Dream

A dream is a succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that usually occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep.[1] The content and purpose of dreams are not fully understood, although they have been a topic of scientific, philosophical and religious interest throughout recorded history. Dream interpretation is the attempt at drawing meaning from dreams and searching for an underlying message. The scientific study of dreams is called oneirology.[2]

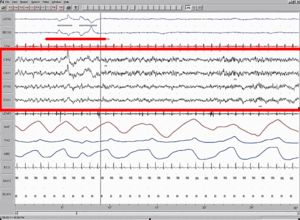

Dreams mainly occur in the rapid-eye movement (REM) stage of sleep—when brain activity is high and resembles that of being awake. REM sleep is revealed by continuous movements of the eyes during sleep. At times, dreams may occur during other stages of sleep. However, these dreams tend to be much less vivid or memorable.[3] The length of a dream can vary; they may last for a few seconds, or approximately 20–30 minutes.[3] People are more likely to remember the dream if they are awakened during the REM phase. The average person has three to five dreams per night, and some may have up to seven;[4] however, most dreams are immediately or quickly forgotten.[5] Dreams tend to last longer as the night progresses. During a full eight-hour night sleep, most dreams occur in the typical two hours of REM.[6] Dreams related to waking-life experiences are associated with REM theta activity, which suggests that emotional memory processing takes place in REM sleep.[7]

Opinions about the meaning of dreams have varied and shifted through time and culture. Many endorse the Freudian theory of dreams – that dreams reveal insight into hidden desires and emotions. Other prominent theories include those suggesting that dreams assist in memory formation, problem solving, or simply are a product of random brain activation.[8]

Sigmund Freud, who developed the psychological discipline of psychoanalysis, wrote extensively about dream theories and their interpretations in the early 1900s.[9] He explained dreams as manifestations of one's deepest desires and anxieties, often relating to repressed childhood memories or obsessions. Furthermore, he believed that virtually every dream topic, regardless of its content, represented the release of sexual tension.[10] In The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), Freud developed a psychological technique to interpret dreams and devised a series of guidelines to understand the symbols and motifs that appear in our dreams. In modern times, dreams have been seen as a connection to the unconscious mind. They range from normal and ordinary to overly surreal and bizarre. Dreams can have varying natures, such as being frightening, exciting, magical, melancholic, adventurous, or sexual. The events in dreams are generally outside the control of the dreamer, with the exception of lucid dreaming, where the dreamer is self-aware.[11] Dreams can at times make a creative thought occur to the person or give a sense of inspiration.[12]

Cultural meaning

Ancient history

The Dreaming is a common term within the animist creation narrative of indigenous Australians for a personal, or group, creation and for what may be understood as the "timeless time" of formative creation and perpetual creating.[13]

The ancient Sumerians in Mesopotamia have left evidence of dream interpretation dating back to at least 3100 BC.[14][15] Throughout Mesopotamian history, dreams were always held to be extremely important for divination[15][16] and Mesopotamian kings paid close attention to them.[15][14] Gudea, the king of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash (reigned c. 2144–2124 BC), rebuilt the temple of Ningirsu as the result of a dream in which he was told to do so.[15] The standard Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh contains numerous accounts of the prophetic power of dreams.[15] First, Gilgamesh himself has two dreams foretelling the arrival of Enkidu.[15] Later, Enkidu dreams about the heroes' encounter with the giant Humbaba.[15] Dreams were also sometimes seen as a means of seeing into other worlds[15] and it was thought that the soul, or some part of it, moved out of the body of the sleeping person and actually visited the places and persons the dreamer saw in his or her sleep.[17] In Tablet VII of the epic, Enkidu recounts to Gilgamesh a dream in which he saw the gods Anu, Enlil, and Shamash condemn him to death.[15] He also has a dream in which he visits the Underworld.[15]

The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883–859 BC) built a temple to Mamu, possibly the god of dreams, at Imgur-Enlil, near Kalhu.[15] The later Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–c. 627 BC) had a dream during a desperate military situation in which his divine patron, the goddess Ishtar, appeared to him and promised that she would lead him to victory.[15] The Babylonians and Assyrians divided dreams into "good," which were sent by the gods, and "bad," sent by demons.[16] A surviving collection of dream omens entitled Iškar Zaqīqu records various dream scenarios as well as prognostications of what will happen to the person who experiences each dream, apparently based on previous cases.[15][18] Some list different possible outcomes, based on occasions in which people experienced similar dreams with different results.[15] Dream scenarios mentioned include a variety of daily work events, journeys to different locations, family matters, sex acts, and encounters with human individuals, animals, and deities.[15]

In ancient Egypt, as far back as 2000 BC, the Egyptians wrote down their dreams on papyrus. People with vivid and significant dreams were thought to be blessed and were considered special.[19] Ancient Egyptians believed that dreams were like oracles, bringing messages from the gods. They thought that the best way to receive divine revelation was through dreaming and thus they would induce (or "incubate") dreams. Egyptians would go to sanctuaries and sleep on special "dream beds" in hope of receiving advice, comfort, or healing from the gods.[20]

Classical history

In Chinese history, people wrote of two vital aspects of the soul of which one is freed from the body during slumber to journey in a dream realm, while the other remained in the body,[21] although this belief and dream interpretation had been questioned since early times, such as by the philosopher Wang Chong (27–97 AD).[21] The Indian text Upanishads, written between 900 and 500 BC, emphasizes two meanings of dreams. The first says that dreams are merely expressions of inner desires. The second is the belief of the soul leaving the body and being guided until awakened.

The Greeks shared their beliefs with the Egyptians on how to interpret good and bad dreams, and the idea of incubating dreams. Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams, also sent warnings and prophecies to those who slept at shrines and temples. The earliest Greek beliefs about dreams were that their gods physically visited the dreamers, where they entered through a keyhole, exiting the same way after the divine message was given.

Antiphon wrote the first known Greek book on dreams in the 5th century BC. In that century, other cultures influenced Greeks to develop the belief that souls left the sleeping body.[22] Hippocrates (469–399 BC) had a simple dream theory: during the day, the soul receives images; during the night, it produces images. Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC) believed dreams caused physiological activity. He thought dreams could analyze illness and predict diseases. Marcus Tullius Cicero, for his part, believed that all dreams are produced by thoughts and conversations a dreamer had during the preceding days.[23] Cicero's Somnium Scipionis described a lengthy dream vision, which in turn was commented on by Macrobius in his Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis.

Herodotus in his The Histories, writes "The visions that occur to us in dreams are, more often than not, the things we have been concerned about during the day."[24]

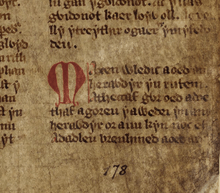

In Welsh history, The Dream of Rhonabwy (Welsh: Breuddwyd Rhonabwy) is a Middle Welsh prose tale. Set during the reign of Madog ap Maredudd, prince of Powys (died 1160), it is dated to the late 12th or 13th century. It survives in only one manuscript, the Red Book of Hergest, and has been associated with the Mabinogion since its publication by Lady Charlotte Guest in the 19th century. The bulk of the narrative describes a dream vision experienced by its central character, Rhonabwy, a retainer of Madog, in which he visits the time of King Arthur.[25]

Also in Welsh history, the tale 'The Dream of Macsen Wledig' is a romanticised story about the Roman emperor Magnus Maximus, called Macsen Wledig in Welsh. Born in Hispania, he became a legionary commander in Britain, assembled a Celtic army and assumed the title of Emperor of the Western Roman Empire in 383. He was defeated in battle in 385 and beheaded at the direction of the Eastern Roman emperor.[26]

Religious views

In Abrahamic religions

In Judaism, dreams are considered part of the experience of the world that can be interpreted and from which lessons can be garnered. It is discussed in the Talmud, Tractate Berachot 55–60.

