Group 3 element

Group 3 is a group of elements in the periodic table. This group, like other d-block groups, should contain four elements, but it is not agreed what elements belong in the group. Scandium (Sc) and yttrium (Y) are always included, but the other two spaces are usually occupied by lanthanum (La) and actinium (Ac), or by lutetium (Lu) and lawrencium (Lr); less frequently, it is considered the group should be expanded to 32 elements (with all the lanthanides and actinides included) or contracted to contain only scandium and yttrium. When the group is understood to contain all of the lanthanides, it subsumes the rare-earth metals. Yttrium, and less frequently scandium, are sometimes also counted as rare-earth metals.

| Group 3 in the periodic table | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| ↓ Period | |||||||||

| 4 |  21 Transition metal | ||||||||

| 5 |  39 Transition metal | ||||||||

| 6 |  57 Lanthanide | ||||||||

| 7 | Actinium (Ac*) 89 Actinide | ||||||||

|

* Whether the elements lutetium (Lu) and lawrencium (Lr), in period 6 and 7, are in group 3 is disputed. The grouping used in this article places La and Ac in group 3, which is the most common form. For other groupings, see group 3 borders. | |||||||||

|

Legend

| |||||||||

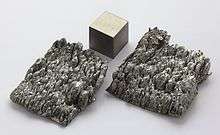

Three group 3 elements occur naturally: scandium, yttrium, and either lanthanum or lutetium. Lanthanum continues the trend started by two lighter members in general chemical behavior, while lutetium behaves more similarly to yttrium. While the choice of lutetium would be in accordance with the trend for period 6 transition metals to behave more similarly to their upper periodic table neighbors, the choice of lanthanum is in accordance with the trends in the s-block, which the group 3 elements are chemically somewhat similar to (as are the lanthanides and actinides in general, as well as the heavy elements of groups 4 and 5). They all are silvery-white metals under standard conditions. The fourth element, either actinium or lawrencium, has only radioactive isotopes. Actinium, which occurs only in trace amounts, continues the trend in chemical behavior for metals that form tripositive ions with a noble gas configuration; synthetic lawrencium is calculated and partially shown to be more similar to lutetium and yttrium. So far, no experiments have been conducted to synthesize any element that could be the next group 3 element. Unbiunium (Ubu), which could be considered a group 3 element if preceded by lanthanum and actinium, might be synthesized in the near future, it being only three spaces away from the current heaviest element known, oganesson.

History

In 1787, Swedish part-time chemist Carl Axel Arrhenius found a heavy black rock near the Swedish village of Ytterby, Sweden (part of the Stockholm Archipelago).[1] Thinking that it was an unknown mineral containing the newly discovered element tungsten,[2] he named it ytterbite.[note 1] Finnish scientist Johan Gadolin identified a new oxide or "earth" in Arrhenius' sample in 1789, and published his completed analysis in 1794;[3] in 1797, the new oxide was named yttria.[4] In the decades after French scientist Antoine Lavoisier developed the first modern definition of chemical elements, it was believed that earths could be reduced to their elements, meaning that the discovery of a new earth was equivalent to the discovery of the element within, which in this case would have been yttrium.[note 2] Until the early 1920s, the chemical symbol "Yt" was used for the element, after which "Y" came into common use.[5] Yttrium metal was first isolated in 1828 when Friedrich Wöhler heated anhydrous yttrium(III) chloride with potassium to form metallic yttrium and potassium chloride.[6][7]

In 1869, Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev published his periodic table, which had empty spaces for elements directly above and under yttrium.[8] Mendeleev made several predictions on the upper neighbor of yttrium, which he called eka-boron. Swedish chemist Lars Fredrik Nilson and his team discovered the missing element in the minerals euxenite and gadolinite and prepared 2 grams of scandium(III) oxide of high purity.[9][10] He named it scandium, from the Latin Scandia meaning "Scandinavia". Chemical experiments on the element proved that Mendeleev's suggestions were correct; along with discovery and characterization of gallium and germanium this proved the correctness of the whole periodic table and periodic law. Nilson was apparently unaware of Mendeleev's prediction, but Per Teodor Cleve recognized the correspondence and notified Mendeleev.[11] Metallic scandium was produced for the first time in 1937 by electrolysis of a eutectic mixture, at 700–800 °C, of potassium, lithium, and scandium chlorides.[12]

