,[26][27][28]industrialists and business entrepreneurs,[29] and have therefore been at forefront of migrations all over the world, particularly to regions that were part of the British empire such as Fiji, Hong Kong, New Zealand, East Africa and countries in Southern Africa.[30] Diasporas and transnational networks in many of these countries date back to more than a century.[31][32] In recent decades, larger numbers of Gujaratis have migrated to English speaking countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and the United States.[33][34]

History

In 1790-1, an epidemic devastated numerous parts of Gujarat during which 100,000 Gujaratis were killed in Surat alone.[35]

An outbreak of bubonic plague in 1812 has been claimed to have killed about half the Gujarati population.[36]

Early European travelers like Ludovico di Varthema (15th century) traveled to Gujarat and wrote on the people of Gujarat. He noted that Jainism had a strong presence in Gujarat and opined that Gujaratis were deprived of their kingdom by Mughals because of their kind heartedness. His description of Gujaratis was:[37]

...a certain race which eats nothing that has blood, never kills any living things... and these people are neither moors nor heathens... if they were baptized, they would all be saved by the virtue of their works, for they never do to others what they would not do unto them.

Social stratification

Orthodox Gujarati society, which was mercantile by nature,[38] was historically organized along ethno-religious lines and shaped into existence on the strength of its Mahajan ("guild assemblies"),[39][40] and for its institution of Nagarsheth ("head of the guild assembly"); a 16th-century Mughal system akin to medieval European guilds which self-regulated the mercantile affairs of multi-ethnic, multi-religious communities in the Gujarati bourgeoisie long before municipal state politics was introduced.[41][42] Historically, Gujaratis belonging to numerous faiths and castes, thrived in an inclusive climate surcharged by a degree of cultural syncretism, in which Hindus and Jains dominated occupations such as shroffs and brokers whereas, Muslims, Hindus and Parsis largely dominated sea shipping trade. This led to religious interdependence, tolerance, assimilation and community cohesion ultimately becoming the hallmark of modern-day Gujarati society.[43][44][45]

Religion

The Gujarati people are predominantly Hindu. There is also a significant populations of Muslims, and minor populations of Buddhists, Zoroastrians, Jews, Jains, Christians, and Bahá’ís.[46][47][48]

Hindu communities

The major communities in Gujarat are the major sailor and seafood exporters Kharwa, traditional Agriculturalist such as Patel, Bharvad, and Rabari, Artisan communities (Gurjar, Prajapati, Sindhi Mochi), Brahmin communities (such as Joshi, Anavil, Nagar, Modh), Farming communities (such as Choudhary Jats and Koli people, Genealogist communities (such as Charans and Barots), Kshatriya communities (such as Koli Thakor[49], Banushali, Kathi Darbars, Karadia, Nadoda, Dabhi, Chudasama, Ahir, Lohana, Maher), Parsi Community, Tribal communities (such as Bhils, Meghwal and Kolis),Vaishya (such as Bhatia, Soni) and Devipujak (such as Dataniya, Dantani, Chunara, Patni).

Muslim communities

The major Gujarati Muslim communities include Nizari Ismailis, Bhadala, Daudi Bohra, Memon, Khoja, Sayyid, Siddhi, Patni Jamat and Vahora.

Diaspora

Gujaratis have a long tradition of seafaring and a history of overseas migration to foreign lands, to Yemen[50] Oman[51] Bahrain,[52] Kuwait, Zanzibar[53] and other countries in the Persian Gulf[54] since a mercantile culture resulted naturally from the state's proximity to the Arabian Sea.[55] The countries with the largest Gujarati populations are Pakistan, United Kingdom, United States, Canada and many countries in Southern and East Africa.[56] Globally, Gujaratis are estimated to comprise around 33% of the Indian diaspora worldwide and can be found in 129 of 190 countries listed as sovereign nations by the United Nations.[57] Non Resident Gujaratis (NRGs) maintain active links with the homeland in the form of business, remittance, philanthropy, and through their political contribution to state governed domestic affairs.[58][59][60]

Gujarati parents in the diaspora are not comfortable with the possibility of their language not surviving them.[61] In a study, 80% of Malayali parents felt that "children would be better off with English", compared to 36% of Kannada parents and only 19% of Gujarati parents.[61]

Pakistan

.jpg)

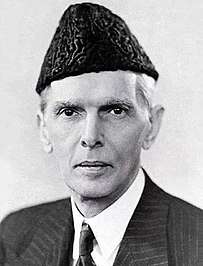

There is a community of Gujarati Muslims mainly settled in the Pakistani province of Sindh for generations. Community leaders say there are 3,000,000 speakers of Gujarati language in Karachi.[4] A sizable number migrated after the Partition of India and subsequent creation of independent Pakistan in 1947. These Pakistani Gujaratis belong mainly to the Ismāʿīlī, Khoja, Dawoodi Bohra, Chundrigar, Charotar Sunni Vohra, khatri Muslims Kutchi Memons and Khatiawari Memons; however, many Gujaratis are also a part of Pakistan's small but vibrant Hindu community.[62] Famous Gujaratis of Pakistan include Muhammed Ali Jinnah (father of Pakistan), Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar (sixth Prime Minister of Pakistan), Sir Adamjee Haji Dawood (philanthropist), Abu Bakr Osman Mitha (Major-General), Abdul Razzak Yaqoob (philanthropist), Javed Miandad (Pakistani cricketer),[63] Abdul Sattar Edhi (humanitarian), Jehangir H. Kothari (philanthropist),[64] Abdul Gaffar Billoo (philanthropist), Sarfraz Ahmed(Pakistani cricketer), Ramzan Chhipa (philanthropist), Tapu Javeri (Pakistani fashion and art photographer), Pervez Hoodbhoy (Pakistani nuclear physicist)[65] and Ardeshir Cowasjee (Pakistani critic and social activist).[66]

Sri Lanka

Main article: Gujarati Muslims in Sri Lanka

There is relatively a large number of Gujarati Muslims settled in Sri Lanka. They mainly represent the Dawoodi Bhora and the Memon community, and there is also a minority of Sindhi people in Sri Lanka. These communities are mainly into trading businesses and lately, they have diversified into different trades and sectors. Gujarati Muslims started their trading route between India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in the late 1880s. Great number of Gujarati Muslims migrated after the Partition of India in 1947. These communities are well known for their social welfare activities in Sri Lanka. In addition, Gujarati Muslims have shown their excellence in business and various trades by developing large enterprises in Sri Lanka. Few of them are: Expolanka, Brandix, Amana Bank of Sri Lanka, Adam Group, Akbar Tea, Timex Garments, and Abans Group. Members of these community maintain their Indian Gujarati culture in their every day life. Bhoras speak the Gujarati language and follow the Shia Islam and the Memon people speak the Memon language and they follow the Sunni Hanafi Islam.

United States

The United States has the second-largest Gujarati diaspora after Pakistan. The highest concentration of the population of over 100,000 is in the New York City Metropolitan Area alone, notably in the growing Gujarati diasporic center of India Square in Jersey City, New Jersey, and Edison in Middlesex County in Central New Jersey. Significant immigration from India to the United States started after the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.[71][72] Early immigrants after 1965 were highly educated professionals. Since US immigration laws allow sponsoring immigration of parents, children and particularly siblings on the basis of family reunion, the numbers rapidly swelled.[73] A number of Gujarati are twice or thrice-migrant because they came directly from the former British colonies of East Africa or from East Africa via Great Britain respectively[74] Given the Gujarati propensity for business enterprise, a number of them opened shops and motels. Now in the 21st century over 40% of the hospitality industry in the United States is controlled by Gujaratis.[75][76][77] Gujaratis, especially the Patidar samaj, also dominate as franchisees of fast food restaurant chains such as Subway and Dunkin' Donuts.[78] The descendants of the Gujarati immigrant generation have also made high levels of advancement into professional fields, including as physicians, engineers and politicians. In August 2016, Air India commenced single aircraft (no transfer) flight service between Ahmedabad and Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey, via London Heathrow International Airport.[79]

Notable Gujarati Americans include Ami Bera (United States Congress),[80] Reshma Saujani (American politician),[81] Sonal Shah (economist to Whitehouse),[82] Raj Shah (White House Deputy Press Secretary under President Trump),[83] Rohit Vyas (Indian American journalist), Bharat Desai (CEO Syntel),[84] Vyomesh Joshi (Forbes),[85] Romesh Wadhwani (Forbes),[86][87] Raj Bhavsar (sports)[88] Halim Dhanidina (first Muslim judge of California), Savan Kotecha (Grammy nominated American songwriter),[89] and Hollywood actresses, Sheetal Sheth[90] and Noureen DeWulf.[91]

Europe

United Kingdom

Gujaratis have had a long involvement with Britain. The original East India Company set up a factory (trading post) in the port city of Surat in Gujarat in 1615. These were the beginnings of first real British involvement with India that eventually led to the formation of the British Raj. The third largest overseas diaspora of Gujaratis, after Pakistan and United States, is in the United Kingdom. At a population of around 600,000[8] Gujaratis form almost half of the Indian community who live in the UK (1.2 million). Gujaratis first went to the UK in the 19th century with the establishment of the British Raj in India. Prominent members of this community such as Shyamji Krishna Varma played a vital role in exerting political pressure upon colonial powers during the Indian independence movement.