The ancient Hebrews connected their dreams heavily with their religion, though the Hebrews were monotheistic and believed that dreams were the voice of one God alone. Hebrews also differentiated between good dreams (from God) and bad dreams (from evil spirits). The Hebrews, like many other ancient cultures, incubated dreams in order to receive a divine revelation. For example, the Hebrew prophet Samuel would "lie down and sleep in the temple at Shiloh before the Ark and receive the word of the Lord." Most of the dreams in the Bible are in the Book of Genesis.[27]

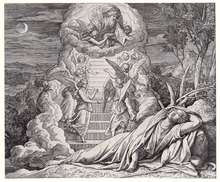

Christians mostly shared the beliefs of the Hebrews and thought that dreams were of a supernatural character because the Old Testament includes frequent stories of dreams with divine inspiration. The most famous of these dream stories was Jacob's dream of a ladder that stretches from Earth to Heaven. Many Christians preach that God can speak to people through their dreams. The famous glossary, the Somniale Danielis, written in the name of Daniel, attempted to teach Christian populations to interpret their dreams.

Iain R. Edgar has researched the role of dreams in Islam.[28] He has argued that dreams play an important role in the history of Islam and the lives of Muslims, since dream interpretation is the only way that Muslims can receive revelations from God since the death of the last prophet, Muhammad.[29]

In Hinduism

In the Mandukya Upanishad, part of the Veda scriptures of Indian Hinduism, a dream is one of three states that the soul experiences during its lifetime, the other two states being the waking state and the sleep state.[30]

In Buddhism

In Buddhism, ideas about dreams are similar to the classical and folk traditions in South Asia. The same dream is sometimes experienced by multiple people, as in the case of the Buddha-to-be, before he is leaving his home. It is described in the Mahāvastu that several of the Buddha's relatives had premonitory dreams preceding this. Some dreams are also seen to transcend time: the Buddha-to-be has certain dreams that are the same as those of previous Buddhas, the Lalitavistara states. In Buddhist literature, dreams often function as a "signpost" motif to mark certain stages in the life of the main character.[31]

Buddhist views about dreams are expressed in the Pāli Commentaries and the Milinda Pañhā.[31]

Dreams and philosophical realism

Some philosophers have concluded that what we think of as the "real world" could be or is an illusion (an idea known as the skeptical hypothesis about ontology).

The first recorded mention of the idea was by Zhuangzi, and it is also discussed in Hinduism, which makes extensive use of the argument in its writings.[32] It was formally introduced to Western philosophy by Descartes in the 17th century in his Meditations on First Philosophy. Stimulus, usually an auditory one, becomes a part of a dream, eventually then awakening the dreamer.

Postclassical and medieval history

Some Indigenous American tribes and Mexican civilizations believe that dreams are a way of visiting and having contact with their ancestors.[33] Some Native American tribes used vision quests as a rite of passage, fasting and praying until an anticipated guiding dream was received, to be shared with the rest of the tribe upon their return.[34][35]

The Middle Ages brought a harsh interpretation of dreams. They were seen as evil, and the images as temptations from the devil. Many believed that during sleep, the devil could fill the human mind with corrupting and harmful thoughts. Martin Luther, the Protestant Reformer, believed dreams were the work of the Devil. However, Catholics such as St. Augustine and St. Jerome claimed that the direction of their lives was heavily influenced by their dreams.

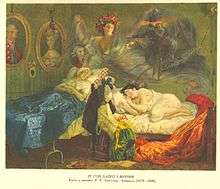

In art

The depiction of dreams in Renaissance and Baroque art is often related to Biblical narrative. Examples are Joachim's Dream (1304–1306) from the Scrovegni Chapel fresco cycle by Giotto, and Jacob's Dream (1639) by Jusepe de Ribera. Dreams and dark imaginings are the theme of several notable works of the Romantic era, such as Goya's etching The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (c. 1799) and Henry Fuseli's painting The Nightmare (1781). Salvador Dalí's Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (1944) also investigates this theme through absurd juxtapositions of a nude lady, tigers leaping out of a pomegranate, and a spiderlike elephant walking in the background. Henri Rousseau's last painting was The Dream. Le Rêve ("The Dream") is a 1932 painting by Pablo Picasso.

In literature

Dream frames were frequently used in medieval allegory to justify the narrative; The Book of the Duchess[36] and The Vision Concerning Piers Plowman[37] are two such dream visions. Even before them, in antiquity, the same device had been used by Cicero and Lucian of Samosata.

They have also featured in fantasy and speculative fiction since the 19th century. One of the best-known dream worlds is Wonderland from Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, as well as Looking-Glass Land from its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass. Unlike many dream worlds, Carroll's logic is like that of actual dreams, with transitions and flexible causality.

Other fictional dream worlds include the Dreamlands of H.P. Lovecraft's Dream Cycle[38] and The Neverending Story's[39] world of Fantasia, which includes places like the Desert of Lost Dreams, the Sea of Possibilities and the Swamps of Sadness. Dreamworlds, shared hallucinations and other alternate realities feature in a number of works by Philip K. Dick, such as The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch and Ubik. Similar themes were explored by Jorge Luis Borges, for instance in The Circular Ruins.

In popular culture

.jpg)

Modern popular culture often conceives of dreams, like Freud, as expressions of the dreamer's deepest fears and desires.[40] The film version of The Wizard of Oz (1939) depicts a full-color dream that causes Dorothy to perceive her black-and-white reality and those with whom she shares it in a new way. In films such as Spellbound (1945), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), and Inception (2010), the protagonists must extract vital clues from surreal dreams.[41]

Most dreams in popular culture are, however, not symbolic, but straightforward and realistic depictions of their dreamer's fears and desires.[41] Dream scenes may be indistinguishable from those set in the dreamer's real world, a narrative device that undermines the dreamer's and the audience's sense of security[41] and allows horror film protagonists, such as those of Carrie (1976), Friday the 13th (1980) or An American Werewolf in London (1981) to be suddenly attacked by dark forces while resting in seemingly safe places.[41]

In speculative fiction, the line between dreams and reality may be blurred even more in the service of the story.[41] Dreams may be psychically invaded or manipulated (Dreamscape, 1984; the Nightmare on Elm Street films, 1984–2010; Inception, 2010) or even come literally true (as in The Lathe of Heaven, 1971). In Ursula K. Le Guin's book, The Lathe of Heaven (1971), the protagonist finds that his "effective" dreams can retroactively change reality. Peter Weir's 1977 Australian film The Last Wave makes a simple and straightforward postulate about the premonitory nature of dreams (from one of his Aboriginal characters) that "... dreams are the shadow of something real". In Kyell Gold's novel Green Fairy from the Dangerous Spirits series, the protagonist, Sol, experiences the memories of a dancer who died 100 years before through Absinthe induced dreams and after each dream something from it materializes into his reality. Such stories play to audiences' experiences with their own dreams, which feel as real to them.[41]

Neurobiology

REM versus non-REM sleep dreaming

Distinct types of dreams have been identified for REM and non-REM sleep stages. The vivid bizarre dreams that are commonly remembered upon waking up are primarily associated with REM sleep. Deep (stage 3 and 4) slow-wave sleep (NREM sleep) is commonly associated with more static, thoughtful dreams.[42] These dreams are primarily driven by the hippocampus in the process of long-term memory consolidation and predominantly include memories of events “as they happened” without the random novel combination of objects seen in REM sleep dreams. The rest of the article focuses on REM sleep dreaming, thereafter simply referred as dreaming.

REM sleep

Since waking up usually happens during rapid eye movement sleep (REM), the vivid bizarre REM sleep dreams are the most common type of dreams that is remembered. (During REM sleep an electroencephalogram (EEG) shows brain activity that, among sleep states, is most like wakefulness.) During a typical lifespan, a person spends a total of about six years dreaming[43] (which is about two hours each night).[44] Most dreams only last 5 to 20 minutes.[43] It is unknown where in the brain dreams originate, if there is a single origin for dreams or if multiple portions of the brain are involved, or what the purpose of dreaming is for the body or mind.

During REM sleep, the release of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine, serotonin and histamine is completely suppressed.[3][45][46]

During most dreams, the person dreaming is not aware that they are dreaming, no matter how absurd or eccentric the dream is. The reason for this may be that the prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain responsible for logic and planning, exhibits decreased activity during dreams. This allows the dreamer to more actively interact with the dream without thinking about what might happen, since things that would normally stand out in reality blend in with the dream scenery.[47]

When REM sleep episodes were timed for their duration and subjects were awakened to make reports before major editing or forgetting of their dreams could take place, subjects accurately reported the length of time they had been dreaming in an REM sleep state. Some researchers have speculated that "time dilation" effects only seem to be taking place upon reflection and do not truly occur within dreams.[48] This close correlation of REM sleep and dream experience was the basis of the first series of reports describing the nature of dreaming: that it is a regular nightly rather than occasional phenomenon, and is correlated with high-frequency activity within each sleep period occurring at predictable intervals of approximately every 60–90 minutes in all humans throughout the lifespan.

