Eurasian beaver

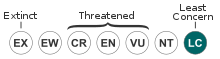

The Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) or European beaver is a beaver species that was once widespread in Eurasia, but was hunted to near-extinction for both its fur and castoreum. At the turn of the 20th century, only about 1,200 beavers survived in eight relict populations in Europe and Asia.[2] It has been reintroduced to much of its former range, and now occurs from Spain, Central Europe, Great Britain and Scandinavia to a few regions in China and Mongolia.[3] It is listed as least concern on the IUCN Red List, as it recovered well in most of Europe. It is extinct in Portugal, Moldova, and Turkey.[1]

| Eurasian beaver | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Castoridae |

| Genus: | Castor |

| Species: | C. fiber |

| Binomial name | |

| Castor fiber | |

| Approximate current range of the Eurasian beaver | |

Characteristics

The Eurasian beaver's fur colour varies between regions. Light, chestnut-rust is the dominant colour in Belarus. In Russia's Sozh River basin, it is predominantly blackish brown, while in the Voronezh Reserve beavers are both brown and blackish-brown.[3]

The Eurasian beaver is one of the largest living rodent species and the largest rodent native to Eurasia. Its head-to-body length is 80–100 cm (31–39 in) with a 25–50 cm (9.8–19.7 in) long tail length. It weighs around 11–30 kg (24–66 lb).[3] In Norway, adult males average 21.5 kg (47 lb), while females average 23.1 kg (51 lb). Adults from the same country average 18.4 kg (41 lb). By the average weights known, it appears to be the world's second heaviest rodent after the capybara, and is slightly larger and heavier than the North American beaver.[4][5][6] The largest recorded specimen weighed 31.7 kg (70 lb), but it can exceptionally exceed 40 kg (88 lb).[7]

Differences from North American beaver

Although the Eurasian beaver appears superficially similar to the North American beaver, there are several important differences, chief among these being that the North American beaver has 40 chromosomes, while the Eurasian beaver has 48. The two species are not genetically compatible: After more than 27 attempts in Russia to hybridise the two species, the result was one stillborn kit that was bred from the pairing of a male North American beaver and a female Eurasian beaver. The difference in chromosome count makes interspecific breeding unlikely in areas where the two species' ranges overlap.[3]

Fur

The guard hairs of the Eurasian beaver have longer hollow medullae at their tips. There is also a difference in the frequency of fur colours: 66% of Eurasian beavers overall have beige or pale brown fur, 20% have reddish brown, nearly 8% are brown, and only 4% have blackish coats; among North American beavers, 50% have pale brown fur, 25% are reddish brown, 20% are brown, and 6% are blackish.[3]

Head

The Eurasian beaver has a larger, less rounded head; a longer, narrower muzzle. The Eurasian beaver also has longer nasal bones, with the widest point being at the end of the snout; in the case of the North American beaver, the widest point is at the middle of the snout. The Eurasian beaver has a triangular nasal opening, unlike those of the North American beavers, which are square. Furthermore, the foramen magnum is rounded in the Eurasian beaver, but triangular in the North American beaver.

Body

The Eurasian beaver has a narrower, less oval-shaped tail; and shorter shin bones, making it less capable of bipedal locomotion than the North American species. The anal glands of the Eurasian beaver are larger, and thin-walled, with a large internal volume, relative to that of the North American beaver.

Taxonomy

Castor fiber was the scientific name used by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, who described the beaver in his work Systema Naturae.[8] Between 1792 and 1997, several Eurasian beaver zoological specimens were described and proposed as subspecies, including:[9]

- C. f. albus and C. f. solitarius by Robert Kerr in 1792[10]

- C. f. fulvus and C. f. variegatus by Johann Matthäus Bechstein in 1801[11]

- C. f. galliae by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in 1803

- C. f. flavus, C. f. varius and C. f. niger by Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest in 1822

- C. f. gallicus Johann Baptist Fischer in 1829

- C. f. proprius by Gustaf Johan Billberg in 1833

- C. f. albicus, C. f. balticus and C. f. vistulanus by Paul Matschie in 1907

- C. f. birulai and C. f. pohlei by Serebrennikov in 1929

- C. f. tuvinicus by Lavrov in 1969[12]

- C. f. belarusicus and C. f. osteuropaeus by Lavrov in 1974

- C. f. belorussicus and C. f. orientoeuropaeus by Lavrov in 1981[12]

- C. f. bielorussieus by Lavrov in 1983

- C. f. introductus by Saveljev in 1997

These descriptions were largely based on very small differences in fur colour and cranial morphology, none of which warrant a subspecific distinction.[13] In 2005, analysis of mitochondrial DNA of Eurasian beaver samples showed that only two evolutionarily significant units exist: a western phylogroup in Western and Central Europe, and an eastern phylogroup in the region east of the Oder and Vistula rivers.[14] The eastern phylogroup is genetically more diverse, but still at a degree below thresholds considered sufficient for subspecific differentiation.[15]