The present day Gujarati diaspora in the UK is mostly the second and third generation descendants of "twice-over" immigrants from the former British colonies of East Africa, Portugal, and Indian Ocean Islands. Most of them despite being British Subjects had restricted access to Britain after successive Immigration acts of 1962, 1968 and 1971. Most were, however, eventually admitted on the basis of a Quota voucher system or, in case of Uganda, as refugees after the expulsion order by the Ugandan ruler, Idi Amin in August 1972.

Gujaratis in Britain are regarded as affluent middle-class peoples who have assimilated into the milieu of British society.[92][93] They are celebrated for revolutionizing the corner shop, and energising the British economy which changed Britain's antiquated retail laws forever.[94][95][96] Demographically, Hindus form a majority along with a significant number of Jains and Muslims,[97] and smaller numbers of Gujarati Christians.[98] They are predominantly settled in metropolitan areas like Greater London, East Midlands, West Midlands, Lancashire and Yorkshire.[8] Cities with significant Gujarati populations include Leicester and London boroughs of Brent, Barnet, Harrow and Wembley. There is also a small, but vibrant Gujarati-speaking Parsi community of Zoroastrians present in the country, dating back to the bygone era of Dadabhai Navroji, Shapurji Saklatvala and Pherozeshah Mehta.[99] Both Hindus and Muslims have established caste or community associations, temples, and mosques to cater for the needs of their respective communities. A well known temple popular with Gujaratis is the BAPS Swaminarayan Temple in Neasdon, London. A popular mosque that caters for the Gujarati Muslim community in Leicester is the Masjid Umar. Leicester has a Jain Temple that is also the headquarters of Jain Samaj Europe.[100] The Shree Prajapati Association is a charity, already thriving in East Africa, which has 13 branches in the U.K. and is strongly dependent on support from the Gujarati community in Britain.

Gujarati Hindus in the UK have maintained many traditions from their homeland. The community remains religious with more than 100 temples catering for their religious needs. All major Hindu festivals such as Navratri, Dassara, and Diwali are celebrated with a lot of enthusiasm even from the generations brought up in UK. Gujarati Hindus also maintain their caste affiliation to some extent with most major castes having their own community association in each population center with significant Gujarati population such as Leicester and London suburbs. Patidars form the largest community in the diaspora including Kutch Leva Patels,[101] followed closely by Lohanas of Saurashtra origin.[102] Gujarati Rajputs from various regional backgrounds are affiliated with several independent British organizations dependent on caste such as Shree Maher Samaj UK,[103] and the Gujarati Arya Kshatriya Mahasabha-UK.[104]

Endogamy remains important to Gujarati Muslims in UK with the existence of matrimonial services specifically dedicated to their community.[105] Gujarati Muslim society in the UK have kept the custom of Jamat Bandi, literally meaning communal solidarity. This system is the traditional expression of communal solidarity. It is designed to regulate the affairs of the community and apply sanctions against infractions of the communal code. Gujarati Muslim communities, such as the Ismāʿīlī, Khoja, Dawoodi Bohra, Sunni Bohra, and Memon have caste associations, known as jamats that run mosques and community centers for their respective communities.

India becoming the predominant IT powerhouse in the 1990s has led to waves of new immigration by Gujaratis, and other Indians with software skills to the UK.

In 2005, the Gujarat Studies Association was formed in order to raise awareness about research being conducted on the Gujaratis - their patron is Lord Bhikhu Parekh.

Belgium

Two Gujarati business communities, the Palanpuri Jains and the Kathiawadi Patels from Surat, have come to dominate the diamond industry of Belgium.[106] They have largely displaced the Orthodox Jewish community which previously dominated this industry in Belgium.[107]

Canada

Canada, just like its southern neighbour, is home to a large Gujarati community. According to the 2016 census, there are 122,460 Gujaratis of various religious backgrounds living in Canada.[108] The majority of them live in Toronto and its suburbs - home to the second largest Gujarati community in North America, after the New York Metropolitan Area. Gujarati Hindus are the second largest linguistic/religious group in Canada's Indian community after Punjabi Sikhs, and Toronto is home to the largest Navratri raas garba festival in North America.[109] The Ismaili Khoja form a significant part of the Canadian diaspora estimated to be about 80,000 in numbers overall.[110] Most of them arrived in Canada in the 1970s as immigrants from Uganda and other countries of East Africa.[111][112]

Notable Gujarati Canadians include Bharat Masrani (CEO of TD Bank Group),[113] Zain Verjee (CNN journalist),[114] Ali Velshi (former CNN, current MSNBC journalist),[115] Rizwan Manji (Canadian actor), Avan Jogia (Canadian actor[116]), Richie Mehta (Canadian film director), Nazneen Contractor (Canadian actress), Ishu Patel (BAFTA-winning Animations director), Arif Virani (Member of Parliament for Parkdale-High Park),[117] Rahim Jaffer (Member of Parliament for Edmonton-Strathcona),[118] Naheed Nenshi (36th Mayor of Calgary),[119] Omar Sachedina (CTV News anchor)[120] and Prashant Pathak (Investor and Philanthropist).[121]

East Africa

Former British colonies in East Africa had many residents of South Asian descent. The primary immigration was mainly from Gujarat and to a lesser extent from Punjab. They were brought there by the British Empire from India to do clerical work in Imperial service, or unskilled and semi-skilled manual labour such as construction or farm work. In the 1890s, 32,000 labourers from British India were brought to the then British East African colonies under indentured labour contracts to work on the construction of the Uganda Railway that started in the Kenyan port city of Mombasa and ended in Kisumu on Kenyan side of Lake Victoria. Most of the surviving Indians returned home, but 6,724 individuals decided to remain in the African Great Lakes after the line's completion.

Many Asians, particularly the Gujarati, in these regions were in the trading businesses. They included Gujaratis of all religions as well many of the castes and Quoms. Since the representation of Indians in these occupations was high, stereotyping of Indians in Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyka as shopkeepers was common. A number of people worked for the British run banks. They also worked in skilled labor occupations, as managers, teachers and administrators. Gujarati and other South Asians had significant influence on the economy, constituting 1% of the population while receiving a fifth of the national income. For example, in Uganda, the Mehta and Madhvani families controlled the bulk of the manufacturing businesses. Gated ethnic communities served elite healthcare and schooling services. Additionally, the tariff system in Uganda had historically been oriented toward the economic interests of South Asian traders.[122] One of the oldest Jain overseas diaspora was of Gujarat. Their number was estimated at 45,000 at the independence of the East African countries in the early 1960s.[123] Most members of this community belonged to Gujarati speaking Halari Visa Oshwal Jain community originally from the Jamnagar area of Saurashtra.[123][124]

The countries of East Africa gained independence from Britain in the early 1960s. At that time most Gujarati and other Asians opted to remain as British Subjects. The African politicians at that time accused Asians of economic exploitation and introduced a policy of Africanization. The 1968 Committee on "Africanisation in Commerce and Industry" in Uganda made far-reaching Indophobic proposals. A system of work permits and trade licenses was introduced in 1969 to restrict the role of Indians in economic and professional activities. Indians were segregated and discriminated against in all walks of life.[125] During the middle of the 1960s many Asians saw the writing on the wall and started moving either to UK or India. However, restrictive British immigration policies stopped a mass exodus of East African Asians until Idi Amin came to power in 1971. He exploited pre-existing Indophobia and spread propaganda against Indians involving stereotyping and scapegoating the Indian minority. Indians were stereotyped as "only traders" and "inbred" to their profession. Indians were labelled as "dukawallas" (an occupational term that degenerated into an anti-Indian slur during Amin's time), and stereotyped as "greedy, conniving", without any racial identity or loyalty but "always cheating, conspiring and plotting" to subvert Uganda. Amin used this propaganda to justify a campaign of "de-Indianization", eventually resulting in the expulsion and ethnic cleansing of Uganda's Indian minority.[125]

