Germans

Germans (German: Deutsche) are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe,[27][28][29][30] who share a common German ancestry, culture, and history. German is the shared mother tongue of a substantial majority of ethnic Germans.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 100–150 worldwide[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 62,482,000[2] | |

| 46,047,114 (descent)[3] | |

| 12,000,000 (descent)[4][5] | |

| 3,541,600 (descent)[6] | |

| 3,322,405 (descent)[7] | |

| 500,000 (descent)[8] | |

| 437,000[9] | |

| 394,138 | |

| 368,512[10] | |

| 310,900[11] | |

| 204,000[12] | |

| 181,958[13] | |

| 178,837[14] | |

| 148,000[15] | |

| 167,771 [16] | |

| 50,863 | |

| 15,000–40,000[17] | |

| 40,000[18] | |

| 36,000[19] | |

| 33,302[20] | |

| 27,593[21][22] | |

| 25,000[23] | |

| 21,216[24] | |

| 10,030 (2016)[25] | |

| Languages | |

| German | |

| Religion | |

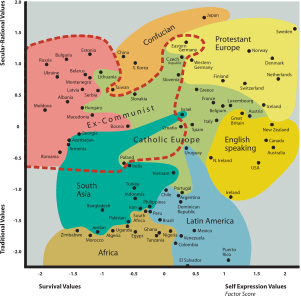

| Historically: 2/3rds Protestant[note 1] 1/3rd Roman Catholic Nowadays: 1/3rd Protestant[note 2][26] 1/3rd Roman Catholic 1/3rd Irreligious | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Germanic peoples | |

The English term Germans has historically referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages.[note 3] Ever since the outbreak of the Protestant Reformation within the Holy Roman Empire, German society has been characterized by a Catholic-Protestant divide.[31]

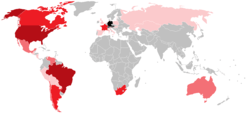

Of approximately 100 million native speakers of German in the world,[32] roughly 80 million consider themselves Germans. There are an additional 80 million people of German ancestry mainly in the United States, Brazil (mainly in the South Region of the country), Argentina, Canada, South Africa, the post-Soviet states (mainly in Russia and Kazakhstan), and France, each accounting for at least 1 million.[note 4] Thus, the total number of Germans lies somewhere between 100 and more than 150 million, depending on the criteria applied[1] (native speakers, single-ancestry ethnic Germans, partial German ancestry, etc.).

Today, people from countries with German-speaking majorities which were earlier part of the Holy Roman Empire, (such as Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and other historically-tied countries like Luxembourg), most often subscribe to their own national identities and may or may not also self-identify as ethnically German.[33]

Etymology

The German term Deutsche originates from the Old High German word diutisc (from diot "people"), referring to the Germanic "language of the people". It is not clear how commonly, if at all, the word was used as an ethnonym in Old High German.

Used as a noun, ein diutscher in the sense of "a German" emerges in Middle High German, attested from the second half of the 12th century.[34]

The Old French term alemans is taken from the name of the Alamanni. It was loaned into Middle English as almains in the early 14th century. The word Dutch is attested in English from the 14th century, denoting continental West Germanic ("Dutch" and "German") dialects and their speakers.[35]

While in most Romance languages the Germans have been named from the Alamanni (in what became Swabia) (some, like standard Italian tedeschi, retain an older borrowing of the endonym, while the Romanian 'germani' stems from the historical correlation with the ancient region of Germania), the Old Norse, Finnish, and Estonian names for the Germans were taken from that of the Saxons. In Slavic languages, the Germans were given the name of němьci (singular němьcь), originally meaning "mute."

The English term Germans is only attested from the mid-16th century, based on the classical Latin term Germani used by Julius Caesar and later Tacitus. It gradually replaced Almain, the most common term found in Middle English and late-15th century texts, by the 18th century; the latter having already marginalised the less common medieval variants of the modern word "Dutch".[36][37][38]

History

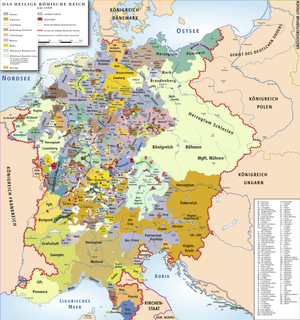

The Germans are a Germanic people, who as an ethnicity emerged during the Middle Ages. Originally part of the Holy Roman Empire, around 300 independent German states emerged during its decline after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 ending the Thirty Years War with Austria and Prussia-Brandenburg being the largest. These states, except for Austria and the Czech lands which it controlled, Switzerland and Liechtenstien, eventually formed into modern Germany in the 19th century.[39]

Origins

Although there is little substantial proof, the concept of a German ethnicity is linked to Germanic tribes of antiquity in central Europe.[40] The early Germans originated on the North German Plain as well as southern Scandinavia.[40] By the 2nd century BC, the number of Germans was significantly increasing and they began expanding into eastern Europe and southward into Celtic territory.[40] During antiquity these Germanic tribes remained separate from each other and did not have writing systems at that time.[41]

In the European Iron Age the area that is now Germany was divided into the (Celtic) La Tène horizon in Southern Germany and the (Germanic) Jastorf culture in Northern Germany. By 55 BC, the Germans had reached the Danube river and had either assimilated or otherwise driven out the Celts who had lived there, and had spread west into what is now Belgium and France.[41]

Conflict between the Germanic tribes and the forces of Rome under Julius Caesar forced major Germanic tribes to retreat to the east bank of the Rhine.[42] Roman emperor Augustus in 12 BC ordered the conquest of the Germans, but the catastrophic Roman defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest resulted in the Roman Empire abandoning its plans to completely conquer Germania.[40] Germanic peoples in Roman territory were culturally Romanized, and although much of Germania remained free of direct Roman rule, Rome deeply influenced the development of German society, especially the adoption of Christianity by the Germans who obtained it from the Romans.[42] In Roman-held territories with Germanic populations, the Germanic and Roman peoples intermarried, and Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions intermingled.[43] The adoption of Christianity would later become a major influence in the development of a common German identity.[41]

The first major public figure to speak of a German people in general, was the Roman figure Tacitus in his work Germania around 100 AD.[44] However an actual united German identity and ethnicity did not exist then, and it would take centuries of development of German culture until the concept of a German ethnicity began to become a popular identity.[45]

The Germanic peoples during the Migrations Period came into contact with other peoples; in the case of the populations settling in the territory of modern Germany, they encountered Celts to the south, and Balts and Slavs towards the east. The Limes Germanicus was breached in AD 260. Migrating Germanic tribes commingled with the local Gallo-Roman populations in what is now Swabia and Bavaria. The arrival of the Huns in Europe resulted in Hun conquest of large parts of Eastern Europe, the Huns initially were allies of the Roman Empire who fought against Germanic tribes, but later the Huns cooperated with the Germanic tribe of the Ostrogoths, and large numbers of Germans lived within the lands of the Hunnic Empire of Attila.[46] Attila had both Hunnic and Germanic families and prominent Germanic chiefs amongst his close entourage in Europe.[46] The Huns living in Germanic territories in Eastern Europe adopted an East Germanic language as their lingua franca.[47] A major part of Attila's army were Germans, during the Huns' campaign against the Roman Empire.[48] After Attila's unexpected death the Hunnic Empire collapsed with the Huns disappearing as a people in Europe–who either escaped into Asia or otherwise blended in amongst Europeans.[49]

The migration-period peoples who later coalesced into a "German" ethnicity were the Germanic tribes of the Saxons, Franci, Thuringii, Alamanni and Bavarii. These five tribes, sometimes with inclusion of the Frisians, are considered as the major groups to take part in the formation of the Germans. By the 9th century, the large tribes which lived on the territory of modern Germany had been united under the rule of the Frankish king Charlemagne, known in German as Karl der Große.[50][51][52][53] Much of what is now Eastern Germany became Slavonic-speaking (Sorbs and Veleti), after these areas were vacated by Germanic tribes (Vandals, Lombards, Burgundians, and Suebi amongst others) which had migrated into the former areas of the Roman Empire.

