Enlargement of the eurozone

The enlargement of the eurozone is an ongoing process within the European Union (EU). All member states of the European Union, except Denmark which negotiated opt-outs from the provisions, are obliged to adopt the euro as their sole currency once they meet the criteria, which include: complying with the debt and deficit criteria outlined by the Stability and Growth Pact, keeping inflation and long-term governmental interest rates below certain reference values, stabilising their currency's exchange rate versus the euro by participating in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II), and ensuring that their national laws comply with the ECB statute, ESCB statute and articles 130+131 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The obligation for EU member states to adopt the euro was first outlined by article 109.1j of the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which became binding on all new member states by the terms of their treaties of accession.

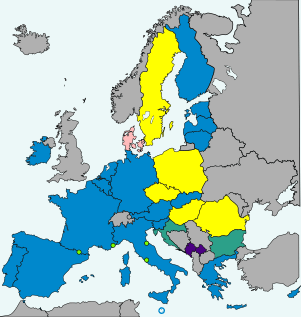

As of 2020, there are 19 EU member states in the eurozone, of which the first 11 (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain) introduced the euro on 1 January 1999 when it was electronic only. Greece joined 1 January 2001, one year before the physical euro coins and notes replaced the old national currencies in the eurozone. Subsequently, the following seven countries also joined the eurozone on 1 January in the mentioned year: Slovenia (2007), Cyprus (2008), Malta (2008), Slovakia (2009),[1] Estonia (2011),[2] Latvia (2014)[3] and Lithuania (2015).

Seven remaining states are on the enlargement agenda: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Sweden. Denmark has opted out and is therefore not obliged to join, though should the country decide to do so it may join the eurozone with little difficulty as Denmark is already part of the ERM II. The United Kingdom also had an opt-out until it left the EU on 31 January 2020.

Accession procedure

All EU members which have joined the bloc since the signing of the Maastricht treaty in 1992 are legally obliged to adopt the euro once they meet the criteria, since the terms of their accession treaties make the provisions on the euro binding on them. In order for a state to formally join the eurozone, enabling them to mint euro coins and get a seat at the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Eurogroup, a country must be a member of the European Union and comply with five convergence criteria, which were initially defined by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. These criteria include: complying with the debt and deficit criteria outlined by the Stability and Growth Pact, keeping inflation and long-term governmental interest rates below reference values, and stabilising their currency's exchange rate versus the euro. Generally, it is expected that the last point will be demonstrated by two consecutive years of participation in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II),[4] though according to the Commission "exchange rate stability during a period of non-participation before entering ERM II can be taken into account."[5] The country must also ensure that their national laws are compliant with the ECB statute, ESCB statute and articles 130+131 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Since the convergence criteria require participation in the ERM, and non-eurozone states are responsible for deciding when to join ERM, they can ultimately control when they adopt the euro by staying outside the ERM and thus deliberately failing to meet the convergence criteria until they wish to. In some non-eurozone states without an opt-out, there has been discussion about holding referendums on approving their euro adoption.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] Of the 16 states which have acceded to EU since 1992, the only state to have staged a euro referendum to date is Sweden, which in 2003 rejected its government's proposal to adopt the euro in 2006.

Convergence criteria

The convergence progress for the newly accessed EU member states, is supported and evaluated by the yearly submission of the "Convergence programme" under the Stability and Growth Pact. As a general rule, the majority of economic experts recommend for newly accessed EU member states with a forecasted era of catching up and a past record of "macroeconomic imbalance" or "financial instability", that these countries first use some years to address these issues and ensure "stable convergence", before taking the next step to join the ERM II, and as the final step (when complying with all convergence criteria) ultimately adopt the euro. In practical terms, any non-euro EU member state can become an ERM II member whenever they want, as this mechanism does not define any criteria to comply with. Economists however consider it to be more desirable for "unstable countries", to maintain their flexibility of having a floating currency, rather than getting an inflexible and partly fixed currency as an ERM II member. Only at the time of being considered fully "stable", the member states will be encouraged to enter into ERM II, in which they need to stay for a minimum of two years without presence of "severe tensions" for their currency, while at the same time also ensuring compliance with the other four convergence criteria, before finally being approved to adopt the euro.[15]

| Convergence criteria (valid for the compliance check conducted by ECB in their May 2018 Report) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | HICP inflation rate[16][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[17] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[18][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

| Budget deficit to GDP[19] | Debt-to-GDP ratio[20] | ERM II member[21] | Change in rate[22][23][nb 3] | ||||

| Reference values[nb 4] | Max. 1.9%[nb 5] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

None open (as of 3 May 2018) | Min. 2 years (as of 3 May 2018) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2017) |

Max. 3.2%[nb 7] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

Yes[24][25] (as of 20 March 2018) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2017)[26] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2017)[26] | ||||||

| EU members (outside the eurozone) | |||||||

| 1.4% | None | No | 0.0% | 1.4% | No | ||

| -0.9% (surplus) | 25.4% | ||||||

| 1.3% | None | No | 0.9% | 2.6% | No | ||

| -0.8% (surplus) | 78.0% | ||||||

| 2.2% | None | No | 2.6% | 1.3% | No | ||

| -1.6% (surplus) | 34.6% | ||||||

| 1.0% | None | 19 years, 2 months | 0.1% | 0.6% | Unknown | ||

| -1.0% (surplus) | 36.4% | ||||||

| 2.2% | None | No | 0.7% | 2.7% | No | ||

| 2.0% | 73.6% | ||||||

| 1.4% | None | No | 2.4% | 3.3% | No | ||

| 1.7% | 50.6% | ||||||

| 1.9% | None | No | -1.7% | 4.1% | No | ||

| 2.9% | 35.0% | ||||||

| 1.9% | None | No | -1.8% | 0.7% | No | ||

| -1.3% (surplus) | 40.6% | ||||||

- Notes

- The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2018.[24]

- Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[24]

- The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

- Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[24]

- Reference values for the HICP criteria and interest rate criteria

The compliance check above was conducted in June 2014, with the HICP and interest rate reference values specifically applying for the last assessment month with available data (April 2014). As reference values for HICP and interest rates are subject for monthly changes, any EU member state with a euro derogation has the right to ask for a renewed compliance check at any time during the year. For this potential extra assessment, the table below feature Eurostat's monthly publication of values being used in the calculation process to determine the reference value (upper limit) for HICP inflation and long-term interest rates, where a certain fixed buffer value is added to the moving unweighted arithmetic average of the three EU Member States with the lowest HICP inflation rates (ignoring states classified as "outliers").

The black values in the table are sourced by the officially published convergence reports, while the lime-green values are only qualified estimates, not confirmed by any official convergence report but sourced by monthly estimation reports published by the Polish Ministry of Finance. The reason why the lime-green values are only estimates is that the "outlier" selection (ignoring certain states from the reference value calculation) besides depending on a quantitative assessment also depends on a more complicated overall qualitative assessment, and hence it can not be predicted with absolute certainty which of the states the Commission will deem to be outliers. So any selection of outliers by the lime-green data lines shall only be regarded as qualified estimates, which potentially could be different from those outliers which the Commission would have selected if they had published a specific report at the concerned point of time.[nb 1]

The national fiscal accounts for the previous full calendar year are released each year in April (next time 24 April 2019).[33] As the compliance check for both the debt and deficit criteria always awaits this release in a new calendar year, the first possible month to request a compliance check will be April, which would result in a data check for the HICP and interest rates during the reference year from 1 April to 31 March. Any EU member state may also ask the European Commission to conduct a compliance check, at any point of time during the remainder of the year, with HICP and interest rates always checked for the past 12 months – while debt and deficit compliance always will be checked for the three-year period encompassing the last completed full calendar year and the two subsequent forecast years.[34][35] As of 10 August 2015, none of the remaining euro derogation states without an opt-out had entered ERM II,[36] which makes it highly unlikely that any of them will request that the European Commission conduct an extraordinary compliance check ahead of the publication of the next regular convergence report scheduled June 2016.