Distribution and habitat

The Eurasian beaver is recovering from near extinction, after depredation by humans for its fur and for castoreum, a secretion of its scent gland believed to have medicinal properties.[16] The estimated population was only 1,200 by the early 20th century.[2][17] In many European nations, the Eurasian beaver became extinct, but reintroduction and protection programmes led to gradual recovery so that by 2003, the population comprised about 639,000 individuals.[18] It likely survived east of the Ural Mountains from a 19th-century population as low as 300 animals. Factors contributing to their survival include their ability to maintain sufficient genetic diversity to recover from a population as low as three individuals, and that beavers are monogamous and select mates that are genetically different from themselves.[19][20] About 83% of Eurasian beavers live in the former Soviet Union due to reintroductions.[15]

Continental Europe

In Spain, nongovernment sanctioned reintroduction around 2003 has resulted in tell-tale beaver signs documented on a 60-km stretch on the lower course of the Aragon River and the area adjoining the Ebro River in Aragon, Spain.[21]

In France, the Eurasian beaver was almost extirpated by the late 19th century, with only a small population of about 100 individuals surviving in the lower Rhône valley. Following protection measures in 1968 and 26 reintroduction projects, it re-colonized the Rhône river and other river systems in the country such as Loire, Saône, Moselle, Tarn and Seine rivers. In 2011, the French beaver population was estimated at 14,000 individuals living along 10,500 km (6,500 mi) watercourses.[22]

In Germany, around 200 Eurasian beavers survived by the end of the 19th century in the Elbe river system in Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg.[23] By 2016, beavers numbered up to 25,000 across Germany, even appearing in many urban areas. The largest beaver population lives in eastern Germany with about 6,000 individuals descended from Elbe beavers, and in Bavaria along the Danube and its tributaries. After a resettlement programme started in 1966, around 14,000 individuals are estimated in Bavaria.[24]

In Switzerland, the Eurasian beaver was extirpated in the early 19th century due to hunting for its fur, meat and castoreum. Between 1956 and 1977, 141 individuals were reintroduced to 30 sites in the Rhone and Rhine catchment areas. They originated in France, Russia and Norway.[25]

Beavers were reintroduced in the Netherlands in 1988 after being completely exterminated in the 19th century. After its reintroduction in the Biesbosch, the Dutch population has spread considerably (supported by additional reintroductions), and can now be found in the Biesbosch and surrounding areas, along the Meuse in Limburg, and in the Gelderse Poort and Oostvaardersplassen. In 2012, the population was estimated to be about 600 animals and could easily grow to 7000 in 20 years' time. According to the Mammal Society and the Dutch Water Board, this will cause a threat to the river dikes. The main problem is that beavers excavate corridors and caves in dikes, thereby undermining the stability of the dike, just as the muskrat and the coypu do.[26] If problems become unmanageable, as local administrators in Limburg fear, the beaver will be captured again.[27]

As of 2014, the beaver population in Poland reached 100,000 individuals.[28] and was still growing. After major flooding in Poland in May and June 2010, the local authorities of Konin in central Poland held beavers responsible for causing the flooding and demanded the culling of 150 beavers.[29]

In Romania, beavers became extinct in 1824, but were reintroduced in 1998 along the Olt River, spreading to other rivers in Covasna County.[30] In 2014, the animals were confirmed to have reached the Danube Delta.[31]

In the former Soviet Union, almost 17,000 beavers were translocated from 1927 to 2004, of which 12,000 were to Russia, and the remainder to the Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic States, and Kazakhstan.[2] The beaver is now common in Estonia and Latvia.

The recently resurgent beaver population in Eurasia has resulted in increases in human-beaver encounters. Indeed, in May 2013, a Belarusian fisherman died after being bitten several times by a beaver, severing an artery in his leg and causing him to bleed to death.[32]

In Greece, the Eurasian beaver was first described by Aristotle in the 4th century BCE under the name Λάταξ/Latax. He wrote that it is wider than the otter, with strong teeth and that it gets often in the night to the river banks to cut down trees with these teeth.[33] Remains from late Roman, early Byzantine periods and from the late 18th, early 19th century, have been found in Nicopolis.[34] Ιt remains unclear when they vanished from Kastoria which was possibly named after Kastor/Castor which means beaver, but in 18th century CE the locals were still hunting them for their fur.[35] In the 19th century, it still occurred in Alpheius in the Peloponnese and in Mesolongi.[36]

Scandinavia

In Denmark, the Eurasian beaver became extinct around the year 1000. In 1999, 18 Eurasian beavers were reintroduced to the Flynder creek in a State Forest in northwestern Denmark that originated from Elbe river in Germany. This population nearly tripled until 2003 and spread in the whole creek.[37] As of 2009, this population was estimated at 139 individuals. In northern Zealand, 23 Eurasian beavers were reintroduced between 2009 and 2011.[38]

In Sweden, the Eurasian beaver had been hunted to extinction by around 1870.[16] Between 1922 and 1939, about 80 individuals were imported from Norway and introduced to 19 separate sites within the country. Beavers were reintroduced to central Norway's Ingdalselva River watershed on the Agdenes peninsula in Sør-Trøndelag County in 1968-1969. The area is hilly to mountainous with many small watersheds. Rivers are usually too steep along most of their length for beaver colonisation, so that suitable habitat is scattered, with rarely room for more than one territory in a habitat patch. While widespread signs of vagrant beavers were found, spread as a breeding animal was slowed by watershed divides in the hilly terrain. Suitable sites within watersheds were rapidly colonised. Some spread could only be plausibly explained by assuming travel through sheltered sea water in fjords.[39]

Some Eurasian beavers are present in Finland, but most of the Finnish population is a released North American beaver population.

