George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River

George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River, which occurred on the night of December 25–26, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War, was the first move in a surprise attack organized by George Washington against the Hessian (German mercenaries in service of the British) forces in Trenton, New Jersey, on the morning of December 26. Planned in partial secrecy, Washington led a column of Continental Army troops across the icy Delaware River in a logistically challenging and dangerous operation. Other planned crossings in support of the operation were either called off or ineffective, but this did not prevent Washington from surprising and defeating the troops of Johann Rall quartered in Trenton. The army crossed the river back to Pennsylvania, this time laden with prisoners and military stores taken as a result of the battle.

Washington Crossing the Delaware, by George Caleb Bingham, 1856–71 | |

| Date | Night of December 25–26, 1776 |

|---|---|

| Location | Present-day Washington's Crossing National Historic Landmark, Pennsylvania and New Jersey |

| Participants | George Washington, Continental Army |

| Outcome | Battle of Trenton |

Washington's army then crossed the river a third time at the end of the year, under conditions made more difficult by the uncertain thickness of the ice on the river. They defeated British reinforcements under Lord Cornwallis at Trenton on January 2, 1777, and defeated his rear guard at Princeton on January 3, before retreating to winter quarters in Morristown, New Jersey.

The unincorporated communities of Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania, and Washington Crossing, New Jersey, are named in honor of this event.

Background

While 1776 had started well for the American cause with the evacuation of British troops from Boston in March, the defense of New York City had gone quite poorly. British General William Howe had landed troops on Long Island in August and had pushed George Washington's Continental Army completely out of New York by mid-November, when he captured the remaining troops on Manhattan.[1] The main British troops returned to New York for the winter season. They left mainly Hessian troops in New Jersey. These troops were under the command of Colonel Rall and Colonel Von Donop. They were ordered to small outposts in and around Trenton.[2] Howe then sent troops under the command of Charles Cornwallis across the Hudson River into New Jersey and chased Washington across New Jersey. Washington's army was shrinking because of expiring enlistments and desertions, and suffered from poor morale because of the defeats in the New York area. Most of Washington's army crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania north of Trenton, New Jersey, and destroyed or moved to the western shore all boats for miles in both directions. Cornwallis (under Howe's command), rather than attempting to immediately chase Washington further, established a chain of outposts from New Brunswick to Burlington, including one at Bordentown and one at Trenton, and ordered his troops into winter quarters.[3] The British were happy to end the campaign season when they were ordered to winter quarters. This was a time for the generals to regroup, re-supply, and strategize for the upcoming campaign season the following spring.[2]

Washington's army

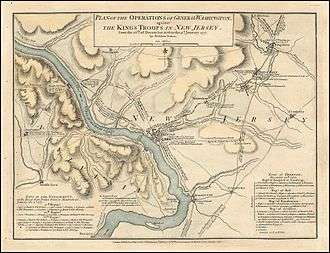

by William Faden

Washington encamped the army near McConkey's Ferry, not far from the crossing site. While Washington at first took quarters across the river from Trenton, he moved his headquarters on December 15 to the home of William Keith so he could remain closer to his forces. When Washington's army first arrived at McConkey's Ferry, he had four to six thousand men, although 1,700 soldiers were unfit for duty and needed hospital care. In the retreat across New Jersey, Washington had lost precious supplies and also lost contact with two important divisions of his army. General Horatio Gates was in the Hudson River Valley, and General Charles Lee was in western New Jersey with 2,000 men.[4] Washington had ordered both generals to join him, but Gates was delayed by heavy snows en route, and Lee, who did not have a high opinion of Washington, delayed following repeated orders, preferring to remain on the British flank near Morristown, New Jersey.[5][6]

Other problems affected the quantity and quality of his forces. Many of his men's enlistments were due to expire at the end of the year, and many soldiers were inclined to leave the army when their commission ended.[7] Several deserted before their enlistments were completed.[8] The pending loss of forces, the series of lost battles, the loss of New York, the flight of the Army along with many New Yorkers and the Second Continental Congress to Philadelphia, left many in doubt about the prospects of winning the war.[9] But Washington persisted. He successfully procured supplies and dispatched men to recruit new members of the militia,[10] which was successful partially because of British and Hessian mistreatment of New Jersey and Pennsylvania residents.[11]