Additional requirements

In the wake of the financial crisis, Eurozone governments have sought to apply additional requirements on acceding countries. Bulgaria, initially aiming to join the banking union after its ERM accession agreed to enter into closer cooperation with it simultaneously to joining ERM II, requiring its banks to first undergo stress tests. Bulgaria also agreed to reinforce supervision of the non-bank financial sector and fully implement EU anti money-laundering rules. While the reforms from the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (which applies only to Bulgaria and Romania) were also expected, leaving the CVM is not a precondition.[37]

Changeover plan

Each country aspiring to adopt the euro has been requested by the European Commission to develop a "strategy for criteria compliance" and "national euro changeover plan". In the "changeover plan", the country can select from between three scenarios for euro adoption:[38]

- Madrid scenario (with a transition period between euro adoption day and the physical circulation of euros)

- Big-bang scenario (euro adoption day coincides with the first day of circulating euros)

- Big-bang scenario with phaseout (same as the second scenario, but with a transitional period for legal documents like contracts to be denoted in euros)

The second scenario is recommended for candidate countries, while the third is only advised if at a late stage in the preparational process they experience technical difficulties (i.e. with IT systems), which would make an extended transitional period for the phasing out of the old currency at the legal level a necessity.[38] The European Commission has published a handbook detailing how states should prepare for the changeover. It recommends that a national steering committee is established at a very early stage of the state's preparation process, with the task to outline detailed plans for the following five actions:[39]

- Prepare the public with an information campaign and dual price display.

- Prepare the public sector's introduction at the legal level.

- Prepare the private sector's introduction at the legal level.

- Prepare the vending machine industry so that they can deliver adjusted and quality tested vending machines.

- Frontload banks as well as public and private retail sectors several months (no earlier than 4 months[40]) ahead of the euro adoption day, with their needed supply of euro coins and notes.

The table below summarises each candidate country's national plan for euro adoption and currency changeover.[41]

| State | Coordinating institution | Changeover plan (latest version) |

Introduc-tion[42] | Dual circulation period |

Exchange of coins period | Dual price display | Coin design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordination Council for the preparation of Bulgaria for eurozone membership (founded July 2015)[43] |

Only published a strategy plan[44] |

Big-Bang | 1 month | Not yet decided by the Central bank | Start 1 month after Council approval of euro adoption, and lasts until 12 months after adoption | Approved | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | Competition under consideration | |

| National Coordination Group (founded Feb.2006) |

Approved Apr.2007[45] | Big-Bang | 2 weeks | Banks: 6 months, Central bank: 5 years |

Start 1 month after Council approval of euro adoption, and lasts until 12 months after adoption | Competition under consideration | |

| – | The original plan from 2000[46] is no longer valid, and will be replaced by a new plan ahead of a referendum. | Madrid scenario (as per the 2000 plan) |

4 weeks or 2 months (as per the 2000 plan) |

Central bank: 30 years (as per the 2000 plan) |

Start on the day of euro circulation, and last 4 weeks or 2 months (as per the 2000 plan) |

In 2000, prior to the euro referendum that year, a possible coin design was published. [47] | |

| National Euro Coordination Committee (founded Sep.2007) |

Updated Dec.2009[48] | Big-Bang | less than 1 month (not decided yet) |

Central bank: 5 years |

Start 1 day after Council approval of euro adoption, and lasts until 6 months after adoption | Not yet decided | |

| Government Plenipotentiary for the Euro Adoption in Poland National Coordination Committee for Euro Changeover

Coordinating Council |

Approved in 2011 (updated plan in preparation)[nb 2] |

– | – | – | – | Public survey under consideration | |

| Interministerial Committee for changeover to euro (founded May 2011) |

– | – | 11 months[51] | – | – | Not yet decided | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | Not under consideration |

Alternate proposals

The European microstates of Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and the Vatican City are not covered by convergence criteria, but by special monetary agreements that allow them to issue their own euro coins. However, they have no input into the economic affairs of the euro.[52] In 2009 the authors of a confidential International Monetary Fund (IMF) report suggested that in light of the ongoing global financial crisis, the EU Council should consider granting EU member states which are having difficulty complying with all five convergence criteria the option to "partially adopt" the euro, along the lines of the monetary agreements signed with the microstates outside the EU. These states would gain the right to adopt the euro and issue a national variant of euro coins, but would not get a seat in ECB or the Eurogroup until they met all the convergence criteria.[53] However, the EU has not agreed to this alternative accession process.

Historical enlargements

| Country | Currency | Code | Rate[54] | Fixed on | Yielded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Austrian schilling | ATS | 13.7603 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Belgium | Belgian franc | BEF | 40.3399 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Cyprus | Cypriot pound | CYP | 0.585274 | 2007-07-10 | 2008-01-01 |

| Netherlands | Dutch guilder | NLG | 2.20371 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Estonia | Estonian kroon | EEK | 15.6466 | 2010-07-13 | 2011-01-01 |

| Finland | Finnish markka | FIM | 5.94573 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| France | French franc | FRF | 6.55957 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Germany | German mark | DEM | 1.95583 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Greece | Greek drachma | GRD | 340.75 | 2000-06-19 | 2001-01-01 |

| Ireland | Irish pound | IEP | 0.787564 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Italy | Italian lira | ITL | 1,936.27 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Latvia | Latvian lats | LVL | 0.702804 | 2013-07-09 | 2014-01-01 |

| Lithuania | Lithuanian litas | LTL | 3.4528 | 2014-07-23 | 2015-01-01 |

| Luxembourg | Luxembourgish franc | LUF | 40.3399 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Malta | Maltese lira | MTL | 0.4293 | 2007-07-10 | 2008-01-01 |

| Monaco | Monégasque franc | MCF | 6.55957 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Portugal | Portuguese escudo | PTE | 200.482 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| San Marino | Sammarinese lira | SML | 1,936.27 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Slovakia | Slovak koruna | SKK | 30.126 | 2008-07-08 | 2009-01-01 |

| Slovenia | Slovenian tolar | SIT | 239.64 | 2006-07-11 | 2007-01-01 |

| Spain | Spanish peseta | ESP | 166.386 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

| Vatican City | Vatican lira | VAL | 1,936.27 | 1998-12-31 | 1999-01-01 |

The eurozone was born with its first 11 Member States on 1 January 1999. The first enlargement of the eurozone, to Greece, took place on 1 January 2001, one year before the euro had physically entered into circulation. Along with the formal eurozone states, the euro also replaced currencies in four microstates, Kosovo, and Montenegro who all used the currencies of one of the member countries. Denmark and Sweden held referendums on joining the euro, but voters voted down the referendums leading both to remain outside. The first enlargements after the euro entered circulation were to states which joined the EU in 2004; namely Slovenia in 2007, followed by Cyprus and Malta in 2008, Slovakia in 2009, Estonia in 2011, Latvia in 2014, and Lithuania in 2015.