In 1751, the Swedish mineralogist Axel Fredrik Cronstedt discovered a heavy mineral from the mine at Bastnäs, later named cerite. Thirty years later, the fifteen-year-old Vilhelm Hisinger, from the family owning the mine, sent a sample of it to Carl Scheele, who did not find any new elements within. In 1803, after Hisinger had become an ironmaster, he returned to the mineral with Jöns Jacob Berzelius and isolated a new oxide which they named ceria after the dwarf planet Ceres, which had been discovered two years earlier.[13] Ceria was simultaneously independently isolated in Germany by Martin Heinrich Klaproth.[14] Between 1839 and 1843, ceria was shown to be a mixture of oxides by the Swedish surgeon and chemist Carl Gustaf Mosander, who lived in the same house as Berzelius: he separated out two other oxides which he named lanthana and didymia.[15] He partially decomposed a sample of cerium nitrate by roasting it in air and then treating the resulting oxide with dilute nitric acid.[16] Since lanthanum's properties differed only slightly from those of cerium, and occurred along with it in its salts, he named it from the Ancient Greek λανθάνειν [lanthanein] (lit. to lie hidden).[14] Relatively pure lanthanum metal was first isolated in 1923.[17]

Lutetium was independently discovered in 1907 by French scientist Georges Urbain,[18] Austrian mineralogist Baron Carl Auer von Welsbach, and American chemist Charles James[19] as an impurity in the mineral ytterbia, which was thought by most chemists to consist entirely of ytterbium. Welsbach proposed the names cassiopeium for element 71 (after the constellation Cassiopeia) and aldebaranium (after the star Aldebaran) for the new name of ytterbium but these naming proposals were rejected, although many German scientists in the 1950s called the element 71 cassiopeium. Urbain chose the names neoytterbium (Latin for "new ytterbium") for ytterbium and lutecium (from Latin Lutetia, for Paris) for the new element. The dispute on the priority of the discovery is documented in two articles in which Urbain and von Welsbach accuse each other of publishing results influenced by the published research of the other.[20][21] The Commission on Atomic Mass, which was responsible for the attribution of the names for the new elements, settled the dispute in 1909 by granting priority to Urbain and adopting his names as official ones. An obvious problem with this decision was that Urbain was one of the four members of the commission.[22] The separation of lutetium from ytterbium was first described by Urbain and the naming honor therefore went to him, but neoytterbium was eventually reverted to ytterbium and in 1949, the spelling of element 71 was changed to lutetium.[23][24] Ironically, Charles James, who had modestly stayed out of the argument as to priority, worked on a much larger scale than the others, and undoubtedly possessed the largest supply of lutetium at the time.[25]

André-Louis Debierne, a French chemist, announced the discovery of actinium in 1899. He separated it from pitchblende residues left by Marie and Pierre Curie after they had extracted radium. In 1899, Debierne described the substance as similar to titanium[26] and (in 1900) as similar to thorium.[27] Friedrich Oskar Giesel independently discovered actinium in 1902[28] as a substance being similar to lanthanum and called it "emanium" in 1904.[29] After a comparison of the substances half-lives determined by Debierne,[30] Hariett Brooks in 1904, and Otto Hahn and Otto Sackur in 1905, Debierne's chosen name for the new element was retained because it had seniority, despite the contradicting chemical properties he claimed for the element at different times.[31][32]

Lawrencium was first synthesized by Albert Ghiorso and his team on February 14, 1961, at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (now called the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) at the University of California in Berkeley, California, United States. The first atoms of lawrencium were produced by bombarding a three-milligram target consisting of three isotopes of the element californium with boron-10 and boron-11 nuclei from the Heavy Ion Linear Accelerator (HILAC).[33] The nuclide 257103 was originally reported, but then this was reassigned to 258103. The team at the University of California suggested the name lawrencium (after Ernest O. Lawrence, the inventor of cyclotron particle accelerator) and the symbol "Lw",[33] for the new element, but "Lw" was not adopted, and "Lr" was officially accepted instead. Nuclear-physics researchers in Dubna, Soviet Union (now Russia), reported in 1967 that they were not able to confirm American scientists' data on 257103.[34] Two years earlier, the Dubna team reported 256103.[35] In 1992, the IUPAC Trans-fermium Working Group officially recognized element 103, confirmed its naming as lawrencium, with symbol "Lr", and named the nuclear physics teams at Dubna and Berkeley as the co-discoverers of lawrencium.[36]