Kenya

Gujarati and other Indians started moving to the Kenya colony at the end of the 19th century when the British colonial authorities started opening up the country with the laying down of the railroads. A small colony of merchants, however, had existed on the port cities such Mombasa on the Kenyan coast for hundreds of years prior to that.[126] The immigrants who arrived with the British were the first ones to open up businesses in rural Kenya a century ago. These Dukawalas or shopkeepers were mainly Gujarati (Mostly Jains and Hindus and a minority of Muslims). Over the following decades the population, mainly Gujarati but also a sizable number of Punjabi, increased in size. The population started declining after the independence of Kenya in the 1960s. At that time the majority of Gujaratis opted for British citizenship and eventually moved there, especially to cities like Leicester or London suburbs. Famous Kenyans of Gujarati heritage who contributed greatly to the development of East Africa include Thakkar Bapa, Manu Chandaria,[127] Atul Shah, Baloobhai Patel,[128] Bhimji Depar Shah (Forbes),[129] Naushad Merali (Forbes),[130] and Indian philanthropist, Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee,[131] who played a large role in the development of modern-day Kenya during colonial rule.[132][133]

Uganda

There is a small community of people of Indian origin living in Uganda, but the community is far smaller than before 1972 when Ugandan ruler Idi Amin expelled most Asians, including Gujaratis.[134] In the late 19th century, mostly Sikhs, were brought on three-year contracts, with the aid of Imperial British contractor Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee to build the Uganda Railway from Mombasa to Kisumu by 1901, and to Kampala by 1931. Some died, while others returned to India after the end of their contracts, but few chose to stay. They were joined by Gujarati traders called "passenger Indians",[135] both Hindu and Muslim free migrants who came to serve the economic needs of the indentured labourers, and to capitalise on the economic opportunities.

After the 1972 expulsion, most Indians and Gujaratis migrated to the United Kingdom. Due to the efforts of the Aga Khan, many Khoja Nizari Ismaili refugees from Uganda were offered asylum in Canada.[136]

Tanzania

Indians have a long history in Tanzania starting with the arrival of Gujarati traders in the 19th century.[137] There are currently over 50,000 people of Indian origin in Tanzania. Many of them are traders and they control a sizeable portion of the Tanzanian economy. They came to gradually control the trade in Zanzibar. Many of the buildings constructed then still remain in Stone Town, the focal trading point on the island.

South Africa

The Indian community in South Africa is more than a 150 years old and is concentrated in and around the city of Durban.[138] The vast majority of immigrant pioneer Gujaratis who came in the latter half of the 19th century were passenger Indians who paid for their own travel fare and means of transport to arrive and settle South Africa, in pursuit of fresh trade and career opportunities and as such were treated as British subjects, unlike the fate of a class of Indian indentured laborours who were transported to work on the sugarcane plantations of Natal Colony in dire conditions. Passenger Indians, who initially operated in Durban, expanded inland, to the South African Republic (Transvaal), establishing communities in settlements on the main road between Johannesburg and Durban. After wealthy Gujarati Muslim merchants began experiencing discrimination from repressive colonial legislation in Natal,[139] they sought the help of one young lawyer, Mahatma Gandhi to represent the case of a Memon businessman. Umar Hajee Ahmed Jhaveri was consequently elected the first president of the South African Indian Congress. Indians in South Africa could traditionally be bifurcated as either indentured labourers (largely from Tamil Nadu, with smaller amounts from UP and Bihar) and merchants (exclusively from Gujarat).

Peculiarities of the South African Gujarati diaspora include high amounts of Southern Gujaratis and a disproportionately high amount of Surti Sunni Vohra and Khatiawari Memons. Post democracy, sizeable amounts of new immigrants have settled in various parts of South Africa, including many newer Gujaratis.

Indians have played an important role in the anti-apartheid movement of South Africa.[140] Many were incarcerated alongside Nelson Mandela following the Rivonia Trial, and many became martyred fighting to end racial discrimination. Notable South African Indians of Gujarati heritage include Marxist freedom fighters such as Ahmed Timol (activist),[141] Yusuf Dadoo (activist),[142] Ahmed Kathrada (activist),[143] Amina Cachalia (activist) and Dullah Omar (activist),[144] as well as Ahmed Deedat (missionary), Imran Garda (Al Jazeera English) and Hashim Amla (cricketer).[145]

Oman

Oman, holding a strategically important position at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, has been the primary focus of trade and commerce for medieval Gujarati merchants for much of its history and Gujaratis, along with various other ethnic groups, founded and settled its capital port city, Muscat.[146] Some of the earliest Indian immigrants to settle in Oman were the Bhatias of Kutch, who have had a powerful presence in Oman dating back to the 16th century.[147] At the turn of the 19th century, Gujaratis wielded enough clout that Faisal bin Turki, the great-grandfather of the current ruler, spoke Gujarati and Swahili along with his native Arabic[148] and Oman's sultan Syed Said (1791-1856) was persuaded to shift his capital from Muscat to Zanzibar, more than two thousand miles from the Arabian mainland, on the recommendation of Shivji Topan and Bhimji families who lent money to the Sultan.[149] In modern times, business tycoon Kanaksi Khimji, from the famous Khimji family of Gujarat[150] was conferred title of Sheikh by the Sultan, the first ever use of the title for a member of the Hindu community.[151][152] The Muscati Mahajan is one of the oldest merchants associations founded more than a century ago.[153][154]

Southeast Asia

Gujaratis had a flourishing trade with Southeast Asia in the 15th and 16th centuries, and played a pivotal role in establishing Islam in the region.[155] Miller (2010) presented a theory that the indigenous scripts of Sumatra (Indonesia), Sulawesi (Indonesia) and the Philippines are descended from an early form of the Gujarati script. Tomé Pires reported a presence of a thousand Gujaratis in Malacca (Malaysia) prior to 1512.[156]Gujarati language continues to be spoken in Singapore and Malaysia.[3][157]

Malaysia

There estimated around 31,500 Gujarati in Malaysia. Most of this community work as traders and settled in the urban parts of Malaysia like Melaka, George Town, Kuala Lumpur and Ipoh.[157]

Cuisine

Gujarati food has famously been described as "the haute cuisine of vegetarianism" and meals have a subtle balance of sweet, tart and mild hot sensations on the palate.[158][159] Gujarati Jains, many Hindus and Buddhist in Gujarat are vegetarian. However, many Gujaratis such as Hindu Rajputs, Christians, and Muslims have traditionally eaten a variety of meats and seafood, although Muslims don't eat pork and Hindus don't eat beef.[160] Gujarati cuisine follows the traditional Indian full meal structure of rice, cooked vegetables, lentil dal or curry and roti. The different types of flatbreads that a Gujarati cooks are rotli or chapati, bhakhri, thepla or dhebara, puri (food), maal purah, and puran-pohli. Popular snacks such as Khaman, Dhokla, Pani Puri, Dhokli, dal-dhokli, Undhiyu, Jalebi, fafda, chevdoh, Samosa, papri chaat, Muthia, Bhajia, Patra, bhusu, locho, sev usal, fafda gathiya, vanela gathiya and Sev mamra are traditional Gujarati dishes savoured by many communities across the world.[161]

Khichdi – a mix of rice and mung dal, cooked with spice – is a popular and nutritious dish which has regional variations. Quite often the khichdi is accompanied by Kadhi. It is found satisfying by most Gujaratis, and cooked very regularly in most homes, typically on a busy day due to its ease of cooking. It can also become an elaborate meal such as a thali when served with several other side dishes such as a vegetable curry, yogurt, sabzi shaak, onions, mango pickle and papad.[162]

Spices have traditionally been made on grinding stones, however, since villages have seen rapid growth and industrialization in recent decades, today people may use a blender or grinder. People from north Gujarat use dry red chili powder, whereas people from south Gujarat prefer using green chili and coriander in their cooking. There is no standard recipe for Gujarati dishes, however the use of tomatoes and lemons is a consistent theme throughout Gujarat.[163] Traditionally Gujaratis eat mukhwas at the end of a meal to enhance digestion, and desserts such as aam shrikhand made using mango salad and hung curd are very popular.[163] In many parts of Gujarat, drinking chaas (chilled buttermilk) or soda after lunch or dinner is also quite common.

Surti delicasies include ghari which is a puri filled with khoa and nuts that is typically eaten during the festival Chandani Padva. Khambhat delicacies include famous sutarfeni – made from fine strands of sweet dough (rice or maida) garnished with pistachios, and halwasan which are hard squares made from broken wheat, khoa, nutmeg and pistachios.[164] A version of English custard is made in Gujarat that uses cornstarch instead of the traditional eggs. It is cooked with cardamom and saffron, and served with fruit and sliced almonds.[165] Gujarati families celebrate Sharad Purnima by having dinner with doodh-pauva under moonlight.[166][167]

Literature

The history of Gujarati literature may be traced to 1000 AD. Since then literature has flourished till date. Well known laureates of Gujarati literature are Jhaverchand Meghani, Avinash Vyas, Hemchandracharya, Narsinh Mehta, Gulabdas Broker, Akho, Premanand Bhatt, Shamal Bhatt, Dayaram, Dalpatram, Narmad, Govardhanram Tripathi, Mahatma Gandhi, K. M. Munshi, Umashankar Joshi, Suresh Joshi, Pannalal Patel, Imamuddin khanji Babi Saheb (Ruswa mazlumi), Niranjan Bhagat, Rajendra Keshavlal Shah, Raghuveer Chaudhari and Sitanshu Yashaschandra Mehta.