Great Britain

The Eurasian beaver became extinct in Great Britain in the 16th century. The last reference to beavers in England dates to 1526.[40] A population of Eurasian beaver of unknown origin has been present on the River Otter, Devon in south-west England since 2008. An additional pair was released to increase genetic diversity in 2016.[41][42] As part of a scientific study, a pair of Eurasian beaver was released in 2011 near Dartmoor in southern Devon. The 13 beaver ponds now in place impacted flooding to the extent of releasing precipitation over days to weeks instead of hours.[43] Free-living beaver populations also occur around the River Tay and Knapdale areas in Scotland. The Knapdale population was released by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, while the other populations are of unknown origin. Sixteen beavers were released between 2009 and 2014 in Knapdale forest, Argyll. In 2016, the Scottish government declared that the beaver populations in Knapdale and Tayside could remain and naturally expand. This is the first successful reintroduction of a wild mammal in the United Kingdom.[44] In 2019, a beaver pair was reintroduced in East Anglia for the first time. The four hectare enclosure on a farm in North Essex is part of a flood risk reduction project designed to reduce property flooding. The impact on flooding, wildlife and rural tourism is monitored by a private landowner.[45]

Asia

In Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey, subfossil evidence of beavers extends down to the floodplains of the Tigris-Euphrates basin, and a carved stone stela dating between 1,000 and 800 BC in the Tell Halaf archaeological site along the Khabur River in northeastern Syria depicts a beaver.[46] Although accounts of 19th-century European visitors to the Middle East appear to confuse beavers with otters, a 20th-century report of beavers by Hans Kummerlöwe in the Ceyhan River drainage of southern Turkey includes the diagnostic red incisor teeth, flat, scaly tail, and presence of gnawed willow stems.[47] According to the Encyclopaedia Iranica, early Iranian Avestan and Pahlavi, and later Islamic literature, all reveal different words for otter and beaver, and castoreum was highly valued.[48] Johannes Ludwijk Schlimmer, a noted Dutch physician in 19th-century Iran reported beavers below the confluence of the Tigris and the Euphrates in small numbers, along the bank of the Shatt al-Arab in the provinces of Shushtar and Dezful."[49] Austen Layard reported finding beavers during his visit to the Kabur River in Syria the 1850s, but noted they were being rapidly hunted to extirpation.[50] Beavers were specifically sacred to Zoroastrianism (which also revered otters), and there were laws in place for unlawful killing of these animals.[51]

In China, a few hundred beavers live in the basin of the Ulungur River near the international border with Mongolia. The Bulgan Beaver Nature Reserve (Chinese: 布尔根河河狸自然保护区; 46°12′00″N 90°45′00″E) was established in 1980 to protect the creatures.[52]

Behaviour and ecology

The Eurasian beaver is a keystone species, as it helps to support the ecosystem which it inhabits. It creates wetlands, which provide habitat for European water vole, Eurasian otter and Eurasian water shrew. By coppicing waterside trees and shrubs it facilitates their regrow as dense shrubs, thus providing cover for birds and other animals. Beaver dams trap sediment, improve water quality, recharge groundwater tables and increase cover and forage for trout and salmon.[53] Also, abundance and diversity of vespertilionid bats increase, apparently because of gaps created in forests, making it easier for bats to navigate.[54]

Reproduction

Eurasian beavers have one litter per year, coming into estrus for only 12 to 24 hours, between late December and May, but peaking in January. Unlike most other rodents, beaver pairs are monogamous, staying together for multiple breeding seasons. Gestation averages 107 days and they average three kits per litter with a range of two to six kits. Most beavers do not reproduce until they are three years of age, but about 20% of two-year-old females reproduce.[55]

Effects on fish

Beaver ponds have been shown to have a beneficial effect on trout and salmon populations; in fact, many authors believe that the decline of salmonid fishes is related to the decline in beaver populations. A study of small streams in Sweden found that brown trout in beaver ponds were larger than those in riffle sections, and that beaver ponds provide habitat for larger trout in small streams during periods of drought.[56] These findings are similar to several studies of beaver effects on fish in North America. Brook trout, coho, and sockeye salmon were significantly larger in beaver ponds than those in unimpounded stream sections in Colorado and Alaska.[57][58] In addition, research in the Stillaguamish River basin in Washington found that extensive loss of beaver ponds resulted in an 89% reduction in coho salmon smolt summer production and an almost equally detrimental 86% reduction in critical winter habitat carrying capacity.[59] Migration of adult Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) may be limited by beaver dams during periods of low stream flows, but the presence of juveniles upstream from the dams suggests that the dams are penetrated by parr.[60] Downstream migration of Atlantic salmon smolts was similarly unaffected by beaver dams, even in periods of low flows.[60] Two-year-old Atlantic salmon parr in beaver ponds in eastern Canada showed faster summer growth in length and mass and were in better condition than parr upstream or downstream from the pond.[61] The importance of winter habitat to salmonids afforded by beaver ponds may be especially important (and underappreciated) in streams without deep pools or where ice cover makes contact with the bottom of shallow streams.[60] A 2003 study showed that Atlantic salmon and sea trout (S. trutta morpha trutta) spawning in the Numedalslågen River and 51 of its tributaries in southeastern Norway were unhindered by beaver.[62] In Norway, beaver dams are considered beneficial for brown and sea trout populations (these are potamodromous and anadromous forms of the same species). There, beaver ponds produce increased food for young fish and provide refuges for large adults heading upstream to spawn.[63]

