Geisha

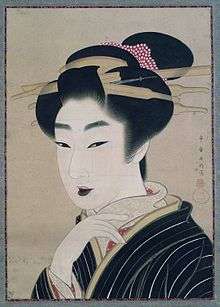

Geisha (芸者) (/ˈɡeɪʃə/; Japanese: [ɡeːɕa]),[1][2] geiko (芸子), or geigi (芸妓) are Japanese women who entertain through performing the ancient traditions of art, dance and singing, and are distinctively characterized by their wearing of kimono and oshiroi makeup.

Contrary to popular belief, geisha are not the Eastern equivalent of a prostitute, a misconception originating in the West due to interactions with Japanese oiran (courtesans), whose traditional attire is similar to that of geisha.

Terms

The word "geisha" consists of two kanji, 芸 (gei) meaning "art" and 者 (sha) meaning "person" or "doer". The most literal translation of geisha into English would be "artist", "performing artist", or "artisan". Another regional term for geisha is geiko (芸妓), which translates specifically as "woman of art". This term is used to refer to geisha from Western Japan, including Kyoto and Kanazawa.

Apprentice geisha are called maiko (舞妓), lit. "woman of dance". In some regions of Japan, such as Tokyo, apprentices are referred to as hangyoku (半玉), "half-jewel", a euphemistic term referring to apprentices receiving half the wage of a full geisha - payment for geisha at one time having been referred to by terms such as "flower money" or "jewel money".[3][4]

The white make-up and elaborate kimono and hair of a maiko is the popular image held of geisha. A woman entering the geisha community does not have to begin as a maiko, having the opportunity to begin her career as a full geisha if considered to be either too old to debut as a maiko or skilled enough to debut as a geisha. Despite this, a year's training is usually involved before debuting professionally as either.

On average, Tokyo apprentices (who typically begin at 18) are slightly older than their Kyoto counterparts (who usually start at 15).[5] Historically, geisha often began the earliest stages of their training at a very young age, sometimes as early as 6 years old. The early shikomi (in-training) and minarai (learning by observation) stages of geisha training lasted for years (shikomi) and months (minarai) respectively, which is significantly longer than in contemporary times. A girl is often a shikomi for up to a year while the modern minarai period is simply one month.

It is still said that geisha inhabit a separate world which they call the karyūkai or "the flower and willow world". Before they disappeared, courtesans were the colourful "flowers" and the geisha the willows in this phrase, ostensibly due to their subtlety, strength, and grace.[6]

History

Origins

In the early stages of Japanese history, there were female entertainers: Saburuko (serving girls) were mostly wandering girls whose families were displaced from struggles in the late 600s. Some of these saburuko girls sold sexual services, while others with a better education made a living by entertaining at high-class social gatherings. After the imperial court moved the capital to Heian-kyō (Kyoto) in 794 the conditions that would form geisha culture began to emerge, as it became the home of a beauty-obsessed elite.[7] Skilled female performers, such as Shirabyōshi dancers, thrived.

Traditional Japan embraced sexual delights and men were not constrained to be faithful to their wives.[8] The ideal wife was a modest mother and manager of the home; by Confucian custom love had secondary importance. For sexual enjoyment and romantic attachment, men did not go to their wives, but to courtesans. Walled-in pleasure quarters known as yūkaku (遊廓、遊郭) were built in the 16th century,[9] and in 1617 the shogunate designated "pleasure quarters", outside of which prostitution would be illegal,[10] and within which yūjo ("play women") would be classified and licensed. The highest yūjo class was the geisha's predecessor, called tayuu, a combination of actress and prostitute, originally playing on stages set in the dry Kamo riverbed in Kyoto. They performed erotic dances and skits, and this new art was dubbed kabuku, meaning "to be wild and outrageous". The dances were called "kabuki", and this was the beginning of kabuki theater.[10]

18th-century emergence of the geisha

These pleasure quarters quickly became glamorous entertainment centers, offering more than sex. The highly accomplished courtesans of these districts entertained their clients by dancing, singing, and playing music. Some were renowned poets and calligraphers. Gradually, they all became specialized and the new profession, purely of entertainment, arose. It was near the turn of the eighteenth century that the first entertainers of the pleasure quarters, called geisha, appeared. The first geishas were men, entertaining customers waiting to see the most popular and gifted courtesans (oiran).[10]

The forerunners of the female geisha were the teenage odoriko ("dancing girls"):[11] expensively trained as chaste dancers-for-hire. In the 1680s, they were popular paid entertainers in the private homes of upper-class samurai,[12] though many had turned to prostitution by the early 18th century. Those who were no longer teenagers (and could no longer style themselves odoriko[13]) adopted other names—one being "geisha", after the male entertainers. The first woman known to have called herself geisha was a Fukagawa prostitute, in about 1750.[14] She was a skilled singer and shamisen player named Kikuya who was an immediate success, making female geisha extremely popular in 1750s Fukagawa.[15] As they became more widespread throughout the 1760s and 1770s, many began working only as entertainers (rather than prostitutes), often in the same establishments as male geisha.[16]

Geisha in the 19th century to present day

The geisha who worked within the pleasure quarters were strictly forbidden from selling sex in order to protect the business of the oiran who held high status in society at the time. Geisha were forbidden from wearing particularly flashy hairpins or kimono, and if an oiran accused a geisha of stealing her customers and business, an official enquiry would be opened and an investigation held.[17] At various points throughout the Edo period, geisha found themselves affected by various reforms aimed at limiting or shutting down the pleasure quarters, leading to geisha being confined to working within various "red light" districts at times, such as Shimabara in Tokyo. However, these reforms were often not consistent, and were at various times repealed.

By 1800, being a geisha was understood to be a female occupation (though a handful of male geisha still work today). Whilst licensed courtesans existed to meet the sexual needs of men, machi geisha (town geisha) began to carve out a separate niche as artists and erudite, worldly female companions. The introduction of various edicts on dress in the 1720s onwards, coupled with the rise of iki saw geisha enjoy a rise in popularity. Eventually, the gaudy oiran began to fall out of fashion, becoming less popular than the chic modern geisha;[10] this was a trend that continued until the eradication of legal prostitution in Japan.

By the 1830s, geisha were considered some of the leaders of fashion and style in Japanese society, and were emulated by women of the time.[18] Many trends that geisha started became widely popular and continue to this day; the wearing of haori by women, for example, was begun by geisha in the Tokyo hanamachi of Fukugawa in the early 1800s.

There were many different classifications and ranks of geisha, not all of them formally recognised. Some geisha would have sex with their male customers, whereas others would not. Various terms arose to describe the distinctions; kuruwa geisha, for example, described geisha who slept with customers as well as entertaining with their skills in the performing arts. This differed from yujō (prostitute) and jorō (whore), who only slept with customers, and from machi geisha, who were exclusively entertainers (though some machi geisha still slept with the men they entertained).[19]

Pre-war and wartime geisha

Prostitution in Japan was legal until the 1957 Prohibition of Prostitution Law (売春防止法, Baishun Bōshi Hō) was passed, and so was practiced legally throughout Japan until this point, though various edicts up until this point had gradually restricted and changed the way that prostitution was legally conducted and regulated.