If lutetium and lawrencium are considered to be group 3 elements, then extrapolation from the Aufbau principle would predict that the next element in the group should be element 153, unpenttrium (Upt). According to the principle, unpenttrium should have an electronic configuration of [Og]8s25g186f147d1[note 3] and filling the 5g-subshell should be stopped at element 138. However, elements beyond 120 are predicted to stop following the Aufbau principle: the 7d-orbitals are calculated to start being filled on element 137, while the 5g-subshell closes only at element 144, after filling of 7d-subshell begins. Therefore, it is hard to calculate which element should be the next group 3 element.[37] Calculations suggest that unpentpentium (Upp, element 155) could also be the next group 3 element,[38] as could unpentseptium (Ups, element 157).[39] If lanthanum and actinium are considered group 3 elements, then element 121, unbiunium (Ubu), should be the fifth group 3 element. The element is calculated to have electronic configuration of [Og]8s28p1/21, with an anomalous p-electron similar to that of lawrencium.[37] The synthesis of unbiunium was attempted unsuccessfully in 1977,[40] though its proximity to known elements and advances in accelerator technology may enable its creation in the near future.[41][42] No other synthesis experiments have been conducted.

Characteristics

Chemical

| Z | Element | Electron configuration |

|---|---|---|

| 21 | scandium | 2, 8, 9, 2 |

| 39 | yttrium | 2, 8, 18, 9, 2 |

| 57 | lanthanum | 2, 8, 18, 18, 9, 2 |

| 89 | actinium | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 9, 2 |

Like other groups, the members of this family show patterns in their electron configurations, especially the outermost shells, resulting in trends in chemical behavior. However, lawrencium is an exception, since its last electron is transferred to the 7p1/2 subshell due to relativistic effects.[43][44]

Most of the chemistry has been observed only for the first three members of the group; chemical properties of both actinium and especially lawrencium are not well-characterized. The remaining elements of the group (scandium, yttrium, lutetium) are reactive metals with high melting points (1541 °C, 1526 °C, 1652 °C respectively). They are usually oxidized to the +3 oxidation state, even though scandium,[45] yttrium[46][47] and lanthanum[17] can form lower oxidation states. The reactivity of the elements, especially yttrium, is not always obvious due to the formation of a stable oxide layer, which prevents further reactions. Scandium(III) oxide, yttrium(III) oxide, lanthanum(III) oxide and lutetium(III) oxide are white high-temperature-melting solids. Yttrium(III) oxide and lutetium(III) oxide exhibit weak basic character, but scandium(III) oxide is amphoteric.[48] Lanthanum(III) oxide is strongly basic.

Physical

Elements that show tripositive ions with electronic configuration of a noble gas (scandium, yttrium, lanthanum, actinium) show a clear trend in their physical properties, such as hardness. At the same time, if group 3 is continued with lutetium and lawrencium, several trends are broken. For example, scandium and yttrium are both soft metals. Lanthanum is soft as well; all these elements have their outermost electrons quite far from the nucleus compared to the nuclei charges. Due to the lanthanide contraction, lutetium, the last in the lanthanide series, has a significantly smaller atomic radius and a higher nucleus charge,[49] thus making the extraction of the electrons from the atom to form metallic bonding more difficult, and thus making the metal harder. However, lutetium suits the previous elements better in several other properties, such as melting[50] and boiling points.[51] Very little is known about lawrencium, and none of its physical properties have been confirmed.[52][53]

| Name | Scandium | Yttrium | Lanthanum | Actinium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting point[50] | 1814 K, 1541 °C | 1799 K, 1526 °C | 1193 K, 920 °C | 1323 K, 1050 °C |

| Boiling point[51] | 3109 K, 2836 °C | 3609 K, 3336 °C | 3737 K, 3464 °C | 3471 K, 3198 °C |

| Density | 2.99 g·cm−3[54] | 4.47 g·cm−3[55] | 6.162 g·cm−3 | 10 g·cm−3 |

| Appearance | silver metallic | silver white | gray | silvery |

| Atomic radius[49] | 162 pm | 180 pm | 187 pm | 215 pm |

Composition of group 3

It is disputed whether lanthanum and actinium should be included in group 3, rather than lutetium and lawrencium. Other d-block groups are composed of four transition metals,[note 6] and group 3 is sometimes considered to follow suit. Scandium and yttrium are always classified as group 3 elements, but it is controversial which elements should follow them in group 3, lanthanum and actinium or lutetium and lawrencium. Scerri has proposed a resolution to this debate on the basis of moving to a 32-column table and consideration of which option results in a continuous sequence of atomic number increase. He thereby finds that group 3 should consist of Sc, Y, Lu, Lr.[56] The current IUPAC definition of the term "lanthanoid" includes fifteen elements including both lanthanum and lutetium, and that of "transition element"[57] applies to lanthanum and actinium, as well as lutetium but not lawrencium, since it does not correctly follow the Aufbau principle. Normally, the 103rd electron would enter the d-subshell, but quantum mechanical research has found that the configuration is actually [Rn]7s25f147p1[note 7] due to relativistic effects.[43][44] IUPAC thus has not recommended a specific format for the in-line-f-block periodic table, leaving the dispute open.