Kavi Kant, Kalapi and Abbas Abdulali Vasi are Gujarati language poets. Ardeshar Khabardar, Gujarati-speaking Parsi who was president of Gujarati Sahitya Parishad was a nationalist poet. His poem, Jya Jya Vase Ek Gujarati, Tya Tya Sadakal Gujarat (Wherever a Gujarati resides, there forever is Gujarat) depicts Gujarati ethnic pride and is widely popular in Gujarat.[168]

Gujarat Vidhya Sabha, Gujarat Sahitya Sabha, and Gujarati Sahitya Parishad are Ahmedabad based literary institutions promoting the spread of Gujarati literature. Saraswatichandra is a novel by Govardhanram Tripathi. Writers like Harindra Dave, Suresh Dalal, Jyotindra Dave, Dinkar Joshi, Prahlad Brahmbhatt, Tarak Mehta, Harkisan Mehta, Chandrakant Bakshi, Vinod Bhatt, Kanti Bhatt, Makarand Dave, and Varsha Adalja have influenced Gujarati thinkers.

Swaminarayan paramhanso, like Bramhanand, Premanand, contributed to Gujarati language literature with prose like Vachanamrut and poetry in the form of bhajans. Kanji Swami a spiritual mystic who was honored with the title, 'Koh-i-noor of Kathiawar' made literary contributions to Jain philosophy and promoted Ratnatraya.[169]

Gujarati theatre owes a lot to bhavai. Bhavai is a musical performance of stage plays. Ketan Mehta and Sanjay Leela Bhansali explored artistic use of bhavai in films such as Bhavni Bhavai, Oh Darling! Yeh Hai India and Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam. Dayro (gathering) involves singing and conversation reflecting on human nature.

Gujarati language is enriched by the Adhyatmik literature written by the Jain scholar, Shrimad Rajchandra and Pandit Himmatlal Jethalal Shah. This literature is both in the form of poetry and prose.[170]

Gujarati folklore

Folklores are important part of Gujarati culture. The folktales of Kankavati are religious in nature because they sprung from the ordinary day-to-day human cycle of life independent of, and sometimes deviating from the scriptures. They are part of the Hindu rituals and practices for marriage, baby shower, naming ceremony, the harvest and death, and are not merely religious acts but they reflect the lived life of people in rural and urban societies. The anthologies of Dadaji Ni Vato and Raang Chhe Barot are pragmatic with practical and the esoteric wisdom. Saurashtra Ni Rasdhar is a collection of love legends and depicts every shade of love and love is the main emotion which makes human world beautiful because it calls forth patience, responsibility, sense of commitment and dedication. Also the study of Meghani's works is quintessential because he was a trailblazer in exploring the vast unexplored heritage of Gujarati folklore. His folktales mirrors milieu of Gujarat, dialects, duhas, decors, humane values, sense of sacrifice and spirit of adventure, enthusiasm and, of course, the flaws in people. Meghani's folktales are verbal miniature of Gujarati culture.[171]

Notable people

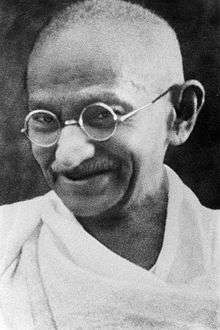

Mahatma Gandhi, the Father of India

Mahatma Gandhi, the Father of India.jpg) Sardar Patel, 1st Deputy Prime Minister of India and Indian statesman

Sardar Patel, 1st Deputy Prime Minister of India and Indian statesman Muhammed Ali Jinnah, the Father of Pakistan and the 1st Governor-General of Pakistan

Muhammed Ali Jinnah, the Father of Pakistan and the 1st Governor-General of Pakistan Jamshedji Nusserwanji Tata, Founder of the Tata group and known as one of the fathers of Indian industry

Jamshedji Nusserwanji Tata, Founder of the Tata group and known as one of the fathers of Indian industry Dr.Vikram Sarabhai, first Chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and head of India's Department of Atomic Energy, NASA

Dr.Vikram Sarabhai, first Chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and head of India's Department of Atomic Energy, NASA Sohrab Modi, actor, director, and producer

Sohrab Modi, actor, director, and producer Morarji Desai, the 4th Prime Minister of India

Morarji Desai, the 4th Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi, the 14th Prime Minister of India

Narendra Modi, the 14th Prime Minister of India

Business people

Notable Gujarati businesspeople include Dhirubhai Ambani, Mukesh Ambani, Anil Ambani, the Tata family, Gautam Adani, Karsanbhai Patel, Virji Vora, Currimbhoy Ebrahim, Hasmukhbhai Parekh, Nautamlal Bhagavanji Mehta, Nanji Kalidas Mehta, Muljibhai Madhvani, Mayur Madhvani, Meghji Pethraj Shah, Premchand Roychand, Walchand Hirachand, Ambalal Sarabhai, Sadruddin Hashwani, Fardunjee Marzban, Ashish Thakkar, Sudhir Ruparelia, Azim Premji, Rajdeepsinh Ribda, Uday Kotak, Dilip Shanghvi, Ramanbhai Patel, Adamjee Peerbhoy, J. D. C. Bytco, Hassam Moussa Rawat, Samir Mehta, Sudhir Mehta, Hina Shah, Ranchhodlal Chhotalal, Pankaj Patel, Bharat Desai, Adi Godrej

Politicians

Some of the most important figures involved in the independence movement were Gujarati. These include Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Patel, and father of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Gujaratis have also been prime ministers of India. They include Morarji Desai, and the current prime minister Narendra Modi. Others involved in Gujarat or Indian National politics include former chief minister Anandiben Patel, Shaktisinh Gohil, Nitin Patel, Saurabh Patel, Vitthal Radadiya, Vasanbhai Ahir, Purshottam Solanki, Shankersinh Vaghela, Poonamben Madam, Ahmed Patel, Vijay Rupani, Pradipsinh Jadeja, Arjun Modhwadia, Bharatsinh Solanki and Shankar Chaudhary.[173] There have been many Gujaratis involved in Pakistani politics, with the most prominent individuals being stateswoman and leading founder of Pakistan, Fatima Jinnah; the sixth Prime Minister of Pakistan, I.I. Chundrigar; and the current Deputy Chairman of the Senate of Pakistan, Saleem Mandviwalla. Other important Pakistani-Gujarati politicians include Mahmoud Haroon, Hussain Haroon, Muhammad Dilawar Khanji, Zubeida Rahimtoola, Ashraf W. Tabani, Arshad Vohra, Habib Rahimtoola, and Abdul Qadir Patel. UK politicians of Gujarati descent include Baron Desai, Baron Popat, Baron Verjee, Baron Dholakia, Baron Parekh, Shailesh Vara, and Priti Patel, among others as well as Canadian politician Arif Virani.

Social activists

Amit Jethwa, Vikram Sarabhai, Shrimad Rajchandra, Swami Dayanand Saraswati, Gopaldas Ambaidas Desai, Ashoka Mehta, Indulal Yagnik, Sanat Mehta, Ravi Shankar Vyas, Jhaverchand Meghani, Abbas Tyabji, Mahadev Desai, Jayanti Dalal, K.M. Munshi, Jugatram Dave, Odhavram, Shyamji Krishna Varma, Suhel Tirmizi and S. R. Rana.

Arts and entertainment

Famous Bollywood veterans of Gujarati heritage include Sohrab Modi,[174] Asha Parekh,[175] Sanjeev Kumar,[176] Jackie Shroff,[177] Aditya Pancholi, Dimple Kapadia,[178] Tina Ambani, Farooq Sheikh[179] and Mehtab.[180] Mehboob Khan was a pioneer of Hindi cinema, best known for directing the social epic drama Mother India (1957). As well as film directors such as Mehul Kumar, Mahesh Bhatt and Shreedatt Vyas[181] Anees Bazmee, Indian theatre personalities include Alyque Padamsee.[182] Award-winning producer Ismail Merchant, won six Academy Awards in collaboration with Merchant Ivory Productions,[183] whereas veteran playback singer Jaykar Bhojak has been performing in the industry for over two decades now.[184] Bollywood actresses Prachi Desai and Ameesha Patel have found fame in recent times.