Before this time, World War II had brought a huge decline in the number of practicing geisha. In the years leading up to 1944, geisha had seen a decline in customers and income due to the war effort, though they themselves had contributed through the efforts of the various Geisha Associations throughout the country. In 1944, all geisha districts were closed, and geisha themselves conscripted into the war effort proper. Many geisha found themselves working in factories, or found work elsewhere through customers and patrons.

During and after the war, the geisha name lost some status, as some prostitutes began referring to themselves as "geisha girls" to members of the American military occupying Japan.[17]

Post-war geisha

In 1945, the karyūkai saw restrictions on its practices lifting, with teahouses, bars and okiya allowed to open once again. Though many geisha did not return to the hanamachi post-war, having found stable work elsewhere, it was evident that work as a geisha was still lucrative; geisha numbers began to pick up quickly, with the largest population of geisha (35% of the total) being aged 20-24, with many retiring from the profession in their mid-twenties - a trend carried over from the pre-war hanamachi:

I showed the mother of the Yamabuki [okiya, in 1975] some statistics on the age distribution of the geisha population in the 1920s. She remarked on the big dip in figures when women reached the age of twenty-five. "In those days, when you found yourself a patron you could stop working. If you were lucky you would be set up in your own apartment and have a life of leisure, taking lessons when you wanted to for your own enjoyment...I think it's pretty unusual nowadays for a geisha to stop working when she gets a patron."[20]

The status of geisha in wider society underwent a drastic change post-war; having once been arbiters of change and fashion, the 1920's and 30's had seen a great deal of discussion surrounding the place of geisha in a rapidly Westernising Japanese society. Some geisha had begun to experiment with wearing Western clothing to their engagements, experimenting with Western-style dancing and serving cocktails to customers instead of sake. The image of "modern" pre-war geisha had been viewed by some as unprofessional, or a betrayal of the profession's image; however, the incumbent pressures of the war rapidly turned the tide against Westernisation, and such experiments were abandoned.

Post-war, geisha unspokenly rejected Western influence, reverting unanimously to wearing kimono and keeping the more traditional arts of playing the shamisen, singing and dancing. Nonetheless, this had the knock-on effect of dealing the final blow to the profession's reputation as fashionable in the wider societal sense, instead rendering their image "protectors of tradition" in terms of their methods of entertaining customers.[17]

After Japan lost the war, geisha dispersed and the profession was in shambles. When they regrouped during the Occupation and began to flourish in the 1960s during Japan's postwar economic boom, the geisha world changed. In modern Japan, girls are not sold into indentured service. Nowadays, a geisha's sex life is her private affair.

— Liza Dalby, Do They or Don't They?[21]

Post-war geisha experienced a greater benefit in rights within the profession and in wider society, with the introduction of the Prostitution Prevention Law in 1956 at least serving to benefit geisha through the outlawing of mizuage, a practice undergone, willingly, coercively or through force, by some maiko in pre-war Japan.[17]

Post-war misconceptions of mizuage being a common practice pre- and post-war mostly stem from American GIs encountering genuine prostitutes, not geisha, labelling their services as "mizuage" and themselves as "geisha". Having little previous experience with geisha culture, it is likely that foreign forces were unable to tell the difference between a geisha and a prostitute, as both commonly wore kimono when working; this misconception continues into the present day.[22]

From the 1930s onwards, and particularly within post-war Japan, the rise of the jokyū bar hostess began to overshadow geisha as the premiere profession of entertainment at parties and outings for men.[20]:84 In 1959, the Standard-Examiner reported the plight of then-contemporary geisha culled from an article written for the magazine Bungei Shunju by Japanese businessman Tsûsai Sugawara; Sugawara stated that girls now "prefer[red] to become dancers, models, and cabaret and bar hostesses rather than start [the] training in music and dancing at the age of seven or eight" necessary to become geisha at the time.[23]

Compulsory education laws passed in the 1960s also made the traditions of training from a young age to become a geisha difficult to conduct, leading to a decline in women entering the profession, the pre-requisite qualities of training in the arts becoming more difficult to come by.[24]

By 1975, the average age of a geisha in the Pontochō district of Kyoto was roughly 39, with the vast majority of the geisha population in the district spanning ages 35-49.[20] Though fewer geisha were in their fifties than in their 20s, the population of geisha over 60 was surprisingly high, roughly equivalent to younger women within the profession; this is, in part, due to the fact that geisha no longer retired young when they found a patron, and were less likely than other women of the same age to have children, grandchildren and a wider family, the karyukai instead being the closest and most familiar kin to many.

Present day geisha

In the present day, all maiko debut roughly aged 18, with most okiya requiring a girl to finish at the very least high school before debuting. A trainee entering the profession will commonly have at least some background in the arts before this; however, it is not uncommon for trainees to have little previous experience. With the advent of social media and wider TV, documentaries and books about geisha commonly inspire young women to join the profession, with the geisha Satsuki - officially deemed the most popular geisha in Gion for a period of seven years - having been one such person:[25]

[Geisha] Satsuki first took an interest in the kagai [lit. "five geisha districts" - name for geisha quarters in Kyoto] while a middle school student in Osaka, at around the age of 14, after seeing a documentary about a maiko’s training. “I already had heard of maiko, but it was when I saw the documentary that I thought – I want to do that.”

Ranking

Though regional hanamachi usually are not large enough to be seen as having a hierarchy, in Kyoto, the differing hanamachi - known as the Gokagai (lit. "five hanamachi") - are unofficially ranked within Kyoto's karuykai. Gion Kobu, Pontochō and Kamishichiken are seen as having the highest prestige,[26] with Gion Kobu being placed at the top; below these three are Gion Higashi and Miyagawa-cho.[27] The more prestigious hanamachi are frequented by powerful businessmen and politicians.[10]

In the 1970s, Kyoto was described as having rokkagai (lit. "six hanamachi"), as the district of Shimabara was still active as a geisha district. However, no geisha are active in Shimabara in the 21st century, and it now hosts tayū re-enactors instead.[28]

Regional geisha districts are seen as having less prestige than those in Kyoto, viewed as being the pinnacle of tradition in the karyukai. Geisha in onsen towns such as Atami may also be seen as less prestigious, as instead of being called upon specially by customers already acquainted, they are instead employed by hotels who organise parties and banquets for travellers and holidaymakers who do not know them. Nevertheless, all geisha, regardless of region or district, are trained in the traditional arts, making the distinction of prestige one of history and tradition.

