Ferdinand Marcos

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos Sr. (/ˈmɑːrkɔːs/,[2] September 11, 1917 – September 28, 1989) was a Filipino politician and kleptocrat[3][4][5][6][7][8][9] who was the tenth President of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986.[10] A leading member of the New Society Movement, he ruled as a dictator[4][11][12][13] under martial law from 1972 until 1981.[14] One of the most controversial leaders of the 20th century, Marcos' rule was infamous for its corruption,[15][16][17][18] extravagance,[19][20][21] and brutality.[22][23][24]

His Excellency Ferdinand Marcos | |

|---|---|

Marcos in 1982 | |

| 10th President of the Philippines | |

| In office December 30, 1965 – February 25, 1986 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself (1978–1981) Cesar Virata (1981–1986) |

| Vice President | Fernando Lopez (1965–1972) |

| Preceded by | Diosdado Macapagal |

| Succeeded by | Corazon Aquino |

| 3rd Prime Minister of the Philippines | |

| In office June 12, 1978 – June 30, 1981 | |

| Preceded by | Office established (Position previously held by Jorge B. Vargas as Ministries involved) |

| Succeeded by | Cesar Virata |

| Secretary of National Defense | |

| In office August 28, 1971 – January 3, 1972 | |

| President | Himself |

| Preceded by | Juan Ponce Enrile |

| Succeeded by | Juan Ponce Enrile |

| In office December 31, 1965 – January 20, 1967 | |

| President | Himself |

| Preceded by | Macario Peralta |

| Succeeded by | Ernesto Mata |

| 11th President of the Senate of the Philippines | |

| In office April 5, 1963 – December 30, 1965 | |

| President | Diosdado Macapagal |

| Preceded by | Eulogio Rodriguez |

| Succeeded by | Arturo Tolentino |

| Senator of the Philippines | |

| In office December 30, 1959 – December 30, 1965 | |

| Member of the Philippine House of Representatives from Ilocos Norte's 2nd District | |

| In office December 30, 1949 – December 30, 1959 | |

| Preceded by | Pedro Albano |

| Succeeded by | Simeon M. Valdez |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos September 11, 1917 Sarrat, Ilocos Norte, Philippine Islands |

| Died | September 28, 1989 (aged 72) Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Resting place | Ferdinand E. Marcos Presidential Center, Batac, Ilocos Norte (1993–2016) Heroes' Cemetery, Taguig, Metro Manila (since November 18, 2016) |

| Political party | Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (1978–1989) |

| Other political affiliations | Liberal Party (1946–1965) Nacionalista Party (1965–1978) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | University of the Philippines |

| Profession | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | First lieutenant Major |

| Unit | 21st Infantry Division (USAFFE) 14th Infantry Regiment (USAFIP-NL) |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of the Philippines First Term

Second Term

Martial Law

Third Term

|

||

Marcos claimed an active part in World War II, including fighting alongside the Americans in the Bataan Death March and being the "most decorated war hero in the Philippines".[25] A number of his claims were found to be false[26][27][28][29][30] and United States Army documents described Marcos's wartime claims as "fraudulent" and "absurd".[31]

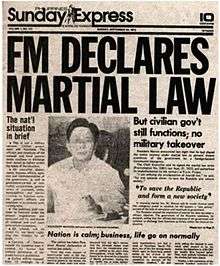

Marcos started as an attorney, then served in the Philippine House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the Philippine Senate from 1959 to 1965. He was elected President in 1965, and presided over a growing economy during the beginning and intermediate portion of his 20-year rule,[32] but ended in loss of livelihood, extreme poverty, and a crushing debt crisis.[33][34][35] Marcos placed the Philippines under martial law on September 23, 1972,[36][37][38] during which he revamped the constitution, silenced the media,[39] and used violence and oppression[24] against the political opposition,[40] Muslims, communists,[41] and ordinary citizens.[42] Martial law was ratified in 1973 through a fraudulent referendum.[43][44]

After being elected for a third term in the 1981 Philippine presidential election, Marcos's popularity suffered greatly due to public outrage of the assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr. in 1983. The assassination, along with economic collapse, revitalized the opposition, resulting in them securing a better-than-expected victory in the 1984 Philippine parliamentary election. Both of these factors alongside growing discontent and the discovery of documents exposing his finances and falsified war records, led him to call the snap election of 1986. Allegations of mass cheating, political turmoil, and human rights abuses led to the People Power Revolution of February 1986, which removed him from power.[45] To avoid what could have been a military confrontation in Manila between pro- and anti-Marcos troops, Marcos was advised by US President Ronald Reagan through Senator Paul Laxalt to "cut and cut cleanly",[46] after which Marcos fled to Hawaii.[47] Marcos was succeeded by Corazon "Cory" Aquino, widow of the assassinated opposition leader Senator Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. who had flown back to the Philippines to face Marcos.[45][48][49][50]

According to source documents provided by the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG),[51][52][53] the Marcos family stole US$5–10 billion.[54] The PCGG also maintained that the Marcos family enjoyed a decadent lifestyle, taking away billions of dollars[51][53] from the Philippines[55][56] between 1965 and 1986. His wife Imelda Marcos, whose excesses during the couple's conjugal dictatorship[57][58][59] made her infamous in her own right, spawned the term "Imeldific".[22][60][61][62] Two of their children, Imee Marcos and Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr., are still active in Philippine politics.

Early life

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos was born on September 11, 1917 in the town of Sarrat, Ilocos Norte to Mariano Marcos (1897–1945) and Josefa Edralin (1893–1988).[63]

Parents

Mariano Marcos was a lawyer and congressman from Ilocos Norte, Philippines.[64] He was killed in the waning days of World War II.[65][66]

Josefa Marcos was a schoolteacher who would far outlive her husband—dying in 1988, two years after the Marcos family left her in Malacañang Palace when they fled into exile after the 1986 People Power Revolution.[67]

Baptism

Ferdinand was baptized into the Philippine Independent Church,[68] but was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church at the age of three.

Education

Marcos studied law at the University of the Philippines in Manila, attending the College of Law. He excelled in both curricular and extra-curricular activities, becoming a valuable member of the university's swimming, boxing, and wrestling teams. He was also an accomplished and prolific orator, debater, and writer for the student newspaper. While attending the UP College of Law, he became a member of the Upsilon Sigma Phi, where he met his future colleagues in government and some of his staunchest critics.[69][70]

When he sat for the 1939 Bar Examinations, he was the bar topnotcher (top scorer), with a score of 98.8%, but allegations of cheating prompted the Philippine Supreme Court to re-calibrate his score to 92.35%.[71] He graduated cum laude. He was elected to the Pi Gamma Mu and the Phi Kappa Phi international honor societies, the latter giving him its Most Distinguished Member Award 37 years later.[72]

The murder of Julio Nalundasan

In December 1938, Ferdinand Marcos was prosecuted for the murder of Julio Nalundasan. He was not the only accused from the Marcos clan; also accused was his father, Mariano, his brother, Pio, and his brother-in-law Quirino Lizardo. Nalundasan, one of the elder Marcos's political rivals, had been shot and killed in his house in Batac on September 21, 1935 – the day after he had defeated Mariano Marcos a second time for a seat in the National Assembly.[73] According to two witnesses, the four had conspired to assassinate Nalundasan, with Ferdinand Marcos eventually pulling the trigger. In late January 1939, they were finally denied bail[74] and later in the year, they were convicted. Ferdinand and Lizardo received the death penalty for premeditated murder, while Mariano and Pio were found guilty of contempt of court. The Marcos family took their appeal to the Supreme Court of the Philippines, which overturned the lower court's decision on October 22, 1940, acquitting them of all charges except contempt.[75]

Actions during World War II

Marcos's military service during World War II has been the subject of debate and controversy, both in the Philippines and in international military circles.[76]

Marcos, who had received ROTC training, was activated for service in the US Armed Forces in the Philippines (USAFIP) after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He served as a 3rd lieutenant during the mobilization in the summer and fall of 1941, continuing until April 1942, after which he was taken prisoner.[77] According to Marcos's account, he was released from prison by the Japanese on August 4, 1942,[77] and US Military records show that he rejoined USAFIP forces in December 1944.[77] Marcos's Military service then formally ended with his discharge as a Major in the 14th Infantry, US Armed Forces in the Philippines Northern Luzon, in May 1945.[78]