Medieval period

A German ethnicity emerged in the course of the Middle Ages, ultimately as a result of the formation of the Kingdom of Germany within East Francia and later the Holy Roman Empire, beginning in the 9th century. The process was gradual and lacked any clear definition, and the use of exonyms designating "the Germans" develops only during the High Middle Ages. The title of rex teutonicum "King of the Germans" is first used in the late 11th century, by the chancery of Pope Gregory VII, to describe the future Holy Roman Emperor of the German nation Henry IV.[54] Natively, the term diutscher (German) was used for the people of Germany beginning in the 12th century.

After Christianization, the Roman Catholic Church and local rulers led German expansion and settlement in areas inhabited by Slavs and Balts, known as Ostsiedlung. During the wars waged in the Baltic by the Catholic German Teutonic Knights; the lands inhabited by the ethnic group of the Old Prussians (known then simply as "Prussians"), were conquered by the Germans. The Old Prussians were an ethnic group related to the Latvian and Lithuanian Baltic peoples.[55] The former German state of Prussia took its name from the Baltic Prussians, although it was led by Germans who had assimilated the Old Prussians; the Old Prussian language was extinct by the 17th or early 18th century.[56] The Slavic people of the Teutonic-controlled Baltic were assimilated into German culture and eventually there were many intermarriages of Slavic and German families, including into Prussia's aristocracy known as the Junkers.[57] Prussian military strategist Karl von Clausewitz is a famous German whose surname is of Slavic origin.[57] Massive German settlement led to the assimilation of Baltic (Old Prussians) and Slavic (Wends) populations, who were exhausted by previous warfare.

At the same time, naval innovations led to a German domination of trade in the Baltic Sea and parts of Eastern Europe through the Hanseatic League. Along the trade routes, Hanseatic trade stations became centers of the German culture. German town law (Stadtrecht) was promoted by the presence of large, relatively wealthy German populations, their influence and political power. Thus people who would be considered "Germans", with a common culture, language, and worldview different from that of the surrounding rural peoples, colonized trading towns as far north of present-day Germany as Bergen (in Norway), Stockholm (in Sweden), and Vyborg (now in Russia). The Hanseatic League was not exclusively German in any ethnic sense: many towns who joined the league were outside the Holy Roman Empire and a number of them may only loosely be characterized as German. The Empire itself was not entirely German either. It had a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual structure, some of the smaller ethnicities and languages used at different times were Dutch, Italian, French, Czech, and Polish.[58]

By the Middle Ages, large numbers of Jews lived in the Holy Roman Empire and had assimilated into German culture, including many Jews who had previously assimilated into French culture and had spoken a mixed Judeo-French language.[59] Upon assimilating into German culture, the Jewish German peoples incorporated major parts of the German language and elements of other European languages into a mixed language known as Yiddish.[59] However tolerance and assimilation of Jews in German society suddenly ended during the Crusades with many Jews being forcefully expelled from Germany and Western Yiddish disappeared as a language in Germany over the centuries, with German Jewish people fully adopting the German language.[59]

Early Modern period

From the late 15th century, the Holy Roman Empire came to be known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. The Thirty Years' War, a series of conflicts fought mainly in the territory of modern Germany, weakened the coherence of the Holy Roman Empire, leading to the emergence of different, smaller German states known as Kleinstaaterei in 18th-century Germany.

The Napoleonic Wars were the cause of the final dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, and ultimately the cause for the quest for a German nation state in 19th-century German nationalism. After the Congress of Vienna, Austria and Prussia emerged as two competitors. Austria, trying to remain the dominant power in Central Europe, led the way in the terms of the Congress of Vienna. The Congress of Vienna was essentially conservative, assuring that little would change in Europe and preventing Germany from uniting.[60] These terms came to a sudden halt following the Revolutions of 1848 and the Crimean War in 1856, paving the way for German unification in the 1860s. By the 1820s, large numbers of Jewish German women had intermarried with Christian German men and had converted to Christianity.[61] Jewish German Eduard Lasker was a prominent German nationalist figure who promoted the unification of Germany in the mid-19th century.[62]

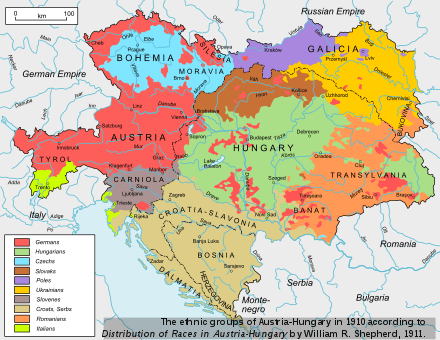

German nationalism became the sole focus of the German Question which was the question of how Germany was going to be best unified into a nation-state. The idea of unifying all German-speakers into one state was known as the Großdeutsche Lösung ("Greater German solution") which was propagated mostly by the Austrian Empire and the German Austrians. The other option, the Kleindeutsche Lösung ("Lesser German solution") only advocated unifying the northern German states without Austria and the German Austrians was supported predominantly in the Kingdom of Prussia.[63] The idea of including the Austrian Empire into a German nation-state was a problem because it included many non-German ethnic groups, as well as many of the areas it ruled had never been part of Germany and did not want to become part of a German nation-state.[64] In 1866, the feud between Austria and Prussia finally came to a head. In the final battle of the German war (Battle of Königgrätz) the Prussians successfully defeated the Austrians and succeeded in creating the North German Confederation.[65]

In 1870, after France attacked Prussia, Prussia and its new allies in Southern Germany (among them Bavaria) were victorious in the Franco-Prussian War. It created the German Empire in 1871 as a German nation-state, effectively excluding the multi-ethnic Austrian Habsburg monarchy and Liechtenstein. Integrating the Austrian Germans nevertheless remained a strong desire for many people of Germany and Austria, especially among the liberals, the social democrats and also the Catholics who were a minority within the Protestant Germany.

During the 19th century in the German territories, rapid population growth due to lower death rates, combined with poverty, spurred millions of Germans to emigrate, chiefly to the United States. Today, roughly 17% of the United States' population (23% of the white population) is of mainly German ancestry.[66][67][68]

Twentieth century

-en.png)

The dissolution of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire after World War I led to a strong desire of the population of the new Republic of German Austria to be integrated into Germany or Switzerland.[69] This was, however, prevented by the Treaty of Saint Germain and the Treaty of Versailles.[70][71] In 1930, three years before the Nazi era, there were roughly 94 million people all over the world claiming German ancestry, or about 4.5% of the world population at the time.[72][73][note 5]

During the Third Reich, the Nazis, led by Austrian-born Adolf Hitler, attempted to unite all the people they claimed were "Germans" (Volksdeutsche) under the slogan Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer ("One People, One Empire, One Leader"). This policy began in 1938 with Hitler's foreign policy Heim ins Reich ("back home to the Reich") which aimed to persuade all Germans living outside of the Reich to return "home" either as individuals or regions to a Greater Germany.[74] During the war, Heinrich Himmler who was issued with the policy of "strengthening of ethnic Germandom" created a Volksliste ("German People's List") which was used to classify all those living in the German occupied territories into different categories according to criteria by Himmler.[75] The policy of uniting all Germans included ethnic Germans in Eastern Europe,[76] many of whom had emigrated more than one hundred fifty years before and developed separate cultures in their new lands. This idea was initially welcomed by many ethnic Germans in Sudetenland,[77] Austria,[78] Poland, Danzig and western Lithuania, particularly the Germans from Klaipeda (Memel). The Swiss resisted the idea. They had viewed themselves as a distinctly separate nation since the Peace of Westphalia of 1648.

After World War II, Eastern European countries such as the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Yugoslavia expelled the ethnic Germans from their territories. Many of those had inhabited these lands for centuries, developing a unique culture. Germans were also forced to leave the former eastern territories of Germany, which were annexed by Poland (Silesia, Pomerania, parts of Brandenburg and southern part of East Prussia) and the Soviet Union (northern part of East Prussia). Between 12 and 16,5 million ethnic Germans and German citizens were expelled westwards to allied-occupied Germany.