REM sleep episodes and the dreams that accompany them lengthen progressively through the night, with the first episode being the shortest, of approximately 10–12 minutes duration, and the second and third episodes increasing to 15–20 minutes. Dreams at the end of the night may last as long as 15 minutes, although these may be experienced as several distinct episodes due to momentary arousals interrupting sleep as the night ends. Dream reports can be reported from normal subjects 50% of the time when they are awakened prior to the end of the first REM period. This rate of retrieval is increased to about 99% when awakenings are made from the last REM period of the night. The increase in the ability to recall dreams appears related to intensification across the night in the vividness of dream imagery, colors, and emotions.[49]

Brain activity

One of the central questions of sleep research is what part of the brain is driving dreams' video-auditory experience. During waking, most of the mind's internal imagery is controlled from the front of the brain by the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC). Reasoning, planning, and strategizing are the results of the constructive imagination conducted by the LPFC, which acts like a puppeteer assembling objects stored in memory into novel combinations. During REM sleep, however the LPFC is inactive.[50][51] Furthermore, in people whose LPFC is damaged, dreams do not change at all, confirming that LPFC does not control dreaming.[52]

During deep slow-wave sleep, imagery is primarily driven by the hippocampus in the process of long-term memory consolidation and predominantly includes memories of events “as they happened” without the random novel combination of objects seen in REM sleep dreams. During REM sleep, however, the communication between the neocortex and the hippocampus is disrupted by a high ACh level.[53]

Without being driven by the LPFC (as in waking) and hippocampus (as in slow-wave sleep), it is unclear how exactly images appear in one's perception during REM sleep. A common explanation is that neuronal ensembles in the posterior cortical hot zone, primed by previous activity or current sensory or subcortical stimulation, activate spontaneously, triggered by the ponto-geniculo-occipital (PGO) waves that characterize REM sleep.[54] In the words of Hobson & McCarley, the neocortex is making “the best of a bad job in producing even partially coherent dream imagery from the relatively noisy signals sent up from the brain stem.”[55]

It is also commonly accepted that the intensity of dreams during REM sleep can be dialed up or down by the dopaminergic cells of the ventral tegmental area. For example, drugs that block dopaminergic activity (e.g., haloperidol) inhibit unusually frequent and vivid dreaming, while the increase of dopamine (e.g., through l-dopa) stimulates excessive vivid dreaming and nightmares.[55]

In other animal species

REM sleep and the ability to dream seem to be embedded in the biology of many animals in addition to humans. Scientific research suggests that all mammals experience REM.[58] The range of REM can be seen across species: dolphins experience minimal REM, while humans are in the middle of the scale and the armadillo and the opossum (a marsupial) are among the most prolific dreamers, judging from their REM patterns.[59]

Studies have observed signs of dreaming in all mammals studied, including monkeys, dogs, cats, rats, elephants, and shrews. There have also been signs of dreaming in birds and reptiles.[60] Sleeping and dreaming are intertwined. Scientific research results regarding the function of dreaming in animals remain disputable; however, the function of sleeping in living organisms is increasingly clear. For example, sleep deprivation experiments conducted on rats and other animals have resulted in the deterioration of physiological functioning and actual tissue damage.[61]

Some scientists argue that humans dream for the same reason other amniotes do. From a Darwinian perspective dreams would have to fulfill some kind of biological requirement, provide some benefit for natural selection to take place, or at least have no negative impact on fitness. In 2000 Antti Revonsuo, a professor at the University of Turku in Finland, claimed that centuries ago dreams would prepare humans for recognizing and avoiding danger by presenting a simulation of threatening events. The theory has therefore been called the threat-simulation theory.[62] According to Tsoukalas (2012) dreaming is related to the reactive patterns elicited by encounters with predators, a fact that is still evident in the control mechanisms of REM sleep (see below).[63][64]

Function

Many hypotheses have been proposed as to what function dreams perform, some of which have been contradicted by later empirical studies. It has also been proposed that dreams serve no particular purpose, and that they are simply a byproduct of biochemical processes that only occur in the brain during sleep.

Dynamic psychiatry

Freud's view

In the late 19th century, psychotherapist Sigmund Freud developed a theory (since discredited) that the content of dreams is driven by unconscious wish fulfillment. Freud called dreams the "royal road to the unconscious."[65] He theorized that the content of dreams reflects the dreamer's unconscious mind and specifically that dream content is shaped by unconscious wish fulfillment. He argued that important unconscious desires often relate to early childhood memories and experiences. Freud's theory describes dreams as having both manifest and latent content. Latent content relates to deep unconscious wishes or fantasies while manifest content is superficial and meaningless.[66] Manifest content often masks or obscures latent content.[67]

In his early work, Freud argued that the vast majority of latent dream content is sexual in nature, but he later moved away from this categorical position. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle he considered how trauma or aggression could influence dream content. He also discussed supernatural origins in Dreams and Occultism, a lecture published in New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis.[68]

Late in life Freud acknowledged that "It is impossible to classify as wish fulfillments" the repetitive nightmares associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Modern experimental studies weigh against many of Freud's theories regarding dreams. Freud's "dream-work" interpretation strategies have not been found to have empirical validity. His theory that dreams were the "guardians" of sleep, repressing and disguising bodily urges to ensure sleep continues, seems unlikely given studies of individuals who can sleep without dreaming. His assertions that repressed memory in infants re-surface decades later in adult dreams conflicts with modern research on memory. Freud's theory has difficulty explaining why young children have static and bland dreams, or why the emotions in most dreams are negative. On the plus side, modern researchers agree with Freud that dreams do have coherence, and that dream content connects to other psychological variables and often connect to recent waking thoughts (though not as often as Freud supposed).[69] Despite the lack of scientific evidence, dream interpretation services based on Freudian or other systems remain popular.[70]

Jung's view

Carl Jung rejected many of Freud's theories. Jung expanded on Freud's idea that dream content relates to the dreamer's unconscious desires. He described dreams as messages to the dreamer and argued that dreamers should pay attention for their own good. He came to believe that dreams present the dreamer with revelations that can uncover and help to resolve emotional or religious problems and fears.[71]

Jung wrote that recurring dreams show up repeatedly to demand attention, suggesting that the dreamer is neglecting an issue related to the dream. He called this "compensation." The dream balances the conscious belief and attitudes with an alternative. Jung did not believe that the conscious attitude was wrong and that the dream provided the true belief. He argued that good work with dreams takes both into account and comes up with a balanced viewpoint. He believed that many of the symbols or images from these dreams return with each dream. Jung believed that memories formed throughout the day also play a role in dreaming. These memories leave impressions for the unconscious to deal with when the ego is at rest. The unconscious mind re-enacts these glimpses of the past in the form of a dream. Jung called this a day residue.[72] Jung also argued that dreaming is not a purely individual concern, that all dreams are part of "one great web of psychological factors."

Fritz Perls' view

Fritz Perls presented his theory of dreams as part of the holistic nature of Gestalt therapy. Dreams are seen as projections of parts of the self that have been ignored, rejected, or suppressed.[73] Jung argued that one could consider every person in the dream to represent an aspect of the dreamer, which he called the subjective approach to dreams. Perls expanded this point of view to say that even inanimate objects in the dream may represent aspects of the dreamer. The dreamer may, therefore, be asked to imagine being an object in the dream and to describe it, in order to bring into awareness the characteristics of the object that correspond with the dreamer's personality.

Neurological theories

Activation synthesis theory

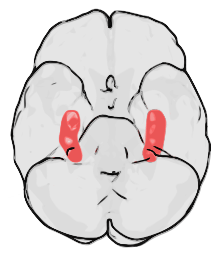

In 1976 J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley proposed a new theory that changed dream research, challenging the previously held Freudian view of dreams as unconscious wishes to be interpreted. They assume that the same structures that induce REM sleep also generate sensory information. Hobson's 1976 research suggested that the signals interpreted as dreams originate in the brainstem during REM sleep. According to Hobson and other researchers, circuits in the brainstem are activated during REM sleep. Once these circuits are activated, areas of the limbic system involved in emotions, sensations, and memories, including the amygdala and hippocampus, become active. The brain synthesizes and interprets these activities; for example, changes in the physical environment such as temperature and humidity, or physical stimuli such as ejaculation, and attempts to create meaning from these signals, result in dreaming.