- Lanthanum and actinium are sometimes considered the remaining members of group 3.[58] In their most commonly encountered tripositive ion forms, these elements do not possess any partially filled f-orbitals, thus continuing the scandium—yttrium—lanthanum—actinium trend, in which all the elements have relationship similar to that of elements of the calcium—strontium—barium—radium series, the elements' left neighbors in s-block. However, different behavior is observed in other d-block groups, especially in group 4, in which zirconium, hafnium and rutherfordium share similar chemical properties lacking a clear trend. It has however been argued that this is irrelevant because the principle of increasing basicity down the table is more fundamental, and because the behavior of the group 3 elements is more similar to their s-block neighbors than their d-block neighbors.

- In other tables, lutetium and lawrencium are classified as the remaining members of group 3.[59] In these tables, lutetium and lawrencium end (or sometimes succeed) the lanthanide and actinide series, respectively. Since the f-shell is nominally full in the ground state electron configuration for both of these metals, they behave most similarly to other period 6 and period 7 transition metals compared to the other lanthanides and actinides, and thus logically exhibit properties similar to those of scandium and yttrium. However, this resemblance in not unique to lutetium and lawrencium, but is common among all the late lanthanides and actinides.

- Some tables, including the one published by IUPAC[60] refer to all lanthanides and actinides as being in group 3 resulting in 30 lanthanide and actinide elements together with scandium and yttrium. Lanthanides, as electropositive trivalent metals, all have a closely related chemistry, and all show many similarities to scandium and yttrium. Most of them also show additional properties characteristic of partially filled f-orbitals which are not common to scandium and yttrium.

- Exclusion of all elements is based on properties of earlier actinides, which show a much wider variety of chemistry (for instance, in range of oxidation states) within their series than the lanthanides, and comparisons to scandium and yttrium are even less useful.[61] However, these elements are destabilized,[62] and if they were stabilized to more closely match chemistry laws, they would be similar to lanthanides as well. Also, the later actinides from californium onwards behave more like the corresponding lanthanides, with only the valence +3 (and sometimes +2) shown.[61]

In 2015, IUPAC initiated a project to make a recommendation on the composition of group 3 as either:

- the elements Sc, Y, Lu and Lr, or

- the elements Sc, Y, La and Ac.[63]

The project is led by Eric Scerri. A structure with group 3 consisting of 32 elements (as older periodic tables show) is not being considered.

The La and Ac variant remains the most common in the literature, despite some calls for a change to the Lu and Lr variant. In terms of chemical behaviour,[64] and trends going down group 3 for properties such as melting point, electronegativity and ionic radius,[65][66] scandium, yttrium, lanthanum and actinium are similar to their group 1–2 counterparts. In this variant, the number of f electrons in the most common (trivalent) ions of the f-block elements consistently matches their position in the f-block.[67] For example, the f-electron counts for the trivalent ions of the first three f-block elements are Ce 1, Pr 2 and Nd 3.[68]

Occurrence

Scandium, yttrium, lanthanum, and lutetium tend to occur together with the other lanthanides (except promethium) in the Earth's crust, and are often harder to extract from their ores. The abundance of elements in Earth's crust for group 3 is quite low—all the elements in the group are uncommon, the most abundant being yttrium with abundance of approximately 30 parts per million (ppm); the abundance of scandium is 16 ppm, while that of lutetium is about 0.5 ppm. The abundance of lanthanum is greater, being about 35 ppm. For comparison, the abundance of copper is 50 ppm, that of chromium is 160 ppm, and that of molybdenum is 1.5 ppm.[58]

Scandium is distributed sparsely and occurs in trace amounts in many minerals.[69] Rare minerals from Scandinavia[70] and Madagascar[71] such as gadolinite, euxenite, and thortveitite are the only known concentrated sources of this element, the latter containing up to 45% of scandium in the form of scandium(III) oxide.[70] Yttrium has the same trend in occurrence places; it is found in lunar rock samples collected during the American Apollo Project in a relatively high content as well.[72]

The principal commercially viable ore of lutetium is the rare-earth phosphate mineral monazite, (Ce,La,etc.)PO4, which contains 0.003% of the element. The main mining areas are China, United States, Brazil, India, Sri Lanka and Australia. Pure lutetium metal is one of the rarest and most expensive of the rare-earth metals with the price about US$10,000/kg, or about one-fourth that of gold. Lanthanum is much more common, being the second most abundant rare earth, and in addition to monazite can also be extracted economically from bastnäsite.[73][74]

