Golden rice

Golden rice is a variety of rice (Oryza sativa) produced through genetic engineering to biosynthesize beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A, in the edible parts of rice.[1][2] It is intended to produce a fortified food to be grown and consumed in areas with a shortage of dietary vitamin A, a deficiency which each year is estimated to kill 670,000 children under the age of 5[3] and cause an additional 500,000 cases of irreversible childhood blindness.[4] Rice is a staple food crop for over half of the world's population, providing 30–72% of the energy intake for people in Asian countries, and becoming an effective crop for targeting vitamin deficiencies.[5]

| Golden rice | |

|---|---|

Golden rice (right) compared to white rice (left) | |

| Species | Oryza sativa |

| Cultivar | Golden rice |

| Origin | Rockefeller Foundation |

Golden rice differs from its parental strain by the addition of three beta-carotene biosynthesis genes. The parental strain can naturally produce beta-carotene in its leaves, where it is involved in photosynthesis. However, the plant does not normally produce the pigment in the endosperm, where photosynthesis does not occur. Golden rice has met significant opposition from environmental and anti-globalization activists. A study in the Philippines is aimed to evaluate the performance of golden rice, whether it can be planted, grown and harvested like other rice varieties, and whether golden rice poses risk to human health.[6] There has been little research on how well the beta-carotene will hold up when stored for long periods between harvest seasons, or when cooked using traditional methods.[7]

In 2005, Golden Rice 2 was announced, which produces up to 23 times as much beta-carotene as the original golden rice.[8] To receive the USDA's Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA), it is estimated that 144 g/day of the high-yielding strain would have to be eaten. Bioavailability of the carotene from golden rice has been confirmed and found to be an effective source of vitamin A for humans.[9][10][11] Golden Rice was one of the seven winners of the 2015 Patents for Humanity Awards by the United States Patent and Trademark Office.[12][13] In 2018 came the first approvals as food in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US.[14]

History

The search for a golden rice started off as a Rockefeller Foundation initiative in 1982.[15]

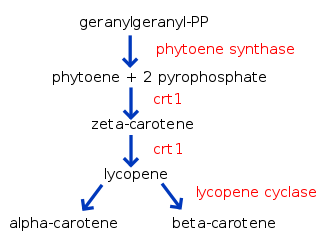

Peter Bramley discovered in the 1990s that a single phytoene desaturase gene (bacterial CrtI) can be used to produce lycopene from phytoene in GM tomato, rather than having to introduce multiple carotene desaturases that are normally used by higher plants.[16] Lycopene is then cyclized to beta-carotene by the endogenous cyclase in golden rice.[17]

The scientific details of the rice were first published in Science in 2000,[2] the product of an eight-year project by Ingo Potrykus of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and Peter Beyer of the University of Freiburg. At the time of publication, golden rice was considered a significant breakthrough in biotechnology, as the researchers had engineered an entire biosynthetic pathway.

The first field trials of golden rice cultivars were conducted by Louisiana State University Agricultural Center in 2004.[18] Additional trials have been conducted in the Philippines and Taiwan, and in Bangladesh (2015).[19] Field testing provides an accurate measurement of nutritional value and enables feeding tests to be performed. Preliminary results from field tests have shown field-grown golden rice produces 4 to 5 times more beta-carotene than golden rice grown under greenhouse conditions.[20]

Crossbreeding

In several countries, golden rice has been bred with local rice cultivars.[21] or crossbred with the American rice cultivar 'Cocodrie'.[18] As of March 2016, golden rice has not yet been grown commercially, and backcrossing is still ongoing in current varieties to reduce yield drag.[22][23]

Golden Rice 2

In 2005, a team of researchers at Syngenta produced Golden Rice 2. They combined the phytoene synthase gene from maize with crt1 from the original golden rice. Golden rice 2 produces 23 times more carotenoids than golden rice (up to 37 µg/g), and preferentially accumulates beta-carotene (up to 31 µg/g of the 37 µg/g of carotenoids).[8]

Approvals

In 2018, Canada and the United States approved golden rice for cultivation, with Health Canada and the US Food and Drug Administration declaring it safe for consumption.[24] This followed a 2016 decision where the US Food and Drug Administration had ruled that the beta-carotene content in golden rice did not provide sufficient amounts of Vitamin A to make a nutritional claim.[25] Health Canada declared that golden rice would not affect allergies, and that the nutrient contents of golden rice were the same as in common rice varieties, except for the intended high levels of provitamin A.[26] In 2019, it was approved for direct use as human food and animal feed or for processing in the Philippines.[27] This does not constitute approval for commercial propagation in the Philippines, which is a separate stage that remains to be completed.