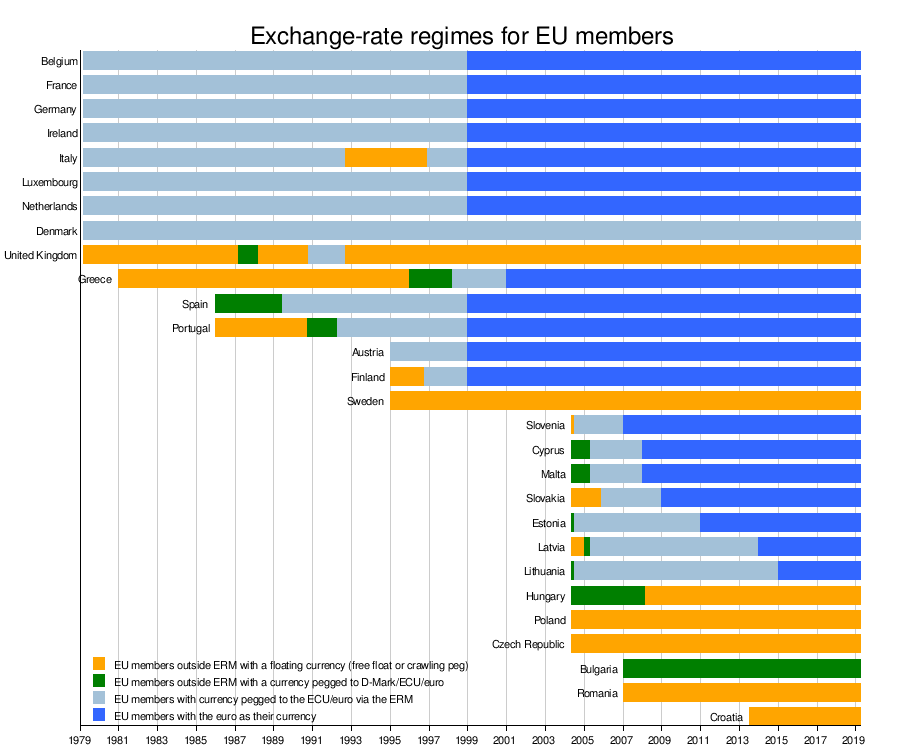

Exchange-rate regime for EU members

The chart below provides a full historical summary of exchange-rate regimes for EU members since the European Monetary System with its Exchange Rate Mechanism and the related new common currency ECU was born on 13 March 1979. The euro replaced the ECU 1:1 at the exchange rate markets, on 1 January 1999. During 1979–1999, the German mark functioned as a de facto anchor for the ECU, meaning there was only a minor difference between pegging a currency against ECU and pegging it against the German mark.

Sources: EC convergence reports 1996-2014, Italian lira , Spanish peseta, Portuguese escudo, Finish markka, Greek drachma, UK pound

Future enlargements

All members who joined the union from 1995 onwards are required by treaty to adopt the euro as soon as they meet the criteria; only Denmark obtained treaty opt-outs from participation in the Maastricht Treaty when the euro was agreed upon. For the others, the single currency was a requirement of EU membership.

| Non-Eurozone EU member | Currency | EU join date | ERM II join date[36] | Central rate per €1[36] | Government policy | Public opinion | Convergence criteria | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Code | ||||||||

| Lev | BGN | 2007-01-01 | None | 1.95583[nb 3] | ERM-II by July 2020, Euro by 1 January 2023[56] | 35% in favour (2018)[57] | All except ERM-II and legislation | Coins design approved | |

| Kuna | HRK | 2013-07-01 | None | Free floating | ERM-II by the end of 2020, Euro by 2025[58] | 40% in favour (2018)[57] | Not compliant | ||

| Koruna | CZK | 2004-05-01 | None | Free floating | Not on government's agenda[59] | 21% in favour (2018)[57] | Not compliant | ||

| Krone | DKK | 1973-01-01 | 1999-01-01 | 7.46038 | Not on government's agenda[60] | 30% in favour (2018)[57] | Fully compliant | Treaty opt-out from euro membership, rejected membership via referendum | |

| Forint | HUF | 2004-05-01 | None | Free floating | Not on government's agenda[61] | 53% in favour (2018)[57] | Not compliant | ||

| Złoty | PLN | 2004-05-01 | None | Free floating | Not on government's agenda[62] | 36% in favour (2018)[57] | Not compliant | ||

| Leu | RON | 2007-01-01 | None | Free floating | ERM-II by 2024[63] | 55% in favour (2018)[57] | Not compliant | ||

| Krona | SEK | 1995-01-01 | None | Free floating | Not on government's agenda[64] | 29% in favour (2018)[57] | All except ERM-II and legislation | Rejected membership via referendum (2003)[nb 4] | |

- European Union (EU) member states

-

5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden).

- Non-EU member states

Bulgaria

The lev is not part of ERM II, but since the launch of the euro in 1999, it has been pegged to the euro at a fixed rate of €1 = BGN 1.95583 through a strictly managed currency board.[nb 3] In all of the three latest annual assessment reports, Bulgaria managed to comply with four out of the five economic convergence criteria for euro adoption, only failing to comply with the criteria requiring the currency of the state to have been a stable ERM II member for a minimum of two years.[65][66][67] The former chief inspector of the Bulgarian National Bank, Kolyo Paramov, in office when the currency board of the state was established, believes that adoption of the euro soon would "trigger a number of positive economic effects": Sufficient money supply (leading to increased lending which is needed to improve economic growth), getting rid of the currency board which prevents the national bank functioning as a lender of last resort to rescue banks in financial troubles, and finally private and public lending would benefit from lower interest rates (at least half as high).[68]

Before 2015 it had been government policy to hold-off application until the European sovereign-debt crisis had resolved[69][70] but with the election of Boyko Borisov, Bulgaria began pursuing membership. In January 2015, Finance Minister Vladislav Goranov aimed to apply during the current government. He began talks with the Eurogroup[71] and established a co-ordination council to prepare for membership.[72][43] Following the 2017 parliamentary elections Borisov's government was re-elected. Borisov stated that he intended to apply to join ERM II[73] but Goranov elaborated that the government would only seek to join once the eurozone states were ready to approve the application, and that he expected to have clarity of this by the end of 2017.[74] On taking the presidency of the Council of the European Union in January 2018, Prime Minister Boyko Borisov indicated no clarification had been given but announced he was going to pursue applications for both ERM II and Schengen by July regardless.[75][76][77][78] Bulgaria sent a letter to the Eurogroup at the end of June on its desire to participate in ERM II, and issued a commitment to enter into a "close cooperation" agreement with the banking union that July.[79][80]

In July 2019 some extra conditions were requested by Eurozone governments, namely that Bulgaria;[37]

- Join the banking union at the same time as ERM (meaning Bulgaria's banks must first pass stress-tests).

- Reinforce supervision of the non-bank financial sector and fully implement EU anti money-laundering rules.

- Thoroughly implement the reforms from the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM).

While the CVM reforms are mentioned, and progress in judicial reform and organised crime is expected, leaving the CVM is not a precondition.[37]

According to the latest statement of Finance Minister Vladislav Goranov as of December, 2019, Bulgaria expects to join ERM II by April, 2020 and to adopt the euro by the 1st of January, 2023 at the latest.