Controversies regarding Marcos's military service revolve around: the reason for his release from the Japanese POW camp;[77] his actions between release from prison in August 1942 and return to the USAFIP in December 1944;[77] his supposed rank upon discharge from USAFIP;[78] and his claims to being the recipient of numerous military decorations, most of which were proven to be fraudulent.[76]

Documents uncovered by the Washington Post in 1986 suggested that Marcos's release in August 1942 happened because his father, former congressman and provincial governor Mariano Marcos, "cooperated with the Japanese military authorities" as publicist.[77]

After his release, Marcos claims that he spent much of the period between his August 1942 release and his December 1944 return to USAFIP[77] as the leader of a guerilla organization called Ang Mga Mahárlika (Tagalog, "The Freemen") in Northern Luzon.[79] According to Marcos's claim, this force had a strength of 9,000 men.[79] His account of events was later cast into doubt after a United States military investigation exposed many of his claims as either false or inaccurate.[80]

Another controversy arose in 1947, when Marcos began signing communications with the rank of Lt. Col., instead of Major.[78] This prompted US officials to note that Marcos was only "recognized as a major in the roster of the 14th Infantry USAFIP, NL as of 12 December 1944 to his date of discharge."[78]

The biggest controversy arising from Marcos's service during World War II, however, would concern his claims during the 1962 Senatorial Campaign of being "most decorated war hero of the Philippines"[76] He claimed to have been the recipient of 33 war medals and decorations, including the Distinguished Service Cross and the Medal of Honor, but researchers later found that stories about the wartime exploits of Marcos were mostly propaganda, being inaccurate or untrue.[81] Only two of the supposed 33 awards – the Gold Cross and the Distinguished Service Star – were given during the war, and both had been contested by Marcos's superiors.[81]

House of Representatives (1949–1959)

After the surrender of the Japanese and the end of World War II, the American government became preoccupied with setting up the Marshall Plan to revive the economies of the western hemisphere, and quickly backtracked from its interests in the Philippines, granting the islands independence on July 4, 1946.[82][83] Marcos ran for his father's old post as house representative of the 2nd district of Ilocos Norte and won three consecutive terms, serving in the house from 1949 to 1959.[84]

Marcos joined the "Liberal Wing" that split from the Nacionalista Party, which eventually became the Liberal Party. He eventually became the Liberal Party's spokesman on economic matters, and was made chairman of the House Neophytes Bloc which included future President Diosdado Macapagal, future Vice President Emmanuel Pelaez and future Manila Mayor Arsenio Lacson.[84]

Marcos became chairman of the House Committee on Commerce and Industry and a member of the House Committees on Defense, Ways and Means; Industry; Banks Currency; War Veterans; Civil Service; and on Corporations and Economic Planning. He was also a member of the Special Committee on Import and Price Controls and the Special Committee on Reparations, and of the House Electoral Tribunal.[84]

Philippine Senate (1959–1965)

After he served as member of the House of Representatives for three terms, Marcos won his senate seat in the elections in 1959 and became the Senate minority floor leader in 1960. He became the executive vice president of the Liberal Party in and served as the party president from 1961 to 1964.

Senate Presidency

From 1963 to 1965, he became the Senate President. Thus far, he is the last Senate President to become President of the Philippines. He introduced a number of significant bills, many of which found their way into the Republic statute books.[84]

Presidency

| Presidential styles of Ferdinand E. Marcos | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Excellency |

| Spoken style | Your Excellency |

| Alternative style | Mr. President |

Ferdinand Marcos was inaugurated to his first term as the tenth President of the Philippines on December 30, 1965, after winning the Philippine presidential election of 1965 against the incumbent President, Diosdado Macapagal. His inauguration marked the beginning of his two-decade long stay in power, even though the 1935 Philippine Constitution had set a limit of only two four-year terms of office.

Before Marcos's presidency, the Philippines was the second largest economy in Asia, behind only Japan.[85] He pursued an aggressive program of infrastructure development funded by foreign loans,[85] making him very popular throughout almost all of his first term and eventually making him the first and only President of the Third Philippine Republic to win a second term, although it would also trigger an inflationary crisis which would lead to social unrest in his second term, and would eventually lead to his declaration of martial law in 1972.[86][87]

On the evening of September 23, 1972, President Ferdinand Marcos announced that he had placed the entirety of the Philippines under martial law.[88] This marked the beginning of a 14-year period of one man rule which would effectively last until Marcos was exiled from the country on February 25, 1986. Even though the formal document proclaiming martial law - Proclamation No. 1081 - was formally lifted on January 17, 1981, Marcos retained virtually all of his powers as dictator until he was ousted by the EDSA Revolution.[88]

First term (1965–1969)

Presidential campaign

Marcos ran a populist campaign emphasizing that he was a bemedalled war hero emerging from World War II. In 1962, Marcos would claim to be the most decorated war hero of the Philippines by garnering almost every medal and decoration that the Filipino and American governments could give to a soldier.[89] Included in his claim of 27 war medals and decorations are that of the Distinguished Service Cross and the Medal of Honor.[89][90] According to Primitivo Mijares, author of the book The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos, the opposition Liberal Party would later confirm that many of his war medals were only acquired in 1962 to aid in his reelection campaign for the Senate, not for his presidential campaign.[91] Marcos won the presidency in 1965.[92]

Expansion of the Philippine Military

One of Marcos's earliest initiatives upon becoming president was to significantly expand the Philippine Military. In an unprecedented move, Marcos chose to concurrently serve as his own Defense Secretary, allowing him to have a direct hand in running the Military.[10] He also significantly increased the budget of the armed forces, tapping them in civil projects such as the construction of schools. Generals loyal to Marcos were allowed to stay in their positions past their retirement age, or were rewarded with civilian government posts, leading Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr. to accuse Marcos in 1968 of trying to establish "a garrison state."[93]

Vietnam War

Under intense pressure from the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson,[94] Marcos reversed his pre-presidency position of not sending Philippine forces to Vietnam War,[95] and consented to a limited involvement,[96] asking Congress to approve sending a combat engineer unit. Despite opposition to the new plan, the Marcos government gained Congressional approval and Philippine troops were sent from the middle of 1966 as the Philippines Civic Action Group (PHILCAG). PHILCAG reached a strength of some 1,600 troops in 1968 and between 1966 and 1970 over 10,000 Filipino soldiers served in South Vietnam, mainly being involved in civilian infrastructure projects.[97]

Loans for Infrastructure Development

With an eye towards becoming the first president of the third republic to be reelected to a second term, Marcos began taking up massive foreign loans to fund the "rice, roads, and schoolbuildings" he promised in his reelection campaign. With tax revenues unable to fund his administration's 70% increase in infrastructure spending from 1966-1970, Marcos began tapping foreign loans. creating a budget deficit 72% higher than the Philippine government's annual deficit from 1961-1965.[10]

This began a pattern of loan-funded spending which the Marcos administration would continue until the Marcoses were deposed in 1986, resulting in economic instability still being felt today, and of debts that experts say the Philippines will have to keep paying well into 2025.[10] The grandest infrastructure projects of Marcos's first term, especially the Cultural Center of the Philippines complex, also marked the beginning of what critics would call Marcos couple's Edifice complex, with grand public infrastructures projects prioritized for public funding because of their propaganda value.[98]

Jabidah expose and Muslim reactions

In March 1968 a muslim man named Jibin Arula was fished out of the waters of Manila Bay, having been shot. He was brought to then-Cavite Governor Delfin N. Montano, to whom he recounted the story of the Jabidah Massacre, saying that numerous Moro army recruits had been executed en-masse by members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) on 18 March 1968.[99] This became the subject of a senate expose by opposition Senator Benigno Aquino Jr.. [100][101]