Manmohan Desai is remembered for casting actors like Raj Kapoor, Babita and Amitabh Bachchan in hit films he directed such as Chhalia, Kismat, and Amar Akbar Anthony, and Babubhai Mistry pioneered the use of special effects in films.[185] Theatre veteran Chhel Vayeda was well known in Hindi cinema for being a popular production designer who designed the sets of over 50 films during his lifetime. Meanwhile, film tycoon Dalsukh Pancholi owned and operated one of the biggest cinema houses in Lahore and launched the careers of Punjabi film stars such as Noor Jehan in undivided India.[186]Wadia Movietone was a noted Indian film production company and studio based in Mumbai, established in 1933 by Wadia brothers J. B. H. Wadia and Homi Wadia, whom were originally Parsis from Surat.

Director Chaturbhuj Doshi is today known as was one of the founding fathers of Gujarati cinema. Gujarati films have made artists like Naresh Kanodia, Upendra Trivedi, Snehlata, Raajeev, Roma Maneck, and Aruna Irani popular in the entertainment industry. Among these dynamic actors, the late Upendra Trivedi who was a leading veteran of Gujarati cinema, made a popular pair with the heroine Snehlata and together they co-acted in more than 70 Gujarati films. Arvind Trivedi by whom the famous character of Ravana was played in Ramanad Sagar's popular TV serial Ramayana is his brother. In recent times, Gujarati drama film releases such as Little Zizou, Kevi Rite Jaish and Premji: Rise of a Warrior were positively received by audiences.[187][188][189]

Gujarati TV serials which showcase the traditional culture and lifestyle have made a prominent place in India. Comedy actors such as Paresh Rawal, Sarita Joshi, Urvashi Dholakia, Ketki Dave, Purbi Joshi, Disha Vakani, Dilip Joshi, Jamnadas Majethia, Deven Bhojani, Rashmi Desai, Satish Shah, Dina Pathak, Ratna Pathak Shah and Supriya Pathak have found a place in audience hearts and are presently the top actors on Indian television. Modern actors of Gujarati heritage who are more versatile include Darshan Pandya,[190] Vatsal Seth,[191] Avinash Sachdev, Esha Kansara,[192] Shrenu Parikh,[193] Amar Upadhyay, Viraf Patel, Ajaz Khan, Sameer Dattani,[194] Karishma Tanna,[195] Drashti Dhami,[196] Disha Savla,[197] Komal Thacker,[198] Vasim Bloch,[199] Parth Oza,[200] Tanvi Vyas, Nisha Rawal, Karan Suchak,[201] Jugal Jethi,[202] Isha Sharvani,[203] Pia Trivedi,[204] Sanjeeda Sheikh[205] Pooja Gor, Payal Rohatgi, Ravish Desai, Shefali Zariwala, and Shenaz Treasurywala.[206]

There are dedicated television channels airing Gujarati programs.

Well known musicians include the Vasant Rai, Charli XCX, pop star Alisha Chinai, Darshan Raval,[207] Shekhar Ravjiani,[208] Salim–Sulaiman, sons of Sadruddin Merchant who is veteran composer of the film industry, and ghazal singer Pankaj Udhas who is recipient of the Padma Shri. Famous sports icons of Gujarati heritage include Karsan Ghavri, Deepak Shodhan, Ashok Mankad,[209] Ghulam Guard, Prince Aslam Khan, Rajesh Chauhan, Parthiv Patel, Cheteshwar Pujara, Ajay Jadeja, Ravindra Jadeja, Chirag Jani, Munaf Patel, Axar Patel, Kiran More, Ian Dev Singh, and Sheldon Jackson.[210]

Science and technology

World renowned computer scientist and inventor of SixthSense, Pranav Mistry (Vice President of Research at Samsung), Sam Pitroda (Communication Revolution), and Indian physicist Vikram Sarabhai are Gujarati. Vikram Sarabhai is considered the "father of India's space programme", while Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha, a Parsi who is related to the Tata industrial family is the "father of India's nuclear science programme". Another well known Parsi pioneer Jamsetji Tata who founded Tata Group, India's biggest conglomerate company and devoted his life to four goals: setting up an iron and steel company, a world-class learning institution, a unique hotel and a hydro-electric plant, is the "father of Indian industry".[211]

Images

.jpg) Nagar Brahmins in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Nagar Brahmins in western India (c. 1855-1862).jpg) Bhatias in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Bhatias in western India (c. 1855-1862).jpg) Gujarati brokers in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Gujarati brokers in western India (c. 1855-1862).jpg) Gujarati accountants in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Gujarati accountants in western India (c. 1855-1862).jpg) Rajputs in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Rajputs in western India (c. 1855-1862).jpg) Parsis in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Parsis in western India (c. 1855-1862).jpg) Parsi priests in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Parsi priests in western India (c. 1855-1862).jpg) Lohanas in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Lohanas in western India (c. 1855-1862).jpg) Bohras in western India (c. 1855-1862)

Bohras in western India (c. 1855-1862)_(9938983803).jpg) Banians of Damnaggar (Kutch)

Banians of Damnaggar (Kutch).jpg) Khojas of Western India ca. 1855-1862

Khojas of Western India ca. 1855-1862.jpg) Memon men - photographs of Western India Series 1855-1862

Memon men - photographs of Western India Series 1855-1862

See also

- Jethwa Rajputs

- Rajputs of Gujarat

- Dharasana Satyagraha

- Navnirman Andolan

- Mahagujarat Movement

- Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule

- Genetic studies on Gujarati people

- Khatiawari Memons

References

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (9 May 2016). "Narendra Modi between Hindutva and subnationalism: The Gujarati asmita of a Hindu Hriday Samrat". India Review. Taylor & Francis Group. 15 (2): 196–217. doi:10.1080/14736489.2016.1165557.

- "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength - 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- Gujarati people at Ethnologue (20th ed., 2017)

- Rehman, Zia Ur (18 August 2015). "With a handful of subbers, two newspapers barely keeping Gujarati alive in Karachi". The News International. Karachi.

- Joel Millman (1998). The other Americans: how immigrants renew our country, our economy, and our values. Pennsylvania State University. p. 170. ISBN 9780140242171. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

There are over half a million Gujarati in America today.

- Dan Mayur (2017). Living Dreams. Mehta Publishing House. p. 335. ISBN 9789386342140. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

Nevertheless, the half or million so Gujaratis are entrepreneurial by nature...

- Michel, Patrick; Possamai, Adam; Turner, Bryan (20 April 2017). Religions, Nations, and Transnationalism in Multiple Modernities. Springer. p. 163. ISBN 9781137580115.

- "Gujaratis in Britain: Profile of a Dynamic Community". NATIONAL CONGRESS OF GUJARATI ORGANISATIONS (UK). Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Template:Cite Hinduism

- "NHS Profile, Canada, 2011, Census Data". Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Census shows Indian population and languages have exponentially grown in Australia". SBS Australia. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- Bharat Yagnik. "Oman was Gujaratis' first stop in their world sweep". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

Oman's capital Muscat was the first home for Gujarati traders away from the subcontinent. The Bhatia community from Kutch was the first among all Gujaratis to settle overseas — relocating to Muscat as early as 1507! The Bhatias' settlement in the Gulf is emphasized by Hindu places of worship, seen there since the 16th century. As historian Makrand Mehta asserts, "Business and culture go together."

- Rita d'Ávila Cachado. "Samosas And Saris:Informal Economies In The Informal City Among Portuguese Hindu families". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

The Hindus in Great Lisbon have similarities with Hindus in the United Kingdom: they are mostly from a Gujarati background and migrated from ex-colonial countries. Yet the colonial system they came from was mostly Portuguese, both in India and in East Africa... Nevertheless, a realistic estimate is that there are about 30,000 Hindus in Portugal. That includes Hindu-Gujaratis, who migrated in the early 1980s, as well as Hindu migrants from all parts of India and Bangladesh, who migrated in the late 1990s.

- Rupesh Patel. "The indian despora in New Zealand by todd nachowitz" (PDF). Retrieved 4 February 2015.

The Gujarati in New Zealand : they are mostly from a Gujarati background around 15.3 % in 2014. so there are about 26,622 Gujarati out of 176,000 Indian New Zealander in New Zealand. That includes mostly Hindu-Gujaratis, who migrated from Gujarat state

- M. K. Gandhi (2014). Hind Swaraj: Indian Home Rule. Sarva Seva Sangh Prakashan. ISBN 9789383982165. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- Minahan, James B. (2012). Ethnic groups of South Asia and the Pacific : an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 90. ISBN 978-1598846591. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

Anti-British sentiment led to a strong Gujarati participation in the Indian independence movement.

- Yagnik, Achyut; Sheth, Suchitra (2005). The shaping of modern Gujarat : plurality, Hindutva, and beyond. New Delhi: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0144000388. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- Gujarati communities across the globe : memory, identity and continuity. Mawani, Sharmina., Mukadam, Anjoom A. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books. 2012. ISBN 9781858565026. OCLC 779242654.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Singh, A. Didar; Rajan, S. Irudaya (6 November 2015). Politics of Migration: Indian Emigration in a Globalised World. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 9781317412243.