Stages of training

Traditionally, geisha began their training at a young age. Some girls were bonded to geisha houses (okiya) as children. Daughters of geisha were often brought up as geisha themselves, usually as the successor (atotori, meaning "heir" or "heiress" in this particular situation) or daughter-role (musume-bun) to the okiya. Successors, however, were not always blood relations.

In the present day, geisha no longer begin their training at a young age, and usually debut as maiko around the age of 17 or 18. Before this time, they may live at the okiya as shikomi - essentially a trainee trainee, learning all the necessary skills to become a maiko, as well as attending to the needs of the house and learning to live with her geisha sisters and within the karyūkai.

A maiko is an apprentice and is therefore bonded under a contract to her okiya. The okiya will usually supply her with food, board, kimono, obi, and other tools of her trade, but a maiko may decide to fund everything herself from the beginning with either a loan or the help of an outside guarantor.[4]

In both cases, a maiko's training is very expensive, and this debt must be repaid over time to either the okiya or her guarantor with the earnings she makes. This repayment may continue after graduation to geishahood, and only when her debts are settled can a geisha claim her entire wages and work independently (if loaning from the okiya).

After this point, however, she may chose to stay on living at her okiya, must still be affiliated to one to work, and even living away from the okiya, will usually commute there to begin her working evening.[4][7][note 1][note 2]

A maiko will start her formal training on the job as a minarai - which literally means "learning by watching" - at an ozashiki (お座敷, a geisha party), where she will sit and observe as the other maiko and geisha interact with customers. In this way, a trainee gains insights into the nature of the job, following the typical nature of traditional arts apprenticeships wherein an apprentice is expected to learn almost entirely through observation.

Although geisha at the stage of minarai training will attend parties, they will not participate on an involved level, and are instead expected to sit quietly. Trainees can be hired for parties, but are usually uninvited - though welcomed - guests, brought along by their symbolic older sister as a way of introducing a new trainee to patrons of the karyūkai.

Minarai usually charge just a third of the fee a typical geisha would charge, and typically work within just one particular tea house, known as the minarai-jaya - learning from the mother (proprietress) of the house. The minarai stage of training involves learning techniques of conversation, typical party games, and proper decorum and behaviour within banquets and parties. This stage lasts only about a month or so.[31]

After the minarai period, a trainee will make her official debut (misedashi) and officially become a maiko. Maiko (literally "dance girl") are apprentice geisha, and this stage can last for up to 5 years. Maiko learn from their senior maiko and geiko mentors. The onee-san and imouto-san (senior/junior, literally "older sister/younger sister") relationship is important. The onee-san, any maiko or geiko who is senior to a girl, teaches her maiko everything about working in the hanamachi. The onee-san will teach her proper ways of serving tea, playing shamisen, dancing, casual conversation and more.

There are three major elements of a maiko's training. The first is the formal arts training. This takes place in schools which are found in every hanamachi. The second element is the entertainment training which a trainee learns at various tea houses and parties by observing her onee-san. The third is the social skill of navigating the complex social web of the hanamachi; formal greetings, gifts, and visits are key parts of the social structure of the karyūkai, and crucial for the support network necessary to support a trainee's eventual debut as a geisha.

Maiko are considered one of the great sights of Japanese tourism, and look very different from fully qualified geisha. They are at the peak of traditional Japanese femininity. The scarlet-fringed collar of a maiko's kimono hangs very loosely in the back to accentuate the nape of the neck, which is considered a primary erotic area in Japanese sexuality. She wears the same white makeup for her face on her nape, leaving two or sometimes three stripes of bare skin exposed. Her kimono is bright and colourful with an elaborately tied obi hanging down to her ankles. She takes very small steps and wears traditional wooden shoes called okobo which stand nearly ten centimeters high.[7] There are five different hairstyles that a maiko wears, that mark the different stages of her apprenticeship.

The nihongami hairstyle with kanzashi hair ornaments are most closely associated with maiko,[32] who spend hours each week at the hairdresser and sleep on special pillows to preserve the elaborate styling.[33] Maiko can develop a bald spot on their crown caused by the stress of wearing these hairstyles almost every day, but in the present day, this is less likely to happen due to the later age at which maiko begin their apprenticeship.

Around the age of 20–21, the maiko is promoted to a full-fledged geisha in a ceremony called erikae (turning of the collar).[34][35] This could happen after three to five years of her life as a maiko or hangyoku, depending on at what age she debuted. Geisha remain as such until they retire.

Female dominance in geisha society

The biggest industry in Japan is not shipbuilding, producing cultured pearls, or manufacturing transistor radios or cameras. It is entertainment.

— Boye De Mente, Some Prefer Geisha[36]

Despite long-held connotations between sex and geisha, a geisha's sex and love life is usually distinct from her professional life. A successful geisha can entertain her male customers with music, dance, and conversation.

Geishas are not submissive and subservient, but in fact they are some of the most financially and emotionally successful and strongest women in Japan, and traditionally have been so.

— Iwasaki Mineko, Geisha, A Life[37]

Most geisha are single women, though may have lovers or boyfriends over time. In previous decades, a married geisha would not have been able to continue working within the profession; however, in the present day, some geisha are married and continue to work. These geisha are usually found in regions outside of Kyoto, whose highly-traditionalist hanamachi would be unlikely to allow a married geisha to continue working.

There is currently no western equivalent for a geisha—they are truly the most impeccable form of Japanese art.

— Kenneth Champeon, The Floating World[38]

Relationships with male guests

The appeal of a high-ranking geisha to her typical male guest has historically been very different from that of his wife. The ideal geisha showed her skill, while the ideal wife was modest. The ideal geisha seemed carefree, the ideal wife somber and responsible. Historically, geisha did sometimes marry their clients, but marriage necessitated retirement, as there were never married geisha.

Geisha may gracefully flirt with their guests, but they will always remain in control of the hospitality. Over their years of apprenticeship they learn to adapt to different situations and personalities, mastering the art of the hostess.[39]

Geisha as a women-centered society

Women in the geisha society are some of the most successful businesswomen in Japan. Inside the hanamachi, women, with the sole exclusions of male kimono dressers, some hairstylists and other craftspeople, run everything; new geisha are trained for the most part by their symbolic mothers and older sisters, and engagements are arranged through the mother of the house.[40][41] Without the impeccable business skills of the female tea house owners, the world of geisha would cease to exist. The tea house owners are entrepreneurs, whose service to the geisha is highly necessary for the society to run smoothly. Infrequently, men take contingent positions such as hair stylists,[42] dressers (dressing a maiko requires considerable strength) and accountants,[17] but men have a limited role in geisha society.

The geisha system was founded, actually, to promote the independence and economic self-sufficiency of women. And that was its stated purpose, and it actually accomplished that quite admirably in Japanese society, where there were very few routes for women to achieve that sort of independence.