However, research by Mark Solms suggests that dreams are generated in the forebrain, and that REM sleep and dreaming are not directly related.[74] While working in the neurosurgery department at hospitals in Johannesburg and London, Solms had access to patients with various brain injuries. He began to question patients about their dreams and confirmed that patients with damage to the parietal lobe stopped dreaming; this finding was in line with Hobson's 1977 theory. However, Solms did not encounter cases of loss of dreaming with patients having brainstem damage. This observation forced him to question Hobson's prevailing theory, which marked the brainstem as the source of the signals interpreted as dreams.

Continual-activation theory

Combining Hobson's activation synthesis hypothesis with Solms' findings, the continual-activation theory of dreaming presented by Jie Zhang proposes that dreaming is a result of brain activation and synthesis; at the same time, dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms. Zhang hypothesizes that the function of sleep is to process, encode, and transfer the data from the temporary memory store to the long-term memory store. During NREM sleep the conscious-related memory (declarative memory) is processed, and during REM sleep the unconscious-related memory (procedural memory) is processed.[75]

Zhang assumes that during REM sleep the unconscious part of a brain is busy processing the procedural memory; meanwhile, the level of activation in the conscious part of the brain descends to a very low level as the inputs from the sensory systems are basically disconnected. This triggers the "continual-activation" mechanism to generate a data stream from the memory stores to flow through the conscious part of the brain. Zhang suggests that this pulsatile brain activation is the inducer of each dream. He proposes that, with the involvement of the brain associative thinking system, dreaming is, thereafter, self-maintained with the dreamer's own thinking until the next pulse of memory insertion. This explains why dreams have both characteristics of continuity (within a dream) and sudden changes (between two dreams).[75][76] A detailed explanation of how a dream is synthesized is given in a later paper.[77]

Defensive immobilization: the precursor

According to Tsoukalas (2012) REM sleep is an evolutionary transformation of a well-known defensive mechanism, the tonic immobility reflex. This reflex, also known as animal hypnosis or death feigning, functions as the last line of defense against an attacking predator and consists of the total immobilization of the animal: the animal appears dead (cf. "playing possum"). Tsoukalas claims that the neurophysiology and phenomenology of this reaction shows striking similarities to REM sleep, a fact that suggests a deep evolutionary kinship. For example, both reactions exhibit brainstem control, paralysis, hippocampal theta and thermoregulatory changes. Tsoukalas claims that this theory integrates many earlier findings into a unified framework.[63][64]

As excitations of long-term memory

Eugen Tarnow suggests that dreams are ever-present excitations of long-term memory, even during waking life. The strangeness of dreams is due to the format of long-term memory, reminiscent of Penfield & Rasmussen's findings that electrical excitations of the cortex give rise to experiences similar to dreams. During waking life an executive function interprets long-term memory consistent with reality checking. Tarnow's theory is a reworking of Freud's theory of dreams in which Freud's unconscious is replaced with the long-term memory system and Freud's "Dream Work" describes the structure of long-term memory.[78]

Role in strengthening semantic memories

A 2001 study showed evidence that illogical locations, characters, and dream flow may help the brain strengthen the linking and consolidation of semantic memories.[79] These conditions may occur because, during REM sleep, the flow of information between the hippocampus and neocortex is reduced.[80]

Increasing levels of the stress hormone cortisol late in sleep (often during REM sleep) causes this decreased communication. One stage of memory consolidation is the linking of distant but related memories. Payne and Nadal hypothesize these memories are then consolidated into a smooth narrative, similar to a process that happens when memories are created under stress.[81] Robert (1886),[82] a physician from Hamburg, was the first who suggested that dreams are a need and that they have the function to erase (a) sensory impressions that were not fully worked up, and (b) ideas that were not fully developed during the day. By the dream work, incomplete material is either removed (suppressed) or deepened and included into memory. Robert's ideas were cited repeatedly by Freud in his Die Traumdeutung. Hughlings Jackson (1911) viewed that sleep serves to sweep away unnecessary memories and connections from the day.

This was revised in 1983 by Crick and Mitchison's "reverse learning" theory, which states that dreams are like the cleaning-up operations of computers when they are offline, removing (suppressing) parasitic nodes and other "junk" from the mind during sleep.[83][84] However, the opposite view that dreaming has an information handling, memory-consolidating function (Hennevin and Leconte, 1971) is also common.

Psychological theories

Role in testing and selecting mental schemas

Coutts[85] describes dreams as playing a central role in a two-phase sleep process that improves the mind's ability to meet human needs during wakefulness. During the accommodation phase, mental schemas self-modify by incorporating dream themes. During the emotional selection phase, dreams test prior schema accommodations. Those that appear adaptive are retained, while those that appear maladaptive are culled. The cycle maps to the sleep cycle, repeating several times during a typical night's sleep. Alfred Adler suggested that dreams are often emotional preparations for solving problems, intoxicating an individual away from common sense toward private logic. The residual dream feelings may either reinforce or inhibit contemplated action.

Evolutionary psychology theories

Numerous theories state that dreaming is a random by-product of REM sleep physiology and that it does not serve any natural purpose.[86] Flanagan claims that "dreams are evolutionary epiphenomena" and they have no adaptive function. "Dreaming came along as a free ride on a system designed to think and to sleep."[87]

J.A. Hobson, for different reasons, also considers dreams epiphenomena. He believes that the substance of dreams have no significant influence on waking actions, and most people go about their daily lives perfectly well without remembering their dreams.[88] Hobson proposed the activation-synthesis theory, which states that "there is a randomness of dream imagery and the randomness synthesizes dream-generated images to fit the patterns of internally generated stimulations".[89] This theory is based on the physiology of REM sleep, and Hobson believes dreams are the outcome of the forebrain reacting to random activity beginning at the brainstem. The activation-synthesis theory hypothesizes that the peculiar nature of dreams is attributed to certain parts of the brain trying to piece together a story out of what is essentially bizarre information.[90] In 2005, Hobson published a book, Thirteen Dreams that Freud Never Had,[91] in which he analyzed his own dreams after having a stroke in 2001.

Some evolutionary psychologists believe dreams serve some adaptive function for survival. Deirdre Barrett describes dreaming as simply "thinking in different biochemical state" and believes people continue to work on all the same problems—personal and objective—in that state.[92] Her research finds that anything—math, musical composition, business dilemmas—may get solved during dreaming.[93][94]

Finnish psychologist Antti Revonsuo posits that dreams have evolved for "threat simulation" exclusively. According to the Threat Simulation Theory he proposes, during much of human evolution physical and interpersonal threats were serious, giving reproductive advantage to those who survived them. Therefore, dreaming evolved to replicate these threats and continually practice dealing with them. In support of this theory, Revonsuo shows that contemporary dreams comprise much more threatening events than people meet in daily non-dream life, and the dreamer usually engages appropriately with them.[95] It is suggested by this theory that dreams serve the purpose of allowing for the rehearsal of threatening scenarios in order to better prepare an individual for real-life threats.

According to Tsoukalas (2012) the biology of dreaming is related to the reactive patterns elicited by predatorial encounters (especially the tonic immobility reflex), a fact that lends support to evolutionary theories claiming that dreams specialize in threat avoidance or emotional processing.[63]

Other hypotheses

There are many other hypotheses about the function of dreams, including:[96]

- Dreams allow the repressed parts of the mind to be satisfied through fantasy while keeping the conscious mind from thoughts that would suddenly cause one to awaken from shock.[97]

- Ferenczi[98] proposed that the dream, when told, may communicate something that is not being said outright.

- Dreams regulate mood.[99]

- Hartmann[100] says dreams may function like psychotherapy, by "making connections in a safe place" and allowing the dreamer to integrate thoughts that may be dissociated during waking life.