After World War II, Austrians increasingly saw themselves as a separate nation from the German nation. In 1966, 47% people in Austria viewed themselves as Austrians. In 1990, the number increased to 79%.[79] Recent polls show that no more than 6% of the German-speaking Austrians consider themselves as "Germans".[80] An Austrian identity was vastly emphasized along with the "first-victim of Nazism theory."[81] Today over 80 percent of the Austrians see themselves as an independent nation.[82]

1945 to present

Before the collapse of communism and the reunification of Germany in 1990, Germans constituted the largest divided nation in Europe by far.[83][84][note 6] Between 1950 and 1987, about 1.4 million ethnic Germans and their dependents, mostly from Poland and Romania, arrived in Germany under special provisions of right of return. With the collapse of the Iron Curtain since 1987, 3 million "Aussiedler" – ethnic Germans, mainly from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union – took advantage of Germany's law of return to leave the "land of their birth" for Germany.[85]

Approximately 2 million, just from the territories of the former Soviet Union, have resettled in Germany since the late 1980s.[86] On the other hand, significant numbers of ethnic Germans have moved from Germany to other European countries, especially Switzerland, the Netherlands, Britain, Spain, and Portugal.

In its State of World Population 2006 report, the United Nations Population Fund lists Germany with hosting the third-highest percentage of the main international migrants worldwide, about 5% or 10 million of all 191 million migrants.[87]

Language

The native language of Germans is German, a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch, and sharing many similarities with the North Germanic and Scandinavian languages. Spoken by approximately 100 million native speakers,[88] German is one of the world's major languages and the most widely spoken first language in the European Union. German has been replaced by English as the dominant language of science-related Nobel Prize laureates during the second half of the 20th century.[89] It was a lingua franca in the Holy Roman Empire.

Dialects

- High German

- Upper German

- Bavarians (ca. 10 million) form the Austro-Bavarian linguistic group, together with those Austrians who speak German and do not live in Vorarlberg and the western Tyrol district of Reutte. Swabians (ca. 10 million) form the Alemannic group, together with the Alemannic Swiss, Liechtensteiners, Alsatians and Vorarlbergians.

- Central German dialect group (ca. 45 million)

- West Central German

- Central Franconian (Ripuarian, Kölsch), forms a dialectal unity with Luxembourgish, Rhine Franconian (Hessian)

- East Central German

- Standard German,[90] Thuringian, Upper Saxon, High Prussian, German Silesian

- West Central German

- Yiddish, a High German language of Ashkenazi Jewish origin, spoken throughout the world. It developed as a fusion of German dialects with Hebrew, Slavic languages and traces of Romance languages.[91][92]

- Upper German

- Low German (ca. 3–10 million), forms a dialectal unity with Dutch Low Saxon

- Low Saxon, East Low German

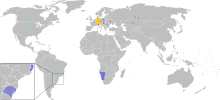

Native speakers

Global distribution of native speakers of the German language:

| Country | German-speaking population (outside German-speaking countries) |

|---|---|

| 5,000,000[93] | |

| 3,000,000[93] | |

| 2,000,000[93] | |

| 500,000[93] | |

| 450,000[93] – 620,000[94] | |

| 250,000[93] | |

| 220,000[93] | |

| 148,000[95] | |

| 110,000[93] | |

| 100,000 (Mennonites)[96] | |

| 75,000 (German expatriate citizens)[93] | |

| 66,000[93] | |

| 56,000[97] | |

| 40,000[93] | |

| 36,000[93] | |

| 35,000[98] | |

| 30,000 (German expatriate citizens)[93] | |

| 20,000[93] | |

| 15,000[93] | |

| 10,000[93] | |

| 4,206[99] | |

Geographic distribution

People of German origin are found in various places around the globe. United States is home to approximately 50 million German Americans or one third of the German diaspora, making it the largest centre of German-descended people outside Germany. Brazil is the second largest with 5 million people claiming German ancestry. Other significant centres are Canada, Argentina, South Africa and France each accounting for at least 1 million. While the exact number of German-descended people is difficult to calculate, the available data makes it safe to claim the number is exceeding 100 million people.[1]

Culture

Literature

German literature can be traced back to the Middle Ages, with the most notable authors of the period being Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach. The Nibelungenlied, whose author remains unknown, is also an important work of the epoch, as is the Thidrekssaga. The fairy tales collections collected and published by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in the 19th century became famous throughout the world.

Theologian Luther, who translated the Bible into German, is widely credited for having set the basis for the modern "High German" language. Among the most admired German poets and authors are Lessing, Goethe, Schiller, Kleist, Hoffmann, Brecht, Heine and Schmidt. Nine Germans have won the Nobel Prize in literature: Theodor Mommsen, Paul von Heyse, Gerhart Hauptmann, Thomas Mann, Nelly Sachs, Hermann Hesse, Heinrich Böll, Günter Grass, and Herta Müller.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing of the Enlightenment.

Gerhart Hauptmann, a German dramatist and novelist who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1912.

Gerhart Hauptmann, a German dramatist and novelist who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1912. Thomas Mann, a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate.

Thomas Mann, a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. Günter Grass was a recipient of the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Günter Grass was a recipient of the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature.- Herta Müller, of Banat Swabian origin, was born into a German minority in Romania. She is the recipient of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature for her novel Atemschaukel.

Philosophy

Germany's influence on philosophy is historically significant and many notable German philosophers have helped shape Western philosophy since the Middle Ages. The rise of the modern natural sciences and the related decline of religion raised a series of questions, which recur throughout German philosophy, concerning the relationships between knowledge and faith, reason and emotion, and scientific, ethical, and artistic ways of seeing the world.

.jpg)

German philosophers have helped shape western philosophy from as early as the Middle Ages (Albertus Magnus). Later, Leibniz (17th century) and most importantly Kant played central roles in the history of philosophy. Kantianism inspired the work of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche as well as German idealism defended by Fichte and Hegel. Engels helped develop communist theory in the second half of the 19th century while Heidegger and Gadamer pursued the tradition of German philosophy in the 20th century. A number of German intellectuals were also influential in sociology, most notably Adorno, Habermas, Horkheimer, Luhmann, Simmel, Tönnies, and Weber. The University of Berlin founded in 1810 by linguist and philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt served as an influential model for a number of modern western universities.

In the 21st century, Germany has been an important country for the development of contemporary analytic philosophy in continental Europe, along with France, Austria, Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries.[100]

A statue of Albertus Magnus, a medieval German philosopher, now declared a Catholic saint.

A statue of Albertus Magnus, a medieval German philosopher, now declared a Catholic saint. Arthur Schopenhauer, a German philosopher best known for his book, The World as Will and Representation. He has influenced many other thinkers through his work.

Arthur Schopenhauer, a German philosopher best known for his book, The World as Will and Representation. He has influenced many other thinkers through his work. Karl Marx's ideas played a significant role in the establishment of the social sciences and the development of the socialist movement. He published numerous books during his lifetime, the most notable being The Communist Manifesto and Capital. He is also considered one of the greatest economists of all time.

Karl Marx's ideas played a significant role in the establishment of the social sciences and the development of the socialist movement. He published numerous books during his lifetime, the most notable being The Communist Manifesto and Capital. He is also considered one of the greatest economists of all time. Friedrich Engels was a social scientist, author, political theorist, philosopher, and father of Marxist theory, alongside Karl Marx. He is the co-author of The Communist Manifesto.

Friedrich Engels was a social scientist, author, political theorist, philosopher, and father of Marxist theory, alongside Karl Marx. He is the co-author of The Communist Manifesto. Max Weber was a sociologist, philosopher, and political economist who profoundly influenced social theory, social research, and the discipline of sociology itself. Weber is often cited, with Émile Durkheim and Karl Marx, as one of the three founding architects of sociology.

Max Weber was a sociologist, philosopher, and political economist who profoundly influenced social theory, social research, and the discipline of sociology itself. Weber is often cited, with Émile Durkheim and Karl Marx, as one of the three founding architects of sociology.