The losses at Fort Lee and Washington placed a heavy toll on the Patriots. When they evacuated their forts, they were forced to leave behind critical supplies and munitions. Many troops had been killed or taken prisoner, and the morale of the remaining troops was low. Few believed that they could win the war and gain independence.[2]

Publication of The American Crisis

But the morale of the Patriot forces was boosted on December 19 when a new pamphlet titled The American Crisis written by Thomas Paine, the author of Common Sense, was published.[12]

These are the times that try men's souls; the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

Within a day of its publication in Philadelphia, General Washington ordered it to be read to all of his troops. It encouraged the soldiers and improved the tolerance of their difficult conditions.[13]

Reinforcements arrive

On December 20, General Lee's division of 2,000 troops arrived in Washington's camp under the command of General John Sullivan.[14] General Lee had been captured by the British on December 12, when he ventured too far outside the protection of his troops in search of more comfortable lodgings (or, according to rumors, a possible assignation).[15] Later that same day, General Gates' division arrived in camp, reduced to 600 whose enlistments had ended, and by the need to keep the northern frontier secure.[14] Soon after, another 1,000 militiamen from Philadelphia under Colonel John Cadwalader joined Washington.

With these reinforcements and smaller numbers of local volunteers who joined his forces, Washington's forces now totaled about 6,000 troops fit for duty. This total was then reduced by a large portion because some forces were detailed to guard the ferries at Dunk's Ferry (currently bordered by Neshaminy State Park in Bensalem Township, Pennsylvania and New Hope, Pennsylvania). Another group was sent to protect supplies at Newtown, Pennsylvania, and to guard the sick and wounded who had to remain behind when the army crossed the Delaware River.[11] This left Washington with about 2,400 men able to take offensive action against the Hessian and British troops in central New Jersey.[16]

This improvement in morale was aided by the arrival of some provisions, including much-needed blankets, on December 24.[17]

Planning the attack

General Washington had been considering some sort of bold move since arriving in Pennsylvania. With the arrival of Sullivan's and Gates' forces and the influx of militia companies, he felt the time was finally right for some sort of action. He first considered an attack on the southernmost British positions near Mount Holly, where a militia force had gathered. He sent his adjutant, Joseph Reed, to meet with Samuel Griffin, the militia commander. Reed arrived in Mount Holly on December 22, found Griffin to be ill and his men in relatively poor condition, but willing to make some sort of diversion.[18] (This they did with the Battle of Iron Works Hill the next day, drawing the Hessians at Bordentown far enough south that they would be unable to come to the assistance of the Trenton garrison.)[19] The intelligence gathered by Reed and others led Washington to abandon the idea of attacking at Mount Holly, preferring instead to target the Trenton garrison. He announced this decision to his staff on December 23, saying the attack would take place just before daybreak on December 26.[20]

Washington's final plan was for three crossings, with his troops, the largest contingent, to lead the attack on Trenton. A second column under Cadwalader was to cross at Dunk's Ferry and create a diversion to the south. A third column under Brigadier General James Ewing was to cross at Trenton Ferry and hold the bridge across the Assunpink Creek, just south of Trenton, in order to prevent the enemy's escape by that route. Once Trenton was secure, the combined army would move against the British posts in Princeton and New Brunswick. A planned fourth crossing, by men provided by General Israel Putnam to assist Cadwalader, was nixed after Putnam indicated he did not have enough men fit for the operation.[21]

Preparations for the attack began on December 23. On December 24, the boats used to bring the army across the Delaware from New Jersey were brought down from Malta Island near New Hope. They were hidden behind Taylor Island at McConkey's Ferry, Washington's planned crossing site; security was tightened at the crossing. A final planning meeting took place that day, with all of the general officers present. General orders were issued by Washington on December 25 outlining plans for the operation.[22]

Watercraft

A wide variety of watercraft were assembled for the crossing, primarily through the work of militia men from the surrounding counties in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and the assistance of the Pennsylvania Navy.