Effects on bats

Beaver modifications to streams in Poland have been associated with increased bat activity. While overall bat activity was increased, Myotis bat species, particularly Myotis daubentonii, activity may be hampered in locations where beaver ponds allow for increased presence of duckweed. [64]

Effect on water quality

The misnomer ‘beaver fever’ was invented by the American press in the 1970s after an outbreak of Giardia lamblia, which causes giardiasis, was blamed on beavers. However, the outbreak area was also frequented by humans, who are generally the primary source of contamination of waters. In addition, many animals and birds carry this parasite.[65][66][67] Giardiasis affects humans in southeastern Norway, but a recent study found no Giardia in the beavers there.[68] Recent concerns point to domestic animals as a significant vector of Giardia, with young calves in dairy herds testing as high as 100% positive for Giardia.[69] New Zealand has Giardia but no beavers. In a 1995 paper recommending reintroduction of beaver to Great Britain, MacDonald stated that the only new diseases that beaver might convey to that country's birds and mammals, are rabies and tularemia - both diseases that should be preventable by statutory quarantine procedures and prophylactic treatment for tularemia.[63]

In addition, fecal coliform and streptococci bacteria excreted into streams by grazing cattle have been shown to be reduced by beaver ponds, where the bacteria are trapped in bottom sediments.[70]

In 2011, a Eurasian beaver pair was introduced to a beaver project site in West Devon, consisting of a 1.8 ha (4.4 acres) large enclosure with a 183 m (600 ft) long channel and one pond. Within five years, the pair created a complex wetland with an extensive network of channels, 13 ponds and dams. Survey results showed that the created ponds hold 31.75–111.05 kg/m2 (6.50–22.74 lb/sq ft) of sediment, which stores 13.40–18.40 t (13.19–18.11 long tons; 14.77–20.28 short tons) of carbon and 0.76–1.06 t (0.75–1.04 long tons; 0.84–1.17 short tons) of nitrogen. Concentrations of carbon and nitrogen were significantly higher in these ponds than farther upstream of this site. These results indicate that the beavers' activity contributes to reducing the effects of soil erosion and pollution in agricultural landscapes.[71]

Conservation

The Eurasian beaver Castor fiber was once widespread in Europe and Asia but by the beginning of the 20th century both the numbers and range of the species had been drastically diminished, mainly due to hunting.[1] At this time, the global population was estimated to be around 1,200 individuals, living in eight separate sub-populations.[1] In 2008, however, the IUCN granted the Eurasian Beaver a status of least concern, with the justification that the species had recovered sufficiently with the help of global conservation programmes.[1] Currently the largest numbers can be found across Europe, where reintroductions have been successful in 25 countries and conservation efforts are ongoing. However, populations in Asia remain small and fragmented, and are under considerable threat.[1][72]

Reintroduction into Scotland

The first sustained and significant population of wild-living beavers in the United Kingdom became established on the river Tay catchment in Scotland as early as 2001, and spread widely in the catchment, numbering from 20 to 100 individuals.[73] Because these beavers were either escapees from any of several nearby sites with captive beavers, or illegal releases, Scottish Natural Heritage initially planned to remove the Tayside beavers in late 2010.[74] Proponents of the beavers argued that no reason existed to believe that they were of "wrong" genetic stock, and that they should be permitted to remain.[73] One beaver was trapped by Scottish Natural Heritage on the River Ericht in Blairgowrie, Perthshire, in early December 2010, and was held in captivity in the Edinburgh Zoo. In March 2012 the Scottish Government reversed the decision to remove beavers from the Tay, pending the outcome of studies into the suitability of re-introduction.[75]

In 2005, the Scottish government had turned down a licence application for unfenced reintroduction. However, in late 2007, a further application was made by the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, Scottish Wildlife Trust and Forestry Commission Scotland[76] for a release project in Knapdale, Argyll.[77] This application, termed the Scottish Beaver Trial, was accepted, and the first beavers were released on 29 May 2009 after a 400-year absence,[78][79][76] with further releases in 2010.[80] In August 2010, at least two kits, estimated to be eight weeks old and belonging to different family groups, were seen in Knapdale Forest in Argyll.[81] Alongside the trial, the pre-existing population of beavers along the Tay was monitored and assessed.[75]

Following receipt of the results of the Scottish Beaver Trial, in November 2016 the Scottish Government announced that beavers could remain permanently, and would be given protected status as a native species within Scotland. Beavers will be allowed to extend their range naturally from Knapdale and the River Tay, however to aid this process and improve the health and resilience of the population a further 28 beavers will be released in Knapdale between 2017 and 2020.[82] A survey of beaver numbers during the winter of 2017-18 estimated that the Tayside population had increased to between 300-550 beavers, with beavers now also present in the catchment of the River Forth, and the Trossachs area.[83]