Science

Germany has been the home of many famous inventors and engineers, such as Johannes Gutenberg, who is credited with the invention of movable type printing in Europe; Hans Geiger, the creator of the Geiger counter; and Konrad Zuse, who built the first electronic computer.[101] German inventors, engineers and industrialists such as Zeppelin, Daimler, Diesel, Otto, Wankel, Von Braun and Benz helped shape modern automotive and air transportation technology including the beginnings of space travel.[102][103]

The work of David Hilbert, Max Planck and Albert Einstein was crucial to the foundation of modern physics, which Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger developed further.[104] They were preceded by such key physicists as Hermann von Helmholtz and Joseph von Fraunhofer, among others. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays, an accomplishment that made him the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901.[105] The Walhalla temple for "laudable and distinguished Germans", features a number of scientists, and is located east of Regensburg, in Bavaria.[106][107]

A statue commemorating Johannes Gutenberg for his invention of the first movable type; printing press.

A statue commemorating Johannes Gutenberg for his invention of the first movable type; printing press..jpg) The magnificent panorama of the metal interlinking in the bowels of the world's first computer created by Konrad Zuse.

The magnificent panorama of the metal interlinking in the bowels of the world's first computer created by Konrad Zuse. The Geiger counter, invented by Hans Geiger, is a type of particle detector that measures ionizing radiation.

The Geiger counter, invented by Hans Geiger, is a type of particle detector that measures ionizing radiation. A print of one of the first X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen (1845–1923) of the left hand of his wife Anna Bertha Ludwig. It was presented to Professor Ludwig Zehnder of the Physik Institut, University of Freiburg, on 1 January 1896.

A print of one of the first X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen (1845–1923) of the left hand of his wife Anna Bertha Ludwig. It was presented to Professor Ludwig Zehnder of the Physik Institut, University of Freiburg, on 1 January 1896.

Music

In the field of music, Germany claims some of the most renowned classical composers of the world including Bach, Mozart and Beethoven, who marked the transition between the Classical and Romantic eras in Western classical music. Other composers of the Austro-German tradition who achieved international fame include Brahms, Wagner, Haydn, Schubert, Händel, Schumann, Liszt, Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Johann Strauss II, Bruckner, Mahler, Telemann, Richard Strauss, Schoenberg, Orff, and most recently, Henze, Lachenmann, and Stockhausen.

As of 2008, Germany is the fourth largest music market in the world[108] and has exerted a strong influence on Dance and Rock music, and pioneered trance music. Artists such as Herbert Grönemeyer, Scorpions, Rammstein, Nena, Dieter Bohlen, Tokio Hotel and Modern Talking have enjoyed international fame. German musicians and, particularly, the pioneering bands Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk have also contributed to the development of electronic music.[109] Germany hosts many large rock music festivals annually. The Rock am Ring festival is the largest music festival in Germany, and among the largest in the world. German artists also make up a large percentage of Industrial music acts, which is called Neue Deutsche Härte. Germany hosts some of the largest Goth scenes and festivals in the entire world, with events like Wave-Gothic-Treffen and M'era Luna Festival easily attracting up to 30,000 people. Amongst Germany's famous artists there are various Dutch entertainers, such as Johannes Heesters.[110]

Richard Strauss is considered a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras.

Richard Strauss is considered a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. Richard Wagner greatly influenced the development of classical music; his Tristan und Isolde is sometimes described as marking the start of modern music.

Richard Wagner greatly influenced the development of classical music; his Tristan und Isolde is sometimes described as marking the start of modern music. Scorpions, a rock band formed in 1965, now viewed as one of the best-selling acts in music history.

Scorpions, a rock band formed in 1965, now viewed as one of the best-selling acts in music history. Nena, a singer and actress, who brought Neue Deutsche Welle to international attention with her song 99 Luftballons.

Nena, a singer and actress, who brought Neue Deutsche Welle to international attention with her song 99 Luftballons. Modern Talking, a synthpop duo consisting of Thomas Anders and Dieter Bohlen, became one of the most successful German acts in the 1980s.

Modern Talking, a synthpop duo consisting of Thomas Anders and Dieter Bohlen, became one of the most successful German acts in the 1980s.

Cinema

German cinema dates back to the very early years of the medium with the work of Max Skladanowsky. It was particularly influential during the years of the Weimar Republic with German expressionists such as Robert Wiene and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. The Nazi era produced mostly propaganda films although the work of Leni Riefenstahl still introduced new aesthetics in film. From the 1960s, New German Cinema directors such as Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder placed West-German cinema back onto the international stage with their often provocative films, while the DEFA film studio controlled film production in the GDR.

More recently, films such as Das Boot (1981), The Never Ending Story (1984) Run Lola Run (1998), Das Experiment (2001), Good Bye Lenin! (2003), Gegen die Wand (Head-on) (2004) and Der Untergang (Downfall) (2004) have enjoyed international success. In 2002 the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film went to Caroline Link's Nowhere in Africa, and in 2007 to Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's The Lives of Others. The Berlin International Film Festival, held yearly since 1951, is one of the world's foremost film and cinema festivals.[111]

A sign advertising the Berlin International Film Festival

A sign advertising the Berlin International Film Festival Leni Riefenstahl was widely noted for her aesthetics and innovations as a filmmaker

Leni Riefenstahl was widely noted for her aesthetics and innovations as a filmmaker A poster for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari directed by Robert Wiene

A poster for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari directed by Robert Wiene

Architecture

.jpg)

Architectural contributions from Germany include the Carolingian and Ottonian styles, important precursors of Romanesque. The region then produced significant works in styles such as the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque.

The nation was particularly important in the early modern movement through the Deutscher Werkbund and the Bauhaus movement identified with Walter Gropius. The Nazis closed these movements and favoured a type of neo-classicism. Since World War II, further important modern and post-modern structures have been built, particularly since the reunification of Berlin.

Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus, the former Reichsluftfahrtministerium (now a Federal Ministry of Finance building)

Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus, the former Reichsluftfahrtministerium (now a Federal Ministry of Finance building)- The market place at Dornstetten

Religion

Roman Catholicism was the sole established religion in the Holy Roman Empire until the Reformation changed this drastically. In 1517, Martin Luther challenged the Catholic Church as he saw it as a corruption of Christian faith. Through this, he altered the course of European and world history and established Protestantism.[112] The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history. The war was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most of the countries of Europe. The war was fought largely as a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire.[113]

According to the latest nationwide census, Roman Catholics constituted 29.5% of the total population of Germany, followed by the Evangelical Protestants at 27.9%. Other Christian denominations, other religions, atheists or not specified constituted 42.6% of the population at the time. Among "others" are Protestants not included in Evangelical Church of Germany, and other Christians such as the Restorationist New Apostolic Church. Protestantism was more common among the citizens of Germany.[114] The North and East Germany is predominantly Protestant, the South and West rather Catholic. Nowadays there is a non-religious majority in Hamburg and the East German states.[115]

Historically, Germany had a substantial Jewish minority. Only a few thousand people of Jewish origin remained in Germany after the Holocaust, but the German Jewish community now has approximately 100,000 members, many from the former Soviet Union. Germany also has a substantial Muslim minority, most of whom are immigrants from Turkey.

German theologians include Luther, Melanchthon, Schleiermacher, Feuerbach, and Rudolf Otto. Also Germany brought up many mystics including Meister Eckhart, Rudolf Steiner, Jakob Boehme, and some popes (e.g. Benedict XVI).

The Meister Eckhart portal of the Erfurt Church

The Meister Eckhart portal of the Erfurt Church_and-or_Workshop_-_Portrait_of_Philip_Melanchton.jpg)

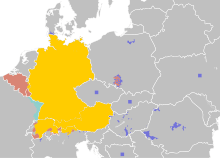

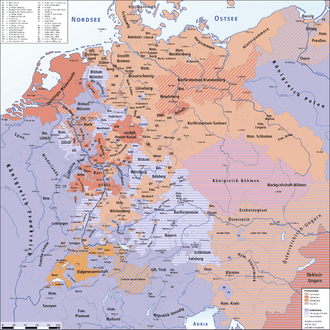

Religion in the Holy Roman Empire on the eve of the Thirty Years' War

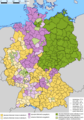

Religion in the Holy Roman Empire on the eve of the Thirty Years' War Predominant religious group according to 2011 nationwide census. Catholics are dominant in the south and west, the Non-religious (incl. other religions and not specified) dominate in the east and the large cities, Protestants dominate in north and central parts of Germany

Predominant religious group according to 2011 nationwide census. Catholics are dominant in the south and west, the Non-religious (incl. other religions and not specified) dominate in the east and the large cities, Protestants dominate in north and central parts of Germany

Sport

Sport forms an integral part of German life, as demonstrated by the fact that 27 million Germans are members of a sports club and an additional twelve million pursue such an activity individually.[116] Football is by far the most popular sport, and the German Football Federation (Deutscher Fußballbund) with more than 6.3 million members is the largest athletic organisation in the country.[116] It also attracts the greatest audience, with hundreds of thousands of spectators attending Bundesliga matches and millions more watching on television.