Although the lack of living witnesses other than Arula severely hampered the probes on the incident, it became a major flashpoint that ignited the Moro insurgency in the Philippines.[102] Despite undergoing numerous trials and hearings, none of the officers implicated in the massacre were ever convicted, leading many Filipino Muslims to believe that the “Christian” government in Manila had little regard for them.[103] [104] This created a furor within the Muslim community in the Philippines, especially among the educated youth,[105] and among Muslim intellectuals, who had no discernible interest in politics prior to the incident.[102] Educated or not, the story of the Jabidah massacre led many Filipino Muslims to believe that all opportunities for integration and accommodation with the Christians were lost and further marginalised.[106]

This eventually led to the formation of the Mindanao Independence Movement in 1968, the Bangsamoro Liberation Organization (BMLO) in 1969, and the consilidation of these various forces into the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) in October 1972.[107]

1969 Presidential Campaign

Ferdinand Marcos's campaign for a second term formally began with his nomination as the presidential candidate of the Nacionalista Party at its July 1969 general meeting. A meeting of the party's ruling junta had met a week earlier to assure that the nomination would be unanimous.[108] Under the 1935 Constitution of the Philippines which was in force at the time, Marcos was supposed to be allowed a maximum of two four year terms as President.[10]

During the 1969 campaign, Marcos launched USD50 million worth in infrastructure projects in an effort to curry favor with the electorate.[109] This rapid campaign spending was so massive that it would be responsible for the Balance of Payments Crisis of 1970, whose inflationary effect would cause social unrest leading all the way up to the proclamation of Martial Law in 1972.[86][87] Marcos was reported to have spent PhP 100 for every PhP 1 that Osmena spent, using up PhP 24 Million in Cebu alone.[110]

With his popularity already beefed up by debt-funded spending, Marcos's popularity made it very likely that he would win the election, but he decided, as National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin reported in the Philippines Free Press, to "leave nothing to chance."[108] Time and Newsweek would eventually call the 1969 election the "dirtiest, most violent and most corrupt" in Philippine modern history, with the term "Three Gs", meaning "guns, goons, and gold"[111][112] coined[113] to describe administration's election tactics of vote-buying, terrorism and ballot snatching.[110]

1969 Balance of Payments Crisis

During the campaign, Marcos spent $50 million worth in debt-funded infrastructure, triggering a Balance of Payments crisis.[114] The Marcos administration ran to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help, and the IMF offered a debt restructuring deal. New policies, including a greater emphasis on exports and the relaxation of controls of the peso, were put in place. The Peso was allowed to float to a lower market value, resulting in drastic inflation, and social unrest.[115]

Second term (1969–1972)

Presidential elections were held on November 11, 1969 and Marcos was reelected for a second term. He was the first and last Filipino president to win a second full term.[116][117][118][119] His running mate, incumbent Vice President Fernando Lopez was also elected to a third full term as Vice President of the Philippines.

Social unrest after the balance of payments crisis

While Marcos had won the November 1969 election by a landslide, and was inaugurated on December 30 of that year, Marcos's massive spending during the 1969 presidential campaign had taken its toll and triggered growing public unrest.[115]

Marcos's spending during the campaign led to opposition figures such as Senator Lorenzo Tañada, Senator Jovito Salonga, and Senator Jose Diokno to accuse Marcos of wanting to stay in power even beyond the two term maximum set for the presidency by the 1935 constitution.[115]

Opposition groups quickly grew in the campuses, where students had the time and opportunity to be aware of political and economic issues.[120][121]

"Moderate" and "radical" opposition

The media reports of the time classified the various civil society groups opposing Marcos into two categories.[120][121] The "Moderates", which included church groups, civil libertarians, and nationalist politicians, were those who wanted to create change through political reforms.[120] The "radicals", including a number of labor and student groups, wanted broader, more systemic political reforms.[120][122]

The "moderate" opposition

With the Constitutional Convention occupying their attention from 1971 to 1973, statesmen and politicians opposed to the increasingly more-authoritarian administration of Ferdinand Marcos mostly focused their efforts on political efforts from within the halls of power.[10]

Their concerns varied but usually included election reform, calls for a non-partisan constitutional convention, and a call for Marcos not to exceed the two presidential terms allowed him by the 1935 Constitution.[10][122]

This notably included the National Union of Students in the Philippines,[122] the National Students League (NSL),[122] and later the Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties or MCCCL, led by Senator Jose W. Diokno.[121]

The MCCCL's rallies are particularly remembered for their diversity, attracting participants from both the moderate and radical camps; and for their scale, with the biggest one attended by as many as 50,000 people.[121]

The "radical" opposition

The other broad category of opposition groups during this period were those who wanted wanted broader, more systemic political reforms, usually as part of the National Democracy movement. These groups were branded "radicals" by the media,[120][122] although the Marcos administration extended that term to "moderate" protest groups as well.[123]

Groups considered "radical" by the media of the time included:[122]

- the Kabataang Makabayan (KM),

- the Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK),

- the Student Cultural Association of the University of the Philippines (SCAUP),

- the Movement for Democratic Philippines (MDP),

- the Student Power Assembly of the Philippines (SPAP), and

- the Malayang Pagkakaisa ng Kabataang Pilipino (MPKP).

Radicalization

When Marcos became president in 1965, Philippine policy and politics functioned under a Post-World War II geopolitical framework.[124] As a result, the Philippines was ideologically caught up in the anticommunist scare perpetuated by the US during the Cold War.[125] Marcos and the AFP thus emphasized the "threat" represented by the formation of the Communist Party of the Philippines in 1969, even if it was still a small organization.[126](p"43") partly because doing so was good for building up the AFP budget.[126](p"43")[127] As a result, notes Security Specialist Richard J. Kessler , this "mythologized the group, investing it with a revolutionary aura that on;y attracted more supporters."

The social unrest of 1969 to 1970, and the violent dispersal of the resulting "First Quarter Storm" protests were among the early watershed events in which large numbers of Filipino students of the 1970s were radicalized against the Marcos administration. Due to these dispersals, many students who had previously held “moderate” positions (i.e., calling for legislative reforms) became convinced that they had no choice but to call for more radical social change.[128][129]

Other watershed events that would later radicalize many otherwise "moderate" opposition members include the February 1971 Diliman Commune; the August 1971 suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in the wake of the Plaza Miranda bombing; the September 1972 declaration of Martial Law; the 1980 murder of Macli-ing Dulag;[130] and the August 1983 assassination of Ninoy Aquino.[122]

By 1970, study sessions on Marxism–Leninism had became common in the campuses, and many student activists were joining various organizations associated with the National Democracy Movement (ND), such as the Student Cultural Association of the University of the Philippines (SCAUP) and the Kabataang Makabayan (KM, lit. Patriotic Youth) which were founded by Jose Maria Sison;[131][132] the Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK) which was founded as a separate organization from the SCAUP and KM by a group of young writer-leaders;[133] and others.

The line between leftist activists and communists became increasingly blurred, as a significant number of radicalized activists also joined the Communist Party of the Philippines.[134] Radicalized activists from the cities began to be more extensively deployed in rural areas to prepare for People's war.[134][135]

First Quarter Storm

By the time Marcos gave the first State of the Nation Address of his second term on January 26, 1970, the unrest born from the 1969-1970 Balance of Payments Crisis exploded into a series of demonstrations, protests, and marches against the government. Student groups - some moderate and some radical - served as the driving force of the protests, which lasted until the end of the university semester in March 1970, and would come to be known as the "First Quarter Storm".[136][115]

During Marcos's January 26, 1970 State of the Nation Address, the moderate National Union of Students of the Philippines organized a protested in front of Congress, and invited student groups both moderate and radical to join them. Some of the students participating in the protest harangued Marcos as he and his wife Imelda as they left the Congress building, throwing a coffin, a stuffed alligator, and stones at them.[137]

The next major protest took place on January 30, in front of the presidential palace,[138] where activists rammed the gate with a fire truck and once the gate broke and gave way, the activists charged into the Palace grounds tossing rocks, pillboxes, Molotov cocktails. At least two activists were confirmed dead and several were injured by the police.