Reintroduction into England and Wales

A group of three beavers was spotted on the River Otter in Devon in 2013, apparently successfully bearing three kits the next year.[84][85] Following concern from local landowners and anglers, as well as farmers worrying that the beavers could carry disease, the government announced that it would capture the beavers and place them in a zoo or wildlife park. A sport-fishing industry lobbyist group, the Angling Trust, said, "it would be irresponsible even to consider re-introducing this species into the wild without first restoring our rivers to good health."[86] These actions were protested by local residents and campaign groups, with environmental journalist George Monbiot describing the government and anglers as 'control freaks': "I'm an angler, and the Angling Trust does not represent me on this issue...most anglers, in my experience, have a powerful connection with nature. The chance of seeing remarkable wild animals while waiting quietly on the riverbank is a major part of why we do it."[87] On 28 January 2015, Natural England declared that the beavers would be allowed to remain on condition that they were free of disease and of Eurasian descent. These conditions were found to be met on 23 March 2015, following the capture and testing of five of the beavers.[88] DNA testing showed that the animals were the once-native Eurasian beaver, and none of the beavers was found to be infected with Echinococcus multilocularis, tularaemia, or bovine TB. On 24 June 2015, video footage from local filmmaker Tom Buckley was featured on the BBC news website showing one of the wild Devon females with two live young.[89]

A study has been undertaken on the feasibility and desirability of a reintroduction of beavers to Wales by a partnership including the Wildlife Trusts, Countryside Council for Wales, Peoples Trust for Endangered Species, Environment Agency Wales, Wild Europe, and Forestry Commission Wales, with additional funding from Welsh Power Ltd. The resulting reports were published in 2012 with the launch of the Welsh Beaver Project, which is a partnership led by the Wildlife in Wales, and are downloadable from www.welshbeaverproject.org. A 2009 report by Natural England, the government’s conservation body, and the People's Trust for Endangered Species recommended that beavers be reintroduced to the wild in England.[53] This goal was realised in November 2016, when beavers were recognised as a British native species.[90]

In captivity

In 2001, the Kent Wildlife Trust with the Wildwood Trust and Natural England imported two families of Eurasian beavers from Norway to manage a wetland nature reserve. This project pioneered the use of beavers as a wildlife conservation tool in the UK. The success of this project has provided the inspiration behind other projects in Gloucestershire and Argyll. The Kent beaver colony lives in a 130-acre (0.53 km2) fenced enclosure at the wetland of Ham Fen. Subsequently, the population has been supplemented in 2005 and 2008. The beavers continue to help restore the wetland by rehydrating the soils.[91] Six Eurasian beavers were released in 2005 into a fenced lakeside area in Gloucestershire.[92] In 2007, a specially selected group of four Bavarian beavers was released into a fenced enclosure in the Martin Mere nature reserve in Lancashire.[93] The beavers hopefully will form a permanent colony, and the younger pair will be transferred to another location when the adults begin breeding again.[94] The progress of the group will be followed as part of the BBC's Autumnwatch television series. On November 19, 2011, a pair of beaver sisters was released into a 2.5-acre (1 ha) enclosure at Blaeneinion,[95] Furnace, Mid Wales.[96] A colony of beavers is also established in a large enclosure at Bamff, Perthshire.[97]

In June 2017, a pair of beavers (one male and one female, with hopes that they would become a breeding pair) were released into a secured area in Cornwall near Ladock. This was called The Beaver Project, and was funded through a very successful crowdfunded campaign led by the Cornwall Wildlife Trust. The aims of this project are split into several objectives; hydrology, water quality, impact on fish, ecology, and observation of the public perception of beaver reintroduction. As written on the Cornwall Wildlife Trust website: "The impacts of the beavers on water quantity and quality are being monitored by University of Exeter researchers who have had equipment on site for well over a year prior to the release of beavers. Some biodiversity monitoring is also being carried out including habitats, amphibians, bats, some invertebrate groups and fish. The project fits in scale between the fenced Devon trial and the River Otter Beaver Project. The potential to alleviate flooding is particularly important since the site is situated upstream of Ladock, a village increasingly affected by flooding."[98] There have been video updates and more since then, and there have recently been hopes that the pair have successfully bred pups, although this is yet to be confirmed.

On 24 July 2018 two Eurasian beavers were released into a fenced area 6.5 hectares (16 acres) in size surrounding Greathough Brook near Lydbrook in the Forest of Dean. The UK Government hopes that the presence of the beavers on Forestry Commission land will help to alleviate flooding in a natural way as the animals will construct dams and ponds, slowing the flow of water in the area. The village of Lydbrook was badly affected by flooding in 2012.[99]

The Environment Secretary Michael Gove, who attended the release, said:

"The beaver has a special place in English heritage and the Forest of Dean. This release is a fantastic opportunity to develop our understanding of the potential impacts of reintroductions and help this iconic species, 400 years after it was driven to extinction."[100]

See also

- Knapdale in Argyll

References

- Batbold, J.; Batsaikhan, N.; Shar, S.; Hutterer, R.; Kryštufek, B.; Yigit, N.; Mitsain, G.; Palomo, L. (2016). "Castor fiber". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T4007A115067136.

- Halley, D.; Rosell, F.; Saveljev, A. (2012). "Population and Distribution of Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber)" (PDF). Baltic Forestry. 18: 168–175. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- Kitchener, A. (2001). Beavers. Essex: Whittet Books. ISBN 978-1-873580-55-4.