Production

The most available element in group 3 is yttrium, with annual production of 8,900 tonnes in 2010. Yttrium is mostly produced as oxide, by a single country, China (99%).[75] Lutetium and scandium are also mostly obtained as oxides, and their annual production by 2001 was about 10 and 2 tonnes, respectively.[76]

Group 3 elements are mined only as a byproduct from the extraction of other elements.[77] The metallic elements are extremely rare; the production of metallic yttrium is about a few tonnes, and that of scandium is in the order of 10 kg per year;[77][78] production of lutetium is not calculated, but it is certainly small. The elements, after purification from other rare-earth metals, are isolated as oxides; the oxides are converted to fluorides during reactions with hydrofluoric acid.[79] The resulting fluorides are reduced with alkaline earth metals or alloys of the metals; metallic calcium is used most frequently.[79] For example:

- Sc2O3 + 3 HF → 2 ScF3 + 3 H2O

- 2 ScF3 + 3 Ca → 3 CaF2 + 2 Sc

Biological chemistry

Group 3 elements are generally hard metals with low aqueous solubility, and have low availability to the biosphere. No group 3 element has any documented biological role in living organisms. The radioactivity of the actinides generally makes them highly toxic to living cells, causing radiation poisoning.

Scandium has no biological role, but it is found in living organisms. Once reached a human, scandium concentrates in the liver and is a threat to it; some its compounds are possibly carcinogenic, even through in general scandium is not toxic.[80] Scandium is known to have reached the food chain, but in trace amounts only; a typical human takes in less than 0.1 micrograms per day.[80] Once released into the environment, scandium gradually accumulates in soils, which leads to increased concentrations in soil particles, animals and humans. Scandium is mostly dangerous in the working environment, due to the fact that damps and gases can be inhaled with air. This can cause lung embolisms, especially during long-term exposure. The element is known to damage cell membranes of water animals, causing several negative influences on reproduction and on the functions of the nervous system.[80]

Yttrium has no known biological role, though it is found in most, if not all, organisms and tends to concentrate in the liver, kidney, spleen, lungs, and bones of humans.[81] There is normally as little as 0.5 milligrams found within the entire human body; human breast milk contains 4 ppm.[82] Yttrium can be found in edible plants in concentrations between 20 ppm and 100 ppm (fresh weight), with cabbage having the largest amount.[82] With up to 700 ppm, the seeds of woody plants have the highest known concentrations.[82]

Lutetium has no biological role as well, but it is found even in the highest known organism, the humans, concentrating in bones, and to a lesser extent in the liver and kidneys.[83] Lutetium salts are known to cause metabolism and they occur together with other lanthanide salts in nature; the element is the least abundant in the human body of all lanthanides.[83] Human diets have not been monitored for lutetium content, so it is not known how much the average human takes in, but estimations show the amount is only about several micrograms per year, all coming from tiny amounts taken by plants. Soluble lutetium salts are mildly toxic, but insoluble ones are not.[83] Lanthanum is not essential for humans and has a low to moderate level of toxicity. However, it is essential for the methanotrophic bacterium Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV, although the general similarity of the rare earths means that it may be substituted by some of the other early lanthanides with no ill effects.[84]

The high radioactivity of lawrencium would make it highly toxic to living cells, causing radiation poisoning. The same is true for actinium.

Notes

- Ytterbite was named after the village it was discovered near, plus the -ite ending to indicate it was a mineral.

- Earths were given an -a ending and new elements are normally given an -ium ending.

- Unpenttrium, according to calculations, should have an electronic configuration of [Og]8s25g186f117d28p1/22.[37]

- If lutetium and lawrencium are included instead, the table ends with the following lines:

Electron configurations of the group 3 elements Z Element Electron configuration 71 lutetium 2, 8, 18, 32, 9, 2 103 lawrencium 2, 8, 18, 32, 32, 8, 3 - If lutetium and lawrencium are included instead, the table ends with the following lines (the data for lawrencium is approximate):

Source: Lide, D. R., ed. (2003). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (84th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.Properties of the group 3 elements Name Lutetium Lawrencium Melting point 1925 K, 1652 °C ? 1900 K, ? 1627 °C Boiling point 3675 K, 3402 °C ? Density 9.84 g·cm−3 ? 16 g·cm−3 Appearance silver gray ? Atomic radius 174 pm ? - However, the group 12 elements are not always considered to be transition metals.

- The expected configuration of lawrencium if it did obey the Aufbau principle would be [Rn]7s25f146d1, with the normal incomplete 6d-subshell in the neutral state.

