Elizabeth Báthory

Countess Elizabeth Báthory de Ecsed (Hungarian: Báthory Erzsébet, pronounced [ˈbaːtori ˈɛrʒeːbɛt]; Slovak: Alžbeta Bátoriová ; 7 August 1560 – 21 August 1614)[1] was a Hungarian noblewoman from the noble family of Báthory, who owned land in the Kingdom of Hungary (now Hungary, Slovakia and Romania).

Elizabeth Báthory | |

|---|---|

Copy of the lost 1585 original portrait of Elizabeth Báthory | |

| Born | Erzsébet Báthory 7 August 1560 Nyírbátor, Kingdom of Hungary |

| Died | 21 August 1614 (aged 54) Csejthe, Kingdom of Hungary (now Čachtice, Slovakia) |

| Other names | Nádasdy Ferencné Báthori Erzsébet |

| Spouse(s) | Ferenc Nádasdy |

| Children | Paul Anna Ursula Katherine |

| Criminal penalty | Confinement until death |

| Details | |

| Victims | More than 650 people |

Span of crimes | 1590–1610 |

| Country | Kingdom of Hungary |

Date apprehended | 30 December 1610 |

.svg.png)

Báthory has been labeled by Guinness World Records as the most prolific female murderer,[2] though the precise number of her victims is debated. Báthory and four collaborators were accused of torturing and killing hundreds of young women between 1590 and 1610.[3] There is no hard evidence about the whole murder case.[4] The highest number of victims cited during Báthory's trial was 650. However, this number comes from the claim by a servant girl named Susannah that Jakab Szilvássy, Báthory's court official, had seen the figure in one of Báthory's private books. The book was never revealed, and Szilvássy never mentioned it in his testimony.[5] Despite the evidence against Báthory, her family's importance kept her from facing execution. She was imprisoned in December 1610 within Castle of Csejte, in Upper Hungary (now Slovakia).

The stories of Báthory's sadistic serial murders are verified by the testimony of more than 300 witnesses and survivors as well as physical evidence and the presence of horribly mutilated dead, dying and imprisoned girls found at the time of her arrest.[6] Stories describing Báthory's vampiric tendencies, such as the tale that she bathed in the blood of virgins to retain her youth, were generally recorded years after her death, and are considered unreliable. Her story quickly became part of national folklore, and her infamy persists to this day.[7] She is often compared to Vlad the Impaler of Wallachia (on whom the fictional Count Dracula is partly based); some insist she inspired Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897),[8] though there is no evidence to support this hypothesis.[9] Nicknames and literary epithets attributed to her include The Blood Countess and Countess Dracula.

Early years

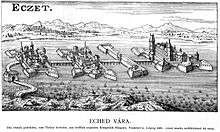

Elizabeth Báthory was born on her family's estate in Nyírbátor, Kingdom of Hungary on August 7, 1560.[10] She lived at her family’s palatial castle in Ecsed until she was 11.[11]

Elizabeth’s family was extraordinarily wealthy and politically powerful during her lifetime. She was related by blood and marriage to many of the most powerful men in 16th-century Hungary, Transylvania, Croatia, Poland, and the Holy Roman Empire.

- Her grandfather, Stephen VIII Báthory, was royal count palatine and commander of the king’s military during the disastrous Battle of Mohács.[12][13]

- Elizabeth’s uncle, Stephen IX Báthory, was voivode of Transylvania (1571-1576) and then ascended to Prince of Transylvania, King of Poland, and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576-1586).[14]

- Stephen’s nephew and successor to Transylvania, Sigismund Báthory, was Elizabeth’s cousin.[14]

- Another cousin, Cardinal Andrew Báthory, was briefly Prince of Transylvania in 1599.[14]

- Elizabeth was related by marriage to the next prince of Transylvania and (disputed) prince of Hungary, Stephen Bocskay.[14]

- Bocskay’s successor and heir to the princedom of Transylvania was Gabriel Báthory, Elizabeth’s first cousin.[14]

Báthory was raised a Calvinist Protestant. As a young woman, she learned Latin, German, Hungarian, and Greek.[3][15][16] Born into a privileged family of nobility, Báthory was endowed with wealth, education, and a stellar social position.