Five more major protests took place in the Metro Manila area took place between then and March 17, 1970 - what some media accounts would later brand the "7 deadly protests of the First Quarter Storm."[139] This included a February 12 rally at Plaza Miranda; a February 18 demonstration dubbed the "People's Congress," also supposed to be at the Plaza Miranda but dispersed early, resulting in protesters proceeding to the US Embassy where they set fire to the lobby;[129] a "Second People's Congress" demonstration on February 26; a "People's March" from Welcome Rotonda to Plaza Lawton on March 3; and the Second "People’s March" at Plaza Moriones on March 17.[139]

The protests ranged from 50,000 to 100,000 in number per weekly mass action.[134] Students had declared a week-long boycott of classes and instead met to organize protest rallies.[129]

Violent dispersals of various FQS protests were among the first watershed events in which large numbers of Filipino students of the 1970s were radicalized against the Marcos administration. Due to these dispersals, many students who had previously held “moderate” positions (i.e., calling for legislative reforms) became convinced that they had no choice but to call for more radical social change.[128]

Marcos' reactions to the protests

In Marcos's diary, he wrote that the whole crisis has been utilized by communism to create a revolutionary situation.[140][141]

He lamented that the powerful Lopez family blamed him in their newspapers for the riots thus raising the ire of demonstrators. He mentioned that he was informed by his mother of a planned assassination paid for by the powerful oligarch, Eugenio Lopez Sr. (Iñing Lopez).[140][141]

He narrated how he dissuaded his supporters from the Northern Philippines in infiltrating the demonstration in Manila and inflicting harm on the protesters, and how he showed to the UP professors that the Collegian was carrying the communist party articles and that he was disappointed in the faculty of his alma mater for becoming a spawning ground of communism. He also added that he asked Ernesto Rufino, Vicente Rufino, and Carlos Palanca to withdraw advertisements from The Manila Times which was openly supporting revolution and the communist cause, and they agreed to do so.[140][141]

Constitutional Convention of 1971

Expressing opposition to the Marcos's policies and citing rising discontent over wide inequalities in society,[10] critics of Marcos began campaigning in 1967 to initiate a constitutional convention which would revise change the 1935 Constitution of the Philippines.[142] On March 16 of that year, the Philippine Congress constituted itself into a Constituent Assembly and passed Resolution No. 2, which called for a Constitutional Convention to change the 1935 Constitution.[143]

Marcos surprised his critics by endorsing the move, but historians later noted that the resulting Constitutional Convention would lay the foundation for the legal justifications Marcos would use to extend his term past the two four-year terms allowable under the 1935 Constitution.[10]

A special election was held on November 10, 1970 to elect the delegates of the convention.[10](p"130") Once the winners had been determined, the convention was convened on June 1, 1971 at the newly completed Quezon City Hall.[144] A total of 320 delegates were elected to the convention, the most prominent being former Senators Raul Manglapus and Roseller T. Lim. Other delegates would become influential political figures, including Hilario Davide, Jr., Marcelo Fernan, Sotero Laurel, Aquilino Pimentel, Jr., Teofisto Guingona, Jr., Raul Roco, Edgardo Angara, Richard Gordon, Margarito Teves, and Federico Dela Plana.[10][145]

By 1972 the convention had already been bogged down by politicking and delays, when its credibility took a severe blow in May 1972 when a delegate exposed a bribery scheme in which delegates were paid to vote in favor of the Marcoses – with First Lady Imelda Marcos herself implicated in the alleged payola scheme.[10](p"133")[146]

The investigation on the scheme was effectively shelved when Marcos declared martial law in September 1972, and had 11 opposition delegates arrested. The remaining opposition delegates were forced to go either into exile or hiding. Within two months, an entirely new draft of the constitution was created from scratch by a special committee.[147] The 1973 constitutional plebiscite was called to ratify the new constitution, but the validity of the ratification was brought to question because Marcos replaced the method of voting through secret ballot with a system of viva voce voting by "citizen's assemblies".[148](p213) The ratification of the constitution was challenged in what came to be known as the Ratification Cases.[149][150]

Early growth of the CPP New People's Army

On December 29, 1970, Philippine Military Academy instructor Lt Victor Corpuz led New People's Army rebels in a raid on the PMA armory, capturing rifles, machine guns, grenade launchers, a bazooka and thousands of rounds of ammunition in 1970.[151] In 1972, China, which was then actively supporting and arming communist insurgencies in Asia as part of Mao Zedong's People's War Doctrine, transported 1,200 M-14 and AK-47 rifles[152] for the NPA to speed up NPA's campaign to defeat the government.[153][154]

Rumored coup d'état and assassination plot

Rumors of coup d'état were also brewing. A report of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee said that shortly after the 1969 Philippine presidential election, a group composed mostly of retired colonels and generals organized a revolutionary junta with the aim of first discrediting President Marcos and then killing him. The group was headed by Eleuterio Adevoso, an official of the opposition Liberal Party. As described in a document given to the committee by a Philippine Government official, key figures in the plot were Vice President Fernando Lopez and Sergio Osmena Jr., whom Marcos defeated in the 1969 election.[155] Marcos even went to the U.S. embassy to dispel rumors, spread by the Liberal Party, that the U.S. supported a coup d'état.[141]

While a report obtained by The New York Times speculated that rumors of a coup could be used by Marcos to justify martial law, as early as December 1969 in a message from the U.S. Ambassador to the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State, the ambassador said that most of the talk about revolution and even assassination has been coming from the defeated opposition, of which Adevoso is a leading activist. He also said that the information he has on the assassination plans are 'hard' or well-sourced and he has to make sure that it reaches President Marcos.[156][157]

In light of the crisis, Marcos wrote an entry in his diary in January 1970:[141] "I have several options. One of them is to abort the subversive plan now by the sudden arrest of the plotters. But this would not be accepted by the people. Nor could we get the Huks (Communists), their legal cadres and support. Nor the MIM (Maoist International Movement) and other subversive [or front] organizations, nor those underground. We could allow the situation to develop naturally then after massive terrorism, wanton killings and an attempt at my assassination and a coup d'etat, then declare martial law or suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus – and arrest all including the legal cadres. Right now I am inclined towards the latter."

Plaza Miranda bombing

According to interviews by The Washington Post with unnamed former Communist Party of the Philippines Officials "the (Communist) party leadership planned – and three operatives carried out – the (Plaza Miranda) attack in an attempt to provoke government repression and push the country to the brink of revolution... (Communist Party Leader) Sison had calculated that Marcos could be provoked into cracking down on his opponents, thereby driving thousands of political activists into the underground, the anonymous former officials said. Recruits were urgently needed, they said, to make use of a large influx of weapons and financial aid that China had already agreed to provide."[158] José María Sison continues to deny these claims,[159] and the CPP has never released any official confirmation of their culpability in the incident. Marcos and his allies claimed that Benigno Aquino Jr. was part of the plot, which is generally regarded as absurd given that Aquino was pro-American and pro-capitalist.[160][161]

Most historians continue to hold Marcos responsible for the Plaza Miranda bombing as he is known to have used false flag operations as a pretext for martial law.[162][163] There were a series of deadly bombings in 1971, and the CIA privately stated that Marcos was responsible for at least one of them. The agency was also almost certain that none of the bombings were perpetrated by Communists. US intelligence documents declassified in the 1990s contained further evidence implicating Marcos, provided by a CIA mole within the Philippine army.[164]

Another false flag attack took place with the attempted assassination of Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile in 1972. President Nixon approved Marcos's martial law initiative immediately afterwards.[164]

1971 Suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus

As a response to the Plaza Miranda bombing, Marcos issued Proclamation No. 889, through which he assumed emergency powers and suspended the writ of habeas corpus - an act which would later be seen as a prelude to the declaration of Martial Law more than a year later.[161]

Marcos's suspension of the writ became the event that forced many members of the moderate opposition, including figures like Edgar Jopson, to join the ranks of the radicals. In the aftermath of the bombing, Marcos lumped all of the opposition together and referred to them as communists, and many former moderates fled to the mountain encampments of the radical opposition to avoid being arrested by Marcos's forces. Those who became disenchanted with the excesses of the Marcos administration and wanted to join the opposition after 1971 often joined the ranks of the radicals, simply because they represented the only group vocally offering opposition to the Marcos government.[165][166]

1972 Manila bombings

Plaza Miranda was soon followed by a series of about twenty explosions which took place in various locations in Metro Manila in the months immediately proceeding Ferdinand Marcos's proclamation of Martial Law.[167] The first of these bombings took place on March 15, 1972, and the last took place on September 11, 1972 - twelve days before martial law was announced on September 23 of that year.