References

- van der Krogt, Peter. "39 Yttrium – Elementymology & Elements Multidict". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- Emsley 2001, p. 496

- Gadolin, Johan (1794). "Undersökning af en svart tung Stenart ifrån Ytterby Stenbrott i Roslagen". Kongl. Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar (in Swedish). 15: 137–155.

- Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 944. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- Coplen, Tyler B.; Peiser, H. S. (1998). "History of the Recommended Atomic-Weight Values from 1882 to 1997: A Comparison of Differences from Current Values to the Estimated Uncertainties of Earlier Values (Technical Report)". Pure Appl. Chem. IUPAC's Inorganic Chemistry Division Commission on Atomic Weights and Isotopic Abundances. 70 (1): 237–257. doi:10.1351/pac199870010237.

- Heiserman, David L. (1992). "Element 39: Yttrium". Exploring Chemical Elements and their Compounds. New York: TAB Books. pp. 150–152. ISBN 0-8306-3018-X.

- Wöhler, Friedrich (1828). "Über das Beryllium und Yttrium". Annalen der Physik (in German). 89 (8): 577–582. Bibcode:1828AnP....89..577W. doi:10.1002/andp.18280890805.

- Ball, Philip (2002). The Ingredients: A Guided Tour of the Elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 100–102. ISBN 0-19-284100-9.

- Nilson, Lars Fredrik (1879). "Sur l'ytterbine, terre nouvelle de M. Marignac". Comptes Rendus (in French). 88: 642–647.

- Nilson, Lars Fredrik (1879). "Ueber Scandium, ein neues Erdmetall". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 12 (1): 554–557. doi:10.1002/cber.187901201157.

- Cleve, Per Teodor (1879). "Sur le scandium". Comptes Rendus (in French). 89: 419–422.

- Fischer, Werner; Brünger, Karl; Grieneisen, Hans (1937). "Über das metallische Scandium". Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie (in German). 231 (1–2): 54–62. doi:10.1002/zaac.19372310107.

- "The Discovery and Naming of the Rare Earths". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1424

- Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The Discovery of the Elements: XI. Some Elements Isolated with the Aid of Potassium and Sodium:Zirconium, Titanium, Cerium and Thorium". The Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (7): 1231–1243. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9.1231W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1231.

- See:

- (Berzelius) (1839) "Nouveau métal" (New metal), Comptes rendus, 8 : 356–357. From p. 356: "L'oxide de cérium, extrait de la cérite par la procédé ordinaire, contient à peu près les deux cinquièmes de son poids de l'oxide du nouveau métal qui ne change que peu les propriétés du cérium, et qui s'y tient pour ainsi dire caché. Cette raison a engagé M. Mosander à donner au nouveau métal le nom de Lantane." (The oxide of cerium, extracted from cerite by the usual procedure, contains almost two fifths of its weight in the oxide of the new metal, which differs only slightly from the properties of cerium, and which is held in it so to speak "hidden". This reason motivated Mr. Mosander to give to the new metal the name Lantane.)

- (Berzelius) (1839) "Latanium — a new metal," Philosophical Magazine, new series, 14 : 390–391.

- Patnaik, Pradyot (2003). Handbook of Inorganic Chemical Compounds. McGraw-Hill. pp. 444–446. ISBN 0-07-049439-8. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- Urbain, M. G. (1908). "Un nouvel élément, le lutécium, résultant du dédoublement de l'ytterbium de Marignac". Comptes rendus (in French). 145: 759–762.

- "Separation of Rare Earth Elements by Charles James". National Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- von Welsbach; Carl Auer (1908). "Die Zerlegung des Ytterbiums in seine Elemente". Monatshefte für Chemie (in German). 29 (2): 181–225. doi:10.1007/BF01558944.

- Urbain, G. (1909). "Lutetium und Neoytterbium oder Cassiopeium und Aldebaranium – Erwiderung auf den Artikel des Herrn Auer v. Welsbach". Monatshefte für Chemie (in German). 31 (10): I. doi:10.1007/BF01530262.

- Clarke, F. W.; Ostwald, W.; Thorpe, T. E.; Urbain, G. (1909). "Bericht des Internationalen Atomgewichts-Ausschusses für 1909". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 42 (1): 11–17. doi:10.1002/cber.19090420104.

- van der Krogt, Peter. "70. Ytterbium – Elementymology & Elements Multidict". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- van der Krogt, Peter. "71. Lutetium – Elementymology & Elements Multidict". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Emsley, John (2001). Nature's building blocks: an A-Z guide to the elements. US: Oxford University Press. pp. 240–242. ISBN 0-19-850341-5.