Genetics

Golden rice was created by transforming rice with two beta-carotene biosynthesis genes:

- psy (phytoene synthase) from daffodil ('Narcissus pseudonarcissus')

- crtI (phytoene desaturase) from the soil bacterium Erwinia uredovora

(The insertion of a lcy (lycopene cyclase) gene was thought to be needed, but further research showed it is already produced in wild-type rice endosperm.)

The psy and crtI genes were transferred into the rice nuclear genome and placed under the control of an endosperm-specific promoter, so that they are only expressed in the endosperm. The exogenous lcy gene has a transit peptide sequence attached, so it is targeted to the plastid, where geranylgeranyl diphosphate is formed. The bacterial crtI gene was an important inclusion to complete the pathway, since it can catalyze multiple steps in the synthesis of carotenoids up to lycopene, while these steps require more than one enzyme in plants.[28] The end product of the engineered pathway is lycopene, but if the plant accumulated lycopene, the rice would be red. Recent analysis has shown the plant's endogenous enzymes process the lycopene to beta-carotene in the endosperm, giving the rice the distinctive yellow color for which it is named.[29] The original golden rice was called SGR1, and under greenhouse conditions it produced 1.6 µg/g of carotenoids.

Vitamin A deficiency

The research that led to golden rice was conducted with the goal of helping children who suffer from vitamin A deficiency (VAD). In 2005, 190 million children and 19 million pregnant women, in 122 countries, were estimated to be affected by VAD.[30] VAD is responsible for 1–2 million deaths, 500,000 cases of irreversible blindness and millions of cases of xerophthalmia annually.[4] Children and pregnant women are at highest risk. Vitamin A is supplemented orally and by injection in areas where the diet is deficient in vitamin A.

As of 1999, 43 countries had vitamin A supplementation programs for children under 5; in 10 of these countries, two high dose supplements are available per year, which, according to UNICEF, could effectively eliminate VAD.[31] However, UNICEF and a number of NGOs involved in supplementation note more frequent low-dose supplementation is preferable.[32]

Because many children in VAD-affected countries rely on rice as a staple food, genetic modification to make rice produce the vitamin A precursor beta-carotene was seen as a simple and less expensive alternative to ongoing vitamin supplements or an increase in the consumption of green vegetables or animal products. Initial analyses of the potential nutritional benefits of golden rice suggested consumption of golden rice would not eliminate the problems of vitamin A deficiency, but could complement other supplementation.[33][34] Golden Rice 2 contains sufficient provitamin A to provide the entire dietary requirement via daily consumption of some 75g per day.[8]

Since carotenes are hydrophobic, sufficient fat must be present in the diet for golden rice (or most other vitamin A supplements) to alleviate vitamin A deficiency. Vitamin A deficiency is usually coupled to an unbalanced diet (see also Vandana Shiva's arguments below). Moreover, this claim referred to an early cultivar of golden rice; one bowl of the latest version provides 60% of RDA for healthy children.[35] The RDA levels advocated in developed countries are far in excess of the amounts needed to prevent blindness.[8]

Research

Clinical trials/food safety and nutrition research

In 2009, results of a clinical trial of golden rice with adult volunteers from the US were published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. The trial concluded that "beta-carotene derived from golden rice is effectively converted to vitamin A in humans".[36] A summary for the American Society for Nutrition suggested that "Golden Rice could probably supply 50% of the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of vitamin A from a very modest amount – perhaps a cup – of rice, if consumed daily. This amount is well within the consumption habits of most young children and their mothers".[37]

It is well known that beta-carotene is found and consumed in many nutritious foods eaten around the world, including fruits and vegetables. Beta-carotene in food is a safe source of vitamin A.[38] In August 2012, Tufts University and others published research on golden rice in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition showing that the beta-carotene produced by golden rice is as effective as beta-carotene in oil at providing vitamin A to children.[39] The study stated that "recruitment processes and protocol were approved".[39][40] In 2015 the journal retracted the study, claiming that the researchers had acted unethically when providing Chinese children golden rice without their parents' consent.[41][42]

The Food Allergy Resource and Research Program of the University of Nebraska undertook research in 2006 that showed the proteins from the new genes in Golden Rice 2 showed no allergenic properties.[43]

Controversy

Critics of genetically engineered crops have raised various concerns. An early issue was that golden rice originally did not have sufficient provitamin A content. This problem was solved by the development of new strains of rice.[8] The speed at which beta-carotene degrades once the rice is harvested, and how much remains after cooking are contested.[44] However, a 2009 study concluded that beta-carotene from golden rice is effectively converted into vitamin A in humans[9] and a 2012 study that fed 68 children ages 6 to 8 concluded that golden rice was as good as vitamin A supplements and better than the natural beta-carotene in spinach.[11]