— Mineko Iwasaki in interview, Boston Phoenix[43]

Historically, the majority of women were wives who did not work outside of their familial duties. A young geisha, however, could repay her debts, become independent and work as such after making her debut. Becoming a geisha, therefore, was one method for women to support themselves without becoming a wife.[44] Women run the geisha houses, they are teachers, they run the tea houses, they recruit aspiring geisha, and they keep track of a geisha's finances. Moreover, the geisha who has been chosen as an atotori (heir) of the Ggisha house would live there and run the business throughout her career until the next generation.[45] The only major role men play in geisha society is that of guest, though women sometimes take that role as well.[42]

Historically, Japanese feminists have seen geisha as exploited women, but some modern geisha see themselves as liberated feminists:[46] "We find our own way, without doing family responsibilities. Isn't that what feminists are?"[17]

Modern geisha

Modern geisha still live in traditional geisha houses called okiya in areas called hanamachi (花街 "flower streets"), particularly during their apprenticeship. Many experienced geisha are successful enough to choose to live independently. The elegant, high-culture world that geisha are a part of is called karyūkai (花柳界 "the flower and willow world").

Before the twentieth century, geisha training began when a girl was around the age of six. Now, girls must go to school until they are 15 years old and have graduated from middle school and then make the personal decision to train to become a geisha. Young women who wish to become geisha now most often begin their training after high school or even college. Many more women begin their careers in adulthood.[47]

Geisha still study traditional instruments: the shamisen, shakuhachi, and drums, as well as learn games,[48] traditional songs, calligraphy,[49] Japanese traditional dances (in the nihonbuyō style), tea ceremony, literature, and poetry.[50][51]

By watching other geisha, and with the assistance of the owner of the geisha house, apprentices also become skilled dealing with clients and in the complex traditions surrounding selecting and wearing kimono, a floor length silk robe embroidered with intricate designs which is held together by a sash at the waist which is called an obi.[52][53]

In modern Japan, geisha and their apprentices are now a rare sight outside hanamachi or chayagai (茶屋街, literally "tea house district", often referred to as "entertainment district"). In the 1920s, there were over 80,000 geisha in Japan,[54][55] but today, there are far fewer. Most common sightings are of tourists who pay a fee to be dressed up as a maiko.[56]

A sluggish economy, declining interest in the traditional arts, the exclusive nature of the flower and willow world, and the expense of being entertained by geisha have all contributed to the tradition's decline.[57] However, the flower and willow world has seen a resurgence in new members over the last 10 years due to the accessibility that the internet has provided for young girls wanting to know more about the profession and not needing a formal introduction to an okiya.

Geisha are often hired to attend parties and gatherings, traditionally at ochaya (お茶屋, literally "tea houses") or at traditional Japanese restaurants (ryōtei).[53] The charge for a geisha's time, which used to be determined by measuring a burning incense stick, is called senkōdai (線香代, "incense stick fee") or gyokudai (玉代 "jewel fee"). Now they are flat fees charged by the hour. In Kyoto, the terms ohana (お花) and hanadai (花代), meaning "flower fees", are preferred. The okasan makes arrangements through the geisha union office (検番 kenban), which keeps each geisha's schedule and makes her appointments both for entertaining and for training.

Non-Japanese geisha

Since the 1970s, non-Japanese have also become geisha. Liza Dalby, an American national, worked briefly with geisha in the Pontocho district of Kyoto as part of her doctorate research, although she did not formally debut as a geisha herself.[58][59] The traditionalist district of Gion, Kyoto does not accept non-Japanese nationals to train nor work as geisha.

Other foreign nationals who have completed training and worked as geisha in Japan include the following:

- Kimicho - (Sydney Stephens), an American national who worked as a geisha in the Shinagawa district of Tokyo. Stephens debuted in August of 2015, but left the profession in 2017 for personal reasons.[60]

- Fukutarō — (Isabella), a Romanian national worked in the Izu-Nagaoka district of Shizuoka Prefecture. She began her apprenticeship in April 2010 and debuted a year later in 2011.[61]

- Ibu — (Eve), a geiko of Ukrainian descent working in Anjō district of Aichi Prefecture, who first became interested in being a geisha in 2000, after visiting Japan for a year to study traditional dance.[62]

- Juri — (Maria), a Peruvian geiko working in the resort town of Yugawara in Kanagawa Prefecture.[63]

Public performances

While traditionally geisha have led a cloistered existence, in recent years they have become more publicly visible, and entertainment is available without requiring the traditional introduction and connections.

The most visible form of this are public dances, or odori (generally written in traditional kana spelling as をどり, rather than modern おどり), featuring both maiko and geisha. All the Kyoto hanamachi hold these annually (mostly in spring, with one exclusively in autumn), dating to the Kyoto exhibition of 1872,[68] and there are many performances, with tickets being inexpensive, ranging from around 1500 yen to 4500 yen – top-price tickets also include an optional tea ceremony (tea and wagashi served by maiko) before the performance;[69] see Kyoto hanamachi and Kanazawa hanamachi for a detailed listing. Other hanamachi also hold public dances, including some in Tokyo, but have fewer performances.[69]

Another notable event is that the geisha (including maiko) of the Kamishichiken district in northwest Kyoto serve tea to 3,000 guests on February 25 in an annual open-air tea ceremony (野点, nodate) at the plum-blossom festival (梅花祭, baikasai) at Kitano Tenman-gū shrine.[70][71] As of 2010, these geishas also serve beer in a beer garden at Kamishichiken Kaburenjo Theatre during summer months (July to early September);[72][73][74] another geisha beer garden is available at the Gion Shinmonso ryokan in the Gion district.[72] These beer gardens also feature traditional dances by the geisha in the evenings.

Arts

Pre-WW2, geisha began their formal study of music and dance very young, having typically joined an okiya aged 11-13 years old. In the present day, labour laws stipulate that that apprentices only join an okiya aged 18; Kyoto is legally allowed to take on recruits at a younger age, 15-17.[75]

Before this time, new recruits are expected to have some interest and experience in the arts, but this now relies on the individual in question, rather than being a strict prerequisite. Some okiya will take on recruits with no previous experience, and some young geisha will be expected to start lessons from the very beginning.[76]

Geisha can and do work into their eighties and nineties,[75] and are still expected to train regularly, even after seventy years of experience,[77] though lessons may only be put on a few times a month.