The Marcos regime officially attributed the explosions communist "urban guerillas",[167] and Marcos included them in the list of "inciting events" which served as rationalizations for his declaration of Martial Law.[168] Marcos's political opposition at the time questioned the attribution of the explosions to the communists, noting that the only suspects caught in connection to the explosions were linked to the Philippine Constabulary.[168]

The sites of the 1972 Manila bombings included the Palace Theater and Joe's Department Store on Carriedo Street, both in Manila; the offices of the Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company (PLDT), Filipinas Orient Airways, and Philippine American Life and General Insurance Company (PhilamLife); the Cubao branch of the Philippine Trust Company (now known as PhilTrust Bank); the Senate Publication Division and the Philippine Sugar Institute in Quezon City, and the South Vietnamese embassy.[167]

However, only one of these incidents - the one in the Carriedo shopping mall - went beyond damage to property; one woman was killed and about 40 persons were injured.[168]

Martial Law (1972–1981)

Proclamation No. 1081

Marcos's declaration of martial law became known to the public on September 23, 1972 when his Press Secretary, Francisco Tatad, announced through the radio[36][37][38] that Proclamation № 1081, which Marcos had supposedly signed two days earlier on September 21, had come into force and would extend Marcos's rule beyond the constitutional two-term limit.[169] Ruling by decree, he almost dissolved press freedom and other civil liberties to add propaganda machine, closed down Congress and media establishments, and ordered the arrest of opposition leaders and militant activists, including senators Benigno Aquino Jr., Jovito Salonga and Jose Diokno.[170][171] However, unlike Ninoy Aquino's Senate colleagues who were detained without charges, Ninoy, together with communist NPA leaders Lt. Corpuz and Bernabe Buscayno, was charged with murder, illegal possession of firearms and subversion.[172] Marcos claimed that martial law was the prelude to creating his Bagong Lipunan, a "New Society" based on new social and political values.

Bagong Lipunan (New Society)

Marcos had a vision of a Bagong Lipunan (New Society) similar to Indonesian president Suharto's "New Order administration", China leader Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward and Korean Kim Il-Sung's Juche. He used the years of martial law to implement this vision. According to Marcos's book Notes on the New Society, it was a movement urging the poor and the privileged to work as one for the common goals of society and to achieve the liberation of the Filipino people through self-realization.

University of the Philippines Diliman economics professor and former NEDA Director-General Dr. Gerardo Sicat,[173] an MIT Ph.D. graduate, portrayed some of Martial Law's effects as follows:[174]

Economic reforms suddenly became possible under martial law. The powerful opponents of reform were silenced and the organized opposition was also quilted. In the past, it took enormous wrangling and preliminary stage-managing of political forces before a piece of economic reform legislation could even pass through Congress. Now it was possible to have the needed changes undertaken through presidential decree. Marcos wanted to deliver major changes in an economic policy that the government had tried to propose earlier. The enormous shift in the mood of the nation showed from within the government after martial law was imposed. The testimonies of officials of private chambers of commerce and of private businessmen dictated enormous support for what was happening. At least, the objectives of the development were now being achieved...[175]

The Marcos regime instituted a mandatory youth organization, known as the Kabataang Barangay, which was led by Marcos's eldest daughter Imee. Presidential Decree 684, enacted in April 1975, required that all youths aged 15 to 18 be sent to remote rural camps and do volunteer work.[176][177]

1973 Martial Law Referendum

Martial Law was put on vote in July 1973 in the 1973 Philippine Martial Law referendum and was marred with controversy[43][44] resulting to 90.77% voting yes and 9.23% voting no.

Rolex 12 and the military

Along with Marcos, members of his Rolex 12 circle like Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile, Chief of Staff of the Philippine Constabulary Fidel Ramos, and Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines Fabian Ver were the chief administrators of martial law from 1972 to 1981, and the three remained President Marcos's closest advisers until he was ousted in 1986. Other peripheral members of the Rolex 12 included Eduardo "Danding" Cojuangco Jr. and Lucio Tan.

Between 1972 and 1976, Marcos increased the size of the Philippine military from 65,000 to 270,000 personnel, in response to the fall of South Vietnam to the communists and the growing tide of communism in South East Asia. Military officers were placed on the boards of a variety of media corporations, public utilities, development projects, and other private corporations, most of whom were highly educated and well-trained graduates of the Philippine Military Academy. At the same time, Marcos made efforts to foster the growth of a domestic weapons manufacturing industry and heavily increased military spending.[178]

Many human rights abuses were attributed to the Philippine Constabulary which was then headed by future president Fidel Ramos. The Civilian Home Defense Force, a precursor of Civilian Armed Forces Geographical Unit (CAFGU), was organized by President Marcos to battle with the communist and Islamic insurgency problem, has particularly been accused of notoriously inflicting human right violations on leftists, the NPA, Muslim insurgents, and rebels against the Marcos government.[41] However, under martial law the Marcos administration was able to reduce violent urban crime, collect unregistered firearms, and suppress communist insurgency in some areas.[179]

U.S. foreign policy and martial law under Marcos

By 1977, the armed forces had quadrupled and over 60,000 Filipinos had been arrested for political reasons. In 1981, Vice President George H. W. Bush praised Marcos for his "adherence to democratic principles and to the democratic processes".[lower-alpha 2] No American military or politician in the 1970s ever publicly questioned the authority of Marcos to help fight communism in South East Asia.

From the declaration of martial law in 1972 until 1983, the U.S. government provided $2.5 billion in bilateral military and economic aid to the Marcos regime, and about $5.5 billion through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank.[184]

In a 1979 U.S. Senate report, it was stated that U.S. officials were aware, as early as 1973, that Philippine government agents were in the United States to harass Filipino dissidents. In June 1981, two anti-Marcos labor activists were assassinated outside of a union hall in Seattle. On at least one occasion, CIA agents blocked FBI investigations of Philippine agents.[185]

Withdrawal of Taiwan relations in favor of the People's Republic of China

Prior to the Marcos administration, the Philippine government had maintained a close relationship with the Kuomintang-ruled Republic of China (ROC) government which had fled to the island of Taiwan, despite the victory of the Communist Party of China in the 1949 Chinese Communist Revolution. Prior administrations had seen the People's Republic of China (PRC) as a security threat, due to its financial and military support of Communist rebels in the country.[186]

By 1969, however, Ferdinand Marcos started publicly asserting the need for the Philippines to establish a diplomatic relationship with the People's Republic of China. In his 1969 State of the Nation Address, he said:[187]

We, in Asia must strive toward a modus vivendi with Red China. I reiterate this need, which is becoming more urgent each day. Before long, Communist China will have increased its striking power a thousand fold with a sophisticated delivery system for its nuclear weapons. We must prepare for that day. We must prepare to coexist peaceably with Communist China.

— Ferdinand Marcos, January 1969

In June 1975, President Marcos went to the PRC and signed a Joint Communiqué normalizing relations between the Philippines and China. Among other things, the Communiqué recognizes that "there is but one China and that Taiwan is an integral part of Chinese territory…" In turn, Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai also pledged that China would not intervene in the internal affairs of the Philippines nor seek to impose its policies in Asia, a move which isolated the local communist movement that China had financially and militarily supported.[188][189]

The Washington Post in an interview with former Philippine Communist Party Officials, revealed that, "they (local communist party officials) wound up languishing in China for 10 years as unwilling "guests" of the (Chinese) government, feuding bitterly among themselves and with the party leadership in the Philippines".[158]

The government subsequently captured NPA leaders Bernabe Buscayno in 1976 and Jose Maria Sison in 1977.[189]

First parliamentary elections after martial law declaration

The 1978 Philippine parliamentary election was held on April 7, 1978 for the election of the 166 (of the 208) regional representatives to the Interim Batasang Pambansa (the nation's first parliament). The elections were participated by several parties including Ninoy Aquino's newly formed party, the Lakas ng Bayan (LABAN) and the regime's party known as the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL).