Other popular sports include handball, volleyball, basketball, ice hockey, and Winter sports.[116] Historically, German sportsmen have been successful contenders in the Olympic Games, ranking third in an all-time Olympic Games medal count, combining East and West German medals. In the 2012 Summer Olympics, Germany finished sixth overall, whereas in the 2010 Winter Olympics Germany finished second.

There are also many Germans in the American NBA. In 2011, Dirk Nowitzki won his first NBA Championship with the Dallas Mavericks by upsetting the Miami Heat. He was also named that year's NBA Finals Most Valuable Player.

- Berlin Marathon

Michael Schumacher has claimed 91 race victories and 7 championships in his F1 career.

Michael Schumacher has claimed 91 race victories and 7 championships in his F1 career..jpg) German national football team in 2011

German national football team in 2011 Dirk Nowitzki (in green), Dallas Mavericks power forward, 2011 NBA Champion and Finals MVP

Dirk Nowitzki (in green), Dallas Mavericks power forward, 2011 NBA Champion and Finals MVP

Society

Germany is a modern, advanced society, shaped by a plurality of lifestyles and regional identities.[117] The country has established a high level of gender equality, promotes disability rights, and is legally and socially tolerant towards homosexuals. Gays and lesbians can legally adopt their partner's biological children, and civil unions have been permitted since 2001.[118] Former Foreign minister Guido Westerwelle and the former mayor of Berlin, Klaus Wowereit, are openly gay.[119]

During the last decade of the 20th century, Germany changed its attitude towards immigrants. Until the mid-1990s the opinion was widespread that Germany is not a country of immigration, even though about 20% of the population were of non-German origin. Today the government and a majority of the German society are acknowledging that immigrants from diverse ethnocultural backgrounds are part of the German society and that controlled immigration should be initiated based on qualification standards.[120]

Since the 2006 FIFA World Cup, the internal and external evaluation of Germany's national image has changed.[121] In the annual Nation Brands Index global survey, Germany became significantly and repeatedly more highly ranked after the tournament. People in 20 different states assessed the country's reputation in terms of culture, politics, exports, its people and its attractiveness to tourists, immigrants and investments. Germany has been named the world's second most valued nation among 50 countries in 2010.[122] Another global opinion poll, for the BBC, revealed that Germany is recognised for the most positive influence in the world in 2010. A majority of 59% have a positive view of the country, while 14% have a negative view.[123][124]

With an expenditure of €67 billion on international travel in 2008, Germans spent more money on travel than any other country. The most visited destinations were Spain, Italy and Austria.[125]

- German females in the German tracht national costumes of the time of Biedermeier

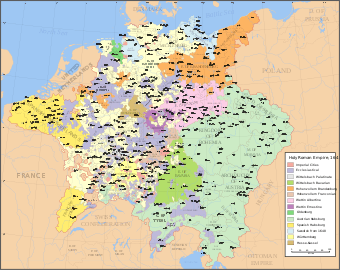

A map of Holy Roman Empire in 1400, reflecting the German society's regional diversity

A map of Holy Roman Empire in 1400, reflecting the German society's regional diversity Boundary sign of Caseritz / Kozarcy in German and Upper Sorbian language

Boundary sign of Caseritz / Kozarcy in German and Upper Sorbian language Rutenfest in Ravensburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, celebrating the folklore story of "The Seven Swabians" by the Brothers Grimm

Rutenfest in Ravensburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, celebrating the folklore story of "The Seven Swabians" by the Brothers Grimm Actors from Germany in film "Als der Tod ins Leben wuchs" of Sebastian Ed Erhenberg as Volga Germans

Actors from Germany in film "Als der Tod ins Leben wuchs" of Sebastian Ed Erhenberg as Volga Germans

Identity

.jpg)

The event of the Protestant Reformation and the politics that ensued has been cited as the origins of German identity that arose in response to the spread of a common German language and literature.[45] Early German national culture was developed through literary and religious figures including Martin Luther, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller.[126] The concept of a German nation was developed by German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder.[127] The popularity of German identity arose in the aftermath of the French Revolution.[44]

Persons who speak German as their first language, look German and whose families have lived in Germany for generations are considered "most German", followed by categories of diminishing Germanness such as Aussiedler (people of German ancestry whose families have lived in Eastern Europe but who have returned to Germany), Restdeutsche (people living in lands that have historically belonged to Germany but which is currently outside of Germany), Auswanderer (people whose families have emigrated from Germany and who still speak German), German speakers in German-speaking nations such as Austrians, and finally people of German emigrant background who no longer speak German.[128]

Pan-Germanism's origins began in the early 19th century following the Napoleonic Wars. The wars launched a new movement that was born in France itself during the French Revolution. Nationalism during the 19th century threatened the old aristocratic regimes. Many ethnic groups of Central and Eastern Europe had been divided for centuries, ruled over by the old Monarchies of the Romanovs and the Habsburgs. Germans, for the most part, had been a loose and disunited people since the Reformation when the Holy Roman Empire was shattered into a patchwork of states. The new German nationalists, mostly young reformers such as Johann Tillmann of East Prussia, sought to unite all the German-speaking and ethnic-German (Volksdeutsche) people.

1871–1918

By the 1860s the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire were the two most powerful nations dominated by German-speaking elites. Both sought to expand their influence and territory. The Austrian Empire – like the Holy Roman Empire – was a multi-ethnic state, but German-speaking people there did not have an absolute numerical majority; the creation of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was one result of the growing nationalism of other ethnicities especially the Hungarians in Austrian territory. Prussia under Otto von Bismarck would eventually ride on the coat-tails of nationalism to unite all of modern-day Germany. Following several wars, most notably the German war in 1866 between the two most powerful German states, Austria and Prussia, with the latter being victorious, the German Empire ("Second Reich") was created in 1871 as "Little Germany" without Austria following the proclamation of Wilhelm I as head of a union of German-speaking states, while disregarding millions of its non-German subjects who desired self-determination from German rule.

The creation of the multi-ethnic Austria-Hungary empire created strong ethnic conflict between the different ethnicities of the empire. German nationalism in Austria grew among all social circles of the empire, many wanted to be unified with the German Reich to form a Greater Germany and wanted policies to be carried out to enforce their German ethnic identity rejecting any Austrian pan-ethnic identity.[129] Many German Austrians felt annoyed that they were excluded from the German Empire since it included various non-German ethnic groups.[130] Prominent Austrian pan-Germans such as Georg Ritter von Schönerer created pan-German movements which demanded the annexation of all ethnic German territories. Members of such movements often wore blue cornflowers, known to be the favourite flower of German Emperor William I, in their buttonholes, along with cockades in the German national colours (black, red, and yellow).[131] Both symbols were temporarily banned in Austrian schools.[132] Populists such as the Viennese major Karl Lueger used anti-semitism and pan-Germanism for their own political purposes.[133] Despite Bismarck's victory over Austria in 1866 which ultimately excluded Austria and the German Austrians from the Reich, many Austrian pan-Germans idolized him.[134]

There was also a rejection of Roman Catholicism with the Away from Rome! movement calling for German speakers to identify with Lutheran or Old Catholic churches.[135]

1918–1945

Following the defeat in World War I, influence of German-speaking elites over Central and Eastern Europe was greatly limited. At the Treaty of Versailles Germany was substantially reduced in size. Austria-Hungary was split up. The former German-speaking areas of Austria-Hungary was reduced to a rump state called the "Republic of German-Austria" (German: Deutschösterreich). On 12 November, the National Assembly declared the rump state a republic and Social Democrat Karl Renner as provisional chancellor. On the same day, it drafted a provisional constitution which stated that "German-Austria is a democratic republic" (Article 1) and "German-Austria is an integral part of the German reich" (Article 2) with the hope of joining Germany.[136] The name "German-Austria" and union with Germany were forbidden by the Treaty of Saint-Germain and the Treaty of Versailles.[137][138] German-Austria lost the territories of the Sudetenland and German Bohemia to Czechoslovakia, South Tyrol to Italy, and southern Carinthia and Styria to Yugoslavia and the rump state was renamed "Republic of Austria". With these changes, the era of the First Austrian Republic began.[139] These events are sometimes considered to be a pre-Anschluss attempt.