Croatia

Croatia's currency, the kuna, has used the euro (and prior to that one of the euro's major predecessors, the Deutsche Mark) as its main reference since its creation in 1994, and a long-held policy of the Croatian National Bank has been to keep the kuna's exchange rate with the euro within a relatively stable range. Before Croatia became a member of the EU on 1 July 2013, Boris Vujčić, governor of the Croatian National Bank, stated that he would like the kuna to be replaced by the euro as soon as possible after accession.[81] In 2013 the European Central Bank expected Croatia to be approved for ERM II membership at the earliest in 2016, leading to a subsequent euro adoption at the earliest in 2019.[82] In Croatia's first assessment under the convergence criteria in May 2014, the country satisfied the inflation and interest rate criteria, but did not satisfy the public finances and ERM membership criteria.[83]

In April 2015, President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic stated in a Bloomberg interview she was "confident that Croatia would introduce the euro by 2020", while Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic said at the government session that "some occasional announcements when Croatia will introduce the euro shouldn't be taken seriously. We'll try to make it as soon as possible, but I distance myself from any dates and ask that you don't comment on it. When the country is ready, it will enter the euro area. The criteria are very clear."[84] In November 2017, Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic said he was aiming for Croatia to join ERM II by 2020 and to introduce the Euro by 2023.[85] On 23 November 2019, European Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis said that Croatia could join ERM II in the second half of 2020.[86]

Czech Republic

Following their accession to the EU in May 2004, the Czech Republic aimed to replace the koruna with the euro in 2010, however this was postponed indefinitely.[87] The European sovereign-debt crisis further decreased the Czech Republic's interest in joining the eurozone.[88] There have been calls for a referendum before adopting the euro, with former Prime Minister Petr Nečas saying that the conditions had significantly changed since their accession treaty was ratified.[89] President Miloš Zeman also supports a referendum, but does still advocate adoption of the euro.[90]

Adoption was supported under Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka[91] but supported a recommendation from the Czech National Bank to refrain from setting a target date.[92] The government agreed that if it was re-elected in 2017 then it would agree a roadmap for adoption by 2020,[93] however the election was lost to Andrej Babiš who is against euro adoption in the near-term.[94]

Denmark

Denmark has pegged its krone to the euro at €1 = DKK 7.46038 ± 2.25% through the ERM II since it replaced the original ERM on 1 January 1999. During negotiations of the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, Denmark secured a protocol which gave it the right to decide if and when they would join the euro. Denmark subsequently notified the Council of the European Communities of their decision to opt out of the euro. This was done in response to the Maastricht treaty having been rejected by the Danish people in a referendum earlier that year. As a result of the changes, the treaty was ratified in a subsequent referendum held in 1993. On 28 September 2000, a euro referendum was held in Denmark resulting in a 53.2% vote against the government's proposal to join the euro.

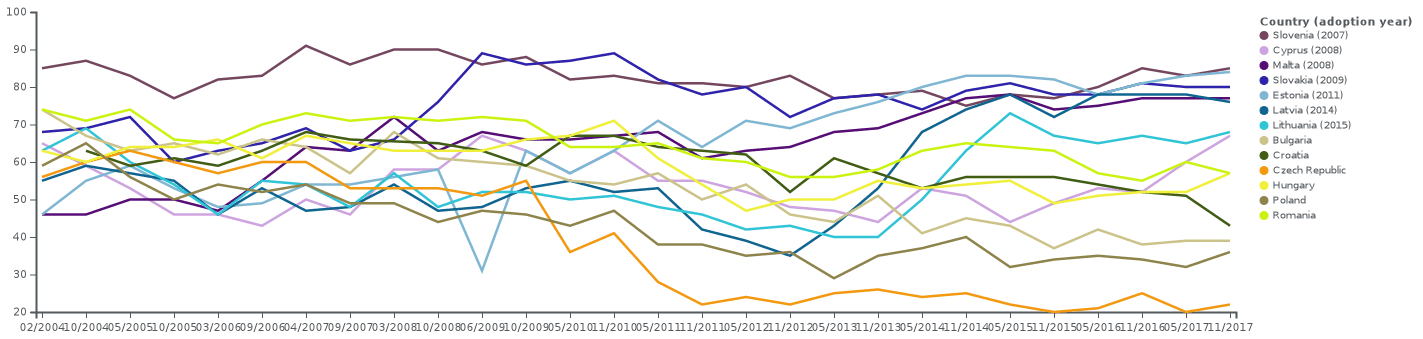

Since 2007, the Danish government has discussed holding another referendum on euro adoption.[95] However the political and financial uncertainty due to the European government-debt crisis led this to be postponed.[96] Opinion polls, which had generally favoured euro adoption from 2002 to 2010, showed a rapid decline in support during the height of the EU debt crisis,[97] reaching a low in May 2012 with 26% in favor towards 67% against while 7% were in doubt.[98]

Hungary

With their accession to the EU in 2004, Hungary began planning to adopt the euro in place of the forint. However, the country's high deficit delayed this. After the 2006 election, Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány introduced austerity measures, reducing the deficit to less than 5% in 2007 from 9.2%. In February 2011, newly elected Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, of the soft eurosceptic Fidesz party, made clear that he did not expect the euro to be adopted in Hungary before 1 January 2020.[99] Orbán said the country was not yet ready to adopt the currency and they will not discuss the possibility until the public debt reaches a 50% threshold.[100] The public debt-to-GDP ratio was 81.0% when Orban's 50% target was set in 2011, and it is currently forecast to decline to 73.5% in 2016.[101] In April 2013, Viktor Orbán further added that Hungarian purchasing power parity weighted GDP per capita must also reach 90% of the eurozone average.[102] Shortly after Viktor Orbán had been re-elected as Prime Minister for another four-year term in April 2014,[103] the Hungarian Central Bank announced they plan to distribute a new series of Forint bank notes in 2018.[104] In June 2015, Orbán himself declared that his government would no longer entertain the idea of replacing the forint with the euro in 2020, as was previously suggested, and instead expected the forint to remain "stable and strong for the next several decades".[105]

In July 2016, National Economy Minister Mihály Varga suggested that country could adopt the euro by the "end of the decade", but only if economic trends continue to improve and the common currency becomes more stable.[106][107] While Varga backed away from that, saying convergence was still needed, Sándor Csányi (the head of the country's largest bank and ranked the second most influential man in Hungary) argued that further integration of the eurozone would provide a likely catalyst as Hungary would not want to be left out of closer integration. Attila Chikan, a professor of economics at Corvinus University, and a former economy minister to Orban, added that "Orban is at once very pragmatic and impulsive, he can make decisions very fast and sometimes on unexpected grounds."[108]

Poland

The Polish government in 2012 under Prime Minister Donald Tusk had favoured euro adoption, however it did not have the required majority in the Sejm to amend the constitution due to the opposition of the Law and Justice Party to the euro.[109][110][111] Further opposition arose due to the on-going sovereign-debt crisis, with the Polish National Bank recommending Poland wait until the Eurozone had overcome the crisis.[112] The leader of the Law and Justice Party, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, stated in 2013 that "I do not foresee any moment when the adoption of the euro would be advantageous for us" and called for a referendum on euro adoption.[113] Donald Tusk responded saying he was open to a referendum, as part of a package in Parliament to approve the constitutional amendment.[114] However the 2015 Polish elections were won by Law and Justice who not only opposed any further moves towards membership, but whose relations with the EU has degenerated due to a potential violation of EU values by Poland. A group of Polish economists have suggested that euro adoption could be a way of smoothing over relations from the dispute.[115]

Polls have generally showed that Poles are opposed to adopting the euro straight away,[88][116] with a eurobarometer poll in April 2015 showing that 44 per cent of Polish people are in favour of introducing the euro (a decrease of 1 per cent from 2014), whereas 53 per cent are opposed (no change from 2014).[117][118][118] However, polls conducted by TNS Polska throughout 2012–2015 have consistently shown support for eventually adopting the euro,[119][120][121][122][123][124][125][126][127] though that support depends on the target date. According to the latest TNS Polska poll from June 2015, the share who supported adoption was 46% against 41%. When asked about the appropriate timing, the supporters were divided into three groups of equal size, with 15% advocating for adoption within the next 5 years, another 14% preferring it should happen between 6–10 years from now, and finally 17% arguing it should happen more than 10 years from now.[127]

Romania

Originally, the euro was scheduled to be adopted by Romania in place of the leu by 2014.[128] In April 2012 the Romanian convergence report submitted under the Stability and Growth Pact listed 1 January 2015 to be the target date for euro adoption.[129] In April 2013 Prime Minister Victor Ponta has stated that "eurozone entry remains a fundamental objective for Romania but we can't enter poorly prepared", and that 2020 was a more realistic target.[130] The Romanian Central Bank governor, Mugur Isărescu, admitted the target was ambitious, but obtainable if the political parties passed a legal roadmap for the required reforms to be implemented, and clarified this roadmap should lead to Romania entering ERM II only on 1 January 2017 so the euro could be adopted after two years of ERM II membership on 1 January 2019.[131]