Gujarat has a very strong history of migration. The ancient Gujaratis were known for their trading with other countries. The Mercantile caste of western India, including Gujarat, has participated in overseas trade for many centuries and, as new opportunities arose in different parts of the British Empire, they were among the first to emigrate... The Gujarati Diaspora community is well known for their legendary entrepreneurship.

- Bhargava, ed. S.C. Bhatt, Gopal K. (2006). Daman & Diu. Delhi: Kalpaz publ. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-7835-389-0. Retrieved 4 February 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Blank, Jonah (15 March 2002). Mullahs on the Mainframe: Islam and Modernity Among the Daudi Bohras. The University of Chicago Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-226-05677-7.

Modern-day Mumbai is the capital of the state of Maharashtra, but until the creation of this state in 1960 the city has always been as closely linked to Gujarati culture as it has been to Marathi culture. During most of the colonial period, Gujaratis held the preponderance of economic and political power.

- Raymond Brady Williams (15 March 1984). A New Face of Hinduism: The Swaminarayan Religion. Cambridge University Press 1984. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-521-25454-0. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Rubber Boom Raises Hope Of Repatriates". Counter Currents. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Gujarat should learn from Kerala - The New Indian Express". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Edward A. Alpers (1975). Ivory and Slaves: Changing Pattern of International Trade in East Central Africa. University of California Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-520-02689-6. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

In the early 1660s, Surat merchants had 50 ships trading overseas, and the wealthiest of these, Virji Vora had an estate valued at perhaps 8 million rupees...

- Peck, Amelia (2013). Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-58839-496-5. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

Of the Asian trading communities the most successful were the Gujaratis, as witnessed not only by Pires and Barbosa but by a variety of other sources. All confirm that merchants from the Gujarati community routinely held the most senior post open to an expatriate trader, that of shah-bandar (controller of maritime trade).

- Farhat Hasan (2004). State and Locality in Mughal India: Power Relations in Western India, C.1572 - 1730. University Press, Cambridge. p. 42. ISBN 0-521-841 19-4. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

Mulla Abdul Ghafur, one of the richest merchants in Surat, his son, Mulla Abdul Hai, was awarded the title of 'umdat-tud-tujjar' (lit. the most eminent merchant) by the imperial court. Shantidas Shahu, a powerful merchant of Surat, was gifted an elephant and robe by the emperor, both things being emblems of imperial sovereignty, that 'symbolized the incorporation of the recipient into his [King's] person as his subordinate, to act in future as an extension of himself.

- Mawani, Sharmina; Mukadam, Anjoom A. (5 May 2016). Perspectives of female researchers : interdisciplinary approaches to the study of Gujarati identities. Mawani, Sharmina,, Mukadam, Anjoom A. Berlin. ISBN 9783832541248. OCLC 953734376.

- Mehta, Makrand (1991). Indian merchants and entrepreneurs in historical perspective : with special reference to shroffs of Gujarat, 17th to 19th centuries. Delhi: Academic Foundation. pp. 21, 27. ISBN 978-8171880171. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

The Gujarat region situated in the western part of India is known for its business activities since ancient times. The region has been agriculturally fertile and it also contains a long sea-coast enabling the merchants to undertake overseas trade. Thevenot held the Gujarati merchants in high esteem. Commending them for their skills in the currency business he states that he saw some 15000 banians in Ispahan, the capital of Persia operating exclusively as money-lenders and sharafs. He compared them with the Jews of Turkey and pointed out that they had their own residential settlements at Basra and Ormuz where they had constructed their temples.

- Kalpana Hiralal. Indian Family Businesses in Natal, 1870 – 1950 (PDF). Natal Society Foundation 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Poros, Maritsa V. (2010). Modern Migrations Gujarati Indian Networks in New York and London. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0804775830.

However, Gujaratis have been migrating as part of wide-ranging trade diasporas for centuries, long before capitalist development became concentrated in Europe and the United States.

- Vinay Lal. "Diaspora Purana: The Indic Presence in World Culture". Retrieved 22 October 2015.

Most historians, even those who have sought to move away from the narratives furnished by the framework of colonial knowledge, are unable to begin their narrative of the Indian diaspora before the nineteenth century, but the Gujaratis had justly established a diasporic presence in the early part of the second millennium. So renowned had the Gujaratis become for their entrepreneurial spirit, commercial networks, and business acumen that a bill of credit issued by a Gujarati merchant would be honored as far as 5,000 miles away merely on the strength of the community's business reputation. They traversed the vast spaces of the Indian Ocean world with confidence, and a Gujarati pilot guided Vasco da Gama's ship to India... Under Portuguese rule the Indian Ocean trading system went into precipitous decline, and not until the nineteenth century did the Gujarati diaspora find a new lease of life. Gujarati traders migrated under the British dispensation in large numbers to Kenya, Tanganyika, South Africa, and Fiji, among other places, and Mohandas Gandhi, himself a Gujarati, has recorded that the early political proceedings of the Indian community in South Africa were conducted in the Gujarati language. In East Africa their presence was so prominent that banknotes in Kenya, before the country acquired independence, had inscriptions in Gujarati. Khojas, or Gujarati Ismailis, flourished and even occupied positions as teachers and educators in Muslim countries around the world.

- Seeing Krishna in America The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and Its Movement to the West. McFarland Publishing. 2014. pp. 48, 49. ISBN 9780786459735. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

Among Gujaratis, emigration from India has a long history that has also affected Pushtimargiyas. As a seacoast mercantile population, the migration patterns of Gujaratis are ancient and may extend back over two millennia.

- Peggy Levitt. "Towards an Understanding of Transnational Community Forms and Their Impact on Immigrant Incorporation". research & seminars. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

In the Indian case, though organizational arrangements encourage U.S. and sending-country involvements, and the community displays high levels of economic and political integration, the goals of participation in home-country groups, the requirements of membership, and the insular social milieu in which participation occurs, reinforces homeland ties. Gujaratis may become the most transnational of groups because they assimilate selectively into the U.S. and maintain strong sending-country attachments

- Ghulam A. Nadri (2009). Eighteenth-Century Gujarat: The Dynamics of Its Political Economy, 1750-1800. p. 193. ISBN 978-9004172029.

- Eskild Petersen; Lin Hwei Chen; Patricia Schlagenhauf-Lawlor (14 February 2017). Infectious Diseases: A Geographic Guide. Wiley. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-119-08573-7.

- André Wink (1997) Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slavic Kings and the Islamic conquest, BRILL ISBN 90-04-10236-1 pp.355–356

- "Gujarat & India Same, Different But Same". outlookindia.com.

A historically mercantile culture, widespread influence of Jainism, diluted casteism and an intrinsic irreverence makes society and polity in Gujarat different from other Indian states. Centre-right in their economic leaning, people here naturally gravitate towards leaner governments with high standards of governance... Absence of local rulers’ courts meant that trade-mercantile guilds ran affairs and administration. The kind of socio-cultural influence that pervaded the feudal kingdoms of Rajasthan etc was absent in Gujarat. The trade guilds were akin to the influential mercantile guilds of Belgium and the Netherlands, which contributed to making the Dutch world leaders in finance. In Gujarat, this cascaded into a strong entrepreneurial culture. As the English philosopher Bertrand Russell puts it, governments which consist of mercantilists tend to be more prudent in running the administration.

- Jacobsen, Knut A. (11 August 2015). Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India. Routledge. ISBN 9781317403586.

- Pearson, Michael Naylor (1 January 1976). Merchants and Rulers in Gujarat: The Response to the Portuguese in the Sixteenth Century. University of California Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780520028098.

Mahajan means different things in different parts of India; it can refer to an individual banker, a money-lender, a merchant, or an unspecified "great man". In Gujarat it usually meant a body representing a group of people engaged in the same commercial occupation, a governing council with an elected or occasionally hereditary headman...

- "Going global". The Economist. 19 December 2015.

Whereas one religion, Protestantism, has often been associated with the rise of Anglo-Saxon capitalism, Gujarati capitalism was much more a fusion of influences. Ethnic and religious diversity became a source of strength, multiplying the trading networks that each community could exploit. Pragmatism and flexibility over identity, and a willingness to accommodate, perhaps inherited from the mahajans, are strong Gujarati traits, argues Edward Simpson of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. Gujaratis have been adept at remaining proudly Gujarati while becoming patriotically British, Ugandan or Fijian—an asset in a globalised economy.

- Sundar, Pushpa (24 January 2013). Business and Community: The Story of Corporate Social Responsibility in India. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9788132111535.