- Debierne, André-Louis (1899). "Sur un nouvelle matière radio-active". Comptes rendus (in French). 129: 593–595.

- Debierne, André-Louis (1900–1901). "Sur un nouvelle matière radio-actif – l'actinium". Comptes rendus (in French). 130: 906–908.

- Giesel, Friedrich Oskar (1902). "Ueber Radium und radioactive Stoffe". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 35 (3): 3608–3611. doi:10.1002/cber.190203503187.

- Giesel, Friedrich Oskar (1904). "Ueber den Emanationskörper (Emanium)". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 37 (2): 1696–1699. doi:10.1002/cber.19040370280.

- Debierne, André-Louis (1904). "Sur l'actinium". Comptes rendus (in French). 139: 538–540.

- Giesel, Friedrich Oskar (1904). "Ueber Emanium". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 37 (2): 1696–1699. doi:10.1002/cber.19040370280.

- Giesel, Friedrich Oskar (1905). "Ueber Emanium". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 38 (1): 775–778. doi:10.1002/cber.190503801130.

- Ghiorso, Albert; Sikkeland, T.; Larsh, A. E.; Latimer, R. M. (1961). "New Element, Lawrencium, Atomic Number 103" (PDF). Phys. Rev. Lett. 6 (9): 473. Bibcode:1961PhRvL...6..473G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.6.473.

- Flerov, G. N. (1967). "On the nuclear properties of the isotopes 256103 and 257103". Nucl. Phys. A. 106 (2): 476. Bibcode:1967NuPhA.106..476F. doi:10.1016/0375-9474(67)90892-5.

- Donets, E. D.; Shchegolev, V. A.; Ermakov, V. A. (1965). "Synthesis of the isotope of element 103 (lawrencium) with mass number 256". Atomnaya Énergiya (in Russian). 19 (2): 109.

- Translated in Donets, E. D.; Shchegolev, V. A.; Ermakov, V. A. (1965). "Synthesis of the isotope of element 103 (lawrencium) with mass number 256". Soviet Atomic Energy. 19 (2): 109. doi:10.1007/BF01126414.

- Greenwood, Norman N. (1997). "Recent developments concerning the discovery of elements 101–111". Pure Appl. Chem. 69 (1): 179–184. doi:10.1351/pac199769010179.

- Hoffman, Darleane C.; Lee, Diana M.; Pershina, Valeria (2006). "Transactinides and the future elements". In Morss; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 1-4020-3555-1.

- Pyykkö, Pekka (2011). "A suggested periodic table up to Z ≤ 172, based on Dirac–Fock calculations on atoms and ions". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 13 (1): 161–8. Bibcode:2011PCCP...13..161P. doi:10.1039/c0cp01575j. PMID 20967377.

- Nefedov, V.I.; Trzhaskovskaya, M.B.; Yarzhemskii, V.G. (2006). "Electronic Configurations and the Periodic Table for Superheavy Elements" (PDF). Doklady Physical Chemistry. 408 (2): 149–151. doi:10.1134/S0012501606060029. ISSN 0012-5016.

- Hofmann, Sigurd (2002). On Beyond Uranium. Taylor & Francis. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-415-28496-7.

- Roberto, J. B. (31 March 2015). "Actinide Targets for Super-Heavy Element Research" (PDF). cyclotron.tamu.edu. Texas A & M University. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- van der Krogt, Peter. "Elementymology & Elements Multidict". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Eliav, E.; Kaldor, U.; Ishikawa, Y. (1995). "Transition energies of ytterbium, lutetium, and lawrencium by the relativistic coupled-cluster method". Phys. Rev. A. 52 (1): 291–296. Bibcode:1995PhRvA..52..291E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.52.291. PMID 9912247.

- Zou, Yu; Froese, Fischer C. (2002). "Resonance Transition Energies and Oscillator Strengths in Lutetium and Lawrencium". Phys. Rev. Lett. 88 (18): 183001. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88b3001M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.023001. PMID 12005680.

- Corbett, J. D. (1981). "Extended metal-metal bonding in halides of the early transition metals". Acc. Chem. Res. 14 (8): 239–246. doi:10.1021/ar00068a003.

- Nikolai B., Mikheev; Auerman, L. N.; Rumer, Igor A.; Kamenskaya, Alla N.; Kazakevich, M. Z. (1992). "The anomalous stabilisation of the oxidation state 2+ of lanthanides and actinides". Russian Chemical Reviews. 61 (10): 990–998. Bibcode:1992RuCRv..61..990M. doi:10.1070/RC1992v061n10ABEH001011.