Greenpeace opposes the use of any patented genetically modified organisms in agriculture and opposes the cultivation of golden rice, claiming it will open the door to more widespread use of GMOs.[45][46] The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) has emphasised the non-commercial nature of their project, stating that "None of the companies listed ... are involved in carrying out the research and development activities of IRRI or its partners in Golden Rice, and none of them will receive any royalty or payment from the marketing or selling of golden rice varieties developed by IRRI."[47]

Vandana Shiva, an Indian anti-GMO activist, argued the problem was not the plant per se, but potential problems with poverty and loss of biodiversity. Shiva claimed these problems could be amplified by the corporate control of agriculture. By focusing on a narrow problem (vitamin A deficiency), Shiva argued, golden rice proponents were obscuring the limited availability of diverse and nutritionally adequate food.[48] Other groups argued that a varied diet containing foods rich in beta-carotene such as sweet potato, leaf vegetables and fruit would provide children with sufficient vitamin A.[49] Keith West of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health has stated that foodstuffs containing vitamin A are often unavailable, only available at certain seasons, or too expensive for poor families in underdeveloped countries.[11]

In 2008, WHO malnutrition expert Francesco Branca cited the lack of real-world studies and uncertainty about how many people will use golden rice, concluding "giving out supplements, fortifying existing foods with vitamin A, and teaching people to grow carrots or certain leafy vegetables are, for now, more promising ways to fight the problem".[50] In 2013, author Michael Pollan, who had critiqued the product in 2001, unimpressed by the benefits, expressed support for the continuation of the research.[51]

In 2012, controversy surrounded a study published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. The study, involving feeding GM rice to 6 to 8 year old children in China, was later found to have violated human research rules of both Tufts University and the federal government. Subsequent reviews found no evidence of safety problems with the study, but found issues with insufficient consent forms, unapproved changes to study protocol, and lack of approval from a China-based ethics review board. Additionally, the GM rice used was brought into China illegally.[52][53]

Support

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation supports the use of genetically modified organisms in agricultural development and supports the International Rice Research Institute in developing golden rice.[54] In June 2016, 107 Nobel laureates signed a letter urging Greenpeace and its supporters to abandon their campaign against GMOs, and against golden rice in particular.[55][56]

In May 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of golden rice for human consumption, stating: "Based on the information IRRI has presented to FDA, we have no further questions concerning human or animal food derived from GR2E rice at this time."[14] This marks the fourth national health organisation to approve the use of golden rice in 2018, joining Australia, Canada and New Zealand who issued their assessments earlier in the year.[57]

Protests

On August 8, 2013, an experimental plot of golden rice being developed at IRRI in the Philippines was uprooted by protesters.[35][51][58] British author Mark Lynas reported in Slate that the vandalism was carried out by a group of activists led by the extreme left-inclined Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP) (unofficial translation: Farmers' Movement of the Philippines), to the dismay of other protesters.[51][59] No local farmers participated in the uprooting; only the small number of activists damaged the golden rice crops.[60]

Distribution

A recommendation was made that golden rice to be distributed free to subsistence farmers.[61] Free licenses for developing countries were granted quickly due to the positive publicity that golden rice received, particularly in Time magazine in July 2000.[62] Monsanto Company was one of the companies to grant free licences for related patents owned by the company.[63] The cutoff between humanitarian and commercial use was set at US$10,000. Therefore, as long as a farmer or subsequent user of golden rice genetics would not make more than $10,000 per year, no royalties would need to be paid. In addition, farmers would be permitted to keep and replant seed.[64]

See also

References

- Kettenburg, Annika J.; Hanspach, Jan; Abson, David J.; Fischer, Joern (2018-05-17). "From disagreements to dialogue: unpacking the Golden Rice debate". Sustainability Science. 13 (5): 1469–82. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0577-y. ISSN 1862-4065. PMC 6132390. PMID 30220919.

- Ye, X; Al-Babili, S; Klöti, A; Zhang, J; Lucca, P; Beyer, P; Potrykus, I (2000). "Engineering the provitamin A (beta-carotene) biosynthetic pathway into (carotenoid-free) rice endosperm". Science. 287 (5451): 303–05. Bibcode:2000Sci...287..303Y. doi:10.1126/science.287.5451.303. PMID 10634784.

- Black RE et al., Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences, The Lancet, 2008, 371(9608), p. 253.