The dance performed by geisha has evolved from dance styles performed on the nōh and kabuki stages. The "wild and outrageous" dances transformed into a more subtle, stylized, and controlled form of dance. Every dance uses gestures to tell a story and only a connoisseur can understand the subdued symbolism. For example, a tiny hand gesture represents reading a love letter, holding the corner of a handkerchief in the mouth represents coquetry and the long sleeves of the elaborate kimono are often used to symbolize dabbing tears.[10]

The dances are accompanied by traditional Japanese music. The primary instrument is the shamisen. The shamisen was introduced to the geisha culture in 1750 and has been mastered by female Japanese artists for years.[78] This shamisen, originating in Okinawa, is a banjo-like three-stringed instrument that is played with a plectrum. It has a very distinct, melancholy sound that is often accompanied by flute. The instrument is described as "melancholy" because traditional shamisen music uses only minor thirds and sixths.[78] All geisha must learn shamisen-playing, though it takes years to master. Along with the shamisen and the flute, geisha also learned to play a ko-tsuzumi, a small, hourglass-shaped shoulder drum, and a large floor taiko (drum). Some geisha would not only dance and play music, but would write beautiful, melancholy poems. Others painted pictures or composed music.[10]

Geisha and prostitution

Sheridan Prasso wrote that Americans had "an incorrect impression of the real geisha world ... geisha means 'arts person' trained in music and dance, not in the art of sexual pleasure".[79] K. G. Henshall wrote that the geisha's purpose was "to entertain their customer, be it by dancing, reciting verse, playing musical instruments, or engaging in light conversation. Geisha engagements may include flirting with men and playful innuendos; however, clients know that nothing more can be expected. In a social style that is common in Japan, men are amused by the illusion of that which is never to be."[80] They are comparable to the concept of an 'accomplished woman' in Regency era England.

In 1872, shortly after the Meiji Restoration, the new government passed a law liberating "prostitutes (shōgi) and geisha (geigi)". These terms were a subject of controversy because the difference between geisha and prostitutes remained ambiguous.[81] Some officials thought that prostitutes and geisha worked at different ends of the same profession—selling sex— and that all prostitutes should henceforth be called "geisha". In the end, the government decided to maintain a line between the two groups, arguing that geisha were more refined and should not be soiled by association with prostitutes.[82]

Also, geisha working in onsen towns such as Atami are dubbed onsen geisha. Onsen geisha have been given a bad reputation due to the prevalence of prostitutes in such towns who market themselves as "geisha". In contrast to these "one-night geisha", the true onsen geisha are competent dancers and musicians. However, the autobiography of Sayo Masuda, an onsen geisha who worked in Nagano Prefecture in the 1930s, reveals that in the past, such women were often under intense pressure to sell sex.[3]

Personal relationships and danna partnership

Geisha are portrayed as unattached. Formerly those who chose to marry had to retire from the profession, though today, some geisha are allowed to marry. It was traditional in the past for established geisha to take a danna, or patron. A danna was typically a wealthy man, sometimes married, who had the means to support the very large expenses related to a geisha's traditional training and other costs. This sometimes occurs today as well, but very rarely. A geisha and her danna may or may not be in love, but intimacy is never viewed as a reward for the danna's financial support. While it is true that a geisha is free to pursue personal relationships with men she meets through her work, such relationships are carefully chosen and unlikely to be casual. A hanamachi tends to be a very tight-knit community and a geisha's good reputation is not taken lightly.

"Geisha (Gee-sha) girls"

During the period of the Allied occupation of Japan, local women called "Geisha girls" worked as prostitutes. They almost exclusively serviced American GIs stationed in the country, who actually referred to them as "Geesha girls" (a mispronunciation).[83][84] These women dressed in kimono and imitated the look of geisha. Many Americans unfamiliar with the Japanese culture could not tell the difference between legitimate geisha and these costumed performers.[83] Shortly after their arrival in 1945, some occupying American GIs are said to have congregated in Ginza and shouted, "We want geesha girls!"[85]

Eventually, the English term "geisha girl" became a general word for any female Japanese prostitute or worker in the mizu shōbai and included bar hostesses and streetwalkers.[83]

"Geisha girls" are speculated by researchers to be largely responsible for the continuing misconception in the West that all geisha are engaged in prostitution.[83]

Mizuage

Mizuage (水揚げ) - lit., "raising the waters" - [86] was a ceremony undergone by junior kamuro and some maiko as part of the process of promotion to senior status. Originally meaning the unloading of a ship's cargo of fish, over time, the word came to represent money earned in the karyukai[7] - one of the other names for the entertainment business being the mizu shōbai, lit. "the water business".

Alongside the changing of hairstyles from the junior maiko wareshinobu style to the senior maiko ofuku style[83] and visits conducted to sister okiya and important patrons within the karyukai, some maiko would have their virginity sold to a patron who would sponsor her graduation to geisha status monetarily. This sponsorship usually constituted a relatively high cost, and so unscrupulous okiya owners would not uncommonly sell a girl's virginity more than once, ostensibly under the pretence of a patron being the girl's "first", pocketing the money entirely for themselves.

Prostitutes, particularly during the Second World War, would often use this term to refer to their acts with customers, which led to great confusion when such prostitutes called themselves "geisha" in the company of foreign soldiers, and even amongst Japanese customers.[87] Post-1956, prostitution was criminalised within Japan, and mizuage is no longer practiced within the karyukai.[88]

Appearance

A geisha's appearance will change throughout her career, from the girlish appearance of being a maiko to the more sombre appearance of a senior geisha. Different hairstyles and hairpins signify different stages of apprenticeship and training, as does the makeup - especially on maiko.

Makeup

The makeup of maiko and geisha is one of their most recognisable characteristics.

The traditional makeup of a maiko features a base of white foundation with red lipstick and red and black accents around the eyes and eyebrows. First-year maiko will only paint their lower lip with lipstick, and wear less black on the eyebrows and eyes than senior maiko. A junior maiko will paint her eyebrows shorter than a senior maiko will.[89] Maiko will also wear tonoko (a kind of blusher) on the face, usually around the eyes.[90] Young maiko often have the mother of the house or her "older sister" mentor to help apply this makeup.

The makeup of geisha does not vary much from this, though geisha will wear less tonoko than maiko. Older geisha will generally only wear full white face makeup during stage performances and special appearances. Both geisha and maiko do not colour both lips in fully, and will instead underpaint both lips, the top moreso than the bottom. The lipstick used comes in a small stick, which is melted in water.

Maiko in their final stage of training sometimes colour their teeth black for a brief period, usually when wearing the sakkō hairstyle. This practice used to be common among married women in Japan and in earlier times at the imperial court; however, it survives only in some districts. It is done partly because uncoloured teeth can appear very yellow in contrast to the oshiroi worn by maiko; from a distance, the teeth seem to disappear.

Dress

Geisha always wear kimono, though the type and the style varies based on age, occasion, region and time of year.

Apprentice geisha wear highly colourful long-sleeved kimono with extravagant and very long obi. Whereas maiko in Kyoto wear kimono with relatively large, but sparse, patterns, apprentices in places such as Tokyo wear kimono more similar in appearance to regular furisode - smaller, busier patterns.

Maiko of Kyoto wear their obi in the darari (dangling) style, whereas regional apprentices and Tokyo han-gyoku wear theirs usually tied in the fukura-suzume style, amongst others. Maiko will wear a red han-eri (collar cover) with an increasing quantity of white, gold and silver embroidery as the apprenticeship progresses.