- LaBerge and DeGracia[101] have suggested that dreams may function, in part, to recombine unconscious elements within consciousness on a temporary basis by a process they term "mental recombination", in analogy with genetic recombination of DNA. From a bio-computational viewpoint, mental recombination may contribute to maintaining an optimal information processing flexibility in brain information networks.

Content

From the 1940s to 1985, Calvin S. Hall collected more than 50,000 dream reports at Western Reserve University. In 1966 Hall and Van De Castle published The Content Analysis of Dreams, in which they outlined a coding system to study 1,000 dream reports from college students.[102] Results indicated that participants from varying parts of the world demonstrated similarity in their dream content. Hall's complete dream reports were made publicly available in the mid-1990s by Hall's protégé William Domhoff.

Visuals

The visual nature of dreams is generally highly phantasmagoric; that is, different locations and objects continuously blend into each other. The visuals (including locations, characters/people, objects/artifacts) are generally reflective of a person's memories and experiences, but conversation can take on highly exaggerated and bizarre forms. Some dreams may even tell elaborate stories wherein the dreamer enters entirely new, complex worlds and awakes with ideas, thoughts and feelings never experienced prior to the dream.

People who are blind from birth do not have visual dreams. Their dream contents are related to other senses like hearing, touch, smell and taste, whichever are present since birth.[103]

Emotions

In the Hall study, the most common emotion experienced in dreams was anxiety. Other emotions included abandonment, anger, fear, joy, and happiness. Negative emotions were much more common than positive ones.[102]

Sexual themes

The Hall data analysis shows that sexual dreams occur no more than 10% of the time and are more prevalent in young to mid-teens.[102] Another study showed that 8% of both men and women's dreams have sexual content.[104] In some cases, sexual dreams may result in orgasms or nocturnal emissions. These are colloquially known as wet dreams.[105]

Color vs. black-and-white

A small minority of people say that they dream only in black and white.[106] A 2008 study by a researcher at the University of Dundee found that people who were only exposed to black-and-white television and film in childhood reported dreaming in black and white about 25% of the time.[107]

Relationship with medical conditions

There is evidence that certain medical conditions (normally only neurological conditions) can impact dreams. For instance, some people with synesthesia have never reported entirely black-and-white dreaming, and often have a difficult time imagining the idea of dreaming in only black and white.[108]

Interpretations

Common interpretations

Dream interpretation can be a result of subjective ideas and experiences. One study[8] found that most people believe that "their dreams reveal meaningful hidden truths". In one study[109] conducted in the United States, South Korea and India, they found that 74% of Indians, 65% of South Koreans and 56% of Americans believed their dream content provided them with meaningful insight into their unconscious beliefs and desires. This Freudian view of dreaming was believed by the largely non-scientific public significantly more than theories of dreaming that attribute dream content to memory consolidation, problem-solving, or random brain activity.

Importance

In the paper, Morewedge and Norton (2009) also found that people attribute more importance to dream content than to similar thought content that occurs while they are awake. In one study, Americans were more likely to report that they would miss their flight if they dreamt of their plane crashing than if they thought of their plane crashing the night before flying (while awake), and that they would be as likely to miss their flight if they dreamt of their plane crashing the night before their flight as if there was an actual plane crash on the route they intended to take.[8] Not all dream content was considered equally important. Participants in their studies were more likely to perceive dreams to be meaningful when the content of dreams was in accordance with their beliefs and desires while awake. People were more likely to view a positive dream about a friend to be meaningful than a positive dream about someone they disliked, for example, and were more likely to view a negative dream about a person they disliked as meaningful than a negative dream about a person they liked.

Other

Therapy for recurring nightmares (often associated with posttraumatic stress disorder) can include imagining alternative scenarios that could begin at each step of the dream.[110]

Other associated phenomena

Incorporation of reality

During the night, many external stimuli may bombard the senses, but the brain often interprets the stimulus and makes it a part of a dream to ensure continued sleep.[111] Dream incorporation is a phenomenon whereby an actual sensation, such as environmental sounds, is incorporated into dreams, such as hearing a phone ringing in a dream while it is ringing in reality or dreaming of urination while wetting the bed. The mind can, however, awaken an individual if they are in danger or if trained to respond to certain sounds, such as a baby crying.

The term "dream incorporation" is also used in research examining the degree to which preceding daytime events become elements of dreams. Recent studies suggest that events in the day immediately preceding, and those about a week before, have the most influence.[112] Gary Alan Fine and Laura Fischer Leighton argue that “dreams are external to the individual mind” because “1) dreams are not willed by the individual self; 2) dreams reflect social reality; 3) dreams are public rhetoric; and 4) dreams are collectively interpretable.”[113]

Apparent precognition of real events

According to surveys, it is common for people to feel their dreams are predicting subsequent life events.[114] Psychologists have explained these experiences in terms of memory biases, namely a selective memory for accurate predictions and distorted memory so that dreams are retrospectively fitted onto life experiences.[114] The multi-faceted nature of dreams makes it easy to find connections between dream content and real events.[115] The term "veridical dream" has been used to indicate dreams that reveal or contain truths not yet known to the dreamer, whether future events or secrets.[116]

In one experiment, subjects were asked to write down their dreams in a diary. This prevented the selective memory effect, and the dreams no longer seemed accurate about the future.[117] Another experiment gave subjects a fake diary of a student with apparently precognitive dreams. This diary described events from the person's life, as well as some predictive dreams and some non-predictive dreams. When subjects were asked to recall the dreams they had read, they remembered more of the successful predictions than unsuccessful ones.[118]

Lucid dreaming

Lucid dreaming is the conscious perception of one's state while dreaming. In this state the dreamer may often have some degree of control over their own actions within the dream or even the characters and the environment of the dream. Dream control has been reported to improve with practiced deliberate lucid dreaming, but the ability to control aspects of the dream is not necessary for a dream to qualify as "lucid" — a lucid dream is any dream during which the dreamer knows they are dreaming.[119] The occurrence of lucid dreaming has been scientifically verified.[120]

Oneironaut is a term sometimes used for those who lucidly dream.

Communication through lucid dreaming

In 1975, psychologist Keith Hearne successfully recorded a communication from a dreamer experiencing a lucid dream. On April 12, 1975, after agreeing to move his eyes left and right upon becoming lucid, the subject and Hearne's co-author on the resulting article, Alan Worsley, successfully carried out this task.[121]

Years later, psychophysiologist Stephen LaBerge conducted similar work including:

- Using eye signals to map the subjective sense of time in dreams.

- Comparing the electrical activity of the brain while singing awake and while dreaming.

- Studies comparing in-dream sex, arousal, and orgasm.[122]

Communication between two dreamers has also been documented. The processes involved included EEG monitoring, ocular signaling, incorporation of reality in the form of red light stimuli and a coordinating website. The website tracked when both dreamers were dreaming and sent the stimulus to one of the dreamers where it was incorporated into the dream. This dreamer, upon becoming lucid, signaled with eye movements; this was detected by the website whereupon the stimulus was sent to the second dreamer, invoking incorporation into this dream.[123]

Absent-minded transgression

Dreams of absent-minded transgression (DAMT) are dreams wherein the dreamer absentmindedly performs an action that he or she has been trying to stop (one classic example is of a quitting smoker having dreams of lighting a cigarette). Subjects who have had DAMT have reported waking with intense feelings of guilt. One study found a positive association between having these dreams and successfully stopping the behavior.[124]

Recall

The recollection of dreams is extremely unreliable, though it is a skill that can be trained. Dreams can usually be recalled if a person is awakened while dreaming.[110] Women tend to have more frequent dream recall than men.[110] Dreams that are difficult to recall may be characterized by relatively little affect, and factors such as salience, arousal, and interference play a role in dream recall. Often, a dream may be recalled upon viewing or hearing a random trigger or stimulus. The salience hypothesis proposes that dream content that is salient, that is, novel, intense, or unusual, is more easily remembered. There is considerable evidence that vivid, intense, or unusual dream content is more frequently recalled.[125] A dream journal can be used to assist dream recall, for personal interest or psychotherapy purposes.