- Rosell, F. & Steifetten, Ø. (2004). "Subspecies discrimination in the Scandinavian beaver (Castor fiber): combining behavioral and chemical evidence" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (6): 902–909. doi:10.1139/Z04-047. hdl:11250/2438047.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Rosell, F. & Thomsen, L. R. (2006). "Sexual dimorphism in territorial scent marking by adult Eurasian beavers (Castor fiber)". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 32 (6): 1301–1315. doi:10.1007/s10886-006-9087-y. hdl:11250/2438052. PMID 16770720.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Graf, P. M.; Wilson, R. P.; Qasem, L.; Hackländer, K.; Rosell, F. (2015). "The use of acceleration to code for animal behaviours; a case study in free-ranging Eurasian beavers Castor fiber". PLoS ONE. 10 (8): e0136751. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136751. PMC 4552556. PMID 26317623.

- Burnie, D. and Wilson, D. E. (2005). "Eurasian beaver". The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. London: Dorling Kindersley Ltd. p. 122. ISBN 0789477645.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Castor fiber". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. pp. 58–59. (in Latin)

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Species Castor fiber". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Kerr, R. (1792). "Beaver Castor". The Animal Kingdom or zoological system of the celebrated Sir Charles Linnaeus. Class I. Mammalia. Edinburgh & London: A. Strahan & T. Cadell. p. 221−224.

- Bechstein, J. M. (1801). "Der gemeine Biber". Gemeinnützige Naturgeschichte Deutschlands nach allen drey Reichen. 2. Leipzig: Siegfried Lebrecht Crusius. p. 910−928.

- Milishnikov, A. N.; Savel'Ev, A. P. (2001). "Genetic Divergence and Similarity of Introduced Populations of European Beaver (Castor fiber L., 1758) from Kirov and Novosibirsk Oblasts of Russia". Russian Journal of Genetics. 37 (1): 1022–7954. doi:10.1023/A:1009039113581.

- Halley, D. J. (2010). "Sourcing Eurasian beaver Castor fiber stock for reintroductions in Great Britain and Western Europe". Mammal Review. 41: 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2010.00167.x.

- Durka, W.; Babik, W.; Stubbe, M.; Heidecke, D.; Samjaa, R.; Saveljev, A.P.; Stubbe, A.; Ulevicius, A.; Stubbe, M. (2005). "Mitochondrial phylogeography of the Eurasian beaver Castor fiber L.". Molecular Ecology. 14 (12): 3843–3856. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02704.x. hdl:11250/2438022. PMID 16202100.

- DuCroz, J.-F.; Stubbe, M.; Saveljev, A. P.; Heidecke, D.; Samjaa, R.; Ulevicius, A.; Stubbe, A.; Durka, W. (2005). "Genetic variation and population structure of the Eurasian beaver Castor fiber in Eastern Europe and Asia". Journal of Mammalogy. 86 (6): 1059–1067. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2005)86[1059:GVAPSO]2.0.CO;2.

- Salvesen, S. (1928). "The Beaver in Norway". Journal of Mammalogy. 9 (2): 99–104. doi:10.2307/1373424. JSTOR 1373424.

- Nolet, B. A.; Rosell, F. (1998). "Come back of the beaver Castor fiber: an overview of old and new conservation problems". Biological Conservation. 83 (2): 165–173. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.503.6375. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(97)00066-9.

- Halley, D.; Rosell, F. (2003). "Population and distribution of European beavers (Castor fiber)". Lutra: 91–101. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011.

- Komarov, S. "Why Beavers Survived in the 19th Century". Innovations Report. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- Milishnikov, A. N. (2004). "Population-Genetic Structure of Beaver (Castor fiber L., 1758) Communities and Estimation of Effective Reproductive Size Ne of an Elementary Population". Russian Journal of Genetics. 40 (7): 772–781. doi:10.1023/B:RUGE.0000036527.85290.90.

- Ceña, J. C.; Alfaro, I.; Ceña, A.; Itoitz, U. X. U. E.; Berasategui, G.; Bidegain, I. (2004). "Castor europeo en Navarra y la Rioja" (PDF). Galemys. 16 (2): 91–98.

- Dewas, M.; Herr, J.; Schley, L.; Angst, C.; Manet, B.; Landry, P. and Catusse, M. (2012). "Recovery and status of native and introduced beavers Castor fiber and Castor canadensis in France and neighbouring countries". Mammal Review. 42 (2): 144–165. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2011.00196.x.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dolch, D.; Heidecke, D.; Teubner, J.; Teubner J. (2002). "Der Biber im Land Brandenburg". Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege in Brandenburg. 11 (4): 220–234.

- Spörrle, M. (2016). "Biber in Deutschland: Die Rache der Biber". Die Zeit. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Minnig, S.; Angst, C.; Jacob, G. (2016). "Genetic monitoring of Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) in Switzerland and implications for the management of the species". Russian Journal of Theriology. 15 (1): 20–27. doi:10.15298/rusjtheriol.15.1.04.

- "Het gaat te goed met de bevers - Binnenland - Voor nieuws, achtergronden en columns". volkskrant.nl. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Steeds meer overlast door bevers - Binnenland - Voor nieuws, achtergronden en columns". volkskrant.nl. 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Bobrów jest w Polsce ponad 100 tys. Czy jeszcze trzeba je chronić?". 2016.