Married life

When Báthory was 12, her mother arranged her marriage to Francis Nádasdy, the heir to the massive Nádasdy-Kaniszai fortune.[17] (Potentially-reliable records indicate that Elizabeth Báthory’s father, George VI Báthory di Ecsed, died in 1570.[14] Therefore, only Elizabeth’s mother, Anna Báthory di Somlyo, would have been alive in 1572 to arrange the marriage.) Elizabeth and Francis married on May 8, 1575, a couple months before Elizabeth’s 15th birthday.[18] The ceremony, an extraordinarily lavish wedding with 4,500 guests, took place in Varannó (today Vranov nad Topľou, Slovakia),[19] and the Holy Roman Emperor himself sent the couple a congratulatory letter and a wedding gift.[20]

During her lifetime, Elizabeth assumed both the names Báthory and Nádasdy. After Báthory married, she still signed most of her letters with her maiden name: Elizabeta Comitissa [sic] de Báthory.[21] Even when Count Francis Nádasdy co-signed a letter or decree with her, she used her maiden name.[22] During her accusation and imprisonment, however, her sons-in-law and the royal count palatine referred to her as “Lady Nádasdy” and “Widow Nádasdy.”[23]

Nádasdy's wedding gift to Báthory was the Castle of Csejte, situated in the Little Carpathians.[24] The gift also included the Csejte country house and seventeen adjacent villages.[24]

After 10 years of childlessness, Elizabeth Báthory bore her first child, Anna Nadasdy, in 1585.[10] Katalin Nadasdy was probably born in 1594, and Báthory's only living son, Paul Nadasdy, was born in 1598. Elizabeth hired governesses to care for all of her children, as was standard for early modern Eastern European nobility.[25][26]

During the Long Turkish War (1593-1606)

In 1578, Nádasdy became the chief commander of Hungarian troops, leading them to war against the Ottomans.[27] With her husband away at war, Báthory managed business affairs and the estates.[28]

While Nadasdy led Hungarian forces during the Long War (1593-1606), Báthory handled the defense of her estates, which lay on the route to Vienna.[15] The threat was significant, for the village of Csejte had previously been plundered by the Ottomans while Sárvár, located near the border that divided Royal Hungary and Ottoman-occupied Hungary, was in even greater danger. There were several instances where Báthory intervened on behalf of destitute women, including a woman whose husband was captured by the Ottomans and a woman whose daughter was raped and impregnated.[28]

Ferenc Nádasdy died on 4 January 1604 at the age of 48. Although the exact nature of the illness which led to his death is unknown, it seems to have started in 1601, and initially caused debilitating pain in his legs. From that time, he never fully recovered, and in 1603 became permanently disabled.[29] He had been married to Báthory for 29 years. Before dying, Nádasdy entrusted his heirs and widow to György Thurzó, who would eventually lead the investigation into Báthory's crimes.[30]

Accusation

Investigation

Between 1602 and 1604, after rumours of Báthory's atrocities had spread through the kingdom, Lutheran minister István Magyari made complaints against her, both publicly and at the court in Vienna.[31] The Hungarian authorities took some time to respond to Magyari's complaints. Finally, in 1610, King Matthias II assigned Thurzó, the Palatine of Hungary, to investigate. Thurzó ordered two notaries to collect evidence in March 1610.[32] In 1610 and 1611, the notaries collected testimony from more than 300 witnesses.

According to the testimonies, Báthory's initial victims were servant girls aged 10 to 14 years;[33] the daughters of local peasants, many of whom were lured to Csejte by offers of well paid work as maids; and servants in the castle. Later, Báthory is said to have begun killing daughters of the lesser gentry, who were sent to her gynaeceum by their parents to learn courtly etiquette. Abductions were said to have occurred as well.[34] The atrocities described most consistently included severe beatings; burning or mutilation of hands; biting the flesh off the faces, arms and other body parts; freezing or starving to death.[34] The use of needles was also mentioned by the collaborators in court. There were many suspected forms of torture carried out by Báthory.[35] According to the Budapest City Archives, the girls were burned with hot tongs and then placed in freezing cold water.[35] They were also covered in honey and live ants.[35] Báthory was also suspected of cannibalism.[35]

Some witnesses named relatives who died while at the gynaeceum. Others reported having seen traces of torture on dead bodies, some of which were buried in graveyards, and others in unmarked locations. Two court officials (Benedek Deseő and Jakab Szilvássy) claimed to have personally witnessed the Countess torture and kill young servant girls.[30]:96–99 According to the testimony of the defendants, Báthory tortured and killed her victims not only at Csejte but also on her properties in Sárvár, Németkeresztúr, Pozsony, Vienna, and elsewhere. It is an important fact, that Szilvásy's and Deseő's statement came half a year later than the arrest. These two persons were mentioned by the servants during the torture, so it is possible that they were also afraid of torture, if they didn't give the "right answer." [36]