Captain Daniel Bray, along with Captain Jacob Gearhart and Captain Jacob Ten Eyck, were chosen by Washington to take charge of the boats used in the crossing, supervising the transport of infantry, cavalry, cannon. In addition to the large ferry vessels (which were big enough to carry large coaches, and likely served for carrying horses and artillery during the crossing), a large number of Durham boats were used to transport soldiers across the river. These boats were designed to carry heavy loads from the Durham Iron Works, featured high sides and a shallow draft, and could be poled across the river.[23][24]

The boats were operated by experienced watermen. Most prominent among them were the men of John Glover's Marblehead Regiment, a company of experienced seamen from Marblehead, Massachusetts. These men were joined by seamen, dockworkers, and shipbuilders from Philadelphia, as well as local ferry operators and boatsmen who knew the river well.[25]

Crossing

On the morning of December 25, Washington ordered his army to prepare three days' food and issued orders that every soldier be outfitted with fresh flints for their muskets. [26] He was also somewhat worried by intelligence reports that the British were planning their own crossing once the Delaware was frozen over. At 4 pm Washington's army turned out for its evening parade, where the troops were issued ammunition, and even the officers and musicians were ordered to carry muskets. They were told that they were departing on a secret mission.[27] Marching eight abreast in close formations and ordered to be as quiet as possible, they left the camp for McConkey's Ferry.[16] Washington's plan required the crossing to begin as soon as it was dark enough to conceal their movements on the river, but most of the troops did not reach the crossing point until about 6 pm, about ninety minutes after sunset.[28] The weather got progressively worse, turning from drizzle to rain to sleet and snow. "It blew a hurricane," recalled one soldier.[29]

Washington had given charge of the crossing logistics to his chief of artillery, Henry Knox. In addition to the crossing of large numbers of troops (most of whom could not swim), he had to safely transport horses and eighteen pieces of artillery over the river. Knox wrote that the crossing was accomplished "with almost infinite difficulty", and that its most significant danger was floating ice in the river.[30] One observer noted that the whole operation might well have failed "but for the stentorian lungs of Colonel Knox".[30] The unusually cold weather of the 1770s and the icy river were likely related to the Little Ice Age.[31]

Washington was among the first of the troops to cross, going with Virginia troops led by General Adam Stephen. These troops formed a sentry line around the landing area in New Jersey, with strict instructions that no one was to pass through. The password was "Victory or Death".[32] The rest of the army crossed without significant incident, although a few men, including Delaware's Colonel John Haslet, fell into the water.[33]

The amount of ice on the river prevented the artillery from finishing the crossing until 3 am on December 26. The troops were ready to march around 4 am.[34]

The two other crossings fared less well. The treacherous weather and ice jams on the river stopped General Ewing from even attempting a crossing below Trenton. Colonel Cadwalader crossed a significant portion of his men to New Jersey, but when he found that he could not get his artillery across the river he recalled his men from New Jersey. When he received word about Washington's victory, he crossed his men over again but retreated when he found out that Washington had not stayed in New Jersey.[35]

Attack

On the morning of December 26, as soon as the army was ready, Washington ordered it split into two columns, one under the command of himself and General Greene, the second under General Sullivan. The Sullivan column would take River Road from Bear Tavern to Trenton while Washington's column would follow Pennington Road, a parallel route that lay a few miles inland from the river. Only three Americans were killed and six wounded, while 22 Hessians were killed with 98 wounded.[36] The Americans captured 1,000 prisoners and seized muskets, powder, and artillery. [36][37]

Return to Pennsylvania

Following the battle, Washington had to execute a second crossing that was in some ways more difficult than the first. In the aftermath of the battle, the Hessian supplies had been plundered, and, in spite of Washington's explicit orders for its destruction, casks of captured rum were opened, so some of the celebrating troops got drunk,[38] probably contributing to the larger number of troops that had to be pulled from the icy waters on the return crossing.[39] They also had to transport the large numbers of prisoners across the river while keeping them under guard. One American acting as a guard on one of the crossings observed that the Hessians, who were standing in knee-deep ice water, were "so cold that their underjaws quivered like an aspen leaf."[40]