For some people, sensations from the previous night's dreams are sometimes spontaneously experienced in falling asleep. However they are usually too slight and fleeting to allow dream recall. At least 95% of all dreams are not remembered. Certain brain chemicals necessary for converting short-term memories into long-term ones are suppressed during REM sleep. Unless a dream is particularly vivid and if one wakes during or immediately after it, the content of the dream is not remembered.[126] Recording or reconstructing dreams may one day assist with dream recall. Using technologies such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electromyography (EMG), researchers have been able to record basic dream imagery,[127] dream speech activity[128] and dream motor behavior (such as walking and hand movements).[129][130]

Individual differences

In line with the salience hypothesis, there is considerable evidence that people who have more vivid, intense or unusual dreams show better recall. There is evidence that continuity of consciousness is related to recall. Specifically, people who have vivid and unusual experiences during the day tend to have more memorable dream content and hence better dream recall. People who score high on measures of personality traits associated with creativity, imagination, and fantasy, such as openness to experience, daydreaming, fantasy proneness, absorption, and hypnotic susceptibility, tend to show more frequent dream recall.[125] There is also evidence for continuity between the bizarre aspects of dreaming and waking experience. That is, people who report more bizarre experiences during the day, such as people high in schizotypy (psychosis proneness) have more frequent dream recall and also report more frequent nightmares.[125]

Déjà vu

One theory of déjà vu attributes the feeling of having previously seen or experienced something to having dreamed about a similar situation or place, and forgetting about it until one seems to be mysteriously reminded of the situation or the place while awake.[131]

Daydreaming

A daydream is a visionary fantasy, especially one of happy, pleasant thoughts, hopes or ambitions, imagined as coming to pass, and experienced while awake.[132] There are many different types of daydreams, and there is no consistent definition amongst psychologists.[132] The general public also uses the term for a broad variety of experiences. Research by Harvard psychologist Deirdre Barrett has found that people who experience vivid dreamlike mental images reserve the word for these, whereas many other people refer to milder imagery, realistic future planning, review of past memories or just "spacing out"—i.e. one's mind going relatively blank—when they talk about "daydreaming."[133][134]'

While daydreaming has long been derided as a lazy, non-productive pastime, it is now commonly acknowledged that daydreaming can be constructive in some contexts.[135] There are numerous examples of people in creative or artistic careers, such as composers, novelists and filmmakers, developing new ideas through daydreaming. Similarly, research scientists, mathematicians and physicists have developed new ideas by daydreaming about their subject areas.

Hallucination

A hallucination, in the broadest sense of the word, is a perception in the absence of a stimulus. In a stricter sense, hallucinations are perceptions in a conscious and awake state, in the absence of external stimuli, and have qualities of real perception, in that they are vivid, substantial, and located in external objective space. The latter definition distinguishes hallucinations from the related phenomena of dreaming, which does not involve wakefulness.

Nightmare

A nightmare is an unpleasant dream that can cause a strong negative emotional response from the mind, typically fear or horror, but also despair, anxiety and great sadness. The dream may contain situations of danger, discomfort, psychological or physical terror. Sufferers usually awaken in a state of distress and may be unable to return to sleep for a prolonged period of time.[136]

Night terror

A night terror, also known as a sleep terror or pavor nocturnus, is a parasomnia disorder that predominantly affects children, causing feelings of terror or dread. Night terrors should not be confused with nightmares, which are bad dreams that cause the feeling of horror or fear.

See also

- Cognitive neuroscience of dreams

- Dream art

- Dream dictionary

- Dream pop

- Dream sequence

- Dream speech

- Dream Yoga

- Dreamcatcher

- Dreamwork

- False awakening

- Hatsuyume

- Incubus

- Lilith, a Sumerian dream demoness

- List of dream diaries

- List of dreams

- Mare (folklore)

- Morpheus

- Mabinogion

- Oneiromancy

- Sleep paralysis

- Spirit spouse

- Succubus

References

- "Dream". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. 2000. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- Kavanau, J.L. (2000). "Sleep, memory maintenance, and mental disorders". Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 12 (2): 199–208. doi:10.1176/jnp.12.2.199. PMID 11001598.

- Hobson, J.A. (2009). "REM sleep and dreaming: towards a theory of protoconsciousness". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10 (11): 803–813. doi:10.1038/nrn2716. PMID 19794431.

- Empson, J. (2002). Sleep and dreaming (3rd ed.)., New York: Palgrave/St. Martin's Press

- Cherry, Kendra. (2015). "10 Facts About Dreams: What Researchers Have Discovered About Dreams Archived 2016-02-21 at the Wayback Machine." About Education: Psychology. About.com.

- Ann, Lee (January 27, 2005). "HowStuffWorks "Dreams: Stages of Sleep"". Science.howstuffworks.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- Eichenlaub, Jean-Baptiste; van Rijn, Elaine; Gaskell, M Gareth; Lewis, Penelope A; Maby, Emmanuel; Malinowski, Josie E; Walker, Matthew P; Boy, Frederic; Blagrove, Mark (2018-06-01). "Incorporation of recent waking-life experiences in dreams correlates with frontal theta activity in REM sleep". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 13 (6): 637–647. doi:10.1093/scan/nsy041. ISSN 1749-5016. PMC 6022568. PMID 29868897.

- Morewedge, Carey K.; Norton, Michael I. (2009). "When dreaming is believing: The (motivated) interpretation of dreams". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 96 (2): 249–264. doi:10.1037/a0013264. PMID 19159131.

- Freud, S. (1900). The Interpretation of Dreams. London: Hogarth Press

- Cheung, Theresa (2006). The Dream Dictionary from A to Z. China: HarperElement. p. 437.

- Lite, Jordan (July 29, 2010). "How Can You Control Your Dreams?". Scientific America. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015.

- Domhoff, W. (2002). The scientific study of dreams. APA Press

- Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park: Tjukurpa – Anangu culture Archived July 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine environment.gov.au, June 23, 2006

- Seligman, K. (1948), Magic, Supernaturalism and Religion. New York: Random House

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 71–72, 89–90. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oppenheim, L.A. (1966). Mantic Dreams in the Ancient Near East in G. E. Von Grunebaum & R. Caillois (Eds.), The Dream and Human Societies (pp. 341–350). London, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Caillois, R. (1966). Logical and Philosophical Problems of the Dream. In G.E. Von Grunebaum & R. Caillos (Eds.), The Dream and Human Societies(pp. 23–52). London, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Nils P. Heessel : Divinatorische Texte I : ... oneiromantische Omina. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2007.

- Lincoln, J.S. (1935). The dream in primitive cultures London: Cressett.

- 1991. languages of dreaming : Anthropological approaches to the study of dreaming In other cultures. In Gackenbach J, Sheikh A, eds, Dream images: A call to mental arms. Amityville, N.Y.: Baywood.

- Bulkeley, Kelly (2008). Dreaming in the world's religions: A comparative history. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-0-8147-9956-7.

- O'Neil, C.W. (1976). Dreams, culture and the individual. San Francisco: Chandler & Sharp.

- Cicero, De Republica, VI, 10

- Herodotus. The Histories. Oxford University Press. p. 414.

- "Rhonabwy". Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- "BBC Wales - History - Themes - the Dream of Macsen Wledig". Archived from the original on 2017-07-20. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- Bar, Shaul (2001). A letter that has not been read: Dreams in the Hebrew Bible. Hebrew Union College Press. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Edgar, Iain (2011). The Dream in Islam: From Qur'anic Tradition to Jihadist Inspiration. Oxford: Berghahn Books. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-85745-235-1. Archived from the original on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2012-03-09.

- Edgar, Iain R.; Henig, David (September 2010). "Istikhara: The Guidance and practice of Islamic dream incubation through ethnographic comparison" (PDF). History and Anthropology. 21 (3): 251–262. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1012.7334. doi:10.1080/02757206.2010.496781. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-11-08.

- Krishnananda, Swami (16 November 1996). "The Mandukya Upanishad, Section 4". Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Young, S. (2003). "Dreams". The encyclopedia of South Asian Folklore. 13. p. 7. Archived from the original on 2018-02-25. Retrieved 2018-02-24 – via Indian Folklife.

- Kher, Chitrarekha V. (1992). Buddhism As Presented by the Brahmanical Systems. Sri Satguru Publications. ISBN 978-81-7030-293-3.

- Tedlock, B (1981). "Quiche Maya dream Interpretation". Ethos. 9 (4): 313–350. doi:10.1525/eth.1981.9.4.02a00050.