Geisha tend to have a more uniform appearance across region, and wear kimono more subdued in pattern and colour than apprentices. Geisha always wear short-sleeved kimono, regardless of occasion or formality. Geisha wear their obi in the nijuudaiko musubi style - a taiko musubi (drum knot) tied with a fukuro obi; geisha from Tokyo and Kanazawa also wear their obi in the yanagi musubi (willow knot) style and the tsunodashi musubi style. Geisha exclusively wear solid white han-eri.

Both geisha and maiko will wear susohiki (trailing skirt) kimono to formal events, banquets and performances; some regional geisha and maiko may not wear susohiki.

Geisha wear either geta or zōri, while maiko wear either zōri or okobo - a high-heeled type of geta roughly 10-12cm tall. Both will wear tabi, whether wearing shoes or not.

Hair

The hairstyles of geisha have varied through history. In the past, it has been common for women to wear their hair down in some periods and up in others. During the 17th century, women began putting all their hair up again, and it is during this time that the traditional shimada hairstyle, a type of chignon worn by most established geisha, developed.

There are two major types of the shimada seen in the karyukai: the Taka Shimada, a high mage (high section) usually worn by young, single women and the Tsubushi Shimada, a more flattened mage generally worn by older women Additional hairstyles for maiko include Wareshinobu, Ofuku, Katsuyama, Yakko Shimada, and Sakkō. Maiko of Pontocho will wear an additional six hairstyles leading up to Sakkō, including Oshidori, Kikugasane, Yuiwata, Suisha, Oshun, and Osafune.

These hairstyles are decorated with elaborate hair-combs and hairpins (kanzashi). Beginning In the seventeenth century and continuing through the Meiji Restoration period, hair-combs were large and conspicuous, generally more ornate for higher-class women. Following the Meiji Restoration and into the modern era, smaller and less conspicuous hair-combs became more popular.

Maiko sleep with their necks on small supports (takamakura), instead of pillows, so they keep their hairstyle perfect.[42] Even if there are no accidents, a maiko will need her hair styled every week. Many modern geisha use wigs in their professional lives, while maiko use their natural hair.[91] Either must be regularly tended by highly skilled artisans. Traditional hairstyling is a slowly dying art. Over time, the hairstyle can cause balding on the top of the head.

Sakkō (先笄) is a Japanese hairstyle. It is worn by maiko today, but was worn in the Edo period by wives to show their dedication to their husbands. Maiko wear it during a ceremony called Erikae, which marks their graduation from maiko to geiko. Maiko use black wax to stain their teeth as well. Crane and tortoiseshell ornaments are added as kanzashi. The style is twisted in many knots, and is quite striking and elaborate.

In popular culture

A growing number of geisha have complained to the authorities about being pursued down the street and tugged on the sleeves of their kimono by groups of tourists keen to take their photograph. As a result, residents and local businesses have joined forces to protect the geisha by launching patrols of the streets of Kyoto's Gion entertainment district in order to prevent tourists from pestering them.[92]

Many stories are told about geisha. This includes Arthur Golden's popular English-language novel Memoirs of a Geisha which was adapted into a film in 2005.

Films about geisha

- Sisters of the Gion (1936)—Dir. Kenji Mizoguchi

- The Life of Oharu (西鶴一代女 Saikaku Ichidai Onna) (1952)—Dir. Kenji Mizoguchi

- A Geisha (祇園囃子, Gion bayashi) (1953)—Dir. Kenji Mizoguchi

- The Teahouse of the August Moon (1956)—Dir. Daniel Mann

- The Barbarian and the Geisha (1958)—Dir. John Huston

- The Geisha Boy (1958)—Dir. Frank Tashlin

- Late Chrysanthemums (Bangiku) (1958)—Dir. Mikio Naruse

- Cry for Happy (1961)—George Marshall comedy

- My Geisha (1962)—Dir. Jack Cardiff

- The Wolves (1971)—Dir. Hideo Gosha

- The World of Geisha (1973)—Dir. Tatsumi Kumashiro

- In the Realm of the Senses (1976)—Dir. Nagisa Oshima

- Ihara Saikaku Koshoku Ichidai Otoko (1991)—Dir. Yukio Abe

- The Geisha House (1999)—Dir. Kinji Fukasaku

- The Sea is Watching (2002)—Dir. Kei Kumai

- Zatoichi (2003)—Dir. Takeshi Kitano

- Fighter in the Wind (2004)—Dir. Yang Yun-ho

- Memoirs of a Geisha (2005)—Dir. Rob Marshall

- Wakeful Nights (2005)—Dir. Masahiko Tsugawa

- Maiko Haaaan!!! (2007)—Dir. Nobuo Mizuta

- Lady Maiko (2014)—Dir. Masayuki Suo

Video games about geisha

Total War: Shogun 2 (Used as agent to assassinate or seduce enemy clans)

Battle Realms (Used as healers by Dragon Clan And Serpent Clan)

See also

- Ca trù, a similar profession in Vietnam

- Hanayo

- Kanhopatra

- Kisaeng, a similar profession in Korea

- Taikomochi

- Tawaif, a similar profession in India

- Yiji, a similar profession in China

- Binukot[93], a similar profession in the Philippines

Notes

- The older system of handling a new geisha's finance was for her to loan everything from the okiya and pay it back over time. Geisha (Dalby 1983) states that "Under this system, all her wages and tips would be taken directly by the okiya until she had...[cleared] these first expenses [in 1974-5]. This process usually took about three years...[an okiya] will usually require...an outside guarantor before it will accept her [under this system]."[29]

- For geisha who handled their own finances, and did not loan anything from their okiya, for the first few years "not much would be left over [of about $600/month] after expenses were met". These numbers were calculated roughly by the then-Vice President of the Shimbashi Geisha Association, Oyumi, in Tokyo in 1974-5.[30]

References

- "How to pronounce 'Geisha'". Forvo. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "English 'geisha' translations". EZ Glot. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Masuda, Sayo (2003). Autobiography of a Geisha. Translated by Rowley, G. G. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12951-3.

- Dalby, Liza (2000). Geisha. London: Vintage Random House.

- Prasso, Sheridan (May 2006). "The Real Memoirs of Geisha". The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls, and Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-58648-394-4.

- Downer, L. (February 2004) [2003]. "In Search of Sadayakko". Madame Sadayakko The Geisha Who Bewitched the West. Gotham. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-59240-050-8.

- Gallagher, John (2003). Geisha: A Unique World of Tradition, Elegance, and Art. London: PRC. ISBN 1-85648-697-4.

- Patrick, Neil (16 May 2016). "The Rise of the Geisha - photos from 19th & 20th century show the Japanese entertainers". The Vintage News. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "History of geisha". Japan Zone. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Downer, Lesley (23 March 2006). "The City Geisha and Their Role in Modern Japan: Anomaly or artistes". In Feldman, Martha; Gordon, Bonnie (eds.). The Courtesan's Arts: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 223–242. ISBN 978-0-19-517029-0.