The Ninoy Aquino's LABAN party fielded 21 candidates for the Metro Manila area including Ninoy himself and Alex Boncayao, who later was associated with Filipino communist death squad Alex Boncayao Brigade[190][191] that killed U.S. army Colonel James N. Rowe. All of the party's candidates, including Ninoy, lost in the election.

Marcos's KBL party won 137 seats, while Pusyon Bisaya led by Hilario Davide Jr., who later became the Minority Floor Leader, won 13 seats.

Prime Minister

In 1978, the position returned when Ferdinand Marcos became Prime Minister. Based on Article 9 of the 1973 constitution, it had broad executive powers that would be typical of modern prime ministers in other countries. The position was the official head of government, and the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. All of the previous powers of the President from the 1935 Constitution were transferred to the newly restored office of Prime Minister. The Prime Minister also acted as head of the National Economic Development Authority. Upon his re-election to the Presidency in 1981, Marcos was succeeded as Prime Minister by an American-educated leader and Wharton graduate, Cesar Virata, who was elected as an Assemblyman (Member of the Parliament) from Cavite in 1978. He is the eponym of the Cesar Virata School of Business, the business school of the University of the Philippines Diliman.

Proclamation No. 2045

After putting in force amendments to the constitution, legislative action, and securing his sweeping powers and with the Batasan, his supposed successor body to the Congress, under his control, President Marcos issued Proclamation 2045, which technically "lifted" martial law, on January 17, 1981.

However, the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus continued in the autonomous regions of Western Mindanao and Central Mindanao. The opposition dubbed the lifting of martial law as a mere "face lifting" as a precondition to the visit of Pope John Paul II.[192]

Third term (1981–1986)

We love your adherence to democratic principles and to the democratic process, and we will not leave you in isolation.

— U.S. Vice President George H. W. Bush during Ferdinand E. Marcos inauguration, June 1981[193][lower-alpha 2]

On June 16, 1981, six months after the lifting of martial law, the first presidential election in twelve years was held. President Marcos ran and won a massive victory over the other candidates.[194] The major opposition parties, the United Nationalists Democratic Organizations (UNIDO), a coalition of opposition parties and LABAN, boycotted the election.

After the lifting of martial law, the pressure on the communist CPP–NPA alleviated. The group was able to return to urban areas and form relationships with legal opposition organizations, and became increasingly successful in attacks against the government throughout the country.[189] The violence inflicted by the communists reached its peak in 1985 with 1,282 military and police deaths and 1,362 civilian deaths.[189]

Aquino's assassination

On August 21, 1983, opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr. was assassinated on the tarmac at Manila International Airport. He had returned to the Philippines after three years in exile in the United States, where he had a heart bypass operation to save his life after Marcos allowed him to leave the Philippines to seek medical care. Prior to his heart surgery, Ninoy, along with his two co-accused, NPA leaders Bernabe Buscayno (Commander Dante) and Lt. Victor Corpuz, were sentenced to death by a military commission on charges of murder, illegal possession of firearms and subversion.[172]

A few months before his assassination, Ninoy had decided to return to the Philippines after his research fellowship from Harvard University had finished. The opposition blamed Marcos directly for the assassination while others blamed the military and his wife, Imelda. Popular speculation pointed to three suspects; the first was Marcos himself through his trusted military chief Fabian Ver; the second theory pointed to his wife Imelda who had her own burning ambition now that her ailing husband seemed to be getting weaker, and the third theory was that Danding Cojuangco planned the assassination because of his own political ambitions.[195] The 1985 acquittals of Chief of Staff General Fabian Ver as well as other high-ranking military officers charged with the crime were widely seen as a whitewash and a miscarriage of justice.

On November 22, 2007, Pablo Martinez, one of the convicted suspects in the assassination of Ninoy Aquino Jr. alleged that it was Ninoy Aquino Jr.'s relative, Danding Cojuangco, cousin of his wife Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, who ordered the assassination of Ninoy Aquino Jr. while Marcos was recuperating from his kidney transplant. Martinez also alleged only he and Galman knew of the assassination, and that Galman was the actual shooter, which is not corroborated by other evidence of the case.[196]

Impeachment attempt

In August 1985, 56 Assemblymen signed a resolution calling for the impeachment of President Marcos for alleged diversion of U.S. aid for personal use,[197] citing a July 1985 San Jose Mercury News exposé of the Marcos's multimillion-dollar investment and property holdings in the United States.

The properties allegedly amassed by the First Family were the Crown Building, Lindenmere Estate, and a number of residential apartments (in New Jersey and New York), a shopping center in New York, mansions (in London, Rome and Honolulu), the Helen Knudsen Estate in Hawaii and three condominiums in San Francisco, California.

The Assembly also included in the complaint the misuse and misapplication of funds "for the construction of the Manila Film Center, where X-rated and pornographic films are exhibited, contrary to public morals and Filipino customs and traditions." The impeachment attempt gained little real traction, however, even in the light of this incendiary charge; the committee to which the impeachment resolution was referred did not recommend it, and any momentum for removing Marcos under constitutional processes soon died.

Physical decline

During his third term, Marcos's health deteriorated rapidly due to kidney ailments, as a complication of a chronic autoimmune disease lupus erythematosus. He had a kidney transplant in August 1983, and when his body rejected the first kidney transplant, he had a second transplant in November 1984.[198] Marcos's regime was sensitive to publicity of his condition; a palace physician who alleged that during one of these periods Marcos had undergone a kidney transplant was shortly afterwards found murdered. Police said he was kidnapped and slain by communist rebels.[198] Many people questioned whether he still had capacity to govern, due to his grave illness and the ballooning political unrest.[199] With Marcos ailing, his powerful wife, Imelda, emerged as the government's main public figure. Marcos dismissed speculations of his ailing health as he used to be an avid golfer and fitness buff who liked showing off his physique.

By 1984, U.S. President Ronald Reagan started distancing himself from the Marcos regime that he and previous American presidents had strongly supported even after Marcos declared martial law. The United States, which had provided hundreds of millions of dollars in aid, was crucial in buttressing Marcos's rule over the years,[200] although during the Carter administration the relationship with the U.S. had soured somewhat when President Jimmy Carter targeted the Philippines in his human rights campaign.

Cabinet

Cabinet under the Third Republic

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cabinet during the Martial Law period until 1986

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economic performance

| Population | |

|---|---|

| 1967 | 33.71 million |

| Gross Domestic Product (1985 constant prices) | |

| 1966 | |

| 1971 | |

| Growth rate, 1966–71 average | 4.75% |

| Per capita income (1985 constant prices) | |

| 1967 | |

| 1971 | |

| Total exports | |

| 1966 | |

| 1971 | |

| Exchange rates | |

| USD1 = ₱6.44 ₱1 = USD0.16 | |

| Sources:[203][204] | |

| Population | |

|---|---|

| 1985 | 54.3 million |

| Gross Domestic Product (1985 constant prices) | |

| 1972 | |

| 1985 | |

| Growth rate, 1972–85 average | 3.43% |

| Per capita income (1985 constant prices) | |

| 1972 | |

| 1985 | |

| Exchange rates | |

| USD1 = ₱20 ₱1 = USD0.05 | |

| Sources:[203][204][205] | |

The 21-year period of Philippine economic history during Ferdinand Marcos's regime—from his election in 1965 until he was ousted by the People Power Revolution in 1986—was a period of significant economic highs and lows.[206][207][208][10]

Debt

To help finance a number of economic development projects, the Marcos government borrowed large amounts of money from international lenders.[209][210] The external debt of the Philippines rose more than 70-fold from $360 million in 1962 to $26.2 billion in 1985,[211] making the Philippines one of the most indebted countries in Asia.[209] Philippine Annual Gross Domestic Product grew from $5.27 billion in 1964 to $37.14 billion in 1982, a year prior to the assassination of Ninoy Aquino. The GDP went down to $30.7 billion in 1985, after two years of economic recession brought about by political instability following Ninoy's assassination.[212] A considerable amount of this money went to the Marcos family and friends in the form of behest loans.