- Webb, Craig (1995). "Dreams: Practical Meaning & Applications". The DREAMS Foundation. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- "Native American Dream Beliefs". Dream Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- "The book of the duchess". Washington State University. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- "William Langland's The Vision Concerning Piers Plowman". The History Guide. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- Phillips Lovecraft, Howard (1995). The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft: Dreams of Terror and Death. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-38421-8. Archived from the original on 2013-09-03.

- "The Neverending Story – Book – Pictures – Video -Icons". Neverendingstory.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- Van Riper, A. Bowdoin (2002). Science in popular culture: a reference guide. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-313-31822-1.

- Van Riper, op. cit., p. 57.

- Dement, W.; Kleitman, N. (1957). "The Relation of Eye Movements during Sleep to Dream Activity". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 53 (5): 339–346. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.308.6874. doi:10.1037/h0048189. PMID 13428941.

- Lee Ann Obringer (2006). How Dream Works. Archived from the original on April 18, 2006. Retrieved May 4, 2006.

- "Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 2006. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2007.

- Aston-Jones G., Gonzalez M., & Doran S. (2007). "Role of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in arousal and circadian regulation of the sleep-wake cycle." In G.A. Ordway, M.A. Schwartz, & A. Frazer Brain Norepinephrine: Neurobiology and Therapeutics. Cambridge UP.

- Siegel J.M. (2005). "REM Sleep." Ch. 10 in Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 4th ed. M.H. Kryger, T. Roth, & W.C. Dement, eds. Elsevier. 120–135. Accessed July 21, 2010. Psychology.uiowa.edu Archived November 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Trimble, M.R. (1989). The Prefrontal Cortex: Anatomy, Physiology and Neuropsychology of the Frontal Lobe. British Journal of Psychiatry

- Barbara Bolz. "How Time Passes in Dreams Archived 2016-01-31 at the Wayback Machine" in A Moment of Science. Indiana Public Media. September 2, 2009. Accessed August 8, 2010.

- Takeuchi, Tomoka (June 2005). "Dream mechanisms: Is REM sleep indispensable for dreaming?". Sleep & Biological Rhythms. 3 (2): 56–63. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8425.2005.00165.x.

- Braun, A. (1 July 1997). "Regional cerebral blood flow throughout the sleep-wake cycle. An H2(15)O PET study". Brain. 120 (7): 1173–1197. doi:10.1093/brain/120.7.1173. PMID 9236630.

- Siclari, Francesca; Baird, Benjamin; Perogamvros, Lampros; Bernardi, Giulio; LaRocque, Joshua J; Riedner, Brady; Boly, Melanie; Postle, Bradley R; Tononi, Giulio (10 April 2017). "The neural correlates of dreaming". Nature Neuroscience. 20 (6): 872–878. doi:10.1038/nn.4545. PMC 5462120. PMID 28394322.

- Solms, Mark (2014-02-25). The Neuropsychology of Dreams: A Clinico-anatomical Study (1 ed.). Psychology Press. doi:10.4324/9781315806440. ISBN 9781315806440.

- Wierzynski, Casimir M.; Lubenov, Evgueniy V.; Gu, Ming; Siapas, Athanassios G. (February 2009). "State-Dependent Spike-Timing Relationships between Hippocampal and Prefrontal Circuits during Sleep". Neuron. 61 (4): 587–596. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.011. PMC 2701743. PMID 19249278.

- Lewis, Penelope A.; Knoblich, Günther; Poe, Gina (June 2018). "How Memory Replay in Sleep Boosts Creative Problem-Solving" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 22 (6): 491–503. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2018.03.009. PMID 29776467.

- Solms, Mark (December 2000). "Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 23 (6): 843–850. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00003988.

- Anne Myers; Christine H. Hansen (14 April 2011). Experimental Psychology. Cengage Learning. p. 168. ISBN 0-495-60231-0.

- Stanley Coren (16 July 2012). Do Dogs Dream?: Nearly Everything Your Dog Wants You to Know. W. W. Norton. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-393-08388-0.

- Lesku, J.A.; Meyer, L.C.R.; Fuller, A.; Maloney, S.K.; Dell'Omo, G.; Vyssotski, A.L.; Rattenborg, N.C. (2011). "Ostriches sleep like platypuses". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): 1–7. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623203L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023203. PMC 3160860. PMID 21887239.

- Williams, Daniel (April 5, 2007). "While you were sleeping". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- "Dream". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- "Sleep". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- Williams, Daniel (April 5, 2007). "While you were sleeping". Time magazine. Archived from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- Tsoukalas, I (2012). "The origin of REM sleep: A hypothesis". Dreaming. 22 (4): 253–283. doi:10.1037/a0030790.

- Vitelli, R. (2013). Exploring the Mystery of REM Sleep. Psychology Today, On-line blog, March 25

- Freud, S. (1949)., p. 44

- Nagera, Humberto, ed. (2014) [1969]. "Latent dream-content (pp. 31ff.)". Basic Psychoanalytic Concepts on the Theory of Dreams. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-67048-3.

- Nagera, Humberto, ed. (2014) [1969]. "Manifest content (pp. 54ff.)". Basic Psychoanalytic Concepts on the Theory of Dreams. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-67047-6.

- Freud, S. New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (pp. 38–70).

- Domhoff, G.W. (2000). Moving Dream Theory Beyond Freud and Jung. Paper presented to the symposium "Beyond Freud and Jung?", Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, 9/23/2000.

- "The Folly of Dream Interpretation". Psychology Today. 29 July 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Jung, 1964, p. 21

- Jung, 1969

- Wegner, D.M.; Wenzlaff, R.M.; Kozak, M. (2004). "The Return of Suppressed Thoughts in Dreams". Psychological Science. 15 (4): 232–236. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00657.x. PMID 15043639.

- Solms, M. (2000). Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms (23(6) ed.). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. pp. 793–1121.

- Zhang, Jie (2005). Continual-activation theory of dreaming, Dynamical Psychology. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- Zhang, Jie (2004). Memory process and the function of sleep (PDF) (6–6 ed.). Journal of Theoretics. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 20, 2006. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- Zhang, Jie (2016). Towards a comprehensive model of human memory. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.2103.9606. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- Tarnow, Eugen (2003). How Dreams And Memory May Be Related (5(2) ed.). NEURO-PSYCHOANALYSIS.

- "The Health Benefits of Dreams". Webmd.com. February 25, 2009. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- R. Stickgold, J.A. Hobson, R. Fosse, M. Fosse1 (November 2001). "Sleep, Learning, and Dreams: Off-line Memory Reprocessing". Science. 294 (5544): 1052–1057. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.1052S. doi:10.1126/science.1063530. PMID 11691983.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jessica D. Payne and Lynn Nadel1 (2004). "Sleep, dreams, and memory consolidation: The role of the stress hormone cortisol". Learning & Memory. 11 (6): 671–678. doi:10.1101/lm.77104. ISSN 1072-0502. PMC 534. PMID 15576884.

- Robert, W. Der Traum als Naturnothwendigkeit erklärt. Zweite Auflage, Hamburg: Seippel, 1886.

- Evans, C.; Newman, E. (1964). "Dreaming: An analogy from computers". New Scientist. 419: 577–579.

- Crick, F.; Mitchison, G. (1983). "The function of dream sleep". Nature. 304 (5922): 111–114. Bibcode:1983Natur.304..111C. doi:10.1038/304111a0. PMID 6866101.

- Coutts, R (2008). "Dreams as modifiers and tests of mental schemas: an emotional selection hypothesis". Psychological Reports. 102 (2): 561–574. doi:10.2466/pr0.102.2.561-574. PMID 18567225.

- Revonsuo, A. (2000). "The reinterpretation of dreams: an evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 23 (6): 877–901. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00004015. PMID 11515147.

- Blackmore, Susan (2004). Consciousness an introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-19-515343-9.

- Blackmore, Susan (2004). Consciousness an introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 342–343. ISBN 978-0-19-515343-9.

- Tubo, J. "The evolution of dreaming". Archived from the original on 2011-09-28.

- Franklin, M; Zyphur, M (2005). "The role of dreams in the evolution of the human mind" (PDF). Evolutionary Psychology. 3: 59–78. doi:10.1177/147470490500300106. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-08-11.