During the 1920s, the constitutions of both the First Austrian Republic and the Weimar Republic included the goal of union between the two countries which was supported by all different political parties. In the early 1930s, before the Nazis seized power, popularity for union between Austria and Germany remained strong and the Austrian government looked at the possibility of a customs union with Germany in 1931 but this was stopped by French opposition.[140] In 1933, after Austrian-born Hitler came to power, support for an Anschluss grew. The Austrofascism era of Dollfuss/Schuschnigg between 1934-1938 accepted that Austrians were Germans and that Austria was a "German state" but was strongly opposed to Hitler's desire to annex Austria to the Third Reich and wished for Austria to remain independent.[141]

The Heim ins Reich initiative (German: literally Home into the Reich, meaning Back to Reich, see Reich) was a policy pursued by Nazi Germany which attempted to convince people of German descent living outside of Germany (such as Sudetenland) that they should strive to bring these regions "home" into a greater Germany, but also relocate from territories that were not under German control, following the conquest of Poland in accordance with the Nazi-Soviet pact. This policy began in 1938 on 12 March when Hitler annexed Austria to the Third Reich.

Volga Germans living in the Soviet Union were interned in gulags or forcibly relocated during the Second World War.[142]

1945–1990

World War II brought about the decline of Pan-Germanism, much as World War I had led to the demise of Pan-Slavism. The Germans in Central and Eastern Europe fled[143] and were expelled,[144] parts of Germany itself were devastated, and the country was divided, firstly into Russian, French, American, and British zones and then into West Germany and East Germany.

Germany suffered even larger territorial losses than it did in the First World War, with huge portions of eastern Germany directly annexed by the Soviet Union[145] and Poland.[146][147] The scale of the Germans' defeat was unprecedented. Nationalism and Pan-Germanism became almost taboo because they had been used so destructively by the Nazis. Indeed, the word "Volksdeutscher" in reference to ethnic Germans naturalized during WWII later developed into a mild epithet.

From the 1960s, Germany also saw increasing immigration, especially from Turkey, under an official programme aimed at encouraging "Gastarbeiter" or guestworkers to the country to provide labour during the post-war economic boom years. Although it had been expected that such workers would return home, many settled in Germany, with their descendants becoming German citizens.[148]

1990–present

However, German reunification in 1990 revived the old debates. The fear of nationalistic misuse of Pan-Germanism nevertheless remains strong. But the overwhelming majority of Germans today are not chauvinistic in nationalism, but in 2006 and again in 2010, the German National Football Team won third place in the 2006 and 2010 FIFA World Cups, ignited a positive scene of German pride, enhanced by success in sport.

For decades after the Second World War, any national symbol or expression was a taboo.[149] However, the Germans are becoming increasingly patriotic.[149][150] During a study in 2009, in which some 2,000 German citizens age 14 and upwards filled out a questionnaire, nearly 60% of those surveyed agreed with the sentiment "I'm proud to be German." And 78%, if free to choose their nation, would opt for German nationality with "near or absolute certainty".[151] Another study in 2009, carried out by the Identity Foundation in Düsseldorf, showed that 73% of the Germans were proud of their country, twice more than 8 years earlier. According to Eugen Buss, a sociology professor at the University of Hohenheim, there's an ongoing normalisation and more and more Germans are becoming openly proud of their country.[150]

.jpg)

In the midst of the European sovereign-debt crisis, Radek Sikorski, Poland's Foreign Minister, stated in November 2011, "I will probably be the first Polish foreign minister in history to say so, but here it is: I fear German power less than I am beginning to fear German inactivity. You have become Europe's indispensable nation."[152] According to Jacob Heilbrunn, a senior editor at The National Interest, such a statement is unprecedented when taking into consideration Germany's history. "This was an extraordinary statement from a top official of a nation that was ravaged by Germany during World War II. And it reflects a profound shift taking place throughout Germany and Europe about Berlin's position at the center of the Continent."[152] Heilbrunn believes that the adage, "what was good for Germany was bad for the European Union" has been supplanted by a new mentality—what is in the interest of Germany is also in the interest of its neighbors. The evolution in Germany's national identity stems from focusing less on its Nazi past and more on its Prussian history, which many Germans believe was betrayed—and not represented—by Nazism.[152] The evolution is further precipitated by Germany's conspicuous position as Europe's strongest economy. Indeed, this German sphere of influence has been welcomed by the countries that border it, as demonstrated by Polish foreign minister Radek Sikorski's effusive praise for his country's western neighbor.[152] This shift in thinking is boosted by a newer generation of Germans who see World War II as a distant memory.

See also

- Demographics of Germany

- Anti-German sentiment

- Die Deutschen, ZDF's documentary television series

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Genetic history of Europe

- German eastward expansion

- List of Alsatians and Lorrainians

- List of Austrians

- List of ancient Germanic peoples

- List of Swiss people

- List of terms used for Germans

- Names for the German language

- Organised persecution of ethnic Germans

Notes

- Above all Lutheranism, Calvinism, and United Protestant (Lutheran & Reformed); further details: Prussian Union of churches

- Above all Lutheranism, Calvinism, and United Protestant (Lutheran & Reformed); further details: Evangelical Church in Germany

- alongside the slightly earlier term Almayns; John of Trevisa's 1387 translation of Ranulf Higdon's Polychronicon has: Þe empere passede from þe Grees to þe Frenschemen and to þe Germans, þat beeþ Almayns. During the 15th and 16th centuries, Dutch was the adjective used in the sense "pertaining to Germans". Use of German as an adjective dates to ca. 1550. The adjective Dutch narrowed its sense to "of the Netherlands" during the 17th century.

- In these countries, the number of people claiming German ancestry exceeds 1,000,000 and a significant percentage of the population claim German ancestry. For sources: see table in German diaspora main article.

- Here is used the estimate of the United Nations (2,07 billion people in the world, 1930), and all the populations from the map combined. 2,07 billion is taken as 100%, and 93,379,200 is taken as x. 2,700,000,000 - 100%, 93,379,200 - x. x=93,379,200*100%/2,070,000,000=4,5110724637681=4,5%

- Divided refers to relatively strong regionalism among the Germans within the Federal Republic of Germany. The events of the 20th century also affected the nation. As a result, the German people remain divided in the 21st century, though the degree of division is one much diminished after two world wars, the Cold War, and the German reunification.

References

- "Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia" by Jeffrey Cole (2011), p. 171; "Estimates of the total number of Germans in the world range from 100 million to 150 million, depending on how German is defined, ..."

- "Population". 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Ich bin ein brasileiro: Finding a little piece of Germany in Brazil - Al Jazeera America". 26 February 2016. Archived from the original on 26 February 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "The German Times Online - German Roots - Gisele Bundchen". 2 April 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Argentina Population 2017". World Population Review. 20 December 2017.

Argentina has an estimated 2017 population of 44.27 million ... about 8% are descended from German immigrants

- http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/imm/Table.cfm?Lang=E&T=31&Geo=01

- "Alemanes en Chile: entre el pasado colono y el presente empresarial" (in Spanish). Deutsche Welle. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

Spanish: Hoy, el perfil de los alemanes residentes aquí es distinto y ya no tienen el peso numérico que alguna vez alcanzaron. En los años 40 y 50 eran en Chile el segundo mayor grupo de extranjeros, representando el 13% (13.000 alemanes). Según el último censo de 2002, en cambio, están en el octavo lugar: son sólo 5.500 personas, lo que equivale al 5% de los foráneos. Sin embargo, la colonia formada por familias de origen alemán es activa y numerosa. Según explica Karla Berndt, gerente de comunicaciones de la Cámara Chileno-Alemana de Comercio (Camchal), los descendientes suman 500.000. Concentrados en el sur y centro del país, donde encuentran un clima más afín, su red de instituciones es amplia. 'Hay clínicas, clubes, una Liga Chileno-Alemana, compañías de bomberos y un periódico semanal en alemán llamado Cóndor. Chile es el lugar en el que se concentra el mayor número de colegios alemanes, 24, lo que es mucho para un país tan chico de sólo 16 millones de habitantes', relata Berndt.