The victory had a marked effect on the troops' morale. Soldiers celebrated the victory, Washington's role as a leader was secured, and Congress gained renewed enthusiasm for the war.[2]

Third crossing

In a war council on December 27, Washington learned that all of the British and Hessian forces had withdrawn as far north as Princeton, something Cadwalader had learned when his militia company crossed the river that morning. In his letter, Cadwalader proposed that the British could be driven entirely from the area, magnifying the victory. After much debate, the council decided on action and planned a third crossing for December 29. On December 28 it snowed, but the weather cleared that night and it became bitter cold. As this effort involved most of the army, eight crossing points were used. At some of crossing points, the ice had frozen two to three inches (4 to 7 cm) thick and was capable of supporting soldiers, who crossed the ice on foot. At other crossings, the conditions were so bad that the attempts were abandoned for the day. It was New Year's Eve before the army and all of its baggage was back in New Jersey.[41] This was somewhat fortunate, as the enlistment period of John Glover's regiment (along with a significant number of others) was expiring at the end of the year, and many of these men, including most of Glover's, wanted to go home, where a lucrative privateering trade awaited them.[42] Only by offering a bounty to be paid immediately from Congressional coffers in Philadelphia did a significant number of men agree to stay with the army another six weeks.[43]

Washington then adopted a fortified position just south of the Assunpink Creek, across the creek from Trenton.[44] In this position he beat back one assault on January 2, 1777, which he followed up with a decisive victory at Princeton the next day. In the following days, the British withdrew to New Brunswick, and the Continental Army entered winter quarters in Morristown, New Jersey.[45]

Legacy

At the time of the crossing, Washington's army included a significant number of people who played important roles in the formation and early days of the United States of America. These included future President James Monroe, future Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall, Alexander Hamilton (a future Secretary of the Treasury), and Arthur St. Clair, who later served as President of the Continental Congress and Governor of the Northwest Territory.[46][47]

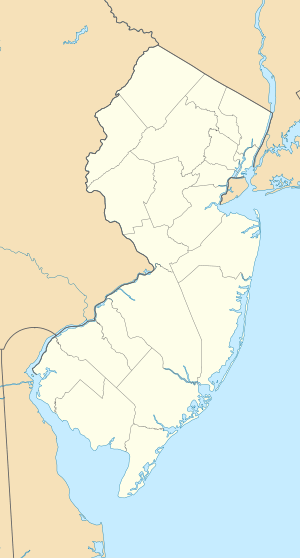

Both sides of the Delaware River where the crossing took place have been preserved, in an area designated as the Washington's Crossing National Historic Landmark. In this district, Washington Crossing Historic Park in Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania, preserves the area in Pennsylvania, and Washington Crossing State Park in Washington Crossing, New Jersey preserves the area in New Jersey.[48] The two areas are connected by the Washington Crossing Bridge.[49]

In 1851, the artist Emmanuel Leutze created the painting, Washington Crossing the Delaware, an idealized and inspirational portrayal of the crossing.[50] Fictional portrayals in film of the crossing have also been made, with perhaps the most notable recent one being The Crossing, a 2000 television movie starring Jeff Daniels as George Washington.[51]

See also

- Prince Whipple – According to legend, Prince Whipple accompanied General Whipple and George Washington in the crossing of the Delaware River. Some believe that Whipple is the black man portrayed fending off ice with an oar at Washington's knee in the painting Washington Crossing the Delaware.[52]

- Conrad Heyer – The earliest-born person to have been photographed, Heyer was also the only man who crossed the Delaware River with Washington's army to have been photographed.

- "Washington Crossing the Delaware" (sonnet)

Notes

- Dwyer 1983, p. 5.

- "Washington's Crossing". Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- The retreat is recounted in detail by Dwyer, pp. 24–112

- Ketchum 1999, pp. 208–209, 265.