- "Powódź - bobry do odstrzału". radiomerkury.pl. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Dispăruți de la 1824: Castorii repopulează apele din Covasna". Evenimentul Zilei. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- "Castorul a revenit în Delta Dunării, după 200 de ani de la dispariție". România Liberă. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- "Beaver Kills Man in Belarus". The Guardian. Associated Press. 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Αριστοτέλης 4th century BC: Των περί τα ζώα ιστοριών.

- Poulter, A. 2007: Nicopolis ad Istrum: A late Roman and early Byzantine City the Finds and Biological Remains.

- "Περιοχη Καστοριασ".

- Sidiropoulos, K.; Polymeni, R. M.; Legakis, A. (2016). "The evolution of Greek fauna since classical times". The Historical Review/La Revue Historique. 13: 127–146. doi:10.12681/hr.11559.

- Elmeros, M.; Madsen, A. B.; Berthelsen, J. P. (2003). "Monitoring of reintroduced beavers (Castor fiber) in Denmark" (PDF). Lutra. 46 (2): 153–162.

- Vilstrup, A. (2014). Assessment of the newly introduced beavers (Castor fiber) in Denmark and their habitat demands (PDF) (MSc thesis). Lund: Department of Biology, Lund University.

- Halley, D. J.; Teurlings, I.; Welsh, H. & Taylor, C. (2013). "Distribution and patterns of spread of recolonising Eurasian beavers (Castor fiber Linnaeus 1758) in fragmented habitat, Agdenes Peninsula, Norway". Fauna Norvegica. 32: 1–12. doi:10.5324/fn.v32i0.1438.

- Martin, H. T. (1892). Castorologia: Or The History and Traditions of the Canadian Beaver. W. Drysdale. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-665-07939-9.

- "Beaver spotted in Devon's River Otter by dog walker". BBC News. 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Aldred, J. (2014). "Wild beaver kits born in Devon". Guardian. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Lawton, G. (2018). "The secret site in England where beavers control the landscape". New Scientist. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- "More beavers reintroduced to Knapdale Forest". BBC News. 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- "Natural Flood Management Beavers - Spains Hall Estate". www.spainshallestate.co.uk. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Legge, A. J.; Rowley-Conwy, P. A. (1986). "The Beaver (Castor fiber L.) in the Tigris-Euphrates Basin". Journal of Archaeological Science. 13 (5): 469–476. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(86)90016-6.

- Kumerloeve, H. (1967). "Zur Verbreitung kleinasiatischer Raub- und Huftiere sowie einiger Grossnager". Säugetierkundliche Mitteilungen. 15 (4): 337–409.

- A'Lam, H. Encyclopaedia Iranica. IV(1). New York: Columbia University. pp. 71–74. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Schlimmer, J. L. (1874). Terminologie médico-pharmaceutique et anthropologique Française-Persane. Tehran, Iran: Lithographie d'Ali Gouli Khan. p. 115. ISBN 9781275998582. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Layard, A. H. (1853). Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. London, England: John Murray, Albemarle Street. p. 252. ISBN 9781275998582. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Chua, H.; Jianga, Z. (2009). "Distribution and conservation of the Sino-Mongolian beaver Castor fiber birulai in China". Oryx. 43 (2): 197–202. doi:10.1017/s0030605308002056.

- J. Gurnell; et al. REINTRODUCING BEAVERS TO ENGLAND Digest of a report The feasibility and acceptability of reintroducing the European beaver to England (Report). Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Ciechanowski, M.; Kubic, W.; Rynkiewicz, A.; Zwolicki, A. (2011). "Reintroduction of beavers Castor fiber may improve habitat quality for vespertilionid bats foraging in small river valleys" (PDF). European Journal of Wildlife Research. 57 (4): 737–747. doi:10.1007/s10344-010-0481-y.

- Dietland Müller-Schwarze; Lixing Sun (2003). The Beaver: Natural History of a Wetlands Engineer. Cornell University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8014-4098-4. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- Hägglund, Å.; Sjöberg, G. (1999). "Effects of beaver dams on the fish fauna of forest streams". Forest Ecology and Management. 115 (2–3): 259–266. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(98)00404-6.

- Rutherford, W.H. (1955). "Wildlife and environmental relationships of beavers in Colorado forests". Journal of Forestry: 803–806. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Murphy, M.L.; Heifetz, J.; Thedinga, J.F.; Johnson, S.W. & Koski, K.V. (1989). "Habitat utilisation by juvenile Pacific salmon (Onchorynchus) in the glacial Taku River, southeast Alaska". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 46 (10): 1677–1685. doi:10.1139/f89-213.

- M. M. Pollock; G. R. Pess; T. J. Beechie (2004). "The Importance of Beaver Ponds to Coho Salmon Production in the Stillaguamish River Basin, Washington, USA" (PDF). North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 24 (3): 749–760. doi:10.1577/M03-156.1. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Collen P, Gibson RJ (2001). "The general ecology of beavers (Castor spp.), as related to their influence on stream ecosystems and riparian habitats, and the subsequent effects on fish – a review". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 10: 439–461. doi:10.1023/A:1012262217012. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- D. B. Sigourney; B. H. Letcher; R. A. Cunjak (2006). "Influence of Beaver Activity on Summer Growth and Condition of Age-2 Atlantic Salmon Parr". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 135 (4): 1068–1075. doi:10.1577/T05-159.1.