- Humphrey, J.H.; West, K.P. Jr; Sommer, A. (1992). "Vitamin A deficiency and attributable mortality in under-5-year-olds" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 70 (2): 225–32. PMC 2393289. PMID 1600583.

- Datta, K; Sahoo, G; Krishnan, S; Ganguly, M; Datta, SK (2014). "Genetic Stability Developed for β-Carotene Synthesis in BR29 Rice Line Using Dihaploid Homozygosity". PLoS ONE. 9 (6): e100212. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j0212D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100212. PMC 4061092. PMID 24937154.

- PhilRice Two seasons of Golden Rice trials in Phl concluded, 09 June 2013.

- "Genetically modified Golden Rice falls short on lifesaving promises | The Source | Washington University in St. Louis". The Source. 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- Paine, Jacqueline A; Shipton, Catherine A; Chaggar, Sunandha; Howells, Rhian M; Kennedy, Mike J; Vernon, Gareth; Wright, Susan Y; Hinchliffe, Edward; Adams, Jessica L (2005). "Improving the nutritional value of Golden Rice through increased pro-vitamin A content". Nature Biotechnology. 23 (4): 482–87. doi:10.1038/nbt1082. PMID 15793573.

- Tang, G; Qin, J; Dolnikowski, GG; Russell, RM; Grusak, MA (2009). "Golden Rice is an effective source of vitamin A". Am J Clin Nutr. 89 (6): 1776–83. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27119. PMC 2682994. PMID 19369372.

- Datta, S.K.; Datta, Karabi; Parkhi, Vilas; Rai, Mayank; Baisakh, Niranjan; Sahoo, Gayatri; Rehana, Sayeda; Bandyopadhyay, Anindya; Alamgir, Md. (2007). "Golden rice: introgression, breeding, and field evaluation". Euphytica. 154 (3): 271–78. doi:10.1007/s10681-006-9311-4.

- Norton, Amy (15 August 2012) Genetically modified rice a good vitamin A source Reuters, Retrieved 20 August 2012

- "Patents for Humanity Awards 2015". United States Patent and Trademark Office.

- "Patents for Humanity Awards Ceremony at the White House". IP Watchdog Blog. 20 April 2015.

- "US FDA approves GMO Golden Rice as safe to eat | Genetic Literacy Project". geneticliteracyproject.org. Retrieved 2018-05-30.

- FAQ: Who invented Golden Rice and how did the project start? Goldenrice.org.

- Romer, S.; Fraser, P.D.; Kiano, J.W.; Shipton, C.A.; Misawa, N; Schuch, W.; Bramley, P.M. (2000). "Elevation of provitamin A content of transgenic tomato plants". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (6): 666–69. doi:10.1038/76523. PMID 10835607.

- "The Science of Golden Rice". Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- LSU AgCenter Communications (2004). "'Golden Rice' Could Help Reduce Malnutrition". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- Ahmad, Reaz (8 October 2015). "Bangladeshi scientists ready for trial of world's first 'Golden Rice'". The Daily Star. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- "Testing the performance of Golden Rice". Goldenrice.org. 2012-08-29. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- Watson, Todd (10 August 2013). "GM rice field destroyed by activists in the Philippines". Inside Investor. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- Everding, Gerry (June 2, 2016). "Genetically modified golden rice falls short on lifesaving promises". The Source.

- Philpott, Tom (3 February 2016). "WTF Happened to Golden Rice?". Mother Jones. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Coghlan, Andy (May 30, 2018). "GM golden rice gets approval from food regulators in the US". New Scientist. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- "Consultations on Food from New Plant Varieties". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- "Provitamin A biofortified rice event GR2E (golden rice)". Health Canada, Government of Canada. 16 March 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Philippines approves Golden Rice for direct use as food and feed, or for processing". International Rice Research Institute. 18 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Hirschberg, J. (2001). "Carotenoid biosynthesis in flowering plants". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 4 (3): 210–18. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00163-1. PMID 11312131.

- Schaub, P.; Al-Babili, S; Drake, R; Beyer, P (2005). "Why Is Golden Rice Golden (Yellow) Instead of Red?". Plant Physiology. 138 (1): 441–50. doi:10.1104/pp.104.057927. PMC 1104197. PMID 15821145.

- Staff (2009) Global Prevalence Of Vitamin A Deficiency in Populations At Risk 1995–2005 WHO Global Database on Vitamin A Deficiency. Geneva, World Health Organization, ISBN 978-92-4-159801-9, Retrieved 10 October 2011

- UNICEF. Vitamin A deficiency

- Vitamin A Global Initiative. 1997. A Strategy for Acceleration of Progress in Combating Vitamin A Deficiency

- Dawe, D.; Robertson, R.; Unnevehr, L. (2002). "Golden rice: what role could it play in alleviation of vitamin A deficiency?". Food Policy. 27 (5–6): 541–60. doi:10.1016/S0306-9192(02)00065-9.