Arrest

Thurzó went to Csejte Castle and arrested Báthory along with four of her servants, who were accused of being her accomplices: Dorotya Semtész, Ilona Jó, Katarína Benická, and János Újváry ("Ibis" or Fickó). Thurzó, and the soldiers found a living "prey" girl in the castle, but there is no evidence that they asked her what had happened to her. Although it is commonly believed that Báthory was caught in the act of torture, she was having dinner. Initially, Thurzó made the declaration to Báthory's guests and villagers that he had caught her red-handed. However, she was arrested and detained prior to the discovery or presentation of the victims. It seems most likely that the claim of Thurzó's discovering Báthory covered in blood has been the embellishment of fictionalized accounts.[37]

Thurzó debated further proceedings with Báthory's son Paul and two of her sons-in-law. A trial and execution would have caused a public scandal, an influential family which ruled Transylvania would be disgraced, and Elizabeth's considerable property would have been seized by the crown. Thurzó, along with Paul and her two sons-in-law, originally planned for Báthory to be spirited away to a nunnery, but as accounts of her murder of the daughters of lesser nobility spread, it was agreed that she would be kept under strict house arrest and that further punishment should be avoided.[38]

Most of the witnesses testified that they had heard the accusations from others, but didn't see it themselves. The servants confessed under torture, which is not credible in contemporary proceedings, either. They were the king's witnesses, but they were executed quickly. The accusations of murder were based on rumors. There is no document to prove that anyone in the area complained about the Countess. With so many missing girls, there should be at least one correspondence about it. In this time period, if someone was harmed, or someone even stole a chicken, a letter of complaint was written. There was no regular trial, and no court hearing against the person of Elizabeth Báthory. Two trials were held in the wake of Báthory's arrest: the first was held on 2 January 1611, and the second on 7 January 1611. [39]

Prison and death

On January 25, 1611, Thurzó wrote in a letter to Hungarian King Matthias regarding the capture of the accused Elizabeth Báthory and her confinement in the castle. The palatine also coordinated the steps of the investigation with the political struggle with the Prince of Transylvania. The widow was detained in the castle of Csejte for the rest of her life, where she died at the age of 54. As György Thurzó wrote, Elizabeth Báthory was locked in a bricked room, but according to other sources (written documents from the visit of priests, July 1614), she was able to move freely and unhindered in the castle, so today the bondage could be called house arrest. In the last month, she signed her arrangement, in which she distributed the estates, lands and possessions among her children.[40][41] On the evening of 20 August 1614, Báthory complained to her bodyguard that her hands were cold, whereupon he replied "It's nothing, mistress. Just go lie down." She went to sleep and was found dead the following morning.[42] She was buried in the church of Csejte on 25 November 1614,[42] but according to some sources due to the villagers' uproar over having the Countess buried in their cemetery, her body was moved to her birth home at Ecsed, where it was interred at the Báthory family crypt.[43] The location of her body today is unknown. The Csejte church or the castle of Csejte do not bear any markings of her possible grave.[44]

Reputation

Several authors such as László Nagy and Dr. Irma Szádeczky-Kardoss have argued that Elizabeth Báthory was a victim of a conspiracy.[45][46] Nagy argued that the proceedings against Báthory were largely politically motivated, possibly due to her extensive wealth and ownership of large areas of land in Hungary, escalating after the death of her husband. The theory is consistent with Hungarian history at that time, which included religious and political conflicts, especially relating to the wars with the Ottoman Empire, the spread of Protestantism and the extension of Habsburg power over Hungary.[47]

There are counter-arguments made against this theory. The investigation into Báthory's crimes was sparked by complaints from a Lutheran minister, István Magyari.[31] This does not contribute to the notion of a Catholic/Habsburg plot against the Protestant Báthory, although religious tension is still a possible source of conflict as Báthory was raised Calvinist, not Lutheran.[48] To support Báthory's innocence, the testimony of around 300 witnesses [30]:96–99 and the physical evidence collected by the investigators have to be addressed or disputed. That evidence included numerous bodies and dead and dying girls found when the castle was entered by Thurzó.[6] Szádeczky-Kardoss argues the physical evidence was exaggerated and Thurzó misrepresented dead and wounded patients as victims of Báthory, as disgracing her would greatly benefit his political state ambitions.[46]