Reliance on US trade

As a former colony of the United States, the Philippines was heavily reliant on the American economy to purchase agricultural goods such as sugar,[213] tobacco, coconut, bananas, and pineapple[214][215] and US corporations prospered.

Economy during martial law (1973–1980)

According to World Bank Data, the Philippine's Annual Gross Domestic Product quadrupled from $8 billion in 1972 to $32.45 billion in 1980, for an inflation-adjusted average growth rate of 6% per year, while debt stood at US$17.2 billion by the end of 1980.[212][216] Indeed, according to the U.S.-based Heritage Foundation, the Philippines enjoyed its best economic development since 1945 between 1972 and 1979.[217] The economy grew amidsts two severe global oil shocks following the 1973 oil crisis and 1979 energy crisis – oil price was $3 / barrel in 1973 and $39.5 in 1979, or a growth of 1200%. By the end of 1979, debt was still manageable, with debt to Debt-GNP ratio about the same as South Korea, according to the US National Bureau of Economic Research.[216]

Foreign capital was invited to invest in certain industrial projects. They were offered incentives, including tax exemption privileges and the privilege of bringing out their profits in foreign currencies. One of the most important economic programs in the 1980s was the Kilusang Kabuhayan at Kaunlaran (Movement for Livelihood and Progress). This program was started in September 1981. It aimed to promote the economic development of the barangays by encouraging its residents to engage in their own livelihood projects. The government's efforts resulted in the increase of the nation's economic growth rate to an average of six percent or seven percent from 1970 to 1980.[218]

Economy after martial law (1981–1985)

The Philippine economy, heavily reliant on exports to the United States, suffered a great decline after the Aquino assassination in August 1983 because Filipino business and political leaders who studied in Harvard, Yale, and other US universities began lobbying American and foreign firms to discourage them from investing in the Philippines. This was taking place at the same time that China was beginning to accept free-market capitalism and American businesses were jockeying to establish manufacturing plants in China. The political troubles of the Philippines hindered the entry of foreign investments, and foreign banks stopped granting loans to the Philippine government.

In an attempt to launch a national economic recovery program and despite his growing isolation from American businesses, Marcos negotiated with foreign creditors including the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for a restructuring of the country's foreign debts – to give the Philippines more time to pay the loans. Marcos ordered a cut in government expenditures and used a portion of the savings to finance the Sariling Sikap (Self-Reliance), a livelihood program he established in 1984.

However, the economy continued to shrink despite the government's recovery efforts due to a number of reasons. Most of the so-called government development programs failed to materialize. Government funds were often siphoned off by Marcos or his cronies. American investors were discouraged by the Filipino economic elite who were against the corruption that by now had become endemic in the Marcos regime.[219] The failure of the recovery program was further augmented by civil unrest, rampant graft and corruption within the government, and Marcos's lack of credibility. The unemployment rate increased from 6.25% in 1972 to 11.058% in 1985.[220]

Considering the severe 1984–1985 recession, the Philippine economy annual growth rate from 1972 to 1985 of 3.4% is significantly lower than the 5.4% growth rate achieved by other countries in ASEAN (Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore) in the same time period.[34]

Creation of the Credit Information Bureau

In 1981, Ferdinand Marcos issued Letter of Instructions No. 1107 mandating the Central Bank of the Philippines to analyze the probability of establishing and funding the operation of a credit bureau in the Philippines due to the disturbing increase of failures on corporate borrowers.[221] In adherence to the order, Central Bank of the Philippines organized the Credit Information Exchange System under the department of Loans and Credit. It was created to engage in collating, developing and analyzing credit information on individuals, institutions, business entities and other business concerns. It aims to develop and undertake the continuing exchange of credit data within its members and subscribers and to provide an impartial source of credit information for debtors, creditors and the public. On April 14, 1982, Credit Information Bureau, Inc. was incorporated as a non-stock, non-profit corporation. CIBI was created pursuant to LOI No. 1107 dated February 16, 1981 and was further strengthened by PD No. 1941 which recognizes and supports CIBI as a suitable credit bureau to promote the development and maintenance of rational and efficient credit processes in the financial system and in the economy as a whole. In 1997, Credit Information Bureau, Inc. was incorporated and transformed into a private entity and became CIBI Information, Inc. CIBI is a provider of information and intelligence for business, credit and individuals.[222] The company also supplies compliance reports before accrediting suppliers, industry partners and even hiring professionals.[223]

Economic controversies

According to the book The Making of the Philippines by Frank Senauth (p. 103):[224]

Marcos himself diverted large sums of government money to his party's campaign funds. Between 1972 and 1980, the average monthly income of wage workers had fallen by 20%. By 1981, the wealthiest 10% of the population was receiving twice as much income as the bottom 60%.[225]

The country's total external debt rose from US$2.3 billion in 1970 to US$26.2 billion in 1985 during Marcos's term. Marcos's critics charged that policies have become debt-driven with rampant corruption and plunder of public funds by Marcos and his cronies. This held the country under a debt-servicing crisis which is expected to be fixed by only 2025. Critics have pointed out an elusive state of the country's development as the period is marred by a sharp devaluing of the Philippine Peso from 3.9 to 20.53. The overall economy experienced a slower growth GDP per capita, lower wage conditions and higher unemployment especially towards the end of Marcos's term after the 1983–1984 recession. Some of Marcos's critics claimed that poverty incidence grew from 41% in the 1960s at the time Marcos took the Presidency to 59% when he was removed from power,[226][227][216][228][229][230]

From 1972 to 1980, agricultural production fell by 30%. After declaring martial law in 1972, Marcos promised to implement agrarian reforms. However, the land reforms served largely to undermine Marcos's landholder opponents, not to lessen inequality in the countryside,[231] and encouraged conversion to cash tenancy and greater reliance on farm workers.[232] Under Marcos, timber products were among the nation's top exports but little attention was paid to the environmental impacts of deforestation as cronies never complied with reforestation agreements. By the early 1980s, forestry collapsed because most of the Philippines' accessible forests had been depleted—of the 12 million hectares of forestland, about 7 million had been left barren."[233][234]

While the book claimed that agricultural production declined by 30% in the 1970s and suggested that timber exports were growing in the same period, an article published by the World Bank on Philippine Agriculture says that crops (rice, corn, coconut, sugar), livestock and poultry and fisheries grew at an average rate of 6.8%, 3% and 4.5%, respectively from 1970 to 1980, and the forestry sector actually declined by an annual average rate of 4.4% through the 1970s.[235]

Despite claims made by the book that land reforms served largely to undermine Marcos's landholder opponents, Marcos's government did not distribute to small farmers his political rival Ninoy Aquino's family's 6,453 hectare Hacienda Luisita plantation, the biggest in the country.[236][237]

By 1960 the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations had worked with the Garcia administration and the UP College of Agriculture to establish the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Los Baños, Laguna,[238](p7) signaling the rise of the Green Revolution (industrialized, chemical agriculture) to the Philippines.[239] In the late '60s, the Marcos administration took advantage of IRRI's new "miracle rice" cultivar (IR8),[239] promoting its use throughout the Philippines. While this resulted in annual rice production in the Philippines increasing from 3.7 to 7.7 million tons in two decades and made the Philippines a rice exporter for the first time in the 20th century,[240][241] the switch to IR8 required more fertilizers and pesticides. This and other related reforms resulted in high profits for transnational corporations, but were generally harmful to small, peasant farmers who were often pushed into poverty.[242]

Snap election, revolution

In late 1985, in the face of escalating public discontent and under pressure from foreign allies, Marcos called a snap election with more than a year left in his term. He selected Arturo Tolentino as his running mate. The opposition to Marcos united behind two American-educated leaders, Aquino's widow, Corazon, and her running mate, Salvador Laurel.[243][244]

It was during this time that Marcos's World War II medals for fighting the Japanese Occupation was first questioned by the foreign press. During a campaign in Manila's Tondo district, Marcos retorted:[245]

You who are here in Tondo and fought under me and who were part of my guerrilla organization—you answer them, these crazy individuals, especially the foreign press. Our opponents say Marcos was not a real guerrilla. Look at them. These people who were collaborating with the enemy when we were fighting the enemy. Now they have the nerve to question my war record. I will not pay any attention to their accusation.