- Ketchum 1999, pp. 249–254, 265.

- Dwyer 1983, p. 130.

- Fischer 2006, pp. 264, 270.

- Dwyer 1983, p. 120.

- Fischer 2006, p. 136.

- Fischer 2006, pp. 150–152.

- Fischer 2006, pp. 191–195.

- Ketchum 1999, pp. 210–211.

- Ketchum 1999, p. 295.

- Ketchum 1999, p. 290.

- Dwyer 1983, pp. 141–145.

- Fischer 2006, p. 208.

- Fischer 2006, p. 156.

- Dwyer 1983, p. 210.

- Dwyer 1983, pp. 216–217.

- Dwyer 1983, pp. 211–212.

- Dwyer 1983, pp. 212–213.

- Ketchum 1999, p. 293.

- Fischer 2006, p. 216.

- Michael W. Robbins, "The Durham Boat" MHQ: Quarterly Journal of Military History (Winter 2015) 27#2 pp 26-28.

- Fischer 2006, p. 217.

- Fischer 2006, p. 206.

- Fischer 2006, p. 207.

- Fischer 2006, p. 210.

- Fischer 2006, p. 212.

- Fischer 2006, p. 218.

- Glenn, William Harold (1996). "Integrating Teaching About the Little Ice Age with History, Art, and Literature". Journal of Geoscience Education. 44: 361–365. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

Joseph P. Stoltman (20 October 2011). 21st Century Geography. SAGE. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4129-7464-6.

Anthony N. Penna (2010). The Human Footprint: A Global Environmental History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-4051-8772-5.

Donald R. Prothero (13 July 2006). After the Dinosaurs: The Age of Mammals. Indiana University Press. p. 304. ISBN 0-253-00055-6. - Fischer 2006, p. 220.

- Fischer 2006, p. 219.

- Washington, George. "George Washington to Continental Congress, December 27, 1776". George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741–1799: Series 3a Varick Transcripts. The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- Ketchum 1999, pp. 321–322.

- Crocker 2006, p. 59.

- McCullough 2005, p. 281. (There were at least 1,400 Hessians: 900 were captured, 500 escaped, 21 were killed, and 90 were wounded.).

- Fischer 2006, p. 256.

- Fischer 2006, p. 257.

- Fischer 2006, p. 259.

- Fischer 2006, pp. 265–268.

- Fischer 2006, p. 270.

- Fischer 2006, pp. 273–275.

- Ketchum 1999, p. 276.

- Ketchum 1999, pp. 286–322.

- Fischer (2006), pp. 222, 223, 339.

- Bennett (2006), p. 89.

- C. E. Shedd, Jr. (August 1, 1960). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Washington Crossing State Park" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying two photos, from 1960

- Washington Crossing Toll Supported Bridge

- Fischer 2006, pp. 1–6.

- Washington Crossing Historic Park – Frequently Asked Questions

- William C. Nell, in his 1851 book Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

Further reading

- Bennett, William John (2006). America: From the age of discovery to a world at war, 1492–1914. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-1-59555-055-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crocker, H. W., III (2006). Don't Tread on Me. New York: Crown Forum. ISBN 978-1-4000-5363-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dwyer, William M (1983). The Day is Ours!. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-11446-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fischer, David Hackett (2006). Washington's Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518159-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ketchum, Richard (1999). The Winter Soldiers: The Battles for Trenton and Princeton. Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-6098-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCullough, David (2005). 1776. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2671-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robbins, Michael W. "The Durham Boat" MHQ: Quarterly Journal of Military History (2015) 27#2 pp 26–28, the boat Washington used.

- "Across the Delaware". Liberty's Kids. Episode 119. PBS.

- "Washington Crossing Toll Supported Bridge". Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission. Archived from the original on 2007-10-05. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- "Washington Crossing Historic Park". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Archived from the original on 2010-03-30. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- "Washington Crossing Historic Site – Frequently Asked Questions". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Archived from the original on 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- "Washington Crossing State Park". New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Washington's crossing of the Delaware River. |