As of April 2015, the Romanian government concluded it was still on track to attain its target for euro adoption in 2019, both in regards of ensuring full compliance with all nominal convergence criteria and in regards of ensuring a prior satisfying degree of "real convergence". The Romanian target for "real convergence" ahead of euro adoption, is for its GDP per capita (in purchasing power standards) to be above 60% of the same average figure for the entire European Union, and according to the latest outlook, this relative figure was now forecast to reach 65% in 2018 and 71% in 2020,[132] after having risen at the same pace from 29% in 2002 to 54% in 2014.[133] However, in September 2015 Romania's central bank governor Mugur Isarescu said that the 2019 target was no longer realistic.[134] The target date was initially 2022, as Teodor Meleșcanu, the foreign minister of Romania declared on 28 August 2017 that, as they "meet all formal requirements", Romania "could join the currency union even tomorrow". However, he thought Romania "will adopt the euro in five years."[135] In March 2018, however, members of the ruling Social Democratic Party (PSD) voted at an extraordinary congress to back a 2024 target year to adopt the euro as Romania's currency.[136]

Sweden

Although Sweden is required to replace the krona with the euro eventually, it maintains that joining the ERM II, a requirement for euro adoption, is voluntary,[137][138] and has chosen to not join pending public approval by a referendum, thereby intentionally avoiding the fulfillment of the adoption requirements. On 14 September 2003 56% of Swedes voted against adopting the euro in a referendum.[139] Most of Sweden's major parties believe that it would be in the national interest to join, but they have all pledged to abide by the result of the referendum. Former Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt stated in December 2007 that there will be no referendum until there is stable support in the polls.[140] The polls have generally showed stable support for the "no" alternative, except some polls in 2009 showing a support for "yes". Since 2010 the polls have shown strong support for "no" again. According to a eurobarometer poll in April 2015, 32 per cent of Swedes are in favour of introducing the euro (an increase of 9 per cent from November 2014), whereas 66 per cent are opposed (a decrease of 7 per cent from November 2014).[118][141]

Outside the EU

The EU's position is that no independent sovereign state is allowed to join the eurozone without first being a full member of the European Union (EU). However, four independent sovereign European microstates situated within the borders of the eurozone states, have such a small size — rendering them unlikely ever to join the EU — that they have been allowed to adopt the euro through the signing of monetary agreements, which granted them rights to mint local euro coins without gaining a seat in the European Central Bank. In addition, some dependent territories of EU member states have also been allowed to use the euro without being part of the EU, conditional the signing of agreements where a eurozone state guarantee their prior adoption of regulations applying specifically for the eurozone.

Current adopters

European microstates

| State | Adopted euro | Notes | Pop. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January 2002 (de facto)[143] 1 April 2012 (de jure)[52] |

Issuing rights: 1 July 2013 | 82,000 | |

| 1 January 1999 | Issuing rights: 1 January 2002 | 32,671 | |

| 1 January 1999 | Issuing rights: 1 January 2002 | 29,615 | |

| 1 January 1999 | Issuing rights: 1 January 2002 | 800 | |

| 1 January 2002[154] (unilateral adoption) |

Potential Candidate Seeking EU Membership[155] |

1,700,000 | |

| 1 January 2002[156] (unilateral adoption) |

Candidate Seeking EU Membership[157] |

684,736 |

The European microstates of Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City, which had a monetary agreement with a eurozone state when the euro was introduced, were granted a special permission to continue these agreements and to issue separate euro coins, but they don't get any input or observer status in the economic affairs of the eurozone. Andorra, which had used the euro unilaterally since the inception of the currency, negotiated a similar agreement which granted them the right to officially use the euro as of 1 April 2012 and to issue euro coins.[52]

Kosovo and Montenegro

Kosovo[lower-alpha 1] and Montenegro have unilaterally adopted and used the euro since its launch, as they previously used the German mark rather than the Yugoslav dinar. This was due to political concerns that Serbia would use the currency to destabilise these provinces (Montenegro was then in a union with Serbia) so they received Western help in adopting and using the mark (though there was no restriction on the use of the dinar or any other currency). They switched to the euro when the mark was replaced, but have signed no monetary agreement with the ECB; rather the country depends only on euros already in circulation.[158][159] Kosovo also still uses the Serbian dinar, which replaced the Yugoslav dinar, in areas mainly populated by the Serbian minority.[160]

Potential adopters

Iceland

During the 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis, instability in the króna led to discussion in Iceland about adopting the euro. However, Jürgen Stark, a Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, has stated that "Iceland would not be able to adopt the EU currency without first becoming a member of the EU".[161] Iceland subsequently applied for EU membership. As of the ECB's May 2012 convergence report, Iceland did not meet any of the convergence criteria.[162] One year later, the country had achieved compliance with the deficit criteria and had begun to decrease its debt-to-GDP ratio,[163] but still suffered from elevated HICP inflation and long-term governmental interest rates. On 13 September 2013, a newly elected government dissolved the accession negotiation team and thus suspended Iceland's application to join the European Union until a referendum can be held on whether or not the accession negotiations should resume; if negotiations do resume, after they are completed the public will then have the opportunity in a second referendum to vote on "whether or not Iceland shall join the EU on the negotiated terms".[164][165][166]

Dutch overseas territories

| Territory | ISO 3166-1 code | ISO 4217 code | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| AW | AWG | Aruba is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but not the EU. It uses the Aruban florin, which is pegged to the US dollar.(1 dollar = 1.79 florins) | |

| CW | ANG | Currently uses the Netherlands Antillean guilder and had planned to introduce the Caribbean guilder in 2014, although the change has been delayed. Both are pegged to the US dollar.(1 dollar = 1.79 guilder)[167] | |

| SX | ANG | Currently uses the Netherlands Antillean guilder and had planned to introduce the Caribbean guilder in 2014, although the change has been delayed. Both are pegged to the US dollar.(1 dollar = 1.79 guilder)[167] | |

| BQ | USD | Uses the US Dollar. |

Danish overseas territories

The Danish krone is currently used by both of its dependent territories, Greenland and Faroe Islands, with their monetary policy controlled by the Danish Central Bank.[168] If Denmark does adopt the euro, separate referendums would be required in both territories to decide whether they should follow suit. Both territories have voted not to be a part of the EU in the past, and their populations will not participate in the Danish euro referendum.[169] The Faroe Islands use a special version of the Danish krone notes that have been printed with text in the Faroese language.[170] It is regarded as a foreign currency, but can be exchanged 1:1 with the Danish version.[168][170] On 5 November 2009 the Faroese Parliament approved a proposal to investigate the possibility for euro adoption, including an evaluation of the legal and economic impact of adopting the euro ahead of Denmark.[171][172][173][174]

French overseas territories

The CFP franc is currently used as a euro pegged currency by three French overseas collectivities: French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna and New Caledonia. The French government has recommended that all three territories decide in favour of adopting the euro. French Polynesia has declared themselves in favour of joining the eurozone. Wallis and Futuna announced a neutral standpoint, that they would support a currency choice similar to what New Caledonia chooses. However, New Caledonia has not yet made any decision, because they first await the fallout of an independence referendum, scheduled to be held at the latest in November 2018,[lower-alpha 2] as this might influence their opinion whether or not to adopt the euro. If the three collectivities decide to adopt the euro, the French government would make an application on their behalf to the European Council, and the switch to the euro could be made after a couple of years. If the collectivities fail to reach a unanimous decision about the future of the CFP franc, it would be technically possible to implement an individual currency decision for each territory.[176]

Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus is legally part of the EU, but law is suspended due to north being under the control of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which the EU does not recognise. The North uses the Turkish lira instead of the euro, although the euro circulates alongside the lira and other currencies. On the resolution of the Cyprus dispute and the reunification of the island, the euro would become the official currency of the north also as part of the South's membership.[177]

See also

- Enlargement of the European Union

- History of the European Union

Notes

- Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 97 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 112 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition.