- Howard Park; Ostein Cock Ronning (July 2007). "Low Potential for Restraint of Anadromous Salmonid Reproduction by Beaver Castor Fiber in the Numedalslågen River Catchment, Norway". River Research and Applications. 23 (7): 752–762. doi:10.1002/rra.1008.

- D. W. MacDonald; F.H. Tattersall; E. D. Brown; D. Balharry (1995). "Reintroducing the European Beaver to Britain: nostalgic meddling or restoring biodiversity?". Mammal Review. 25 (4): 161–200. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1995.tb00443.x.

- M. Ciechanowski; W. Kubic; A. Rynkiewicz; A. Zwolicki (2011). "Reintroduction of beavers Castor fiber may improve habitat quality for vespertilionid bats foraging in small river valleys". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 57: 737–747. doi:10.1007/s10344-010-0481-y.

- Gaywood, M.; Batty, D.; Galbraith, C. (2008). "Reintroducing the European Beaver in Britain". British Wildlife. 19 (6): 381–391.

- Erlandsen, S. L.; W. J. Bemrick (1988). "Waterborne giardiasis: sources of Giardia cysts and evidence pertaining to their implication in human infection". In P. M. Wallis; B. R. Hammond (eds.). Advances in Giardia research. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press. pp. 227–236.

- Erlandsen, SL, Sherlock, LA, Bemrick, WJ, Ghobrial, H, Jakubowski, W (1990). "Prevalence of Giardia spp. in Beaver and Muskrat Populations in Northeastern States and Minnesota: Detection of Intestinal Trophozoites at Necropsy Provides Greater Sensitivity than Detection of Cysts in Fecal Samples". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 56 (1): 31–36. PMC 183246. PMID 2178552. Retrieved 5 March 2011.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- F. Rosell; O. Rosef; H. Parker (2001). "Investigations of Waterborne Pathogens in Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber) from Telemark County, Southeast Norway". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 42 (4): 479–482. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-42-479. PMC 2203226. PMID 11957376.

- R. C. A. Thompson (November 2000). "Giardiasis as a re-emerging infectious disease and its zoonotic potential". International Journal for Parasitology. 30 (12–13): 1259–1267. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00127-2. PMID 11113253.

- Quentin D. Skinner; John E. Speck; Michael Smith; John C. Adams (March 1984). "Stream Water Quality as Influenced by Beaver within Grazing Systems in Wyoming". Journal of Range Management. 37 (2): 142–146. doi:10.2307/3898902. JSTOR 3898902.

- Puttock, A.; Graham, H. A.; Carless, D.; Brazier, R. E. (2018). "Sediment and nutrient storage in a beaver engineered wetland". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 43 (11): 2358–2370. doi:10.1002/esp.4398.

- "Scottish Beaver Frequently Asked Questions". www.scottishbeavers.org.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- Duncan J. Halley (January 2011). "Sourcing Eurasian beaver Castor fiber stock for reintroductions in Great Britain and Western Europe". Mammal Review. 41: 40–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2010.00167.x.

- "Feral beavers in Tayside 'will be trapped'". BBC News. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- "Plan to trap River Tay beavers reversed by ministers". BBC News. 16 March 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "About the trial". www.scottishbeavers.org.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- Watson, Jeremy (30 September 2007). "Beavers dip a toe in the water for Scots return". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- "UK | Scotland | Glasgow, Lanarkshire and West | Beavers to return after 400 years". BBC News. 25 May 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "UK | Scotland | Glasgow, Lanarkshire and West | Beavers return after 400-year gap". BBC News. 29 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "New breeding beaver pair released in Scotland". BBC News. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- "'First' newborn beavers spotted in the Argyll Forest". BBC News. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- "Beaver population increased in Knapdale". Scottish Wildlife Trust. 28 November 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "SNH Research Report 1013 - Survey of the Tayside area beaver population 2017-2018" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2018. p. iii. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Beaver spotted in Devon's River Otter by dog walker". BBC News. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Aldred, Jessica (17 July 2014). "Wild beaver kits born in Devon". Guardian. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Lloyd, Mark. "Angling Trust welcomes action to remove beavers from Devon River". Angling Trust. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- Monbiot, George (4 July 2014). "Stop the control freaks who want to capture England's wild beavers". Guardian. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- "Devon's Wild Beavers". Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- Marshall, Claire (24 June 2015). "England's wild beaver colony has kits". BBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- Carrell, S. (2016). "Beavers given native species status after reintroduction to Scotland". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Born to be Wild! Beavers breed at Kent reserve". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- "Beavers in 'wild' after centuries". BBC News. 28 October 2005.

- "Beavers are back after 500 years". BBC News. July 2007.

- "Meet the Beavers". Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust. Archived from the original on 28 January 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- "Beavers". Blaeneinion. 19 November 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Rachael Garside (10 February 2012). "Blogs - Wales - Beavers return to Ceredigion". BBC. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Vines, Gail, "The beaver: destructive pest or climate saviour?", 22 August 2007, New Scientist 2618: 42-45. Article on beaver reintroduction". Newscientist.com. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Cornwall Beaver Project | Cornwall Wildlife Trust". www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Morris, Steven (24 July 2018). "Beavers released in Forest of Dean as solution to flooding". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "Beavers arrive in the Forest of Dean". gov.uk. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Castor fiber. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Castor fiber |