The merchants were organized into mahajans or guilds with hereditary seths. A mahajan could include merchants of different religions and there was no strict segregation of religious, social, and occupational functions.

- Rai, Rajesh; Reeves, Peter; Pro, Visiting Professor Coordinator South Asia Studies Programme Peter Reeves (25 July 2008). The South Asian Diaspora: Transnational Networks and Changing Identities. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 9781134105953.

For Banias and Muslims there was a clear division of commercial activities based on religious persuasions and canonical injunctions. For example, Muslim merchants did not deal in printed textiles with motifs of living creatures on it, while these were procured by the Bania and Jain brokers. On the other hand Bania and Jain merchants would not deal in the trade of animals while Muslims did not have any problems with such trade. Similarly, Muslim merchants dominated the shipping trade and many were big ship-owners. The nakhudas and the lascars were also primarily from the Muslim community. On the other hand, some of the Banias and the Jains were prominent merchants and they organized an extensive trade from Gujarat to other parts of Asia. Thus, two forms of trade which formed the shipping and commerce were controlled by these two major communities of Gujarati merchants. For both these communities their relationship necessitated mutual understanding and interdependence in commercial matters so that they could play a complementary role in advancing their trading interests

- Malik, Ashish; Pereira, Vijay (20 April 2016). Indian Culture and Work Organisations in Transition. Routledge. ISBN 9781317232025.

He found that Gujaratis are highly family-oriented valuing family network and highly familial. They are also spiritualistic, religious and relationship oriented, attaching importance to co-operation. They are accepted to be materialistic. Panda, on the basis of empirical evidence, has named the society as 'collectivist familial (clannish) society'. Further, Gujarati society is found to have a high social capital. The dominant cultural characteristics identified from this study, which are essentially 'familial', 'co-operative' and 'non-hierarchical' (democratic) are consistent with Joshi's findings.

- Berger, Peter; Heidemann, Frank (3 June 2013). The Modern Anthropology of India: Ethnography, Themes and Theory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134061112.

Gujaratis continuously redefine and contest caste and hiearchical values in a competitive pluralistic social environment. In post-colonial Gujarat, the merchant culture and its values of purity and economic wealth have prevailed over plural notions of hierarchy (Tambs-Lyche 1982)

- "Gujarat Religion Census 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.

- Anjali H. Desai (2007). India Guide Gujarat. India Guide Publications. ISBN 9780978951702.

- Mawani, Sharmina; Mukadam, Anjoom A. (2014). Globalisation, diaspora and belonging : exploring transnationalism and Gujarati identity. Mawani, Sharmina,, Mukadam, Anjoom A. Jaipur. ISBN 9788131606322. OCLC 871342185.

- Gujarat. Popular Prakashan. 2003. ISBN 9788179911068.

- Pedro Machado (2014). Ocean of Trade: South Asian merchants, Africa and the Indian Ocean, c.1750 - 1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-107-07026-4. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

Hindu Vaniya networks from Kathiawar, in particular, operated prominently in the region, and directed their trade primarily to Yemen, and Hadramawt. They were also active in the early eighteenth century in the southern Red Sea, where Mocha and other ports such as Aden provided them with their principal markets

- Cordell Crownover (5 October 2014). Ultimate Handbook Guide to Muscat : (Oman) Travel Guide. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

As an important port-town in the Gulf of Oman, Muscat attracted foreign tradesman and settlers, such as the Persians, the Balochs and Gujaratis.

- Andrew Gardner (1969). City of Strangers: Gulf Migration and the Indian Community in Bahrain. Cornell University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8014-7602-0. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

Other Indian groups with a long-standing presence in Bahrain include the Gujarati businessmen whose enterprises historically centered on the trade of gold; the Bohra community, an Indian Muslim sect with a belief system particularly configured around business...

- Ababu Minda Yimene (2004). An African Indian Community in Hyderabad: Siddi Identity, Its Maintenance and Change. pp. 66, 67. ISBN 978-3-86537-206-2. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

Some centuries later, the Gujarati merchants established permanent trading posts in Zanzibar, consolidating their influence in the Indian Ocean... Gujarati Muslims, and their Omani partners, engaged in a network of mercantile activities among Oman, Zanzibar and Bombay. Thanks to those mercantile Gujarati, India remained by far the principal trading partner of Zanzibar.

- Irfan Habib (2011). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500. p. 166. ISBN 978-81-317-2791-1. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

In the Persian Gulf, Hurmuz (Hormuz), was the most important entrepot for the international exchange for goods which were either bartered or purchased with money. The rise of Hurmuz in the thirteenth century followed the decline of the neighbouring entrepot of Qays, where there was a community of Gujarati Bohra merchants

- Paul R. Magocsi (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. University of Toronto Press. p. 631. ISBN 978-0-8020-2938-6. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

Gujarat's proximity to the Arabian Sea has been responsible for the ceaseless mercantile and maritime activities of its people. Through the ports of Gujarat, some of which date back to the dawn of history, trade and commerce flourished, and colonizers left for distant lands.

- Gujaratis in the West : evolving identities in contemporary society. Mukadam, Anjoom A., Mawani, Sharmina. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Pub. 2007. ISBN 9781847183682. OCLC 233491089.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Chidanand Rajghatta. "Global Gujaratis: Now in 129 nations". The economic times. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

A lot of the spread worldwide took place after a pit-stop in East Africa, right across the sea from Gujarat. When Idi Amin turfed out some 100,000 Indians (mostly Gujaratis) from Uganda in 1972, most of them descended on Britain before peeling off elsewhere.

- Premal Balan & Kalpesh Damor. "Thanks to NRIs, 3 small Gujarat villages each have Rs 2,000cr bank deposits". the times of india. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

No wonder bank hoardings flashing interest rates for NRI deposits (up to 10%) is a common sight in these villages. "Some villages in Kutch like Madhapar and Baladia have very high NRI deposits. To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest in the country," said K C Chippa, former convener of the State Level Banker's Committee (SLBC) Gujarat. Between them, Madhapar, Baladia and Kera have 30 bank branches and 24 ATMs.

- Piyush Mishra. "NRI deposits in Gujarat cross Rs 50K crore mark". the times of India. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

Gujaratis form 33% of the Indian diaspora and Gujarat is among the top five states in the country in terms of NRI deposits. RBI data shows there was a little over $115 billion (about Rs 7 lakh crore) in NRI accounts in India in 2014-15, with Gujarat accounting for 7.78% of the kitty.

- Fernandez-Kelly, Patricia; Portes, Alejandro, eds. (1 July 2015). The State and the Grassroots: Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents. Berghahn Books. p. 99. ISBN 9781782387350. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- Kachru, Braj B.; Kachru, Yamuna; Sridhar, S. N. (2008). Language in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 531. ISBN 9781139465502.

- The Gujaratis of Pakistan

- "JAVED MIANDAD: profile". karismatickarachi. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Chapter 9 - Charity Galore in Journal of Informal Religious Meetings, vol. 5(8), Oct/Nov 2004".

- Khaled Ahmed (23 February 2012). "Gujarat's gifts to India and Pakistan". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- "The Gujaratis of Pakistan – By Aakar Patel". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Keely, Charles B. (May 1971). "Effects of the immigration act of 1965 on selected population characteristics of immigrants to the United States". Demography. 8 (2): 157–169. doi:10.2307/2060606. JSTOR 2060606. PMID 5163987.

- Khandelwal, MS (1995). The politics of space in South asian Diaspora, Chapter 7 Indian immigrants in Queens, New York City: patterns of spatial concentration and distribution, 1965–1990 - Nation and migration: - books.google.com. Philadelphia, USA: University of Pennsylvania. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8122-3259-2. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Colin Clarke; Ceri Peach; Steven Vertovec (26 October 1990). South Asians Overseas: Migration and Ethnicity. Cambridge University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-521-37543-6.

- Rangaswamy, Padma (2007). Indian Americans (2007 Hardcover ed.). New York: Chelsea House. p. 55. ISBN 9780791087862.

gujarati.

- edited by Greve, Joel A.C.; Baum, Henrich R.; Authored by Kalnins, Arthur; Chung, Wilbur (2001). Multiunit organization and multimarket strategy (1. ed.). New York: JAI. pp. 33–48. ISBN 978-0-7623-0721-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Virani, Aarti. "Why Indian Americans Dominate the U.S. Motel Industry". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- HIRAL DHOLAKIA-DAVE (18 October 2006). "42% of US hotel business is Gujarati". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

Gujaratis, mainly Patels, now own 21,000 of the 53,000 hotels and motels in the US. It makes for a staggering 42% of the US hospitality market, with a combined worth of $40 billion.

- Rangaswami, Padma (2000). Namaste America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis. University park, PA, USA: Pennsylvania State University press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0271--01980-2.