- According to the Nouméa Accord, the Congress of New Caledonia is entitled to schedule an independence referendum during 2014–18, if a ⅔ majority for this exist in the Congress. If the Congress refrain to call the referendum during 2014–18, the French state will call for it to take place in November 2018. Should the electorate vote "yes" to full independence, then the territory will change status from its current OCT status to become a fully sovereign state. Should the electorate vote "no" to full independence, then a second independence referendum will be called two years later, asking if the electorate is certain about their choice. If the electorate confirm their "no vote" in the second independence referendum, another third one will be called two years later, asking if the electorate is absolutely sure. If the "no vote" will be confirmed again, this settle the question, meaning that New Caledonia will maintain its current autonomy powers while continuing being a dependent OCT associated with France. In theory, the territory also have the third option "to become an integrated part of France as an Outermost region (OMR status)" — which automatically also would make it an integrated part of EU and the Eurozone — but this is not under consideration by any of the established political parties on the island, and thus not an option the electorate can vote for in the independence referendum.[175]

- A particular high uncertainty exists for the Polish selection of HICP outliers, as it is only based upon evaluation of the first part of the official outlier criteria. The official outlier criteria require both (1) The HICP rate to be significantly below the eurozone average and (2) This "significant below" HICP to stem from adverse price developments from exceptional factors (i.e. severe enforced wage cuts, exceptional developments in energy/food/currency markets, or a strong recession). Precedent assessment cases proof the second part of the outlier criteria also needs to be met, i.e. Finland had a HICP criteria value being 1.7% below eurozone average in August 2004 without being classified to be "HICP outlier" by the European Commission,[30] and Sweden likewise had a HICP criteria value being 1.4% below eurozone average in April 2013 without being classified to be "HICP outlier" by the European Commission.[31]

In addition to the uncertainty related to the fact that the Polish source only evaluate the first requirement, there is also uncertainty related to the Polish quantification of what "significant below" means. For all assessment months until March 2014, the Polish source had adopted the assumption (based on precedent assessment cases) that "all states with HICP criteria values minimum 1.8% below eurozone average" should be classified to be "HICP outliers". Based on the 2014 EC Convergence report's classification of Cyprus with a HICP criteria value only 1.4% below eurozone average as a "HICP outlier", the Polish source accordingly also adjusted their "HICP outlier selection criteria" from April 2014 onwards, so that it now automatically classify "all states with HICP criteria values minimum 1.4% below eurozone average" as "HICP outliers".[32] The European Commission never quantified what "significant below" means, which is why the Polish source attempts to quantify it based on precedent assessment cases, but this also means it is uncertain whether or not the currently assumed 1.4% limit is correct. It could perhaps just as well be 1.0%. - Cite from the 2014 Polish convergence report: Due to the significant reform agenda in the European Union and in the euro area, the current objective is to update the National Euro Changeover Plan with reference to the impact of those changes on Poland's euro adoption strategy. The date of completion of the document is conditional on the adoption of binding solutions on the EU forum concerning the key institutional changes, in particular, those referring to the banking union. The outcome of these changes determines the area of the necessary institutional and legal adjustments as well as the national balance of costs and benefits arising from introduction of the common currency.[49]

Cite from the 2015 Polish convergence report: Taking into account the scale of institutional changes in the European Union and the euro area, it was deemed proper to update the "National Euro Changeover Plan" as regards the consequences of these changes for the preparation strategy. The outcome of these changes determines the area of the necessary institutional and legal adjustments as well as the national balance of costs and benefits arising from introduction of the common currency. The date of completion of works on the update of the "Plan" depends on the completion of the main works on the institutional reform of the Economic and Monetary Union.[50] - As of January 2015, Bulgaria is not officially part of ERM II.[36] The Bulgarian National Bank pursues its primary objective of price stability through an exchange rate anchor in the context of a Currency Board Arrangement (CBA), obliging them to exchange monetary liabilities and euro at the official exchange rate 1.95583 BGN/EUR without any limit. The CBA was introduced on 1 July 1997 as a 1:1 peg against German mark, and the peg subsequently changed to euro on 1 January 1999.[55]

- Sweden, while obliged to adopt the euro under its Treaty of Accession, has chosen to deliberately fail to meet the convergence criteria for euro adoption by not joining ERM II without prior approval by a referendum.

References

- Kubosova, Lucia (5 May 2008). "Slovakia confirmed as ready for Euro". euobserver.com. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- "Ministers offer Estonia entry to eurozone January 1". France24.com. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Latvia becomes the 18th Member State to adopt the euro". European Commission. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- "POLICY POSITION OF THE GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK ON EXCHANGE RATE ISSUES RELATING TO THE ACCEDING COUNTRIES" (PDF). European Central Bank. 18 December 2003. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- "REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION – CONVERGENCE REPORT 2002 SWEDEN". European Commission. 22 May 2002. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- "New EU members to break free from euro duty". Euractiv.com. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- "Czech PM mulls euro referendum". EUobserver. 28 October 2011.

- "Czechs deeply divided on EU's fiscal union". Radio Praha. 19 January 2012.

- "ForMin: Euro referendum casts doubt on Czech pledges to EU". Prague Daily Monitor. 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- "Poland may get referendum on euro". BBC. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "L. Kaczyński: najpierw referendum, potem euro". 31 October 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- Cienski, Jan (26 March 2013). "Poland opens way to euro referendum". Financial Times. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Politics derail Poland's quest for the euro". Deutsche Welle. 26 August 2015.

- Vintilă, Carmen (2 June 2015). "Victor Ponta: Un referendum, înainte de a intra efectiv în zona euro, ar fi o măsură democratică". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "The acceding countries' strategies towards ERM II and the adoption of the euro: an analytical review" (PDF). ECB. February 2004. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "The corrective arm/ Excessive Deficit Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- "General government gross debt (EDP concept), consolidated - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report 2018". European Central Bank. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Convergence Report - May 208". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Convergence Report 2004" (PDF). European Commission. 20 October 2004. Retrieved 19 August 2005.

- "Convergence Report 2013" (PDF). European Commission. 3 June 2013.

- "Nominal Convergence Monitor April 2014 (Monitor konwergencji nominalnej kwietniu 2014)" (PDF) (in Polish). Ministry of Finance (Poland). 4 July 2014.

- "Release Calendar for Euro Indicators". Eurostat. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Convergence Report (May 2012)" (PDF). ECB. May 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- "Convergence Report 2014" (PDF). European Commission. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Exchange rate statistics: August 2015" (PDF). Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II. Deutsche Bundesbank. 14 August 2015.

- Bulgaria agrees to conditions for joining euro, Financial Times 12 July 2018

- "Adopting the euro: Scenarios for adopting the euro". 20 March 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Preparing the introduction of the euro – a short handbook" (PDF). European Commission. 15 April 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Unofficial consolidated text: Guideline of the ECB of 19 June 2008 amending Guideline ECB/2006/9 on certain preparations for the euro cash changeover and on frontloading and sub-frontloading of euro banknotes and coins outside the euro area (ECB/2008/4)(OJ L 176)" (PDF). ECB. 5 July 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Fifteenth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area" (PDF). European Commission. 21 November 2014.

- "Scenarios for adopting the euro". ec.europa.eu/. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- "A Coordinating Council on Bulgaria's membership in the euro area" (in Bulgarian). Bulgarian Government. 1 July 2015.