Folklore and popular culture

The case of Elizabeth Báthory inspired numerous stories during the 18th and 19th centuries. The most common motif of these works was that of the countess bathing in her victims' blood to retain beauty or youth. This legend appeared in print for the first time in 1729, in the Jesuit scholar László Turóczi's Tragica Historia, the first written account of the Báthory case.[49] The story came into question in 1817, when the witness accounts (which had surfaced in 1765) were published for the first time. They included no references to blood baths.[50] In his book Hungary and Transylvania, published in 1850, John Paget describes the supposed origins of Báthory's blood-bathing, although his tale seems to be a fictionalized recitation of oral history from the area.[51] It is difficult to know how accurate his account of events is. Sadistic pleasure is considered a far more plausible motive for Elizabeth Báthory's crimes.[52]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Elizabeth Báthory[53][54] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Immoral Tales – 1973 portmanteau film; the third story is "Erzsébet Báthory"

- Bathory – 2008 historical drama written and directed by Juraj Jakubisko

- The Countess – 2009 drama historical movie written and directed by Julie Delpy

- Elizabeth Branch

- Elizabeth Brownrigg

- Delphine LaLaurie

- Catalina de los Ríos y Lisperguer

- Darya Nikolayevna Saltykova

- Mariam Soulakiotis

References

- "Elizabeth Bathory | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Most prolific female murderer". Guinness World Records. Guinness World Records Limited. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

The most prolific female murderer and the most prolific murderer of the western world, was Elizabeth Bathory, who practised vampirism on girls and young women. Described as the most vicious female serial killer of all time, the facts and fiction on the events that occurred behind the deaths of these young girls are blurred. Throughout the 15th century, she is alleged to have killed more than 600 virgins

- Ramsland, Katherine. "Lady of Blood: Countess Bathory". Crime Library. Turner Entertainment Networks Inc. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Bledsaw, Rachael Leigh (20 February 2014)

- Thorne, Tony (1997). Countess Dracula. London, England: Bloomsbury. p. 53. ISBN 978-1408833650.

- Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). p. 293. OCLC 654683776.

- "The Plain Story". Elizabethbathory.net. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- Joshi, S. T. (2011). Encyclopedia of the Vampire: The Living Dead in Myth, Legend, and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 6. ISBN 9780313378331. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- Stoker, Bram; Eighteen-Bisang, Robert; Miller, Elizabeth (2008). Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 131. ISBN 9780786477302. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- Craft, Kimberly L (2014). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsebet Bathory (2nd ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Craft, Kimberly L (2014). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsebet Bathory (2nd ed.). CreateSpace. p. 19.

- Molnár, Miklós (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge University Press. p. 87.

- "Battle of Mohacs 1526 - Ottoman Wars Documentary". YouTube: Kings & Generals. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Marek, Miroslav. "Genealogy: Bathori of Somlyo". Genealogy.eu. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Dennis Bathory-Kitsz (4 June 2009). "Báthory Erzsébet – Báthory Erzsébet: Short FAQ". Bathory.org. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- (Firm), Time Books. The most notorious serial killers : ruthless, twisted murderers whose crimes chilled the nation. ISBN 9781683300274. OCLC 982117998.

- Craft, Kimberly L (2014). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Bathory (2nd ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 34.

- Craft, Kimberly L (2014). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Bathory (2nd ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 39.

- Craft, Kimberly L (2014). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Bathory (2nd ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 39.

- Craft, Kimberly L (2014). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Bathory (2nd ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 40.

- Craft, Kimberly L. The Private Letters of Countess Erzsébet Bathory. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 34.

- Craft, Kimberly L. The Private Letters of Countess Erzsébet Bathory. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 22, 25, 29.

- Craft, Kimberly L (2014). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Bathory (2nd ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 215, 224.

- Craft, Kimberley L. (2009). Infamous Lady:The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 34.

- Craft, Kimberley L. (2009). Infamous Lady:The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 51.

- "Biography of Erzsébet Bathory of Transylvania (±1561–1614), "The Blood Countess"". madmonarchs.guusbeltman.nl.

- Craft, Kimberley L. (2009). Infamous Lady:The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 39.

- Craft, Kimberley L. (2009). Infamous Lady:The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 38.

- Craft, Kimberley L. (2009). Infamous Lady:The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 69–70.

- Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). pp. 234–237. OCLC 654683776.

- Letters from Thurzó to both men on 5 March 1610, printed in Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). pp. 265–266, 276–278. OCLC 654683776.

- Craft, Kimberley L. (2009). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 80.

- Did Dracula really exist? from The Straight Dope

- Thorne, Tony (29 June 2008). "Countess Elizabeth Báthory: icon of evil". The Telegraph. London, England: Telegraph Media Group.