- Fujimoto, Taizo (1917). The Story of the Geisha Girl. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4086-9684-2.

- Seigle, C. S. (March 1993) [1931]. "Rise of the Geisha". Yoshiwara: the glittering world of the Japanese courtesan (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8248-1488-5.

- Fiorillo, J. "Osaka Prints: Glossary".

geiko: "Arts child", originally dancing girls who were too young to be called geisha but too old (more than twenty years of age) to be called odoriko. Geiko was the pronunciation used in the Kamigata region. Some geiko operated as illegal prostitutes. By the nineteenth century the term became synonymous with geisha.

- Tiefenbrun, S. (2003). "Copyright Infringement, Sex Trafficking, and the Fictional Life of a Geisha". Michigan Journal of Gender & Law. 10: 32. doi:10.2139/ssrn.460747. SSRN 460747.

- Gallagher, J. (October 2003). "Appendix II a timeline of geisha and related history". Geisha: a unique world of tradition, elegance, and art. PRC Publishing. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-85648-697-2.—Gallagher says that "Kiku" from Fukugawa district founded the profession in 1750, and that by 1753 one hundred odoriko were consigned to Yoshiwara, which licensed (female) Geisha in 1761.

- Seigle, Cecilia Segawa (1931). Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 172–174. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Dalby, Liza (1998). Geisha. Berkeley: University of California.

- Dalby, Liza. "The paradox of modernity". Geisha. p. 74. OCLC 260152400.

- Ohnuki-Tierney, E. (October 2002). Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History. University Of Chicago Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-226-62091-6.

- Dalby, Liza (2000). "11". Geisha (3rd ed.). London: Vintage Random House. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-0099286387.

[Graph titled "Geisha Ages"] Distribution of geisha according to age. In the 1920s, more than half the geisha population retired from the profession at age twenty-four or twenty-five. This trend was still evident in 1947.

- Dalby, Liza. "Do They or Don't They". lizadalby.com. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

The question always comes up...just how 'available' is a geisha? ... There is no simple answer.

- Reynolds, Wayne; Gallagher, John (2003). Geisha: A Unique World of Tradition, Elegance and Art. PRC Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 1-85648-697-4.

- "Goodby to Geisha Girl, She's on Her Way Out". The Ogden Standard-Examiner. Ogden, Utah. 27 September 1959. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Taubman, Howard (June 12, 1968). "Geisha Tradition Is Bowing Out in Japan; Geishas Fighting Losing Battle Against New Trends in Japan". The New York Times. p. 49. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- Buzzfeed Japan. "トップ芸妓が語る仕事の流儀と淡い恋 「いまから思うと好きやったんかな?」". headlines.yahoo.co.jp (in Japanese). Yahoo Japan. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Dalby—Geisha 2008 pp. 17–18.

- Geisha 2008 pp. 18, 77, 148.

- Dalby, Liza. "newgeishanotes". lizadalby.com. Liza Dalby. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

Reference 12

- Dalby, Liza (2000). Geisha (3rd ed.). London: Vintage Random House. p. 272. ISBN 0-09-928638-6.

- Dalby, Liza (2000). Geisha (3rd ed.). London: Vintage Random House. pp. 272, 273. ISBN 0-09-928638-6.

- Iwasaki, Mineko; Brown Ouchi, Rande (October 2002). Geisha: A Life (first ed.). Atria. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7434-4432-3.

- Tetsuo, I. Nihongami no sekai [The World of traditional hairstyles and hair ornaments]. Nihongami Shiryōkan. ISBN 4-9902186-1-2.

- Layton, J. "Dressing as a Geisha". howstuffworks.com.

- Melissa Hope Ditmore (2006). Encyclopedia of prostitution and sex work. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32969-9., page 184

- Reynolds, Wayne; Gallagher, John (2003). Geisha: A Unique World of Tradition, Elegance and Art. PRC Publishing. p. 159. ISBN 1-85648-697-4.

- De Mente, Boye (1966). Some Prefer Geisha. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Company.

- Mineko, Iwasaki; Brown, Rande (2003). Geisha, A Life. New York: Washington Square.

- Champeon, Kenneth (3 November 2002). "The Floating World". Things Asian. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- "What Is A Geisha?". Amino Apps. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- Dalby, Liza Crihfield (2008-12-10). Geisha. ISBN 9780520257894. OCLC 225871480.

- Rahayu, Mundi; Emelda, Lia; Aisyah, Siti (2014-11-01). "Power Relation In Memoirs Of Geisha And The Dancer". Register Journal. 7 (2): 151. doi:10.18326/rgt.v7i2.213. ISSN 2503-040X.

- McCurry, J. (11 December 2005). "Career geisha outgrow the stereotype". The Age. Melbourne. p. 3. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- Wieder, Tamara (17 October 2002). "Remaking a memoir". Boston Phoenix. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- Iwasaki, Mineko (2002). Geisha : a life. Ouchi, Rande Brown. New York: Atria Books. ISBN 0743444329. OCLC 50414454.

- Iwasaki, Mineko (2002). Geisha : a life. Ouchi, Rande Brown. New York: Atria Books. ISBN 0743444329. OCLC 50414454.

- Collins, Sarah (24 December 2007). "Japanese Feminism". Serendip Studio. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- Jones, N. (20 April 2007). "Japan's geisha hit by poor economy". The Washington Times.

now more [university] students are interested in becoming geisha

- Kalman, B. (2008). Japan the Culture. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7787-9298-7.

- McCurry, J. (11 December 2005). "Career geisha outgrow the stereotype, page 2". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- Coutsoukis, Photius (10 November 2004). "Japan Performing Arts". Retrieved 2 June 2009. Originally from The Library of Congress Country Studies; CIA World Factbook.

- Coutsoukis, Photius (10 November 2004). "Japan Dance". Retrieved 2 June 2009. Originally from The Library of Congress Country Studies; CIA World Factbook.

- Tames, Richard (September 1993). A Traveller's History of Japan. Brooklyn, New York: Interlink Books. ISBN 1-56656-138-8.

- Kalman, Bobbie (March 1989). Japan the Culture. Stevens Point, Wisconsin: Crabtree Publishing Company. ISBN 0-86505-206-9.

- Dougill, John (2006). Kyoto: a cultural history. Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-19-530137-4.

- Merriam-Webster's collegiate encyclopedia. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2000. p. 639. ISBN 0-87779-017-5.

- Lies, Elaine (23 April 2008). "Modern-day geisha triumphs in closed, traditional world". Reuters. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "World's oldest geisha looks to future to preserve past". AsiaOne. 3 December 2007. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008.