- Hobson, J.A. (2005). Thirteen Dreams that Freud Never Had. New York: Pi Press.

- Barrett, Deirdre (2007). "An Evolutionary Theory of Dreams and Problem-Solving". In Barrett, D.L.; McNamara, P. (eds.). The New Science of Dreaming, Volume III: Cultural and Theoretical Perspectives on Dreaming. New York: Praeger/Greenwood. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Barrett, Deirdre (2001). The Committee of Sleep: How Artists, Scientists, and Athletes Use their Dreams for Creative Problem Solving—and How You Can Too. New York: Crown Books/Random House.

- "Barrett, Deirdre. The 'Committee of Sleep': A Study of Dream Incubation for Problem Solving. Dreaming: Journal of the Association for the Study of Dreams, 1993, 3, pp. 115–123". Asdreams.org. Archived from the original on November 18, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Blackmore, Susan (2004). Consciousness an Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 342–343. ISBN 978-0-19-515343-9.

- Cartwright, Rosalind D (1993). "Functions of Dreams". Encyclopedia of Sleep and Dreaming.

- Vedfelt, Ole (1999). The Dimensions of Dreams. Fromm. ISBN 978-0-88064-230-9.

- Ferenczi, S. (1913) To whom does one relate one's dreams? In: Further Contributions to the Theory and Technique of Psycho-Analysis. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 349.

- Kramer, M. (1993) The selective mood regulatory function of dreaming: An update and revision. In: The Function of Dreaming. Ed., A. Moffitt, M. Kramer, & R. Hoffmann. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Hartmann, E. (1995). "Making connections in a safe place: Is dreaming psychotherapy?". Dreaming. 5 (4): 213–228. doi:10.1037/h0094437.

- LaBerge, S. & DeGracia, D.J. (2000). Varieties of lucid dreaming experience. In R.G. Kunzendorf & B. Wallace (Eds.), Individual Differences in Conscious Experience (pp. 269–307). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Hall, C., & Van de Castle, R. (1966). The Content Analysis of Dreams. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. Content Analysis Explained Archived 2007-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "How do blind people dream? – The Body Odd". March 2012. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- Zadra, A., "1093: Sex dreams: what to men and women dream about?" Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Sleep Volume 30, Abstract Supplement, 2007 A376.

- "Badan Pusat Statistik "Indonesia Young Adult Reproductive Health Survey 2002–2004" p. 27" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Michael Schredl; Petra Ciric; Simon Götz; Lutz Wittmann (November 2004). "Typical Dreams: Stability and Gender Differences". The Journal of Psychology. 138 (6): 485–94. doi:10.3200/JRLP.138.6.485-494. PMID 15612605.

- Alleyne, Richard (October 17, 2008). "Black and white TV generation have monochrome dreams". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on October 12, 2009.

- Harrison, John E. (2001). Synaesthesia: The Strangest Thing. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-263245-6.

- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2009. Vol 96, No 2, 249–264

- "The Science Behind Dreams and Nightmares". Npr.org. Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Antrobus, John (1993). "Characteristics of Dreams". Encyclopedia of Sleep and Dreaming.

- Geneviève Alain, MPs; Tore A. Nielsen, PhD; Russell Powell, PhD; Don Kuiken, PhD (July 2003). "Replication of the Day-residue and Dream-lag Effect". 20th Annual International Conference of the Association for the Study of Dreams. Archived from the original on 2003-04-16.

- Fine, Gary Alan; Leighton, Laura Fischer (1993-01-01). "Nocturnal Omissions: Steps Toward a Sociology of Dreams". Symbolic Interaction. 16 (2): 95–104. doi:10.1525/si.1993.16.2.95. JSTOR 10.1525/si.1993.16.2.95.

- Hines, Terence (2003). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 78–81. ISBN 978-1-57392-979-0.

- Gilovich, Thomas (1991). How We Know What Isn't So: the fallibility of human reason in everyday life. Simon & Schuster. pp. 177–180. ISBN 978-0-02-911706-4.

- "Llewellyn Worldwide – Encyclopedia: Term: Veridical Dream". www.llewellyn.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-18. Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- Alcock, James E. (1981). Parapsychology: Science or Magic?: a psychological perspective. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-025773-0. via Hines, Terence (2003). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 78–81. ISBN 978-1-57392-979-0.

- Madey, Scott; Thomas Gilovich (1993). "Effects of Temporal Focus on the Recall of Expectancy-Consistent and Expectancy-Inconsistent Information". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 65 (3): 458–468. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.3.458. PMID 8410650. via Kida, Thomas (2006). Don't Believe Everything You Think: The 6 Basic Mistakes We Make in Thinking. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-408-8.

- Lucid dreaming FAQ Archived 2007-03-13 at the Wayback Machine by The Lucidity Institute at Psych Web.

- Watanabe, T. (2003). "Lucid Dreaming: Its Experimental Proof and Psychological Conditions". J Int Soc Life Inf Sci. 21 (1). ISSN 1341-9226.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2013-10-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), Lucid Dream Communication

- LaBerge, S. (2014). Lucid dreaming: Paradoxes of dreaming consciousness. In E. Cardeña, S. Lynn, S. Krippner (Eds.), Varieties of anomalous experience: Examining the scientific evidence (2nd ed.) (pp. 145–173). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/14258-006

- Olson, Parmy. "Saying 'Hi' Through A Dream: How The Internet Could Make Sleeping More Social". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- Hajek P, Belcher M (1991). "Dream of absent-minded transgression: an empirical study of a cognitive withdrawal symptom". J Abnorm Psychol. 100 (4): 487–91. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.487. PMID 1757662.

- Watson, David (2003). "To dream, perchance to remember: Individual differences in dream recall". Personality and Individual Differences. 34 (7): 1271–1286. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00114-9.

- Hobson, J.A.; McCarly, R.W. (1977). "The brain as a dream-state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process". American Journal of Psychiatry. 134 (12): 1335–1348. doi:10.1176/ajp.134.12.1335. PMID 21570.

- Morelle, Rebecca (2013-04-04). "Scientists 'read dreams' using brain scans – BBC News". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- Mcguigan, F. (2012-12-02). The Psychophysiology of Thinking: Studies of Covert Processes. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-14700-2.

- Cvetkovic, Dean; Cosic, Irena (2011-06-22). States of Consciousness: Experimental Insights into Meditation, Waking, Sleep and Dreams. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-18047-7.

- Oldis, Daniel (2016-02-04). "Can We Turn Our Dreams Into Watchable Movies?". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- Lohff, David C. (2004). The Dream Directory: The Comprehensive Guide to Analysis and Interpretation. Running Press. ISBN 978-0-7624-1962-3.

- Klinger, Eric (October 1987). Psychology Today.

- Barrett, D.L. (1979). "The Hypnotic Dream: Its Content in Comparison to Nocturnal Dreams and Waking Fantasy". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 88 (5): 584–591. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.88.5.584.

- Barrett, D.L. "Fantasizers and Dissociaters: Two types of High Hypnotizables, Two Imagery Styles". in R. Kusendorf, N. Spanos, & B. Wallace (Eds.) Hypnosis and Imagination. New York: Baywood, 1996. and, Barrett, D.L. "Dissociaters, Fantasizers, and their Relation to Hypnotizability" in Barrett, D.L. (Ed.) Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy, (2 vol.): Vol. 1: History, theory and general research, Vol. 2: Psychotherapy research and applications, New York: Praeger/Greenwood, 2010.

- Tierney, John (June 28, 2010). "Discovering the Virtues of a Wandering Mind". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2017.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, TR, p. 631

Further reading

- Dreaming (journal)

- Jung, Carl (1934). The Practice of Psychotherapy. "The Practical Use of Dream-analysis". New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 139–. ISBN 978-0-7100-1645-4.

- Jung, Carl (2002). Dreams (Routledge Classics). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26740-3.

- Harris, William V., Dreams and Еxperience in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press, 2009).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dreaming. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dream |

- Dreams on In Our Time at the BBC

- LSDBase – an online sleep research database documenting the physiological effects of dreams through biofeedback.

- Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism website

- The International Association for the Study of Dreams

- Dream at Curlie

- Dixit, Jay (November 2007). "Dreams: Night School". Psychology Today. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- alt.dreams A long-running USENET forum wherein readers post and analyze dreams.