English: Today, the profile of the Germans living here is different and no longer have the numerical weight they once reached. In the 1940s and 1950s they were in Chile's second largest foreign group, accounting for 13% (13,000 Germans). According to the last census in 2002, however, they are in eighth place: they are only 5,500 people, equivalent to 3% of foreigners. However, the colony of families of German origin is active and numerous. According to Karla Berndt, communications manager for the German-Chilean Chamber of Commerce (Camchal), descendants totaled 500,000. Concentrated in the south and center of the country, where they find a more congenial climate, its network of institutions is wide. 'There are clinics, clubs, a Chilean-German League, fire companies and a German weekly newspaper called Condor. Chile is the place in which the largest number of German schools, 24 which is a lot for such a small country of only 16 million people', says Berndt. - "Une estimation des populations d'origine étrangère en France en 2011".

Immigrés : 78 000 ; 1ère génération née en France : 129 000 ; 2ème génération née en France : 230 000 ; Total : 437 000

- "CBS StatLine - Population; sex, age, origin and generation, 1 January". Statline.cbs.nl. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Country: Italy". Joshua Project. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Bevölkerung zu Jahresbeginn seit 2002 nach detaillierter Staatsangehörigkeit" [Population at the beginning of the year since 2002 by detailed nationality] (PDF). Statistics Austria (in German). 14 June 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- "Country: Kazakhstan". Joshua Project. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 - 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus - 12. Ethnic data] (PDF). Hungarian Central Statistical Office (in Hungarian). Budapest. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- "Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011" (PDF). Stat.gov.pl. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?path=/t20/e245/p08/l0/&file=01006.px&L=0

- Kopp, Horst (20 December 2017). Area Studies, Business and Culture: Results of the Bavarian Research Network Forarea. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783825866235. Retrieved 20 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- Amt, Auswärtiges. "Federal Foreign Office - Uruguay". Auswärtiges Amt DE. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Rumänien: Ethnischer Deutscher erhält Spitzenamt in Regierungspartei". Spiegel.de. 23 February 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2017 – via Spiegel Online.

- "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 | English version | Results | Nationality and citizenship | The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue". 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 16 January 2020. no-break space character in

|title=at position 38 (help) - Personer med innvandringsbakgrunn, etter innvandringskategori, landbakgrunn og kjønn SSB, retrieved 13 July 2015

- "Fakta om Norge". Utlandsjobb.nu. Utlandsjobb.nu. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

90 000 svenskar bor i Norge

- "Federal Foreign OfficeDominican Republic". 20 October 2006. Archived from the original on 20 October 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "População Estrangeira Residente em Portugal - Alemanha" (PDF). Ministério da Economia. 20 June 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- "Germany - The Lutheran World Federation". Lutheranworld.org. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Danver, Steven L. (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 313. ISBN 978-1317464006.

Germans are a Germanic (or Teutonic) people that are indigenous to Central Europe

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 769. ISBN 0-313-30984-1. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz (2003). The Making of a Language. Walter de Gruyter. p. 449. ISBN 311017099X. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

The Germanic [peoples] still include: Englishmen, Dutchmen, Germans, Danes, Swedes, Saxons. Therefore, [in the same way] as Poles, Russians, Czechs, Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians belong to the Slavic [peoples]...

- van der Sijs, Nicoline (2003). Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages. Amsterdam University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9089641246. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

Dutch quite often refers to German (because of the similarity in sound between Dutch and Deutsch) and sometimes even Scandinavians and other Germanic people.

- "Germany". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- "German 'should be a working language of EU', says Merkel's party". Telegraph.co.uk. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Cole, Jeffrey (2011). Ethnic Groups of Europe. ISBN 9781598843026. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- e.g. Walther von der Vogelweide. See Lexer, Mittelhochdeutsches Handwörterbuch (1872–1878), s.v. "Diutsche". The Middle High German Song of Roland (ca. 1170) has in diutisker erde (65.6) for "in the German realm, in Germany". The phrase in tütschem land, whence the modern Deutschland, is attested in the late 15th century (e.g. Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg, Ship of Fools, see Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch, s.v. "Deutsch").

- OED, s.v. "Dutch, adj., n., and adv."

- Schulze, Hagen (1998). Germany: A New History. Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-674-80688-3.

- "German", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Ed. T. F. Hoad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- W. Ridgeway:The Origin and Influence of the Thoroughbred Horse. Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 22.

- See:

- Ozment, Steven (2005), A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People, Harper Collins, pp. 120–121, 161, 212, ISBN 0-06-093483-2

- Segarra, Eda (1977), A Social History of Germany, 1648–1914, Taylor & Francis, pp. 5, 15, 183, ISBN 0-416-77620-5

- Whaley, Joachim (2011), Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume II: The Peace of Westphalia to the Dissolution of the Reich, 1648–1806, Oxford History of Early Modern Europe, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-969307-8

- World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish, 2009. Pp. 311.

- Yehuda Cohen. The Germans: Absent Nationality and the Holocaust. SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS, 2010. Pp. 27.

- World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish, 2009. Pp. 311–312.

- Marvin Perry, Myrna Chase, Margaret Jacob, James R. Jacob, Theodore H. Von Laue. Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society, Volume I: To 1789. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2009. Pp. 212.

- Jeffrey E. Cole. Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2011. Pp. 172.

- Motyl 2001, pp. 189.

- A History of the Ostrogoths. Pp. 46.

- Sinor, Denis. 1990. The Hun period. In D. Sinor, ed., The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–205.

- Jane Penrose. Rome and Her Enemies: An Empire Created and Destroyed by War The Germans and the Romans. Cambridge, England, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2008. Pp. 288.

- Brian A. Pavlac. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities Throughout History. Rowman & Littlefield, 2010. Pp. 102.

- "HISTORY OF CHARLEMAGNE". Historyworld.net. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "How Charlemagne Changed the World". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg, Germany (26 November 2012). "Wie Karl der Große Aachen zur kaiserlichen Metropole ausbaute". SPIEGEL ONLINE. Retrieved 7 January 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Schwanitz, Dietrich (2002). Bildung. Alles was man wissen muß (in German). München: Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag. ISBN 3-442-15147-3.

- Schulze, Hagen (2001). Germany. p. 18. ISBN 9780674005457. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier. Soziolinguistik: Ein Internationales Handbuch Zur Wissenschaft Von Sprache und Gesellschaft. English translation edition. Walter de Gruyter, 2006. Pp. 1866.

- Encyclopædia Britannica entry 'Old Prussian language'

- G. J. Meyer. A World Undone: The Story of the Great War 1914 to 1918. Random House Digital, Inc., 2007. Pp. 179.

- "Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation". Dhm.de. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier. Soziolinguistik: Ein Internationales Handbuch Zur Wissenschaft Von Sprache und Gesellschaft. English translation edition. Walter de Gruyter, 2006. Pp. 1925.

- "Raffael Scheck's Web Page » Raffael Scheck's Home Page". Colby.edu. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Deborah Sadie Hertz. How Jews Became Germans: The History of Conversion and Assimilation in Berlin. Yale University, 2007. Pp. 193.

- James F. Harris. A Study in the Theory and Practice of German Liberalism: Eduard Lasker, 1829–1884. University Press of America, 1984. Pp. 17.

- Dirk Verheyen (30 July 1999). The German Question: A Cultural, Historical, and Geopolitical Exploration. Avalon Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8133-6878-8.

- Imanuel Geiss (16 December 2013). The Question of German Unification: 1806-1996. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-136-18568-7.