An economic downturn in the 1990s forced businessmen to cut back on entertainment expenses, while high-profile scandals in recent years have made politicians eschew excessive spending. A dinner can cost around 80,000 yen (US$1,058) per head, depending on the venue and the number of geishas present. But even before the 90s, men were steadily giving up on late-night parties at 'ryotei", restaurants with traditional straw-mat tatami rooms where geishas entertain, in favour of the modern comforts of hostess bars and karaoke rooms.

- Hyslop, Leah (4 October 2010). "Liza Dalby, the blue-eyed geisha". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Liza, Dalby (1983). Geisha. London: Vintage U.K. pp. 106–109. ISBN 9780099286387.

- Adalid, Aileen. "Up Close & Personal with Kimicho, an American Geisha in Tokyo, Japan". iamaileen. Aileen Adalid. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Gilhooly, Rob (23 July 2011). "Romanian woman thrives as geisha". The Japan Times. Tokyo. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Yaguchi, Ai. "愛知。安城の花柳界で活躍する西洋人芸妓" [Western geisha active in the flower and willow world in Anjō] (in Japanese). Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Yugawara Geiko. "「新花」の「樹里」さん" ["Juri" of "Shinka"]. Yugawara Onsen Fukiya Young Girl's Blog (in Japanese). Yugawara Onsen. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Oh, Hyun. "The Apprentice: Memoirs of a Chinese geisha wannabe in Japan". Reuters. Thomson Reuters Corporation. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- "Melbourne woman becomes a geisha". 9 News. Ninemsn Pty Ltd. 8 January 2008. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Keeping a tradition alive, from the outside in". Bangkok post. Post Publishing PCL. 25 October 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- 外国人芸者 独立はダメ 浅草の組合「想定外」 [Foreign geisha denied independence - Association talk of ‘unexpected events’]. Tokyo Shimbun (in Japanese). Japan: Tokyo Shimbun. 7 June 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "Maiko Dance". Into Japan. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- "Geisha dances". Geisha of Japan. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013.

- "Baika-sai (Plum Festival)". Kyoto Travel Guide. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "Open-Air Tea Ceremony with the Scent of Plum Blossoms: Plum Blossom Festival at Kitano Tenman-gu Shrine". Kyoto Shimbun. 25 February 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Demetriou, Danielle (16 July 2010). "Geishas serve beer instead of tea and conversation as downturn hits Japan". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Geisha beer garden opens in Kyoto". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 July 2010.

- "Geisha gardens in Kyoto". Travelbite.co.uk. 12 July 2010. Archived from the original on 12 August 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "World's oldest geisha looks to future to preserve past". 3 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

Girls in the past could become apprentice geishas from the age of 13, but it is now illegal to become an apprentice before 18 except in Kyoto where a girl can be an apprentice at 15.

- "A few [recruits] who have already become geisha are obliged to start lessons from the very beginning" (Dalby 1998, page 189)

- Jones, N. (20 April 2007). "Japan's geisha hit by poor economy". The Washington Times.

Even the older sisters who became geisha as teenagers, they are [now] over 80 but still train every day

- Maske, Andrew L. (2004). Geisha: Beyond the Painted Smile. Peabody: Peabody Essex Museum. p. 104.

- Prasso, Sheridan (April 2009). The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls, and Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient. New York: Public Affairs. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-58648-214-5.

- Henshall, K. G. (1999). A History of Japan. London: Macmillan Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-333-74940-5.

- Stanley, Amy (August 2013). "Enlightenment Geisha: The Sex Trade, Education, and Feminine Ideals in Early Meiji Japan". The Journal of Asian Studies. 72 (3): 539–562. doi:10.1017/S0021911813000570. ISSN 0021-9118.

- Matsugu, Miho (2006). "In the Service of the Nation: Geisha and Kawabata Yasunari's 'Snow Country'". In Feldman, Martha; Gordon, Bonnie (eds.). The Courtesan's Arts: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. London: Oxford University Press. p. 244. ISBN 0-19-517028-8.

- Prasso, Sheridan. "The Asian Mystique." New York: Public Affairs, 2005:206

- Ozeki, R. (2005). Inside and other short fiction: Japanese women by Japanese women. Kodansha International. ISBN 4-7700-3006-1.

- Booth, Alan (1995). Looking for the Lost: Journeys Through a Vanishing Japan. Kodansha Globe Series. ISBN 1-56836-148-3.

- Dalby, L. (February 2009). "Waters dry up". East Wind Melts the Ice: A Memoir through the Seasons by Liza Dalby. University of California Press. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-0-520-25991-1.

The resulting official line that geisha live by art alone is unrealistically prudish.

- "World War II and the American Occupation". Geisha of Japan.com.

- Dalby, Liza (2000). Geisha (3rd ed.). London: Vintage Random House. p. 115. ISBN 0099286386. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Prasso, Sheridan (2006). The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls & Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient (2nd ed.). New York: Perseus Book Group. ISBN 9780786736324.

- Tetsuo, Ishihara (2001). Nihongami no sekai - The world of traditional Japanese hairstyles. Kyoto: Nihongami Shiryōkan. pp. 66–71.

- "A Week in the Life of: Koaki, Apprentice Geisha – Schooled in the arts of pleasure". The Independent. London. 8 August 1998.

- Demetriou, Danielle (30 December 2008). "Tourists warned to stop 'harassing' Kyoto's geisha". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Santos, Mari. "'You look like the help': the disturbing link between Asian skin color and status". Splinter. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

Further reading

- Aihara, Kyoko. Geisha: A Living Tradition. London: Carlton Books, 2000. ISBN 1-85868-937-6, ISBN 1-85868-970-8.

- Ariyoshi Sawako, The Twilight Years. Translated by Mildred Tahara. New York: Kodansha America, 1987.

- Burns, Stanley B., and Elizabeth A. Burns. Geisha: A Photographic History, 1872–1912. Brooklyn, N.Y.: powerHouse Books, 2006. ISBN 1-57687-336-6.

- Downer, Lesley. Women of the Pleasure Quarters: The Secret History of the Geisha. New York: Broadway Books, 2001. ISBN 0-7679-0489-3, ISBN 0-7679-0490-7.

- Foreman, Kelly. "The Gei of Geisha. Music, Identity, and Meaning." London: Ashgate Press, 2008.

- Ishihara, Tetsuo. Peter MacIntosh, trans. Nihongami no Sekai: Maiko no Kamigata (The World of Traditional Japanese Hairstyles: Hairstyles of the Maiko). Kyoto: Dohosha Shuppan, 2004. ISBN 4-8104-1294-6.

- Iwasaki, Mineko, with Rande Brown. Geisha, A Life (also known as Geisha of Gion). New York: Atria Books, 2002. ISBN 0-7434-4432-9, ISBN 0-7567-8161-2; ISBN 0-7434-3059-X.

- Scott, A.C. The Flower and Willow World; The Story of the Geisha. New York: Orion Press, 1960.

External links

| Look up 芸者 or geisha in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Nagoya's Geiko and Maiko: Meigiren official site