- Kang, Weekyung; Bernstein, E. R. (2005). "Formation of Yttrium Oxide Clusters Using Pulsed Laser Vaporization". Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 26 (2): 345–348. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2005.26.2.345. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- Cotton, S. A. (1994). "Scandium, Yttrium and the Lanthanides: Inorganic and Coordination Chemistry". Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-93620-0.

- Dean, John A. (1999). Lange's handbook of chemistry (Fifteenth edition). McGraw-Hill, Inc. pp. 589–592. ISBN 0-07-016190-9.

- Barbalace, Kenneth. "Periodic Table of Elements Sorted by Melting Point". Environmental Chemistry.com. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- Barbalace, Kenneth. "Periodic Table of Elements Sorted by Boiling Point". Environmental Chemistry.com. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- Fournier, Jean-Marc (1976). "Bonding and the electronic structure of the actinide metals". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 37 (2): 235–244. Bibcode:1976JPCS...37..235F. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(76)90167-0.

- Penneman, R. A.; Mann, J. B. (1976). "'Calculation chemistry' of the superheavy elements; comparison with elements of the 7th period". Proceedings of the Moscow Symposium on the Chemistry of Transuranium Elements: 257–263. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-020638-7.50053-1.

- Barbalace, Kenneth. "Scandium". Chemical Book. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- Barbalace, Kenneth. "Yttrium". Chemical Book. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- Scerri, Eric (2012). "Mendeleev's Periodic Table Is Finally Completed and What To Do about Group ?". Chem. Int. 34 (4): 28–31. doi:10.1515/ci.2012.34.4.28.

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "transition element". doi:10.1351/goldbook.T06456

- Barbalace, Kenneth. "Periodic Table of Elements". Environmental Chemistry.com. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- "WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements". Webelements.com. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- "Periodic Table of the Elements". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- "Visual Elements". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Dolg, Michael. "Lanthanides and Actinides" (PDF). Max-Planck-Institut für Physik komplexer Systeme, Dresden, Germany. CLA01. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- IUPAC (2015). "The constitution of group 3 of the periodic table". Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- Greenwood, N. N.; Harrington, T. J. (1973). The chemistry of the transition elements. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-19-855435-4.

- Aylward, G.; Findlay, T. (2008). SI chemical data (6th ed.). Milton, Queensland: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-81638-7.

- Wiberg, N. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- Wulfsberg, G. (2006). "Periodic table: Trends in the properties of the elements". Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-470-86210-0.

- Cotton, S. (2007). Lanthanide and Actinide Chemistry. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-470-01006-8.

- Bernhard, F. (2001). "Scandium mineralization associated with hydrothermal lazurite-quartz veins in the Lower Austroalpie Grobgneis complex, East Alps, Austria". Mineral Deposits in the Beginning of the 21st Century. Lisse: Balkema. ISBN 90-265-1846-3.

- Kristiansen, Roy (2003). "Scandium – Mineraler I Norge" (PDF). Stein (in Norwegian): 14–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2010.

- von Knorring, O.; Condliffe, E. (1987). "Mineralized pegmatites in Africa". Geological Journal. 22: 253. doi:10.1002/gj.3350220619.

- Stwertka, Albert (1998). "Yttrium". Guide to the Elements (Revised ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 0-19-508083-1.

- Hedrick, James B. "Rare-Earth Metals" (PDF). USGS. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- Castor, Stephen B.; Hedrick, James B. "Rare Earth Elements" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2010: Yttrium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- Emsley 2001, p. 241

- Deschamps, Y. "Scandium" (PDF). mineralinfo.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2010: Scandium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1056–1057. ISBN 3-11-007511-3.

- Lenntech (1998). "Scandium (Sc) — chemical properties of scandium, health effects of scandium, environmental effects of scandium". Lenntech. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- MacDonald, N. S.; Nusbaum, R. E.; Alexander, G. V. (1952). "The Skeletal Deposition of Yttrium" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 195 (2): 837–841. PMID 14946195.

- Emsley 2001, pp. 495–498

- Emsley 2001, p. 240

- Pol, Arjan; Barends, Thomas R. M.; Dietl, Andreas; Khadem, Ahmad F.; Eygensteyn, Jelle; Jetten, Mike S. M.; Op Den Camp, Huub J. M. (2013). "Rare earth metals are essential for methanotrophic life in volcanic mudpots". Environmental Microbiology. 16 (1): 255–64. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12249. PMID 24034209.

Bibliography

- Emsley, John (2001). Nature's building blocks: an A-Z guide to the elements. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850341-5.