European perch

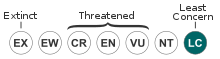

Perca fluviatilis, commonly known as the common perch, European perch, redfin perch, big-scaled redfin, English perch, Eurasian perch, Eurasian river perch or in Anglophone parts of Europe, simply the perch, is a predatory species of the freshwater perch native to Europe and northern Asia. The species is a popular quarry for anglers, and has been widely introduced beyond its native area, into Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. They have caused substantial damage to native fish populations in Australia and have been proclaimed a noxious species in New South Wales.[1]

| European perch | |

|---|---|

| |

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Percidae |

| Genus: | Perca |

| Species: | P. fluviatilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Perca fluviatilis | |

| |

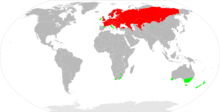

| Red: native range Green: introduced range | |

Description

European perch are greenish with red pelvic, anal and caudal fins. They have five to eight dark vertical bars on their sides.[2][3] When the perch grow larger, a hump grows between its head and dorsal fin.[4]

European perch can vary greatly in size between bodies of water. They can live for up to 22 years, and older perch are often much larger than average; the maximum recorded length is 60 cm (24 in). The British record is 2.8 kg (6 lb 2 oz), but they grow larger in mainland Europe than in Britain. As of May 2016, the official all tackle world record recognised by the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) stands at 2.9 kg (6 lb 6 oz) for a Finnish fish caught September 4, 2010.[5] In January 2010 a perch with a weight of 3.75 kg (8 lb 4 oz) was caught in the River Meuse, Netherlands.[6] Due to the low salinity levels of the Baltic Sea, especially around the Finnish archipelago and Bothnian Sea, many freshwater fish live and thrive there. Perch especially are in abundance and grow to a considerable size due to the diet of Baltic herring.

Distribution and habitat

The range of the European perch covers fresh water basins all over Europe, excluding the Iberian peninsula. Their range is known to reach the Kolyma River in Siberia to the east.[3] It is also common in some of the brackish waters of the Baltic Sea.[7]

European perch has been widely introduced, with reported adverse ecological impact after introduction.[3]

The European perch lives in slow-flowing rivers, deep lakes and ponds. It tends to avoid cold or fast-flowing waters but some specimens penetrate waters of these type, although they do not breed in this habitat.[7]

Behaviour and reproduction

The perch is a predatory species. Juveniles feed on zooplankton, bottom invertebrate fauna and other perch fry, while adults feed on both invertebrates and fish, mainly sticklebacks, perch, roach and minnows.[7] Perch start eating other fish when they reach a size of around 120 mm.[8]

Male perch become sexually mature at between one and two years of age, females between two and four.[8] In the northern hemisphere they spawn between February and July,[7] depositing their eggs on water plants or the branches of trees or shrubs immersed in the water.[3] There has been speculation, but only anecdotal evidence, that eggs stick to the legs of wading birds and are then transferred to other waters.[9]

Taxonomy

The first scientific description of the river perch was made by Peter Artedi in 1730. He defined the basic morphological signs of this species after studying perch from Swedish lakes. Artedi described its features, counting the fin rays scales and vertebrae of the typical perch.

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus named it Perca fluviatilis.[10] His description was based on Artedi's research.

Because of their similar appearance and ability to cross-breed, the yellow perch (Perca flavescens) has sometimes been classified as a subspecies of the European perch, in which case its trinomial name would be Perca fluviatilis flavescens.[11]

Fishing

_fingerlings_for_quality_control_at_Valperca.jpg)

European perch is fished for food and game fishing.[7]

According to FAO statistics 28,920 tonnes were caught in 2013. Largest perch fishing countries were Russia, (15,242 tonnes), Finland (7,666 tonnes), Estonia (2,144 t), Poland (1,121 t) and Kazakhstan (1,103 t).[7]

Baits for perch include minnows, goldfish, weather loaches, pieces of raw squid or pieces of raw fish (mackerel, bluey, jack mackerel, sardine), or brandling, red, marsh, and lob worms, maggots, shrimp (Caridina, Neocaridina, Palaemon, Macrobrachium) and peeled crayfish tails. The tackle needed is fine but strong. Artificial lures are also effective, particularly for medium-sized perch.

It is possible to fly fish for perch using artificial flies tied for the purpose. Often, the flies required are "streamers" or bait-fish imitations and use flash, colour and movement to entice a take from the perch.[12]

Predators

The European perch is a frequent prey of many fish-eating predators, such as the great cormorant[13][14] and common kingfisher.[15][16]

Diseases and parasites

Cucullanus elegans is a species of parasitic nematode. It is an endoparasite of the European perch.[17] Juvenile perch are commonly infected by Camallanus lacustris (Nematoda), Proteocephalus percae, Bothriocephalus claviceps, Glanitaenia osculata, Triaenophorus nodulosus (all Cestoda) and Acanthocephalus lucii (Acanthocephala)[18]

Perch in culture

The European perch is Finland’s national fish.[19]

It is also pictured in emblems of several European towns and municipalities, such as Bad Buchau, Gröningen and Schönberg, Plön.

References

- "Redfin perch". NSW Government. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Perch (Perca fluviatilis)". ARKive. Wildscreen. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Perca fluviatilis Linnaeus, 1758". FishBase. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- "Perch". Luontoportti. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Official World Record". The International Game Fish Association. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Fischdaten". Fisch-Hitparade (in German). 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Species Fact Sheet (incl. link to FishStat)". FAO. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- J. Freyhof & M. Kottelat (2008). "Perca fluviatilis". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T16580A6135168. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T16580A6135168.en.

- "Is there (scientific) proof that water fowl can transport fish eggs from one water body to an other?". ResearchGate. 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Synonyms of Perca fluviatilis Linnaeus, 1758". FishBase. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- Bailly, N (2015). "Perca fluviatilis flavescens (Mitchill, 1814) – unaccepted". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- "Perch On The Fly". Fishtec. 2016-11-28. Retrieved 2018-11-12.

- Čech, M., Čech, P., Kubečka, J., Prchalová, M., Draštík, V (2008). "Size selectivity in summer and winter diets of great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo): Does it reflect season-dependent difference in foraging efficiency?". Waterbirds. 31 (3): 438–447. doi:10.1675/1524-4695-31.3.438. JSTOR 25148353.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Čech M., Vejřík, L. (2011). "Winter diet of great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) on the River Vltava: estimate of size and species composition and potential for fish stock losses". Folia Zoologica. 60 (2): 129–142. doi:10.25225/fozo.v60.i2.a7.2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Čech M., Čech P. (2015). "Non-fish prey in the diet of an exclusive fish-eater: the Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis". Bird Study. 62 (4): 457–465. doi:10.1080/00063657.2015.1073679.

- Čech M., Čech P (2017). "Effect of brood size on food provisioning rate in Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis". Ardea. 105 (1): 5–17. doi:10.5253/arde.v105i1.a3.

- "Cucullanus elegans Rudolphi, 1802". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Kuchta, R., Čech, M., Scholz, T., Soldánová, M., Levron, C., Škoríková, B. (2009). "Endoparasites of European perch Perca fluviatilis fry: role of spatial segregation". Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 86: 87–91. doi:10.3354/dao02090.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Weaver, Fran (2014). "Iconic Finnish nature symbols stand out". thisisFinland. Finland Promotion Board. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Perca fluviatilis. |