- Zimmerman, R.; Qaim, M. (2004). "Potential health benefits of Golden Rice: a Philippine case study". Food Policy. 29 (2): 147–68. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2004.03.001. Archived from the original on 2009-01-06. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Amy Harmon (August 24, 2013). "Golden Rice: Lifesaver?" (News Analysis). The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- Golden Rice is an effective source of vitamin A, by Guangwen Tang, Jian Qin, Gregory G Dolnikowski, Robert M Russell, and Michael A Grusak in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2009; 89:1776–83.

- American Society of Nutrition: Researchers Determine That Golden Rice Is an Effective Source of Vitamin A

- β-Carotene Is an Important Vitamin A Source for Humans. J. Nutr. December 1, 2010 vol. 140 no. 12 2268S–85S

- Guangwen Tang, Yuming Hu, Shi-an Yin, Yin Wang, Gerard E Dallal, Michael A Grusak, and Robert M Russell β-Carotene in Golden Rice is as good as β-Carotene in oil at providing vitamin A to children Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 96:658–64.

- "China continues to probe alleged GM rice testing". Globaltimes.cn. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Sep; 102(3):715. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.093229. Epub 2015 Jul 29. "Retraction of Tang G, Hu Y, Yin S-a, Wang Y, Dallal GE, Grusak MA, and Russell RM. β-Carotene in Golden Rice is as good as β-carotene in oil at providing vitamin A to children. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 96:658–64".

- BostonGlobe (2015). "Ethics in question, Tufts researcher's paper retracted".

- Goodman RE, Wise J. Bioinformatic analysis of proteins in Golden Rice 2 to assess potential allergenic cross-reactivity. Preliminary Report. University of Nebraska. Food Allergy Research and Resource Program. May 2, 2006.

- Then, C, 2009, "The campaign for genetically modified rice is at the crossroads: A critical look at Golden Rice after nearly 10 years of development." Foodwatch in Germany

- "Genetic Engineering". Greenpeace.

"Golden Rice: All glitter, no gold". Greenpeace. March 16, 2005. - Greenpeace. 2005. All that Glitters is not Gold: The False Hope of Golden Rice Archived 2013-08-01 at the Wayback Machine

- IRRI. 2014. FAQ: Are private companies involved in the Golden Rice project?

- "The "Golden Rice" Hoax – When Public Relations replaces Science". Online.sfsu.edu. 2000-06-29. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- Friends of the Earth. Golden Rice and Vitamin A Deficiency Archived 2016-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Enserink, M. (2008). "Tough Lessons From Golden Rice". Science. 320 (5875): 468–71. doi:10.1126/science.320.5875.468. PMID 18436769.

- Andrew Revkin (2013-09-01). "From Lynas to Pollan, Agreement that Golden Rice Trials Should Proceed". The New York Times.

- Enserink, Martin (18 September 2013). "Golden Rice Not So Golden for Tufts". Science Magazine. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Qiu, Jane (10 December 2012). "China sacks officials over Golden Rice controversy". Nature. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Agricultural Development Golden Rice". Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 3 Feb 2016.

- "Laureates Letter Supporting Precision Agriculture (GMOs)". Retrieved 5 Jul 2016.

- Achenbach, Joel (2016-06-30). "107 Nobel laureates sign letter blasting Greenpeace over GMOs". Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

- "Golden Rice meets food safety standards in three global leading regulatory agencies". International Rice Research Institute – IRRI. Retrieved 2018-05-30.

- Michael Slezak (August 9, 2013). "Militant Filipino farmers destroy Golden Rice GM crop". NewScientist. Retrieved Oct 26, 2013.

- The True Story About Who Destroyed a Genetically Modified Rice Crop, Mark Lynas, Slate, Aug 26, 2013

- "Golden rice attack in Philippines: Anti-GMO activists lie about protest and safety". Slate Magazine.

- Potrykus, I. (2001). "Golden Rice and Beyond". Plant Physiology. 125 (3): 1157–61. doi:10.1104/pp.125.3.1157. PMC 1539367. PMID 11244094.

- "This Rice Could Save a Million Kids a Year". 2000-07-31. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- Dobson, Roger (2000), "Royalty-free licenses for genetically modified rice made available to developing countries", Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78 (10): 1281, PMC 2560613, PMID 11100623.

- "Golden Rice Project". Frequently asked questions. Golden rice. 2004-10-13. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Golden rice. |