- "Agreement between the Council of Ministers and the Bulgarian National Bank on the introduction of the Euro in the Republic of Bulgaria" (PDF). Bulgarian National Bank. 26 November 2004.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Overgang til euro ved dansk deltagelse" (PDF). Økonomiministeriet. 14 June 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- "Illustration af danske euromønter". eu-oplysningen.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- "National Changeover Plan for Hungary: first update December 2009" (PDF). Magyar Nemzeti Bank (National Euro Co-ordination Committee). 7 January 2010.

- "Convergence programme: 2014 update" (PDF). Republic of Poland. April 2014.

- "Convergence Programme: 2015 update". Polish Ministry of Finance. 20 May 2015.

- "Guvernanţi: România poate adopta euro în 2015" (in Romanian). Evenimentul Zilei. 29 April 2011.

- "The euro outside the euro area". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- "Lithuanian PM keen on fast-track euro idea". London South East. 7 April 2007.

- "Fixed Euro conversion rates". European Central Bank. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- "EUROPEAN ECONOMY 4/2014: Convergence Report 2014" (PDF). European Commission. 4 June 2014.

- Bulgaria delays entry into euro ‘waiting room’ until July, EURACTIV 21 February 2020

- Eurobarometer November 2018

- Ilic, Igor (30 October 2017). "Croatia wants to adopt euro within 7-8 years: prime minister". Reuters. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Czech election stalemate on joining euro, EUObserver 13 October 2017

- "Regeringsgrundlag juni 2015: Sammen for Fremtiden (Government manifest June 2015: Together for the Future)" (PDF) (in Danish). Venstre. 27 June 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2015.

- "Orbán: Hungary will not adopt the euro for many decades to come". Hungarian Free Press. 3 June 2015.

- Poland's new government not in hurry to join euro - finance minister, Reuters 19 January 2016

- "Romania's 2024 euro adoption goal 'very ambitious': FinMin". CNBC. 27 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Erika Svantesson (9 May 2009). "Alliansen splittrad i eurofrågan" [Alliance fragmented over euro question]. DN.se (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter AB. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Commission. May 2012.

- "Convergence Report June 2013" (PDF). European Commission. June 2013.

- "Convergence Report June 2014" (PDF). European Commission. June 2014.

- "Joining Euro to Have Positive Impact on Bulgaria's Economy - Experts". Sofia News Agency (Novinite). 19 January 2015.

- "Bulgaria puts off Eurozone membership for 2015". Radio Bulgaria. 26 July 2011. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- "Bulgaria Sees Euro Recovery to Boost Growth Quickly, Kostov Says". Bloomberg. 15 January 2014.

- "Bulgaria says it will start talks to join the euro". 16 January 2015.

- "Bulgaria creates council for preparation for euro zone membership". The Sofia Globe. 1 July 2015.

- "GERB leader Borissov: Bulgaria will apply to join euro zone". Sofia Globe. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "Bulgaria to know its chances for ERM II accession by end-2017". Central European Financial Observer. 3 July 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- Bulgaria to take first steps towards euro, EUOBSERVER 11 January 2018

- Bulgaria expects to apply for eurozone waiting room by July, EURACTIV 11 January 2018

- UPDATE 2-Defiant Bulgaria to push for ERM-2 membership Retuers 11 January 2018

- Bulgaria renews calls for euro as it takes on EU presidency, Euronews 11 January 2018

- "Letter by Bulgaria on ERM II participation" (PDF). 29 June 2018.

- "Statement on Bulgaria's path towards ERM II participation". Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- THOMSON, AINSLEY. "Croatia Aims for Speedy Adoption of Euro". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- "Konferencija HNB-a u Dubrovniku: Hrvatska može uvesti euro najranije 2019" (in Croatian). HNB. 14 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

- "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "Deficit to fall below 3 pct of GDP, public debt to stop rising by 2017". Government of the Republic of Croatia. 30 April 2015.

- Ilic, Igor (30 October 2017). "Croatia wants to adopt euro within 7-8 years: prime minister". Reuters. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "Croatia Could Enter ERM II in Second Half of 2020". Total Croatia news. 23 November 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Topolánek a Tůma: euro v roce 2010 v ČR nebude". Novinky.cz (in Czech). 19 September 2006. Archived from the original on 6 May 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "Czechs, Poles cooler to euro as they watch debt crisis". Reuters. 16 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Pop, Valentina (28 October 2011). "Czech PM mulls euro referendum". EUObserver. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

"The conditions under which the Czech citizens decided in a referendum in 2003 on the country's accession to the EU and on its commitment to adopt the single currency, euro, have changed. That is why the ODS will demand that a possible accession to the single currency and the entry into the European stabilisation mechanism be decided on by Czech citizens," the ODS resolution says.

- Bilefsky, Dan (1 March 2013). "Czechs Split Deeply Over Joining the Euro". The New York Times.

- "Skeptical Czechs may be pushed to change tone on euro". Reuters. 26 April 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- "CNB and MoF recommend not to set euro adoption date yet". Czech National Bank. 18 December 2013. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "Czech government sets target of agreeing euro adoption process by 2020". IntelliNews. 28 April 2015.

- "Babiš odhalil program: odmítá euro, chce zavření evropské hranice (The new prime minister revealed his programme: he rejects Euro and wants to close European borders)" (in Czech). Lidovky.cz. 11 January 2018.

- Stratton, Allegra (22 November 2007). "Danes to hold referendum on relationship with EU". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- Brand, Constant (13 October 2011). "Denmark scraps border-control plans". European Voice. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "Debt Crisis Pushes Danish Euro Opposition to Record, Poll Shows". Bloomberg. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "Greens Analyseinstitut" (PDF). Børsen (Greens Analyseinstitut). 7 May 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2013.

- "Orbán: We won't have euro until 2020.(In Hungarian.)". Index. 5 February 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "Matolcsy: Hungarian euro is possible in 2020" (in Hungarian). Világgazdaság. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "European Economic Forecast Spring 2015 - 17.Hungary" (PDF). European Commission. 5 May 2015.

- "Orbán: Hungary will keep forint until its GDP reaches 90% of eurozone average". All Hungary Media Group. 26 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Hungary election: PM Viktor Orban declares victory". BBC. 6 April 2014.

- "Hungary's New Notes Speak of Late Conversion to Euro". The Wall Street Journal. 1 September 2014.

- "Orbán: Hungary will not adopt the euro for many decades to come". Hungarian Free Press. 3 June 2015.

- "HUNGARY'S ECONOMY MINISTER SEES POSSIBILITY FOR ADOPTING EURO BY 2020 – UPDATE". Daily News Hungary. 3 June 2015.

- "Hungary mulls euro adoption by 2020". BR-epaper. 19 July 2016.

- Top Banker Says Hungary May Adopt the Euro Sooner Than Expected Bloomberg 5 October 2017

- "Poland president says no euro entry decision before 2015 ballots". Reuters. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Puhl, Jan (6 February 2013). "Core or Periphery?: Poland's Battle Over Embracing the Euro". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- "Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2nd April 1997, as published in Dziennik Ustaw (Journal of Laws) No. 78, item 483". Parliament of the Republic of Poland. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Monetary policy guidelines for 2013 (print nr.764)" (PDF). The Monetary Policy Council of the Polish National Bank (page 9) (in Polish). Sejm. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "Polish opposition calls for single currency referendum". Polskie Radio. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Cienski, Jan (26 March 2013). "Poland opens way to euro referendum". Financial Times. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- Euro push in Poland pitched as peace offering with EU, Politico 4 January 2018

- "As much as 58% of Poles are against the euro" (in Polish). Forbes.pl. 5 June 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- "April 2014 Eurobarometer poll"

- "April 2015 Eurobarometer poll"

- "As much as 58% of Poles are against the euro" (in Polish). Forbes.pl. 5 June 2012.