— Ferdinand Marcos, January 1986

Marcos was referring to both presidential candidate Corazon Aquino's father-in-law Benigno Aquino Sr. and vice presidential candidate Salvador Laurel's father, José P. Laurel, who were leaders of the KALIBAPI, a puppet political party that collaborated with the Japanese during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Both were arrested and charged for treason after the war.[246]

The elections were held on February 7, 1986.[247] The official election canvasser, the Commission on Elections (COMELEC), declared Marcos the winner. The final tally of the COMELEC had Marcos winning with 10,807,197 votes against Aquino's 9,291,761 votes. On the other hand, the partial 69% tally of the National Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL), an accredited poll watcher, had Aquino winning with 7,502,601 votes against Marcos's 6,787,556 votes. Cheating was reported on both sides.[248] This electoral exercise was marred by widespread reports of violence and tampering of election results.

Despite common knowledge that Marcos cheated the elections, some claim that Marcos is the one that had been cheated by NAMFREL because his Solid North votes were transmitted very late to the tabulation center at the PICC. Two NAMFREL volunteers were hanged in Ilocos. The Ilocano votes were enough to overwhelm Cory's lead in Metro Manila and other places.[249]

The alleged fraud culminated in the walkout of 35 COMELEC computer technicians to protest the manipulation of the official election results to favor Ferdinand Marcos. The walkout of computer technicians was led by Linda Kapunan[250] and the technicians were protected by Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) officers led by her husband Lt. Col. Eduardo "Red" Kapunan. RAM, led by Lt. Col. Gregorio "Gringo" Honasan and backed by Enrile had plotted a coup d'etat to seize Malacañang and kill Marcos and his family.[251]

The failed election process gave a decisive boost to the "People Power movement." Enrile and Ramos would later abandon Marcos's 'sinking ship' and seek protection behind the 1986 People Power Revolution, backed by fellow-American educated Eugenio Lopez Jr., Jaime Augusto Zobel de Ayala, and the old political and economic elites. At the height of the revolution, Juan Ponce Enrile revealed that a purported and well-publicized ambush attempt against him years earlier was in fact faked, in order for Marcos to have a pretext for imposing martial law. However, Marcos never ceased to maintain that he was the duly elected and proclaimed president of the Philippines for a fourth term, but unfairly and illegally deprived of his right to serve it. On February 25, 1986, rival presidential inaugurations were held,[252] but as Aquino supporters overran parts of Manila and seized state broadcaster PTV-4, Marcos was forced to flee.[253]

Exile in Hawaii

Fleeing from the Philippines to Hawaii

At 15:00 PST (GMT+8) on February 25, 1986, Marcos talked to United States Senator Paul Laxalt, a close associate of the United States President, Ronald Reagan, asking for advice from the White House. Laxalt advised him to "cut and cut cleanly", to which Marcos expressed his disappointment after a short pause.[254] In the afternoon, Marcos talked to Enrile, asking for safe passage for him and his family, and included his close allies like General Ver. Finally, at 9:00 p.m., the Marcos family was transported by four Sikorsky HH-3E helicopters[255] to Clark Air Base in Angeles City, Pampanga, about 83 kilometers north of Manila, before boarding US Air Force C-130 planes bound for Andersen Air Force Base in Guam, and finally to Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii where Marcos arrived on February 26.

As per the official 23-page US Customs record, the two C-141 transport planes that carried the Marcos family and their closest allies had 23 wooden crates; 12 suitcases and bags, and various boxes, whose contents included enough clothes to fill 67 racks; 413 pieces of jewelry; 24 gold bricks, inscribed "To my husband on our 24th anniversary"; and more than 27m Philippine pesos in freshly printed notes. The jewelry included 70 pairs of jewel-studded cufflinks; an ivory statue of the infant Jesus with a silver mantle and a diamond necklace. The total value of these items was $15 millon.[256] Meanwhile, when protestors stormed Malacañang Palace shortly after their departure, it was famously discovered that Imelda had left behind over 2,700 pairs of shoes in her closet.[257]

The Catholic hierarchy and Manila's middle class were crucial to the success of the massive crusade, but only within Metro Manila because no mass demonstrations or protests against Marcos occurred in the provinces and islands of Visayas and Mindanao.

Plans to return to the Philippines and 'The Marcos Tapes'

More than a year after the People Power Revolution, it was revealed to the United States House Foreign Affairs subcommittee in 1987 that Marcos held an intention to fly back to the Philippines and overthrow the Aquino government. Two Americans, namely attorney Richard Hirschfeld and business consultant Robert Chastain, both of whom posed as arms dealers, gained knowledge of a plot by gaining Marcos's trust and secretly tape recorded their conversations with the ousted leader.

According to Hirschfeld, he was first invited by Marcos to a party held at the latter's family residence in Oahu, Hawaii. After hearing that one of Hirschfeld's clients was Saudi Sheikh Mohammad Fassi, Marcos's interest was piqued because he had done business with Saudis in the past. A few weeks later, Marcos asked for help with securing a passport from another country, in order to travel back to the Philippines while bypassing travel restrictions imposed by the Philippines and United States governments. This failed, however, and subsequently Marcos asked Hirschfeld to arrange a $10-million loan from Fassi.

On January 12, 1987, Marcos stated to Hirschfeld that he required another $5-million loan "in order to pay 10,000 soldiers $500 each as a form of 'combat life insurance.' When asked by Hirschfeld if he was talking about an invasion of the Philippines, Marcos responded, "Yes." Hirschfeld also recalled that the former president said that he was negotiating with several arms dealers to purchase up to $18 million worth of weapons, including tanks and heat-seeking missiles, and enough ammunition to "last an army three months."

Marcos had thought of being flown to his hometown in Ilocos Norte, greeted by his loyal supporters, and initiating a plot to kidnap Corazon Aquino. ″What I would like to see happen is we take her hostage,″ Marcos told Chastain. ″Not to hurt her ... no reason to hurt her .. to take her.″

Learning of this plan, Hirschfeld contacted the US Department of Justice, and was asked for further evidence. This information eventually reached President Ronald Reagan, who placed Marcos under "island arrest", further limiting his movement.[258][259]

In response, the Aquino government dismissed Marcos's statements as being a mere propaganda ploy.[260]

Corruption in the Marcos Era

Monopolies

Marcos’ administration spawned new oligarchs in Philippine society who became instant millionaires. These oligarchs plundered government financing institutions to finance their corporate raiding, monopolies and various takeover schemes. Marcos’ cronies were awarded timber, mining and oil concessions and vast tracts of rich government agricultural and urban lands, not to mention lush government construction contracts. During his martial law regime, Marcos confiscated and appropriated by force and duress many businesses and institutions, both private and public, and redistributed them to his cronies and close personal friends. A presidential crony representing Westington won for its principal the $500 million bid for the construction of the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant in Bagac. The crony's commission was $25 million or $200 million representing five percent of the total bid price. These new oligarchs were known to be insatiable and more profligate than the oligarchs of pre-martial law days.[123] Two of Marcos's friends were Eduardo "Danding" Cojuangco Jr., who would go on to control San Miguel Corporation, and Ramon Cojuangco, late businessman and chairman of PLDT, and father of Antonio "Tony Boy" Cojuangco (who would eventually succeed his father in the telecommunications company), both happened to be cousins of Corazon Aquino. These associates of Marcos then used these as fronts to launder proceeds from institutionalized graft and corruption in the different national governmental agencies as "crony capitalism" for personal benefit. Graft and corruption via bribery, racketeering, and embezzlement became more prevalent during this era. Marcos also silenced the free press, making the press of the state propaganda the only legal one, which was a common practice for governments around the world that sought to fight communism.