- "Austria-Hungary Prussia War 1866". Onwar.com. 16 December 2000. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- "American FactFinder - Search". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Regular Session 2009-2010 Senate Resolution 141 P.N. 1216". Legis.state.pa.us. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Ihre Meinung. "Als Vorarlberg Schweizer Kanton werden wollte – Vorarlberg – Aktuelle Nachrichten – Vorarlberg Online". Vol.at. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Austria votes to merge with Germany in a referendum". Famousdaily.com. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Annexation of Austria - Analysis of the Inter-War Period". Socialexperts.weebly.com. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Data from United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. "The World at Six Billion," 1999. Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Deutsche auf der Erde" (1930), map

- Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web. (2011) Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, p. 194

- Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia, pp. 543-4

- "The Nazi Concept of 'Volksdeutsche' and the Exacerbation of Anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe, 1939–45". DeepDyve. 1 January 1994. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- "Sudeten Germans continue fight for right of return". Haaretz.com. 3 September 2003. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Willian L. Shirer (1984). Twentieth Century Journey, Volume 2, The Nightmare Years: 1930–1940. Boston, U.S.A.: Little, Brown & Company. ISBN 0-316-78703-5 (v. 2).

- "Austria - AUSTRIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- . Development of the Austrian identity Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Peter Utgaard, Remembering and Forgetting Nazism, (New York: Berghahn Books, 2003), 188–189. Frederick C. Engelmann, "The Austro-German Relationship: One Language, One and One-Half Histories, Two States", Unequal Partners, ed. Harald von Riekhoff and Hanspeter Neuhold (San Francisco: Westview Press, 1993), 53–54.

- Redaktion (13 March 2008). "Österreicher fühlen sich heute als Nation – 1938 – derStandard.at " Wissenschaft". Derstandard.at. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Europe's Rising Regionalism" (PDF). Toponline.org. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Germany and German Minorities in Europe" (PDF). Stefanwolff.com. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Fewer Ethnic Germans Immigrating to Ancestral Homeland". Migrationinformation.org. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "External causes of death in a cohort of Aussiedler from the former Soviet Union, 1990–2002". Egms.de. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- United Nations Population Fund: State of World Population 2006

- "Most Widely Spoken Languages". .ignatius.edu. 28 May 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Graphics: English replacing German as language of Science Nobel Prize winners. From J. Schmidhuber (2010), Evolution of National Nobel Prize Shares in the 20th Century Archived 27 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine at arXiv:1009.2634v1

- "Ethnologue: East Middle German". Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- Introduction to Old Yiddish literature, p. 72, Baumgarten and Frakes, Oxford University Press, 2005

- "Development of Yiddish over the ages", jewishgen.org

- Bleek, Wilhelm (2003). "Auslandsdeutsche". In Andersen, Uwe; Woyke, Wichard (eds.). Handwörterbuch des politischen Systems der Bundesrepublik (in German) (5th ed.). Opladen: Leske+Budrich. ISBN 9783810038654. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009.

- "Statistics Canada 2006". 2.statcan.ca. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011" (PDF). Stat.gov.pl. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Cascante, Manuel M. (8 August 2012). "Los menonitas dejan México". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 February 2013.

Los cien mil miembros de esta comunidad anabaptista, establecida en Chihuahua desde 1922, se plantean emigrar a la república rusa de Tartaristán, que se ofrece a acogerlos

- "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 188. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Deutsche Botschaft Guatemala - Startseite". diplo.de. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Distribution of the population of Ukraine`s regions by native language by Region, Indicated as a native language, Year and Contents". database.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Database of State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Searle, John. (1987). The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy, "Introduction". Wiley-Blackwell.

- Horst, Zuse."The Life and Work of Konrad Zuse". Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-18. Everyday Practical Electronics (EPE) Online. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- Automobile. Archived 29 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- The Zeppelin Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- Roberts, J. M. The New Penguin History of the World, Penguin History, 2002. Pg. 1014. ISBN 0-14-100723-0

- The Alfred B. Nobel Prize Winners, 1901–2003 Archived 10 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine History Channel from The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- Walhalla Ruhmes- und Ehrenhalle (in German), archived from the original on 2 October 2007, retrieved 3 October 2007

- Walhalla, official guide booklet. p. 3. Translated by Helen Stellner and David Hiley, Bernhard Bosse Verlag Regensburg, 2002

- "Germany's flailing music industry seeks new talent". Deutsche Welle. 2 February 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- BBC Radio 1 Documentary. Retrieved 2006, 10 December Archived 19 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Nederlanderse-entertainer-sin-Duitsland". Die Welt (in Dutch). 17 April 2010. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- 2006 FIAPF accredited Festivals Directory, International Federation of Film Producers Associations. Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- Plass, Ewald M., What Luther Says: An Anthology, St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959, 2:964.

- Schiller, Frederick, History of the Thirty Years' War, p.1, Harper Publishing

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Kirchenmitgliederzahlen" (PDF). Ekd.de. 31 December 2004. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

korrigierte Ausgabe

- Germany Info: Culture & Life: Sports Archived 30 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine Germany Embassy in Washington DC. Retrieved 28 December 2006

- Society Archived 20 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine The German Mission to the United States. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- Germany extends gay rights News24.com. Retrieved 25 November 2007. Archived 12 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Weinthal, Benjamin (31 August 2006). "He's Gay, and That's Okay". Gay City News. New York. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- Heckmann, Friedrich (2003). The Integration of Immigrants in European Societies: national differences and trends of convergence. Stuttgart: Lucius & Lucius. pp. 51ff. ISBN 978-3-8282-0181-1. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- How Germany won the World Cup of Nation Branding. BrandOvation. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- "2010 Anholt-GfK Roper Nation Brands Index" (Press release). GfK. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- "World warming to US under Obama, BBC poll suggests". BBC News. London. 19 April 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- BBC World Service Poll. BBC News. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- "Germans spend most on foreign trips: Industry group". The Economic Times. New Delhi. 10 March 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- Kesselman 2009, pp. 180.

- Motyl 2001, pp. 189–190.

- Forsythe, Diana. 1989. German identity and the problem of history. History and ethnicity, p.146

- "Das politische System in Österreich (The Political System in Austria)" (PDF) (in German). Vienna: Austrian Federal Press Service. 2000. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- Bauer, Kurt (2008). Nationalsozialismus: Ursprünge, Anfänge, Aufstieg und Fall (in German). Böhlau Verlag. p. 41. ISBN 9783825230760.

- Giloi, Eva (2011). Monarchy, Myth, and Material Culture in Germany 1750–1950. Cambridge University Press. pp. 161–162.

- Unowsky, Daniel L. (2005). The Pomp and Politics of Patriotism: Imperial Celebrations in Habsburg Austria, 1848–1916. Purdue University Press. p. 157.

- Brigitte Hamann, Hitler's Vienna: A Dictator's Apprenticeship, p. 282

- Suppan (2008). ′Germans′ in the Habsburg Empire. The Germans and the East. pp. 171–172.

- Mees, Bernard (2008). The Science of the Swastika. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9776-18-0.

- Alfred D. Low, The Anschluss Movement, 1918-1919, and the Paris Peace Conference, pp. 135-138

- Roderick Stackelberg, Hitler's Germany: Origins, Interpretations, Legacies, pp. 161-162

- "Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Austria; Protocol, Declaration and Special Declaration [1920] ATS 3". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Mary Margaret Ball, Post-war German-Austrian Relations: The Anschluss Movement, 1918-1936, pp. 18-19

- William L. Patch, Heinrich Bruning and the Dissolution of the Weimar Republic, pp. 120, 166, 190

- Ryschka, Birgit (1 January 2008). Constructing and Deconstructing National Identity: Dramatic Discourse in Tom Murphy's The Patriot Game and Felix Mitterer's In Der Löwengrube. Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631581117 – via Google Books.

- Fred C. Koch; Jacob Eichhorn (1978). The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. Penn State Press. pp. 151, 288. ISBN 0271038144.

- Eberhardt, Piotr (2006). Political Migrations in Poland 1939-1948. 8. Evacuation and flight of the German population to the Potsdam Germany (PDF). Warsaw: Didactica. ISBN 9781536110357. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2015.