- "TNS Poland: 49 per cent respondents in favor of the euro, 40 per cent against (TNS Polska: 49 proc. badanych za przyjęciem euro, 40 proc. przeciw)" (in Polish). Onet.business. 27 September 2013.

- "TNS: 45 per cent respondents in favor of the euro, 40 per cent against (TNS OBOP: 45 proc. badanych za przyjęciem euro, 40 proc. przeciw)" (in Polish). Parkiet. 17 December 2013. Archived from the original on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "Poles do not want the euro. 63% of respondents fear the adoption of the euro (Polacy nie chcą euro. 63% badanych obawia się przyjęcia europejskiej waluty)" (in Polish). Wpolityce.pl. 25 March 2014.

- "TNS: 46 per cent Poles for adoption of the euro; 42 per cent against (TNS: 46 proc. Polaków za przyjęciem euro; 42 proc. przeciw)" (in Polish). Puls Biznesu. 2 July 2014.

- "TNS Polska: Odsetek osób oceniających wejście do euro za błąd wzrósł do 51 proc" (in Polish). Obserwator Finansowy. 25 September 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2014.

- "TNS Poland: 49 per cent for, 40 per cent against the introduction of the euro in Poland (TNS Polska: 49 proc. za, 40 proc. przeciwko wprowadzeniu w Polsce euro)" (in Polish). Interia.pl. 21 December 2014.

- "Attitudes to adopt the euro without major changes, dominated by skeptics (Nastawienie do przyjęcia euro bez większych zmian, dominują sceptycy)" (in Polish). Bankier.pl. 25 March 2015.

- "Poles are increasingly skeptic against the euro (Polacy coraz sceptyczniejsi wobec euro" (in Polish). EurActiv. 24 June 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- "Isarescu: Trecem la euro dupa 2012" (in Romanian). 18 May 2006. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "Government of Romania: 2012–15 Convergence Programme" (PDF). European Commission. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Trotman, Andrew (18 April 2013). "Romania abandons target date for joining euro". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- "Isarescu: Romania needs law to enforce 2019 Euro-adoption target". Business Review. 19 August 2014.

- "Government of Romania Convergence Programme 2015-2018" (PDF). Government of Romania. April 2015.

- "Purchasing power parities (PPPs), price level indices and real expenditures for ESA2010 aggregates: GDP Volume indices of real expenditure per capita in PPS (EU28=100)". Eurostat. 16 June 2015.

- "Central Bank: Romania 2019 euro membership 'not feasible'". EUObserver. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- "Romania may join euro zone in 2022, says foreign minister - report". CNBC. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- "Romania's ruling party congress votes to join euro in 2024". Reuters. 10 March 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Sverige sa nej till euron" (in Swedish). Swedish Parliament. 28 August 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- "Information on ERM II". European Commission. 22 December 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- "Folkomröstning 14 september 2003 om införande av euron" (in Swedish). Swedish Election Authority. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- "Glöm euron, Reinfeldt" (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. 2 December 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- "Public Opinion in the European Union" (PDF). 1 November 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- "Monetary Agreement between the European Union and the Principality of Andorra". Official Journal of the European Union. 17 December 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Between 1 January 2002, when the euro was launched, and 1 April 2012, when their Monetary Agreement with the EU came into force, Andorra did not have an official currency but used the euro as their de facto currency.

- "Council Decision of 31 December 1998 on the position to be taken by the Community regarding an agreement concerning the monetary relations with the Principality of Monaco". Official Journal of the European Communities. 4 February 1999. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Monetary agreement between the Government of the French Republic, on behalf of the European Community, and the Government of his Serene Highness the Prince of Monaco". Official Journal of the European Union. 31 May 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Commission Decision of 28 November 2011 on the conclusion, on behalf of the European Union of the Monetary Agreement between the European Union and the Principality of Monaco". Official Journal of the European Union. 28 January 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Council Decision of 31 December 1998 on the position to be taken by the Community regarding an agreement concerning the monetary relations with the Republic of San Marino". Official Journal of the European Communities. 4 February 1999. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Monetary agreement between Italian, on behalf of the European Community, and the Republic of San Marino". Official Journal of the European Union. 27 July 2001. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Monetary Agreement between the European Union and the Republic of San Marino". Official Journal of the European Union. 26 April 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Council Decision of 31 December 1998 on the position to be taken by the Community regarding an agreement concerning the monetary relations with Vatican City". Official Journal of the European Communities. 4 February 1999. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Monetary agreement between the Italian Republic, on behalf of the European Community, and the Vatican City State and, on its behalf, the Holy See". Official Journal of the European Union. 25 October 2001. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Monetary Agreement between the European Union and the Vatican City State". Official Journal of the European Union. 4 February 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Administrative Direction No. 1999/2". UNMIK. 4 October 1999. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011.

- The Deutsche Mark was declared by UNMIK as legal tender in Kosovo on 4 October 1999.[153] When Germany yielded the Deutsche Mark for the Euro on 1 January 2002, this also happened in Kosovo. Subsequently the Republic of Kosovo unilaterally adopted the Euro as its official currency.

- "Enlargement – Kosovo". European Commission. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Montenegro abandon the use of the Yugoslav dinar in November 1999. Since then, the Deutsche Mark was used as legal tender. When Germany yielded the Deutsche Mark for the Euro on 1 January 2002, Montenegro unilaterally adopted the Euro as its official currency.

- "Enlargement – Montenegro". European Commission. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Euro used as legal tender in non-EU nations – Business – International Herald Tribune – The New York Times". International Herald Tribune. 1 January 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- "Kouchner Signs Regulation on Foreign Currency" (Press release). 2 September 1999. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- "European Commission – Enlargement – Kosovo – Economic profile – Enlargement". European Commission. 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- "Iceland cannot adopt the Euro without joining EU, says Stark". IceNews. 23 February 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Central Bank. May 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "European economic forecast – Winter 2013" (PDF). European Commission. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Pop, Valentina (13 September 2013). "Iceland dissolves EU accession team". EU Observer. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014.

- Nielsen, Nikolaj (22 May 2013). "Iceland leader snubs EU membership". EU Observer. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013.

- "Stjórnarsáttmáli kynntur á Laugarvatni". 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Document A: Presentation by Bodil Nyboe Andersen "Økonomien i rigsfællesskabet"" (PDF) (in Danish). Føroyskt Løgting. 25 May 2004. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "Use of Euro in Affiliated Countries and Territories Outside the EU" (PDF). Danmarks Nationalbank. 30 June 2000. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "The Faroese banknote series". Danmarks Nationalbank. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "Løgtingsmál nr. 11/2009: Uppskot til samtyktar um at taka upp samráðingar um treytir fyri evru sum føroyskt gjaldoyra" (PDF) (in Faroese). 4 August 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Rich Faroe Islands may adopt euro". Fishupdate.com. 12 August 2009. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Euro wanted as currency in Faroe Islands". Icenews.is. 8 August 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "11/2009: Uppskot consenting to undertake conversations of trust for introducing euro as a Faroese currency (second reading)" (in Faroese). Føroyskt Løgting. 5 November 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "Nouvelle-Calédonie: "On a ouvert un processus de décolonisation par étapes" (New Caledonia: "A staged decolonization process has begun")" (in French). Le Monde. 13 May 2014.

- "Nouvelle-Calédonie : Entre Émancipation, Passage A L'Euro Et Recherche De Ressources Nouvelles" (PDF). 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Euro adoption northern Cyprus Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, inCyprus 18 May 2016

- http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/index#p=1&instruments=STANDARD&yearFrom=1999&yearTo=2017