- Dr. Szádeczky-Kardoss Irma - Báthory Erzsébet igazsága - 10 years of research using contemporary correspondence)

- Thorne, Tony (1997). Countess Dracula. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 18–19.

- A letter from 12 December 1610 by Elizabeth's son-in-law Zrínyi to Thurzó refers to an agreement made earlier. See Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). p. 291. OCLC 654683776.

- Rachael Leigh Bledsaw: No Blood in the Water: The Legal and Gender Conspiracies Against Countess Elizabeth Bathory in Historical Context

- Szádeczky-Kardoss Irma - Báthory Erzsébet igazsága / The truth of Elizabeth Báthory (10 years of research using contemporary correspondence)

- Lengyel Tünde, Várkonyi Gábor: Báthory Erzsébet - egy asszony élete / Life of a woman

- Infamous Lady the true story of Countess Erzsebet Bathory Kimberly L. Craft 2009 p.298

- Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). p. 246. OCLC 654683776.

- "Find A Grave". Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Nagy, László. A rossz hirü Báthoryak. Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó 1984

- "The Bloody Countess?". Élet és Tudomány (Life and Science). Retrieved 2 September 2005.

- Szakály, Ferenc (1994). "The Early Ottoman Period, Including Royal Hungary, 1526–1606". In Sugar, Peter F. (ed.). A History of Hungary. pp. 83–99. ISBN 978-0-253-20867-5.

- Thorne, Tony. 'Countess Dracula: The Life and Times of Elisabeth Bathory, the Blood Countess'

- in Ungaria suis *** regibus compendia data, Typis Academicis Soc. Jesu per Fridericum Gall. Anno MCCCXXIX. Mense Sepembri Die 8. p 188–193, quoted by Farin

- Hesperus, Prague, June 1817, Vol. 1, No. 31, pp. 241–248 and July 1817, Vol. 2, No. 34, pp. 270–272

- Paget, John (1850). Hungary and Transylvania; with remarks on their condition, Social, Political and Economical. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard. pp. 50–51.

- Alois Freyherr von Mednyansky: Elisabeth Báthory, in Hesperus, Prague, October 1812, vol. 2, No. 59, pp. 470–472, quoted by Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). pp. 61–65. OCLC 654683776.

- Horn, Ildikó (2002). Báthory András [Andrew Báthory] (in Hungarian). Új Mandátum. pp. 245–246. ISBN 978-963-9336-51-3.

- Markó, László (2000). A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig: Életrajzi Lexikon [Great Officers of State in Hungary from King Saint Stephen to Our Days: A Biographical Encyclopedia] (in Hungarian). Magyar Könyvklub. p. 256. ISBN 978-963-547-085-3.

Further reading

- McNally, Raymond T. (1983). Dracula Was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-045671-6. Raymond T. McNally (1931–2002) was a professor of Russian and East European History at Boston College

- Thorne, Tony (1997). Countess Dracula. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-2900-2.

- Penrose, Valentine (2006). The Bloody Countess: Atrocities of Erzsébet Báthory. translator: Trocchi, Alexander. Solar Books. ISBN 978-0-9714578-2-9. Translation from the French Erzsébet Báthory la Comtesse sanglante

- Craft, Kimberly (2009). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory. ISBN 978-1-4495-1344-3.

- Ramsland, Katherine. "Lady of Blood: Countess Bathory". Crime Library. Turner Entertainment Networks Inc. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014.

- Zsuffa, Joseph (2015). Countess of the Moon. Griffin Press. ISBN 978-0-9828813-8-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elizabeth Báthory. |

- The Blood Countess? - Epitome of Dr. Szádeczky-Kardoss Irma's research

- Elizabeth Báthory at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Elizabeth Bathory - the Blood Countess BBC piece on Erzsébet Báthory, Created 2 August 2001; Updated 28 January 2002

- "Elizabeth Báthory Drop of Blood Festival: 16 August 2014" (in Slovak). Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Festival in Čachtice, Slovakia

- Marek, Miroslav. "A genealogy of the Nádasdy family, including her descendants". Genealogy.EU.

- Marek, Miroslav. "A genealogy of the Báthory family". Genealogy.EU.

- A complete genealogy of all descendants Elizabeth Báthory (17th-20th century)

- Novotny, Pavel (Director) (2014). Die Gräfin Elisabeth Bathory und das Geheimnis hinter dem Geheimnis [400 Years of Bloody Countess - The Secret Behind the Secret] (Motion picture). Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2014. (Documentary film)