- Ashish Chauhan (15 August 2016). "Air India launches Ahmedabad to Newark flight". The Times of India. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Drew Joseph (14 August 2010). "Bera Hopes to Wipe Out Lungren Despite GOP Wave". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- "Gujarati Woman Aims for House", The Times of India, 1 January 2010.

- "Gujarati NRI Sonal Shah appointed Obama's adviser". DeshGujarat. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

NRI Gujarati Sonal Shah, an eminent economist who heads Google's philanthropic arm, has been appointed an advisory board member by US President-elect Barack Obama to assist his team in smooth transition of power.

- Nuzzi, Olivia (5 February 2018). "White House Official Called Trump 'a Deplorable'". New York.

- "2 Gujarati-origin among America's super-rich". dna india. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Raheel Dhattiwala. "The million dollar man from Gujarat". The Economic Times. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

AT was lucky to meet the Ahmedabad-born, 50-year-old business honcho in person.

- "FIVE INDIAN AMERICANS AMONG FORBES 400 RICHEST". global gujarat news. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

Next comes Romesh T. Wadhwani (No. 250), Founder and Chairman, Symphony Technology Group, with a net worth of $1.9 billion. Landing in the US with only a few dollars in his pocket, he developed business software firm Aspect Development. Today his portfolio includes more than 10 different enterprise software companies.

- "Top 10 Richest Gujarati in the India". global gujarat news. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

Romesh Wadhwani is the chairman and CEO of Symphony Technology Group, which brings in $2.5 billion in annual revenues. In January 2017 the firm sold MSC Software to Swedish company Hexagon for $834 million. After graduating from the Indian Institute of Technology, he went to Carnegie Mellon and received a Ph.D. in 1972 in electrical engineering.

- "IG Online Interview: Raj Bhavsar (USA)". intlgymnast. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

Born in Houston, Bhavsar is 100 percent Gujarati; his father hails from Vadadora (Baroda), a city in the small Indian state of Gujarat, near Mumbai. His mother was born in Kampala, Uganda, but was educated in Gujurat. Most of Bhavsar's relatives are Gujarati.

- "Savan Kotecha, Songwriter". ofindianorigin.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

I come from a pretty traditional Gujarati family and that made getting into the music business pretty tricky. My parents like most Indian parents, wanted me to go to Uni and be a Doctor or Lawyer. That meant I was on my own for the most part as far as figuring out how to 'make it'. It also gave me something to prove which made me work extra hard.

- "Movers and shakers". india today. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

"We are close to our extended families in Ahmedabad and Mumbai and grew up with Gujarati culture as a predominant influence in our lives.... The Gujarati community has done it all in the US — from doctors to entrepreneurs, from retail to the hospitality industry.

- "Stereotypes are very hard to escape: Noureen DeWulf". Zee News India. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

DeWulf, a Gujarati Muslim by origin, has carved out a successful career for herself in Hollywood and her repertoire includes Hollywood films like `West Bank Story` and `Ghosts of Girlfriends Past` besides TV shows `Maneater`, `90210` and `Girlfriends`.

- Derek Laud (2015). The Problem With Immigrants. Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1849548779. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Shastri Ramachandaran. "India has much to learn from Britain and Germany". dnaindia.com. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

Britain places high value on the power of commerce. After all, its political and military dominance when Britannia ruled the waves was founded on its trading power. The Gujaratis know this better than many others, which explains their prosperity and success in the UK.

- "Asian corner shops are in decline". Daily Mail. London.

- Chitra Unnithan (23 May 2012). "Family is key to success of Gujarati businessmen in Britain". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

British Gujaratis were also more successful than other minority communities in Britain because they had already tasted success in Africa. The book also says that Gujarati Hindus have become notably successful public citizens of contemporary, capitalistic Britain; on the other hand, they maintain close family links with India. "British Gujaratis have been successful in a great variety of fields. Many younger Gujaratis took to professions rather than stay behind the counter of their parents' corner shops, or they entered public life, while those who went into business have not remained in some narrow commercial niche," says the book.

- Sudeshna Sen (8 January 2013). "How Gujaratis changed corner shop biz in UK". The Economic Times. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

"What most people don't get is that those who took the Arab dhows in the 17th and 18th century to leave their villages and set up life in an alien land were already an entrepreneurial and driven minority, in search of a better life. They communicated that hunger to their children," says Raxa Mehta, director at Nomura, based in Tokyo and first generation child of Kenyan Indian parents. So it doesn't surprise the Gujaratis that they did well in Britain – it only surprises the Brits and Indians. The Gujaratis are a trader community. As Manubhai says, they always left the fighting to the others. If there's one diaspora community that East African Asians model themselves on, it's the Jews. Except of course, the Jews get more publicity than they do.

- Rodger, R; Herbert, J (2008). "'Narratives of South Asian women in Leicester 1964 - 2004', no. 2, pp." (PDF). Oral History. 36 (2): 554–563.

- "London's Gujarati Christians celebrate milestone birthday". www.eauk.org.

- Malik, edited by K.N.; Robb, Peter (1994). India and Britain : recent past and present challenges. New Delhi: Allied Publishers. ISBN 9788170233503. Retrieved 5 February 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Jain Samaj Europe". Archived from the original on 23 January 2015.

- "Shree Kutch Leva Patel Community (UK)". sklpc.com/.

- Eliezer Ben Rafael, Yitzhak Sternberg (2009). Transnationalism: Diasporas and the Advent of a New (Dis)order. p. 531. ISBN 978-90-04-17470-2. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Shree Maher Samaj UK". maheronline.org/. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Gujarati Arya Kshatriya Mahasabha-UK". gakm.co.uk/?p=about. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Gujarati Muslim Marriage, a dedicated service to assist Gujarati Muslims to marry within the community.

- Backman, M; Butler C, C (2003). BIG in Asia - Understanding Asia's Overseas Indians. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781403914484_4. ISBN 978-0-230-00027-8.

- Lum, Kathryn (16 October 2014). "The rise and rise of Belgium's Indian diamond dynasties". The Conversation.

- "NHS Profile, Canada, 2011, Census Data". Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Toronto Garba: North America's Largest Raas-Garba". www.torontogarba.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Al Noor Kassum (2007). Africa's winds of change : memoirs of an international Tanzanian. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-583-8. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Versi, Salima. "Make This Your Home: The Impact of Religion on Acculturation: The Case of Canadian Khoja Nizari Isma'ilis from East Africa". Queens University. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- Ajit Jain. "'Gujarati diaspora integral to state's success'". theindiandiaspora.com. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

According to him "It was a very warm discussion. PM Modi knows Canada well because we have been such active participants in Vibrant Gujarat for over 18 years now. He also knows very well how strong the Gujarati diaspora is in Canada. It may be up to one quarter of all the Indo-Canadians in this country, and so their success has been part of Gujarat's success." And "the prime minister (of India) recognizes that," Alexander stated emphatically.

- "Executive Profiles - Group Heads | TD Bank Group". www.td.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Zain Verjee – Atlanta, Georgia". alusainc.wordpress.com. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

Verjee also has produced successful radio campaigns spreading awareness of HIV/AIDS, road safety and violence against women. Her community efforts include work with Street Children and with Operation Smile. Verjee received her undergraduate degree in English from McGill University in Montreal and studied at York University in Canada. She speaks Gujarati, Kiswahili and conversational French.

- "The Velshi Exchange". alivelshi.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Avan Jogia

- "Arif Virani wins in Parkdale-High Park | The Star". thestar.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Canada's Prime Minister Stephen Harper is not a real Evangelical Christian". the nonconformer.wordpress.com. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

Jaffer, who is an Ismaili Muslim of Gujarati origin, became Canada’s youngest non-white MP at the age of 25 in 1997. He served four terms till his loss in the 2008 parliamentary elections.

- "The Genius of Naheed Nenshi". The Parallel Parliament. 19 February 2014.

But there was more. In two words, he was challenging and electric. And his own background is so varied as to make him unique. He’s an east Indian who lived in Tanzania prior to coming to Canada. He’s slightly over 40 years of age, a Muslim, has a degree from Harvard, and just happened to best three solid status quo challengers to win Calgary’s top job. Seated together at the front of that assembly room, I realized it was the very mystique about him that caused people to look at things in a new fashion.

- "Omar Sachedina". ctvnews.ca. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

Sachedina speaks French, Gujarati, and Kutchi. He enjoys travelling, music, and sampling food from around the world

- "Our Team: Prashant Pathak - ReichmannHauer Capital Partners". www.rhcapitalpartners.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- JSTOR.<Expulsion of a minority: essays on Ugandan Asians.>

- Gregory, Robert G. (1993), Quest for equality: Asian politics in East Africa, 1900-1967, New Delhi: Orient Longman Limited, p. 26, ISBN 978-0-863-11-208-9